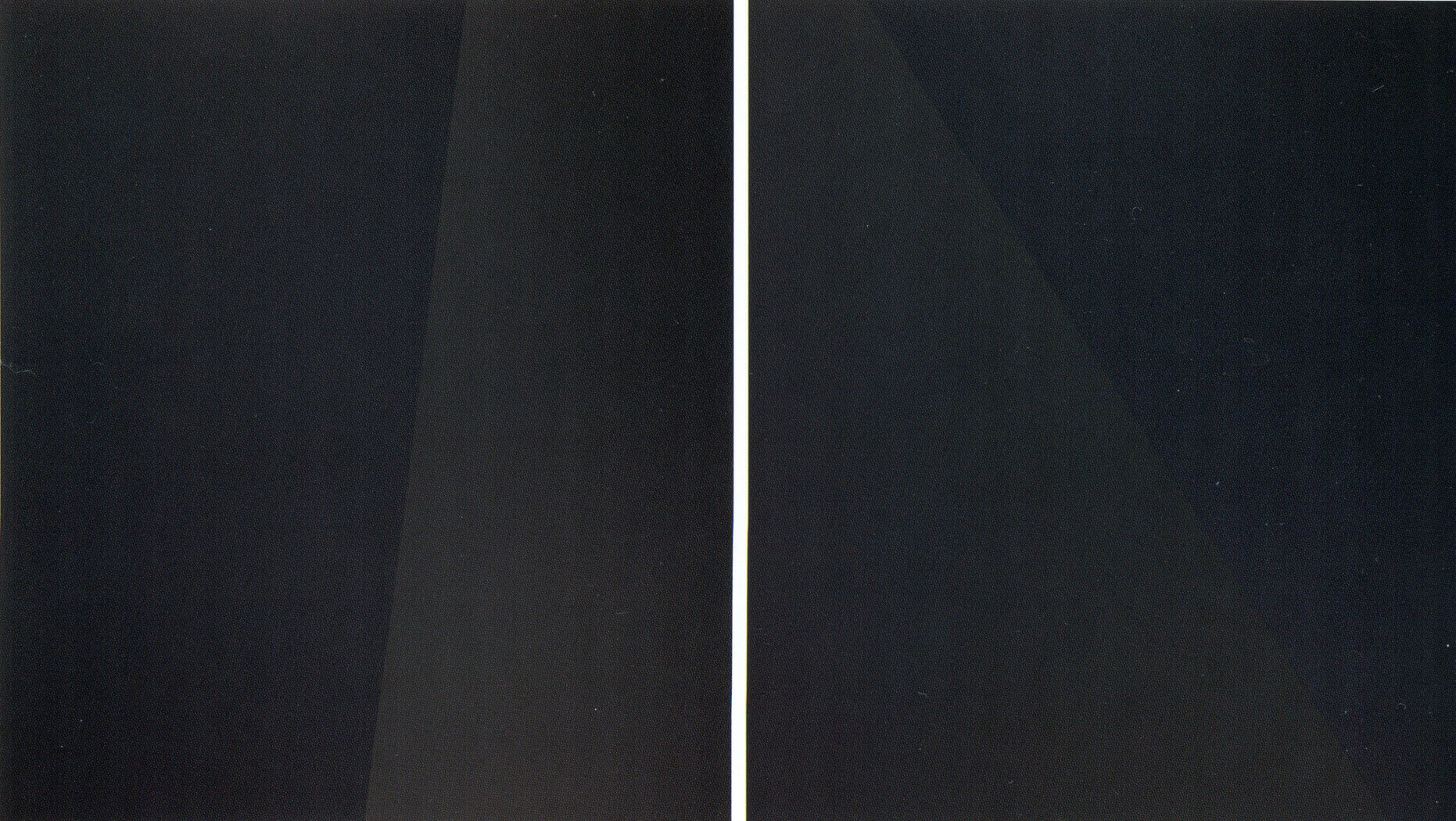

Jericho 1 1978

Yves Gaucher, Jericho 1: An Allusion to Barnett Newman (Une allusion à Barnett Newman), 1978

Diptych, acrylic on canvas, each element: 320 x 280 cm

© Estate of Yves Gaucher / SODRAC (2015)

In the late 1970s Gaucher brought the diagonal back into compositional play, and did so on a grand scale in a series of single or diptych paintings titled Jericho 1, 2, or 3, all subtitled An Allusion to Barnett Newman. Barnett Newman (1905–1970) had played an important role for Gaucher as well as for Guido Molinari (1933–2004) and Claude Tousignant (b. 1932), confirming for them the validity of their own respective experiments during the early 1960s with large-scale and simple fields of colour.

For his Jericho series Gaucher was influenced by Newman’s Jericho, 1968–69, a painting in which Newman aimed to “break the format,” taking on the challenge of the triangle “without getting trapped by its shape or by the perspective,” according to the critic Thomas Hess. Newman’s problem was in effect not dissimilar to the one Gaucher had posed for himself in paintings like Two Blues, Two Greys, 1976: to take on the challenge of horizontal bands of colour without letting the horizon line trap him into landscape painting. With Jericho 1 the diagonal resurfaces, not at the edges but as a structural component within the fields of the paintings.

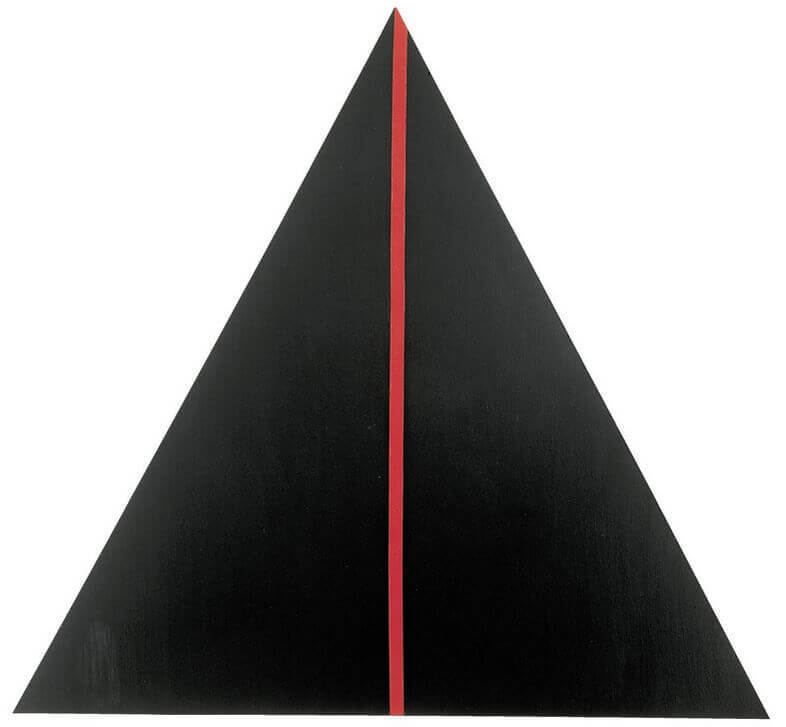

The Jericho paintings are structured on the theme of a vertically divided triangle, cut down the middle, creating in Jericho 1 and 2 a diptych format. In both paintings the two canvases are separated just enough to establish the necessary dramatic tension that challenges the viewer’s need to complete the triangle, not only across the two parts of the diptychs but also in its upward thrust beyond the canvases’ top edges. Add to this the need to reconcile the equally powerful overall lateral tensions between and across the entire work’s two internally and diagonally bisected rectangles. The sheer expanse of these two Jerichos, their minimal means, and their almost environmental scale can be measured only with the body’s full kinesthetic response. Their colours are dark and contemplative.

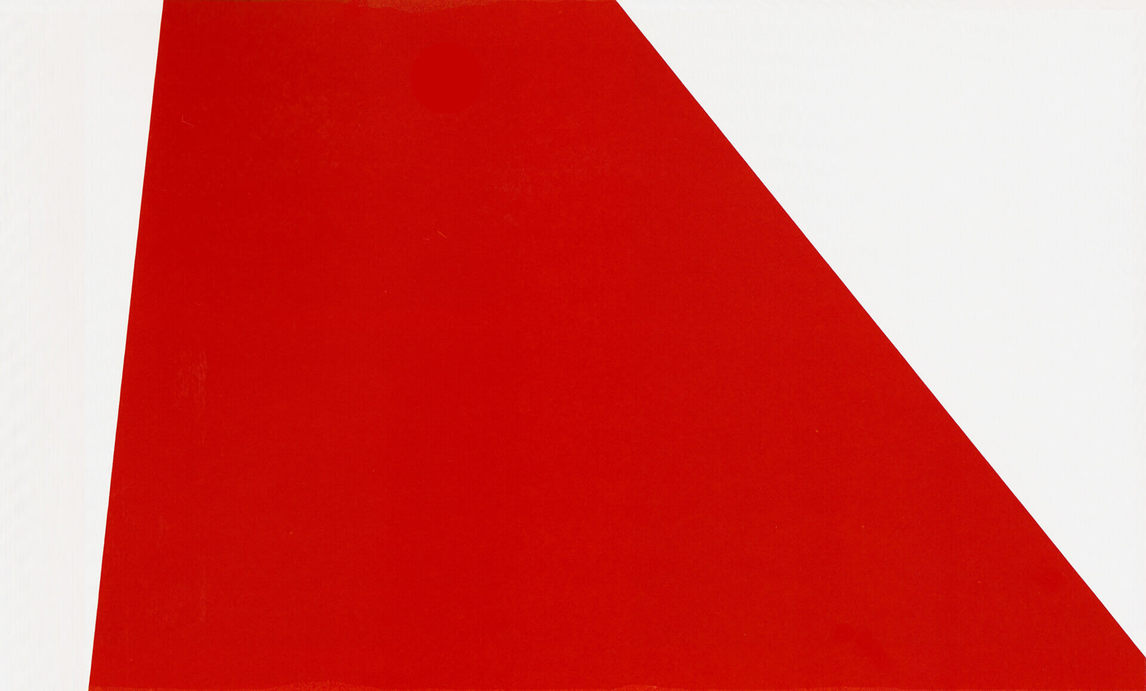

Er-Rcha, the last painting of the Jericho series (its title is the Arabic name for Jericho), is proof of Gaucher’s sureness of measure in both colour and structure. It is composed of a red irregular triangle, truncated above and on the right, constrained by the white planes that fill out the balance of the rectangular canvas. So extreme are the tensions on the edges of the canvas where the red and white planes meet, and the tension between those three planes, that the painting holds its rectangular shape only with the greatest difficulty.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements