Yves Gaucher (1934–2000) was one of Canada’s foremost abstract painters of the second half of the twentieth century. He first made his mark as an innovative printmaker, winning international prizes for his work. After turning to painting in 1964 and for the rest of his life, he pursued his abstract style with relentless self-criticism and uncommon purity.

Early Years

Yves Gaucher was born in Montreal on January 3, 1934, the sixth of eight children. His father owned a pharmacy and also practised as an optometrist and optician. The business was sufficiently successful that Gaucher and his siblings attended the best Montreal schools. During the last years of his father’s life the family lived in Westmount, an affluent residential area in the city.

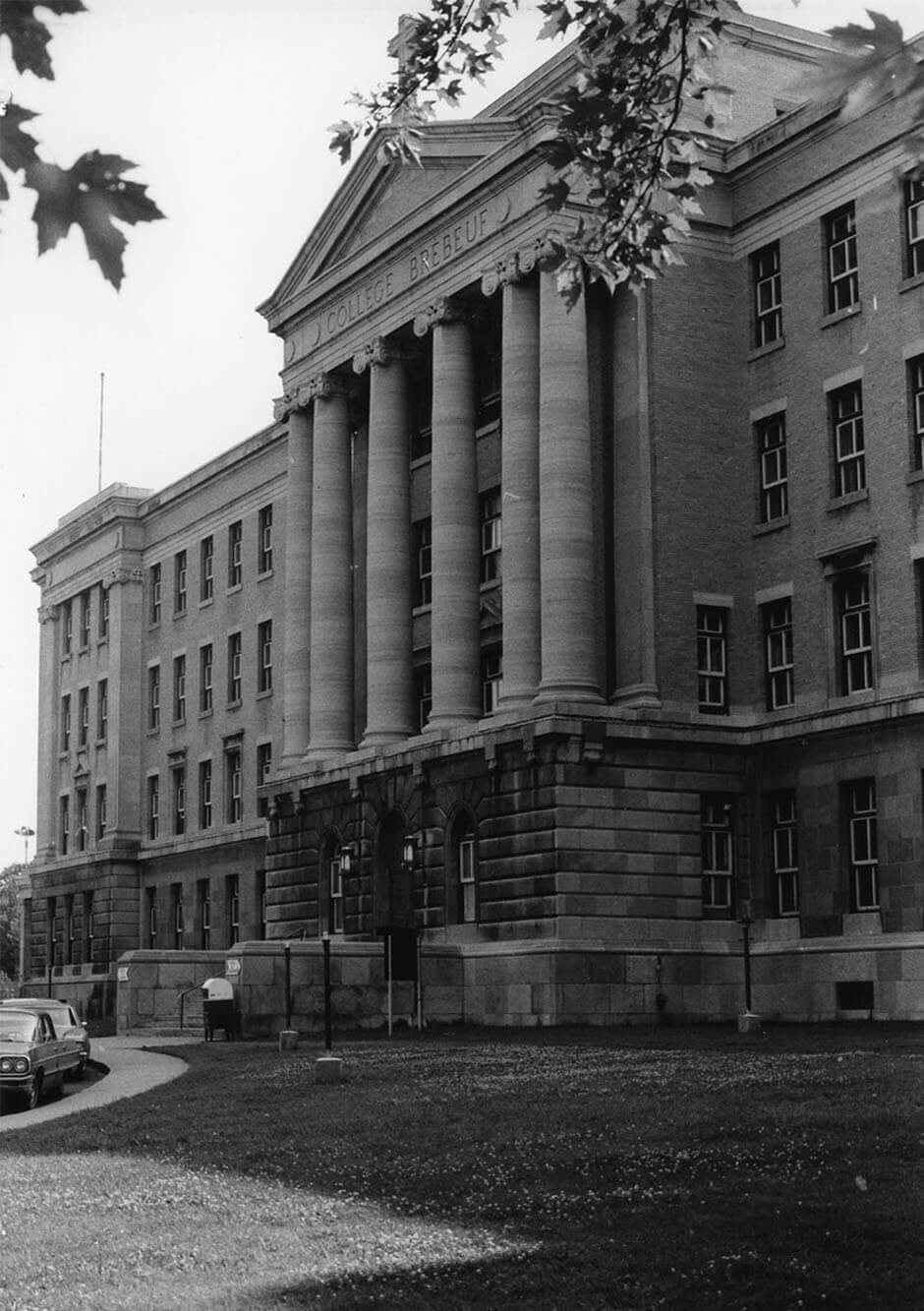

Gaucher’s school years were spent in the Catholic system. After grade school he attended the Jesuit-founded Collège Sainte-Marie and subsequently the Collège Jean-de-Brébeuf. By his own account he was an undisciplined student, but he developed a predilection for Greek and Latin literature, and drawing was his favourite diversion during study periods. Combining his two interests, however, proved fatal: he was expelled from Collège Brébeuf when he was caught copying an “indecent” image from ancient art (presumably a nude) from his illustrated Larousse dictionary. The school already had their eye on him as a potential troublemaker because his older brother had been expelled a few years earlier when a novel by Colette, one of the many authors banned by the clergy, was found in his briefcase.

Gaucher had been very religious and even entertained the notion of becoming a priest. But the injustice of his expulsion turned him away from the church and eventually away from any organized system of belief. A year after his expulsion he switched to an English-language Protestant school, enrolling at Sir George Williams College, which later became a university but in 1952 was still functioning as a high school. It was there that he took his first art course. He never earned a degree.

A Time of Indecision

Music had always been important to Gaucher. He was raised in a musical home, where everyone played an instrument. Gaucher’s mother gave him one piano lesson, an event he remembers vividly as one of the central experiences of his childhood. He began to play trumpet at age twelve at the Collège Sainte-Marie and practised enthusiastically, becoming a solo trumpeter in the college orchestra.

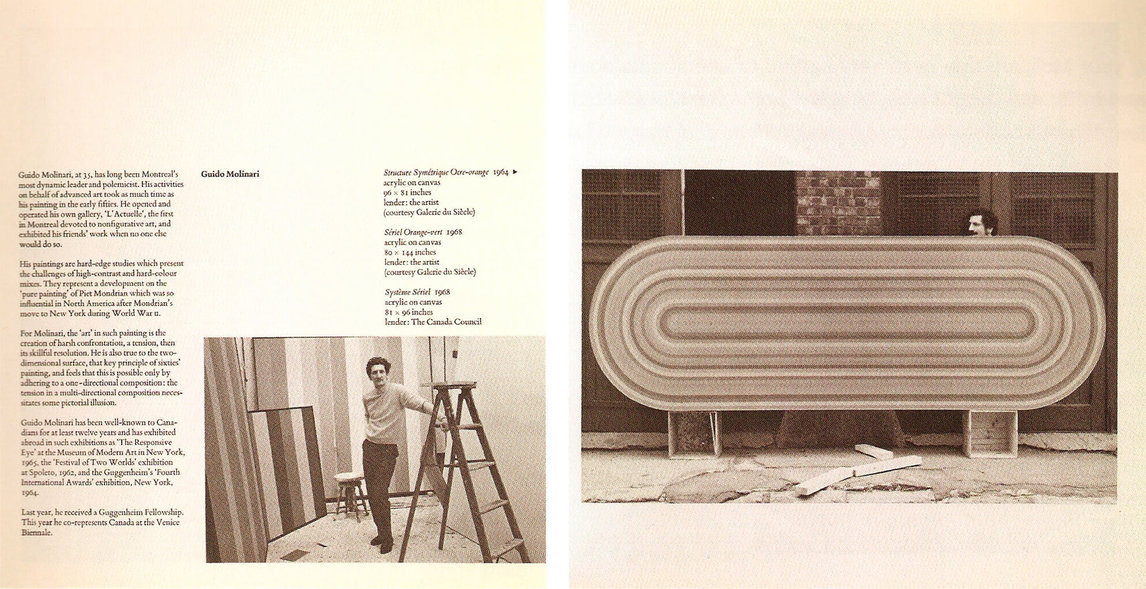

His first full-time job was with the CBC, where he started in the mailroom. But his real ambition was to become a radio announcer, and, in anticipation of having his own jazz program, he took courses to improve his English pronunciation. In the meantime he played gigs at night, even organizing a few jam sessions in 1955–56 at Galerie L’Actuelle, founded by Guido Molinari (1933–2004). By his own admission, however, he failed to grow technically as a musician.

Gaucher playing the vibraphone, c. 1951–52.

From the CBC he went to work for the Canadian Pacific Steamship Company (or the Cunard Line—accounts differ), drawing cargo plans in Montreal during the summer and in Halifax for two winters, when the Montreal harbour was closed. He joined Imperial Oil in Montreal in 1951, starting again as mail boy, but making his first steps upward.

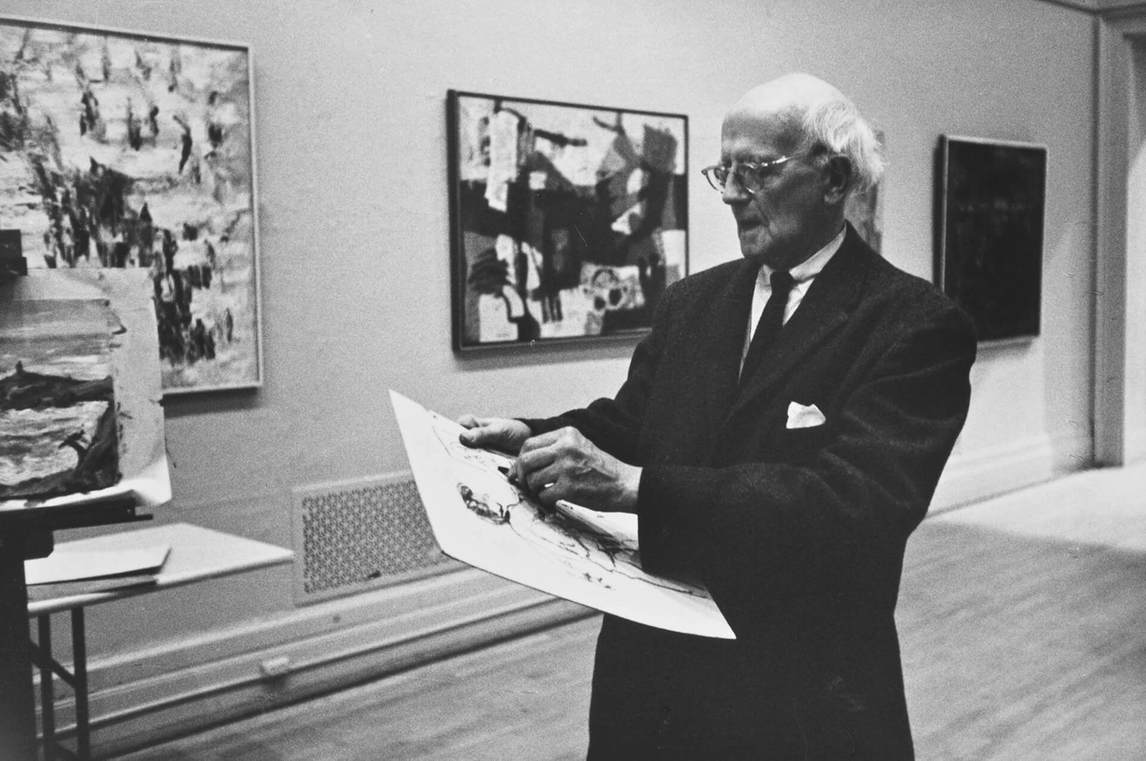

During these years Gaucher continued to draw and paint in watercolours. In Halifax, where he discovered the work of Georges Braque (1882–1963) in a library book, he began to work more elaborately, intrigued by the French artist’s distortions. In 1951, with a sheaf of drawings under his arm, Gaucher made a crucial visit to Arthur Lismer (1885–1969) at the School of Art and Design at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, which precipitated his decision to become an artist. Lismer was a founding member of the Group of Seven and a prominent teacher, and he was tough, Gaucher recalls, “but he put serious questions in my head for the first time. Did I want to be complimented or reassured, or what? He asked if I was ready to make sacrifices, in which case I ought to leave my job and take courses at the museum.”

In 1954 Gaucher resigned from Imperial Oil and enrolled in the museum school. But he stayed only one week: he discovered that for less money he could attend the École des beaux-arts de Montréal, and he switched schools. At the École his first teacher was Suzanne Rivard Le Moyne (1928–2012). Gaucher refused to take courses that did not interest him. He knew what he wanted from the school, did not want to waste time, and felt competent to pick and choose his own program. After a year and a half he was expelled for insubordination, but a change in administration shortly afterward allowed him to return on his own terms, and he continued to attend until 1960.

Suzanne Rivard Le Moyne painting in Paris, 1959.

The Printmaker

Gaucher had enrolled at the École des beaux-arts de Montréal with the intention of becoming a painter. But Automatiste spontaneity—the prevailing avant-garde model in Montreal in the mid-1950s—made him uneasy, the way a painting could change “with one brush stroke.” It was not his “way of behaviour.” Nor was he yet ready for the geometric developments in abstraction on view at places like Galerie L’Actuelle, established by Guido Molinari (1933–2004). As he recalled, “I wasn’t impressed with the kind of work I saw there … Mondrian-inspired art,” presumably referring to the work of Fernand Toupin (1930–2009) and other early Plasticiens.

His own work, however, was beginning to get attention. Writing in 1960, the critic Françoise de Repentigny presciently singled out one of his abstract paintings, Conclusion 230, 1959–60, in a group exhibition at the École, describing it as “transcendental,” a work of “spiritual expression.” One of the factors that had persuaded him to return to the École des beaux-arts was a course in graphics run by Albert Dumouchel (1916–1971). Gaucher was accepted into it on the basis of some line engravings of severely refined landscape motifs that he had exhibited in 1957 in his first solo show, at the Galerie L’Échange.

In 1958 and early 1959, having bought a handbook of techniques, Gaucher began to experiment with Old Master etching techniques but quickly found etching too limiting. He bought a press and set it up in a studio he had created on the second floor of his parents’ two-car garage in Westmount. In 1960 he became the founding president of the Association des peintres-graveurs de Montréal, and devoted the years 1960–64 exclusively to printmaking.

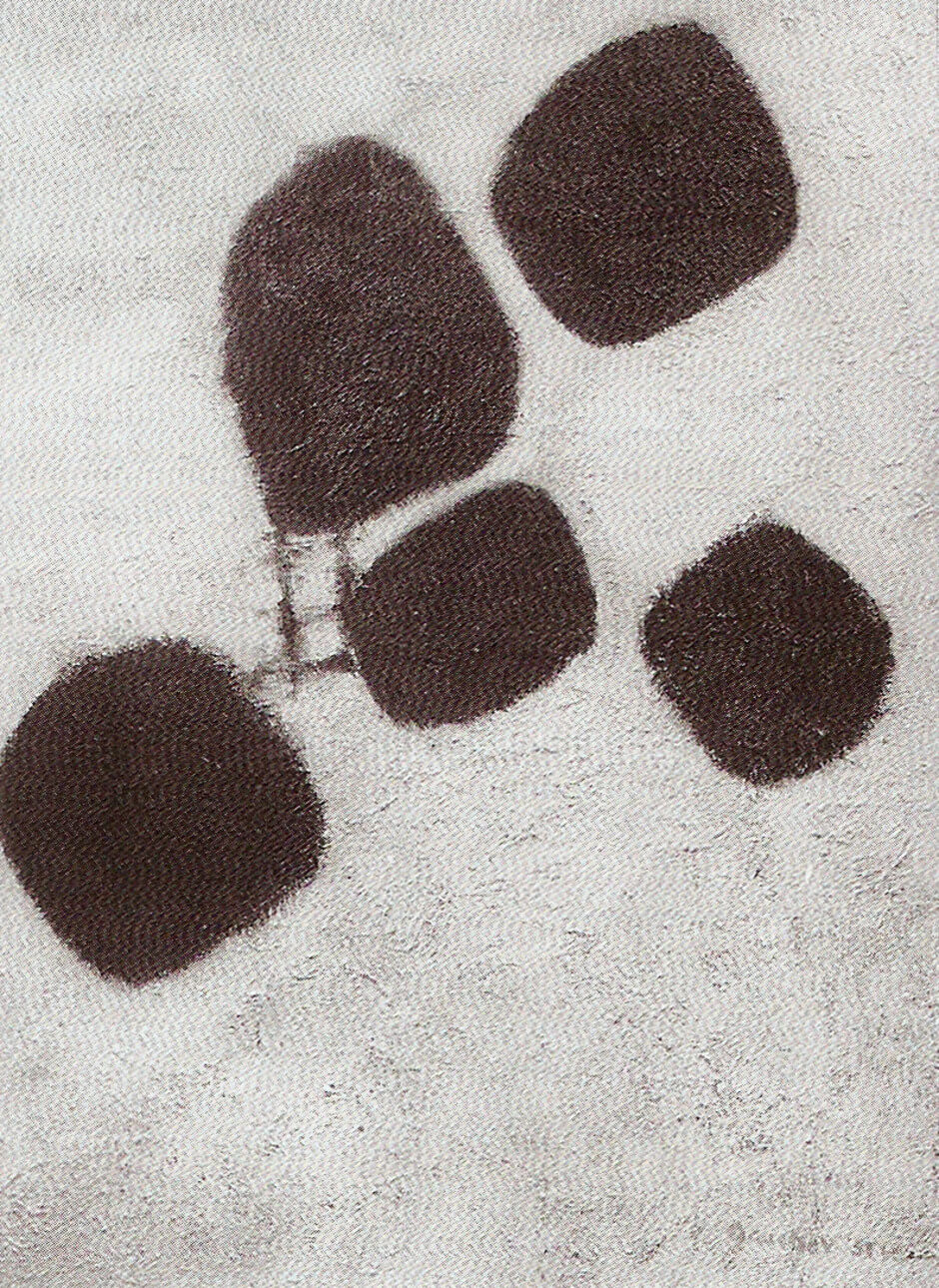

Printmaking, in contrast to painting, could be broken down into staged processes that gave him lots of time to reflect. Step by step he set out to free himself from traditional printing practices with vigorous experimentation and innovation, working especially with unprecedented heavy embossing techniques. He quickly won national and international attention—as well as prizes at major print shows from across Canada to Ljubljana, Yugoslavia, and Grenchen, Switzerland—and had solo shows at Galerie Godard-Lefort in Montreal and the Martha Jackson Gallery in New York. From the latter, the Museum of Modern Art in New York purchased In Homage to Webern No. 2, 1963.

New York and Paris

In 1959 Gaucher began taking regular trips to New York both to satisfy his appetite for jazz and to visit museums and art galleries. He closely followed current developments, including the various reactions to Abstract Expressionism, Pop art, and Op art, and read Art News magazine and It Is: A Magazine for Abstract Art. During this period he also developed a passion for Indian music, along with Eastern philosophy, which would have a profound influence on his art.

His first visit to Paris, in the fall of 1962, offered a number of life-changing experiences. He attended a concert that featured the music of Pierre Boulez, Edgard Varèse, and Anton Webern. Webern’s atonal music disturbed him, because it threw into doubt all his preconceptions about art. In his suite of three prints from 1963 titled In Homage to Webern, Gaucher strove to find visual equivalents for the new music.

In Paris he visited the exhibition of Mark Rothko (1903–1970) that he had already seen the previous year at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the large paintings of the American Abstract Expressionist becoming a model for how he wanted his future painting to enrapture its viewers into a state of sustained trance. As well, seeing the work of Rothko and other American artists like Jasper Johns (b. 1930) and Morris Louis (1912–1962) in the context of Paris made it clear to him that his artistic sensibility had more affinities with contemporary New York painters than with European art.

In 1962, on the strength of a grant from the Canada Council for the Arts, Gaucher rented a larger studio in the Montreal neighbourhood of Saint-Henri. By 1963 he was supporting himself with monthly stipends from the three galleries that showed his work, in Montreal, Toronto, and New York. The same year, he met Germaine Chaussé; they married in October 1964. The couple rented a rambling flat in Old Montreal, where Gaucher set up a press in one room and a painting studio in another.

By 1965 he was sharing a building on Saint-Paul Street East with fellow Montreal artist Charles Gagnon (1934–2003), where Jean McEwen (1923–1999) joined them the following year. The larger studio space allowed for bigger paintings. In 1975 Gaucher moved into a former church on De Bullion Street. Although Gaucher and his fellow Plasticiens came into full maturity during the years of Quebec’s Quiet Revolution, they were not actively political. Paul-Émile Borduas (1905–1960) and the Automatistes had already fought the hard battles for artistic freedom in Quebec and had cleared the way for the more purely aesthetic pursuits of the generation that followed.

The Painter

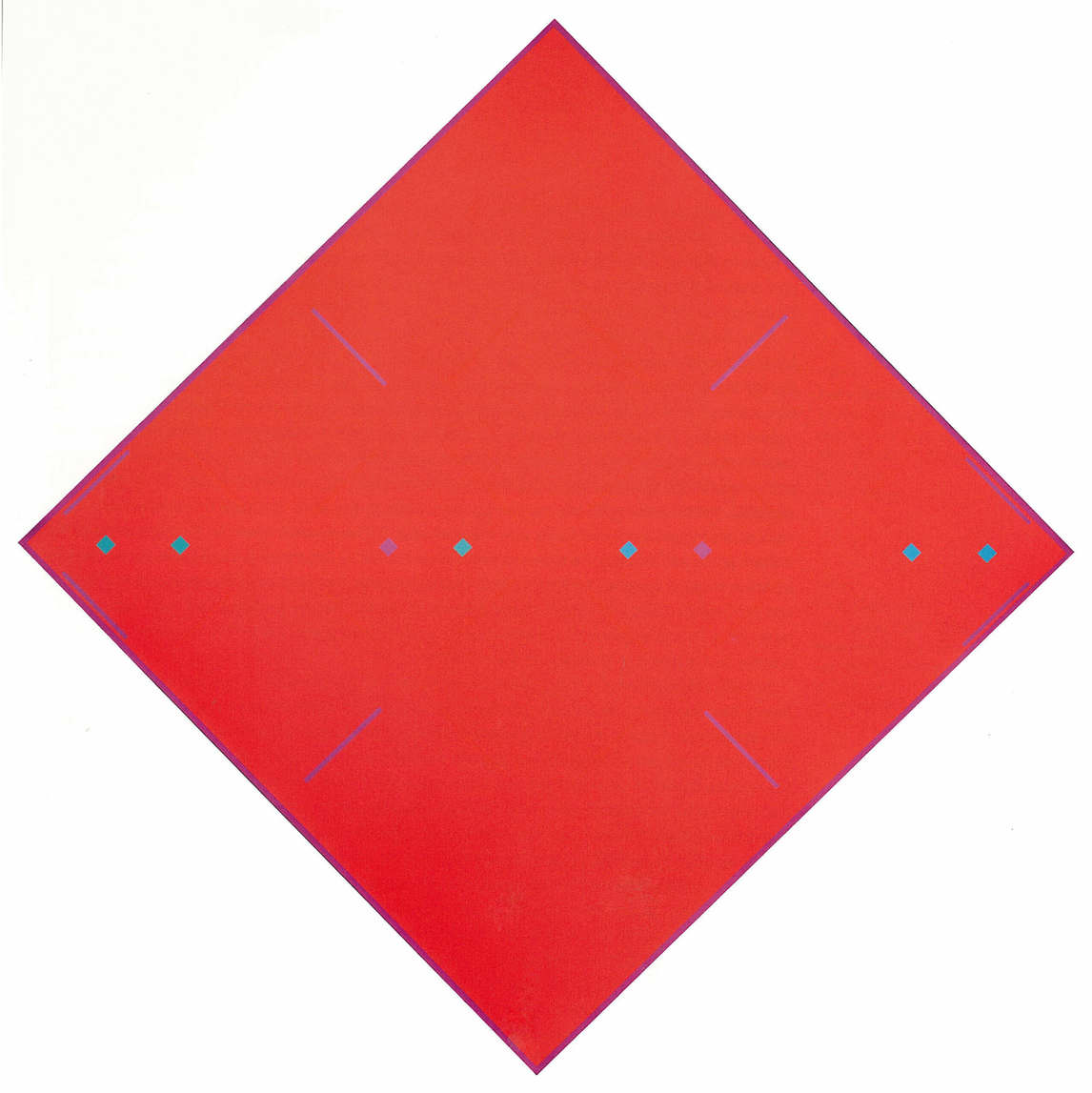

In 1965, with his Square Dances series of paintings, Gaucher entered fully formed into the world of hard-edge chromatic abstraction that, along with the Stripe Paintings of Guido Molinari (1933–2004) and the targets of Claude Tousignant (b. 1932), became the signature style for Montreal in the 1960s.

During that year he participated in a spate of exhibitions throughout the United States devoted to optical art, including The Deceived Eye at the Fort Worth Art Center, Texas; 1 + 1 = 3: An Exhibition of Retinal and Perceptual Art at the University of Texas in Austin and Houston; and Op from Montreal at the University of Vermont in Burlington. In 1966 Gaucher, along with Sorel Etrog (1933–2014) and Alex Colville (1920–2013), represented Canada at the 33rd Venice Biennale, and he had his second solo exhibition at the Martha Jackson Gallery in New York.

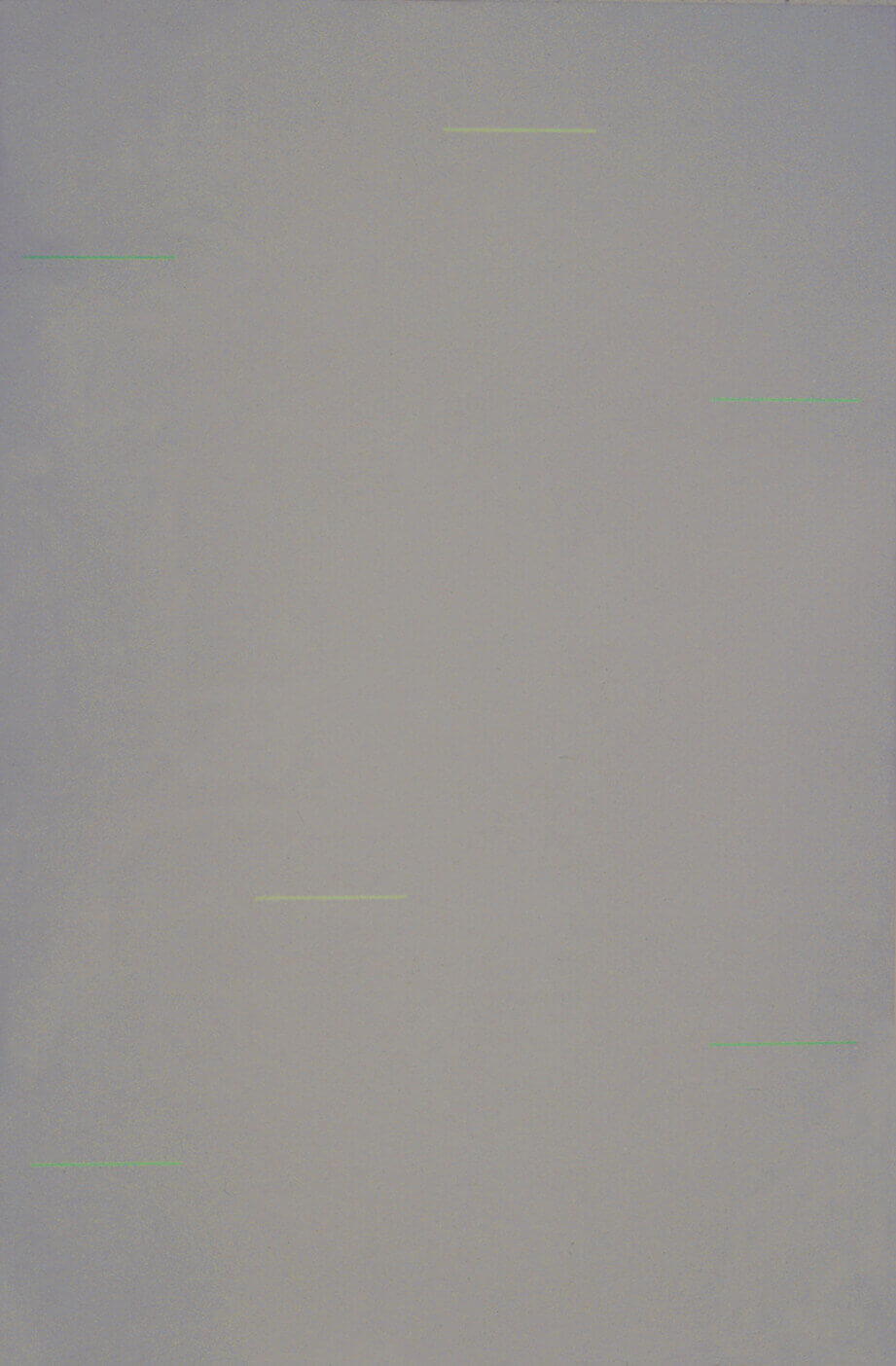

Gaucher’s culminating work of the 1960s was a series of some sixty Grey on Grey paintings that he executed between 1967 and 1969. Three of these, including Alap, 1967, were shown in the 1968 exhibition Canada 101 in Edinburgh, where they strongly impressed the British critic and curator Bryan Robertson, who described Gaucher as a “dazzling artist,” who had made “what are possibly the most beautiful and original—and awe-inspiring—paintings I’ve seen anywhere since the advent of Pollock and Rothko.” An exhibition of twenty-two of the Grey on Greys (along with his In Homage to Webern and Transitions series) was curated by Doris Shadbolt for the Vancouver Art Gallery in 1969 and travelled to Edmonton and the Whitechapel Gallery, London, England.

Gaucher stopped the Grey on Grey series at the end of 1969, concluding that he had effectively explored all the possibilities originally opened up by the Webern prints six years earlier. He then entered a period of doubt about how to proceed. To clear his head—and in response to an invitation to participate in the exhibition Grands formats, at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal in 1970—he executed a large (2.7 x 4.6 m) red painting with techniques and stylistic traits that in innumerable ways ran against the grain of hard-edge painting as he had already defined it, if not against the very core of his being.

Gaucher’s painting crisis may have been existentially grave, but he enjoyed the opportunity to make an outrageous painting. Footage of Gaucher making this red painting became the impetus for Charles Gagnon’s film R69 (begun in 1969 but left unfinished at his death), which also includes a mock interview that reveals an essential mischievous side of Gaucher’s personality.

By 1971, however, Gaucher had regained his stride and over the next three decades produced one astonishing series of paintings after another, never losing his creative momentum. Throughout this time he also continued to draw and make prints.

Continual Success

Even as art world fashions changed during the late 1960s and the 1970s, and painting was dismissed as an outmoded practice from a number of directions—Minimalism, Conceptual art, postmodernist theory—Gaucher continued to sustain an active professional career, getting more regular exposure in Toronto than in Montreal, through commercial galleries such as Gallery Moos, Marlborough Godard Gallery (later Mira Godard Gallery), and Olga Korper Gallery. The New York Cultural Center staged a retrospective exhibition in 1975.

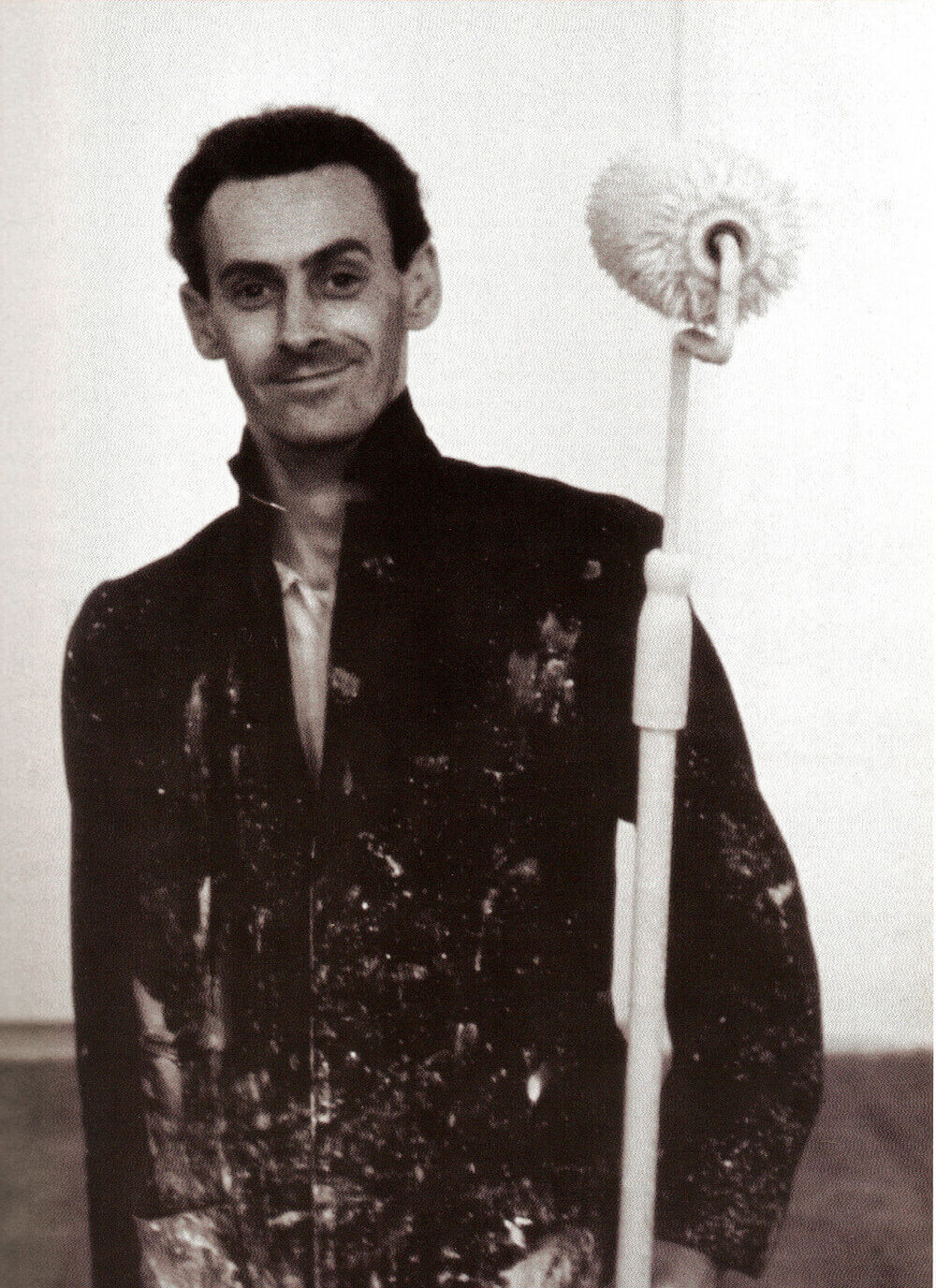

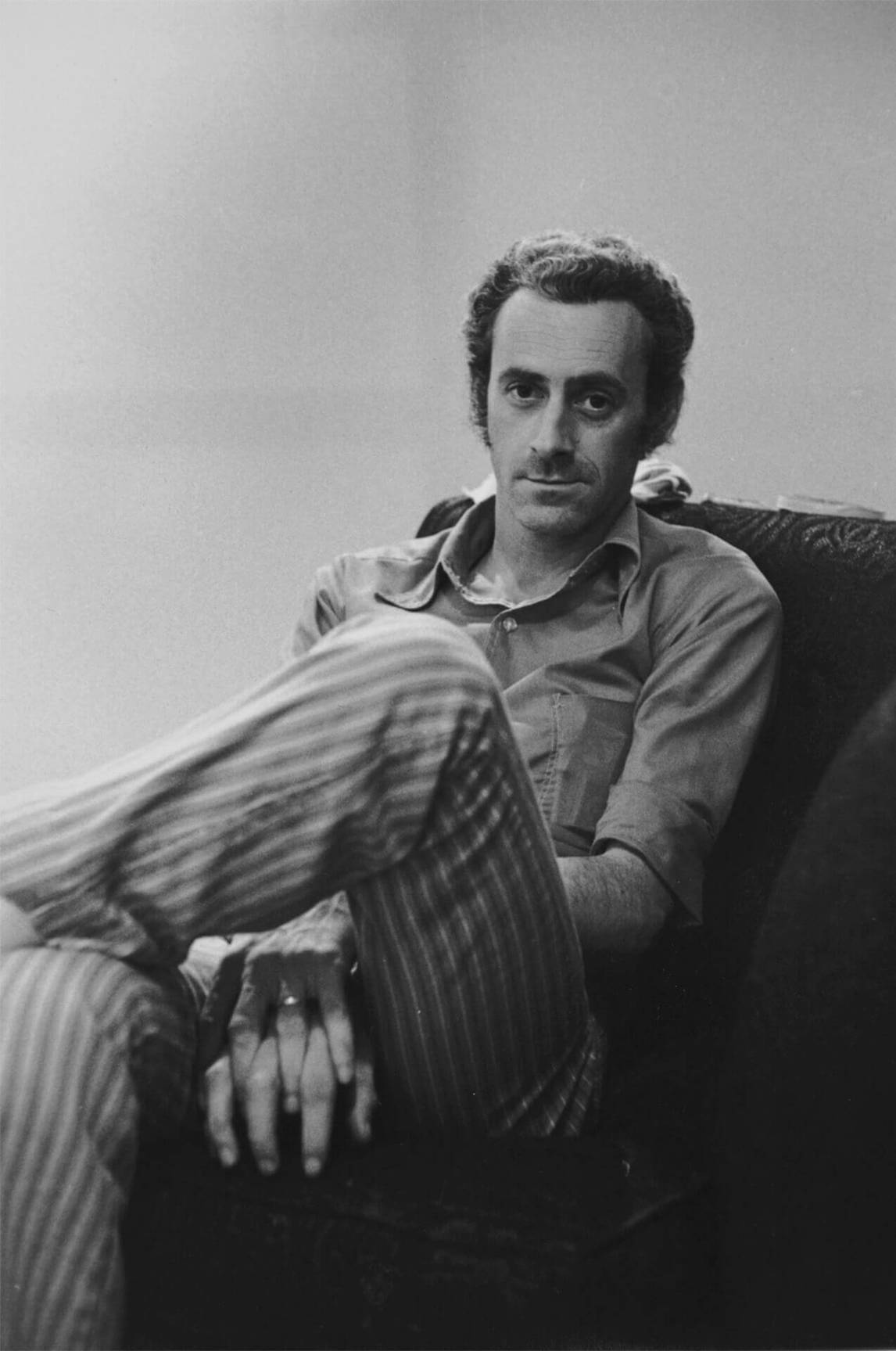

Gaucher in 1971, photographed by Gabor Szilasi.

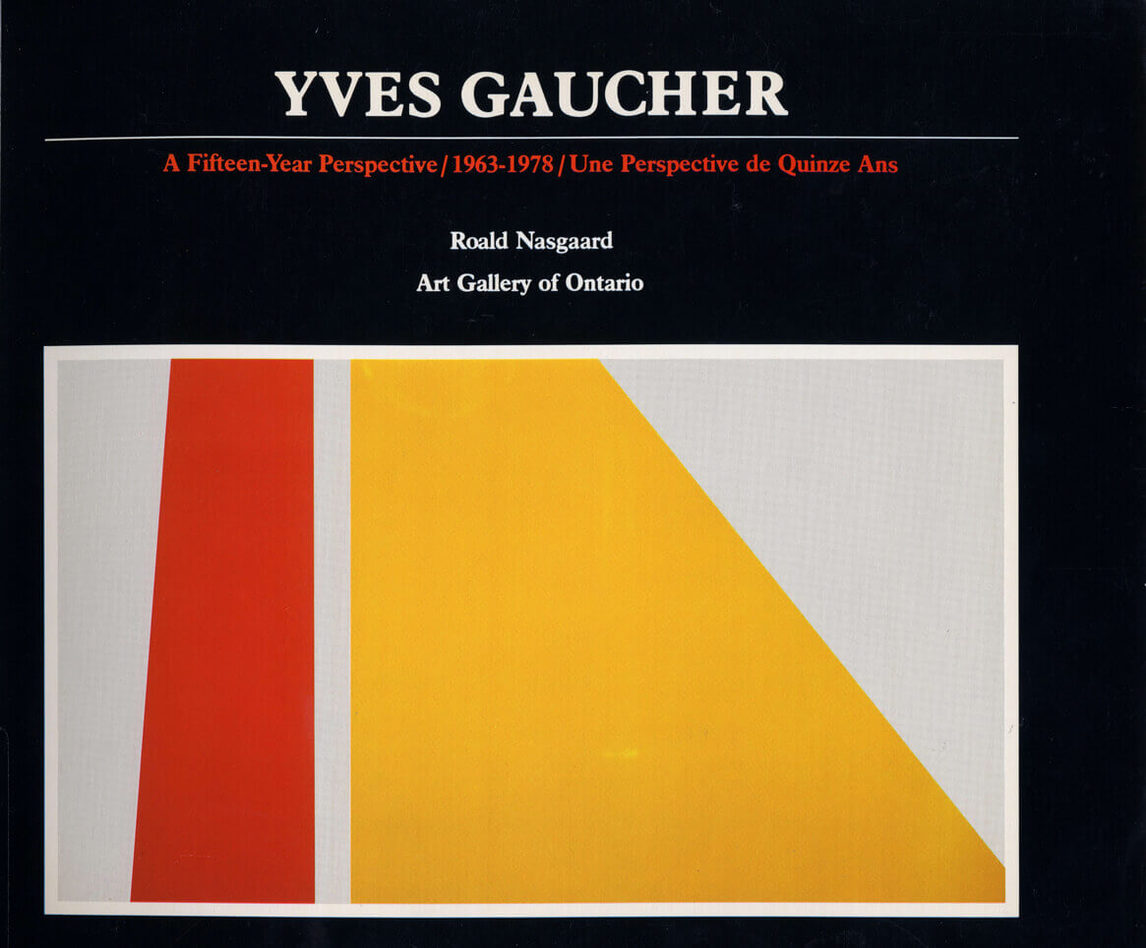

In 1976, in Yves Gaucher, Paintings and Etchings: Perspective 1963–76 at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal, he showed a large selection of Grey on Grey paintings, which had been little seen in Montreal. The Art Gallery of Ontario’s 1979 exhibition Yves Gaucher: A Fifteen-Year Perspective, 1963–1978 followed his painting career through to the end of his Jericho series. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s Gaucher had regular exhibitions at public galleries that included the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal; the Canadian Cultural Centres in Paris, Brussels, and London; 49th Parallel in New York; The Power Plant in Toronto; and the Musée du Québec (now the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec).

In the meantime he and his wife, Germaine, purchased and renovated a house in Notre-Dame-de-Grâce, a residential neighbourhood in Montreal’s west end, where they raised two sons, Denis and Benoît. Gaucher, if he was ascetically exacting in his art, enthusiastically enjoyed the good life. He and Germaine travelled extensively, collected pre-Columbian art, cultivated exotic orchids, and built a Zen garden. His humour was wry and his studio conversation a mixture of dead seriousness and mischievous evasion, especially when the topic was his own art practice. He was a tough negotiator with his dealers, sometimes breaking with them precipitously and bitterly.

Always individualistic in his stance, Gaucher was nevertheless a prominent figure on the Canadian art scene. In 1966 he was appointed assistant professor at Sir George Williams University (now Concordia University), where he taught printmaking and then painting until his death. He was a prominent member of Canada Council of the Arts advisory committees and juries, who remembered with particular fondness the late 1960s and the 1970s when juries made studio visits and formed personal relationships with colleagues across the country. In 1981 he was named a Member of the Order of Canada. He died in Montreal on September 8, 2000. The Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal staged a comprehensive retrospective of Gaucher’s paintings and graphic work in 2003.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements