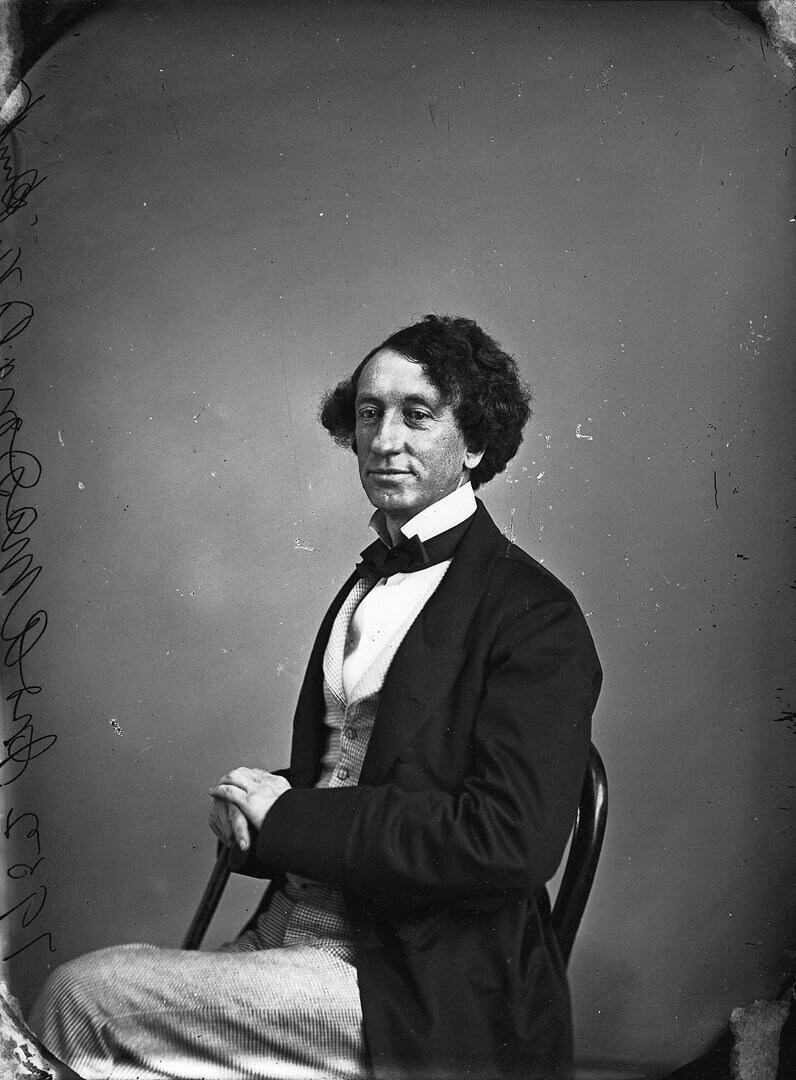

The scale and reach of Notman’s photographic output are unparalleled in nineteenth-century Canada and even in comparison to developments in international centres such as London and Paris. Notman was remarkably prolific and left us with an often lively and carefully observed visual archive of Anglo Canada during a formative period in its history.

Photography as Art

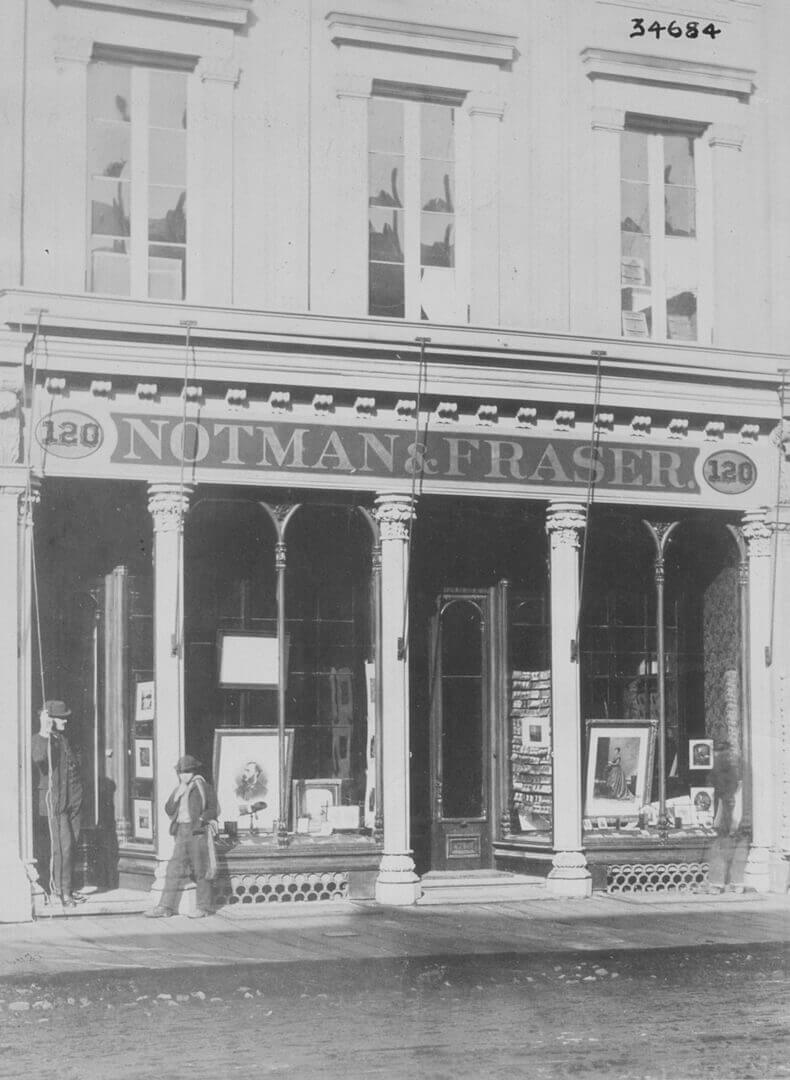

The small brass plaque outside his studio door read “William Notman, Photographic Artist.” This may seem like an obvious identifier now, but the artistic potential of a mechanical medium like photography was the subject of much debate in the nineteenth century. Many asked how someone who pointed a machine, clicked a button, and recorded nature could be considered in the same realm of creative genius as painters who use their imagination to generate images with their own hands.

In the nineteenth century, portraiture and landscapes, like Notman’s Chaudière Falls, 1870, were exceedingly popular, and both benefited from the kind of verisimilitude that photography offered. The popularity of these subjects thus contributed to the new medium’s instantaneous and widespread popularity. In addition Notman did just about everything possible to demonstrate that photography was not a passive endeavour. His studio was a laboratory for technical development, and Notman chronicled these innovations in articles for periodicals, including the influential Philadelphia Photographer. He submitted his photographs to periodicals on both photography and art; his photos often garnered notices, including mention of his more difficult and complicated industrial and landscape projects. He participated in local and international photography exhibitions, winning prizes and accolades. Notman’s efforts raised the profile and quality of photography in Canada and beyond. At the same time, they were instrumental in the success of his business.

Notman’s legacy as an artist has ebbed and flowed. His reputation, like that of many Victorian artists, waned in the first half of the twentieth century as modernism took hold. At the time, few if any art museums collected photography. When Notman’s photographs were reprinted or displayed it was often for their subjects rather than as examples of their creator’s work. Interest in photography began to grow in the mid-twentieth century. In 1951 the prolific Québécois historian Gérard Morisset wrote a magazine article on Canadian photographic pioneers in which he featured Notman prominently. The famed American photo historian and curator Beaumont Newhall cited Morisset’s article in 1955 when he proclaimed Notman to be “Canada’s first internationally known photographer.”

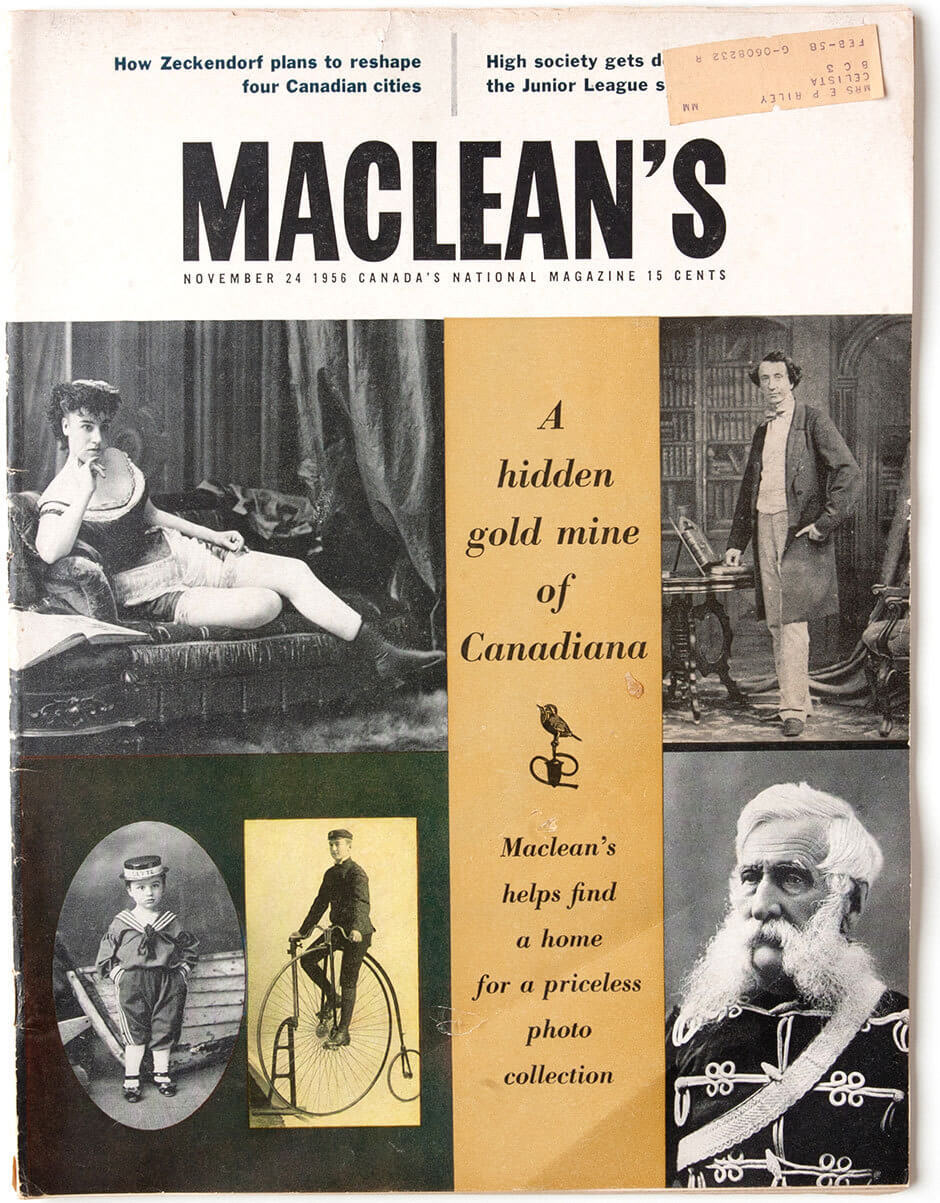

In 1956 a consortium made up of the Maxwell Cummings Family Foundation, Empire Universal Films, and Maclean’s magazine purchased the Notman archive of prints and negatives from Associated Screen News (which had bought them after the business closed in 1935) and donated them to McGill University. They were housed in the McCord Museum, which was managed by the university at that time. Shortly afterward Maclean’s published a series of heavily illustrated and glowing articles on Notman, bringing his career to the attention of a whole new generation.

The value of Notman’s photographs was indisputable as a historical archive, but there was no such consensus on their place in art history. Newhall writes admiringly of Notman’s technical innovations, especially in recreating winter scenes in the studio. He notes that these genre scenes were the source of Notman’s international fame in his own time, but that in 1955 they were prized for their documentary value “as a record of a past age and dying customs.” In 1965 Ralph Greenhill, a collector, photographer, and amateur historian, published Early Photography in Canada, a book-length history of photography in Canada. Influenced by the prevailing modernist and formalist aesthetic, Greenhill had difficulty appreciating Notman’s photographs.

Of Notman, Greenhill writes, “As a photographer he tended to promote some of the worst features of Victorian photography—studio scenes and composites.” These were key areas in which Notman had worked hard to innovate and develop his business. The results were much lauded in their day. Greenhill was unapologetically dismissive of, and rather incurious about, Victorian taste in photography. One can almost feel Greenhill cringing as he writes of the composites: “The results were artificial and were mostly very bad pictures.” Even in the genre of studio portraits, Greenhill found Notman’s work lacking, especially in comparison to the more minimalist studio portraits of his Montreal contemporary Alexander Henderson (1831–1913). Greenhill determines that Notman’s portraits, “with their emphasis on the studio properties, draperies, and artificial backgrounds, appear characterless and formalized, although the best of them do have a period charm.”

In 1965 the McCord Museum hired Stanley Triggs as curator for the Notman archives. A photographer with a degree in fine arts and anthropology from the University of British Columbia, he held the position at the McCord for twenty-eight years, tirelessly working to make sense of the huge Notman archives, which include account books, albums, equipment, ephemera, and over 400,000 prints and negatives. In multiple books, exhibition catalogues, and essays, Triggs published his research on Notman’s life, the workings of his business, and the scope of his photographs. As someone hired to represent the Notman archives, Triggs assessed the photographer’s oeuvre with significantly more insight and generosity than did Greenhill.

Who Took That Picture?

Both Greenhill and Triggs raised an important point about the photographs of William Notman. Although “William Notman” is stamped on thousands of photographs, we cannot assume that all the pictures were actually taken by Notman himself. The common practice among photo studios was to stamp the back with the name of the studio rather than the photographer. A few years after he established the Montreal studio, Notman had assistants working with him and taking photographs. In some cases there are witness accounts of Notman’s activities, and his writings often make reference to specific projects he was personally involved in.

Greenhill saw this difficulty in establishing authorship of individual photographs as another reason not to take Notman seriously as an artist; Triggs, however, sees it differently. Triggs concludes that Notman had personally trained all the photographers who worked with him. He argues that although Notman indeed had a signature artistic style that unified his work as a photographer, it was the “house style” of the studio he had created rather than an individual style. Unlike Greenhill, Triggs describes Notman’s style as forceful and straightforward, with “no redundant or extraneous elements.” Furthermore, he argues, “the entire picture plane is used with economy to tell the story dramatically and describe the subject.”

Ultimately it seems counterproductive to try to link all of Notman’s incredibly varied work based on a particular aesthetic style. As tempting as it might be, the concept of a house style has to be applied very generously to encompass many of the fussy Victorian portraits or touristic landscapes found among images attributed to Notman and his studio. Notman presumably had personal aesthetic preferences, but these pale in comparison to the impressive aesthetic flexibility he displayed across various subjects and over the course of his career. This flexibility was especially valuable because his works were so often imagined and commissioned by clients. Notman’s creativity in working within different parameters to create memorable photographs in many genres is one of the most significant aspects of his oeuvre.

Increasingly, scholars and historians of photography have come to consider photographs as the products of often complex social encounters rather than as the product of specific choices made by the photographer. This would be a particularly useful way to think about Notman’s work. Stepping back and examining the wider context in which Notman functioned enables us to take seriously the commercial and often collaborative context in which he worked. Most of the images he made were commissioned by others, and the final appearance of such images would necessarily have been the product of negotiation between Notman and his client. Those sitting for portraits, for example, were clearly always present and active participants in the process of taking the picture.

Notman was skilled in studio negotiations between photographer and sitter, but from the beginning he also demonstrated a remarkable drive and attendant ability to create photographic opportunities. Recognizing the appeal of belonging to prominent groups, he advertised and grew the field of class portraits as well as images of athletic associations and other markers of bourgeois sociability and success. Notman’s use of composites enabled him to fully exploit this particular market.

Composite photographs were a creative response to a practical problem. Long exposure times necessitated by slow emulsions on the photographic plates made it frustratingly difficult to get interesting and universally pleasing photographs of large groups. Inevitably someone moved, or the whole group ended up looking rigid in their efforts not to move. Photographing a group of students in a meaningful setting like a library was even more difficult given the low light conditions in Victorian buildings. Starting in 1864, for group images, Notman began to photograph sitters separately in his studio. These portraits would be printed and cut out by the art department before being pasted onto a larger photograph or painted backdrop. The completed collage would then be photographed to create the final image. Notman did not pioneer this technique, nor was he the one to introduce it to Montreal, but he and his team of artists developed it in ingenious ways that thrilled his clients, built new audiences, and brought him great fame.

The composite photograph was just one of Notman’s techniques that created an almost theatrical experience for his clients. He carefully designed the most fashionable and elegant studios and advertised sittings as special events. In turn his sitters became full participants in the experience, often presenting themselves in their finest clothes, leaving historians with an impressive archive of Victorian Canadian fashion.

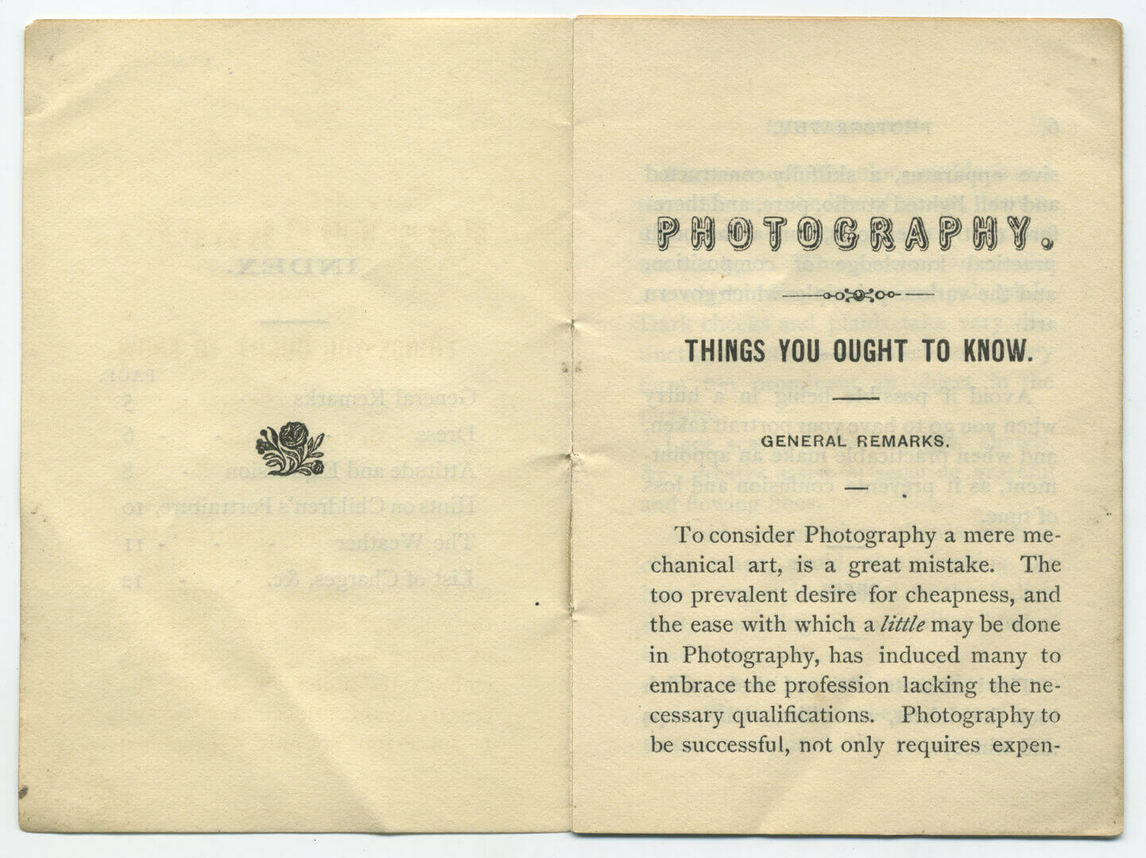

Of course Notman was somewhat of a fashion coach as well as a chronicler. In his helpful handbook for sitters, Photography: Things You Ought to Know, he counsels, “The best materials, and those which look the richest, are silks, satins, reps and winceys…. Dark checks and plaids take very distinctly, sometimes too much so, as they form too prominent an object in the picture. Lace scarfs, open mantles, shawls, etc., greatly assist in securing graceful flowing lines.”

Although photography was his medium, Notman’s significance cannot be limited to that of photographer. He was also a visionary, a facilitator, and the creator of a brand. He built teams. Key to his success was his skill in selecting staff, whether they were the photographic operators (as they were known), or those who ensured that the studio experience was as luxurious as possible, or the artists who enhanced the photographic prints in unique ways. He encouraged technological development and made certain that everything he worked on received extensive publicity. These varied skills do not fit neatly into our mould of the artist as isolated genius, but they do have echoes in modern icons like Andy Warhol (1928–1987) and Damien Hirst (b. 1965).

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements