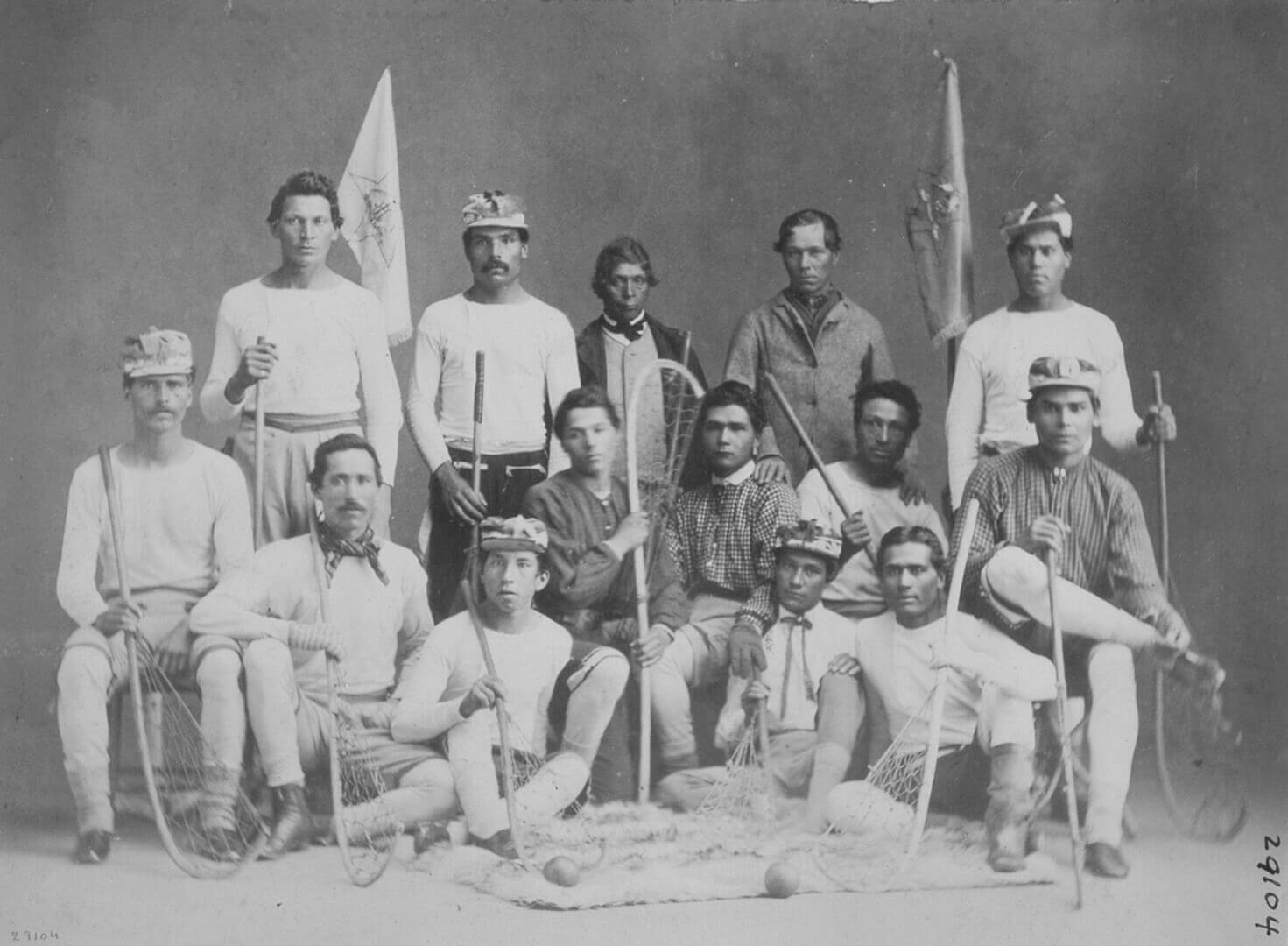

St. Regis Lacrosse Club 1867

William Notman, St. Regis Lacrosse Club, Montreal, 1867

Silver salts on paper mounted on paper, albumen process, 10.1 x 13.9 cm

McCord Museum

French Jesuit priests first documented lacrosse in the seventeenth century, describing it as a ceremonial ritual in the Algonquin and Iroquois cultures. Teams of between a hundred and a thousand players faced off on a field anywhere from half a kilometre to three kilometres in length, with rules negotiated before the game began. The match itself could take up to several days and served spiritual and practical purposes such as conflict resolution and warrior training. The Jesuits disapproved of lacrosse on the grounds that it was violent and involved betting. However, by the eighteenth century French colonists began to play the game themselves, though apparently with little success against indigenous opponents.

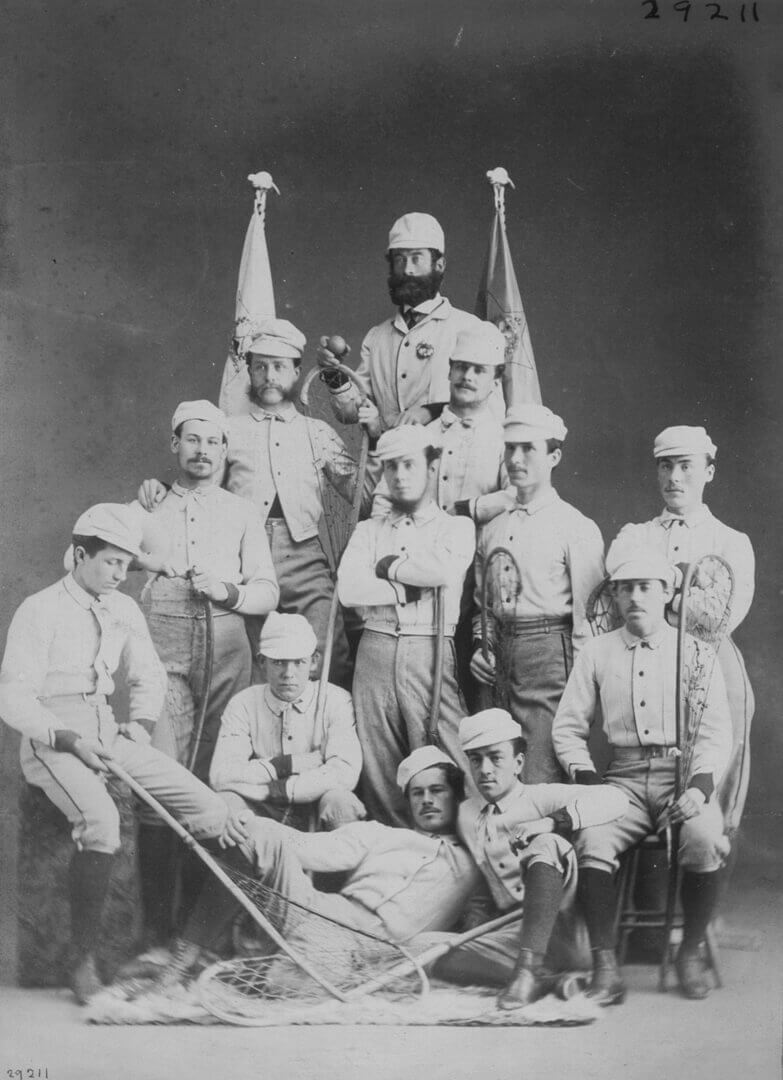

By the mid-nineteenth century the game was absorbed into the Anglo culture of organized leisure sports, which had eagerly adapted to the local pastimes of snowshoeing, skating, and lacrosse. William George Beers, a Montreal dentist, founded the Montreal Lacrosse Club as a teenager, in 1856. By the 1860s he began to codify the game. His rules required that the hair-stuffed deerskin ball be replaced with a rubber one of standard size and that the sticks be standardized. Beers also specified the number of players and the size of the field. This portrait would seem to mark his founding of the Canadian National Lacrosse Foundation and the year the first game was played under his new rules. He was insistent that lacrosse would be the right choice for a national game to unify the country. Confederation provided the perfect moment to make his pitch.

Beers was a regular client of Notman’s, and it seems reasonable to assume that it was Beers who commissioned a series of team photographs of indigenous and Anglo teams as a way of both documenting and promoting the popularity of the sport specifically on his new terms. This was an early and creative use of photography in the realm of marketing. The encounter that generated this photograph would have been an unusual one for both Notman and his sitters. Despite the players being lined up and casually posed under the lacrosse association flags, their arrangement and body language seem awkward, especially in comparison with Notman’s image of the Montreal Lacrosse Club from the same year. The Montreal players seem more comfortable performing for the camera, and yet ultimately the artfulness of their arrangement was the domain of the photographer. It would have been Notman who directed each man in his position and pose. In turn they seem to have willingly submitted to his familiar and respected authority.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements