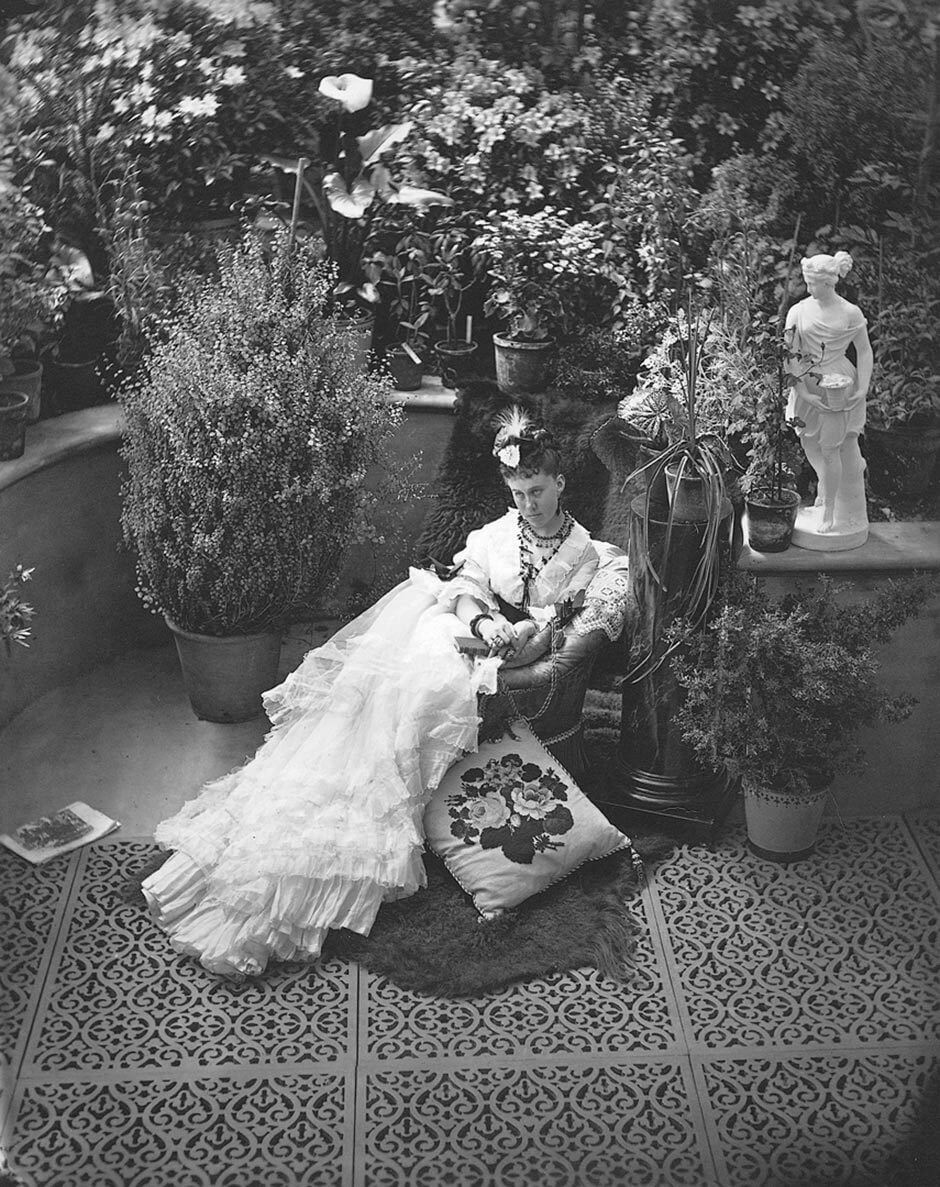

Mrs. William MacKenzie in Allan’s Conservatory 1871

William Notman, Mrs. William MacKenzie in Allan’s Conservatory, Montreal, 1871

Silver salts on glass, wet collodion process, 25 x 20 cm

McCord Museum

Like Harriet Frothingham, Mrs. MacKenzie was a frequent client of Notman’s. Although the 1870s saw Notman more regularly taking sittings outside of his studio, it does seem to have been a perk he reserved for his best clients who were perhaps also friends. Over the course of her sittings for Notman, young Mrs. MacKenzie (Nina, b. 1851) was pictured in some of the most elaborate dresses to be found in his oeuvre. She often posed at angles that ensured a full view of her latest fashion—for instance, turning her body rather awkwardly to show the bustle at the back of her dress. This image was part of a series Notman took in what seems to have been a single day at the home of her father, Andrew Allan, a Scottish-born shipowner and financier. A copy of the Illustrated London News that is incorporated into his portrait is seen discarded on the floor in portraits of Nina and in separate portraits of her brothers.

Other negatives in the archives show that much care and effort went into this day of sittings. Plants and furniture were rearranged. The sitters were moved around, and the photographer experimented with angles. One can imagine that Mrs. MacKenzie must have been pleased with the result. Her dress is displayed to great advantage, and the angle is incredibly flattering.

Mrs. MacKenzie was not blessed with delicate features. She had a large head and a long, full face with quite a prominent nose. But from Notman’s angle above her, these features are softened. Whether to detract attention or just as a personal fashion choice, Mrs. MacKenzie’s style tended to be “too much” even by Victorian standards. Here she wears heavy rings on at least three fingers, a beaded necklace, dangling earrings, and a feathered hat, with a huge white lace dress that all but ruled out walking unassisted. Her personal style is balanced by the carefully arranged assortment of potted plants and accessories in the conservatory.

As in the photograph of Harriet Frothingham, Notman has used a decorative pattern—an iron floor in this case—to add visual interest and anchor the details of the scene. The raised viewpoint and intense use of patterns flatten the space of the picture, rendering a photograph that looks almost like an Impressionist painting. It is difficult to determine just what paintings Notman might have seen in reproductions, but with the added details of the woman reclining, book in hand, the overall effect is remarkably similar to paintings by Berthe Morisot (1841–1895) from the late 1860s and early 1870s. Her scenes of the domestic domain and the limited activities of the bourgeois woman were both aesthetic experiments and sociological commentary.

It would be fascinating to know the extent to which Mrs. MacKenzie participated in the design of this scene. Perhaps she brought her needlepoint pillow to be included as testament to her feminine industry, despite the overall appearance of indolence. Is the newspaper tossed aside by design or accident? Did Notman mean to create a visual equation between the lovely white sculpture on the right and the almost equally immobilized lady? It is tempting to read restlessness, boredom, even a striving for more into Mrs. MacKenzie’s portraits. In 1876, while still married to Mr. MacKenzie, Nina ran off to the United States with a man from her social circle in Montreal. She divorced Mr. MacKenzie in 1877, remarried, and moved to Winnipeg with her new husband. All of this was remarkable enough to warrant an article in the New York Times.

This image is a reproduction of the glass negative, from which Notman would likely have printed only a portion of the photograph. In many cases where he seems to have been experimenting with new spaces and backdrops, he deliberately captured more in the image so that he could edit later. Chances are that the final prints from this sitting look decidedly less modern than the negative (as is the case with Harriet Frothingham), but it is interesting to consider this experimental streak in Notman’s practice and see that the results often carry an uncanny resemblance to artistic trends in other media.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements