William Kurelek garnered national attention in postwar Toronto for his distinctive figurative painting and photographically influenced pictorial compositions. Working and exhibiting within a milieu of established and emerging contemporary trends ranging from abstract painting to performance art, Kurelek—as figurative painter and picture framer—projected the image of a medieval craftsman for the modern age.

Paint Craft

Kurelek defined his creative identity in terms of a somewhat one-dimensional view of medieval art. According to Kurelek, the medieval artist “wasn’t so awfully conscious of art or of being an artist” as he was a “craftsman,” a “picture maker.” The distinction reflected a religious position: it undercut notions of artistic individuality, allowing Kurelek to claim he simply worked for the greater glory of God. Such self-identification distinguished Kurelek’s practice from Toronto modernist artists who also exhibited work at Isaacs Gallery in the 1960s and 1970s, such as Michael Snow (b. 1928), Gordon Rayner (1935–2010), Joyce Wieland (1930–1998), and Greg Curnoe (1936–1992).

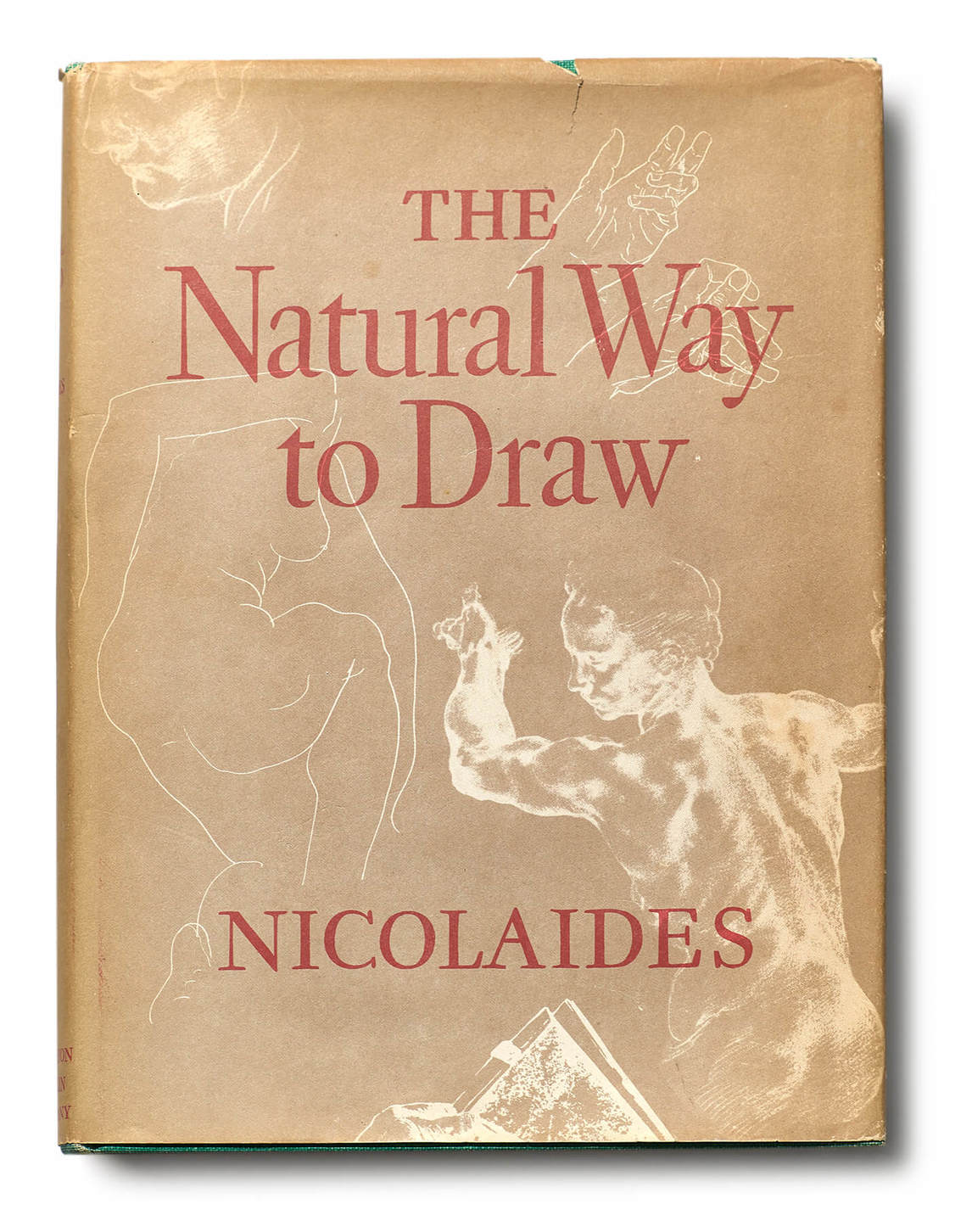

Kurelek also characterized his practice as lacking formal rigour. In 1962 he wrote, “I’ve had little full dress art training; my colour, composition, method of paint application, were arrived at mostly by intuitive groping rather than by systematic scientific enquiry and practice. In a word, I would not say I am a painter’s painter.” Nonetheless, drawing and draftsmanship are the foundations of Kurelek’s practice. Kimon Nicolaïdes (1891–1938) provided the only art instruction that earned unreserved praise from the artist. Kurelek studied Nicolaïdes’s book The Natural Way to Draw for three months in Montreal before boarding a cargo ship for England in 1952.

The lack of pretension Kurelek intentionally conveyed through the image of the unschooled “picture maker” also extends to his working method. His earliest major paintings, Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, 1950, and Zaporozhian Cossacks, 1952, were completed in oil on panel (“unprimed plywood with pronounced grain”) and Masonite, respectively. This choice of medium is a modern approximation of that first employed by the artists of the early Northern Renaissance to whom Kurelek was indebted, namely Hieronymus Bosch (c. 1450–1516) and Pieter Bruegel (1525–1569).

The nightmarish and self-probing paintings, such as I Spit on Life, c. 1953–54, and The Tower of Babel, 1954, that he produced while in England are painted, for the most part, on paper or illustration board, in watercolour, gouache, or tempera. The formal influence of British (and devoutly Christian) contemporary Stanley Spencer (1891–1959), who often painted in water-based media, may also have informed Kurelek’s choice of medium. Whatever the reason, Kurelek may have quickly discovered that these particular media adapted well to his careful but graphic approach to figuration that he had begun to perfect with Zaporozhian Cossacks.

After he returned to Canada in 1959, as he was completing the 160 works of the Passion of Christ series in gouache, Kurelek gradually transitioned back to using oil on panel, predominantly Masonite, supports. Through the remainder of his career, as curator Joan Murray notes, Kurelek’s preparatory and painting method remained “almost preposterously simple and rough”: “He applied a gesso ground to Masonite board, then either oil or acrylic (sometimes in the form of spray), then outlined the composition with a ballpoint pen. For texture, he used coloured pencils; for fine details, he scratched, or scribbled, or brushed the surface. He finished by adding details in pen.”

The appearance of ballpoint pen, spray paint, and a vibrant, unnatural colour palette in a work such as Not Going Back to Pick Up a Cloak; If They Are in the Fields after the Bomb Has Dropped, 1971, characterizes Kurelek’s final period, beginning in the late 1960s.

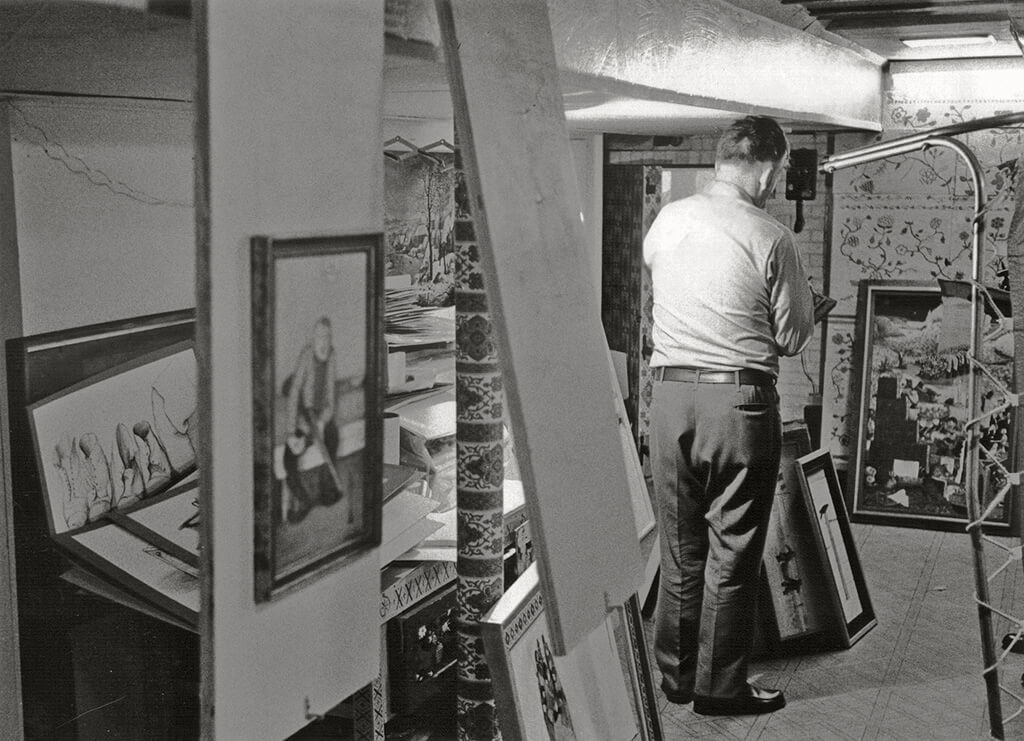

The studio environment he maintained also sustained Kurelek’s image as a “picture maker” craftsman. Kurelek thrived on time and space constraints. He would often combine painting with fasting, and could work for days with little sustenance beyond water, coffee, and oranges.

When he moved to the Toronto Beaches in 1965, Kurelek transformed a former coal cellar in the basement into his studio. He constructed cupboards to store his paintings and tools and decorated the walls and ceiling with elaborately carved and painted Ukrainian designs. Despite these embellishments, Kurelek’s windowless studio was small, measuring roughly one by two metres, and remarkably spartan. He executed the majority of his paintings on his flat worktable.

Inside and Out: Kurelek’s Pictorial Composition

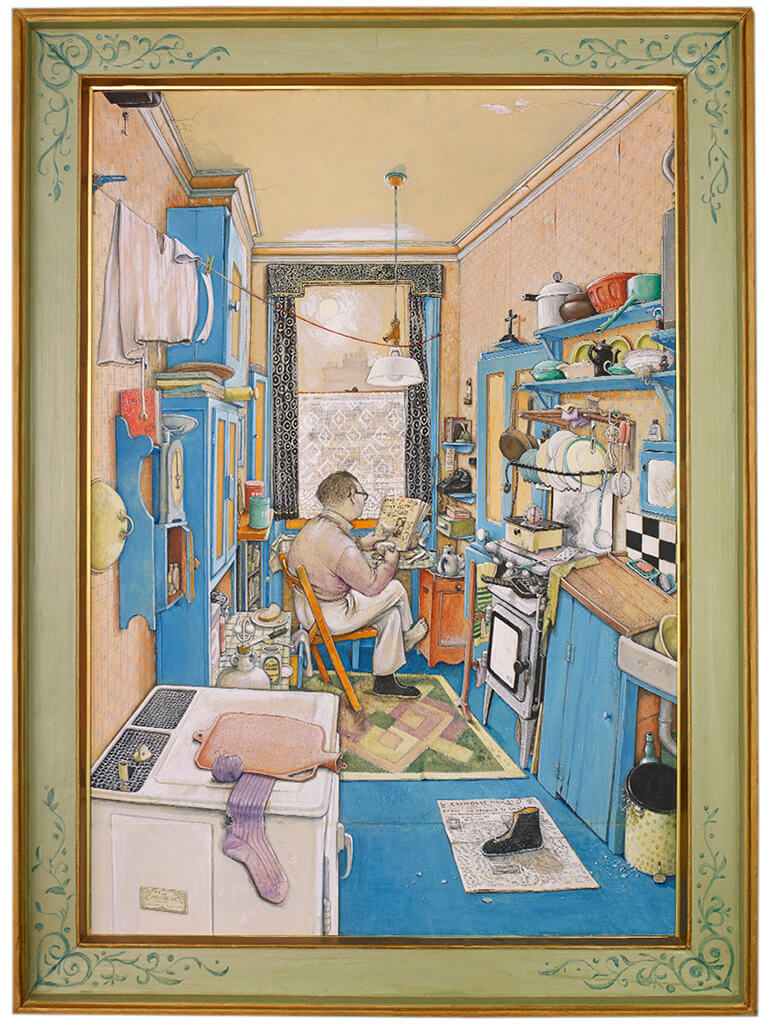

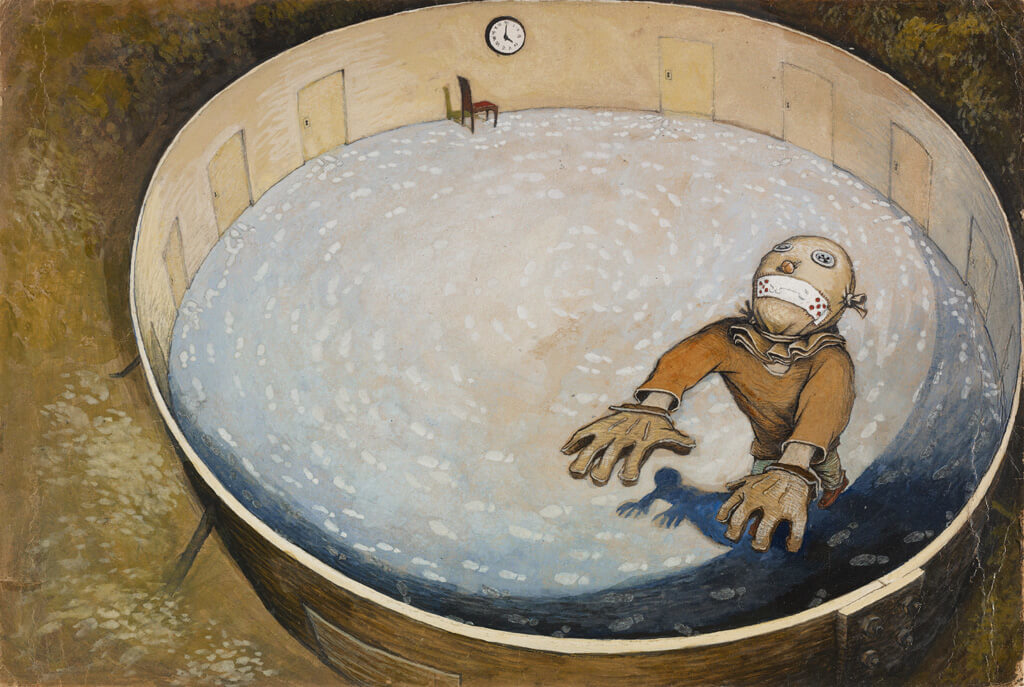

“The message is the most important thing in the picture for me,” Kurelek explained in a 1962 interview; “experimentation is secondary.” Nonetheless, in order to achieve his intended message, Kurelek needed to become adept at pictorial composition so he could seamlessly blend style and content. Kurelek’s paintings reveal what curator Tobi Bruce describes as the artist’s particularly keen sense of “pictorial staging.” Whether the setting is a claustrophobic interior, as in his 1955 work The Bachelor, or the flat, open Canadian prairie, as with The Devil’s Wedding from 1967, Kurelek marshalled both style and composition to dramatic effect.

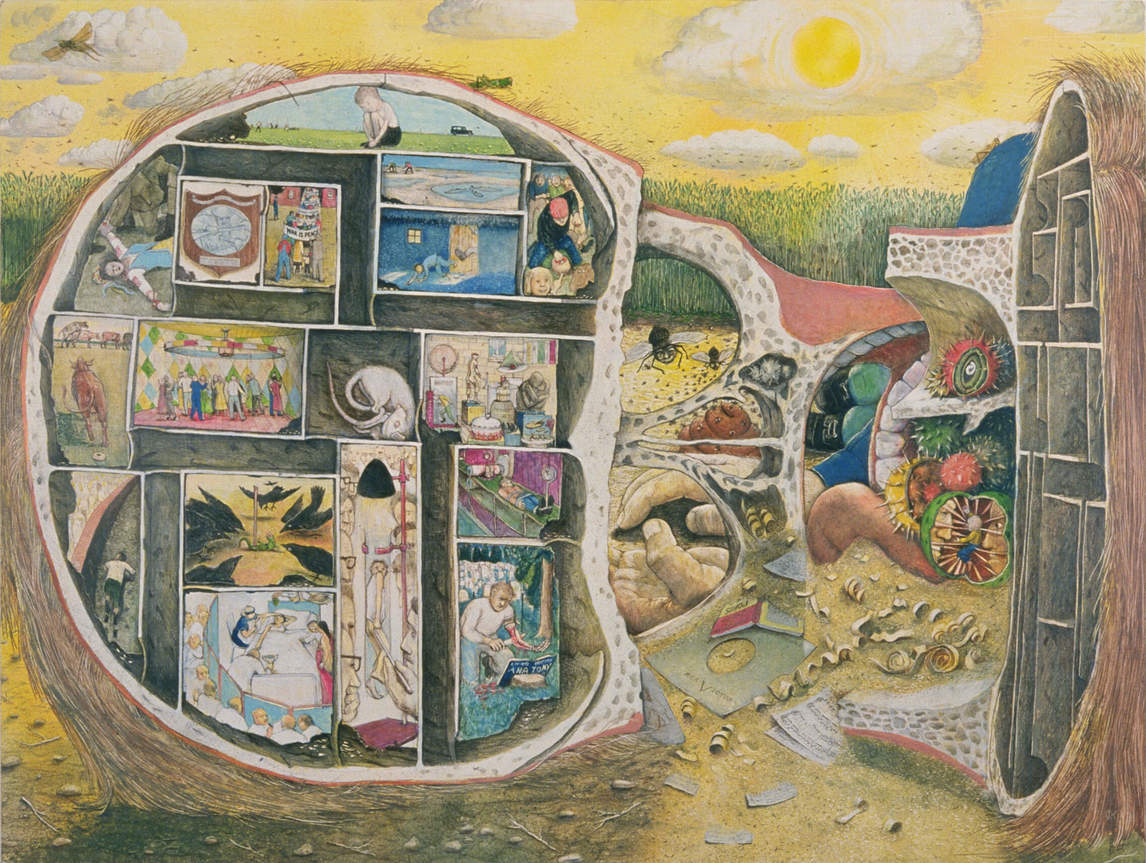

Kurelek’s paintings from the 1950s reveal two distinct compositional strategies. In works like The Maze, 1953, I Spit on Life, c. 1953–54, and The Tower of Babel, 1954, the momentum is toward the construction of horror vacui, or “ fear of empty space” leading to visual overcrowding, to convey his interior life—his haunted memory and sense of isolation from the world around him. Simultaneously, in works like Where Am I? Who Am I? Why Am I?, c. 1953–54, and Lord That I May See, 1955, Kurelek represents the equally bleak world outside his own mind. Solitary figures roam barren landscapes, groping blindly for answers in an empty world. In his 1957 Self-Portrait Kurelek sets himself before a painted collage of photographs, postcards, artworks, and quotations that combine images relating to his inner life and the external world and together announce the new direction his life was to take following his conversion to Roman Catholicism.

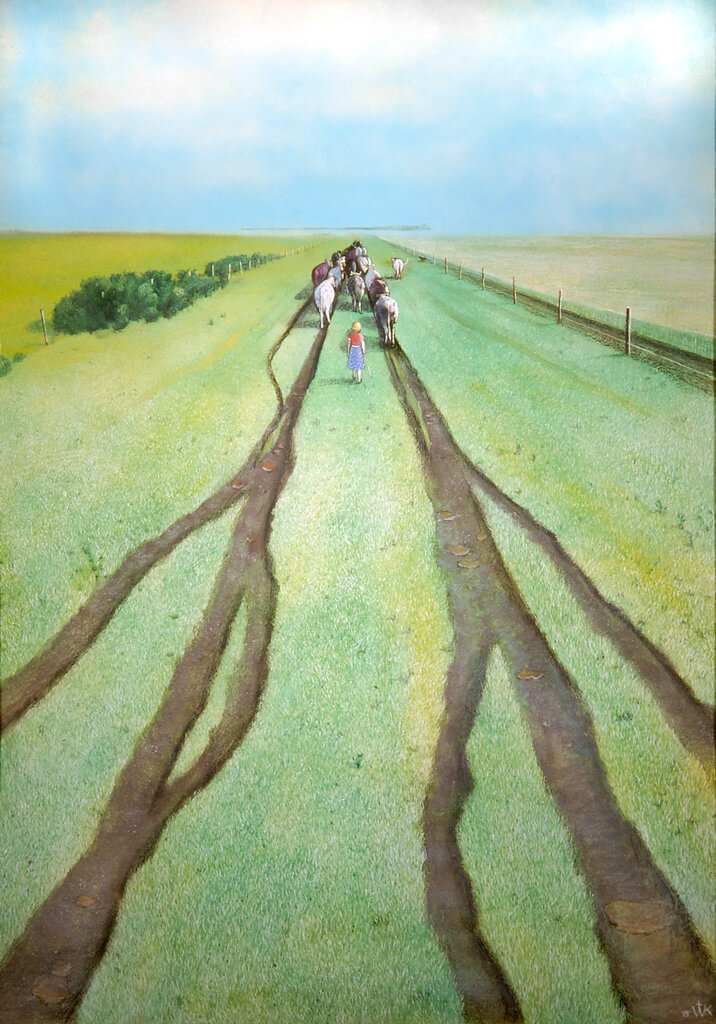

In the 1960s Kurelek continues to develop his earlier compositional strategies, but he relinquishes the solipsistic, interior gaze that characterized his English period from 1952 to 1959. This Is the Nemesis, 1965, for example, uses visual crowding to imagine the chaos and violence of nuclear annihilation. In contrast, in works like The Devil’s Wedding, 1967, the Canadian prairie doubles as a vast, engulfing desert, in the Bible a place of moral testing in which humanity battles Satanic temptation. In both paintings the human beings are actors, represented in particular locations and geographies, but playing roles in a fundamentally metaphysical drama.

Beginning in the 1960s, Kurelek routinely elevates the vantage point, as seen in the six works that comprise The Ukrainian Pioneer, 1971, 1976. His views become panoramic, the ground often appears to pivot laterally toward the viewer, distance is simplified and clarified through one-point perspective, and, with some notable exceptions such as Glimmering Tapers ’round the Day’s Dead Sanctities, 1970, horizons rise and the earth comes to dominate his scenes. By the early 1970s, as seen in paintings such as The Dream of Mayor Crombie in the Glen Stewart Ravine, 1974, and The Painter, 1974, Kurelek abandons the “articulated, volumetric forms and perspectival space” for a rougher, brighter, and flatter pictorial language.

Kurelek boasted of his tendency to “flout artistic rules by doing taboo things like dividing a composition exactly in half,” as in Dinnertime on the Prairies, 1963. He also emphasized the degree to which his creative practice differed from the modernist abstract canvases produced by many of his peers at Isaacs Gallery in Toronto. However, as several commentators have observed, Kurelek’s fixation with the colour and geometric patterns of cultivated land, such as in No Grass Grows on the Beaten Path, 1975, allowed him to integrate figuration with abstraction. Indeed, the large-scale field and prairie paintings he undertook in the 1960s and 1970s bear compositional and stylistic similarity to the more geometric tendencies of Toronto abstract painting, such as Magnetawan No. 2, 1965, by Gordon Rayner (1935–2010).

Celluloid Memory: Film and Photography

Many of Kurelek’s paintings have a theatrical and filmic quality. His paintings often represent figures locked in a dramatic stance, ranging from the dynamic gestures found in Zaporozhian Cossacks, 1952, to the weighted body language of Kurelek’s father in Despondency, 1963. In both cases, he reveals his debt to and appreciation for the kinetic visuals of film and theatre and for the instantaneity of the photographic record. Later in life he also sought inspiration from other painters who relied on photography in their work. Kurelek’s Don Valley on a Grey Day, 1972, represents his response to 401 Towards London No. 1, 1968–69, by Jack Chambers (1931–1978).

Kurelek’s photographic sensibility was forged early, in part as a result of his love of films such as Odd Man Out (1947), Portrait of Jennie (1948), and likely The Picture of Dorian Gray (1945). As curator Mary Jo Hughes has argued, all three films incorporate a central protagonist, often an artist, “attempting to find moral footing.” The artist applied that sensibility consciously for the first time while creating the series The Passion of Christ, 1960–63.

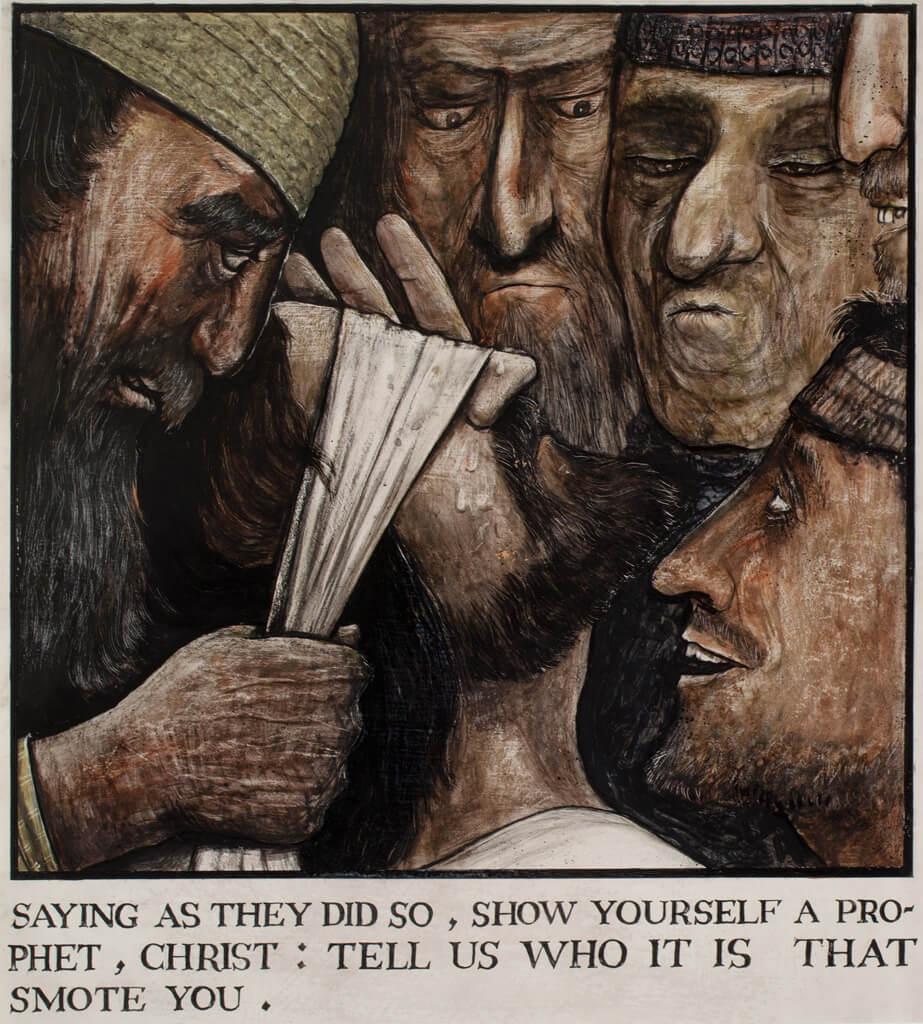

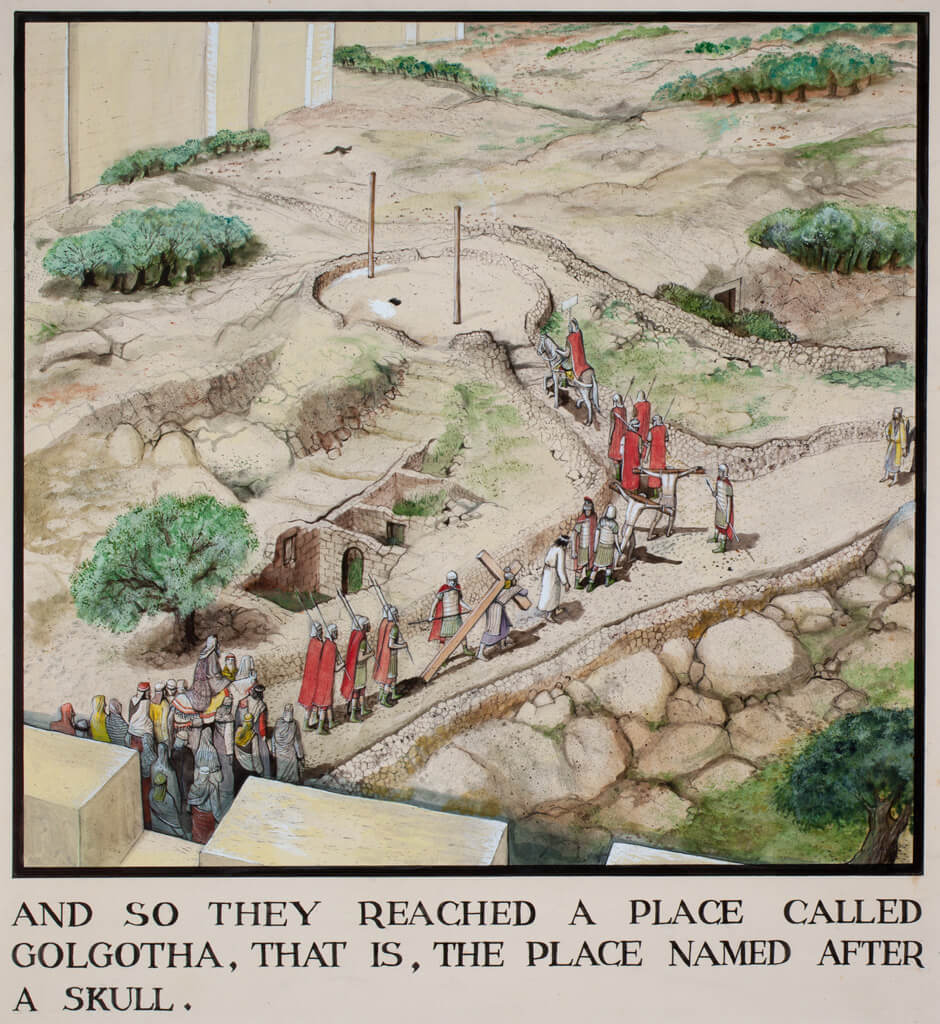

Intending to use the paintings of this series in televised broadcast, Kurelek deployed a number of cinematic devices: dramatic lighting and shadow (And About the Ninth Hour …), contrasting close-up (Saying As They Did So …), panoramic views (And So They Reached a Place Called Golgotha …), and thematic montage, or what he called “projection,” to images other than what is literally described by the main text (Whereupon Jesus Said to Him, Put Your Sword Back into Its Place …). The series is an amalgam of constructed images, each serving as a filmic still, a record of a particular moment and movement frozen in time, and selected to dramatize and advance the narrative.

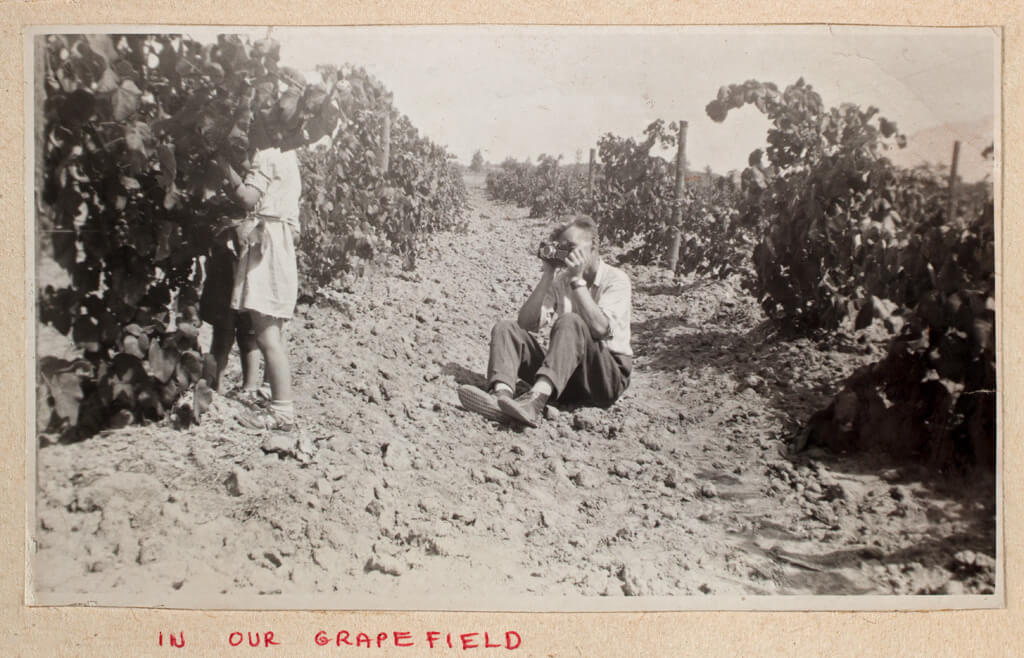

Still photography became a vital tool, the “trusted and omnipresent pictorial aid,” that helped Kurelek recreate the youthful recollections that dominate his “memory” paintings of the 1960s and 1970s; works like Studying in Winnipeg, 1964, and My First Winter in the Bush, 1973. The camera became so central to his painting practice because Kurelek conceived his own memories in photographic terms. The memory was the key image, and the artist’s mind could then “shift the frame to get the best composition.” Of course, Kurelek acknowledged that memory betrays: “My father noticed details I’d missed or got wrong, like the way a certain machine was put together” in a painting. The camera was introduced to his creative practice to minimize the mistakes of recall. Kurelek did train his Asahi Pentax Spotmatic on the details of a scene, but he began to use photography more often as a general compositional guide.

After his death, some four thousand of Kurelek’s black and white prints and colour slides, along with three photo albums, were deposited at Library and Archives Canada in Ottawa. Many of the images document the artist’s return and recurring pilgrimages to Western Canada, beginning in the mid-1960s. Some were taken from a speeding car, capturing transitory motion and the immediacy of being on the road. Most are static shots that record the minimalist designs of the agrarian landscape and reflect information on light, proportion, perspective, and the compositional strategies that are easily recognizable in a Kurelek landscape like Piotr Jarosz, 1977. As part of the artist’s visual resources, the photographs evidence the authenticity of his paintings, with Kurelek the painter assuming the role of location record keeper.

Frames: Expanding the Picture

Until recently, photographic reproductions of William Kurelek’s paintings rarely included the frames that surround them. This absence is significant because the artist expertly fashioned, often unconventionally, many of his own frames. In many cases his craftsmanship lends symbolic enrichment to his paintings. Occasionally the frame is a literal extension of the painted image. Kurelek regarded his framing practice as parallel with his painting practice, befitting the artist-as-craftsman identity he claimed, in opposition to the “purist philosophy of art” of his peers that he vocally rejected.

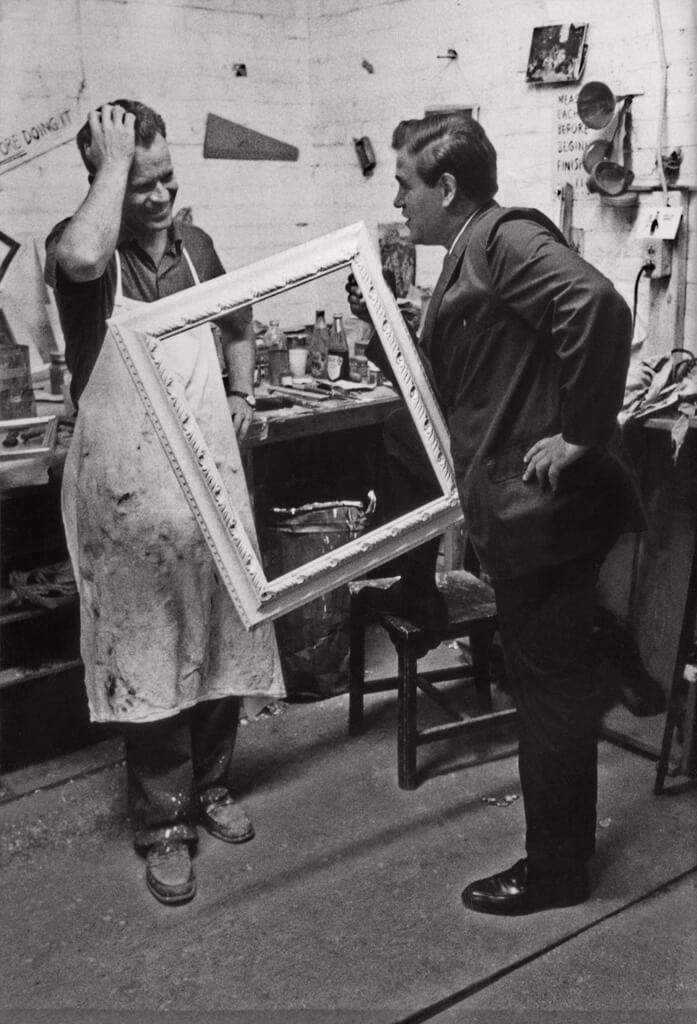

Kurelek began designing and constructing picture frames in London, England. In late 1956, during the months leading up to his formal conversion to Roman Catholicism, he was hired by F.A. Pollak Ltd. Though he had no framing experience, he impressed his new employer with his attention to detail in the trompe l’oeil works he had undertaken at Netherne Hospital and begun exhibiting at the British Royal Academy of Art, such as The Airman’s Prayer, c. 1959.

The framing workshop was run by Frederick Pollak, a Jew who had fled Austria during the 1930s in the wake of National Socialism. Pollak’s connection to the European art world was deep. He had completed contracts with the Louvre in Paris, and his workmanship reflected the legacy of picture framing, which was considered a branch of sculpture among European art academies. Frames were designed, constructed, restored, and coloured at Pollak, each job requiring sophisticated training and a precise skill set. Kurelek became a master finisher and considered his two years with Pollak “a continuation of art school,” later adapting many of the techniques he learned—“spattering, smudging, sealing”—to paintings such as Glimmering Tapers ’round the Day’s Dead Sanctities, 1970.

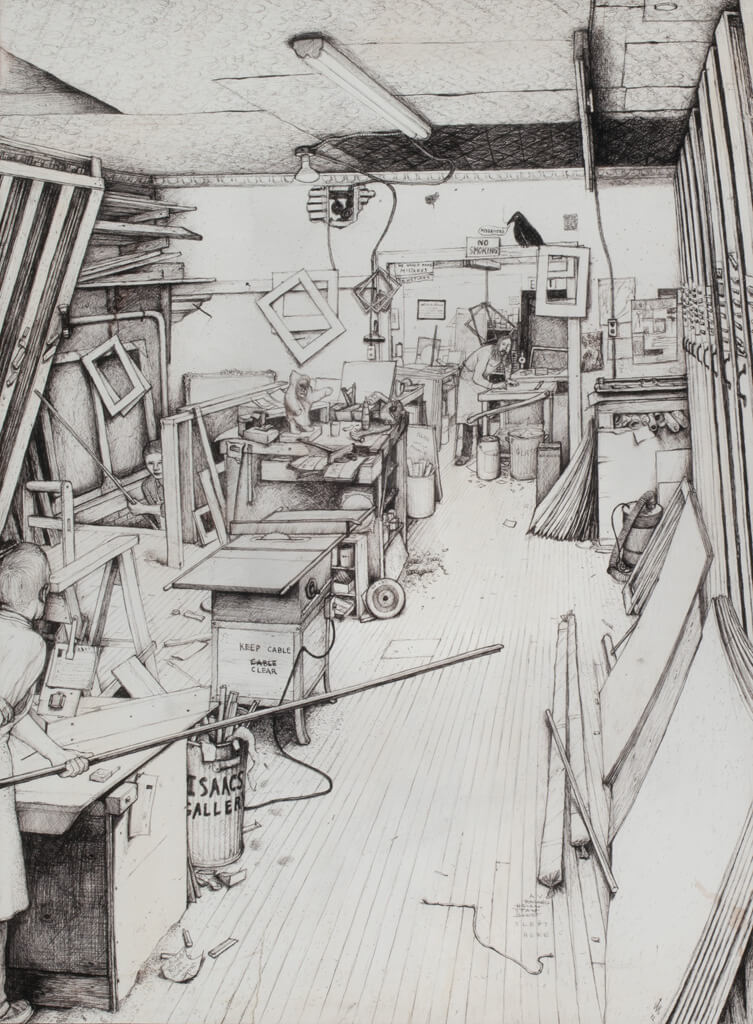

Kurelek’s time at Pollak served him well professionally and creatively. Returning to Canada in 1959, and desperate to begin the next chapter of his life in Toronto, Kurelek was eventually hired as a framer by the young art dealer Avrom Isaacs, whose influence was growing in the Canadian art scene. Although Kurelek was not without considerable framing experience, he reports being hired, once again, on the merits of his artwork. Kurelek secured his first exhibition at Isaacs Gallery in 1960 and worked there as a framer for a decade.

Most of the paintings Kurelek completed prior to 1960 do not feature the artist’s frames. This includes the vast majority of the paintings he made in his English period, from 1952 to 1959. Exceptions to this include Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, 1950, Zaporozhian Cossacks, 1952, and Behold Man Without God, 1955. All three of these works, however, were framed after Kurelek had returned to Canada.

Kurelek’s frames from the 1960s and 1970s follow one of two main design themes. In works like Glimmering Tapers ’round the Day’s Dead Sanctities, 1970, Kurelek carved and painted bold and exquisite motifs derived from Ukrainian folk art into the frame’s frieze. The combination of deep red and lemon-lime complement the dark earth and shimmering northern lights depicted in the painting.

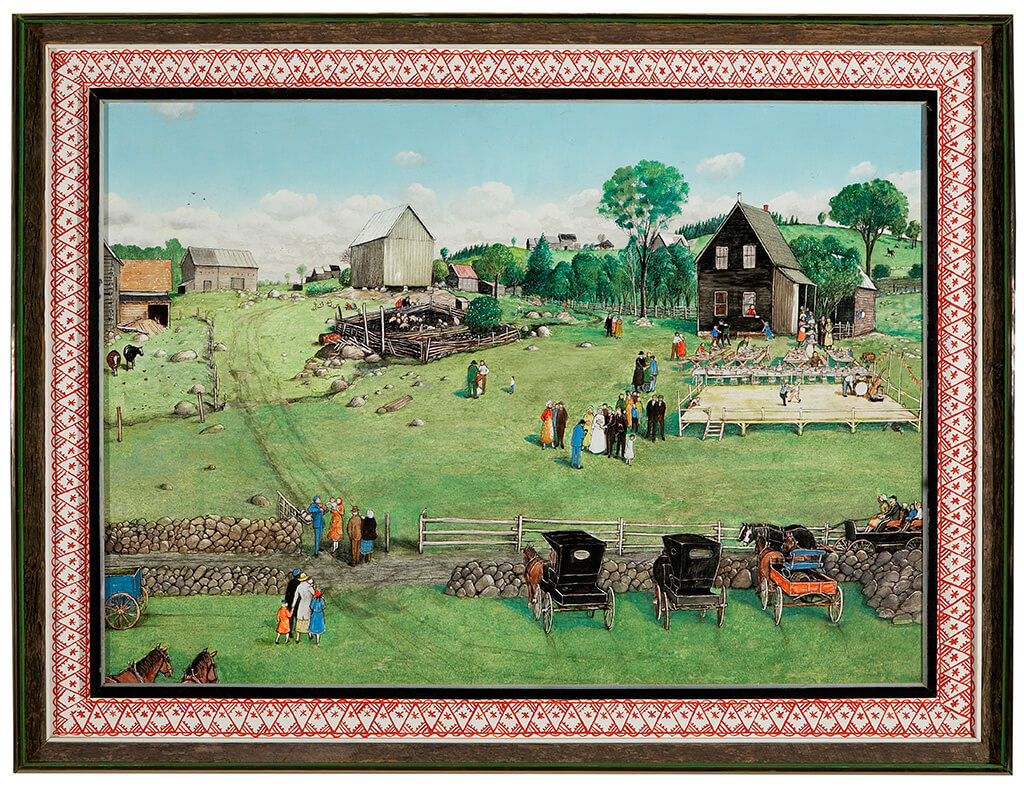

The other element frequently featured in Kurelek’s frames is barn board. In 1964, for his exhibition of the series An Immigrant Farms in Canada—featuring such works as Manitoba Party—Kurelek framed the series in weathered lumber sourced from his father’s farm in Southern Ontario. He continued to incorporate rough, untreated wood in subsequent frames, including Night and the Winnipeg Flood, 1977, until his death.

On rare occasion, the artist also used the frame to expand on a work’s symbolic potency. The frame around This Is the Nemesis, 1965, incorporates a collage sourced from the television schedule published in the Globe and Mail. The Painter, 1974, evokes nationalist sentiment with a frame of maple garland. Finally, Kurelek’s most ambitious frames—those surrounding Reminiscences of Youth and Cross Section of Vinnitsia in the Ukraine, 1939, both from 1968, for instance—literally extend the narrative of the picture by incorporating the frame into the scene itself. Above all, framing was never an afterthought for Kurelek, but an integral part of his picture-making process.

The Series

Kurelek created individual works of lasting significance. However, the artist’s grouping of imagery, his consistent penchant for bringing singular works together to articulate larger narratives and ideas, distinguishes his oeuvre. Binding multiple paintings to a common set of memories, a single historical experience, or enduring moral quandary lent intentional cohesiveness to Kurelek’s solo exhibitions. At times this intent also made his work illustrational, which ran counter to art trends in the 1960s and 1970s but also endeared his work to book publishers. Most significantly, producing series gave Kurelek a sense of interpretive control.

While in England during the 1950s, Kurelek limited his studio production to autonomous, individual paintings. However, these singular works also hint at the artist’s later engagement with series. Motifs of blindness, for example, repeat throughout this period in works that include Where Am I? Who Am I? Why Am I?, c. 1953–54, Lord That I May See, 1955, and Behold Man Without God, 1955. Pre-Maze, c. 1953, is paired with a subsequent work through its titular anticipation of The Maze, 1953. Later, Kurelek replicated several key early paintings in order to incorporate them into series, the most notable of these being The Maze (see The Maas Maze, 1971) and Behold Man Without God (see Behold Man Without God #4, 1973).

After he returned to Canada, Kurelek completed what may be regarded as the artist’s largest and first series: The Passion of Christ, 1960–63. Kurelek’s reliance on a pre-existing narrative distinguishes the Passion series from the original narrative series he would undertake throughout his mature career—the first of which, Memories of Farm and Bush Life, he created in 1962. He followed with Experiments in Didactic Art one year later, and An Immigrant Farms in Canada in 1964. Together, these three series highlight Kurelek’s thematic range. He would go on to produce bodies of work reflecting themes of personal memory (My Brother John, 1973), moral and religious issues related to contemporary life (Glory to Man in the Highest, 1966), and the historical experiences of Canada’s diverse cultural communities (The Ukrainian Pioneer, 1971, 1976).

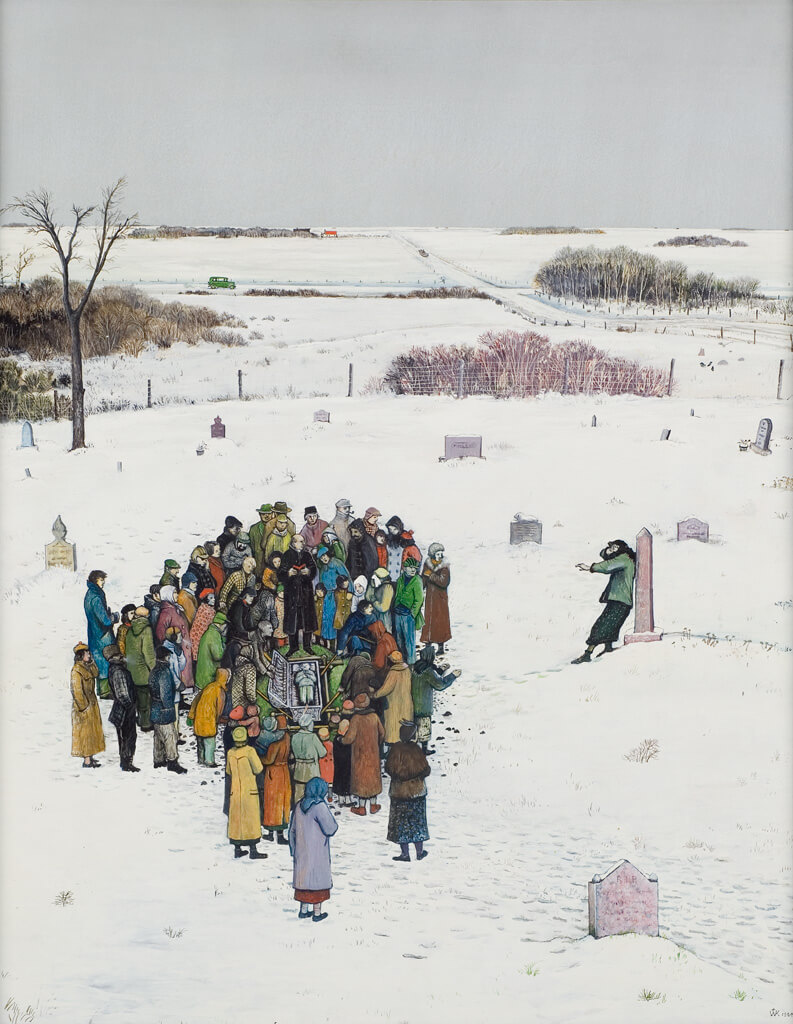

Through title and image, Kurelek’s paintings relay specific stories, and often make terse, ethical propositions that leave little room for interpretive vagueness. For example, in Lest We Repent…, 1964, from the series Glory to Man in the Highest, a scene of inconsolable grief staged within a bleak winter landscape, Kurelek aims to make the viewer reflect on the finality that death must be in a world that does not recognize God and repent. Narrative or didactic texts Kurelek wrote and paired with his paintings when they were exhibited at Isaacs Gallery and elsewhere underline his desire for interpretive control. Along with title, image, and text, the series format allowed Kurelek to shape the audience’s understanding of his painting. Just as writers develop stories chapter by chapter or build arguments by tying together the strands of evidence, Kurelek worked in visual series because he believed it clarified his intentions and enabled his art to convey a certain message.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements