William Kurelek produced impressions of this country, its people and landscape, that have become emblematic of postwar Canada. Religion, the immigrant experience, and the modern ideal of multiculturalism deeply informed his sense of nationhood. He touched on the pressing political and social issues of his day, from the threat of nuclear war to the mounting standoff between religious and secular values, his work inspiring copious praise and vehement critique. Yet much of Kurelek’s art discloses intense vulnerability. Ambitious, prolific, and outspoken, Kurelek was also shy, insecure, and dogged by mental illness throughout his life.

A Religious Painter

Kurelek was an eminently Roman Catholic painter whose faith was deeply personal. The sales of his work helped to fund various religious charities he supported. Lord That I May See, 1955, and other works Kurelek painted around the time of his conversion suggest that religious faith provided him with a sense of direction and purpose he had lacked in his anguished youth.

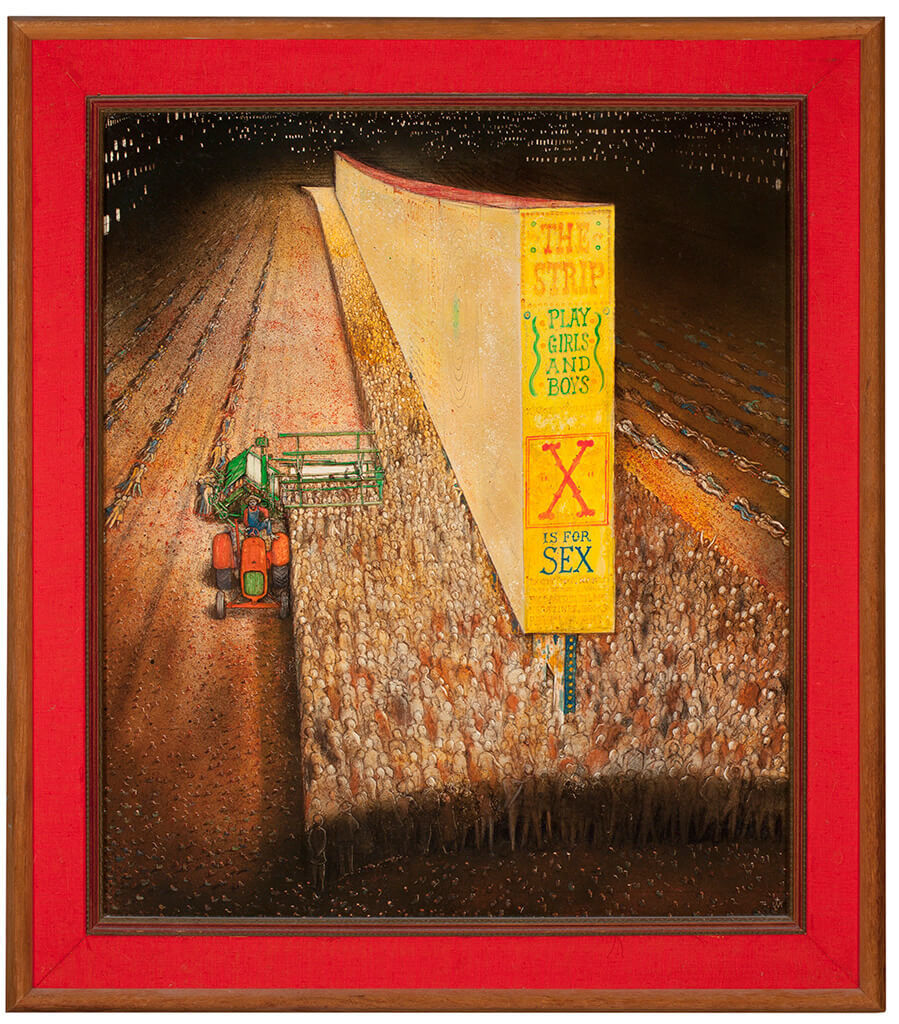

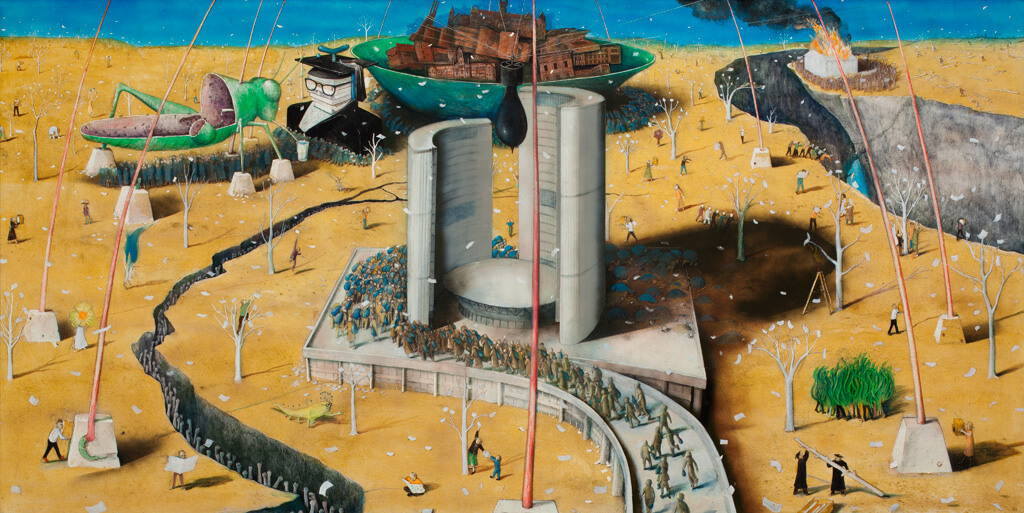

Although many respected and well-known Western artists of the twentieth century reference or depict Christian themes, narratives, and figures, few went as far as Kurelek did to place their work in the service of church doctrine. Titles like Behold Man Without God, 1955, and He Gloats over Our Scepticism, 1972, ring out with the moral indignation of biblical scripture. Indeed, much of Kurelek’s most sermonizing imagery hints at the influence of Edward Holloway, the English theologian with whom Kurelek conferred before entering the Roman Catholic Church in 1957. The violent inflection of some of his religious paintings has earned Kurelek much infamy, but his identity as a religious painter is also expressed by more optimistic works, such as Industry, 1962, and The Hope of the World, 1965.

Many of Kurelek’s religious works display a committed humanitarianism. We Find All Kinds of Excuses, 1964, incorporates a visual leitmotif Kurelek revisited frequently—society’s abandonment of the poor. Kurelek’s concern for the plight of the poor internationally attests to his association with Madonna House, a Catholic apostolic training centre in Combermere, Ontario, which was actively involved in aiding the poor globally. Kurelek visited Madonna House on a spiritual retreat in 1962–63 and found a model for religious living, one that balanced individual spiritual nourishment with a deep sense of engaged social responsibility. Throughout Kurelek’s creative oeuvre, he makes a similar effort to strike a balance between the expression of spiritual mystery and a call for moral action.

Canada and the Cultural Mosaic

Kurelek developed what he later described as his “ethnic consciousness” during public school, around the same time his artistic identity began to emerge. His artistic confidence and ardour for his parents’ heritage was further nurtured by cultural classes he attended as an adolescent and reinforced at university through his involvement in the University of Manitoba’s Ukrainian students’ club and his friendship with Zenon Pohorecky, a fellow student (and future anthropologist of Ukrainian culture) whose art revealed a deep interest in the “interplay between creative pursuit and ethnic identity.”

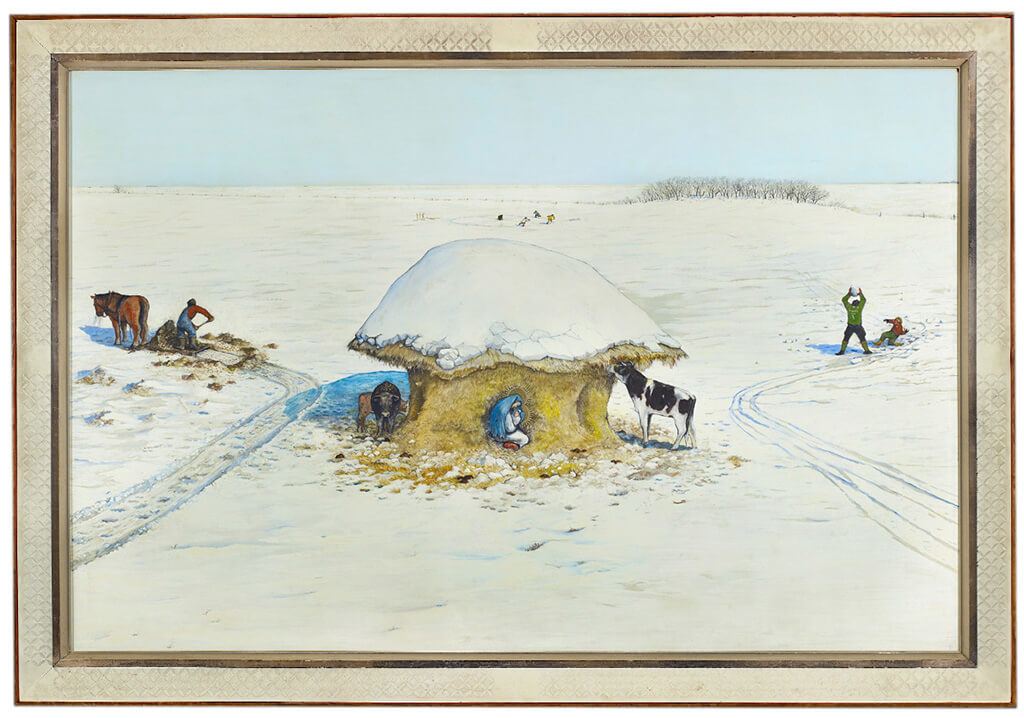

Although matters of social consciousness and the recovery from mental illness became Kurelek’s central artistic concerns during the 1950s, themes of ethnicity and cultural identity appear throughout many of his early works, from Zaporozhian Cossacks, 1952, to The Maze, 1953. His representation of Ukrainian culture became more prevalent in the early 1960s, especially with his 1964 series An Immigrant Farms in Canada. However, it was less a celebration of ethnic identity and more an attempt to honour and repair his relationship with his parents, particularly his father.

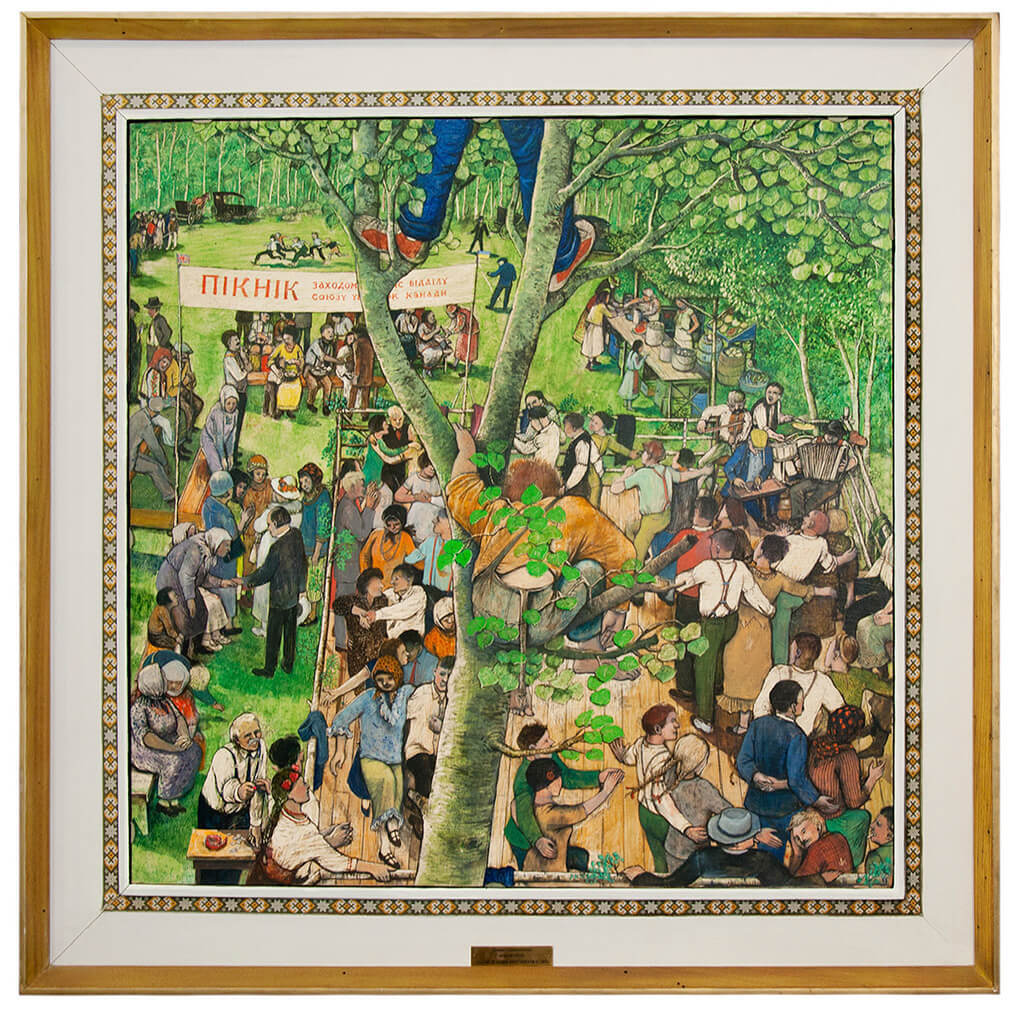

With the approach of the Canadian Centennial in 1967 and the emergence of a multicultural nationalism, Kurelek began to push the discussion of his Ukrainian heritage into one about the history of Canadian nationhood. Between 1965 and 1967 he completed a series about the roles of Ukrainian women in Canada. The timing and public function of it were significant: not only did it serve to mark the fortieth anniversary of the Ukrainian Women’s Association of Canada and the seventy-fifth anniversary of Ukrainian immigration to Canada, but the Ukrainian Pioneer Woman in Canada series, composed of twenty works, including Ukrainian Canadian Farm Picnic, 1966, displayed at the Ukrainian Pavilion at Expo 67 in Montreal, was presented as a Canadian national signifier. In 1983 the federal government acquired and installed the monumental, multi-panelled The Ukrainian Pioneer, 1971, 1976, on Parliament Hill, where it remained until it was transferred to the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, in 1990.

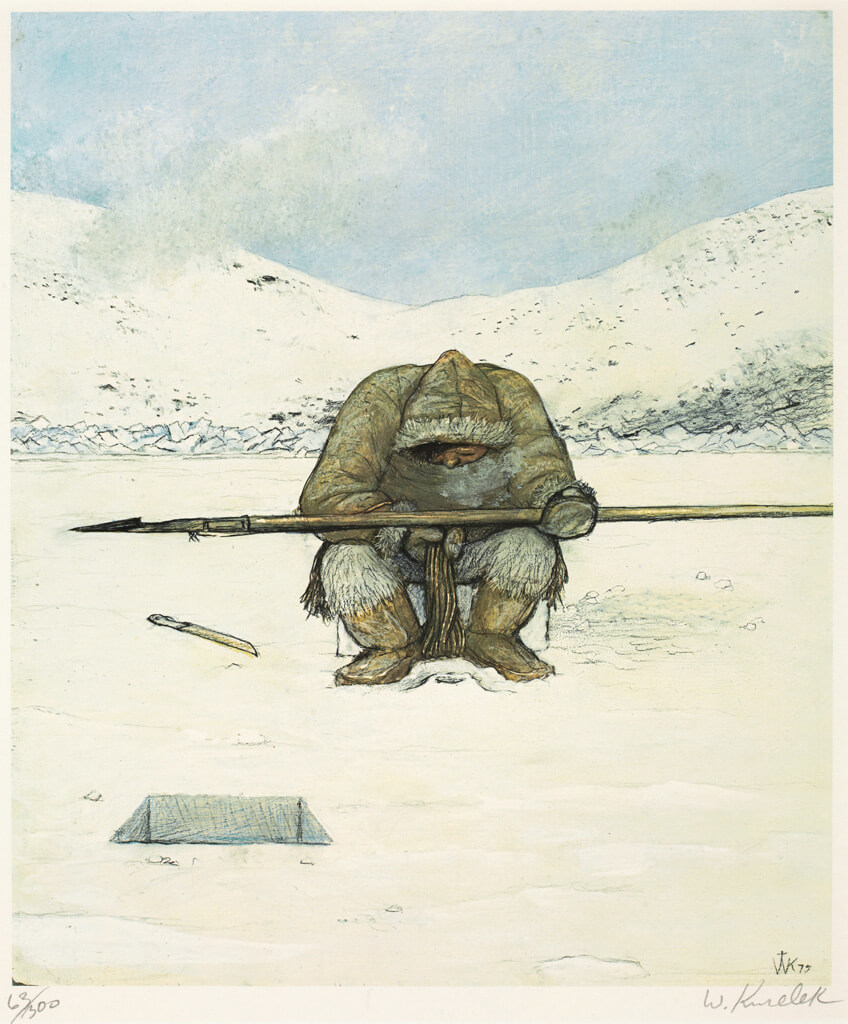

By the early 1970s Kurelek could confidently proclaim that the “days of Anglo-Saxon domination are gone.” He expanded his repertoire in the 1970s to include optimistic expressions of the postwar era’s multiculturalism. He crisscrossed the country on a quest to capture the cultural diversity of the country’s inhabitants and produced series and publications honouring Canadian Jewish, Polish, Irish, Francophone, and Inuit peoples. When he died suddenly in 1977, Kurelek had been planning two series, about German- and Chinese-Canadians, respectively.

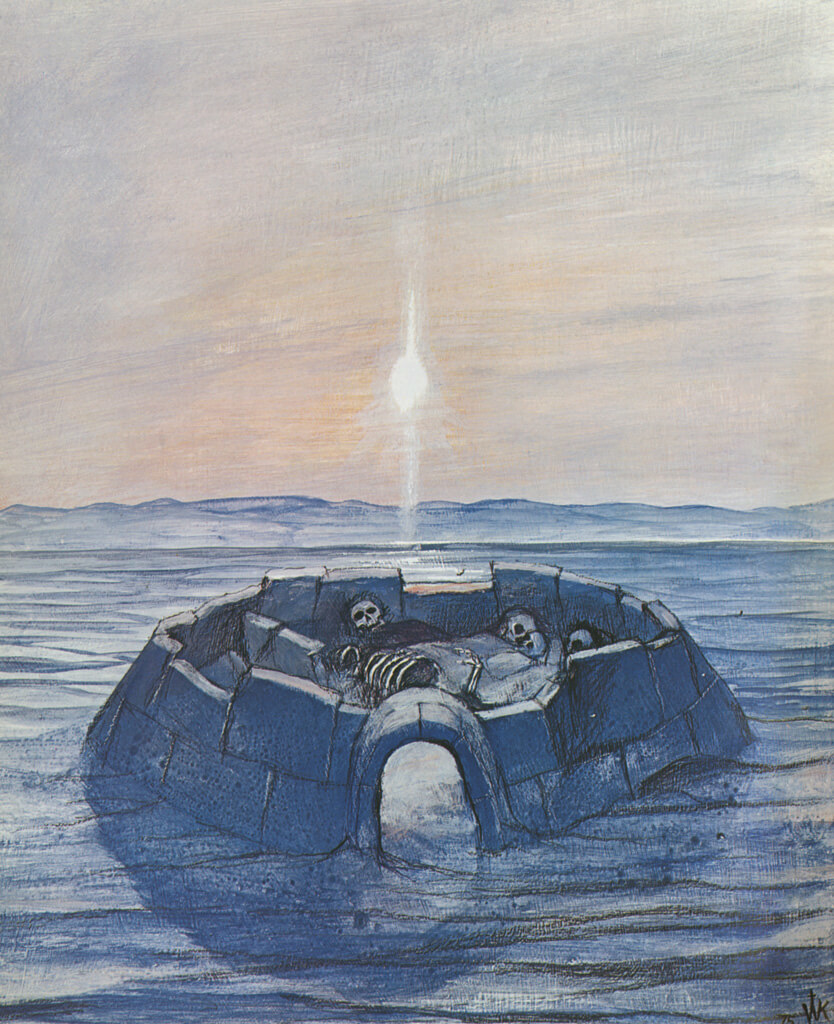

Kurelek’s representations of non-European and Indigenous peoples are not unproblematic. The title of his 1976 book, The Last of the Arctic, for instance, betrays a common misconception, namely that Inuit culture was a static set of beliefs and customs that were disappearing because of infiltrating southern institutions and technologies. Such views were not unique to Kurelek. Christopher Ondaatje, owner of the book’s publishing house, Pagurian Press, had commissioned Kurelek to present a nostalgic view of Arctic life, “to paint it before it had its streetlights and Skidoos and telephone poles.”

Kurelek described himself as an “ethnic artist” and believed his Roman Catholic faith required that he “must respect people of other origins” and “heritage.” What began for the artist as pride for his parents’ cultural heritage had by the mid-1970s expanded to include the lives, histories, and practices of Canada’s contemporary cultural mosaic.

Popular Outsider: Critical Reception

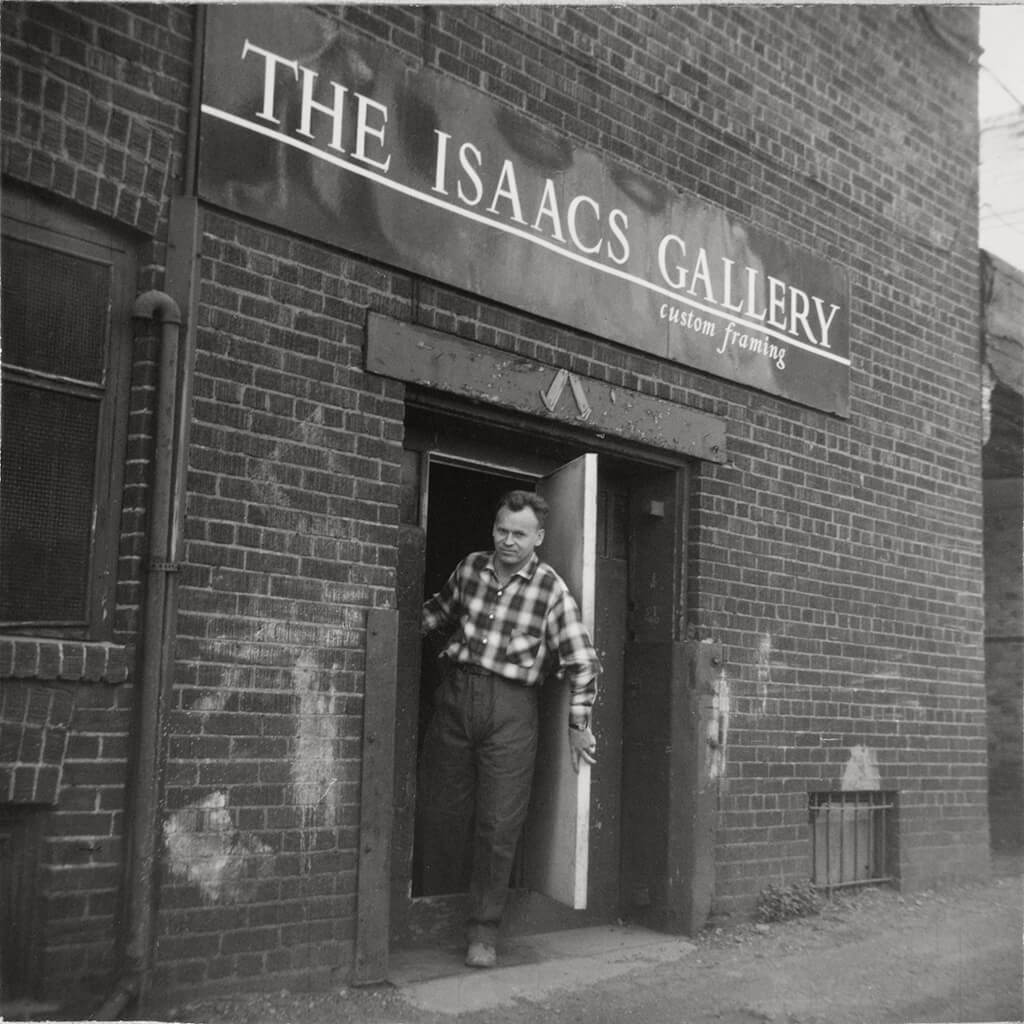

Kurelek began to earn media attention soon after his return to Canada from England in 1959, a decade after he had completed his first major painting—a self-portrait—in an Edmonton basement. The mainstream press exploded with accolades for the artist following his inaugural exhibition at Isaacs Gallery in Toronto in 1960. Critical credit from the media and museum professionals came in 1962 after the internationally respected director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Alfred H. Barr Jr., acquired a Kurelek painting for the institution’s collection.

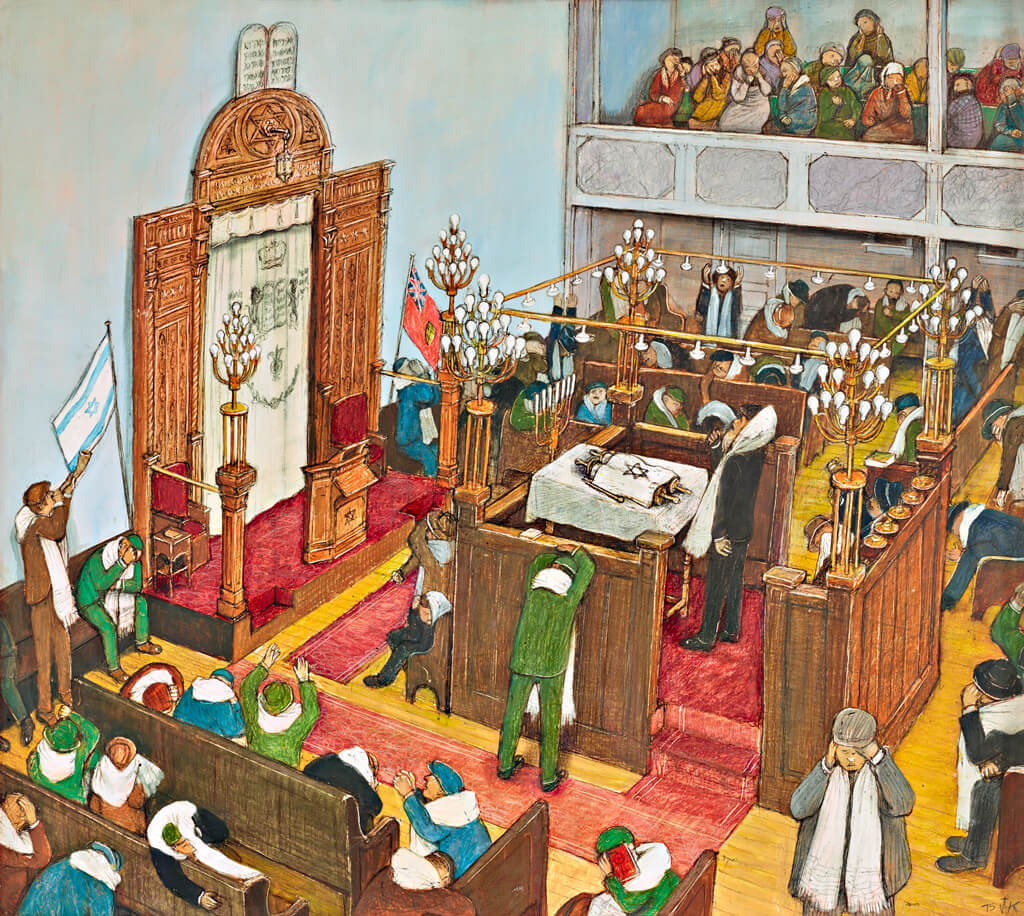

That a certain facet of Kurelek’s creative output was, and remains, popular is easy to understand. His imagery, whether of Ukrainian immigrants toiling on the prairie or of Jewish family life in Montreal, as in the illustration Yom Kippur, 1975, confirmed a progressive view of Canadian society that was strongly resonant between the late 1960s and early 1970s. He portrayed Canada as a mosaic of diverse but harmonious cultures that thrived despite historical inequalities, a harsh environment, and a vast, unyielding geography.

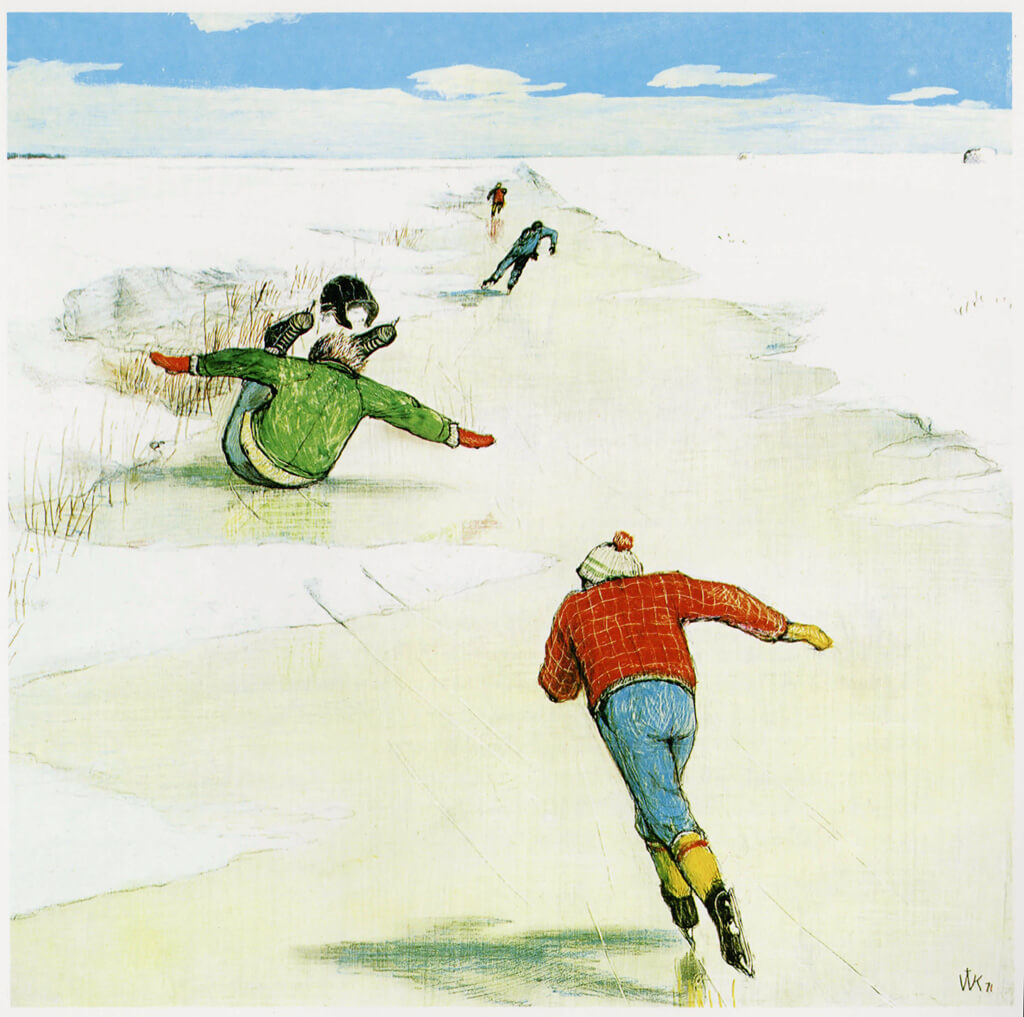

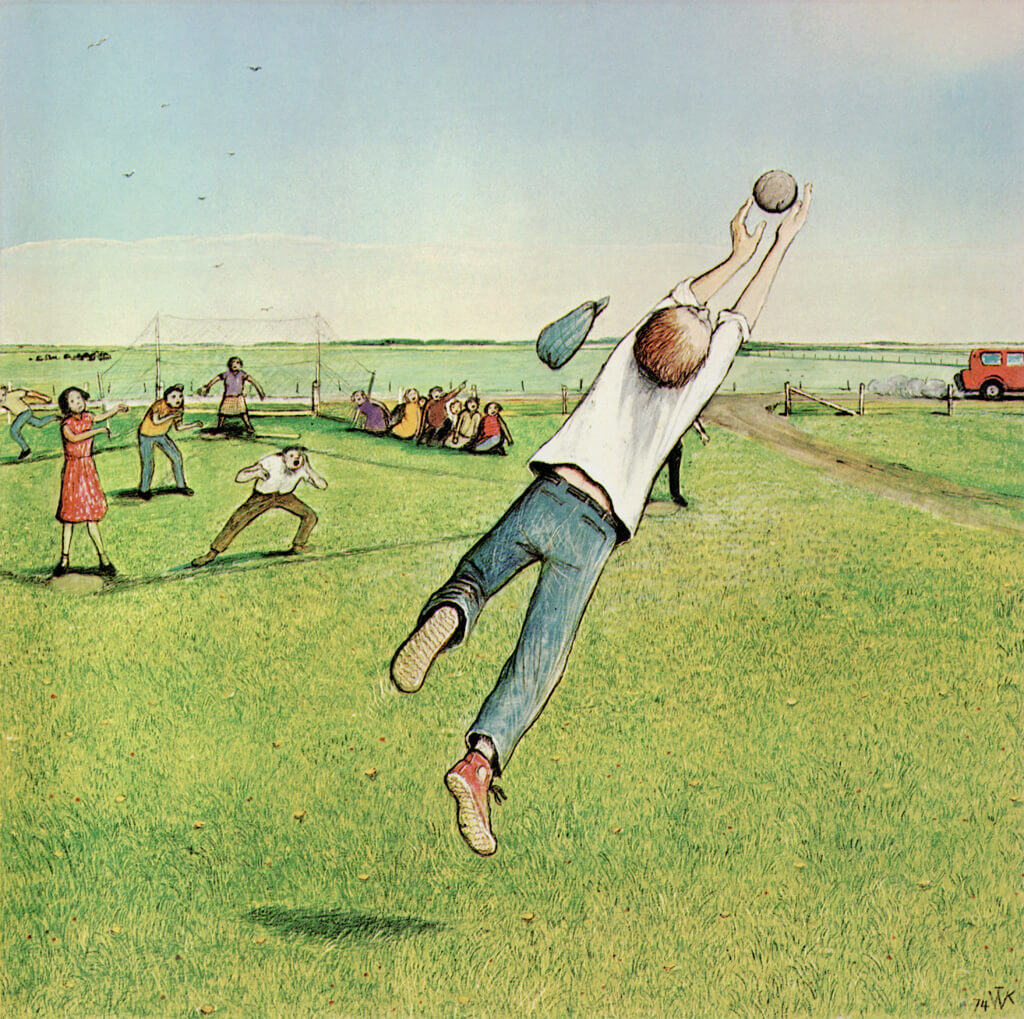

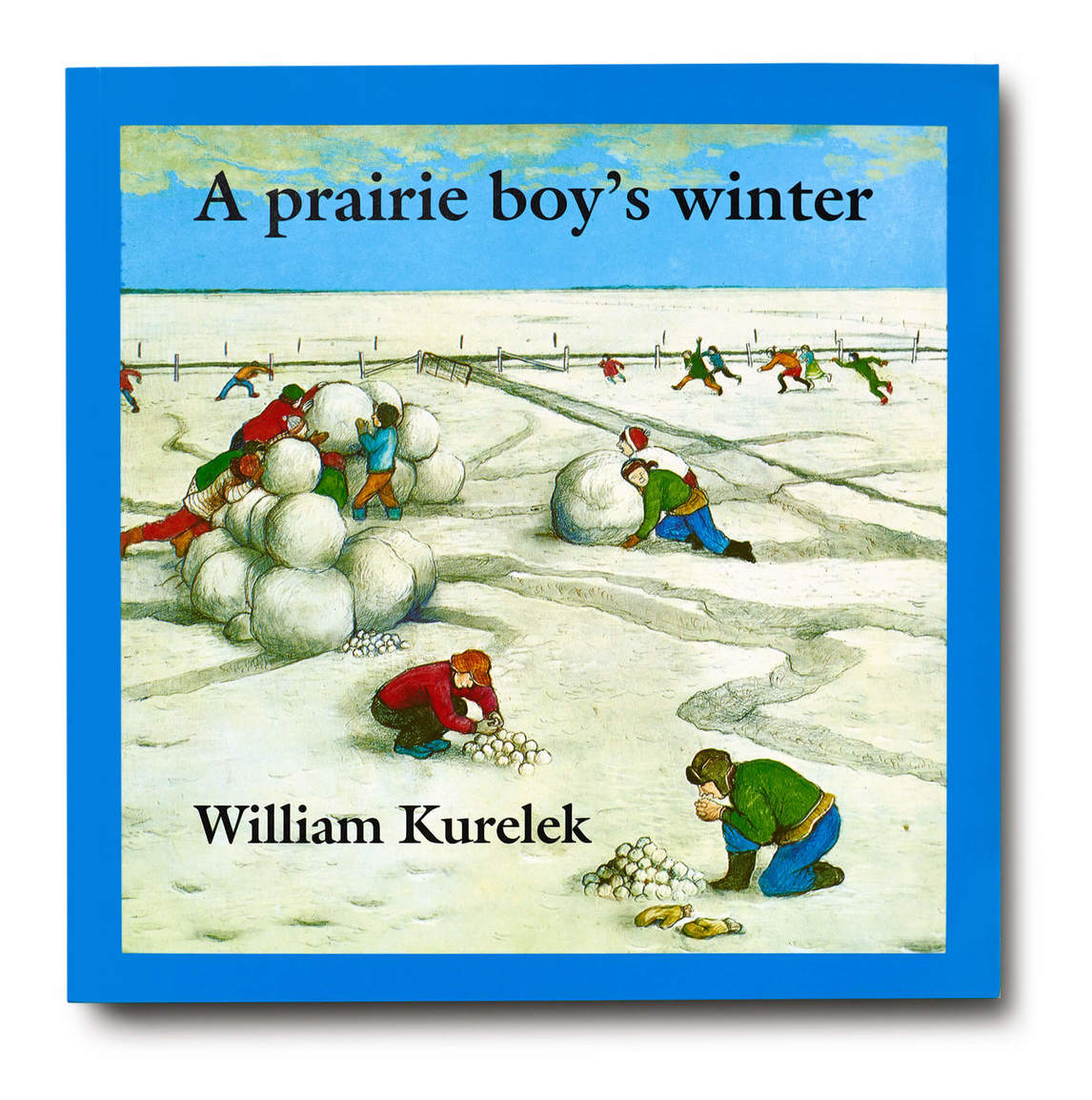

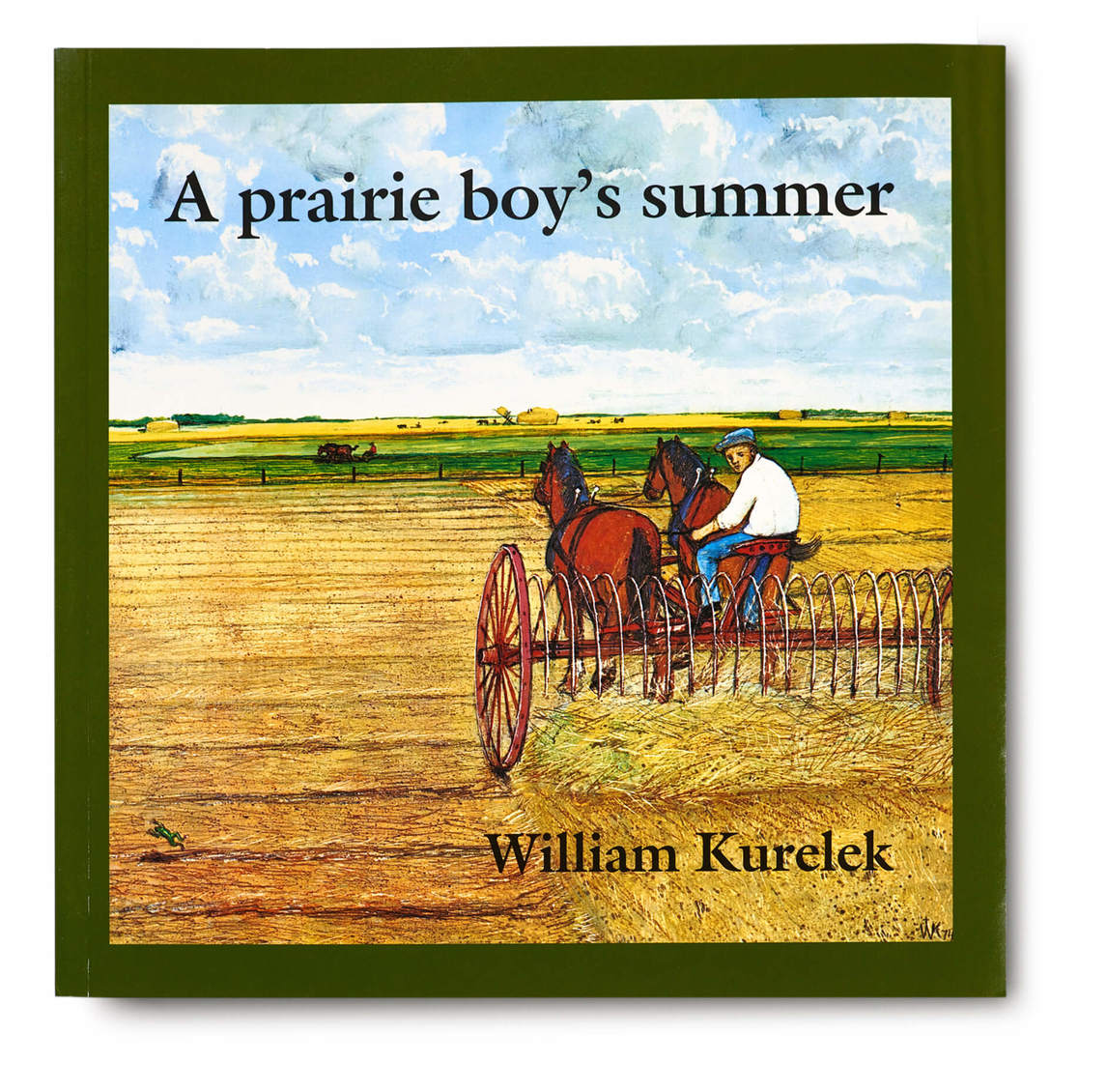

Throughout his career, however, Kurelek was never merely the naive, nostalgic, “happy Canadian” who wrote and illustrated award-winning children’s books. As a conservative Roman Catholic living with the looming threat of nuclear war in the 1960s, he believed that a manmade but divinely ordained “purgative catastrophe” was close at hand. And yet though he “damned with terrifying fervor … often with disturbingly gruesome images,” as critic Nancy Tousley observed, his “nostalgic side … and the work he considered to be ‘potboilers,’” such as his illustrations for A Prairie Boy’s Winter (1973) and A Prairie Boy’s Summer (1975), supported his popularity in the public imagination.

If Toronto’s artistic and intellectual elite were “rather annoyed” by the success of this figurative painter of homely prose and agrarian subjects, as Kurelek’s dealer, Avrom Isaacs, believed, his decision to “put God first” made many within the secular art community apoplectic. Some argued that Kurelek’s moral didacticism interfered with the artistic integrity of his work. Others claimed his views were fraudulent. “Where Kurelek fails miserably,” journalist Elizabeth Kilbourn wrote in 1963, “is when he attempts to paint subjects which he knows about only from dogma and not from experience, where in fact he is a theological tourist in never, never land.” Kilbourn’s sentiments were echoed by critic Harry Malcolmson, who three years later penned what became the most infamous rebuke: “the problem with these pictures is that they flow from Kurelek’s imaginings and not from what he knows.” Malcolmson urged Kurelek to concentrate on farm paintings that reflected his upbringing.

Kurelek’s response to his critics was characteristically indirect. According to his wife, Jean Kurelek, “He was sensitive to criticism but never liked to confront his critics in person,” and would publish a rebuttal or write them a letter. To Malcolmson he explained the source of his conviction: “Our civilization is in crisis and I would be dishonest not to express my concern about my fellow man.” And he added:

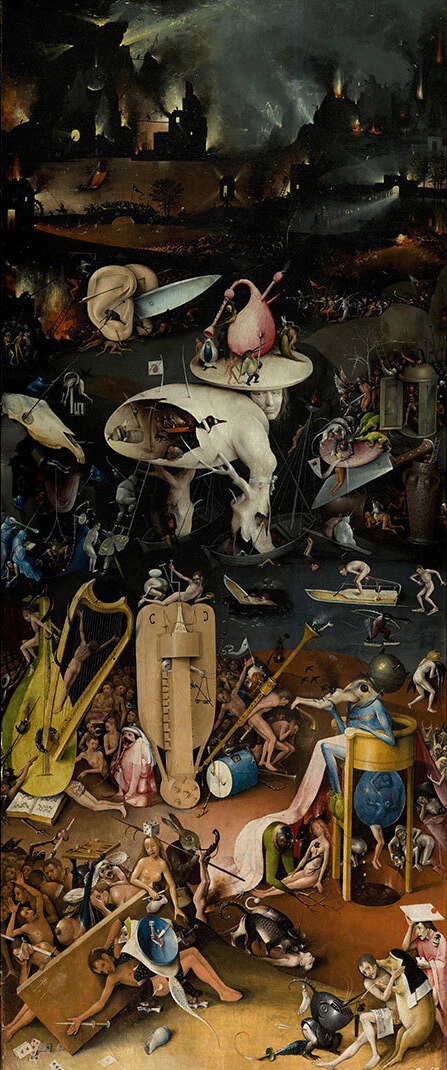

Did Hieronymus Bosch, a recognized master in representation of Hell himself go to Hell, and come back before he tackled it? No one has come back from the dead to record his experiences there and yet great classical writers like Milton and Dante waded right into it. Obviously they must draw their experience of those things partly from similar earthly experiences partly from personal or mystical intuition.

The influence of Hieronymus Bosch (c. 1450–1516) on Kurelek can be seen in works such as Harvest of Our Mere Humanism Years, 1972, and I Spit on Life, c. 1953–54. Despite the detractors, Kurelek earned immense respect from secular peers such as Dennis Burton (1933–2013) and Ivan Eyre (b. 1935), who like Barr recognized his artistic legitimacy. Though Kurelek’s work was a product of his Christian world view, the “somber, menacing quality” of it aligned naturally with the social anxiety and existentialism common in the art world during the Cold War era.

The Word Made Flesh

Kurelek was a prolific writer, whose output encompassed travel diaries and interpretations—often reproduced in brochures at Kurelek’s Isaacs Gallery exhibitions in Toronto—plus letters, speaking notes, and an autobiography. He was also a master illustrator and wrote or illustrated fourteen books in the last four years of his life, including A Prairie Boy’s Winter (1973) and A Prairie Boy’s Summer (1975), which were named among the Best Illustrated Children’s Books of the Year by the New York Times in 1973 and 1975.

Kurelek was not a particularly concise, elegant, or balanced writer, although he could be refreshingly if “excruciatingly frank.” His content was routinely didactic and reflected his belief that the word had greater potential “to convert people” than his visual art. He also made sense of his artistic purpose through theatrical and literary metaphors: “[E]ach believer has his or her role to play in the drama of mankind’s salvation—some just a few lines, others whole pages.” Ultimately, Kurelek’s prose is autobiographical, a scintillating primary record of his experiences, beliefs system, thinking process, and creative motivation.

Kurelek’s first mature body of writing appeared in the late 1940s. The text, a “life story” emphasizing various mental and physical ailments Kurelek suffered, was composed for a Winnipeg neurologist. By the early 1950s Kurelek was in England seeking psychiatric diagnosis and treatment at Maudsley and Netherne hospitals. He wrote as a means of psychotherapy, “continually writing, by a kind of free association method, all the thoughts that came into my head.”

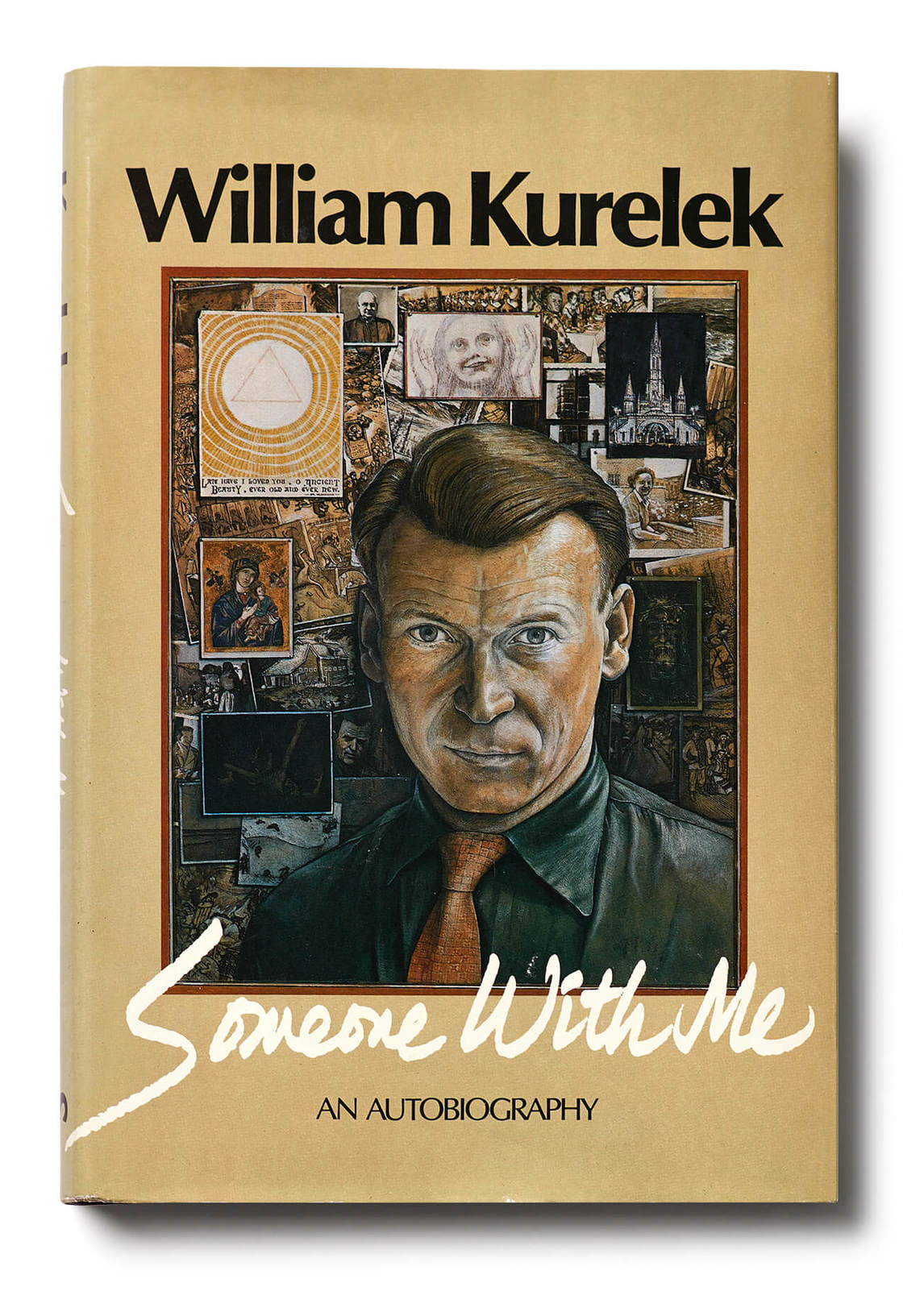

Kurelek’s most significant piece of writing remains his autobiography, Someone With Me (1973, 1980). The first version was published by the Center for Improvement of Undergraduate Education at Cornell University. Cornell professor Dr. James Maas intended the autobiography as a primary source for his introductory psychology course. As such, the rare 1973 edition of Someone With Me amounts to an invaluable but rambling, unedited tome more than five hundred pages long.

The narrative recounts Kurelek’s memories of childhood and adolescence, a rational reconstruction that culminates in his mental breakdown and hospitalization in England and his “comeback to normalcy and success” through religious conversion. A full quarter of the 1973 autobiography is a digressive exploration of theological argument, touching on Darwinism, contemporary politics, scriptural exegesis, and metaphysics. Kurelek was continually tweaking his autobiography up to his death in 1977.

In 1980 Toronto publisher McClelland & Stewart republished Someone With Meposthumously. The book was significantly abridged to 176 pages and eliminated (against the author’s wishes) the original’s concluding theological meditation. Readers reacted to its frank and confessional tone. “Kurelek screams his pain,” one reviewer wrote.

The Maze of Mental Illness

Kurelek’s autobiography, Someone With Me (1973, 1980), paints a vivid portrait of his battle with various undiagnosed ailments throughout his teenage years into early adulthood, including anxiety, depression, and psychosomatic eye pain. His struggle culminates in psychiatric treatment at Maudsley and Netherne hospitals in England, where Kurelek was a patient from June 1952 until January 1955. Kurelek emerges victorious at the end of the autobiography, a successful artist, aided by his treatment experience, but he was convinced that the mystery of faith had ultimately done more to heal him than the science of psychiatry.

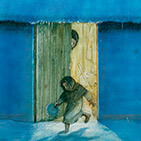

Nonetheless, Kurelek’s relationship to his own mental illness through the language of psychology and psychoanalysis inspired his great, tormented, compartmentalized paintings from the 1950s, including The Maze, 1953, and Behold Man Without God, 1955. In The Maze he represents himself as a rat unable to escape the proverbial behaviourist maze. In Behold Man Without God he wrestles a serpent, the Freudian symbol of sexual drive.

In the postwar era, the massive psychological trauma induced by the Second World War had spurred British psychiatry toward new and innovative treatment models, including art therapy. Surrealism, an avant-garde art movement more widely appreciated, influential, and understood in Britain than in English Canada at the time, was another important catalyst in the treatment of mental illness. European Surrealist artists and writers, most notably André Breton (1896–1966), “valued the freedom of expression of the ‘insane’ and the imagery of the subconscious” and, as a result, were more inclined to conceive art in therapeutic and psychological terms.

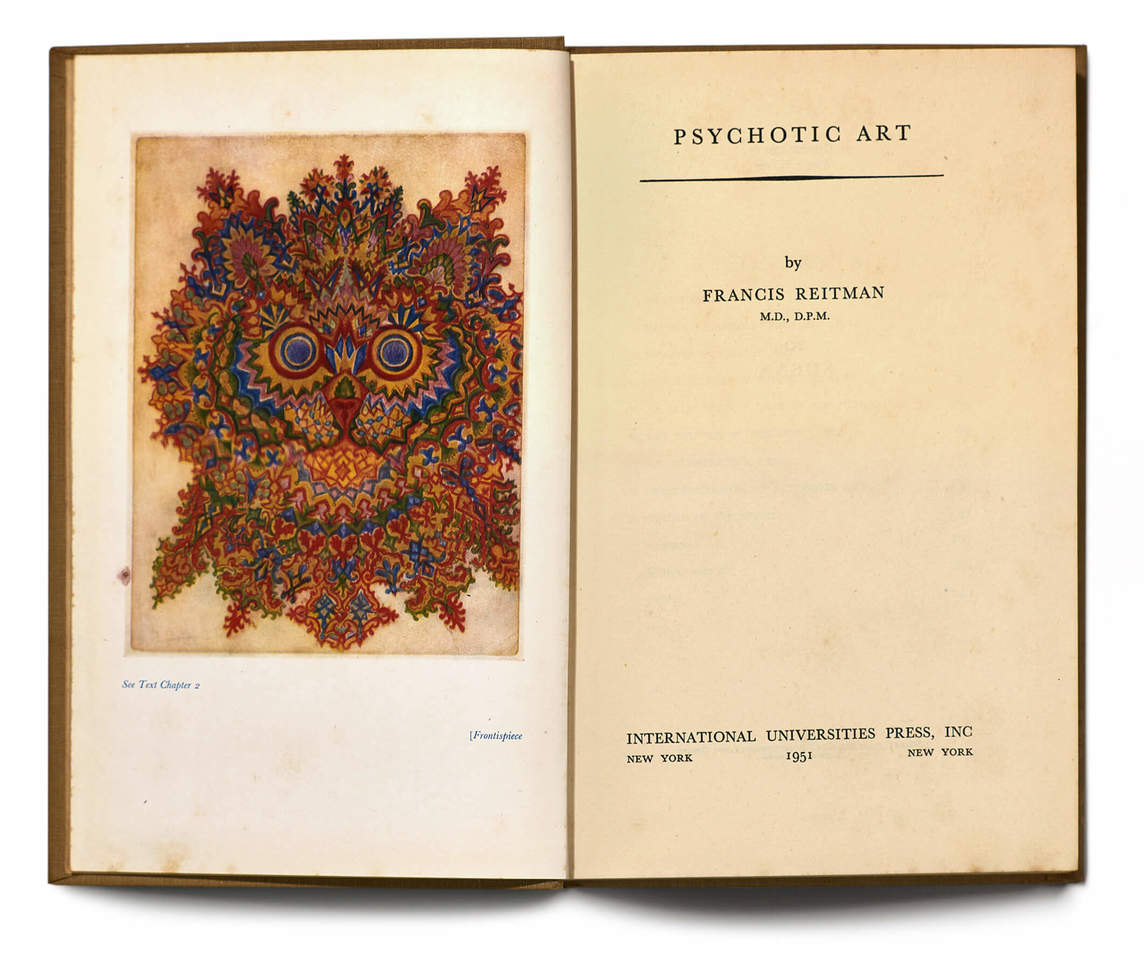

The first institution that Kurelek entered in 1952 was Maudsley Hospital in South London. Opened in 1907, with a focus on research and teaching, Maudsley’s role was to provide diagnosis and treatment for early onset mental illness. Dr. Francis Reitman was one of the professionals there exploring the potential effects of artmaking on mental illness. Although Kurelek never received direct treatment from Reitman, he certainly would have had access to the psychiatrist’s 1950 book Psychotic Art, which discusses how artmaking was being used as a form of treatment.

Kurelek also encountered psychiatrist Dr. Bruno Cormier at Maudsley. A French-Canadian, Cormier was sympathetic to Surrealism and was a signatory to the Automatistes’ 1948 Refus global manifesto. Though Cormier encouraged the artist to “relieve himself of aggressive feelings by painting them out,” Kurelek found the doctor “distant and ineffectual.”

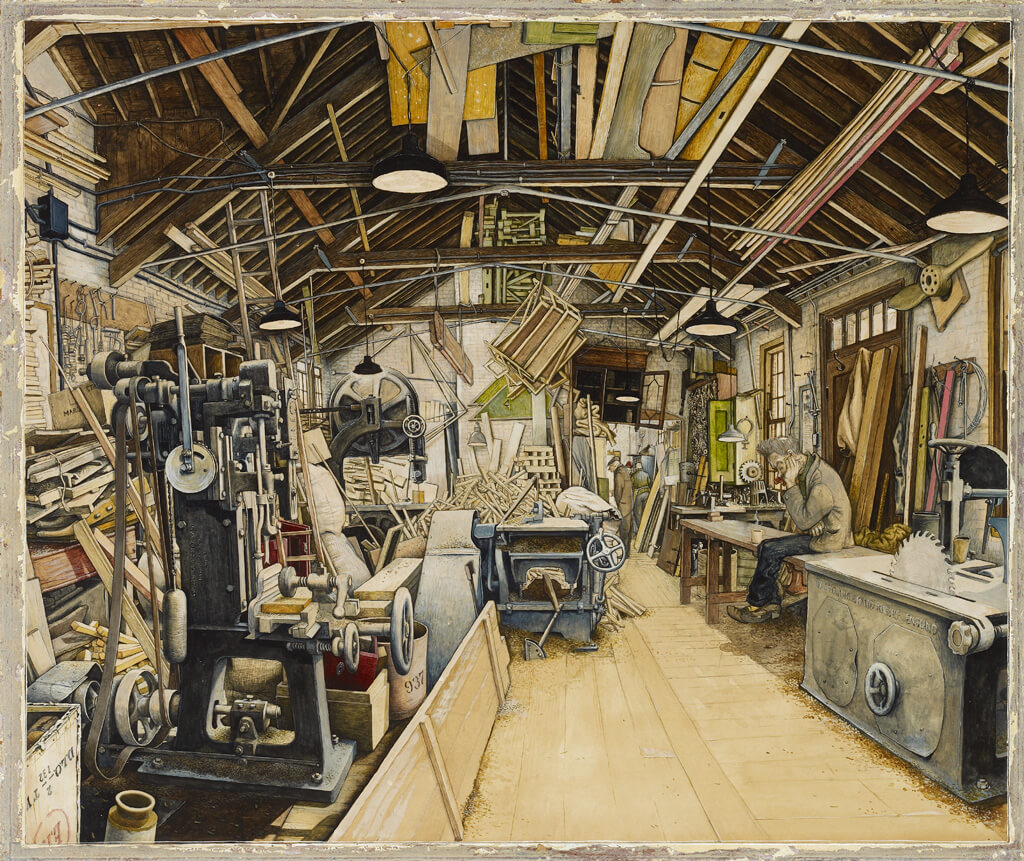

Kurelek painted feverishly at Maudsley, creating such memorable works as Tramlines, 1952, Farm Children’s Games in Western Canada, 1952, and The Maze, 1953, but it was not until he was transferred to Netherne Hospital in Surrey that he experienced a structured form of art therapy. During the 1950s the facility pioneered “the development of effective and humane treatments, including recreational activities for the mentally ill.” He depicted the extensive art facilities in Netherne Hospital Workshop, 1954.

Edward Adamson (1911–1996), Netherne’s art therapist since 1946, described Kurelek as “extremely withdrawn,” virtually silent, and unable to interact with other patients. Adamson did not offer technical instruction to Kurelek or the other patients. But he ensured Kurelek had his own studio, a small room previously used as a linen closet, and sought to impart art’s therapeutic benefits by maintaining “a positive and safe environment” where patients were “free of fear of criticism.”

A precise understanding of Kurelek’s mental condition and diagnoses at Maudsley and Netherne remains unknown. Accordingly, how we assess his claimed recovery in the late 1950s, its extent and permanence, is mere speculation, as his medical records are inaccessible to the public until 2029. Nonetheless, correspondence between the artist and the psychiatric professionals who provided treatment is accessible. Dr. Morris Carstairs, the senior registrar at Maudsley during Kurelek’s stay, offers a glimpse of Kurelek’s mental state in one letter: “[Y]ou would not want to claim that you had been psychotic, because you never were; but you could say that you have had times of severe emotional stress.”

Kurelek and His Contemporaries

Kurelek regarded his art as existing outside the contemporary art world. Though many artists, including Kurelek’s Toronto peers at Isaacs Gallery, had long been embracing non-traditional and secular forms of creative expression, Kurelek resolutely declared his affinity for the medieval ideal of the artist-as-craftsman. He unapologetically aligned his didactic “message” paintings, such as Dinnertime on the Prairies, 1963, with the religious and genre art of the Northern Renaissance .

However, the reality of Kurelek’s place within the Toronto art scene, and his relationship to art movements nationally, is more complicated than either the artist or his detractors admit. During the 1960s and 1970s, Isaacs Gallery featured art that included a diverse range of styles, media, and subjects. Whereas painters like Gordon Rayner (1935–2010) and William Ronald (1926–1998) were devoted to lyrical abstraction, artists such as Michael Snow (b. 1928), Les Levine (b. 1935), Greg Curnoe (1936–1992), and Joyce Wieland (1930–1998) engaged several kinds of media, producing conceptual works that drew from Dada.

Moreover, Kurelek’s realism, though distinctive for its practised lack of refinement, was not unusual. Toronto artists had an enduring realist tradition that lasted well into the postwar era. The social realism of the 1930s American Scene movement, whose artists emphasized the representation of contemporary rural and urban life, was popular in the city when Kurelek studied briefly at the Ontario College of Art in 1949–50. Kurelek’s former instructors Frederick Hagan (1918–2003) and Eric Freifeld (1919–1984), who were also deeply influenced by the older traditions of the Northern Renaissance, represent significant figurative realists working in this mode through the 1940s and 1950s. In the 1960s Jack Chambers (1931–1978), also a Roman Catholic convert, made films and honed photorealistic canvases of family life and the flat, semi-urban landscape of Southwestern Ontario. The works of Christiane Pflug (1936–1972) and Mark Prent (b. 1947) show deep familiarity with the German realist art movement of the 1920s New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit), a movement inspired in part by the same Northern Renaissance artists whom Kurelek celebrated, Pieter Bruegel (1525–1569) and Hieronymus Bosch.

Outside of Toronto, artists were adopting various modes of realism in the decades leading up to and during Kurelek’s two-decade career. Quebec’s Jean Paul Lemieux (1904–1990) practised a painterly realism that, like Kurelek’s, presented lonely figures in desolate, expansive landscapes. In the west, Ernest Lindner (1897–1988) created meticulously crafted paintings of stumps, moss, and fallen trees, emphasizing the natural cycle of rot and regrowth. In the Maritimes, Alex Colville (1920–2013) represented the bottled psychological anxiety of the postwar era, and his realism conveys, as do many of Kurelek tableaus, a latent tension and even violence through otherwise tranquil domestic scenes.

Kurelek’s realism and art historical debt to the Northern Renaissance do not completely distinguish the artist’s work from either his older or younger contemporaries. Despite their sometimes violent overtone, many of his more didactic paintings resonate with the same Cold War anxieties that haunted his peers and the public. Nonetheless, Kurelek’s work remains unmistakable. In its unexpected combinations of realism, memory, and message, a painting such as In the Autumn of Life, 1964, testifies to one of the most unified expressions of belief in action among twentieth-century Canadian artists.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements