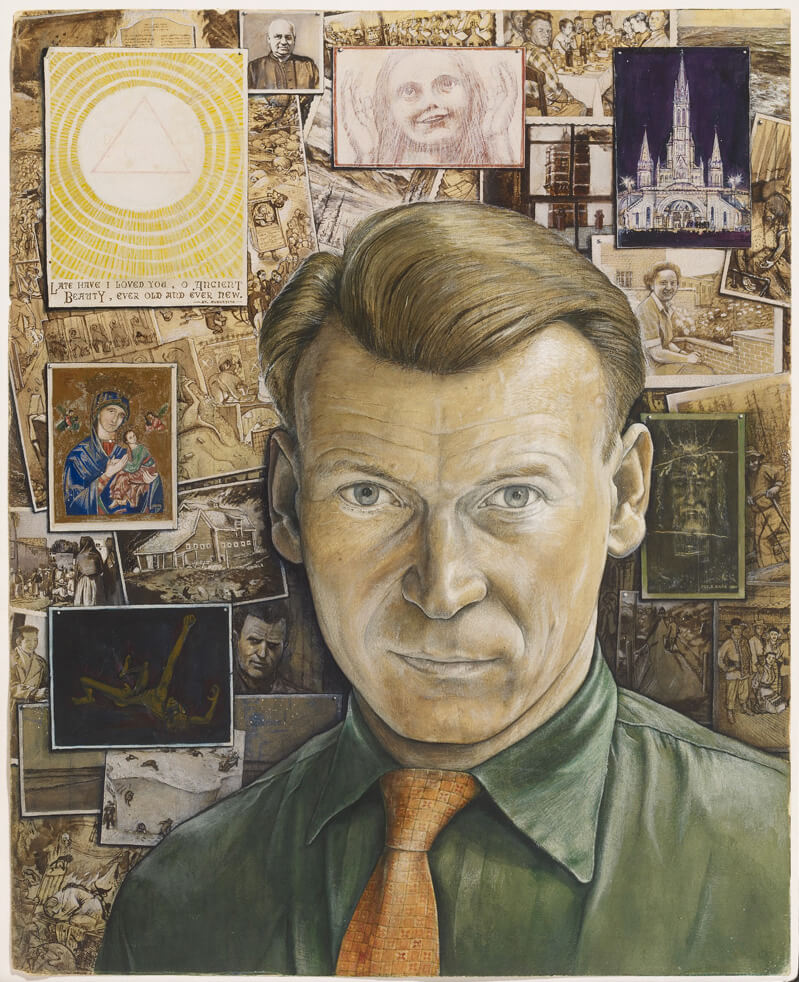

Self-Portrait 1957

William Kurelek, Self-Portrait, 1957

Watercolour, gouache, and ink on paper, 47.5 x 38 cm

The Thomson Collection, Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

This is the first significant work Kurelek painted after formally converting to Roman Catholicism. It was completed amid a flurry of activity. F.A. Pollak Ltd. in London, where Kurelek was employed, had closed over August for its customary summer respite. Kurelek used the time to paint, and he wrote a hundred pages of his autobiography, Someone With Me (1973, 1980). He also spent a week in Ireland in the company of Father Thomas Lynch, the Catholic priest who had coached him through his conversion.

The painting announces the artist’s new outlook through a thick overlay of imagery. Like his 1950 self-portrait, Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, this work imparts the story of his life by staging multiple narratives. However, whereas the 1950 self-portrait highlights the artist’s mastery of visual depth, the 1957 version showcases Kurelek’s immense skill at trompe l’oeil. Squared with the picture plane, Kurelek’s face, noticeably older and wiser, confronts and looks beyond the viewer. Kurelek’s body language and expression do not invite us to enter his inner world but ask us to bear witness to all he has overcome.

The personal overlaps the universal in an impenetrable wall of images that litter the shallow background. These images range from a reproduction of Kurelek’s Behold Man Without God, 1955, to a postcard containing an excerpt from St. Augustine’s Confessions. A drawing of a damned soul is mingled with photographs of Father Lynch, Kurelek’s father, and Margaret Smith, Kurelek’s occupational therapist at Maudsley. Images of Christ’s face on the Shroud of Turin, the Rosary Basilica, and St. Bernadette Soubirous confirm Kurelek’s earliest Catholic pilgrimages to Lourdes in 1956 and later in 1958.

More subdued in colour than the first self-portrait, the 1957 painting is also intended to be read as a statement of selfless humility and a pictorial vow against his earlier foray into the dark fantasies as characterized by The Maze, 1953, and Behold Man Without God, 1955. Beginning in the 1960s, Kurelek’s imagery would oscillate between that which celebrated the beauty of creation and those that relentlessly mined images of apocalyptic horror.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements