The art of William Kurelek (1927–1977) navigated the unsentimental reality of Depression-era farm life and plumbed the sources of the artist’s debilitating mental suffering. By the time of his death, he was one of the most commercially successful artists in Canada. Forty years after Kurelek’s premature death, his paintings remain coveted by collectors. They represent an unconventional, unsettling, and controversial record of global anxiety in the twentieth century. Like no other artist, Kurelek twins the nostalgic and apocalyptic, his oeuvre a simultaneous vision of Eden and Hell.

Fathers and Sons

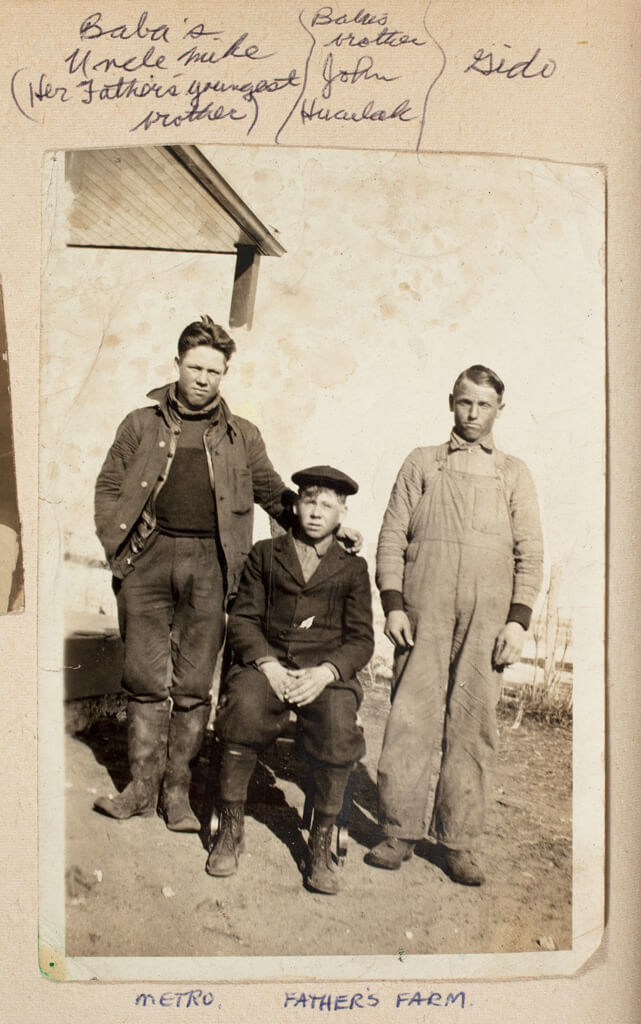

William Kurelek was born on a grain farm north of Willingdon, Alberta, to Mary (née Huculak) and Dmytro Kurelek in 1927. Mary’s parents had arrived in the region east of Edmonton around the turn of the century, in the first wave of Ukrainian immigration to Canada. These farming families, from what is known today as the Western Ukraine, transformed Canada’s harsh western prairie into a flourishing agricultural region and created an important market for the eastern manufacturing industry. The Huculaks established a homestead near Whitford Lake, then part of the Northwest Territories, in a larger Ukrainian settlement.

Dmytro arrived in Canada in 1923 with the second major wave of Ukrainian immigration. The families of Dmytro and Mary originated in the village of Borivtsi and the surrounding region of Bukovyna. The Huculaks sponsored Dmytro’s voyage to Canada and put him to work on their farm when he arrived. Dmytro married Mary in 1925. Two years later, on March 3 William was born and then baptized at St. Mary’s Russo-Greek Orthodox Church in Shandro. In 1934 the family abandoned Alberta for Manitoba suddenly and settled on a farm near the town of Stonewall, forty kilometres north of Winnipeg. Dropping grain prices that accompanied the Great Depression likely precipitated the move, as well as a fire that destroyed their house in the early 1930s. When the family’s wheat farming in Manitoba produced meagre results, Dmytro turned to raising dairy cattle.

The eldest of seven children, William spoke little English and was a cultural outsider to the community’s dominant Anglo-Protestant heritage, as was the case for his siblings closest in age, John and Winnie. The move to Manitoba coincided with the commencement of Kurelek’s formal education. He attended the one-room Victoria Public School, a mile’s walk from the family farm. A timid child, Kurelek’s formative years were deeply affected by the contests of the schoolyard, trials he vividly captured in later paintings such as King of the Castle, 1958–59. Kurelek floundered as a youth. Anxious, withdrawn, and prone to horrifying “hallucinations,” he developed a reputation among the family as physically inept, an impractical “dreamer.” Mental anguish and a fraught relationship with his parents, especially his father, defined Kurelek’s journey into adulthood.

Dmytro’s values and attitudes had been shaped by the brutality of the First World War and the struggles of subsistence farming. In the hardscrabble 1930s, Dmytro’s demand for practical solutions, mechanical proficiency, and physical stamina from his children, especially his eldest, was unwavering. Although his brother John flourished under paternal expectations, Kurelek mastered few of the virtues his father valued and he bore the brunt of Dmytro’s impatience; the patriarch’s exasperation only grew as the agricultural economy worsened through the decade. Consequently, Kurelek sought other ways of earning his father’s respect, chiefly through academic achievement: “It was obvious to me that, except for my good standing at school, I was in no way fulfilling his concept of what a son should be.”

Despite the hardships of his childhood, by grade one Kurelek discovered his talent for drawing. He covered his bedroom walls with drawings of “priests and angels, nurses, snakes, and tigers,” images culled from “radio melodrama, comics, Westerns, Jehovah’s Witnesses literature, dreams and hallucinations,” to the confounded disapproval of his parents. Conversely, Kurelek’s classmates praised his drawing skills and the often lurid and violent visual stories they told.

Culture and Community

In 1943 Kurelek and his brother John were sent to Winnipeg to attend Isaac Newton High School. For the first two years in the city, they lived in boarding houses. When Kurelek entered grade eleven, Dmytro purchased a house on Burrows Avenue for his three eldest children while they pursued their educations. Winnipeg was among the most cosmopolitan cities in the country, with a large population of Eastern Europeans and nearly forty thousand Ukrainians, who made it the “pulsating centre” of their culture in Canada. Ukrainian war veterans, labourers, entrepreneurs, and professionals, all adhered to a diverse range of political and religious outlooks. Kurelek found himself immersed in a vibrant and literate community that published newspapers, established language and heritage courses, and founded educational, religious, and cultural organizations.

Kurelek attended Ukrainian cultural classes at St. Mary the Protectress, the looming Ukrainian Orthodox cathedral directly across the street from his north-end home. The classes were led by Father Peter Mayevsky, who, in addition to inspiring enthusiasm for “the history of Ukraine, of her natural richness, her cultural beauty,” became the first adult to encourage Kurelek’s artistic bent.

In 1946 Kurelek began attending the University of Manitoba, where he majored in Latin, English, and history. He also took classes in psychology and art history, but literature was his central interest. The writings of James Joyce, and specifically Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916), were to prove particularly significant for Kurelek’s budding creative streak. “That book,” he writes, “had a more profound influence on me than any other single volume in my three years of higher learning. … [It] convinced me to rebel finally and completely against my family and become what I’d always half-wanted to be—an artist.”

During this period many of the psycho-physical conditions that would shape his adult life manifested. Kurelek was wracked by physical exhaustion, insomnia, inexplicable eye pain, social anxiety, and feelings of general malaise, depression, and low self-esteem—what he later identified as “depersonalization.” For the most part, Kurelek’s symptoms remained professionally undiagnosed.

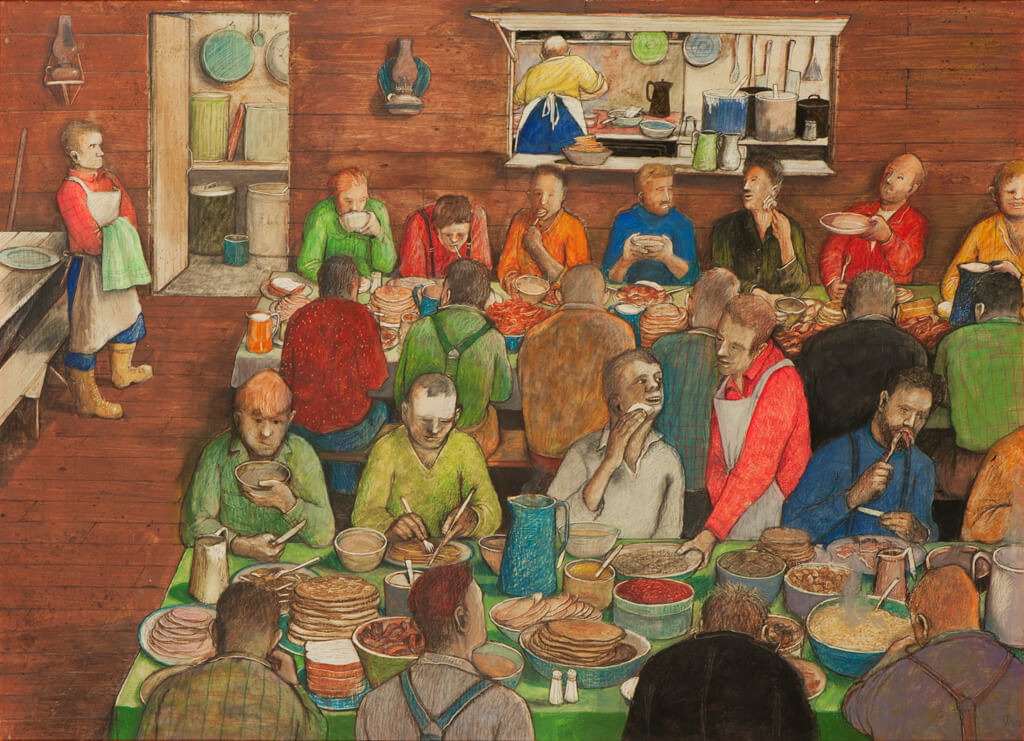

Summer employment took Kurelek east of Manitoba for the first time. He worked construction in Port Arthur (now Thunder Bay) and laboured at a Northern Ontario lumber camp, which he later depicted in works such as Lumber Camp Sauna, 1961, and Lumberjack’s Breakfast, 1973. Though these experiences buttressed Kurelek’s confidence, his emotional and mental suffering continued. Moreover, his relationship with his family, especially his father, did not improve.

Unsettled and Unsatisfied

In 1948 Kurelek’s family relocated from Stonewall to a farm in Vinemount near Hamilton, Ontario. In fall 1949, he began studying at the Ontario College of Art (OCA) under the pretence that it would facilitate a career in commercial advertising. His instructors included John Martin (1904–1965), Carl Schaefer (1903–1995), Frederick Hagan (1918–2003), and Eric Freifeld (1919–1984). Though Kurelek’s artistic interests were largely limited to figurative painting, they ranged from historical to contemporary images and were inspired by works from Northern Renaissance artists such as Pieter Bruegel (1525–1569) and Hieronymus Bosch (c. 1450–1516) to Mexican muralists Diego Rivera (1886–1957), José Orozco (1883–1949), and David Siqueiros (1896–1974).

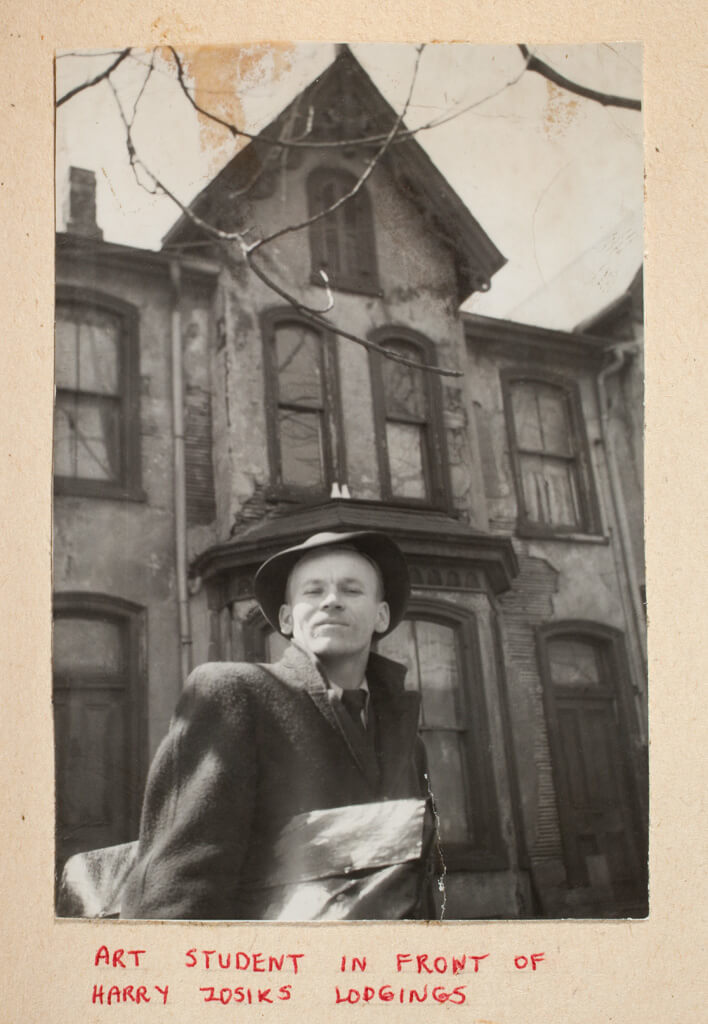

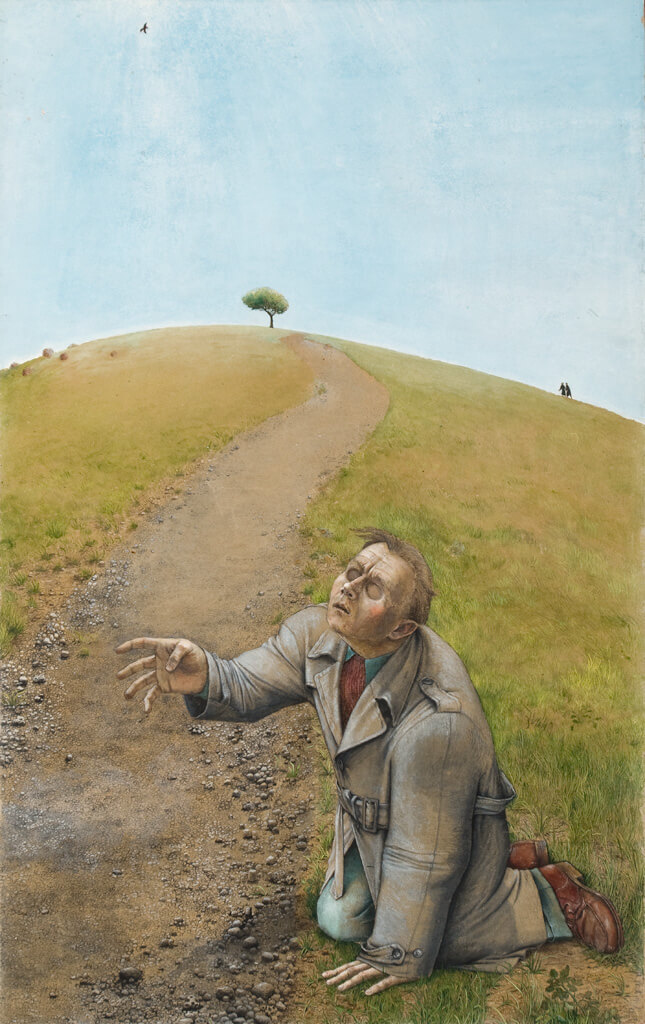

Although older than most of his fellow students, Kurelek made friends among classmates who included Graham Coughtry (1931–1999) and Rosemary Kilbourn (b. 1931). Several of his closest colleagues were committed socialists, and through them Kurelek was introduced to peace activist James Endicott. Despite being immersed in a stimulating intellectual environment, Kurelek was dissatisfied with what he perceived as an overemphasis on grades and competition at the OCA. He resolved to study with Siqueiros at San Miguel de Allende, Mexico. To pay for the trip, he spent the summer and fall of 1950 working odd jobs in Edmonton, temporarily living with an uncle before renting his own lodgings. At this time Kurelek painted his first masterpiece, The Romantic, a Joycean self-portrait he subsequently retitled Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, 1950.

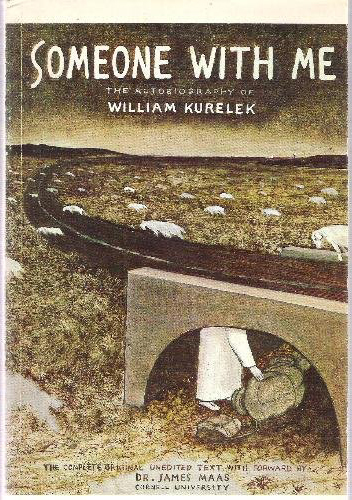

In fall 1950, Kurelek hitchhiked to Mexico. On his way, in the Arizona desert he had his first mystical experience, a dream in which after falling asleep beneath a bridge, he envisioned a figure in a white robe who urged him to “get up” and “look after the sheep, or you will freeze to death.” He pursued the sheep only to see them melt into mist and the robed figure “somehow blended into me and was gone.” Later Kurelek described the dream in his autobiography, Someone With Me (1973, 1980) and used it as inspiration for the cover art of the first edition.

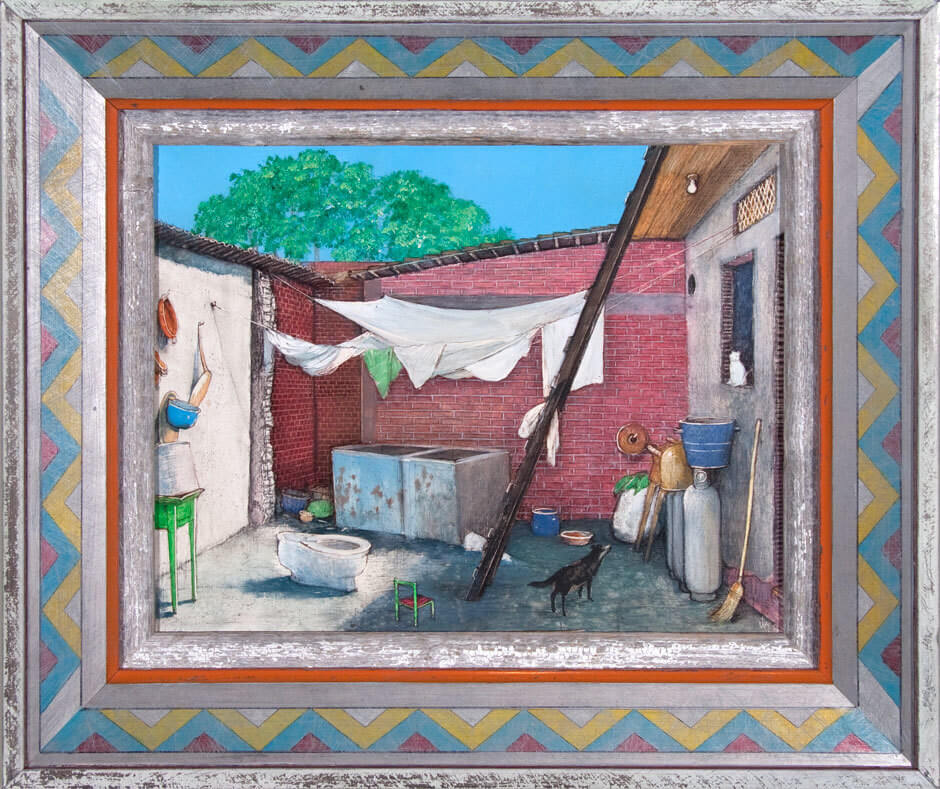

Kurelek’s wish to study “under a master painter” was thwarted because he arrived at San Miguel de Allende after Siqueiros’s sudden departure from the school. American expatriate artist Sterling Dickinson (1909–1998) then oversaw the establishment of a more formal Instituto Allende. Kurelek acknowledged that his time in Mexico proved “a great growing-up experience.” It broadened his artistic awareness and attuned him to social issues, such as the developing world’s grinding poverty, that would inform his mature beliefs system. A Poor Mexican Courtyard, 1976, suggests the lasting influence of his experiences.

Kurelek returned to Canada in spring 1951. However, he did not stay home for long. His “overriding yearning” was for professional diagnosis and help with what he called his mounting “depression and depersonalization” outside of the Canadian medical profession, an establishment Kurelek had come to regard as inept and money-driven. Although it is not clear whether Kurelek was aware of the growing interest in art therapy among British physicians, it is clear that he had contacted Maudsley, a London psychiatric hospital, before leaving Canada. After making the money for his passage to England by working as a lumberjack in Northern Ontario and Quebec throughout the summer and fall of 1951, Kurelek went to Montreal and boarded a cargo ship bound for England.

Crisis and Conversion

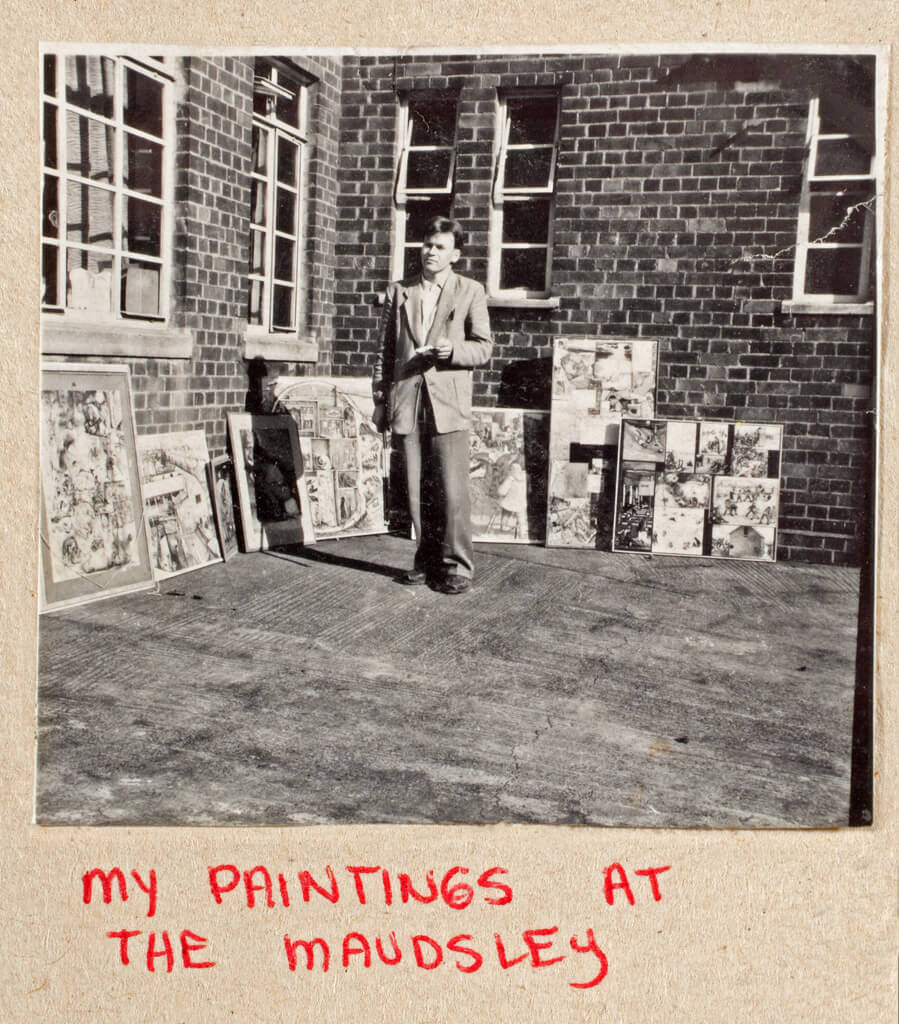

Kurelek arrived in England in spring 1952, and was formally admitted for psychiatric treatment at London’s Maudsley Hospital in late June. An internationally renowned institution, Maudsley treated many patients who were Second World War veterans suffering from what is now called post-traumatic stress disorder.

Professionals at Maudsley quickly recognized the gravity of Kurelek’s suffering, although the precise nature of his illness remains unknown. (The artist’s medical records detailing his specific diagnoses at Maudsley, and later at Netherne Hospital, remain inaccessible to the public until 2029.) The staff also acknowledged his artistic talent. As his recovery was believed to be dependent on his creative outlet, he was encouraged to continue painting. Kurelek demonstrated enough improvement that he was discharged from Maudsley in August. Soon after his release, he left England for a three-week tour of the major art collections in Belgium, the Netherlands, France, and Austria, where he viewed works by his Northern Renaissance paragons Bruegel, Bosch, and Jan van Eyck (1390–1441).

When he returned to London, Kurelek found postwar reconstruction work with the Transit Commission and continued visiting Maudsley as an outpatient throughout the winter of 1952–53. His condition continued to deteriorate and he was readmitted to Maudsley in May 1953. Assigned to the case in June, Dr. Morris Carstairs encouraged Kurelek to paint from memory, no matter how painful. Works such as The Maze, 1953, and I Spit on Life, c. 1953–54, illustrate how grim his outlook had become.

In these darkest hours Kurelek befriended Margaret Smith, an occupational therapist and a devout Roman Catholic. Empathetic to Kurelek’s plight, Smith also shared his love for English literature and poetry. Their time together at Maudsley was brief, but their platonic companionship was extremely significant for Kurelek. They continued to correspond after he returned to Canada. Years later, in 1975, Kurelek mailed Smith a copy of his book The Passion of Christ According to St. Matthew, in which he inscribed: “With my heartfelt thanks for making this all possible.”

In late 1953 Kurelek was transferred to Netherne Hospital in Surrey, an institution at the cutting edge of the art therapy movement in England. Netherne’s program was led by Edward Adamson, an artist who, along with the hospital’s physician superintendent, Dr. R.K. Freudenberg, “held that there was significant therapeutic benefit to patients if they could create in a positive and safe environment.”

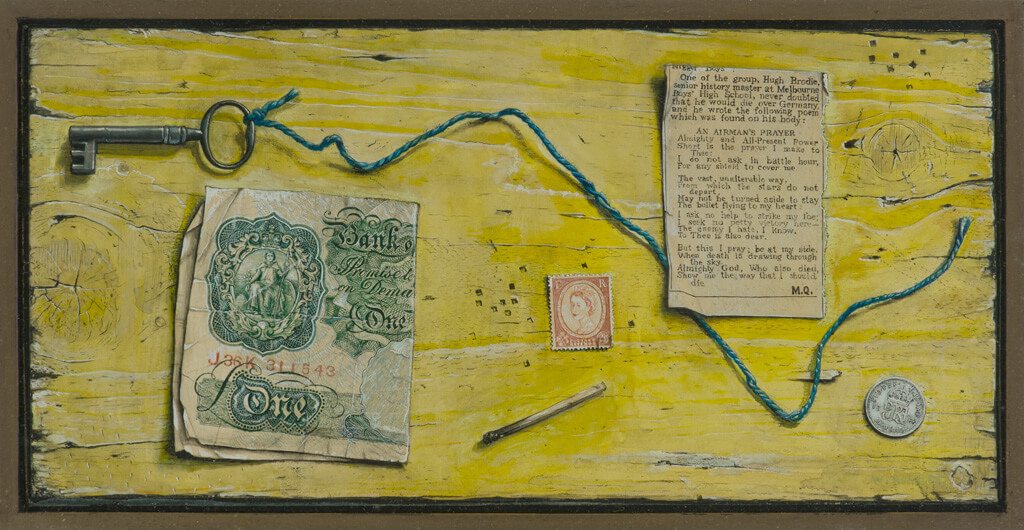

Kurelek received psychiatric treatment and made art, but his state worsened. In August 1954, he overdosed on sleeping pills and cut his face and arms in what he later described as a “half-measure” attempt at suicide. He willingly submitted himself to a dozen rounds of electroconvulsive therapy over three months, and his condition began to improve. Adamson encouraged Kurelek to break from his introspective tendencies and concentrate on the objective study of simple objects. During this time he executed several highly accomplished trompe l’oeil paintings of stamps, coins, and fabric fragments. Several of these paintings, including The Airman’s Prayer, c. 1959, were displayed at Royal Academy Summer Exhibitions.

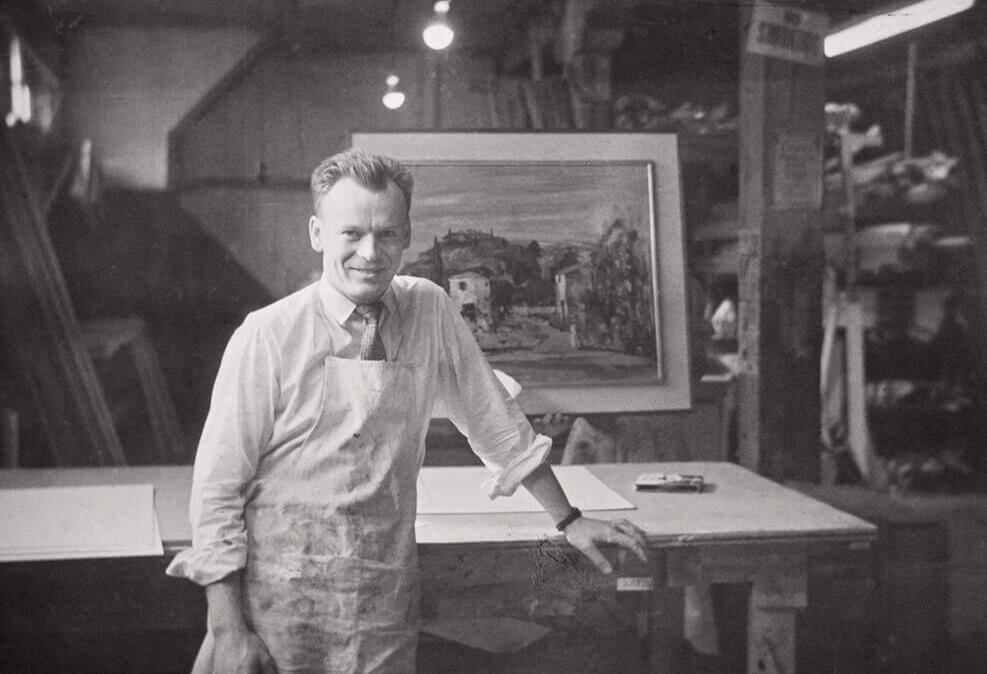

By January 1955 Kurelek was discharged from Netherne and he returned to London, where his luck began to turn. In late 1956 he found work at F.A. Pollak Ltd., one of the city’s most renowned art-framing and frame-restoration studios. He eventually became a master finisher. Kurelek also took classes in framing, cabinet making, and book design at the Hammersmith School of Building and Arts and Crafts.

An avowed atheist since university, by 1954 Kurelek’s mental illness had driven him into an existential crisis that spurred him to reconsider the existence of God. In his autobiography, Kurelek says his friend Margaret Smith largely precipitated his spiritual renewal. His 1955 watercolour Lord That I May See gives tangible witness to the spiritual questions he was grappling with. He began taking Catholic correspondence courses, joined the Guild of Catholic Artists and Craftsmen, and received instruction from a number of clergy, including the theologian Edward Holloway.

Kurelek made his first pilgrimage to Lourdes in France in March 1956 (he revisited the site in 1958). He returned to Canada over the summer to attempt reconciliation with his family, specifically with his father, a gesture that bore mixed fruit. Although the family welcomed him, Kurelek’s newfound religious commitments and his zealousness confounded them. In February 1957, several months after returning to England, Kurelek formally entered the Roman Catholic Church.

He remained in England for more than a year, working at Pollak and saving money, which allowed him to travel through Europe to the Middle East for nearly ten months beginning in the summer of 1958, a trip intimately connected to his art practice and new faith. Travelling via Central and Eastern Europe through Turkey and Syria, Kurelek made his way to Jordan and Israel for a more sustained visit. He hoped to gain a “working knowledge of the area in which Christ had lived and died.” He spent much of his time in the region drawing and taking photographs that he used as reference for the Passion series he completed between 1960 and 1963.

Reborn in Toronto

By June 1959 Kurelek had returned to Canada permanently, and for a brief period he lived with his parents on their farm in Vinemount, Ontario. Eventually he moved to a boarding house on Huron Street in Toronto, where he continued to paint. He also began pursuing teaching certification, but his psychological history prompted the Ontario College of Education to deem him unfit for the work, a rejection that must have felt particularly bitter following his years of treatment in England.

Kurelek’s situation showed signs of hope in fall 1959. He met Avrom Isaacs, the man who launched Kurelek’s career and provided him with stable employment. The owner of one of Toronto’s first postwar contemporary art galleries, Isaacs was introduced to Kurelek and his art through a mutual friend of his wife. Greatly impressed, he offered Kurelek a job in the gallery’s frame shop and his first solo exhibition at Isaacs Gallery in late March 1960.

In the 1960s Isaacs Gallery represented some of the country’s most avant-garde contemporary artists, including Michael Snow (b. 1928), Joyce Wieland (1930–1998), and Greg Curnoe (1936–1992). Kurelek felt himself to be, and was viewed by many, as the art world’s “odd man out.” His work was representational, narrative-driven, and often religious in a climate in which Toronto artists, galvanized by dominant New York Abstract Expressionists such as Jackson Pollock (1912–1956), faced off against a growing contingent of irreverent Neo-Dada artists inspired by Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968).

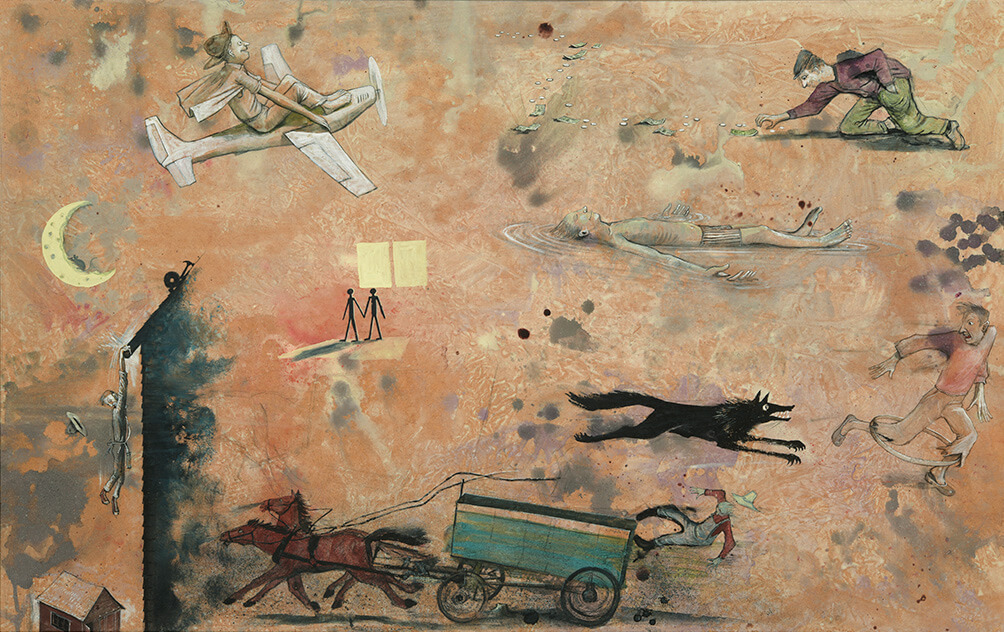

Nonetheless, Kurelek’s first solo show broke Isaacs’s previous exhibition attendance records. This exhibition, largely of work from his time in England, included trompe l’oeil paintings, Behold Man Without God, 1955, and his post-conversion Self-Portrait, 1957. Kurelek’s second exhibition, Memories of Farm and Bush Life, took place at Isaacs Gallery in 1962. Public response was even more positive as the works featured, such as Farm Boy’s Dreams, 1961, introduced audiences to what became another, immensely popular facet of Kurelek’s creative output: the nostalgic visual recollections of Kurelek’s youthful experiences in Alberta, Manitoba, Northern Ontario, and Quebec.

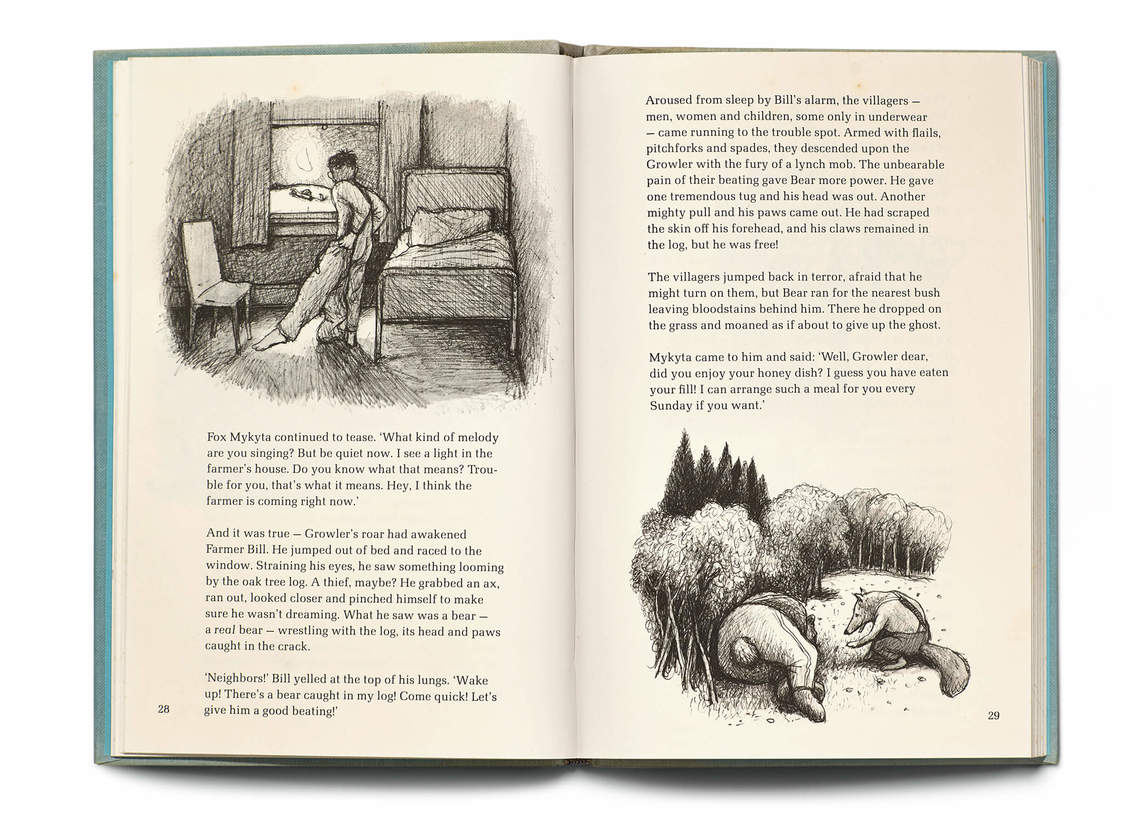

Kurelek continued to exhibit his work commercially, primarily at Isaacs Gallery but also at La Galerie Agnès Lefort in Montreal and Mira Godard Gallery in Toronto, among other venues across the country. Over the ensuing decade he had major exhibitions at several public institutions, including the Winnipeg Art Gallery (1966), Hart House at the University of Toronto (1969), Edmonton Art Gallery (1970), Burnaby Art Gallery (1973), and Art Gallery of Windsor (1974). During this period Kurelek illustrated a number of highly successful books, including W.O. Mitchell’s Who Has Seen the Wind (1976) and Ivan Franko and Bohdan Melnyk’s Fox Mykyta (1978), as well as two he wrote himself, A Prairie Boy’s Winter (1973) and A Prairie Boy’s Summer (1975).

Happy Canadian, Dark Prophet

Kurelek’s growing success emboldened him and helped him settle into his skin. By the early 1960s he had met Russian émigré Catherine de Hueck Doherty, the founder of the apostolic Roman Catholic training centre Madonna House located northeast of Toronto, who, like Kurelek, had been born into the Orthodox Church. Kurelek’s painting The Hope of the World, 1965, was in part inspired by Doherty’s efforts to “blend … Eastern and Western [Christian] spirituality” at Madonna House.

In 1962 Kurelek married Jean Andrews, whom he had met at Toronto’s Catholic Information Centre. By 1965 the artist’s first two children had been born and a third was expected. The family relocated from an apartment near High Park to Balsam Avenue, in the city’s Beaches area. Domestic stability did not spell the end of creative complexity, however. Throughout the 1960s and early 1970s Kurelek’s work became more polarizing.

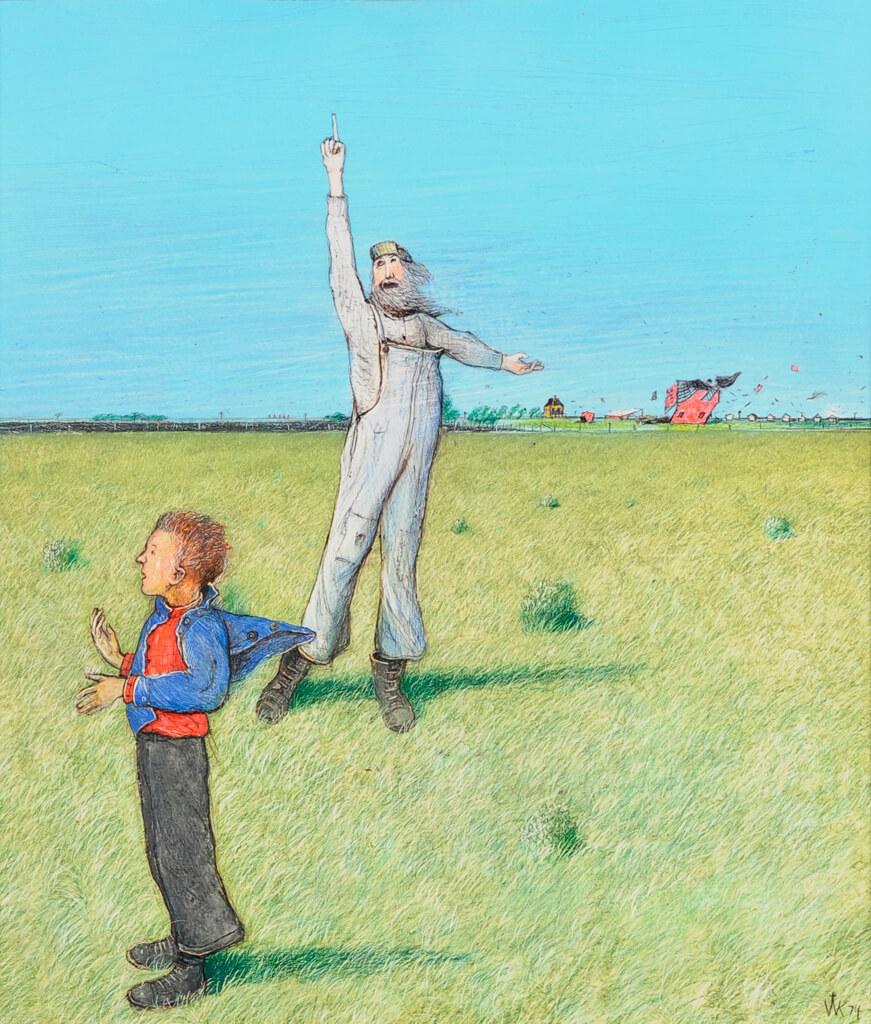

By the mid-1960s Kurelek was rekindling his love for his Canadian prairie birthplace. He was spurred to make recurring sketching trips throughout Western Canada and the Maritimes, Arctic, and Pacific Coast in subsequent years. This joyous, inspired nationalism emanates from The Painter, 1974, a late self-portrait in which Kurelek sets himself en plein air, in the red Volkswagen Beetle that served as transport, motel room, and painting studio during many of his sketching expeditions. These cross-country voyages witnessed the reintroduction of photography as an artistic aid, a medium Kurelek first integrated in his creative practice when travelling through the Middle East in 1959.

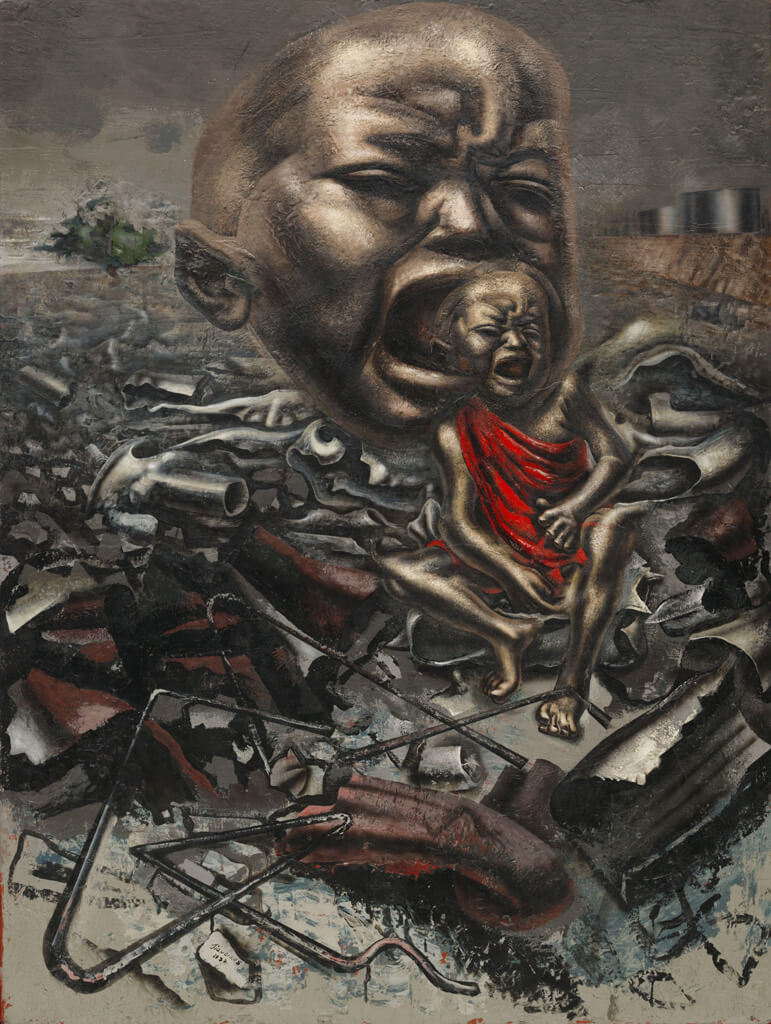

At the same time Kurelek produced exhibitions containing what critic Harry Malcolmson called “fire and brimstone” work, including Experiments in Didactic Art, 1963; Glory to Man in the Highest, 1966; The Burning Barn, 1969; and Last Days, 1971. These series gave voice to Kurelek’s personal exhortations against the political fallout of secular morality. The artist blamed the Cold War and environmental degradation on the amorality of secular and scientific humanism. Concurrently, the raw anxiety and apocalyptic foreboding that Kurelek’s imagery reveals were shared by a growing number of people, especially following the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962.

Kurelek’s apocalyptic anxiety led him to action. He began planning to construct a fallout shelter in the basement of his Balsam Avenue house. His scheme became public knowledge in 1967 and was met with resistance. Family and friends found his morbid pursuit of self-preservation distasteful and questioned whether it squared with the artist’s Christian ethics, while neighbours and City officials faulted the shelter’s structural technicalities. By the early 1970s Kurelek had retired his plans to transform his workspace into a bomb shelter; thus, the room continued to serve as his studio until his death.

Kurelek travelled to Ukraine for the first time in 1970. He briefly visited his family’s ancestral village of Borivtsi, despite being under close surveillance by Soviet authorities. The trip inspired the monumental The Ukrainian Pioneer, 1971, 1976. With the advent of multiculturalism, Kurelek’s interests expanded to include other language, ethnic, and religious groups in Canada. Before his death he completed series about the Inuit, as well as Jewish-, French-, Polish-, and Irish-Canadians.

Kurelek was admitted to Toronto’s St. Michael’s Hospital soon after returning from a second trip to Ukraine in fall 1977. He succumbed to cancer on November 3. A year earlier he was made a Member of the Order of Canada. Avrom Isaacs estimates Kurelek had produced “well over 2,000 paintings and drawings” at the time of his death.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements