The path of war art in Canada has mostly followed Western approaches, with the exception of older Indigenous art forms, which have been challenged by issues of survival and diverted because of a lengthy association with ethnography and ethnology. Europe’s long tradition of representational oil painting dominates, as do other established Western art forms such as sculpture, drawing, and printmaking. Film, photography, and video have come to the fore since the nineteenth century, and poster art, a critical propaganda tool during the First and Second World Wars, has since diminished in significance. Today, the ever-evolving realm of digital media is rapidly emerging as a key practice.

Painting

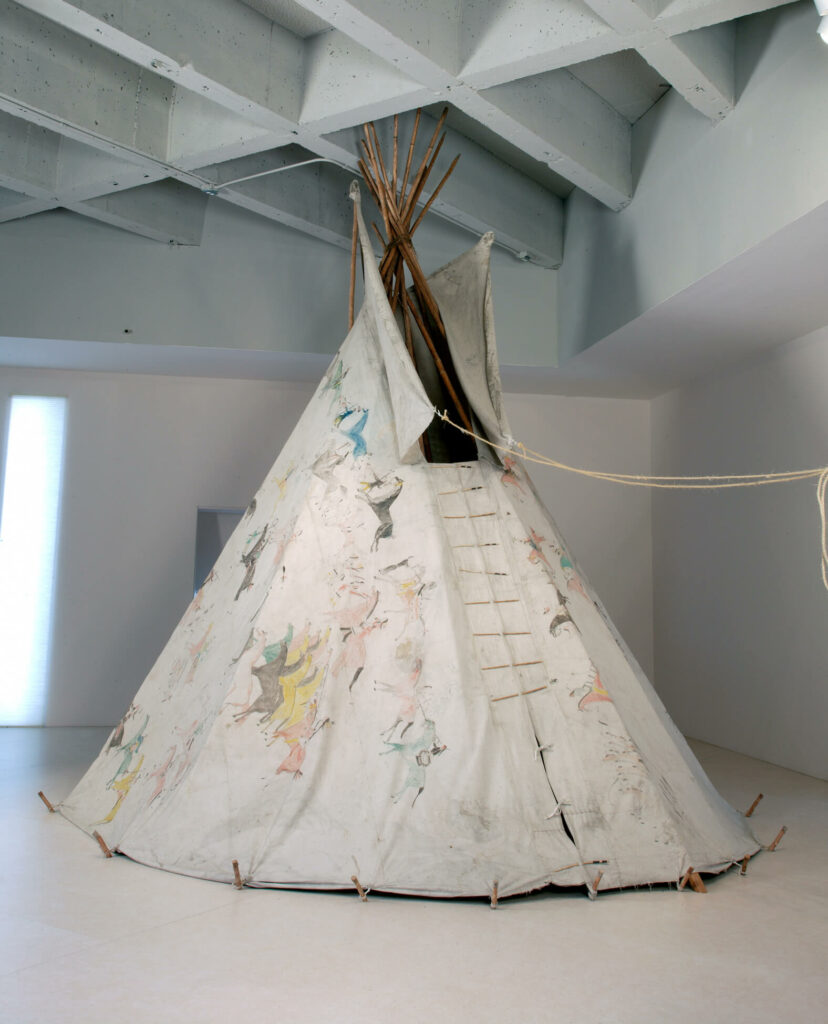

We know, from a number of surviving nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Plains war exploit robes, that Indigenous peoples in Canada painted war as part of their culture. Indeed, using mostly earth pigments, more than thirty tribes across the North American Great Plains painted not only on robes but also on shirts, tipi (tent) coverings, linings, and ledger books. Although many details have been lost, we do know that the pictographs that populate these painted items were closely connected to oral traditions and helped to describe and commemorate information about past military exploits. In their purpose, therefore, their role was hardly different from the artworks colonizers commissioned.

Canadian colonists considered painting in oil a superior skill, and history composition the most important genre. Not surprisingly, therefore, painting on canvas became the principal medium associated with the three Canadian official war art programs during the twentieth century—the Canadian War Memorials Fund (CWMF), the Canadian War Records, and the Canadian Armed Forces Civilian Artists Program. It was also dominant in military artwork by independent artists not associated with these programs.

The majority of the official artworks created during and immediately after the First World War were representational battle paintings and portraits, although some of the Canadian artists who had studied in Europe, such as A.Y. Jackson (1882–1974), Frederick Varley (1881–1969), and Arthur Lismer (1885–1969), were influenced by the modern styles of Impressionism, Expressionism, and even Cubism. For his painting A Copse, Evening, 1918, and in accordance with his academic training, Jackson first created a sketch of his composition annotated with notes indicating areas of colour. The final painting presents a mottled Impressionist sky completed with light, feathery strokes. Similarly, the relationship between Jackson’s study for Vimy Ridge from Souchez Valley, 1918, and the finished work reveals his approach.

Lismer’s Convoy in Bedford Basin, c.1919, also owes a significant debt to Impressionism in its plein-air approach and lively brushwork, although its subject—camouflaged vessels—is indebted in its “dazzle” design to Cubism. However, Varley’s For What?, 1918, imbued with pathos, reflects more late-nineteenth-century Expressionism and the gloomy landscape style of northern Europe, one he would have encountered as a student in Antwerp, Belgium.

Most of the First World War oversize canvases of Canadian subjects created for the CWMF are by British painters. The largest—a massive 3.7 by 12 metres—is by Welsh artist Augustus John (1878–1961). This figurative mural, entitled The Canadians Opposite Lens, 1918–60, remained unfinished at his death. The city of Lens was strategically important to Canadians during the war, but the mural, a hodgepodge of ruins, shattered trees, refugees, relaxing and wounded soldiers, and horses and wagons, conveys little of the conflict’s everyday horrors. His colleague Paul Nash (1889–1946), who also worked for the Canadian scheme and hugely influenced Jackson, created a very different impression in his dramatic, tragedy-infused warscape Void, 1918, now in the National Gallery of Canada.

During the Second World War, Canadian painters included those who were officially commissioned as well as independent artists. The works the official artists produced followed the technical guidelines stipulated by the war art program and were almost all in the range of 80 by 100 centimetres in size. These guidelines also specified the subjects they should paint—soldiers, equipment, training, and terrain, among others.

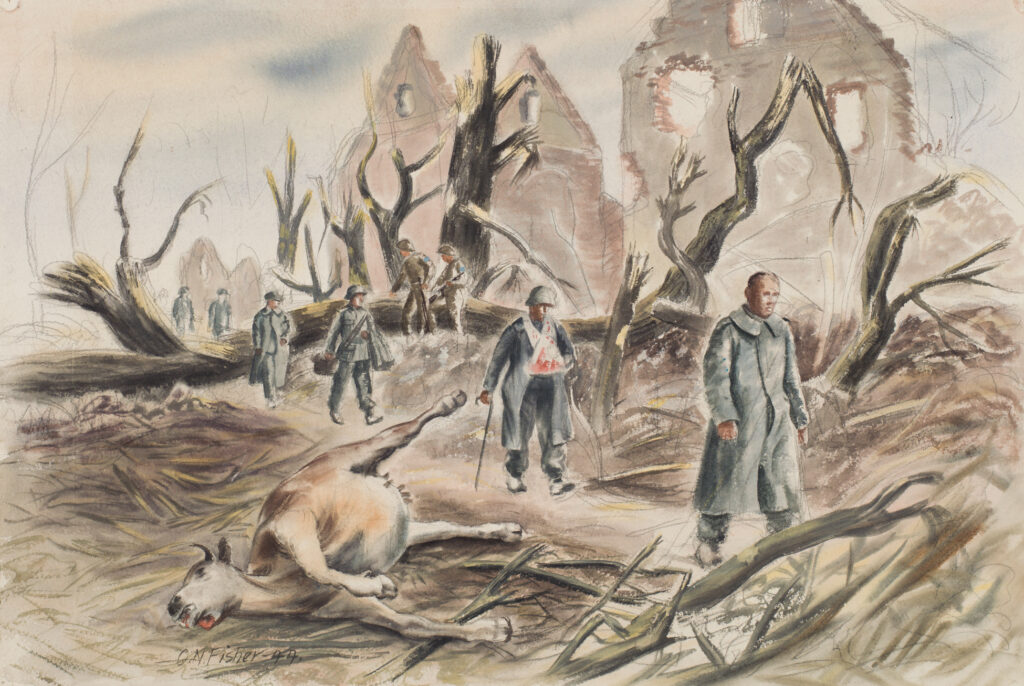

To ensure that the finished canvases were worthy of exhibition and collection, historical officers enforced a strict production process to ensure accuracy. The method began with on-the-spot sketching and, sometimes, photography. In preparation for the D-Day invasion on June 6, 1944, Orville Fisher (1911–1999), for example, innovatively strapped tiny waterproof pads of paper to his wrist. After racing up the beach from his landing craft, he made rapid sketches of the battle unfolding around him using perfectly dry materials. Sadly, these drawings have not survived. Later, the artist created larger watercolour paintings away from the battlefront. The time, date, location, event, and the names of the units depicted were carefully noted on the back.

The historical officers attached to the same units as the artists assessed their works on paper for accuracy and any breach of censorship before forwarding them to London, where the artists later completed a selected number in oil—for example, Fisher’s depictions of prisoners of war after the Battle of Falaise Pocket in the Battle of Normandy, 1944 (sketch), 1945 (painting). In 1946, back in Canada, twenty-three officially appointed artists worked in studios supplied by the government in Ottawa, including Alex Colville (1920–2013) on Bodies in a Grave, 1946, and Jack Nichols (1921–2009) on Drowning Sailor, 1946.

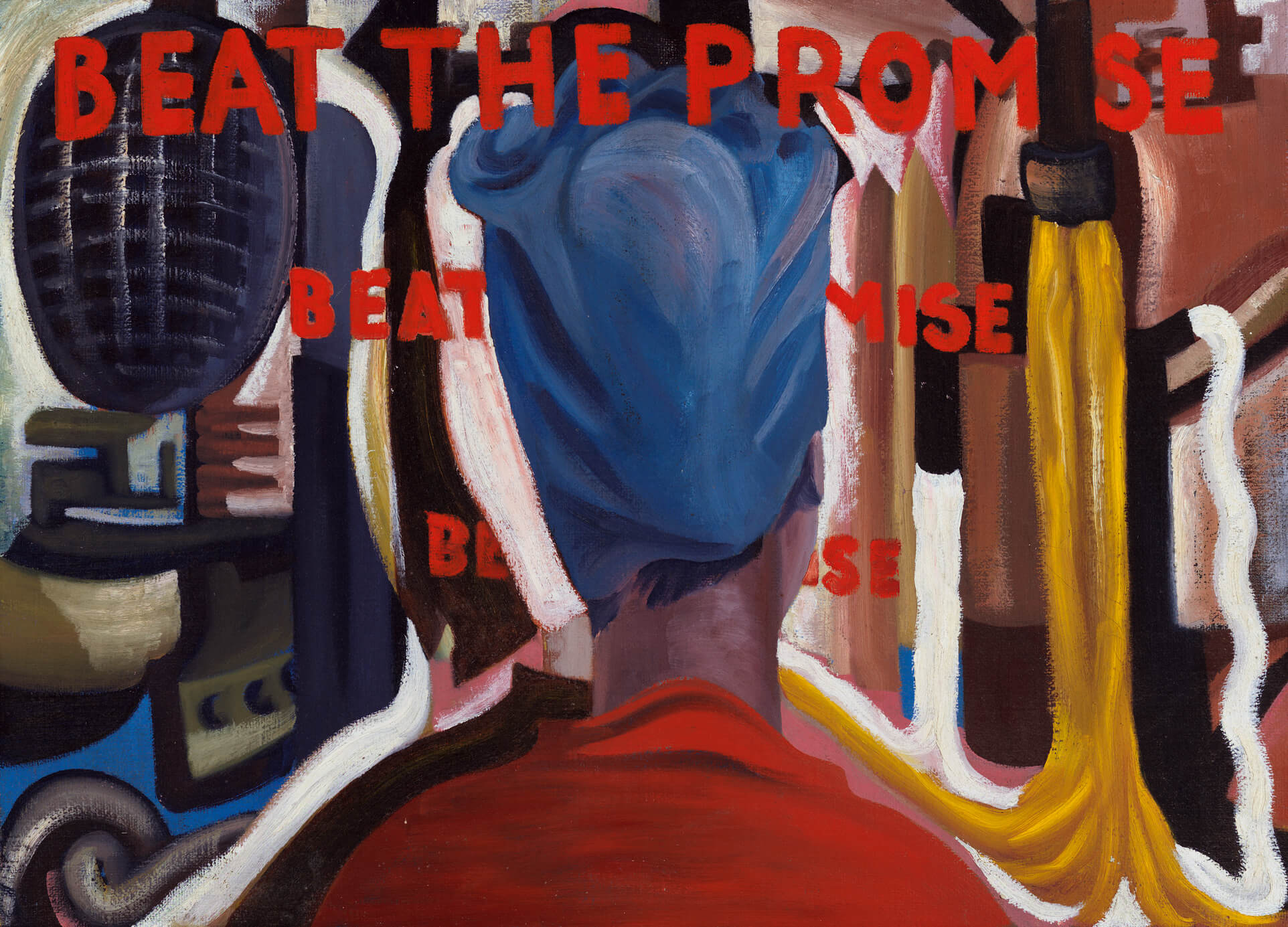

The paintings of Second World War unofficial civilian and soldier artists vary greatly because their work was not subject to official conditions. Beat the Promise, 1943, by modernist pioneer Lowrie Warrener (1900–1983) abstractly shows the back of a female industrial worker around whom the music and propaganda messages, or “muzak,” piped in to muffle the noise of the machines is depicted in words. The Soldier’s Wife, 1941, by Elizabeth Cann (1901–1976) poignantly captures the fear for a partner’s life shared by the spouses of serving military personnel. Airburst Ranging Observer, 1944, by Alan Collier (1911–1990) is a military self-portrait. He depicts himself with the tools he used as a member of a Royal Canadian Artillery survey team. On the tripod before him is a theodolite, a precision instrument for measuring angles to aid in mapping. The circle above his head shows what he can see through it.

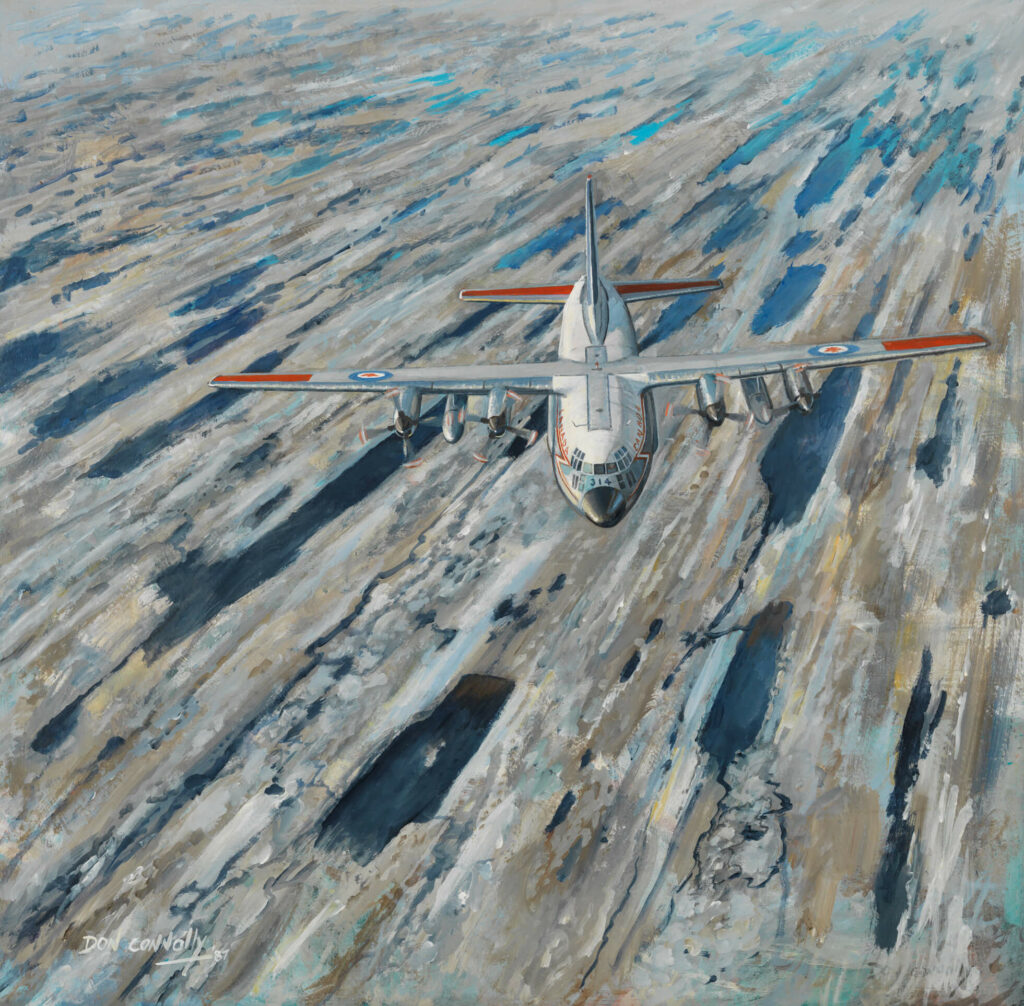

The participating artists in the post–Second World War Canadian Armed Forces Civilian Artists Program (CAFCAP) were, with a few exceptions, primarily painters. The documentary painting Paphos Gate, C-73 Observation Post, Cyprus, 1990, by Réal Gauthier (1933–2017) depicts one of the three narrow sixteenth-century Venetian stone gates or archways into Nicosia beside a newer road cut into the original city walls. Confirming its then role as an observation post, a white United Nations vehicle is parked beside the gate. Independent painting on military themes in that period is more likely to be Canada-based and is largely associated with organizations such as what is now known as the Canadian Aviation Artists’ Association—a typical example being Over the Back Forty, 1987, depicting an Arctic flight, by Don Connolly (b.1931).

Painting continues to be represented in the ongoing Canadian Forces Artists Program (CFAP), launched in 2001. Examples include the lyrical bird’s-eye view icescape Kaskawulsh III 60°44’N; 138°04’W, 2014, by Leslie Reid (b.1947); the atmospheric Ready State, 2013, by Scott Waters (b.1971), showing the darkened interior of a CC-177 Globemaster III military transport plane; and, independent of the program, the vivid What They Gave, 2006, by Gertrude Kearns (b.1950), a former CFAP artist. All three use paint very differently to create effects that range from the delicate and subtle in the case of Reid, to almost photographic smoothness in the work of Waters, to the dramatic and gestural in Kearns’s composition.

With no experience of Canada’s military art programs, Cree artist Kent Monkman (b.1965) has painted potent commentaries on the Indigenous experience of military colonialism, such as Miss Chief’s Wet Dream, 2018. The paints available to painters today are very different from those used by earlier artists, mainly because of environmental and health issues. Lead-based colours, for example, are now largely banned in the developed world, and the newer acrylic types do not require toxic thinners for cleaning brushes, knives, and palettes.

Sculpture

We know from surviving examples that Indigenous peoples in Canada were from time immemorial expert carvers in stone and wood. More often than not, however, in relation to war art, their skills were directed to the decoration of weaponry and related functional objects such as canoes, clubs, and paddles, many of which have not survived. Peace pipes also were carved in stone, as in the anonymous Haudenosaunee Turtle Calumet, 1600–50, in the Royal Ontario Museum’s collection.

While there are earlier colonial memorial sculptures, such as those associated with the South African War, 1899–1902, the First World War was a high point for sculpture in Canada. Almost every town and village across the country installed some kind of monument—which was usually, but not always, figurative. They were sites of memory and a place where future Remembrance Day services could take place. Although Canadian sculptors did well from commissions, at least half of the work was imported from Italy and other countries. The celebrated Romantic-style French sculptor Auguste Rodin (1840–1917), whose tragic yet resolute life-size figures in The Burghers of Calais, modelled 1884–95, encouraged a meaning-laden form of sculpture, influenced many Western war memorial sculptors in bronze and stone.

Grief, 1918, by Frances Loring (1887–1968), depicting a woman slumped over in sorrow, exemplifies this kind of emotional expression. Loring and her partner, Florence Wyle (1881–1968), received a major commission from the Canadian War Memorials Fund in 1918 to create fourteen bronze figures of workers on the home front.

Symbolism is explicit in Allegory of War, c.1912–17, a romantic plaster model of a band of soldiers protected by a winged figure above by Quebec sculptor Alfred Laliberté (1878–1953). It is present too in the fearsome bronze warrior 1914, c.1918, by Henri Hébert (1884–1950), caught as he plunges his sword into, presumably, another body. German-born sculptor Emanuel Hahn (1881–1957) drew on Moloch, the Old Testament god associated with childhood sacrifice, for his dramatic plaster model War the Despoiler, 1915, which depicts the monster devouring conflict’s young victims.

National identity with past valour is important in figurative commemorative military sculpture such as Dollard des Ormeaux, 1916, by Louis-Philippe Hébert (1850–1917) (Henri’s father), with its image of a historical French hero meant to encourage reluctant Quebec participation on the British side during the First World War. After the conflict, Robert Tait McKenzie (1867–1938) created war memorials as well as small, personal sculptures such as Captain Guy Drummond, after April 1915, and Wounded, 1921, that reflect movingly on the consequences of battle.

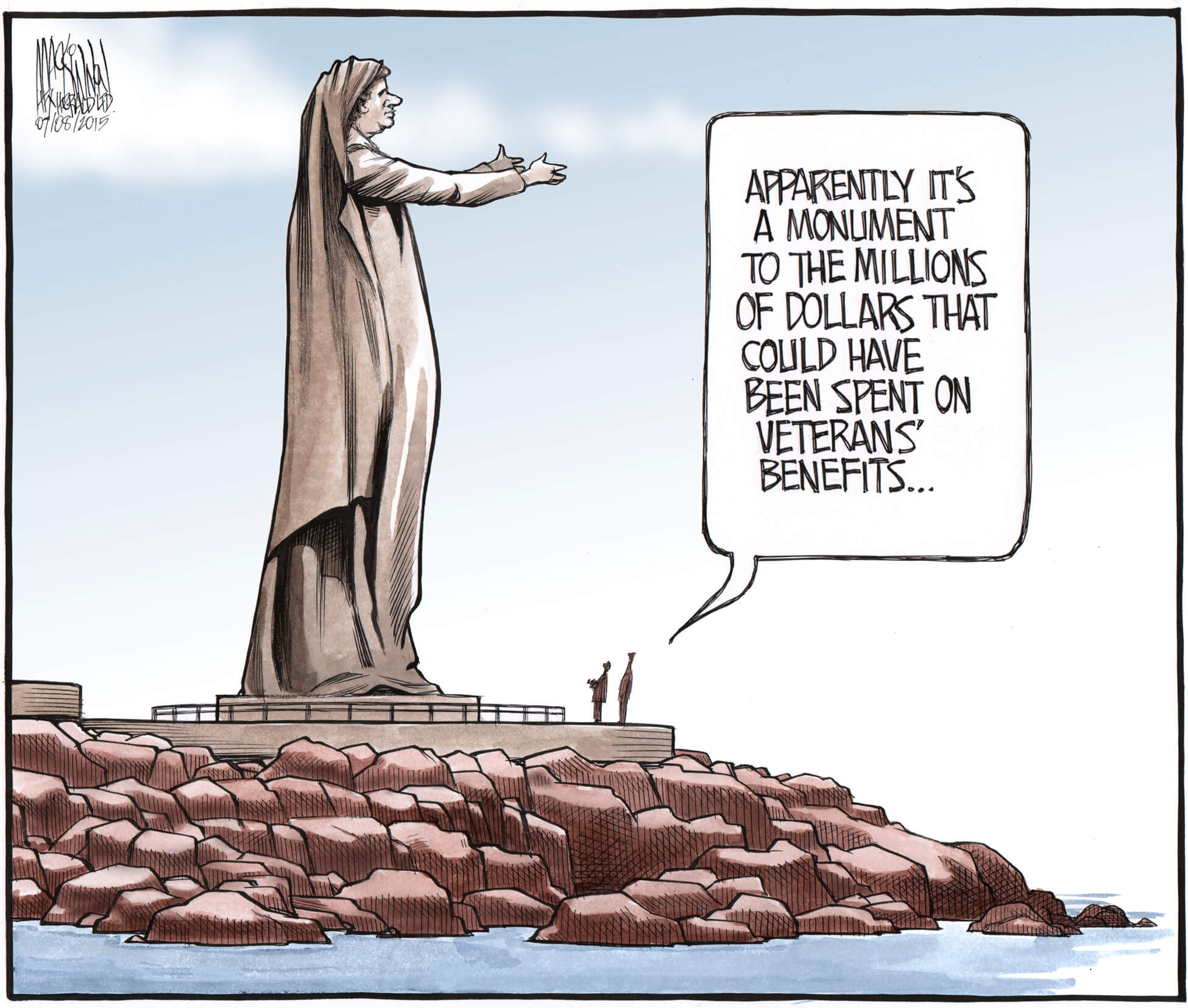

Canada’s best-known war sculptures are the twenty allegorical figures associated with the Canadian National Vimy Memorial, 1921–36, at Vimy Ridge, France, by Walter S. Allward (1874–1955). This figurative monument, which is infused with religious symbolism, helps make visible to viewers abstract concepts that are associated with war such as courage, sorrow, grief, endurance, fear, and pain. Allward hoped that visitors, as they viewed the central maternal figure of Canada Mourning Her Fallen Sons, would find comfort for their own personal loss in a shared appreciation of this powerful emblem of national grief. Canada “Bereft,” c.1921, is the original small-scale model for this figure. The iconic imagery of Canada mourning her dead later inspired, as this cartoon shows, a much-mocked design for a war memorial in Nova Scotia that was ultimately never built.

Many of the memorials, including the National War Memorial in Ottawa, 1926–32, were not completed until just before the outbreak of the Second World War. A mood of disillusionment set in at the conclusion of that conflict, and there were no new large commissions for sculpture-decorated edifices. Instead, dates and names were mostly added to existing monuments as required. One exception is the abstract Cénotaphe de Chicoutimi, 1958, by Armand Vaillancourt (b.1929), which commemorates the peace that followed both world wars. Another is the National Aboriginal Veterans Monument, 2001, by Cree sculptor Noel Lloyd Pinay (b.1955) of Saskatchewan’s Peepeekisis First Nation.

Sculpture is also largely absent from the postwar Canadian Armed Forces Civilian Artists Program, and it is rare in the Canadian Forces Artists Program (CFAP). The first sculptor to graduate from the CFAP scheme was François Béroud (b.1961), with his abstract stainless-steel HMCS Toronto, 2005. More recently, Maskull Lasserre (b.1978), who has participated twice in CFAP, has built up an impressive body of sculpted work on the theme of conflict. His weighty meditation on wartime security entitled Safe, 2013, is an actual safe that, inside, replicates the interior of a Light Armoured Vehicle, or LAV.

Prints and Drawings

The painting The Death of General Wolfe, 1770, by Benjamin West (1738–1820) provided the first widely circulated print of a painting with Canadian content. In addition, many of the Woolwich Academy–trained soldier artists in British North America had their drawings and watercolours transformed into prints for sale when they returned to Britain. This material was not widely circulated in Canada, and the growing population here was somewhat unaware of this garrisoned life. Toward the end of the nineteenth century the Canadian homegrown illustration business strengthened, thanks to immigration.

For different reasons during the two world wars, the authorities that ran the Canadian War Memorials Fund (CWMF) and the Canadian War Records supported the production of artists’ original prints and the mechanical reproduction of their artwork. The CWMF had to be self-sufficient, so the sale of prints associated with the larger paintings or drawings it commissioned was considered helpful—for example, a print of the massive painting of ruins, The Cloth Hall, Ypres, c.1918, by James Kerr-Lawson (1862–1939). Arthur Lismer made a series of sixteen lithographic designs depicting naval activity in Halifax Harbour, but at the time they were not big sellers. Indeed, many of the colour reproductions of the major First World War paintings, which were mainly by British artists, remained unsold for decades. The mood of the country had turned away from war.

The Canadian War Records program during the Second World War was government funded, so did not need to raise private money to keep its war art scheme afloat. Some individuals associated with the program promoted related graphic art projects, including poster and reproduction designs. Published by the Toronto printing firm of Sampson-Matthews, these images were intended for distribution during the conflict to military barracks and offices but could also be purchased for use in schools, libraries, banks, insurance companies, and shops. By 1943, the prints were hanging in Eaton’s store windows from coast to coast.

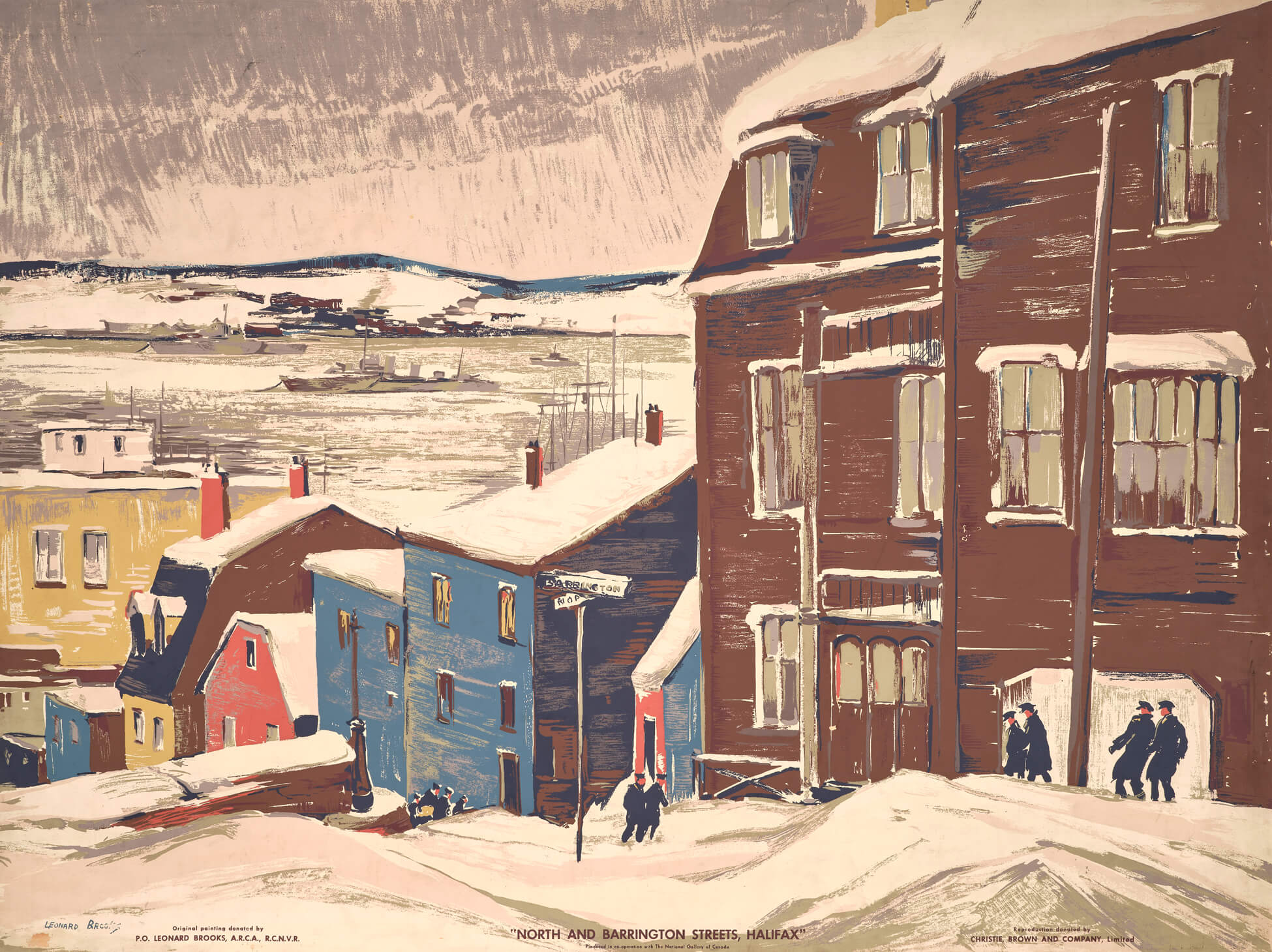

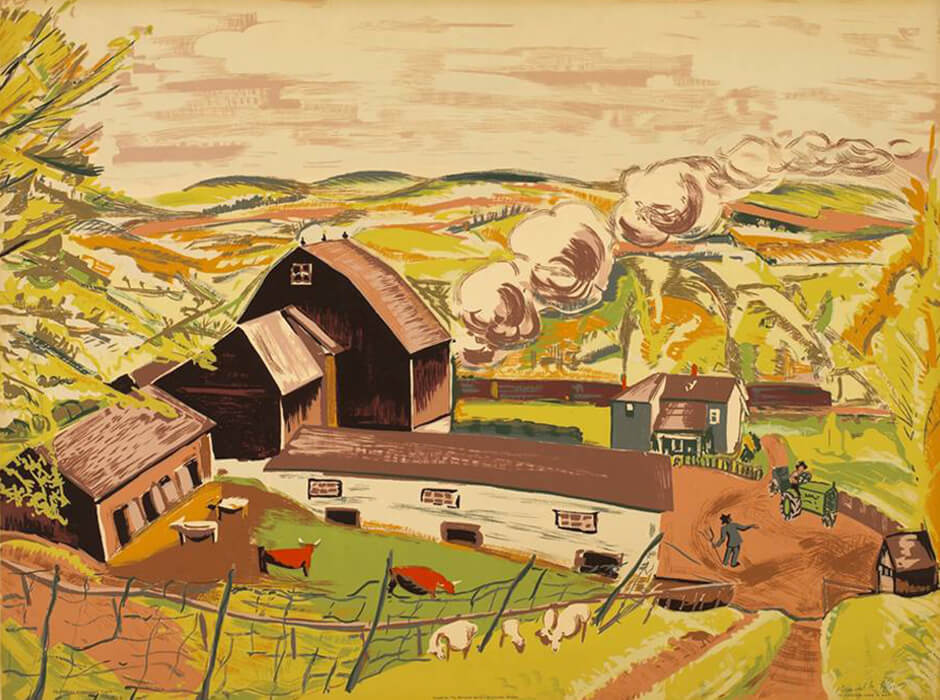

These reproductions—a majority featuring Canadian landscapes—were a success in terms of circulation, with close to 11,000 posters distributed to Canadian Forces bases and other locations. The most military in appearance is Halifax Harbour (North and Barrington Streets), c.1944, by Leonard Brooks (1911–2011), based on one of his official paintings. Others include A Caledon Farm in May, 1945, by Paraskeva Clark (1898–1986); Sugar Time, Quebec, 1944, by Albert Cloutier (1902–1965); and Mist Fantasy, 1943, by J.E.H. MacDonald (1873–1932). Propaganda was clearly the most important motive, and the program served the greater public good by building civil and service morale through art. It also provided limited income for some artists: contributors received ten prints they could sell themselves and a royalty of fifty cents on every print sold to the schools program.

A few artists chose to produce original prints in the form of lithographs, etchings, and drypoints, motivated by personal interest and, perhaps, a desire to make some money. Official war artist Carl Schaefer (1903–1995), for example, based his lithograph Crankshaft for Corvette, Marine Engine, 1942, an edition of four, on an ink-and-wash drawing he made during a visit to the John Inglis and Company weapons manufacturing plant in Toronto in the same year.

During the First World War, a number of the officially commissioned artists, such as Frederick Varley, also found employment in the commercial art field illustrating articles or providing cartoons for Canadian magazines. Varley illustrated the short war story “Peach” by soldier-journalist Carlton McNaught for The Canadian Magazine in December 1918.

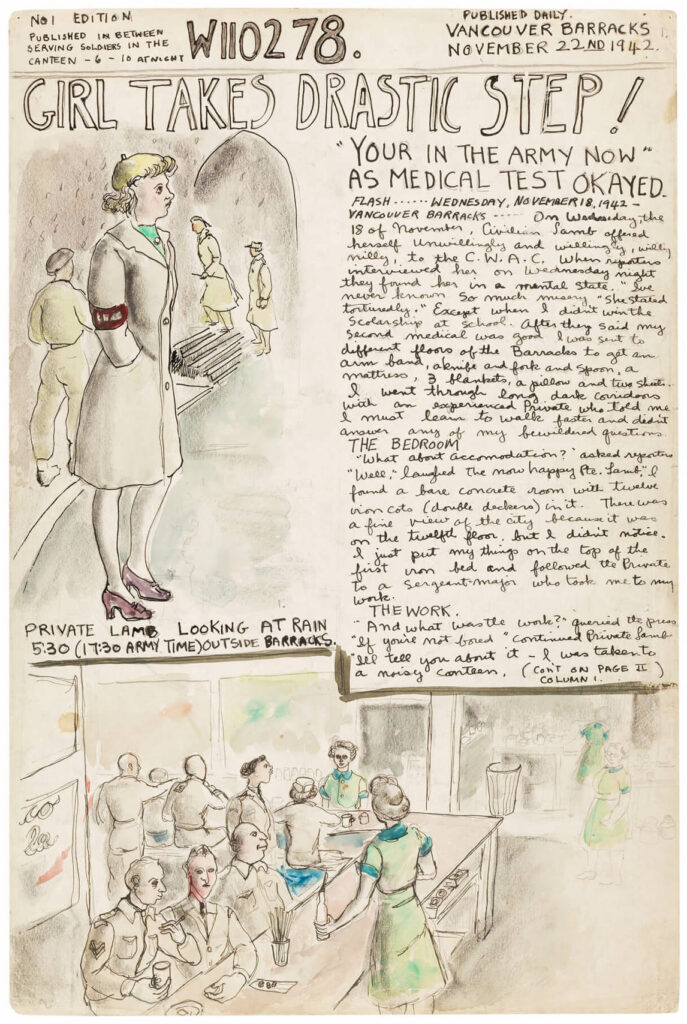

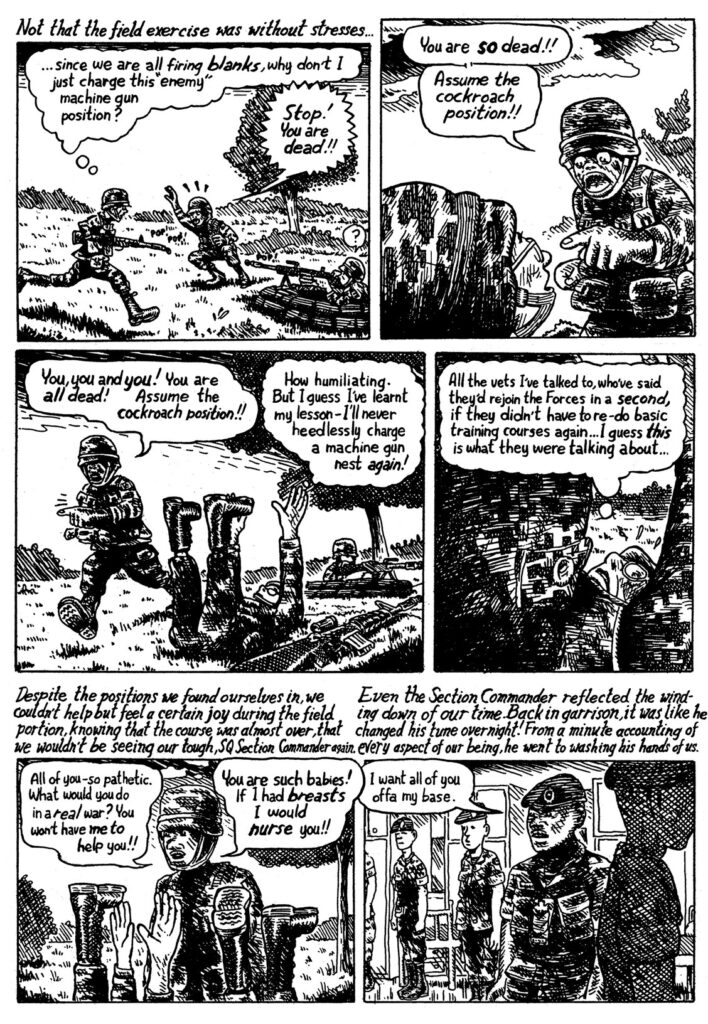

For private enjoyment, Second World War painter Molly Lamb Bobak (1920–2014) kept an illustrated diary published as Double Duty: Sketches and Diaries of Molly Lamb Bobak, Canadian War Artist (1992). CHIMO (2011) (the nickname, cheer, and mascot of the Canadian Military Engineers), by soldier and Canadian Forces Artists Program cartoonist David Collier (b.1963), is, similarly, a graphic novel and autobiographical account of the artist’s decision to re-enlist in the Canadian Army and go through basic training again at age forty in order to travel to Afghanistan.

In contrast, drawings produced by war artists had very different histories. During the twentieth century and earlier, most officially commissioned military oil paintings and sculptures were based on preparatory drawings, sketches, and watercolours. The authorities generally did not collect this preliminary work. It entered public collections only much later or after the artists’ deaths, if it had been preserved. Prime examples include the hundreds of preliminary sketches associated with the Second World War art of Alex Colville (1920–2013) that came to the Canadian War Museum in 1982, or the First World War sketchbook by Cyril Barraud (1877–1965) that entered the museum’s collection in 1989.

Soldier art, primarily on paper, was also little collected or identified until recently. Not only did the authorities consider it amateur in many cases, but they deemed it to be of personal rather than national interest. Reflecting recent evolving and expanding views about visual culture in wartime, however, soldier art became a major component of the Canadian War Museum’s touring exhibition Witness: Canadian Art of the First World War, 2014–19. Typical examples of soldier art include the detailed drawing Arras, Ruins, 1917, by André Biéler (1896–1989); the remarkable First World War sketchbooks of Edwin Holgate (1892–1977); and the dramatic and likely eyewitness sketches, such as Trench Fight, 1918, by artilleryman and illustrator Harold Mowat (1879–1949).

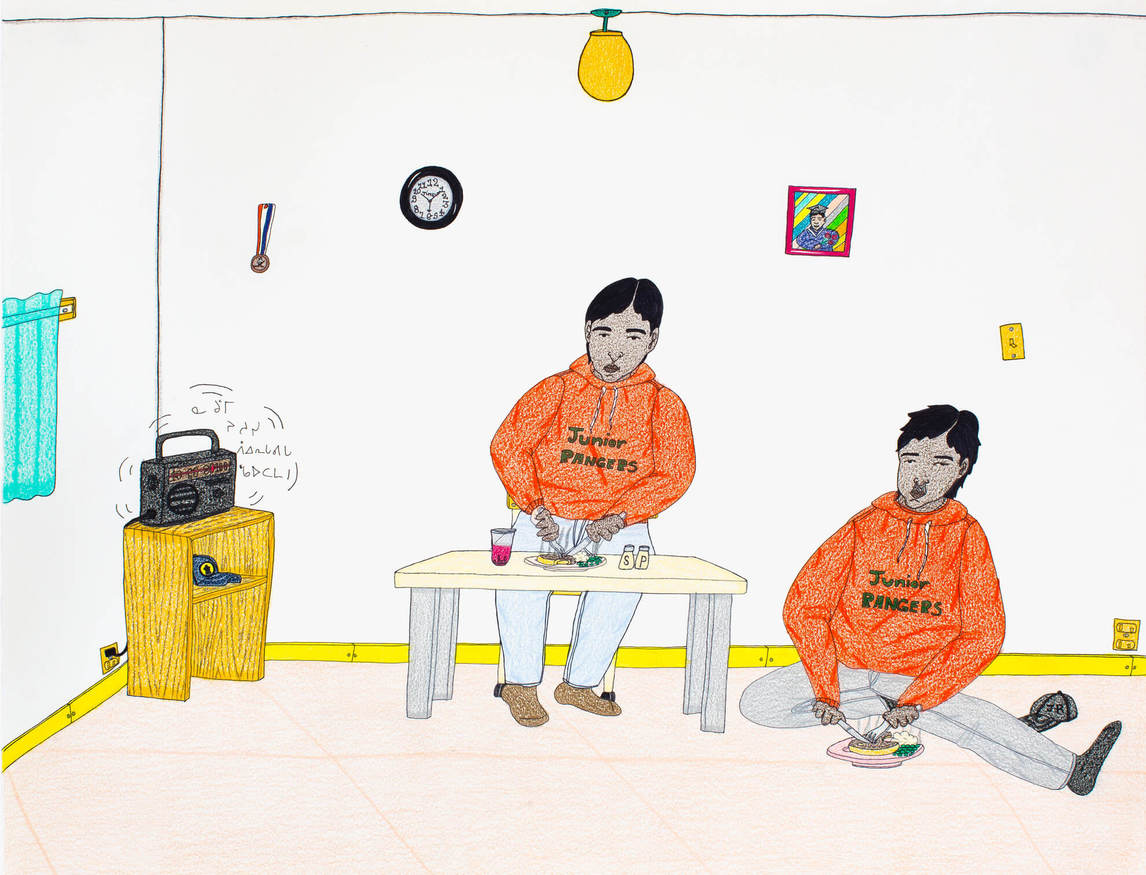

Although commercial printmaking and drawing became a notable mainstay of Inuit society in the twentieth century, initially subjects tended to be based on traditional hunting and fishing culture. CFAP uniquely encouraged one well-known Kinngait (Cape Dorset)–based Inuit artist to make a drawing based on his own military service as a Canadian Ranger. As a subcomponent of the Canadian Army Reserve, rangers live and work in remote, isolated, and coastal regions. The exquisite coloured-pencil drawing Rangers, 2010, by Tim Pitsiulak (1967–2016) depicts rangers unloading boats. Annie Pootoogook (1969–2016) was also inspired by these individuals and their service, and in Junior Rangers, 2006, she depicted two young Rangers taking a break at home.

Posters

The earliest war posters, dating from the nineteenth century in colonial Canada, were broadsides—official announcements created in printing offices using letterpress. As the technology advanced, in the early twentieth century they developed to include a prominent visual image alongside short captions.

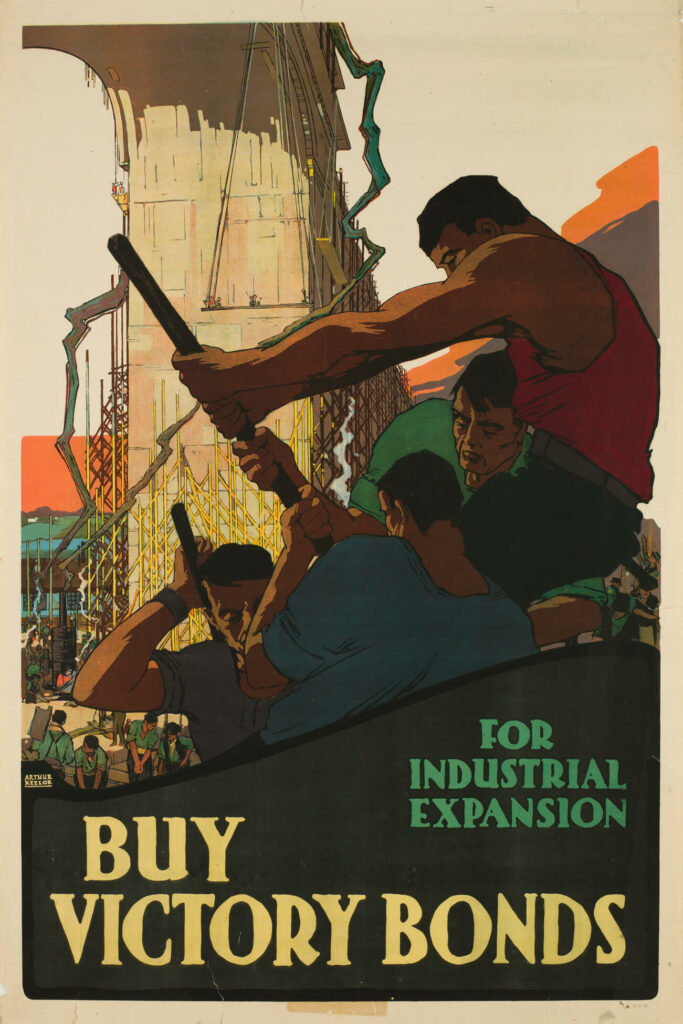

During the First World War, Canada used very effective posters to solicit recruits, secure war loans, urge conservation, and announce acceptable national policies relating to war. Most of these posters presented themes of patriotism, imperialism, or sacrifice, using fairly traditional texts and images. Among the artists who designed them were J.E.H. MacDonald and Arthur Keelor (1890–1953). MacDonald’s somewhat romantic Canada and the Call, 1914, advertises an exhibition of Canadian paintings intended to raise money for the Canadian Patriotic Fund, which gave financial and social assistance to soldiers’ families. Strong diagonal and vertical lines, bold lettering, and intense primary colours lend a contemporary flair to Keelor’s dramatic fundraising poster For Industrial Expansion, Buy Victory Bonds, c.1917.

Second World War designers include Montreal architect and illustrator Harry Mayerovitch (1910–2004), Toronto illustrator Clarence Charles Shragge (1904–1969), and Prince Edward Island artist Hubert Rogers (1998–1982). Both worked for the Wartime Information Board, established in 1942 to better coordinate propaganda for Canada’s fast-growing war effort. Rogers’s Attack on All Fronts, 1943, depicts a soldier with a machine gun, an industrial worker with a rivet gun, and a woman with a hoe. Because the Canadian armed forces were expanding so rapidly, essential industries such as farming were forced to recruit women and older male workers. As the poster illustrates, all were equally important to the war effort.

As the director of the Wartime Information Board’s Graphic Arts Division, Mayerovitch, in I was a Victim of Careless Talk, 1943, designed a chilling image of a dead man accusing viewers of causing his death at sea by gossiping. Its theme drew attention to the challenges faced by Canada’s sailors during the Battle of the Atlantic, and its potent design borrowed directly from Hollywood monster movie posters, in particular Frankenstein (1931). In many respects, however, the Second World War marked the end of the poster’s influence in conflict situations. With the development of television, it could no longer hold its own as the Western world’s propaganda weapon of choice.

Photographic and Digital Media

Once photography was invented in 1839, its usefulness as a documentary tool in wartime was swiftly recognized. In colonial Canada, cameras were used to record skirmishes and conflicts from Confederation in 1867 on, including the Fenian Raids, the Northwest Resistance, and the South African War. Photographs possess a unique capacity to document battle sites, regiments of soldiers, commanding officers, fortified positions, and the aftermath of battles, although for decades they followed the established traditions of painted war art. Generals were photographed with the same swagger as portraits, images of devastated battle sites aped the vast painted panoramas of earlier times, and photographs of shelled buildings and shattered landscapes drew on previous pictorial vocabulary to evoke death, grief, and mourning.

-

Passchendaele, Now a Field of Mud, November 1917

Photograph by William Rider-Rider

Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa -

Canadian Troops Passing through Ypres, Showing the Cloth Hall and the Cathedral, November 1917

Photograph by William Rider-Rider

Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa -

General Currie and General MacBrien at a Practice Attack near the Canadian Front, 1917

Photograph by William Rider-Rider

George Metcalf Archival Collection, Canadian War Museum, Ottawa

During the First World War, for example, three images by English official Canadian photographer William Rider-Rider (1889–1979) prove this point: the brooding panorama Passchendaele, Now a Field of Mud, November 1917, exemplifies battlefield imagery; Canadian Troops Passing through Ypres, Showing the Cloth Hall and the Cathedral, November 1917, displays the power of ruins to evoke emotion; and the portrait General Currie and General MacBrien at a Practice Attack near the Canadian Front, 1917, conveys something of the leadership characteristics admired in commanding officers.

But photography can also be physically manipulated, cropped, and faked and its meaning controlled by its context and presentation. The most egregious Canadian examples were by English official Canadian photographer William Ivor Castle (1877–1947), a master of composite photography. Castle’s massive photograph The Taking of Vimy Ridge, 1917, the highlight of an exhibition of Canadian war photographs in London only three months after the Canadian victory, is actually a composite photograph.

A number of artists based their paintings on official photographs. The Sunken Road, 1919, and German Prisoners, c.1919, by Frederick Varley make use of the same official photograph for some of the figures. Varley’s use of official photography as source material, however, was always interlaced with his use of sketches made on the spot combined with recollections of scenes he recorded in letters to his wife and others.

Whether official or personal, Second World War photography was largely documentary—for example, the famous 1941 portrait of Winston Churchill by Yousuf Karsh (1908–2013). Official artists were supplied with cameras, and many made use of them in the creation of their compositions—as Alex Colville did with Bodies in a Grave, 1946. Independent artists such as Jack Shadbolt (1909–1998) worked with their recollections of Holocaust photographs to create postwar masterpieces such as Dog Among the Ruins, 1947.

Photography was used in poster design, as in the Canadian Women’s Army Corps recruiting poster Why Aren’t You in Uniform?, n.d., which includes a photograph of a member of the Canadian Women’s Army Corps working on a vehicle engine. Perhaps demonstrating the then lesser status of the medium, the names of the designer, the photographer, and the publisher are not noted on the poster. The most famous photographs of the period may well be of Veronica Foster, “the Bren Gun Girl,” taken under the auspices of the National Film Board’s Still Photography Division in 1941. The photographer is unknown.

Participants with the Canadian Forces Artists Program (CFAP) are almost equally divided between photographers and painters. Photographers include Métis artist Rosalie Favell (b.1958), who, in 2017, took pictures of a number of Canadian Rangers in their northern environment, such as beaming Ranger Sheila Kadjuk (Chesterfield Inlet) 1st Canadian Ranger Patrol Group, Rankin Inlet, Nunavut. This image shows that war art and photography are inextricably linked—and increasingly so in the digital age. Today, the world relies on photography in its still, moving, and digitized formats to bring home the horrors of worldwide conflicts and the experiences of their military personnel, and everyone includes photography in their war art vocabulary. It provides an inspiration, just as, nearly two hundred years ago, photographers drew on military painting for their creativity.

Nevertheless, many photographers still explore issues relating to the authenticity of photography. Dead Troops Talk (A Vision after an Ambush of a Red Army Patrol, near Moqor, Afghanistan, Winter 1986), 1992, by Vancouver resident Jeff Wall (b.1946) is a remarkable essay on the permeability of art, truth, history, and photography. Wall looks back to history painting for this photograph of an event he never witnessed and only imagined. Dead men do not talk, but his thirteen sometimes severely wounded Soviet soldiers lounge around a shell crater, chatting. Here, war is normalized, but Wall, in undertaking the exercise, shows us how abnormal it really is.

CFAP photographer Althea Thauberger (b.1970) partially staged Kandahar International Airport, 2009, with its depiction of twelve armed and smiling female soldiers running toward the viewer along the tarmac in a war zone. They wear their own uniforms and bear their own weapons in a real place, but the artist directed their run. For those with preconceived expectations of military environments, this scene is not normal, yet in its content it is factually accurate. Similarly, Leslie Hossack (b.1947) edits all signs of human life from her images to increase their intense if not disturbing atmospheric qualities, as can be seen in Blast Tunnel, The Diefenbunker, Ottawa, 2010, which depicts a Cold War-era nuclear bunker.

Film, Video, and Television

Government-sponsored film production documenting the Canadian military began in early 1915 and, today, nearly 70,000 feet of First World War film survives in the Library and Archives Canada collection. Lest We Forget, a major early documentary about Canadian participation in this war created in 1934, includes much of this footage.

-

Jane Marsh Beveridge, Women Are Warriors (film still), 1942

Short film, 16 min

National Film Board of Canada, Montreal -

Jane Marsh Beveridge, Proudly She Marches (film still), 1943

Short film, 18 min

National Film Board of Canada, Montreal -

Jane Marsh Beveridge, Wings on Her Shoulder (film still), 1943

Short film, 10 min

National Film Board of Canada, Montreal

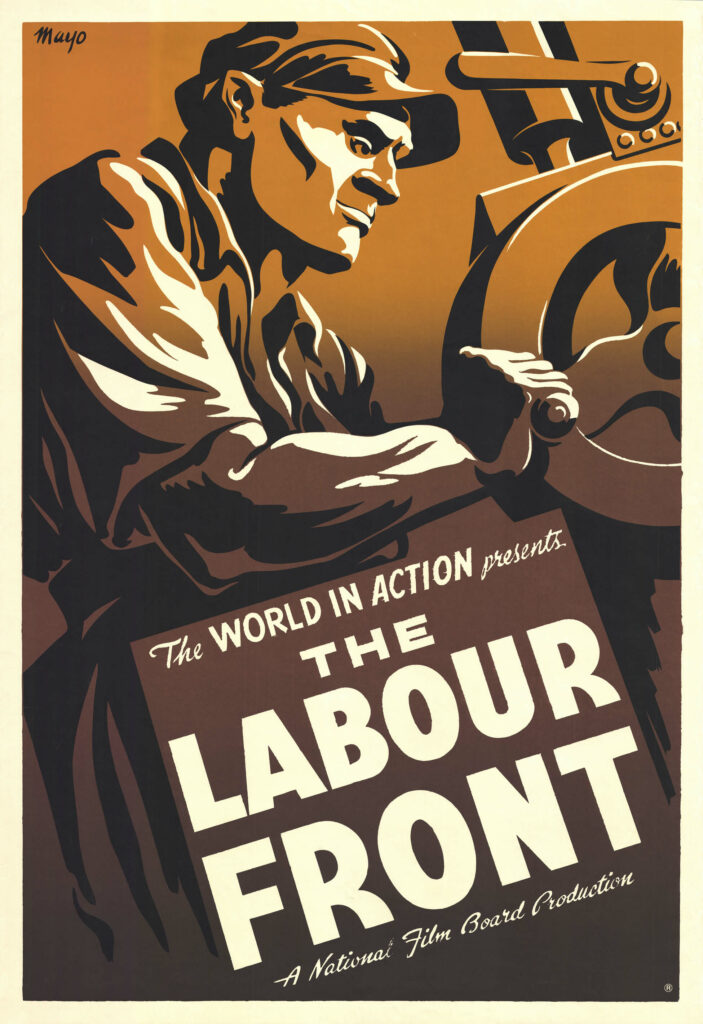

In the first year of the Second World War, the government established the National Film Board (NFB), which replaced the Canadian Government Motion Picture Bureau. The NFB initiated a popular series entitled Canada Carries On, 1940–59. It was spearheaded by Scottish pioneering filmmaker John Grierson (1898–1972) and intended primarily as morale-boosting propaganda for Canadian audiences, and some eight hundred theatres across Canada received a new episode every month. Jane Marsh Beveridge (1915–1998) directed many episodes before she resigned from the NFB in 1944. She is best remembered for those she directed about women and war: Women Are Warriors (1942); Proudly She Marches (1943); and Wings on Her Shoulder (1943).

The Canadian Army Film Unit (CAFU), created in 1941 by the Department of National Defence, worked independently. Unlike the NFB, its footage was the work of more than two hundred Canadian soldiers, sailors, and airmen working as combat camera operators shooting in real time behind the lines and in battle. In all, CAFU created over two thousand stories about the Canadian Army in wartime. Its greatest reach came with the internationally distributed series of Canadian Army Newsreels, 1942–45, with each reel containing between five and ten parts, each lasting a few minutes. Newsreel 65 includes coverage of Canadian official artists Alex Colville and Bruno Bobak (1923–2012) sketching near battlefields. There was significant conflict between the NFB and the CAFU over which department would control the filmed documentation of Canada at war.

Until the 1970s, Canadian feature filmmaking was subsumed in the American Hollywood machine. The lone exception was Carry on Sergeant! (1928), a silent movie that was produced just as “talkies” were coming to the forefront. The unfortunate timing and the fact that it featured a scene between a Canadian soldier and a French prostitute led to its immediate and virtual disappearance from movie theatres.

Despite the revival of the Canadian film industry in the late twentieth century, it is only recently that interest has turned to war films. Actor-director Paul Gross (b.1959) has been at the centre of Canada’s commercial war filmmaking business with his First World War Passchendaele (2008) and his Hyena Road (2015), set in Afghanistan. One significant Canadian history documentary film that received worldwide recognition is Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance (1993) by Abenaki director Alanis Obomsawin (b.1932), about military involvement in the Oka Crisis.

Television’s relationship with war has been mixed. One result of the airing of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation’s Second World War documentary series The Valour and the Horror, 1992, directed by brothers Terence McKenna (b.1954) and Brian McKenna (b.1945) was a subsequent Canadian Senate subcommittee inquiry focusing on its lack of historical accuracy—a carelessness that upset many veterans. Less passionately received by the public were two other series: the fictional Bomb Girls, 2012–13, which profiled the stories of four women working in a Canadian munitions factory during the Second World War; and The Great War, 2007, starring Justin Trudeau (the current prime minister) as a First World War hero. Canada’s war art has been well served by documentary films still shown on television, with the First World War’s Canvas of Conflict (1996), directed by Katherine Jeans (b.1960), and the Second World War’s Canvas of War (2000), directed by Michael Ostroff (b.1950).

The ongoing Canadian Forces Artists Program (CFAP) has attracted a number of innovative filmmakers and videographers, including Sophie Dupuis (b.1986), who completed a documentary about her Pacific sea voyage with the Canadian navy. Simone Jones (b.1966), a multidisciplinary artist who works with film, video, sculpture, and electronics, made a creative documentary based on her time with a search and rescue team at Canadian Forces Base Gander in Newfoundland.

Swiss-born Thomas Kneubühler (b.1963) undertook a series of videos and photographs about navigating the darkness of the Arctic night using the light of illuminated navigation aids at Canadian Forces Station Alert near the North Pole. Charles Stankievech (b.1978) also worked there and created the visually arresting and moving soundscape The Soniferous Æther of the Land Beyond the Land Beyond, 2012. Andrew Wright (b.1971) was challenged very early on in the CFAP program to persuade his sailor subjects on board HMCS Toronto that there was more to photography than head and shoulders portraiture.

The shift from painting to digital media was not limited to these artists. In 2011, under the auspices of CFAP, nichola feldman-kiss was embedded with the United Nations Mission in Sudan that was intended to ameliorate the horrific consequences of that country’s civil war. after Africa \ “So long, Farewell” (sunset) / a yard of ashes (continuous cross dissolve) / “Oh! How I hate to get up in the morning!” (sunrise), 2011, is a reinterpretation of the impossibility of escaping trauma because it is always there with you, as she demonstrates in a haunting video showing a girl at a piano isolated by the endless circling of the camera that films her.

Following her CFAP assignment, in 2015, Mary Kavanagh (b.1965) made Track of Interest: Exercise, Vigilant Eagle 13, which addresses the continuing spectre of nuclear war. Kavanagh flew on the “track of interest,” a civilian jet under attack, during a live-fly, simulated hijacking in Exercise Vigilant Eagle 13, an elaborate tri-national exercise (United States, Canada, Russia) staged across Alaskan and Russian airspace by North American Aerospace Defense Command and the Russian Federation Air Force. Structured as a sequence of double images, the film juxtaposes pictures of military forces with some of the powerful natural strengths of the Alaskan North.

The styles followed by these artists are not necessarily documentary or filmic, and they vary enormously depending on whether their backgrounds are in film, video, photography, or painting. For a majority of them, video in particular provides an important perspective on any meaningful experience they might wish to convey to their viewers, either through this medium or in tandem with another. The technical equipment required for video today is lightweight: the digital universe has made multimedia approaches to the subject matter of war and conflict not only practical but the norm.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements