Trench 2017

Adrian Stimson, Trench, 2017

Five-day interdisciplinary performance

Collection of the artist

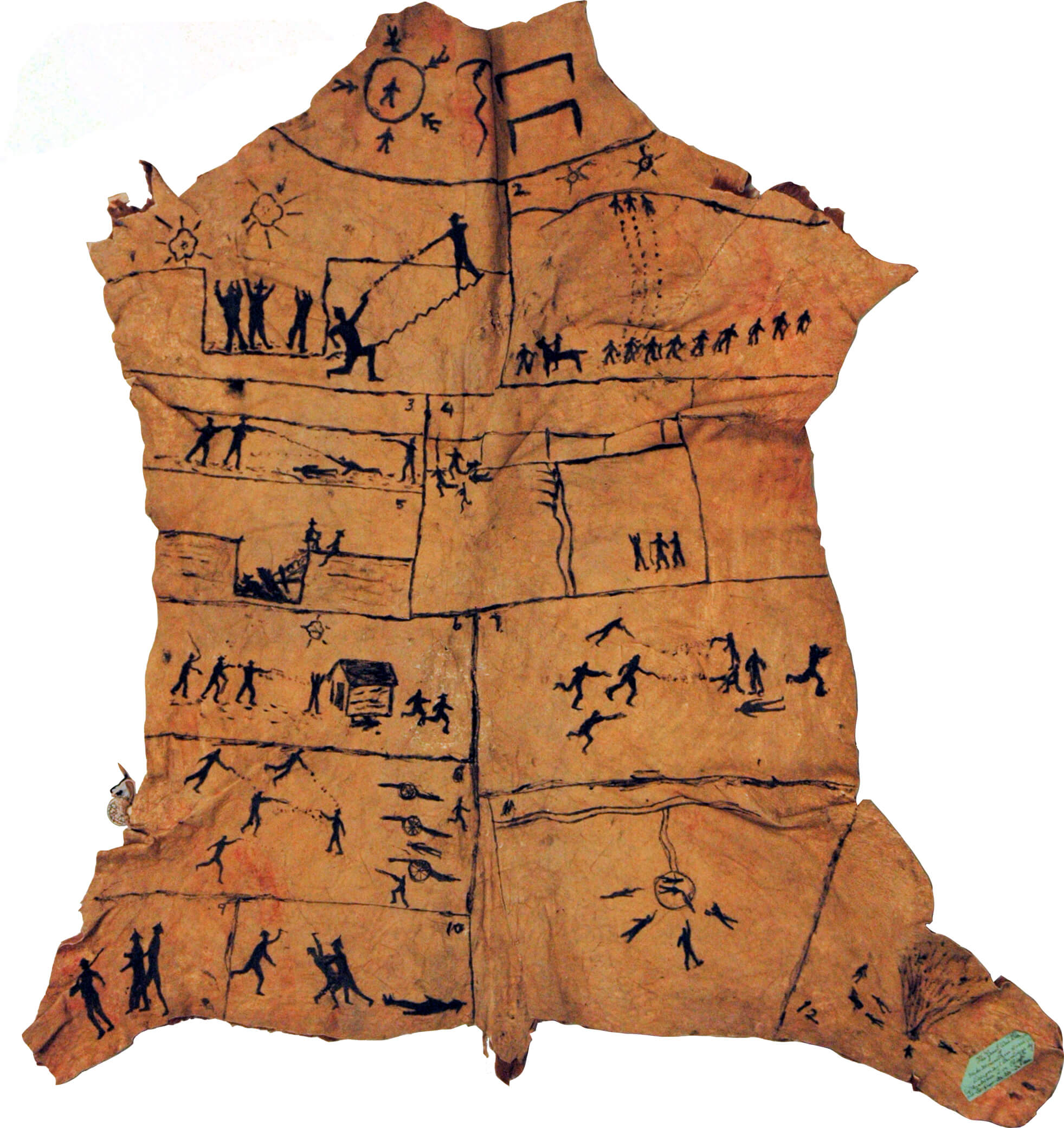

Trench commemorates the approximately 4,000 Indigenous soldiers who served in the First World War. This art performance by Adrian Stimson (b.1964) took place on land near the artist’s family home in the Siksika (Blackfoot) Nation, an hour’s drive east of Calgary. Working from dawn to dusk over five days (May 23–27), Stimson dug a six-foot-deep trench. Guided by First World War manuals, he dug his trench in the U-shape pattern, which is also the Niitsitapi (Blackfoot) symbol of war, and shored it up with two hundred and fifty sandbags. The U-shape appears on the War Exploit Robe, n.d., of First World War Kainai (Blood) soldier Miistatosomitai (Michael Mountain Horse). The robe was designed by Eskimarwotome (Ambrose Two Chiefs) (c.1891–1968), and it documents Miistatosomitai’s significant First World War experiences, including many deadly encounters with opposing forces, in a black pictograph narrative on cowhide.

Stimson’s performance references Niitsitapi cultural practices that put the body under duress to enable healing. He hoped his toil would draw attention to the incompleteness of Indigenous First World War history and make it whole and worthy of honour.

Stimson participated in the Canadian Forces Artists Program and was stationed at Forward Operating Base Ma`sum Ghar and in Kandahar in Afghanistan in 2010. His performance art looks at identity construction, specifically the hybridization of the Indian, the cowboy, the shaman, and his Two Spirit (third gender) being, Buffalo Boy.

Performance art is rare in Canadian war art, and Stimson’s Trench is unique. It shares similar goals to those that motivated U.K. artist Jeremy Deller (b.1966) to break down barriers between past and present. Deller memorably commemorated the opening day of the 1916 Battle of the Somme with a performance piece entitled we’re here because we’re here—the words of a First World War soldier song. On July 1, 2016, Deller organized some 1,600 volunteers, all men, to dress in replica First World War British Army uniforms and appear in groups at railway stations, shopping centres, and other places to represent an individual soldier who died on the first day of the battle. When approached by members of the public, they did not speak but instead handed out cards bearing the name, age, and regiment of the person they represented.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements