“Sewing Up the Dead” 1885

James Peters, “Sewing Up the Dead”: Preparation of North-West Field Force Casualties for Burial, April 25, 1885

Albumen print on paper, 7.2 x 9.4 cm

Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa

Taken during the Northwest Resistance in 1885, “Sewing Up the Dead” is one of the earliest wartime photographs in Canadian history. It is an image that records the preparation of North-West Field Force casualties for burial, and a reminder of the brutal consequences of battle. James Peters, himself a soldier, used a state-of-the-art Marion Academy twin-lens reflex camera, which could be loaded in advance with twelve glass plates. He took ten sets of plates with him into battle, and of the sixty-three that survived (glass is notoriously prone to damage), most featured fellow soldiers engaged in regular activities. He often captured images from horseback, and he rarely took pictures of the Métis. Following the conflict, in 1906 he destroyed the negatives; today, only prints survive. Notably, however, he provided captions.

When it came to dead bodies, Peters was respectful of his fellow soldiers, as can be seen in “Sewing Up the Dead.” In another image, however, the body of Alexander Ross (one of the last Métis killed in defence of the village of Batoche) is depicted spreadeagled as he fell and afforded the bleak caption “He Shot Capt French,” a man who was a well-regarded troop commander.

The aversion to making images of one’s deceased fellow soldiers forms a continuum in the history of Canadian war art. During the First World War, the Canadian War Records’ Lord Beaverbrook instructed his official photographers, “Cover up the Canadians before you photograph them… but don’t bother about the German dead.”1 This directive permitted Frederick Varley (1881–1969) to add a number of German bodies to his painting The Sunken Road, 1919. Drawing inspiration from a 1916 official photograph, he added in gobs of red paint to ensure greater realism.

In the middle of the Second World War, Charles Comfort (1900–1994) painted Dead German on the Hitler Line, 1944, a cadaverous image akin to that of Peters’s Alexander Ross. Based on Comfort’s diary recollections, it would seem the body had been lying there for a month. To his credit, the artist retrieved the dead man’s identity disk and turned it over to a chaplain, who subsequently arranged for the body’s burial.

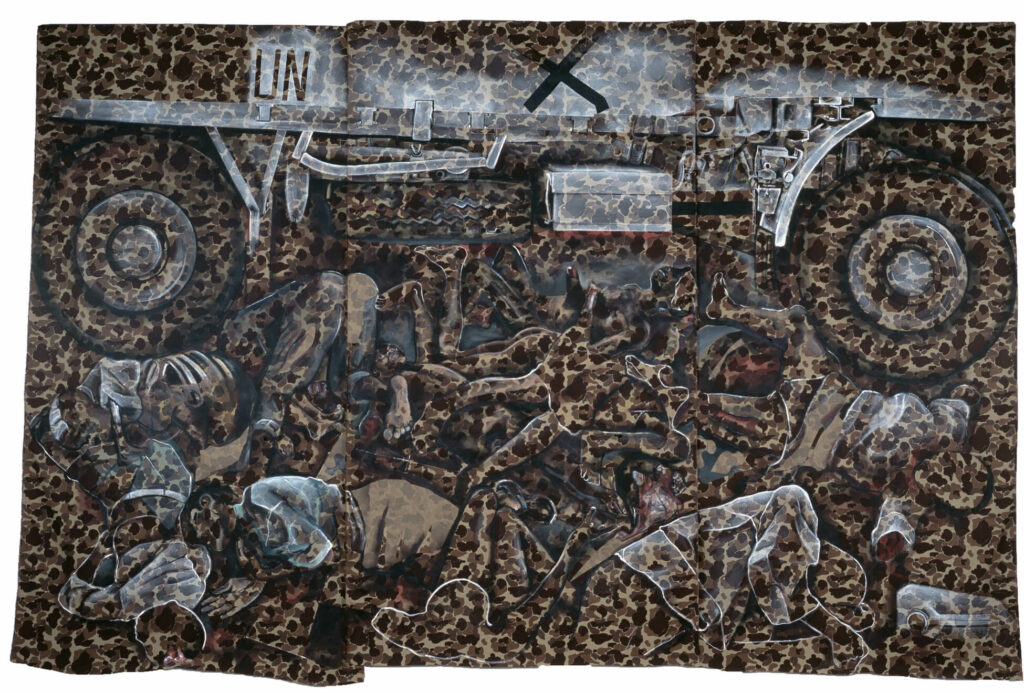

On rare occasions, Canadian artists have also chosen to depict wartime genocide. Alex Colville’s (1920–2013) depictions of the death pits at Bergen-Belsen, such as Bodies in a Grave, 1946, are horrific. Contemporary war artist Gertrude Kearns (b.1950) excoriates military intervention in her representation of the 1994 Rwandan genocide dead in her massive and overwhelming Mission: Camouflage, 2002: here dozens of unidentified bodies lie entangled below a white United Nations jeep. In Canada, genocide is captured by Daphne Odjig’s (1919–2016) fiery figurative swirl, Genocide No. 1, 1971. In this painting, she addresses colonial violence and the trauma experienced by Indigenous peoples in Canada decades before the government gave their suffering a name.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements