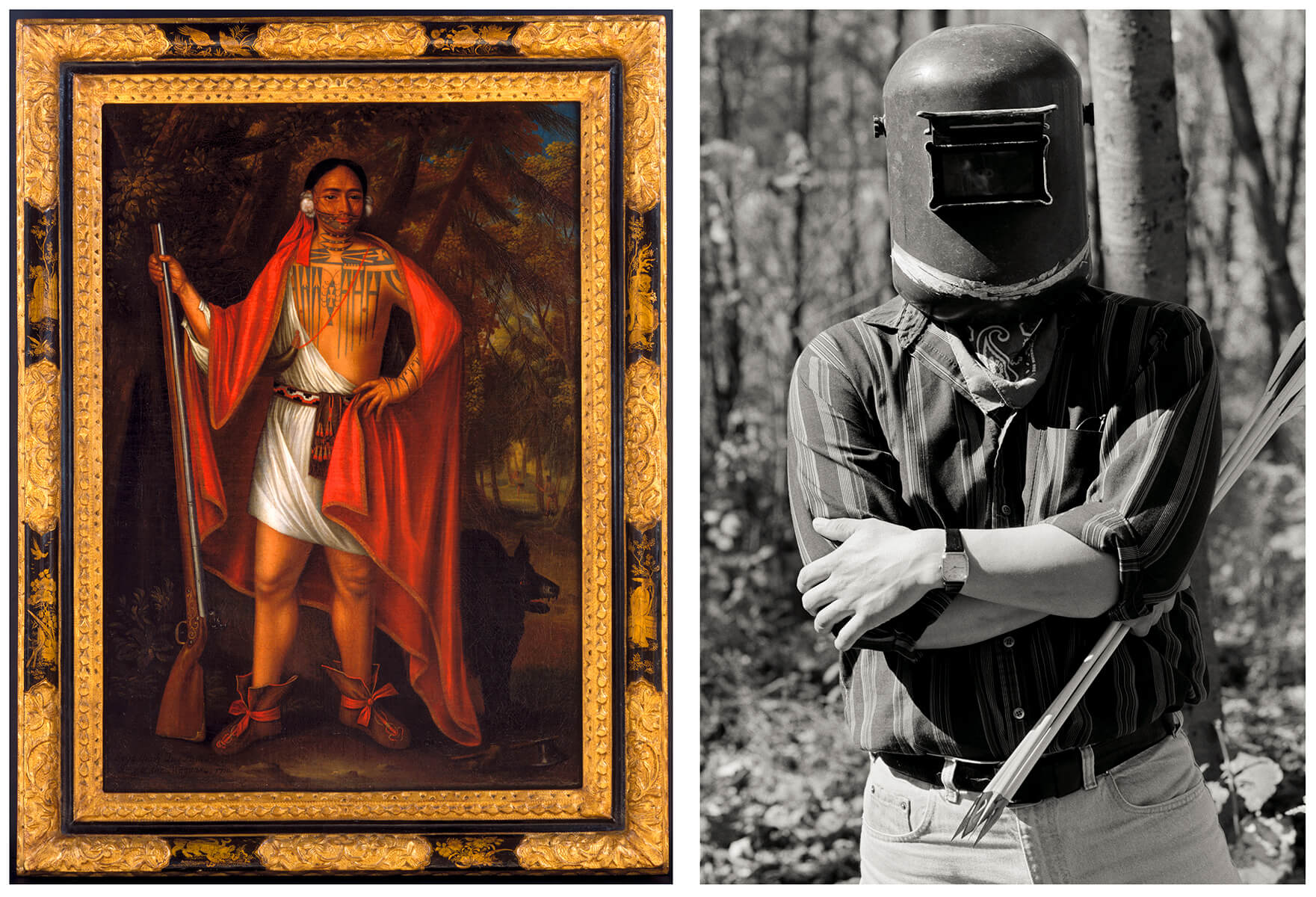

Sa Ga Yeath Qua Pieth Tow, King of the Maquas 1710

John Verelst, Sa Ga Yeath Qua Pieth Tow, King of the Maquas, 1710

Oil on canvas, 91.5 x 64.3 cm

Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa

In 1710, a delegation of four Indigenous leaders—three Haudenosaunee and one Anishinaabe—travelled to London with British military leaders seeking support against competing French interests in North America. There they met Queen Anne, who commissioned portraits of them from the London-based Dutch artist John Verelst (c.1675–1734). Sa Ga Yeath Qua Pieth Tow, King of the Maquas [Mohawks] portrays Thayendanegea’s (Joseph Brant) grandfather, Sagayeathquapiethtow, who died shortly after he returned to Canada. Notably visible are his tattoos, though their precise meaning is unclear. Haudenosaunee tattoos commemorated personal achievements in battle but also connections to family, society, and place, as well as more abstract concepts relating to Indigenous worldviews.

Known as the Four Kings, the portrait series also includes depictions of the other leaders, identified at the time as Ho Nee Yeath Taw No Row “King of Generethgarich”, Etow Oh Koam “King of the River Nation”, and Tee Yee Neen Ho Ga Row, “Emperor of the Six Nations”. All four images were later transformed into mezzotint prints by artists, including Anglo-French printmaker John Simon (1675–1751), and sold widely. The oil paintings remained in England in the Royal Collection until 1977, when Library and Archives Canada acquired them.

Jeff Thomas (b.1956) is an award-winning Haudenosaunee photographer whose work, like that of his compatriot Shelley Niro (b.1954), interrogates the place of Indigenous peoples in Canada. In 1990, he created a photographic diptych featuring Sagayeathquapiethtow and Steve Thomas as part of a portfolio. Thomas, an Onondaga, wears a welding helmet and carries a handful of arrows. He is photographed outside his home on the Six Nations reserve in Ontario. This is the land Thayendanegea (representing the Six Nations) was given (but without title, and now much reduced in size) by the British in compensation for Indigenous war losses during the American War of Independence (1775–1783).

In Thomas’s work, the juxtaposition of the images raises questions about the interrelationship of the two Indigenous figures in space and time. Sagayeathquapiethtow holds a gun, a European import, while Thomas, nearly three hundred years later, holds arrows, a pre-settlement weapon. Sagayeathquapiethtow is tattooed while Thomas wears a striped shirt and decorated neckerchief that is visually evocative of this element of the painting but freighted with Western rather than Indigenous associations. Thomas’s open-visor helmet implies protection in the same way that the open-jawed dog or wolf adjacent to Sagayeathquapiethtow does, but the difference colonization and the introduction of steel make to protection possibilities is underlined. Finally, Sagayeathquapiethtow’s verdant background is an imagined and westernized version of a sparsely peopled pine and deciduous landscape in southwestern Ontario, but Thomas’s treed late twentieth-century scene is imagined as wild and largely unpeopled, implying a pre-contact wilderness rather than the more urban reality that is today’s Six Nations reserve.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements