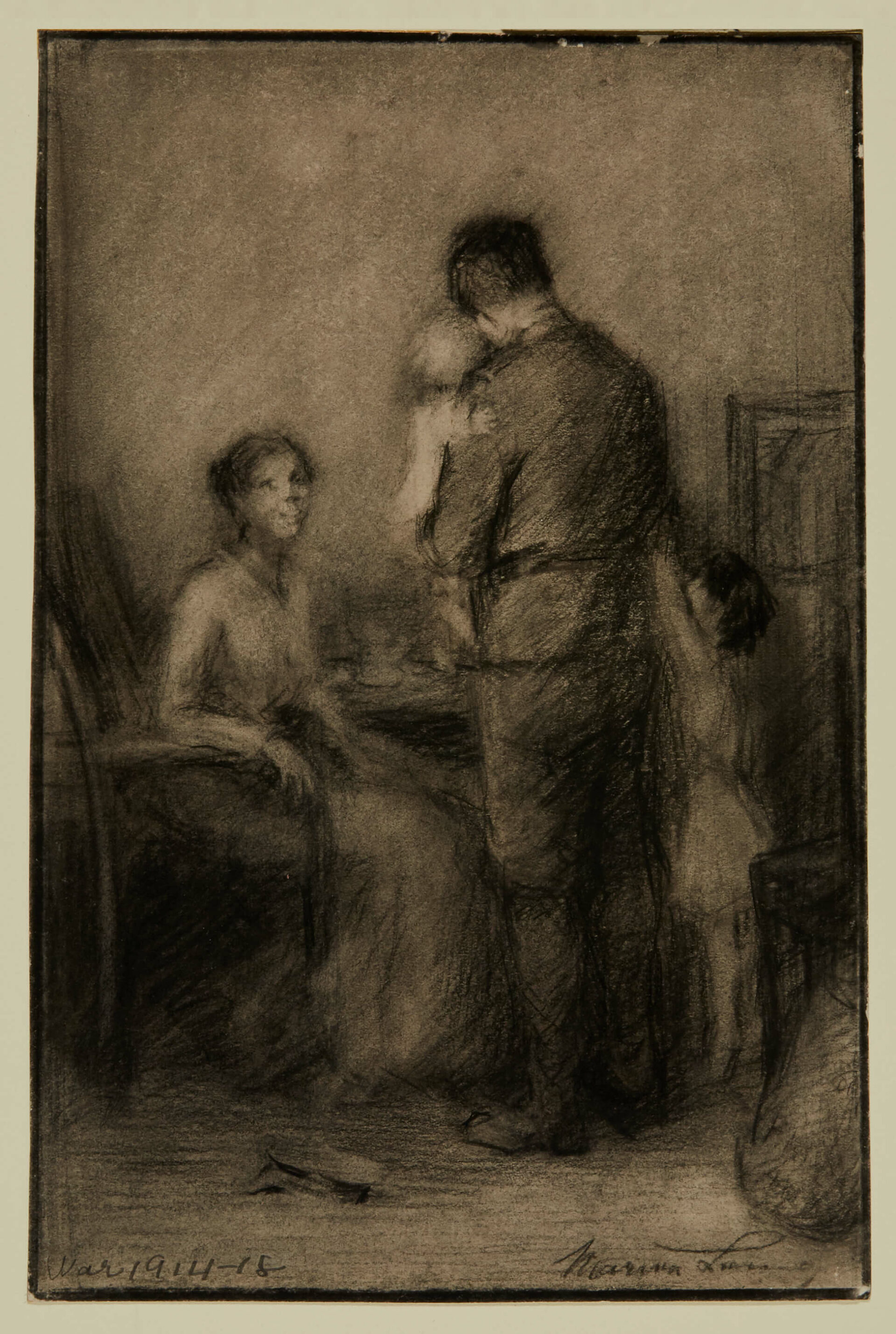

Home on Furlough 1915

Marion Long, Home on Furlough, 1915

Charcoal on paper, 28.7 x 18.6 cm

Art Gallery of Hamilton

In 1915, Marion Long (1882–1970) contributed three drawings to The Canadian Magazine that provide a fresh interpretation of the First World War from a woman’s point of view. These images were no doubt directed at women readers who empathized more with the impact of the conflict on the domestic sphere than with events occurring on foreign battlefields far from their own experience.

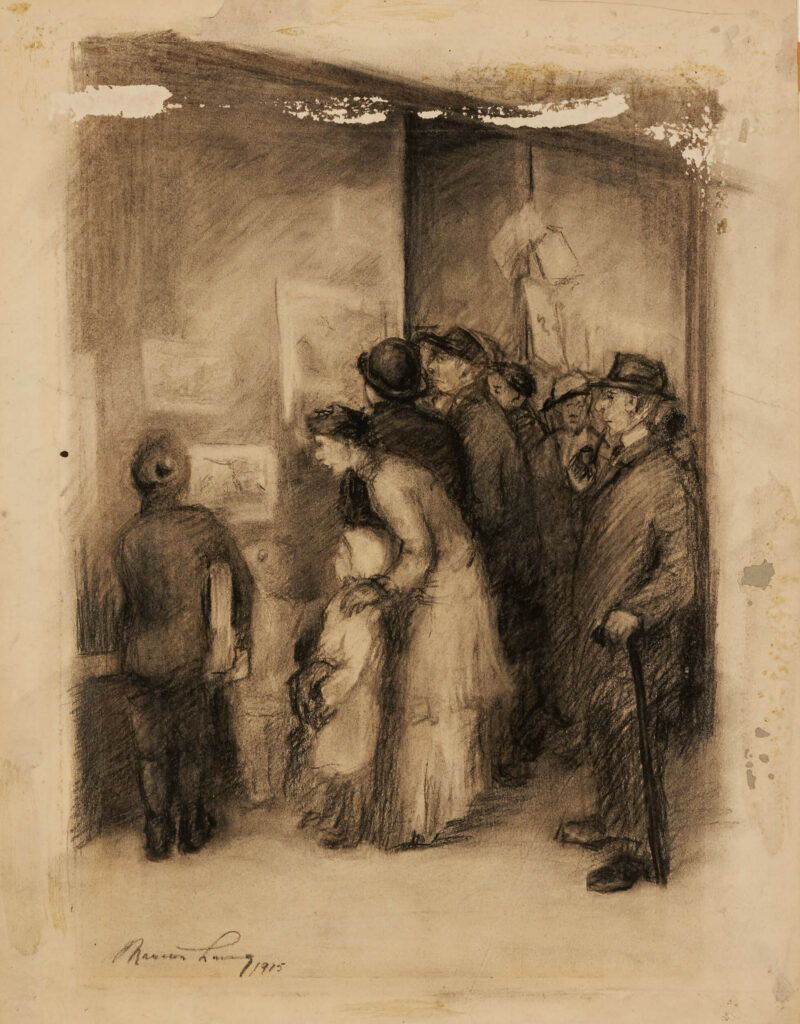

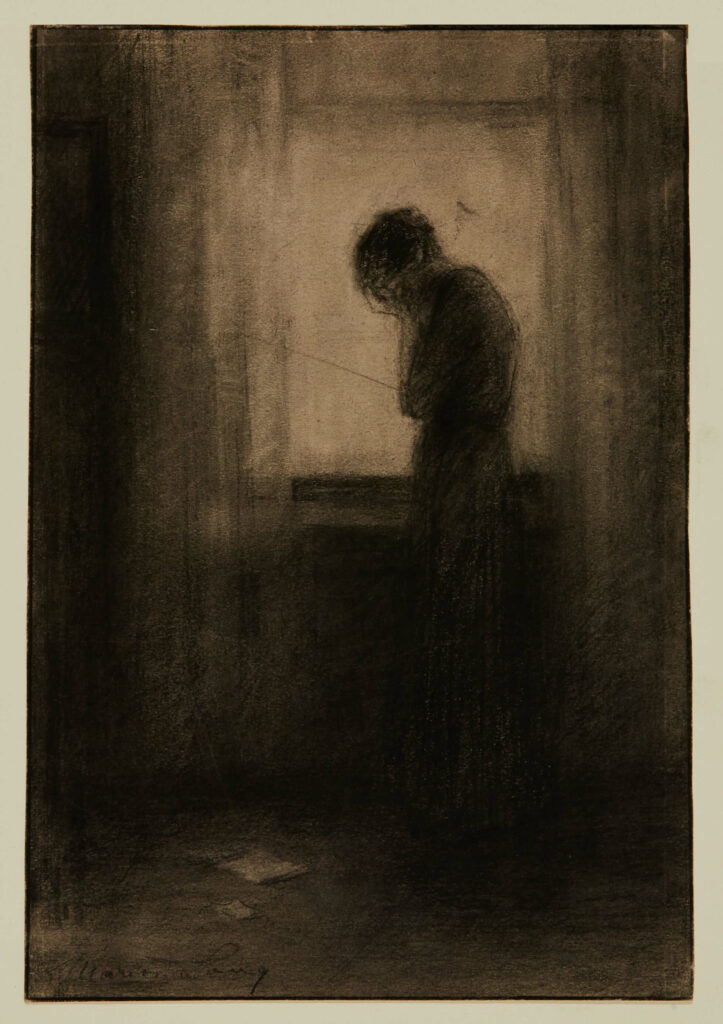

Home on Furlough depicts a mother seated in a chair looking lovingly at her uniformed husband, whose back is toward us. He holds their baby in his left arm, while his young daughter reaches up to him on his right. Another drawing in the published series is Looking at the War Pictures, 1915, showing the mother and her daughter studying war photographs in a store’s front window, possibly a newspaper office or newsagent’s shop. In Killed in Action, 1915, the woman stands silhouetted against a window, her head bowed into her hands, with the telegram bearing the tragic information lying at her feet. Together, the three images form a narrative of the experience of many women: the husband’s rare visit home (if not yet overseas), the daily checking on war reports, and the heart-stopping moment when bad news arrives.

Long’s pictures contrast with posters and official war art, which gave women supporting military-related roles during the conflict. Women Making Shells, 1919, by Henrietta Mabel May (1877–1971), for example, depicts women taking on men’s work in an armaments factory. Women’s perspectives on war are rare in Canadian military art and not much published or displayed. During the First World War, however, magazine illustration provided an important opening for female artists in the absence of many male artists overseas.

Like Long, Paraskeva Clark (1898–1986) also thought that the real story of war—in her case the Second World War—was to be found in the home. She dutifully depicted uniformed airwomen in her official war commission, but her Self-Portrait with Concert Program, 1942, sensitively betrays her concern for her Russian family. Similarly, the fragile protagonist in The Soldier’s Wife, 1941, by Elizabeth Cann (1901–1976) tells us that even for a woman far from the fighting, war is not really at a distance but very real, close, and frightening.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements