Through the visual culture of war, we can discern Canada’s evolving political environment and social values. What is included in officially sanctioned war art programs is telling, along with how art and objects are exhibited in relation to each other in museum collections. Representations of Indigenous peoples and women have changed drastically over time, in line with shifts in society at large, as have the ways in which matters such as propaganda, religion, violence, identity, and protest are treated by artists.

Official War Art

The production of artistic images is embedded in power relationships that, in turn, help to perpetuate the structures of authority within society. Many of the countries that participated in the global wars that have occurred since 1900, for example, have established and continue to support official war art schemes. These programs sustain and document approved government military activities and, to varying degrees, act as sites of memory for events the authorities wish to be remembered. The best-known Canadian national visual records of war are the four official war art programs: the First World War Canadian War Memorials Fund (CWMF), the Second World War Canadian War Records (CWR), the Cold War Canadian Armed Forces Civilian Artists Program (CAFCAP), and the current Canadian Forces Artists Program (CFAP).

During the First World War, Canadian-born businessman Sir Max Aitken (later Lord Beaverbrook) led the initiative to found the Canadian War Memorials Fund, and it was mostly privately funded. Living in England and immersed in a culture of stately homes wallpapered with military portraits and battle scenes, Beaverbrook experienced war art not only as a historical record but also as an expression of national identity, and he sought to replicate this context for Canadians. Fulfilling this goal, the post-conflict exhibitions organized by the CWMF earned recognition for Canadian wartime achievements and artists and asserted Canada’s national independence.

In the Second World War, artists lobbied hard to duplicate Beaverbrook’s scheme, believing that, in a “total” war, artists had an important role to play in communicating information and documenting shared events. Government support for a war art program, however, came only after three years of conflict, when the Canadian War Records was established.

During the Cold War—the lengthy period of global geopolitical tension dominated by the arms race between the United States and the Soviet Union—and the simultaneous overseas peacemaking and peace-building engagements, artists and bureaucrats were clearly far less focused on fostering war art schemes. The Canadian Armed Forces Civilian Artists Program was founded in 1968, more than twenty years after the Second World War scheme ended and the Cold War began, and was discontinued without much fanfare in 1995.

Pride in Canada’s contributions to global security during the post–Cold War period, beginning in 1989, revitalized interest in the public value of war art, and in 2001 the Department of National Defence established the Canadian Forces Artists Program. It is the only official program that encourages all the arts, including music, poetry, and drama, though visual art dominates. Furthermore, it allows artists great freedom, including the right to explore protest and anti-war themes and, in addition, to keep the art they produce under the scheme. As Canada participates in the Campaign against Terrorism, CFAP encourages artists to investigate how conflict and war shape and reshape who we are as Canadians and fosters increasing external critical evaluation of the work as art rather than as history.

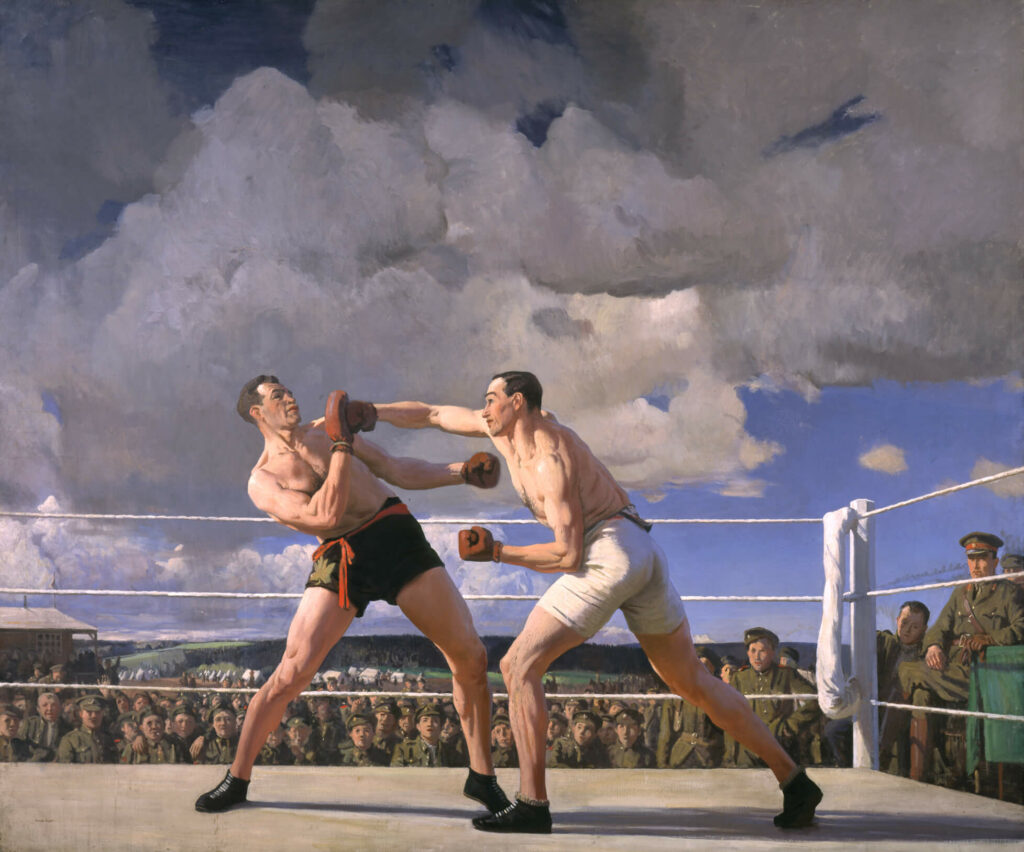

These four official military art programs together represent an important, but incomplete, visual record of the country’s martial achievements. The CWMF and the CWR both produced somewhat heroic paintings, such as Canadian Artillery in Action, 1918, by Kenneth Forbes (1892–1980) and Per Ardua Ad Astra (the Latin air force motto, “Through adversity to the stars”), 1943, by Carl Schaefer (1903–1995). Both programs were conspicuously anglophone, with minimal Québécois participation and only limited Indigenous and female representation.

At the time, military activity was not only highly masculinized but, in the first half of the twentieth century, the two world wars coincided with significant Indigenous suppression and evolving French Canadian nationalism. During the Second World War, efforts were made to identify francophone artists who might participate in the CWR, but with little success except for Albert Cloutier (1902–1965), who completed aircraft portraits such as Bluenose Squadron Lancaster X for Xotic Angel, 1945.

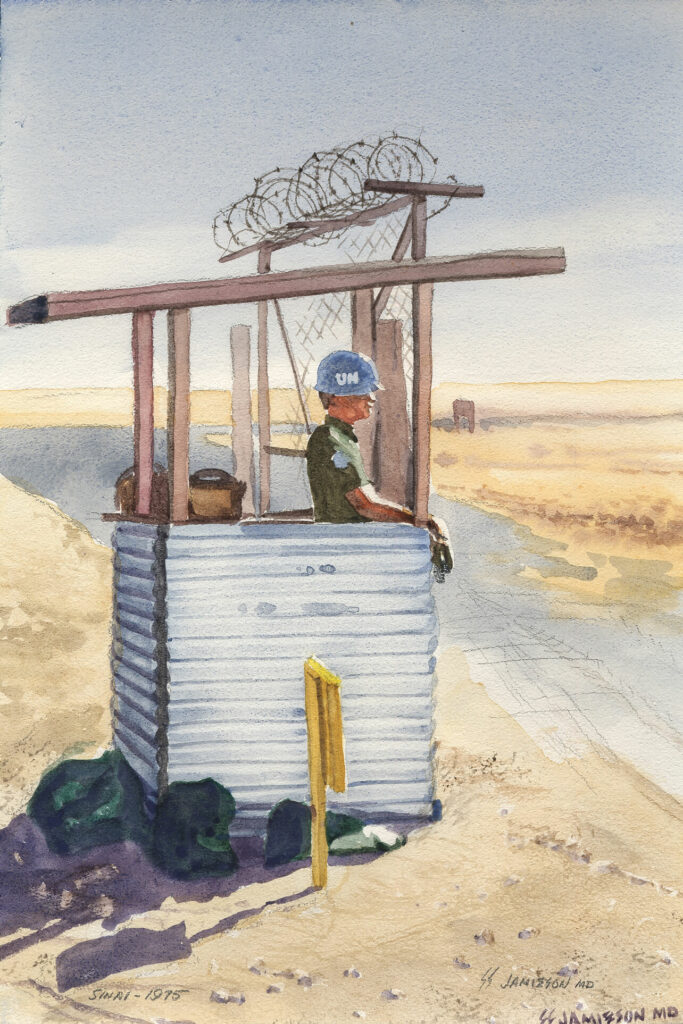

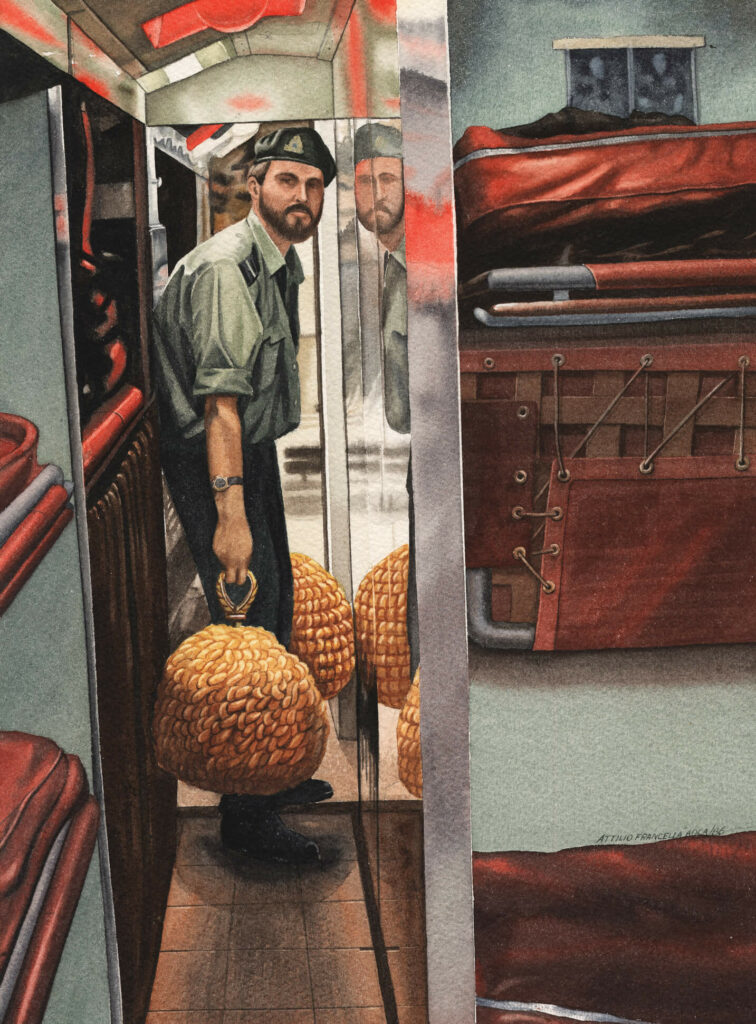

The Department of National Defence initiated the second pair of official military art programs, CAFCAP and CFAP, with ongoing input from national cultural agencies that include the National Gallery of Canada and the Canadian War Museum. Because of both schemes’ reliance on military cooperation, their art reflects military interests in their subject matter. CAFCAP art, so long associated with the Cold War, shows this focus—for example, Guard Post – Refuelling Stop – Sinai, 1975, by Geoffrey Jamieson (1931–2017), depicting a United Nations soldier in a tiny corrugated-iron hut in the seemingly empty Sinai Peninsula desert that forms the border between erstwhile enemies Israel and Egypt. Participating artists also recorded domestic military activities such as assisting with civilian emergency and with fire, flood, and storm management: Seaman with Fenders, 1985, by Attilio Francella (b.1948) is one such non-heroic work.

The current and more adventurous program, CFAP, is exemplified by The Expulsion (in white), 2013, by Mary Kavanagh (b.1965). Assigned to Defence Research and Development Canada (DRDC), she filmed the Radiological Analysis and Defence group engaged in radiation, biological, and chemical detection training. In this seemingly simple but complex and thoughtful double photographic portrait of two soldiers in highly protective clothing, Kavanagh, rather than displaying their soldierly qualities, emphasizes both the sophistication of twenty-first-century warfare and the vulnerability of its participants regardless of gender. CFAP also reflects Canada’s evolution into a multi-ethnic society. Kosovo-born painter Zeqirja Rexhepi (b.1955) introduced significant abstraction in his 2004 ceremonial paintings. Hong Kong–born photographer Ho Tam (b.1963) toyed with a romantic idea of the sea—in 2005 he photographed sailors on board a ship en route to Hawaii, giving their exchanges multiple meanings. The interactive My 8 Days as a War Artist, 2018, by Japanese Canadian video artist Midi Onodera (b.1961), resulted from a brief trip to Afghanistan in September 2010. Created over seven years and drawn from seemingly random material, her multilayered narrative based on memory, the unknown, and the imagined tries to make some sense of her military experience.

Creating the art was easier than finding a home for it. After the First World War, the official war art was supposed to be housed in a new Canadian war memorial art gallery in Ottawa, which was never built. Instead, until 1971, the National Gallery of Canada remained the custodian of the art of both the CWMF and the CWR. Since then, the Canadian War Museum, which dates to 1880, has held this responsibility, regularly adding to its current collection of artworks and organizing war art exhibitions. Under the aegis of the Department of National Defence, a network of seventy military museums in Canada, for the most part associated with Canadian regiments and housed in sometimes spectacular former drill halls such as that of The Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada regiment in Ottawa’s Cartier Square, also commission and collect art relating to specific regimental histories.

For most of the twentieth century, Canadian official war artists received a salary plus assistance with materials, accommodation, transportation, and studio space. The authorities vetted their work, suggested or ordered subjects, and determined the size and medium of each piece. The resulting artworks automatically entered the official war art collection, and, through their participation, many artists established their reputations.

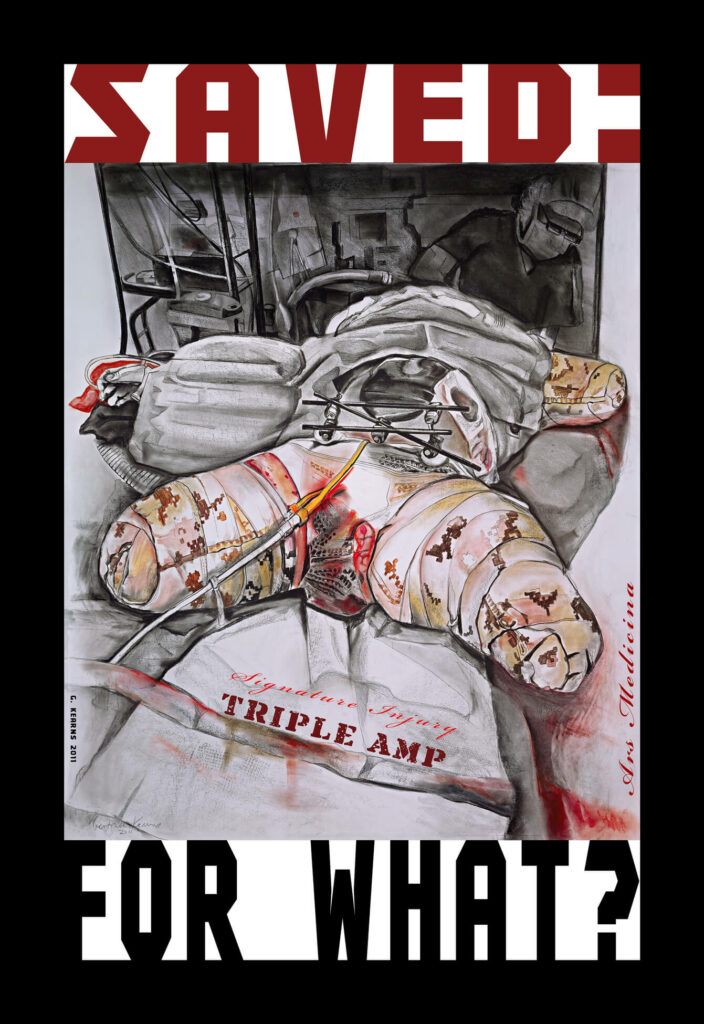

In the twenty-first century, this bargain no longer applies. The military provides CFAP artists with accommodation and transportation as well as a biannual opportunity to show work in exhibitions, but there are no long-term obligations or commitments. Supported by their dealers, some artists show independently with success, and a few sell their work. Most, however, donate their art to galleries and museums in exchange for gift tax receipts: few institutions will consider purchase, and the contemporary war art market is small. Elegiac landscapes referencing conflict achieve some success, as does the machinery of war, but explicitly violent and disturbing images from the battlefield find no home in Canadian public collections. One such example of a difficult image is Saved: For What?, 2011, by Gertrude Kearns (b.1950), depicting a seriously wounded triple-amputee soldier on a hospital bed.

Collection policies aside, all four official war art programs have in different ways curtailed artistic expression because, either physically or mentally, the artists were unable to operate independent of military infrastructures. Even for those opposed to war, most hesitate to create anti-war or protest art when surrounded by dedicated military personnel. Many choose to honour service―for instance, Karen Bailey documented the work of medical support staff at the Role 3 Hospital in Kandahar, Afghanistan, following her visit there in 2007. Furthermore, dealing with war’s main consequence—death—is problematic for artist and viewer alike, and always has been. Among the Canadian War Museum’s 13,000-work art collection, fewer than one hundred artworks show dead bodies. The record proves that we prefer to avoid depicting this darker side of our history in favour of ritualized mourning and remembrance—we reduce the dead to poppies and other symbols. Most of the countries allied with Canada in the world wars—the United Kingdom, Australia, South Africa, and New Zealand—have experienced variations of this pattern of engagement in their official war art.

The Impact of Exhibitions

Military-themed exhibitions traditionally celebrate achievements during conflict and remind the public of the huge contributions made by their families, communities, and country to the war or peacekeeping effort at home or abroad. Through visual displays with emotional impact, war art exhibitions can also serve educational, memorial, and propaganda purposes as they represent scenes of conflict and inspire national pride. They may even raise money through the sales of prints, posters, and catalogues. Most often they are facilitated by government agencies, including the Canadian War Museum, the National Gallery of Canada, Library and Archives Canada, and the Department of National Defence. Public reactions sometimes oppose institutional intentions. When the new pluralistic Canadian War Museum opened in 2005, some members of the public objected to the inclusion of a painting of a Canadian soldier convicted of a criminal act—The Dilemma of Kyle Brown: Paradox in the Beyond, 2001, by Gertrude Kearns.

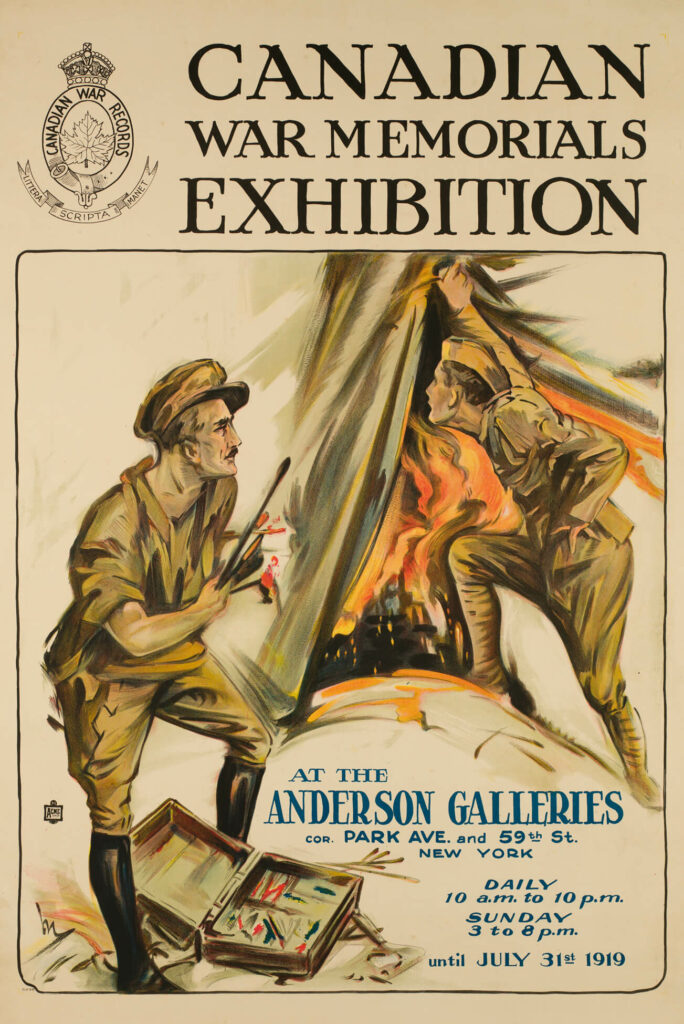

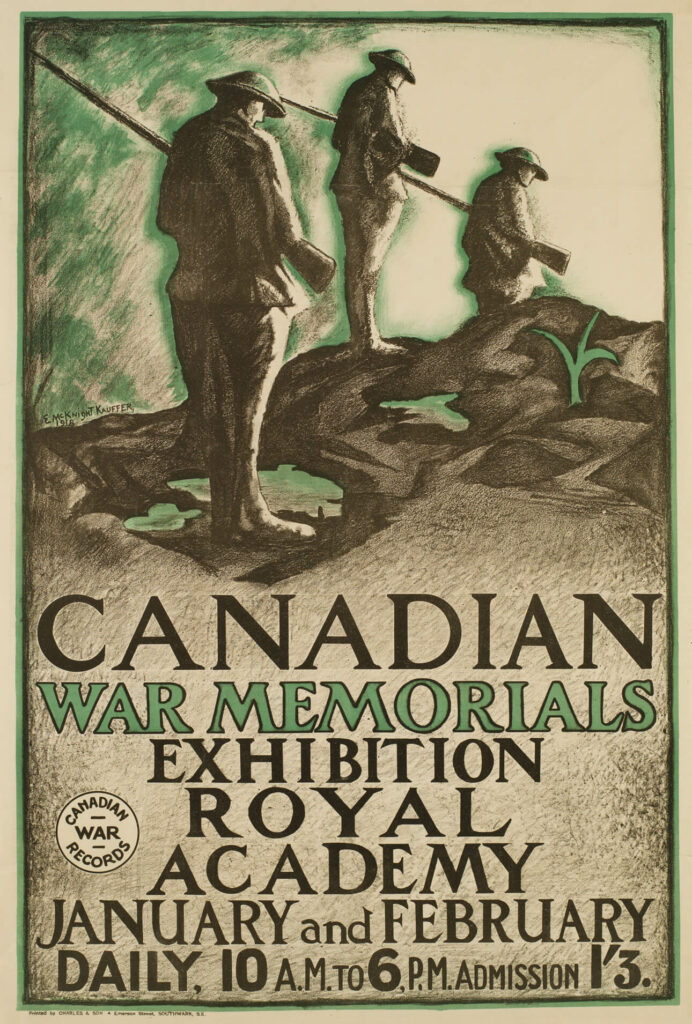

The realization, however, that exhibitions of Canadian military art could influence public opinion in favour of government actions dates back to the end of the First World War. In January 1919, the Canadian War Memorials Exhibition opened at the Royal Academy of Arts in London, England. The war had ended only eight weeks earlier, and some artists, such as Richard Jack (1866–1952), were still finishing their paintings at the academy in the days before the exhibition opened. The show travelled to the United States in July 1919, where New York’s Anderson Galleries hosted it, before moving on to Canada. In Britain the exhibition set a precedent with the sale and promotion of a catalogue (for one shilling), a limited edition of three hundred reproductions of twelve of the paintings, a lavish book titled Art and War (one pound, one shilling), and several editions of etchings, lithographs, and drypoints. Despite this notable marketing exercise, sales rapidly tapered off as the tragic legacies rather than the heroic achievements of the war were remembered.

In August 1920, the Canadian arm of the CWMF exhibited the second part of the program’s paintings at the Canadian National Exhibition in Toronto. Many of these works were by Canadian artists and dealt with the final phases of the war, “the triumphal entry of Canadian troops into the liberated cities and into German Rhineland, the surrender of the German Fleet, the Return of the Refugees to their devastated homes, and kindred subjects,” the catalogue stated. Again, this publication laid out where official war photographs could be purchased in Toronto and Montreal and listed prices for war etchings, drypoints, and lithographs by British and Canadian artists.

The available print list was extensive compared with its British predecessor and included works by C.W. Jefferys (1869–1951), with three lithographs; Arthur Lismer (1885–1969), with sixteen lithographs; and Dorothy Stevens (1888–1966), with six etchings, such as Munitions – Heavy Shells, c.1918. Further opportunities for commercial gain from print sales occurred in 1921, when the Imperial Order Daughters of Empire reproduced eighteen of the paintings for distribution to Canadian schools, including Canada’s Grand Armada Leaving Gaspé Bay, n.d., by Frederick Challener (1869–1959).

Other exhibitions of Canadian war art continued intermittently between the two world wars, usually tied to anniversaries. During the Second World War, serving Canadian artists including Will Ogilvie (1901–1989) participated in a number of exhibitions organized by the various services. These activities culminated in a major war art show at the National Gallery of Canada in 1946, which brought all the army artists together. In the postwar decades, two exhibitions toured to cities across Canada: A Terrible Beauty: The Art of Canada at War (curated by the Canadian War Museum and Heather Robertson in 1977) and Canadian Artists of the Second World War (curated by Joan Murray in 1981).

In the late 1990s, the Canadian War Museum organized the blockbuster exhibition (and accompanying book) Canvas of War: Masterpieces from the Canadian War Museum, which toured Canada between 1999 and 2004 and was seen by almost half a million visitors. Finally, in 2007 the museum broke the bias against women and war by organizing two exhibitions from a female perspective, War Brides: Portraits of an Era (an installation by Bev Tosh [b.1948]) and Stitches in Time (the work of Johnnene Maddison [b.1943]), both of which proved very popular with the public. The following year, the museum toured a selection of works from the CAFCAP and CFAP programs as A Brush with War: Military Art from Korea to Afghanistan. The Founders’ Gallery at the Military Museums in Calgary, Alberta, has hosted a number of thematic contemporary military art exhibitions to showcase the work of individual contemporary war artists, among them Dick Averns (b.1964), with War Art Now, 2010–11; Norman Takeuchi (b.1937), with A Measured Act, 2006; and Tosh, whose work on war brides (under the title here of One Way Passage, 2001) has also toured globally. Since 2015, a new series of exhibitions has promoted the work of the biennial groups of CFAP artists. Group 6 was exhibited at the Diefenbunker in Carp, Ontario, in 2015–16, and Groups 7 and 8, respectively, at the Canadian War Museum in 2018 and 2020.

The national institutions in Ottawa have organized the majority of these exhibitions by relying on the official collections and programs. As a result, in paint, print, sculpture, and photography, official art dominates Canadians’ knowledge of war art, while other visual expressions relating to conflict—protest art, for example—have been associated more with developments in contemporary art than with war art and have been shown in public institutions such as the National Gallery of Canada. The ongoing reputation and recognition of official war art is perhaps surprising, given that it has never had a long-term permanent display space.

Memorials and Tributes

Over the centuries, individuals, groups, and organizations have commissioned or created art to record their military achievements and defeats and to ensure they are remembered by future generations. Canadian memorials form part of the human rituals of mourning and help in forming identity.

Memorial art is scant for Indigenous peoples before the late nineteenth century. One of the best-preserved memorials is in Áísínai’pi, or Writing-on-Stone Provincial Park, in southern Alberta. This UNESCO World Heritage Site houses an extensive series of small-scale petroglyphs incised on the sandstone bluffs of the Milk River, a number dating to thousands of years ago. Some featuring men with guns, wagons, and horses show evidence of European contact. A complex, four-metre-long battle scene depicting a camp circle, mounted warriors, tipis, guns, and shot may depict an actual battle dating to the late 1880s—Retreat Up the Hill Battle (as described by an Aamsskáápipikáni elder named Bird Rattle in 1924).

In Western culture, memorials include specific monuments, such as the Joseph Brant Monument, 1886, erected seventy-nine years after Thayendanegea’s (Brant’s) death, as well as buildings, parks, schools, streets, and highways named after military heroes. Private memorials can be in the form of quilts, photograph albums, framed memorabilia, and the naming of children. There is hardly a community in Canada that does not have a memorial hall. Even Canadian geography plays a role, with hills, peaks, lakes, and other geographic features given new meaning through memorial naming.

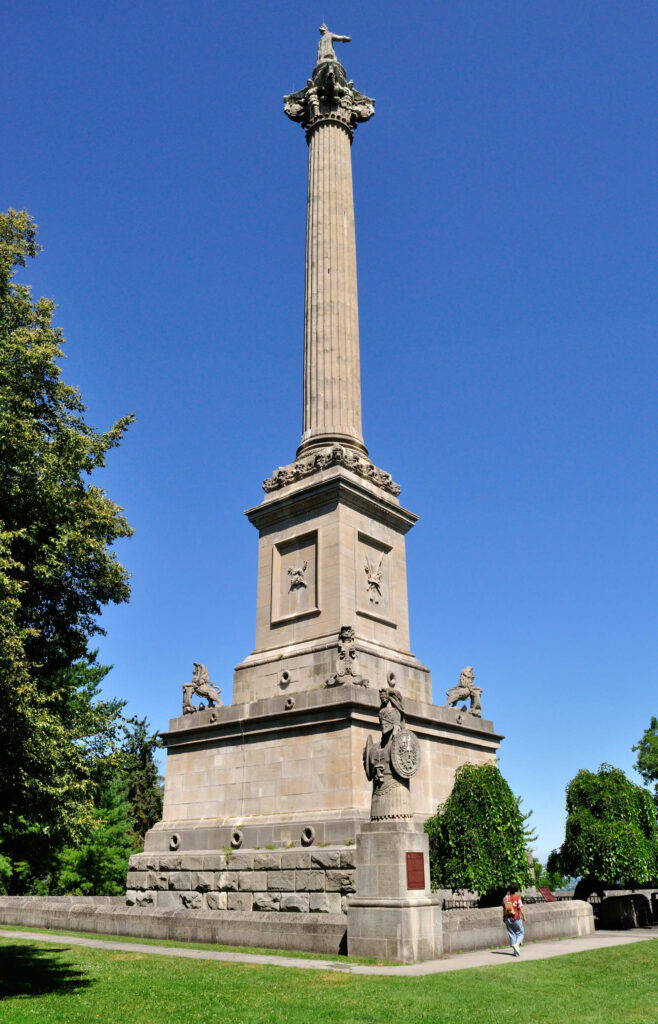

Before the twentieth century, Canadian memorials celebrated great leaders and victories, not the named deaths of ordinary service personnel. Brock’s Monument in Queenston, Ontario, for example, is dedicated to Sir Isaac Brock, the victorious general in the Battle of Queenston Heights during the War of 1812. First erected in 1824, it was blown up in 1840, presumably by an anti-British agitator. Ten thousand people gathered at the site to inaugurate a second memorial, unveiled in 1859.

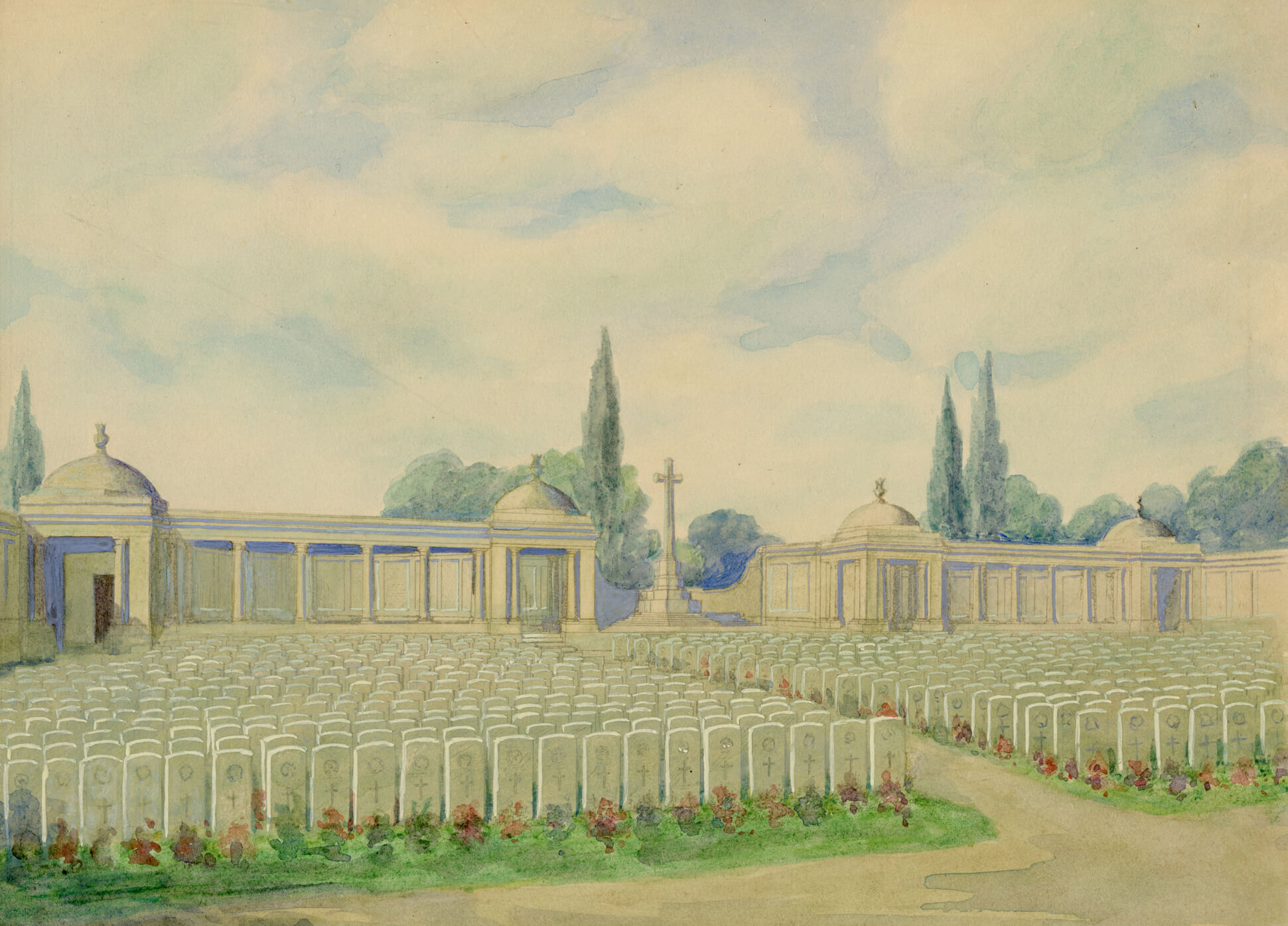

During the twentieth century, the First World War engendered a desire for a memorial on every possible battlefield and, in Canada, in every community, school, park, university, and department store, to cite some of the more obvious examples. The reason was simple: the dead never came home. Before the end of the First World War, the British authorities determined that soldiers should be buried where they fell and not repatriated. As a result, the much-visited but non-Canadian designed Commonwealth War Graves cemeteries situated on battle sites across the world are central to Canadians’ memories of twentieth-century war.

From Crete to Myanmar to Hong Kong and across Europe, it is possible to visit the graves of individual Canadian soldiers. As shown in the anonymouss painting Tyne Cot Cemetery (Passchendaele), c.1971 or earlier, the simple rectangular-shaped gravestones bear each soldier’s name, rank, and service unit and sometimes include a poignant family message. In the case of an aircraft that crashed, the gravestones of the dead who flew in it touch each other. In the case of unidentified bodies, the simple words “Known Unto God” adorn the marker.

The most famous overseas Canadian memorial commemorating a First World War military event is the Canadian National Vimy Memorial, 1921–36, by Walter S. Allward (1874–1955) on the site of the Easter 1917 Battle of Vimy Ridge, France. Another is The Brooding Soldier, 1923, by Frederick Clemesha (1876–1958) at St. Julien, Belgium, which commemorates the 1915 Second Battle of Ypres. Most of the major memorials in Canada, however, were imported as copies, especially from Italy. Only a few are associated with Canadian sculptors from that period—examples include Elizabeth Wyn Wood (1903–1966), who designed the Welland-Crowland War Memorial, 1939, and her husband, Emanuel Hahn (1881–1957), who designed the figurative war memorial at Westville, Nova Scotia, 1921.

The wealthy Drummond family’s personal memorial exemplifies private commemoration. Guy Drummond, son of Sir George Drummond, a former president of the Bank of Montreal, was killed at the Second Battle of Ypres in April 1915. The family commissioned Canadian doctor and sculptor Robert Tait McKenzie (1867–1938) to honour him with a small statue showing the upstanding young soldier in military uniform. It is now on display at the Canadian War Museum as an artifact of war rather than as a memorial.

Nurses and nursing associations from across Canada raised $32,000 to fund the Nurses’ Memorial, 1926, installed in the Centre Block, in the Hall of Honour, on Parliament Hill. Sculpted in marble by noted Montreal war memorial designer George William Hill (1862–1934), its allegorical figures underline the virtues of the nursing profession.

Stained-glass manufacturers such as the McCausland family, whose company was founded in Toronto in 1856 and is still active there five generations later, also created memorial windows. A series of twelve in the city hall of Kingston, Ontario, commemorates battles and groups that played a significant part in the conflict. Another art form, decorated honour rolls listing those who have fought and died in a community, became ubiquitous.

When the Second World War was declared, many of the First World War sculpted memorials had only just been finished, including the National War Memorial in Ottawa, 1926–32, designed by English sculptor Vernon March (1891–1930). Entitled The Response, 1925, the original model is displayed at the Canadian War Museum. In 1982, the dates of the Second World War and the Korean War were finally added to the finished memorial, and on November 11, 2014, it was rededicated to include the dates of the South African War, 1899–1902, and the Canadian mission in Afghanistan, 2001–14. The memorial is also the site of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, designed by Canadian sculptor Mary-Ann Liu (b.1958). In 2017, with public and government support, Landscape of Loss, Memory and Survival: The National Holocaust Monument, designed by Polish American architect Daniel Libeskind (b.1946) and Canadian landscape architect Claude Cormier (b.1960), was unveiled. In alluding to a broken hexagonal Star of David, a symbol of modern Jewish identity, it commemorates the six million Jewish men, women, and children murdered during the Holocaust and the millions of other victims of Nazi-era Germany and its collaborators.

The Cold War gave Canada a new memorial with Ottawa’s Reconciliation: The Peacekeeping Monument, 1992, designed by German Canadian landscape architect Cornelia H. Oberlander (b.1921), Canadian sculptor Jack K. Harman (1927–2001), and Jamaican-born Canadian architect Richard G. Henriquez (b.1963). To underline the monument’s reconciliatory message, broken walls rise to meet at a central point where three peacekeepers securely survey their surroundings. Harman’s model of the three figures is in the collection of the Canadian War Museum.

Medals also recognize and commemorate service rather than death. All Canadian soldiers receive them—usually more than one—but few have been of Canadian design. Official war artist Charles Comfort (1900–1994) designed the Canadian Volunteer Service Medal, which is granted to persons of any rank in the naval, military, or air forces of Canada who voluntarily served on active service from September 3, 1939, to March 1, 1947. His first design showing a sword circled by maple leaves was rejected in favour of the group of marching military personnel from all services that appears on the medal.

The Pearson Peace Medal was designed by Hungarian-born Canadian sculptor Dora De Pédery-Hunt (1913–2008) and first awarded in 1979. General E.L.M. Burns received it in 1981, in part for his work in nuclear disarmament. In recent decades, the Royal Canadian Mint has released a plethora of collectable commemorative coins relating to war that have also circulated. Military artist Elaine Goble (b.1956) designed the Year of the Veteran twenty-five cent coin in 2005 for the Mint.

Questions of Identity

Official war art is intended to project a national image—a country that has successfully participated in global military events and conflicts—whereas unofficial military art can represent many different goals, from representation to protest. Both influence current and future attitudes to conflict. Many members of the public at various times in history have regarded the production and display of war art as warmongering, while others take pride in the national achievements it represents. It can also represent loss and sacrifice, as in The Flag, 1918, by John Byam Liston Shaw (1872–1919), which shows a dead soldier holding Canada’s Red Ensign and surrounded by people grieving. Because military art is predominantly understood to be illustrative, the artists’ intentions are often ignored.

In recent years, the personal opinions of artists have emerged more clearly, as in Afghanistan #132A, 2002–7, by Allan Harding MacKay (b.1944). The title implies that this work is about Afghanistan and, because its creator was an official war artist, that the composition sheds light on Canadian military activity in that country and its peace-building goal. What we see in this drawing, however, is a young boy—likely Afghani judging by his clothing—walking past a series of blurred notices marked with maple-leaf symbols. We do not know what these notices say but they are clearly official. MacKay is encouraging us to ask ourselves what Canadians are doing in this part of Afghanistan, what meaning younger inhabitants take from the Canadian presence, and what this ambiguity means for Canadian identity.

Generally, however, war art is considered to be a unifying factor in Canada’s national identity—much as it is in Australia, New Zealand, Britain, and elsewhere. Before 1914, loyalty to Britain was an important element of Canadian distinctiveness as expressed in the Joseph Brant Monument, 1886. Loyalty to Britain was also a significant motivator in Canada’s participation in both the South African War and the First World War. At the same time, Britain’s apparent unwillingness to recognize the country’s significant manpower and home-front contributions and the success of its soldiers led to a determination in Canada, and also in other dominions, to achieve full independence. Each country’s pride in its achievements in war consolidated its fledgling sense of a separate national identity. In Canada, the 1917 Battle of Vimy Ridge, memorialized in the Canadian National Vimy Memorial, 1921–36, epitomizes this idea.

Until the First World War, there was no sense of Canadian distinctiveness in the nation’s war art. The Canadian War Memorials Fund employed only British artists until the National Gallery of Canada lobbied Lord Beaverbrook to include Canadian artists. A.Y. Jackson (1882–1974) was one of the first Canadians to paint overseas, and his moving A Copse, Evening, 1918, reflects his personal experience of war as a soldier. Following the Battle of Vimy Ridge in which the Canadian Corps distinguished itself, many more Canadian artists were appointed to record the war. In January 1919, the Royal Academy of Arts in London sponsored a large exhibition of Canadian war art to rapturous response. This first official program laid the seeds of three successive Canadian war art schemes.

When war broke out again in 1939, a new generation of Canadian artists, including Charles Comfort and Pegi Nicol MacLeod (1904–1949), lobbied for a second official war art program, which resulted in the Canadian War Records in January 1943. Its goal was to produce art documenting Canada’s contributions to the conflict and to support the country’s growing significance internationally. Comfort’s powerful work The Hitler Line, 1944, was inspired by his visit to a battle site during the Italian Campaign. He recorded in his diary: “One gun created a fantastic sight, sticking perpendicularly up into the air, like a gigantic pylon memorializing the disasters of war.” In the finished painting, the destroyed “panzerturm” (tank turret) is powerless as a group of grim-faced soldiers stride past it across the blood-red, broken-tree, and smoke-filled battlefield toward an unknown outcome.

After 1945, Canada rebranded itself as a peacekeeping nation. United Nations–sponsored missions dominated Canada’s military and diplomatic activities for the next four decades. The Canadian Armed Forces Civilian Artists Program, 1968–95, contributed approximately three hundred artworks by forty artists to the nation’s official war art collection. Soldier artists also created artworks. Peacekeepers, n.d., by Haitian Canadian Marc-Bernard Philippe (b.1959) depicts blue-helmeted peacekeepers interacting with Haitian children.

In the 1990s, Canada’s involvement in the First Gulf War, 1991, and the Yugoslav Wars, 1991–2001, combined with a series of important military anniversaries to reignite interest in Canada’s military past as a marker of identity. These anniversaries included the fiftieth anniversary of the end of the Second World War in 1995, the rededication of the Canadian National Vimy Memorial in 2007, and the ceremonies there on the one-hundredth anniversary of the Battle of Vimy Ridge in 2017. New battles and reminders of old wars reinforced the connections between art, war, and identity for Canadians.

The association between national identity and military involvement is captured today in the popular photographs of Silvia Pecota (b.1961), a Canadian Forces Artists Program participant. Many have been reproduced as prints, such as Fallen Comrades: Task Force Afghanistan, 2006, which contrasts and links an image of a Canadian flag–bedecked temporary memorial with fit, living soldiers.

Women Artists and Subjects

At most, only ten per cent of the Canadian War Museum’s art collection, which is largely of official origin, features women. The conduct of war is primarily viewed as a masculine activity, and this bias has skewed the art of war away from female subjects. Visit any military museum, attend any Remembrance Day service anywhere in the world, and the message will be that war is about men in combat. Furthermore, to fight a war requires promoting enlistment, honouring service, and recognizing past accomplishments, which are also, in the fighting context, primarily men’s activities. Consequently, conflict’s visual culture privileges the masculine subject and, inevitably, the male artist who, traditionally, has easier access to this subject matter. Weakness is rarely shown or depicted in this customarily hyper-masculine environment even though, today, approximately ten per cent of the personnel in Canada’s Armed Forces suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

As artists, women faced limitations that men did not. During the First World War, commissioned war artists such as English painters Anna Airy (1882–1964) and Laura Knight (1877–1970) worked on the home front, where, unusually, they painted men—in Airy’s Cookhouse, Witley Camp, 1918, for example, and Knight’s Physical Training at Witley Camp, c.1918. Curiously, only male commissioned artists appear to have painted women—invariably, nurses.

One notable example is the three-canvas triptych No. 3 General Hospital near Doullens, 1918, by English muralist Gerald Moira (1867–1959). In this painting of the interior of a church being used as a hospital in France, Moira depicts a nursing sister in the foreground looking over sick and injured military personnel. Soldiers often perceived nurses as “angels of mercy,” and the placement of the nurse below a small statue of the Virgin Mary and Jesus reinforces that message.

During the Second World War, female artists employed by the National Gallery of Canada painted servicewomen in Canada—Pegi Nicol MacLeod in Morning Parade, 1944, and Paraskeva Clark (1898–1986) in Parachute Riggers, 1947, for example. Among the thirty-two official Second World War artists working overseas and in Canada, only one was a woman, Molly Lamb Bobak (1920–2014). She created the compelling portrait Private Roy, 1946, as well as scenes of everyday army life, such as Inside the Auxiliary Service Canteen at Amersfoort, Holland, 1945. In contrast, male official war artists focused on the machinery and men of war.

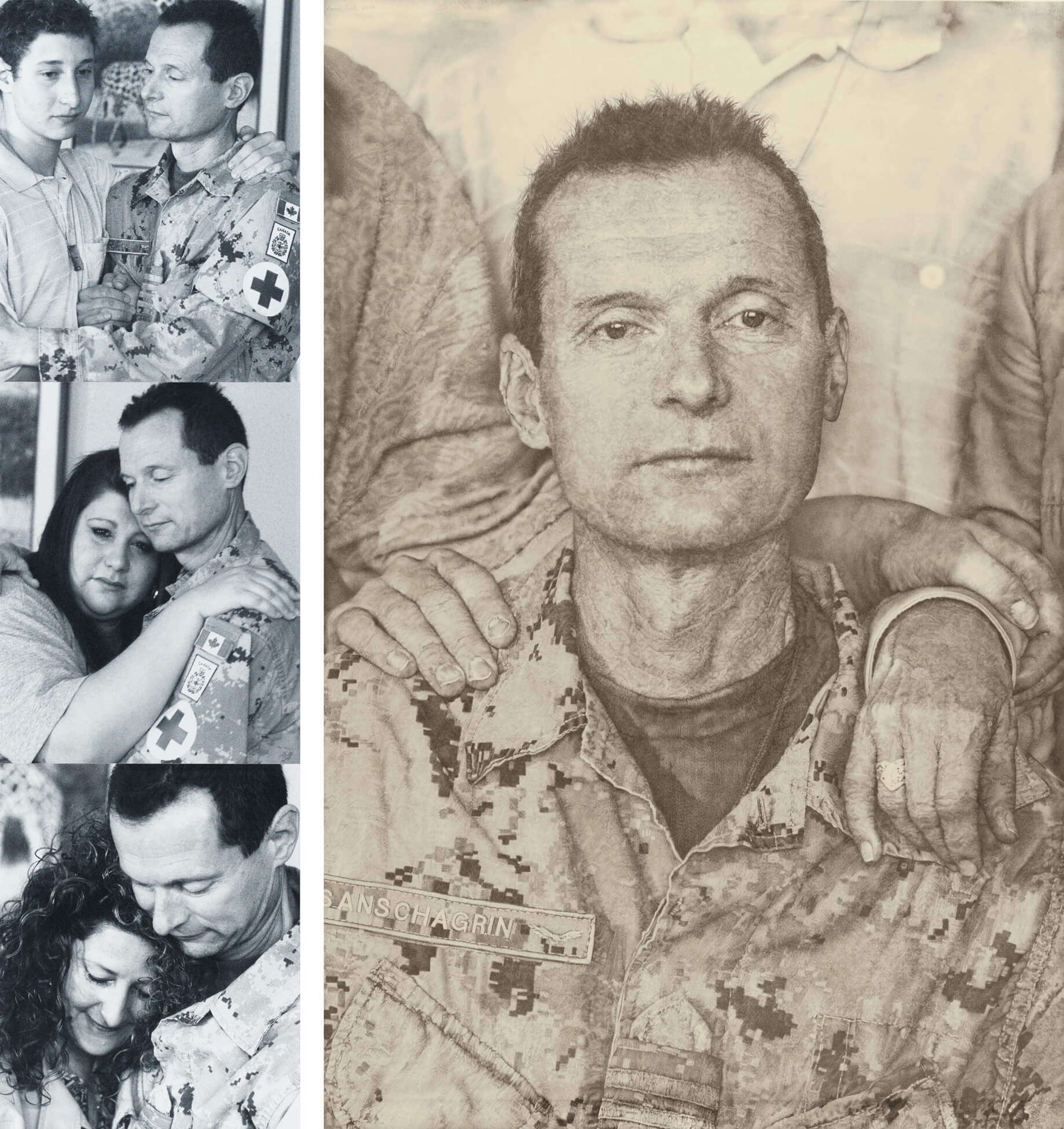

In recent years, artists such as Gertrude Kearns have made male soldiers the focus of their work—bringing the concept of the female gaze rather than the male gaze to war art. She has further widened the possibilities for women as war artists with portraits of herself in military uniform and depictions of her own traumatic experience during her assignment in Afghanistan, as in What They Gave, 2006. She is one of the few Canadian artists to have tackled severe war stress in art with her portrait Injured: PTSD, 2002—a commission from Veterans Affairs Canada intended to draw attention to the psychiatric condition and to humanize it. The painting’s subject elected to be anonymous, and the only clues to his situation lie in his wary glance, his clenched right hand, the stretcher to his left, and the title.

Another artist, Althea Thauberger (b.1970), has notably and somewhat controversially made women her subject—as in Kandahar International Airport, 2009. By presenting her armed female soldiers as carefree and smiling, she daringly invites criticism by providing a counter-image to prevailing public perceptions of military service in Afghanistan as having been a consistently serious business.

Increasingly, artistic crafts are being collected by and exhibited in museums and galleries. Through them, some unofficial Canadian women artists have produced stunning commentaries on the masculine nature of conflict. Barbara Todd (b.1952), for example, exhibited her quilt exhibition Security Blankets across Canada in 1992–95. Similarly outside any official program, Barb Hunt (b.1950), an interdisciplinary textile artist, knitted antipersonnel landmines in pink yarn to draw attention to the devastation of war. Her installation Antipersonnel, 1998–2003, consisting of several dozen replica landmines, draws on the history of knitting as caring for the body and the use of knitting to create bandages for soldiers. She contrasts this history with the destructive nature of the objects her artworks represent.

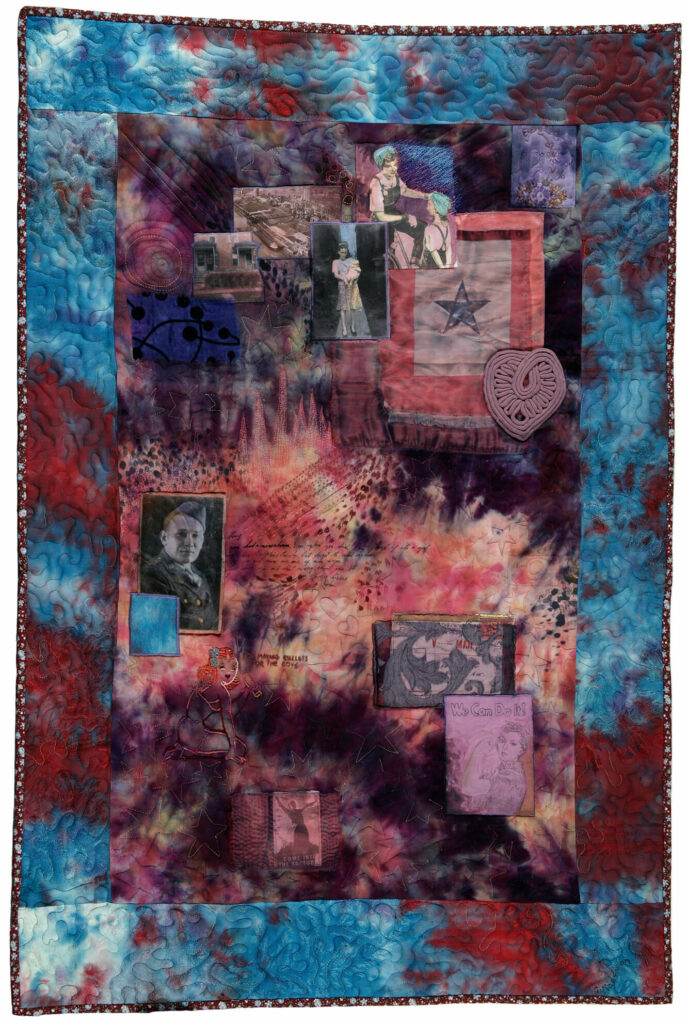

In 2007, two exhibitions organized by the Canadian War Museum demonstrated, through their visitor numbers and reception, that Canadian women’s stories in art and craft have substantial public appeal. War Brides: Portraits of an Era (featuring the work of Bev Tosh) attracted 85,000 visitors during its eight-month run. Stitches in Time (featuring the work of Johnnene Maddison) incorporated the crafts of quilting, embroidery, and transfer photography in a sewn memorial to women war workers in Canada.

The challenge going forward is how to increase the representation of women in the national war art collection. In recent years the number of female artists selected for the current official war artist program, the Canadian Forces Art Program (CFAP), has been almost equal to the number of men. Regardless, the environment in which these women will be immersed remains primarily masculine. Access to any military environment outside the official scheme is not easily done and requires imagination. Elaine Goble, who has never been a CFAP artist, provides one model: for nearly thirty years she has depicted the veterans and service personnel in her own neighbourhood to build up a body of work that focuses on the private impact of military experiences on children, wives, mothers, and families that she and they have rarely encountered except at a distance. In David’s Goodbye, 2008, for example, she drew and photographed the effect of PTSD on a particular family.

Indigenous Representation

Much early Indigenous conflict-related art—weapons and clothing, for example—has been studied ethnologically and ethnographically. As such, it has been viewed as an expression of particular cultures and peoples rather than as fine art. The few surviving objects of pre-contact, conflict-related visual achievements have not featured significantly in the country’s military art history.

In the First World War, the 4,000 members of the Canadian Expeditionary Force who were of Indigenous descent were virtually ignored in war art, as were the 3,000 Indigenous peoples in Canada who enlisted during the Second World War. In the late 1990s, research for the travelling Canadian War Museum exhibition, Canvas of War: Masterpieces from the Canadian War Museum, led to the identification of a Métis Second World War soldier represented by Australian-born artist Henry Lamb (1883–1960). The original title of the painting, A Redskin in the Royal Canadian Artillery, has now been replaced by Trooper Lloyd George Moore, RCA, 1942.

The beginning of the twenty-first century has witnessed increasing numbers of artworks by Indigenous artists. The National Aboriginal Veterans Monument in Ottawa, created by Noel Lloyd Pinay (b.1955) of the Peepeekisis First Nation in Saskatchewan in 2001, is richly symbolic. Frequent use is made of the circle and the number four, which have spiritual importance. Four figures (two men and two women) represent Indigenous peoples in Canada, including the Inuit and the Métis. Two of the figures hold weapons, and two hold spiritual objects. An eagle occupies the highest point of the sculpture. It symbolizes the Creator or Thunderbird and embodies the Indigenous spirit. The four animals below—wolf, grizzly bear, buffalo, and caribou—represent spiritual guides.

More recently, a significant number of Indigenous artists have participated in the Canadian Forces Artists Program. They include Inuit carver Tony Atsanilk (b.1960) and Métis photographer Rosalie Favell (b.1958), who in 2017 were involved in Operation Nanook in Rankin Inlet, Nunavut, when nine hundred military and civilian participants took part in Canada’s annual Northern sovereignty operation. Earlier, in Rangers, 2010, a special commission for CFAP, Kinngait (Cape Dorset) artist Tim Pitsiulak (1967–2016) depicted the Canadian Rangers, of which he was a member, unloading boats. In 2015 Métis artist Eric Walker (b.1957) revisited his father’s wartime naval experiences in Halifax in video (The View from Point Pleasant, 2017) and installation.

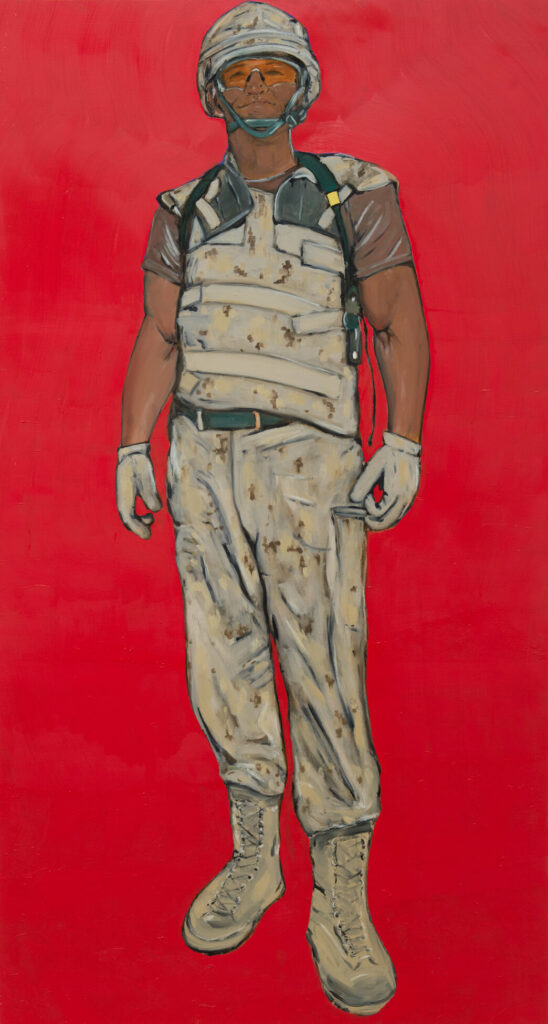

Visual and performance artist Adrian Stimson (b.1964), a member of the Siksika (Blackfoot) Nation in southern Alberta, was stationed at Forward Operating Base Ma`sum Ghar in Kandahar, Afghanistan, in 2010. His two full-length portraits of Indigenous soldiers, Master Corporal Jamie Gillman 2010 and Corporal Percy Beddard 2010, both 2011–12, set against a blood-red background, raise questions as to whether they are portraits of the living or memorials to the dead. A shelf containing handfuls of emblematic cedar, sage, sweetgrass, and tobacco joins the two portraits. His work on memory and the First World War also inspired his performance, Trench, 2017, which involved digging a trench and recreating images drawn on a war exploit robe, The “Great War” Deeds of Miistatosomitai (Mike Mountain Horse) (1888–1964), n.d., by Eskimarwotome (Ambrose Two Chiefs) (c.1891–1967). Indigenous artists regularly reference their own spiritual practices in their work. Stimson’s trench, for example, emphasizes the hard work essential to spiritual healing.

Propaganda Materials

Propaganda Materials

Propaganda is the organized dissemination of information to influence thoughts, beliefs, feelings, and actions. In war, its goal is to encourage citizens to make sacrifices and contributions to hasten victory or endure defeat. Media used to ensure such desired results include all those associated with war art, including film, painting, photography, and posters.

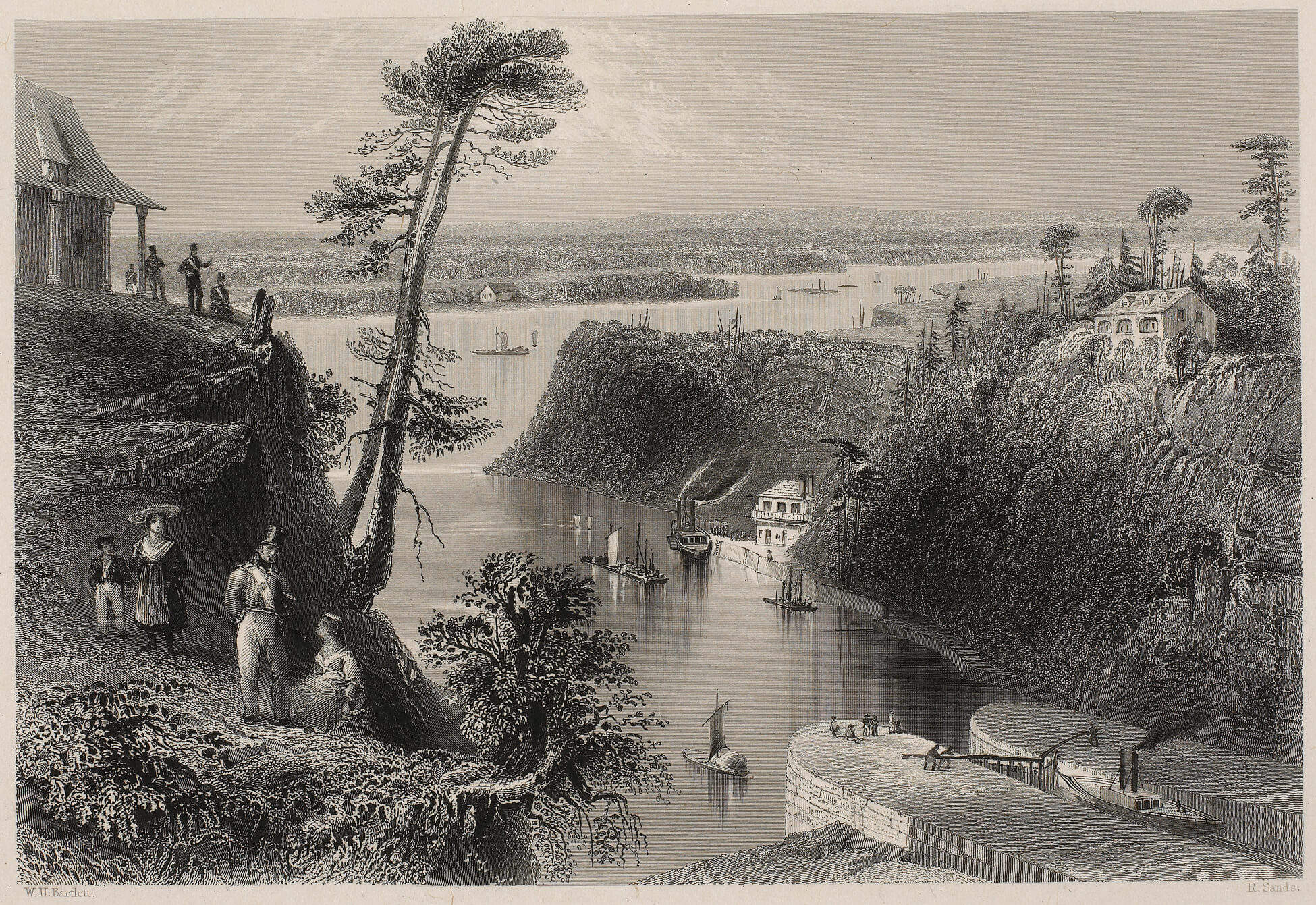

Before the First World War, propaganda in Canada was largely the purview of painting and its print reproductions. In the nineteenth century, widely circulated prints by artists such as W.H. Bartlett (1809–1854), while not overtly designed to be propaganda, did much to reassure would-be immigrants to Canada that the country was securely garrisoned. His print The Rideau Canal, Bytown, 1841, with its ordered scenery and prominent but relaxed foreground officer, is a typical example. The Rideau Canal had been built to provide an alternative protected route for British garrisoned troops to the American-guarded Saint Lawrence River.

Propaganda became a professional business during the First World War. Lectures, news articles, and cartoons vilified the enemy and persuaded citizens to part with their cash as well as their children to help wage war. During the conflict, a majority of the propaganda material used in Canada originated in Britain. Canada was part of the British Empire fighting an Imperial war, and the mother country tended to supply what was needed, including artists.

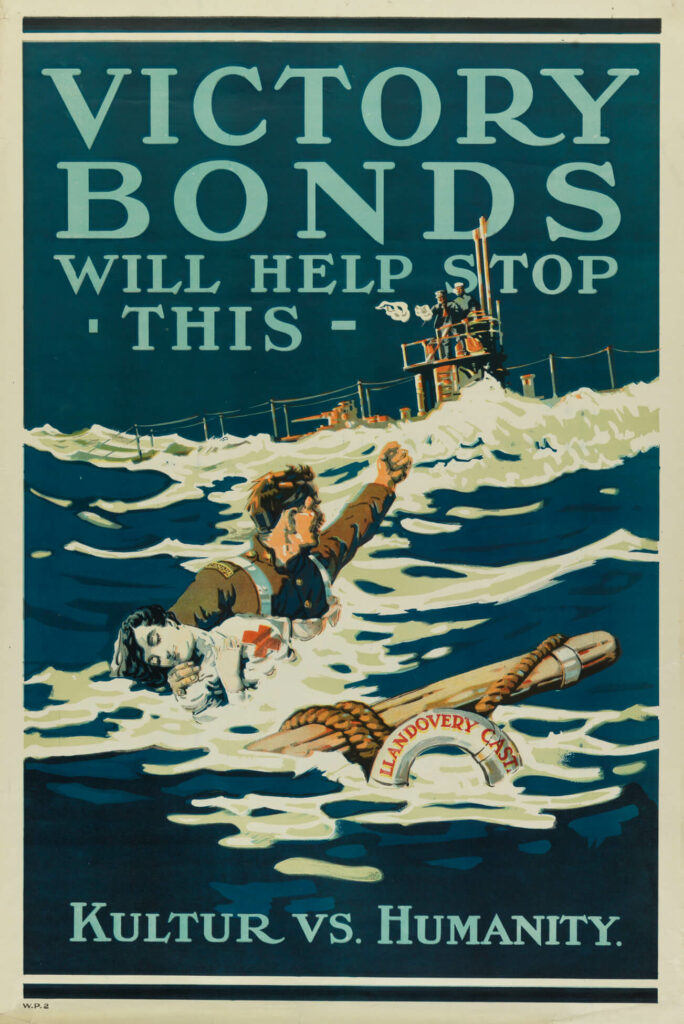

Canadian posters of note focused on raising money in support of the war through Victory Bonds. For Industrial Expansion, Buy Victory Bonds, c.1917, by Canadian graphic designer Arthur Keelor (1890–1953) exemplifies this direction. The poster Victory Bonds Will Help Stop This – Kultur vs. Humanity, 1918, was particularly effective as it played on the outrage sparked by the 1918 torpedoing of a hospital ship, the HMHS Llandovery Castle, which resulted in ninety-four Canadian medical officers and nurses being killed. The image is pure propaganda, with the soldier shaking his fist at the German submarine, a drowned nurse in his arms. On the poster, Germany, encapsulated in the word “Kultur,” which represented all that was bad about the country, is put in direct opposition to the word “Humanity,” the clearly delineated Allied virtue. The purchase of Victory Bonds, it is suggested in the poster’s other wording, will help stop this sort of tragedy.

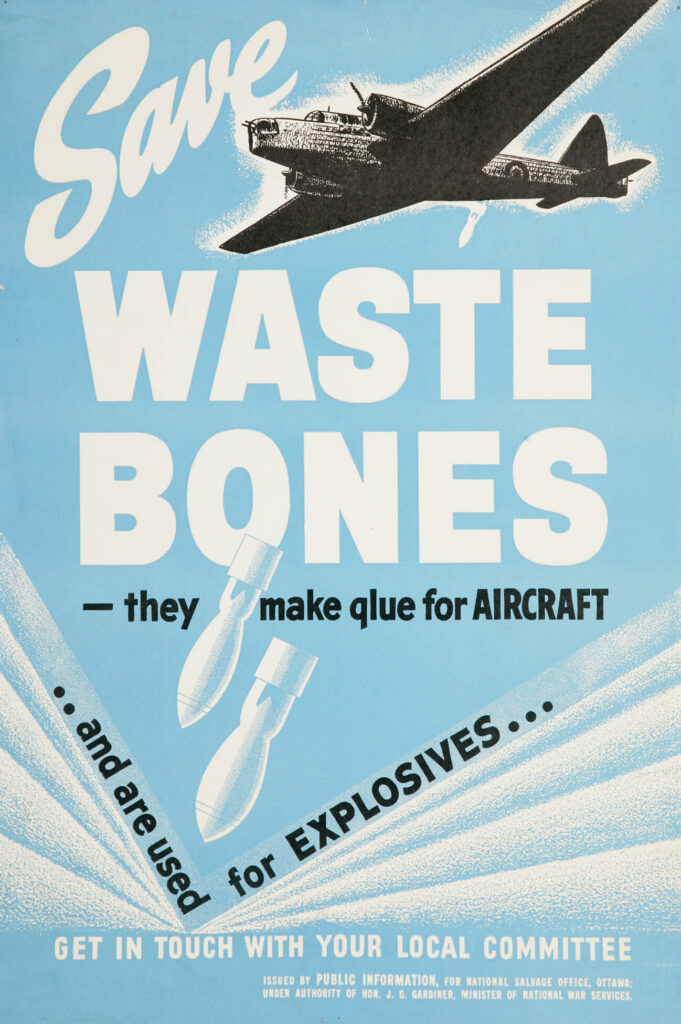

During the Second World War, after a slow start, Canada’s new Wartime Information Board saturated the country with some seven hundred propaganda poster designs for use on billboards, buses, streetcars, and even matchboxes, as well as in shop windows and theatres. Save Waste Bones – They Make Glue for Aircraft… And Are Used for Explosives, 1940–41, encouraged Canadians to reuse and recycle so that salvaged material could be turned into war material—such as the glue for aircraft like the Wellington bomber that forms part of this poster’s design.

The infant in the undated poster Invest and Protect. Help Finish the Job resembles the iconic Gerber Baby, adopted as the food company’s official trademark in 1931. The poster speaks to the same qualities used to sell baby food and to the values Canadians had to protect, including home, family, and their children’s future. The outline map of Canada in the background reinforces the notion that all Canadians had to contribute to end the war. Although it is difficult to gauge the direct impact of these posters, the nine Second World War Victory Loan campaigns raised more than $12 billion in support of the war.

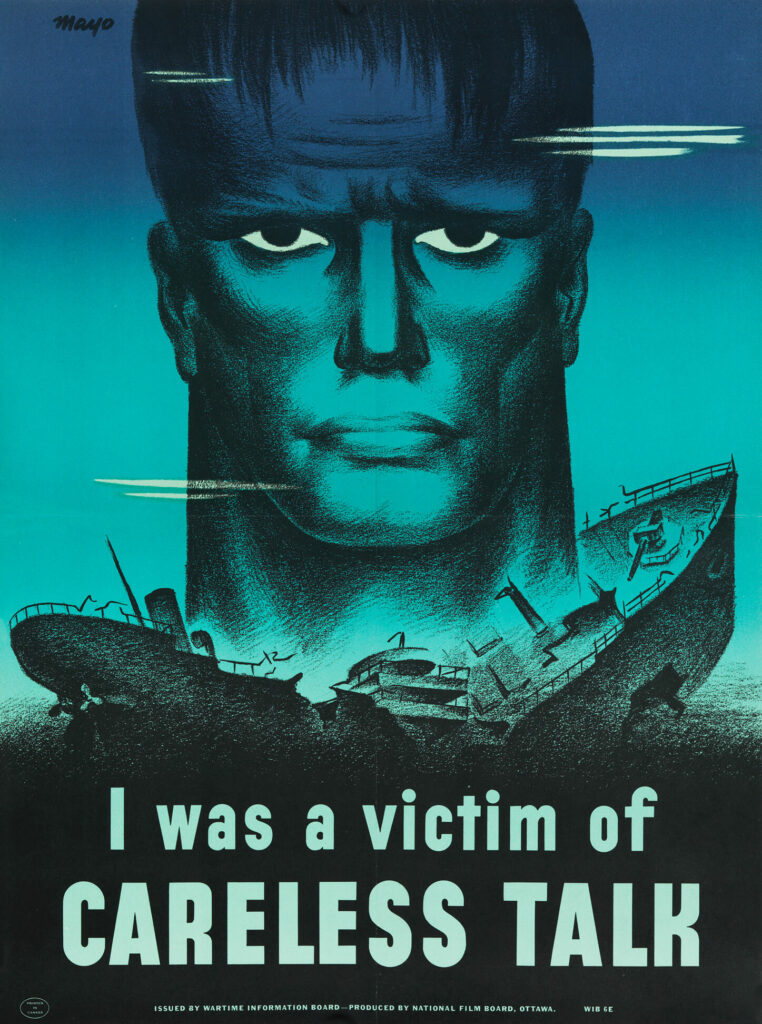

The National Film Board (NFB) proved to be an effective propaganda machine as well with its films and posters—for example, I was a Victim of Careless Talk, 1943, by Harry “Mayo” Mayerovitch (1910–2004), which extolled discretion among civilians. Soft propaganda included the NFB’s Canada Carries On series. Shown in eight hundred movie theatres across Canada, the series was created as a tool to showcase Canada’s wartime achievements. Columbia Pictures distributed a new film every month. The first film in the series was Atlantic Patrol, released in April 1940, about the Royal Canadian Navy’s role in protecting convoys from Halifax to the United Kingdom from U-boat attack.

In the current era of fake news, social networks, and general online use, it is more challenging to recognize propaganda for what it is. The series of thirty-four text-rich military portrait posters from Gertrude Kearns that reference Canada’s role in Afghanistan draws attention to what we see, accept, or reject in war images in intriguing ways. In works such as Science of War (Lieutenant-General Andrew Leslie), 2013, her subjects are all drawn and painted from life. The resulting posters consist of the finished portrait, overlaid quotes she gleaned from the subject during interviews, and other text she collected during her research. All the subjects have approved the final works, even though the verbatim texts could be controversial. Although flattery was not the artist’s intention, the portraits are generally pleasing—a by-product, likely, of Kearns’s immersion in a military culture whose own propaganda promotes masculine values relating to strength, power, and appearance.

Protest and Activism

Protest art tends to be ephemeral and is seldom safeguarded in national collections. Though Canada was not directly involved in the Vietnam War, 1955–75, it ushered in an era of global protest and brought thousands of war resisters to live in Canada. Televised images of the conflict’s atrocities brought the war vividly into Canadian lives. Roused by what they had seen, large crowds joined in street demonstrations, as shown in the 1969 photograph by Toronto Star photojournalist Reg Innell (c.1925–2018) of exhausted protesters surrounded by piles of handmade signs beside the war memorial in Toronto. Even so, the few examples of Canadian protest art related to that war received little public attention. The mural Homage to the R 34, 1967–68, by Greg Curnoe (1936–1992) hung in Montreal’s Dorval airport for only eight days before being put into storage, while the film Rat Life and Diet in North America, 1968, by Joyce Wieland (1931–1998) was virtually ignored at the time.

Before the 1980s, only a few examples of Canadian protest art related to war. Hardly any visual materials were created to protest the conscription crises during the First and the Second World Wars, as well as the imposition of the War Measures Act in October 1970 following the kidnapping and murder of Quebec cabinet minister Pierre Laporte. After 1945, Canadians tended to view themselves as peacemakers rather than warmongers, and this attitude probably contributed to the vacuum in protest art.

This quasi-complacency changed with the government’s decision to support the testing of cruise missiles over Canadian soil in the early 1980s and motivated one of the largest bodies of protest art in Canada—the widely exhibited Art of War series by Nova Scotia artist Geoff Butler (b.1945). Butler worked on the paintings for eight years and, in 1990, published the images as a book, Art of War: Painting It Out of the Picture. One composition, Happy Days Are Here Again, 1983, shows a massively injured community in the aftermath of a nuclear attack. The figures are blood-red as they enter and leave a hospital tent, a few sticking plasters the only relief for their excoriated bodies. As these near-corpses pick their way past a cemetery, nothing living around them has survived. The powerful drawing Second Strike, 1981, by John Scott (b.1950) also responds to cruise missile testing.

Because… there was and there wasn’t a city of Baghdad, 1991, by Lebanese Canadian Jamelie Hassan (b.1948) bridges past and present experiences in the First Gulf War, one in which Canada participated. Based on a photograph of the Haydar-Khana Mosque in Baghdad, Iraq, taken during a study trip in the late 1970s, her billboard, conceived in response to the 1991 conflict, overlays this image with the words that are its title. The implication is that, thanks to intensive bombing, Baghdad is no longer the city it was.

A number of protests in the 1990s were responses to Indigenous peoples’ loss of their land. In the summer of 1990, during the Oka Crisis, many protests broke out in support of the Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk) Nation of Kanehsatake in their struggle to maintain their Quebec territory. The following year, Anishinaabe performance artist Rebecca Belmore (b.1960) created an installation resembling a large wooden megaphone through which the Indigenous voice could be amplified to express its land ownership more potently. Entitled Ayum-ee-aawach Oomama-mowan: Speaking to Their Mother, 1991, it travelled to many Indigenous communities. In 1991, Kanien’kehá:ka artist Shelley Niro (b.1954) photographed her sisters in contemporary dress beside the Joseph Brant Monument, 1886, as part of her Mohawks in Beehives series. She wanted to make the point that Indigenous culture in Canada is not just historical but contemporary, and that it cannot be held ransom to past assimilative practices. In so doing, she reclaimed a space from which a real Indigenous presence had been erased.

Error, 1993, by Allan Harding MacKay represents an act of protest—it is one of only three images from his Somalia series that he did not deliberately destroy to register his disapproval of Canada’s active involvement in the bombing of Kosovo in the former Yugoslavia in 1999. He has never ceased protesting through his military art. In 2012, Andrew Wright (b.1971), a participant in the Canadian Forces Artists Program, photographed MacKay on Parliament Hill just before he tore up one of his Afghanistan works to protest the Harper government’s treatment of veterans and Indigenous peoples.

Jayce Salloum (b.1958), a Lebanese Syrian Canadian winner of the Governor General’s Media and Visual Arts Award, and Iraqi Canadian Farouk Kaspaules (b.1950) believe the political nature of their artworks contributed to the temporary cancellation of the exhibition The Lands within Me at the Canadian Museum of History in fall 2001. The exhibition showcased the art of twenty-six Canadians of Arab origin and was set to open in October 2001, shortly after the September 11 attack on the World Trade Center in New York (9/11). The museum’s decision to postpone the exhibition’s opening invoked outrage in Canada’s Muslim community, which believed the decision associated them with the terrorist action. Under pressure from Prime Minister Jean Chrétien, the exhibition opened on time.

A more recent work, Not Elsewhere, 2019, by Sanaz Mazinani (b.1978), an Iranian Canadian installation artist, consists of three immensely long fabric sheets that appear to replicate on their surfaces the Islamic motifs incorporated into the Aga Khan Museum in Toronto, for which it was created. In fact, the images are of contemporary military aircraft used in Middle East conflicts.

Representing Violence

Of the approximately 13,000 artworks in the custody of the Canadian War Museum, fewer than one hundred directly depict violent death. Similarly, very few depict fighting. Except in the form of ruined buildings (especially churches), broken trees, and allegorical figures representing the virtues and consequences of war, traditionally explicit violence is rarely a subject for war artists and photographers. For the most part, if governments have their country’s support in waging war, artists tend not to focus on conflict’s more distressing aspects. Official artists in particular feel they are part of the war effort and that their task is to maintain morale and not destroy it.

During the First World War, soldiers could not carry cameras after 1915, and the official photographers could photograph only the enemy dead. Given this restriction, words alone could give meaning to otherwise innocent images. A 1917 image attributed to English official Canadian photographer William Castle (1877–1947) shows two officers looking at some felled trees. Nothing indicates who chopped them down or why, but the text that accompanied the image when it was exhibited a few months later gave it the veneer of terrible tragedy: “The wanton destruction of these trees can only be stigmatised as ‘murder.’ To prevent their being of any use to the advancing troops, the Germans took the life of each one by severing its trunk.” In the prevailing Christian context of the time, trees symbolized life lived in accordance with God’s plan; the tree’s annual cycle refers to life, death, and resurrection. In this context, the trees stand in for dead soldiers who could not be depicted in any other way. The Sunken Road, 1919, one of the most violent war images by Frederick Varley (1881–1969), is based on a Canadian official wartime photograph of dead Germans. He used the same photograph in German Prisoners, c.1919.

In the Second World War, although artists were equipped with cameras, most were loath to make their images public. The photographs taken by Alex Colville (1920–2013) at the Nazi concentration camp of Bergen-Belsen in 1945 were not seen until after his death in 2013, and they have not yet been exhibited. One of his most important paintings, Bodies in a Grave, 1946, is, however, directly related to these photographs.

To depict violence, Jack Nichols (1921–2009) did not rely on his camera. Drowning Sailor, 1946, the most visceral depiction of dying in the Canadian War Museum’s art collection, is based on his personal memory of watching a German sailor drown in front of him after the man’s ship was torpedoed at sea. Nichols was on board HMCS Iroquois, which later picked up survivors and brought them on deck. Nichols painted these acts of humanity as well, in Taking Survivors on Board, 1945. He would return to these experiences late in life, creating the work Torpedoed Ship, 1995.

Contemporary artists—usually unofficial—have been no less reluctant to confront war’s violence. One exception is What They Gave, 2006, by Gertrude Kearns, a portrait of three badly wounded men (two soldiers and a young Afghani civilian). Her Saved: For What?, 2011, is even more disturbing, an art print based on a photograph depicting a bloodied, bandaged triple-amputee. It speaks directly to For What?, 1918, by Varley, and, to date, it is the most explicitly violent image about war in Canadian art history. With this vicious image, Kearns unflinchingly turns the tables on male attitudes to violence. For war art to be a true record of human conflict, Kearns suggests, we must look less symbolically at the violence that enemy nations mete out to each other.

Connections to Religion

On permanent display in the Canadian War Museum’s Regeneration Hall, alongside the plaster models for the figures on the Canadian National Vimy Memorial, 1921–36, by Walter S. Allward is a massive painting of the crucified Christ hanging dead in front of a First World War battlefield. Sacrifice, c.1919, was commissioned from English artist Charles Sims (1873–1928) to hang in the never-built Canadian War Memorial art gallery in Ottawa—the last image seen by visitors to the commemorative space before they departed. One hundred years later, it still packs a powerful punch and, moreover, shows that even in an increasingly secular society like Canada, the mix of war and religion is potent.

Christian iconography, with its language of violent sacrifice, is a constant thread running through military visual culture. No other spiritual practice in Canada—Indigenous, Muslim, or Jewish, for example—has had such an effect on historical Canadian war art. In twenty-first-century war art—and in a secular world—this impact is largely gone, but Christianity’s role in creating the visual language of war over centuries is enormous. The most famous painting in the National Gallery of Canada, The Death of General Wolfe, 1770, by Benjamin West (1738–1820), evokes in its compositional structure myriad depositions of Christ familiar to art history.

After the outbreak of the First World War, as the casualty numbers began to rise, Christian religious practice revived and translated into war art. This revived religious sensibility assisted both the wartime church and the government in justifying the killing involved in war, allowing them to rationalize the conflict. Later, as the body count grew, authorities could equate a soldier’s death in battle and the grief at home with Christ’s agony on the cross and his mother’s sorrow. Throughout the war, crucifixion images conveyed the idea that the slaughter was not senseless but redemptive. This trend is highly visible in the Canadian National Vimy Memorial, which is essentially a buried cross, the figure of Sacrifice between two pylons equating with the crucified Christ.

During the Second World War, Jewish-born Jack Nichols used Christian imagery in his works, channelling the power of European masterpieces he had seen in the Louvre, Paris. Taking Survivors on Board, 1945, also recalls images of Christ’s deposition, with the wounded Jesus figure spreadeagled mid-composition and the mourners around him. The composition’s association with the centuries-old visual vocabulary of Christianity intensifies the emotions of sorrow, fear, concern, and loss.

Neither Christian nor Jewish symbolism is readily apparent in the Second World War work of other Jewish artists, including Aba Bayefsky (1923–2001), Louis Muhlstock (1904–2001), Harry Mayerovitch, Ghitta Caiserman-Roth (1923–2005), or Moses “Moe” Reinblatt (1917–1979). However, the Star of David, the modern symbol of Jewishness, is prominent on the graves of Jewish soldiers throughout the Commonwealth, as well as at Landscape of Loss, Memory and Survival: The National Holocaust Monument, Ottawa, 2017.

It is impossible to identify religious symbolism that equates in any way with its First World War flowering when perusing the war and military art that has come out of CAFCAP and CFAP. Yet religion is still very much part of Canada’s military. The Canadian Armed Forces has approximately 190 Regular Force chaplains and 145 Reserve Force chaplains representing the Christian, Muslim, and Jewish faiths. Canada’s military regiments hang their colours in churches, where they rest until they rot away. Remembrance Day services involve hymns and prayers. Indeed, prominent in the Royal Canadian Legion’s Remembrance Day website is the injunction “Remembrance Day is a day for all Canadians to remember the men and women who served and sacrificed for our country.”

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements