Walter S. Allward (1874–1955) was active when there were only a few sculptors in Canada. His success inspired other young artists, including Emanuel Hahn, Frances Loring, Florence Wyle, and Elizabeth Wyn Wood, all of whom went on to make significant contributions to Canadian art. Allward’s various war monuments, culminating in the Vimy Memorial, had a moral as well as an aesthetic purpose, and were markedly different from those of both the previous generation of sculptors and those of his peers. His intention was to reveal the tragedy of war and design monuments that more provocatively explored themes of redemption.

Memorializing the First World War

Although the depiction and commemoration of war is present throughout history, the First World War (1914–1918) engaged artists to an extent greater than any other previous conflict. The participation of artists from Canada was mainly due to the efforts of William Maxwell Aitken, the future Lord Beaverbrook, who, in November 1916, established the country’s first official war art program, the Canadian War Memorials Fund. The fund was intended to provide an enduring record of the war effort both in Canada and abroad, and would eventually employ more than one hundred artists (mostly British and Canadian). By the end of hostilities, artists including Cyril Henry Barraud (1877–1965), John William Beatty (1869–1941), Richard Jack (1866–1952), Mabel May (1877–1971), and Alfred Munnings (1878–1959), along with future members of the Group of Seven A.Y. Jackson (1882–1974), Arthur Lismer (1885–1969), and Frederick Varley (1881–1969), would create almost one thousand artworks.

Although the collection was exhibited to great fanfare at Burlington House in London in early 1919 and later toured North America, Aitken’s plan to house the works in a war memorial gallery in Ottawa was subsequently abandoned as the country’s attention shifted from documenting battles to memorializing those who had died in the conflict. The fund had been successful in chronicling Canadian soldiers’ experiences, but a deeper response to the tragic loss of more than 61,000 lives was expressed through commemorative monuments, which, in the words of the historian Robert Shipley, “were part of the attempt to make sense on an emotional and spiritual level of the loss of so many friends, loved ones, and comrades.” More than seven thousand memorials were erected in communities across Canada following the war, most of which were funded by local residents. Usually set in a central location, they were produced in a variety of forms, ranging from simple crosses on pedestals, as in the town of Trochu, Alberta, to the elaborate Soldiers’ Tower at Hart House, University of Toronto.

Approximately four hundred memorials in Canada include figures, most portraying soldiers in uniform, either alone or in groups. The most ambitious is the National War Memorial in Confederation Square, Ottawa, 1925–39, which consists of a large granite arch with twenty-two figures of men and women representing the various military services that contributed to Canada’s war effort between 1914 and 1918. The vast majority of memorials were modest in comparison. George W. Hill (1862–1934) was the most prolific designer of war memorials in Canada; among his best-known sculptures is the Westmount War Memorial, Quebec, 1922, which features a winged figure pointing out the path of victory to a marching soldier. Hill’s other notable works include the Charlottetown War Memorial, Prince Edward Island, 1923–25, consisting of three charging soldiers with rifles on a granite pedestal, and the Sherbrooke War Memorial, Quebec, 1926, where the motif of three soldiers is repeated, but in this case at the base of the pedestal, from where they look upward to a winged figure representing victory. Although war memorials were numerous across the country, Allward’s work as a designer is unique in Canada, rejecting the conventional practice of representing soldiers in favour of a more provocative exploration of redemption and a future without war.

Monuments to Peace

Allward was deeply affected by the First World War, and his beliefs guided his approach to designing memorials. As he noted when reflecting on the Vimy Memorial, 1921–36, he created “a sermon against the futility of war….Vindictiveness and Hate have been excluded from my design. In my original drawings, I had a foot trampling on a German steel helmet. Even that symbol I removed.”

Like many of his generation, Allward accepted as an act of faith that the First World War was, in the words of H.G. Wells, “the war to end war,” tragic but necessary to defeat German militarism. This view is reflected in the design of his early First World War monuments, beginning with his two models for the proposed Bank of Commerce war memorial on King Street West in Toronto, The Service of Our Women—Healing the Scars of War and The Service of Our Men–Crushing the Power of the Sword, both 1918. The themes in those works reappear in the Stratford War Memorial, 1919–22, and the Peterborough War Memorial, 1921–29, both of which convey the message that Canadians killed in Belgium and France died to protect the values of civilization over barbarism and to put an end to future wars.

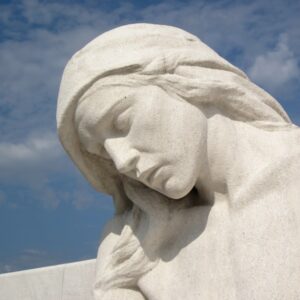

These ideas were more ambitiously expressed in the Vimy Memorial, which the historian Tim Cook describes as “a monument to peace, not victory, an homage to loss and death, and a call to remembrance.” Allward’s design for Vimy surpasses his earlier efforts by more explicitly envisioning the path to a more enlightened future, incorporating near the top of the twin pylons allegorical figures representing Peace, Truth, Knowledge, Justice, Faith, Charity, Hope, and Honour, values to which he hoped humankind would aspire.

When the memorial was completed in 1936, it was widely interpreted as a symbol of peace. A statement read on behalf of Prime Minister William Mackenzie King at the Vimy dedication service expressed this idea: “Canada asks that the nations of Europe strive to obliterate whatever makes for war and for death. She appeals to them to unite in an effort to bring into being a world of peace. This is the trust which we, the living, received from those who suffered and died. It is a trust we hold in common. A world at peace, Canada believes, is the only memorial worthy of the valour and the sacrifice of all who gave their lives in the Great War.” This view of the Vimy Memorial has remained constant for the more than eighty years since its unveiling.

Contribution to Canadian Sculpture

One of Allward’s most important milestones, marking his intellectual and artistic independence, was his eventual rejection of École des beaux-arts ideas of monument design, seen in works such as the John Graves Simcoe Monument, 1901–3, and the John Sandfield Macdonald Monument, 1907-9, including the pyramidal presentation of a static single figure on a pedestal. Instead, with works like the Bell Memorial, 1909–17, and the unfinished King Edward VII Memorial, begun 1912, he began to explore the dramatic possibilities of combining expressive classical figures, influenced by Michelangelo (1475–1564) and Auguste Rodin (1840–1917), with horizontal composition in a way that encourages viewers to move within the space of the monument. Allward continued to refine this approach with the Stratford War Memorial, 1919–22, and the Peterborough War Memorial, 1921–29, bringing it to perfection in the Vimy Memorial, 1921–36.

Allward had a profound impact on other sculptors in Canada. His high aesthetic and technical standards, and the positive reception of his work, significantly raised the profile of sculpture throughout the country, greatly benefiting other Canadian sculptors, including Emanuel Hahn (1881–1957), Frances Loring (1887–1968), Florence Wyle (1881–1968), and Elizabeth Wyn Wood (1903–1966). Hahn was especially close to Allward, having served as his assistant between 1908 and 1912, and the two remained friends until the latter’s death in 1955. As a token of their friendship, Allward bequeathed many of his personal sculpting tools to Hahn, with the request that they be passed from one generation of artists to the next. Allward’s willingness to expand the language of sculpture beyond the Beaux-Arts style and his commitment to various arts organizations were also important to these artists, all of whom would go on to become founding members of the Sculptors’ Society of Canada in 1928, a group that initiated many exhibition opportunities for Canadian sculptors while greatly expanding the language of sculpture in this country.

Among the sculptors Allward influenced, Loring was especially articulate about his impact and spoke often about the Vimy Memorial in the many illustrated lectures she presented. In an address to the Canadian Council of Women in Port Arthur, Ontario, in 1922, Loring described Allward’s masterpiece in detail: “There is no one doing as fine a type of monumental work as Mr. Allward. He had lived a lonely life, through lack of understanding by his fellow craftsmen, but his marvelous work in regard to the memorial has put him at the top of the ladder.” A few years later, she referred to Allward as “the greatest sculptor in Canada and for his monumental work, the best in the world. . . . Canada is only beginning to appreciate him now that Europe has been acclaiming his genius, but Canada doesn’t yet realize what he is. Now, for the Vimy Ridge memorial, he was given an absolutely free hand—and as a result you get a work of genius.” Loring expressed a view widely shared by Allward’s contemporaries.

Posthumous Recognition

A few months after Allward’s death in 1955, the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts included a selection of his drawings and plaster maquettes, along with photographs, in their 76th annual exhibition, held at the Art Gallery of Toronto (now the Art Gallery of Ontario). However, in the years that followed, Allward’s work received little critical attention until 1990, when Lane Borstad completed a catalogue of Allward’s drawings and sculpture as part of his Master’s degree.

The neglect of Allward’s works was related to a wider contemporary dismissal of sculpture’s contribution to the cultural life of Canada during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. One prominent study went so far as to suggest that before 1960 in Canada, there were “very few sculptors of substance. There was nothing that could really be considered to constitute a tradition, nothing either to follow or against which to react. Nor was there evidence indicating a real awareness of or interest in what had been occurring in European or American sculpture since the turn of the century.” Remarkably, this view not only overlooks Allward’s achievements but also those of numerous other early twentieth-century sculptors, Emanuel Hahn, Louis-Philippe Hébert (1850–1917), Frances Loring, and Elizabeth Wyn Wood among them.

Interest in Canadian sculpture was revived in the mid-1980s with the publication of Terry Guernsey’s Statues of Parliament Hill (1986) and the exhibition Loring and Wyle: Sculptors’ Legacy, shown at the Art Gallery of Ontario in 1987. A decade later, the National Gallery of Canada paid homage to two other prominent early twentieth-century sculptors in the travelling exhibition Emanuel Hahn and Elizabeth Wyn Wood: Tradition and Innovation in Canadian Sculpture.

Allward finally emerged from obscurity in 2001, with the publication of Jane Urquhart’s novel The Stone Carvers, a fictionalized account of Allward and the building of the Vimy Memorial, 1921–36, a work the author poignantly describes as “a huge urn…designed to hold grief.” Although his work then began to receive greater critical attention, most of the new scholarship focused on his crowning achievement, the Vimy Memorial. His career as a whole continues to be largely ignored.

Preserving Allward’s Legacy

Allward’s principal sculptures remain accessible to the public in their original settings. Many of them, including four of his works in Queen’s Park, the South African War Memorial, 1904–11, and the monuments in Stratford, 1919–22, in Peterborough, 1921–29, and at Vimy, 1921–36, have been restored in recent years, allowing the public to experience them in near pristine condition. The work carried out on the Vimy Memorial between 2005 and 2007, part of a larger Canadian government effort to repair First World War monuments in Europe, was the most ambitious art restoration project in Canadian history.

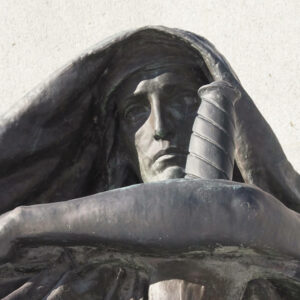

Allward’s legacy is also preserved in several smaller pieces, including sculptures and drawings, held by the National Gallery of Canada, the Art Gallery of Ontario, and Queen’s University Archives. In addition to these holdings, the collection of the Canadian War Museum includes seventeen of the twenty plaster figures that Allward created in London between 1925 and 1930 for the Vimy Memorial. The three other plaster figures, including Canada Bereft, are housed at the Military Communications and Electronics Museum in Kingston, Ontario.

Allward’s legacy is perhaps best enshrined at Vimy. In 1996 the Government of Canada officially designated the parcel of land (290 acres) on which the memorial stands a national historic site. Operated by Veterans Affairs Canada and officially known as the Canadian National Vimy Memorial, the site includes a visitor education centre that each year provides hundreds of thousands of visitors with information about Canada’s and Newfoundland’s role in the First World War. In 2002 Allward was named a National Historic Person on the recommendation of the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada. The plaque commemorating this honour, unveiled in July 2010 at the site of the Bell Memorial, 1909–17, in Brantford, Ontario, identifies Allward as “an outstanding sculptor of some of Canada’s finest public monuments,” who “emerged as a dominant figure in the transition from the sculptural conventions of the Victorian era to the more abstract forms of the 20th century.” Allward was also honoured with plaques by the Ontario Heritage Foundation in 2004, the Fort York branch of the Royal Canadian Legion in 2007, and the Friends of the Stratford War Memorial in 2018.

Reassessing Monuments Today

Recent events have intensified the debate over whether or not to remove from public spaces monuments commemorating controversial figures or events. In Canada the most famous figure to invite scrutiny is the country’s first prime minister, John A. Macdonald, who has been criticized for his role in setting up the country’s residential school system. The system forcibly separated Indigenous children from their families for extended periods and forbade them to acknowledge their heritage or to speak their own languages. In recognition of this injustice, a statue of Macdonald outside Victoria City Hall, British Columbia, was removed in 2018 as part of the city’s reconciliation program with local First Nations. Victoria’s city council reached this decision after discussions with Indigenous leaders and a public consultation process was subsequently initiated to determine the sculpture’s future home. As Canadians continue to scrutinize and challenge history, more critical dialogues about monuments are likely.

Allward’s sculptures have generally not attracted much in the way of negative attention. Two exceptions are the Northwest Rebellion Monument, 1894–96, a work erected following the suppression of an uprising lead by Métis leader Louis Riel in 1885, and the Nicholas Flood Davin Monument in Beechwood Cemetery, Ottawa, 1903, marking the burial place of Davin, a lawyer, journalist, and politician who wrote the report that led to the establishment of the residential school system in Canada.

For the Northwest Rebellion Monument, Allward sculpted a female figure of Peace. Canadians at the time largely viewed the government’s response to the uprising as necessary to maintain law and order in Western Canada. That perspective has since changed, and it is now widely acknowledged that the conflict denied Métis sovereignty; the events are now commonly referred to as the Northwest Resistance. In 2017, because of the monument’s ties to Canada’s colonial past and to the loss of Métis sovereignty, the Métis Nation of Ontario adopted a resolution at its annual general assembly to move the main part of their annual Louis Riel Day ceremonies, which had been held on November 16 at the Northwest Rebellion Monument since 2011, to a different site. To date no demands have been made to remove the work. Reconciliation efforts, however, might include adding a plaque to the pedestal, in recognition of the Métis and other Indigenous peoples who died in the conflict. Such a marker would be consistent with an intervention adopted at the Davin gravesite in Beechwood Cemetery, with its portrait bust by Allward from 1902, where a historical plaque was installed in front of the monument in 2017, noting Davin’s authorship of the report that served as the basis for Canada’s residential schools. This approach views public monuments as historical markers, points of entry to a better understanding of events in Canadian history.

Allward’s early work mainly depicts prominent Canadians—Sir Wilfrid Laurier, George William Ross, and Sir Oliver Mowat among them—who did not implement policies that are currently considered controversial. After completing the Bell Memorial in Brantford in 1917 his efforts were focused on memorializing Canadians killed in the First World War. In these works, culminating in the Vimy Memorial, 1921–36, Allward rejected typical depictions of military subjects, choosing instead to design monuments that expressed redemptive themes. His final sculpture marks the role of William Lyon Mackenzie in establishing responsible government, a forerunner of Canada’s parliamentary democracy. Viewed as a whole, Allward’s body of work continues to present Canadians with essential lessons in history.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements