Walter S. Allward (1874–1955) began life modestly in Toronto and against all odds became the foremost sculptor of his generation. He left school at fourteen and learned about sculpture by looking through books and magazines at the local library and by studying replicas at a nearby museum. By twenty, he had won his first commission and never looked back. His landmark works—the Bell Memorial; the Brantford, the Stratford, and the Peterborough war memorials; and especially his masterpiece, the Vimy Memorial in France—transformed sculpture. Despite his enormous success, Allward was largely ignored in the years after his death until 2001, when he appeared as a fictional character in Jane Urquhart’s novel The Stone Carvers.

Early Life

Walter Seymour Allward experienced adversity at an early age. He was born on November 18, 1874, to John A. Allward (1833–1903) and Emma Pittman (1839–1905). His father was raised in St. John’s, Newfoundland, where he apprenticed as a carpenter. His mother, the eldest daughter of James Pittman, a master shipbuilder, came from the coastal town of New Perlican. In 1869, as a consequence of the decade-long economic depression, John, Emma, and their children (Charles, Elizabeth, Mary, and James) moved to Toronto, where Walter and two of his siblings were born. The city offered John more opportunities but supporting his growing family continued to be difficult. During Walter’s early years, the family moved several times, mostly remaining in east Toronto.

As a child, in addition to experiencing economic hardship, Walter was affected by the loss of four siblings, all of whom died in childhood before he reached the age of ten. Despite these troubles, he grew up in a protective environment insulated by his parents, his two older siblings, and an extended family that included two of his mother’s sisters, Sarah and Mary. The youngest of John and Emma’s surviving children, he found refuge in art as a way to express his emotions and to give free rein to his imagination. His sister Elizabeth later noted, “Walter was always artistic. As a child he was always drawing and modelling and dreaming, dreaming of the great things he would someday do in art.” He was already fascinated by sculpture; one of his earliest creative pastimes was making figures from clay that he found in abundance along the banks of the nearby Don River. In later years, he attributed his artistic success to the values instilled by his parents, praising his father for “his refusal to be satisfied with anything but good work,” and his mother, “a woman of unusual strength of character and fine spiritual quality,” for encouraging the development of his imagination.

Becoming an Artist

For Allward, the path to becoming a sculptor was unconventional. He attended Dufferin School on Berkeley Street in the mainly working-class district of St. David’s Ward until he was fourteen, when he began helping his father with carpentry work. Although economic considerations were likely a factor, Allward later stated, “I was never a scholar. I always liked better to do things with my hands than to study.”

Despite a keen interest in sculpture, Allward chose a more financially prudent path in 1890, beginning an apprenticeship as a draughtsman with an architectural firm headed by Charles Gibson (1862–1935) and Henry Simpson (1865–1926). When the company was dissolved the following year, he continued to work under Simpson, who had set up his own practice. Simpson’s principal commissions at that time included Cooke’s Presbyterian Church on Queen Street East (1891) and Bethany Chapel on University Avenue (1892). Allward remained in his employ until 1894, producing blueprints and presentation drawings and gaining a deep understanding of architecture that would serve him well.

During this period, still intent on pursuing a career in art, Allward studied painting under William Cruikshank (1848–1922). Although this interest was short-lived, he maintained a close friendship with Cruikshank over the next two decades. As a member of numerous art societies, including the Ontario Society of Artists and the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts, Cruikshank provided Allward with his first glimpse of Toronto’s art world. He may also have steered Allward toward the Toronto Art Students’ League (TASL), which had originated as a sketch club in 1886. Allward became a member of the TASL in the early 1890s, which provided him with opportunities to refine his drawing skills and to interact with other artists.

Compared with other late nineteenth-century Canadian sculptors, including Louis-Philippe Hébert (1850–1917) and George W. Hill (1862–1934), Allward had hardly any formal training in art. Hébert spent eight years as an apprentice to the architect and painter Napoléon Bourassa (1827–1916) in Montreal, followed by three years in Paris, where he learned the complex techniques involved in bronze casting. Hill also developed his skills in Paris, attending the Académie Julian and the École des beaux-arts. For both artists, studying European sculpture was critical to their future work. Unable to afford studies in Europe, Allward embarked upon a different path.

Allward later recounted that his interest in sculpture emerged in his late teens through exposure to ancient Greek sculpture and the art of Michelangelo (1475–1564) in books and magazines at the Toronto Public Library and by studying sculpture replicas at the city’s Educational Museum. He also became captivated by the French sculptor Auguste Rodin (1840–1917), whom he especially wished to emulate. Allward later remarked, “Rodin’s work, among the moderns, made a very strong appeal to me then, and still, does. It lives. I felt I wanted to do work like it.”

At the outset, Allward pursued his interest in sculpture with little encouragement from family or friends and under unrelenting pressure to earn a living. His only direct training was from evening modelling classes in the early 1890s at the new Technical School in Wycliffe Hall on College Street and, beginning in 1894, through employment at the recently opened Don Valley Pressed Brick Works, where he created bas-relief and three-dimensional sculptures in terracotta for architectural decoration. Allward was gradually developing skills that would allow him to devote his life to sculpture.

Early Monuments and Private Commissions

In 1894, at age nineteen and having only minimal training as a sculptor, Allward entered and won a competition to design a bronze statue of Peace for the Northwest Rebellion Monument in Queen’s Park, near the recently opened Ontario Legislative Building. Erected to commemorate the end of the Northwest Rebellion (now known as the Northwest Resistance) led by Louis Riel in what is now the province of Saskatchewan, the monument marked a turning point in Allward’s life and the beginning of his career as a sculptor.

The project was directed by D. McIntosh & Sons, a prominent manufacturer of public and funeral monuments based in Toronto. Allward’s lack of experience meant that he worked slowly, which resulted in complaints from his employer, who had provided money in advance for his studio and tools. Confident in his artistic abilities, Allward threatened to destroy the sculpture if the company continued to exert pressure. The McIntosh representative relented, but when Allward arrived at the site the next morning a guard was stationed beside the figure, an arrangement that continued until he completed the sculpture.

Designed according to the then popular Beaux-Arts style, the monument has a single figure on a pedestal within a pyramidal composition. It was a critical success, with one reporter noting, “Mr. Allward has succeeded in producing a work of true artistic feeling, one that will be a credit to the city as well as to the artist.” Allward attended the unveiling on June 27, 1896, and when the crowd called out for him to speak, he responded with a modesty that became one of his hallmarks: “I thank you for your appreciation of my work. It is not what it might have been, but it was the best I could do. Probably I will do better next time.”

In his early years, Allward struggled to support himself as a sculptor. He shared living quarters for a time with the artist Frederick Challener (1869–1959), in a large room on the top floor of an office building in downtown Toronto. As he later recounted, both were so short of money that they would often subsist for days on little but oatmeal porridge. The two would remain lifelong friends. In 1902 Allward was a model for Challener’s painting A Singing Lesson, and in 1906 Allward’s son Hugh posed for the figure of Cupid in Challener’s mural Venus and Attendants Discover the Sleeping Adonis, situated above the proscenium arch of Toronto’s Royal Alexandra Theatre.

Although he aspired to work on large sculptures and later became known primarily for his public monuments, Allward occasionally accepted private commissions. In 1896 he was awarded a contract to produce granite sculptures of Drama, Victory, and Music for a mausoleum erected by Robert Fulford in memory of his wife, the celebrated actress Annie Pixley. Located in Woodland Cemetery in London, Ontario, the Pixley Mausoleum was designed by the London-based architectural firm Moore and Henry and constructed under the supervision of D. McIntosh & Sons, who had hired Allward on the strength of his work on the Northwest Rebellion Monument.

Subsequently, in 1897, Allward submitted a bid to design a bronze sculpture honouring Dr. Oronhyatekha, a Kanien’keha:ka physician and one of the first accredited Indigenous medical doctors in Canada, who became the chief executive of the Independent Order of Foresters (IOF), one of the largest insurance companies in Canada. Oronhyatekha embarked upon an ambitious plan to construct a new headquarters, the Temple Building, at the corner of Bay and Richmond streets in Toronto. Once it was underway, the company announced a competition for a sculpture of Oronhyatekha for the main lobby. Allward’s bid was chosen ahead of entries from Europe, the United States, and Canada. When the work was unveiled in June 1899, he was lauded for his realistic portrayal, confirming his rising reputation as an artist.

Allward’s financial situation began to improve in the late 1890s, when he was commissioned by the Educational Museum at the Toronto Normal School (a teacher’s college) to produce plaster portrait busts. The program had been initiated in 1887 with the goal of assembling a collection of “famous men of all ages.” Intended for educational purposes, seventy-eight busts were eventually made, most by Allward and two older and more experienced sculptors, Hamilton MacCarthy (1846–1939) and Mildred Peel (1856–1920). Allward’s early contributions included busts of the British poet Alfred Tennyson, in 1897, and Canada’s sixth prime minister, Sir Charles Tupper, in 1898.

It was through that project that Allward met his future wife, Margaret Kennedy. The youngest child of Angus Kennedy and Margaret McGillivray from Galt, Ontario, Margaret was studying at the Toronto Normal School when she met Allward. The couple married on September 14, 1898, and on Christmas Day of the following year they celebrated the birth of their first child, Hugh Lachlan Cruikshank Allward.

Over the next few years Allward accepted additional commissions from the Educational Museum, sculpting portrait busts of Sir George Burton, Chief Justice of Ontario; Sir Wilfrid Laurier, Prime Minister of Canada; and Sir George William Ross, Premier of Ontario, among others. Each reflects Allward’s acute powers of observation and exacting use of detail. The busts of Burton and Laurier were shown at the twenty-second annual exhibition of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts in Toronto in April 1901 (the first time Allward’s work was presented in an official art exhibition) and, later that year, at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York, where he was awarded a silver medal.

Although there is no conclusive evidence that Allward travelled the short distance from Toronto to Buffalo for the exhibition, he likely did. There, he would have had his first opportunity to view outstanding examples of recent American sculpture, including several works by the highly acclaimed George Grey Barnard (1863–1938), Daniel Chester French (1850–1931), and Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1848–1907). Allward was especially drawn to the work of Saint-Gaudens, describing him in 1911 as “perhaps the greatest American sculptor of modern times.”

Toronto’s Most Promising Sculptor

The first decade of the new century was eventful for Allward, both personally and professionally. His father and mother died two years apart, in 1903 and 1905, respectively, and on June 6, 1906, he and Margaret celebrated the birth of their second son, Donald John Pittman Allward. In his professional life, Allward emerged as Toronto’s most promising sculptor.

Allward’s early career coincided with a new stage of growth and prosperity in Toronto. Particularly important was the development of Queen’s Park and the construction of the new Ontario Legislative Building (1883–96), which would serve as an ideal location for monuments honouring prominent figures. After the positive response to the Northwest Rebellion Monument, 1894–96, from the public and critics alike, Allward was in a favourable position to compete for the many sculptures commissioned for Queen’s Park.

In May 1901 Allward was chosen to design a monument honouring John Graves Simcoe, who was the first Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada. Organized and managed by the Toronto Guild of Civic Art, the competition included entries from American and European sculptors. Byron Edmund Walker (1848–1924) (later Sir Edmund Walker), the first president of the guild, supported Allward’s proposal and would play a major role in his evolution as a sculptor in the years that followed.

The success of the Simcoe Monument led to further commissions. In 1903 Allward was chosen by Ontario Premier George William Ross to produce a sculpture for Queen’s Park commemorating Sir Oliver Mowat, a former premier of the province. For this work, Allward combined a traditional full-length statue of Mowat with bas-relief allegorical figures representing Jurisprudence and Justice. In 1906 the plaster models for the panels were included in the winter exhibition of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia.

Allward’s years of financial insecurity were now behind him. In 1902 he purchased a property on Walker Avenue west of Yonge Street in what was then north Toronto. Over the next two years, he designed and built an Arts and Crafts–style house and studio, which one visitor later described as “a profoundly quiet place.” It was here that he would spend time with his family, entertain friends, and work on various commissions.

Allward’s reputation was further enhanced by his sculpture of an old soldier for the War of 1812 Memorial in Toronto’s Portland Square. Although it was delayed because of a lack of funds, the monument was enthusiastically received when it was finally unveiled in early 1907. A reporter for the Globe newspaper noted that “of the artistic qualities of this distinguished piece of work one can only speak in terms of the highest praise. The indomitable courage… is depicted by Mr. Allward with a reverent hand, and the horror of war is made to reach the consciousness through the poignant pathos of the aged and broken veteran.”

More than in any previous work, Allward presented his subject symbolically rather than realistically, accentuating the old soldier’s inner anguish. In so doing, he paid homage to Auguste Rodin, whose work he had long admired, and which he was finally able to see first-hand during a summer trip to London and Paris with Margaret in 1903.

An Artist in Demand

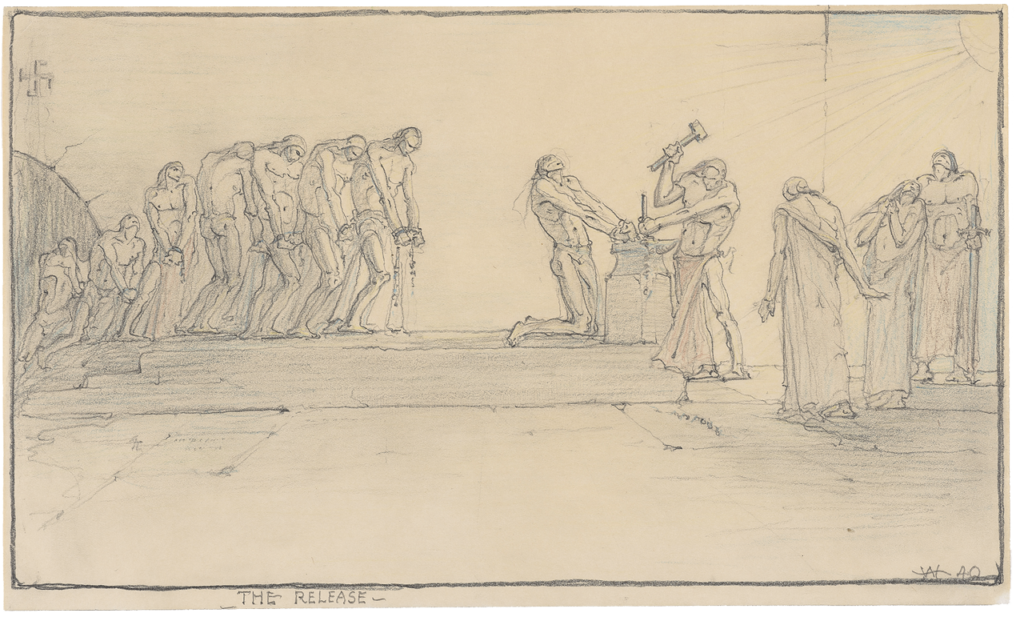

Most early twentieth-century sculpture competitions set specific parameters for submissions; for artists like Allward, those that allowed for greater creative freedom were invariably more rewarding personally, as he could move beyond traditions. The call to create Toronto’s South African War Memorial, 1904–11, was such a commission—and it was one of Allward’s most important works. As the art enthusiast James Mavor wrote about him in 1913, “the works which are most indicative of his genius are those in which there is some opportunity for the exercise of the imagination…Where Allward shines is in those compositions where he is free to select or to design his figures, and to dispose them in such a way as to suggest some symbolism and at the same time to offer fine lines.”

The South African War Memorial commemorates the 267 Canadian volunteers who died in the Boer War between 1899 and 1902. The conflict marked Canada’s first official dispatch of troops to an overseas battle, one between Britain and two independent Boer states, the South African Republic (Republic of Transvaal) and the Orange Free State, and it had widespread public support. The monument features a granite base with a group of three sculptures in bronze. The central figure represents Canada, pointing out the path of duty to two Canadian soldiers, and was inspired by and modelled after Allward’s mother, who had seen four of her children die before adulthood. Rising from the base and behind the three figures is a seventy-foot column capped by a bronze allegorical depiction of Victory.

With its multiple figures and soaring column, the South African War Memorial was Allward’s most ambitious work to date. Despite the demands of the project, he continued to take on additional work, including a monument honouring Ontario Premier John Sandfield Macdonald for Queen’s Park in 1907. The following year he submitted a sketch model to the newly formed Advisory Arts Council (AAC) for a monument on Parliament Hill commemorating the Honourable Robert Baldwin and the Honourable Louis-Hippolyte Lafontaine, whose collaboration led to the establishment of responsible government in 1848, a forerunner of Canada’s parliamentary democracy. The AAC determined that Allward’s proposal was superior to others, including entries from Louis-Philippe Hébert, George W. Hill, Alfred Laliberté (1878–1953), Coeur-de-Lion MacCarthy (1881–1979), and Hamilton MacCarthy, all of whom were well-established sculptors in Canada. The committee was so impressed by Allward’s design that they arranged for the sketch model to be displayed for several weeks in the main entrance hall of the Centre Block of the Parliament Buildings.

In 1908, as demand for his work increased, Allward hired the sculptor Emanuel Hahn (1881–1957) to be his studio assistant. Hahn had earlier been employed at D. McIntosh & Sons, producing mainly bronze reliefs for monuments. His first task in his new job involved enlarging the model figures for the South African War Memorial using a mechanical measuring device that Allward had designed. He continued to work with Allward until 1912, contributing to the Baldwin–Lafontaine Monument and to the Bell Memorial, 1909–17.

Although Allward was, by all accounts, introspective and solitary, he valued the company of other artists, including Frederick Challener and William Cruikshank, with whom he became close friends during his formative years. By 1908 he was busy with three major projects—the Baldwin–Lafontaine Monument, the John Sandfield Macdonald Monument, and the South African War Memorial—but he was also active in the leading artists’ groups in Toronto. He joined the art critic Augustus Bridle and the artists E. Wyly Grier (1862–1957), George Agnew Reid (1860–1947), and Hahn in founding the Arts and Letters Club in Toronto, whose goal was to allow members “to seek among themselves a genial companionship, and to increase the sympathy between the various branches of the arts.” Allward served on the executive from 1908 to 1911.

In 1909 Allward became a member of the newly established Canadian Art Club (CAC), which had been formed in 1907; founders included artists Franklin Brownell (1857–1946), Edmund Morris (1871–1913), and Homer Watson (1855–1936). One of the group’s main activities was an annual exhibition held both in Toronto and Montreal. Allward participated in two, presenting a sketch model of the Bell Memorial in the fifth annual exhibition (1912) and another of the King Edward VII Memorial, Ottawa, in the sixth annual exhibition (1913).

Allward was also a long-time member of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts (RCA). He was elected an associate member in April 1903, two years after contributing portrait busts of Sir George Burton and Sir Wilfrid Laurier to the RCA’s annual exhibition. However, he resigned in November 1910 in protest against the rule that required members to regularly contribute to the group’s exhibitions, a stipulation that was especially burdensome for sculptors, given the time and costs expended in producing a work. He rejoined two years later after the organization allowed sculptors to submit a photograph of an important work in lieu of a statue or model. In 1914 Allward was voted an Academician of the RCA, one of the highest professional honours for Canadian artists.

Pushing the Boundaries of Canadian Sculpture

The South African War Memorial in Toronto was formally dedicated in May 1910 but without the statue of Victory, whose completion had been postponed because of insufficient funding and shipping delays. Despite its unfinished state, the monument was widely praised as Allward’s boldest and most successful work, an assessment confirmed when the final bronze sculpture was installed in August 1911.

In 1909 Allward had begun work on the Bell Memorial in Brantford, Ontario. With its horizontal design, the work is widely acknowledged as his first sculpture to break fully with the Beaux-Arts style, which had informed his earlier monuments. The project was initiated to commemorate the invention of the telephone by Alexander Graham Bell. Allward’s description, which he submitted to the organizing committee with a sketch model, noted that the female figures in bronze mounted on granite pedestals at each end of the horizontal monument symbolized the telephone’s ability to span vast distances.

As with many of Allward’s projects, the Bell Memorial was beset by delays, partly because of other commitments. For instance, in early 1912 he submitted to the Arts Advisory Council a sketch model for a monument on Parliament Hill commemorating King Edward VII, who was widely hailed as “Peacemaker,” owing to his fostering of good relations between Britain and other European countries, particularly France. Allward’s design, a continuation of his exploration of horizontal composition, was ultimately chosen from proposals submitted by more than forty sculptors. The work featured Edward VII standing in front of a wall, on top of which Allward added a reclining figure symbolizing Peace. An inscription below this figure and behind the King reads: “Through Truth and Justice he strove that War might cease and Peace descend o’er the earth.” Allward would never finish the monument, owing to the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914.

The First World War and New Memorials

Like most Canadians, Allward was preoccupied with events in Europe throughout the First World War (1914–1918). By the end of hostilities, some 619,000 men and women had enlisted in the Canadian Expeditionary Force for service overseas, while hundreds of thousands of others worked on the home front. Allward’s unease with the violence is reflected in several pen-and-ink drawings, including The Battlefield, 1916, in which Christ stands before a mass of corpses. The impact on him and his desire to help are evident in an evocative letter he wrote to the Canadian government in early 1917, offering to delay his professional work in order to create prostheses for facially disfigured soldiers: “I am a sculptor and would be able to model the missing parts…If I can be of any service to my country in this direction, I will gladly do what I can.” Unlike their counterparts in Britain and the United States, the Canadian government had not yet implemented a program to create prosthetic parts for wounded soldiers.

More than 61,000 Canadians and Newfoundlanders perished during the conflict and, after the war’s end, towns and cities throughout the country sought ways to honour them. Canadians had no previous experience of such a large-scale sacrifice, and the sense of loss was heightened by the government’s decision, based on practical considerations, not to repatriate the bodies of the men and women who had died overseas. In the immediate post-war period, hundreds of memorials were erected in communities across the country, with most initiated by local citizens and largely funded through public donations.

One of Allward’s first memorial projects developed through his friendship with Sir Edmund Walker. In 1918, in his capacity as President of the Bank of Commerce, Walker asked Allward to develop ideas for a memorial honouring bank employees who had served. The following year, Allward submitted wax models for two monumental sculptures. The first, The Service of Our Women—Healing the Scars of War, depicts a woman sowing seeds on rocky incline strewn with war debris, including a broken canon. The second, The Service of Our Men–Crushing the Power of the Sword, portrays a man standing over a recumbent figure with his sword cast aside, symbolizing the “brute beast of willful war waged by a misguided nation.” Although the sculptures were never realized, Allward’s proposals explored ideas that would be expressed in his future war memorials (Stratford, 1919–22, Peterborough, 1921–29, and Brantford, 1921–33), emphasizing that “the power of benevolent ideas in evolution will tend to make the savagery of war impossible.”

True to his own values and consistent with views that had taken hold throughout the country, Allward emphasized the sacrifice of lives rather than glorifying war. Of the three commissions, he chose to proceed first with the Stratford project, whose theme was “the supremacy of right over brute force.” He worked on the monument’s two figures throughout the early months of 1921, completing the clay models by July. Reporting on a visit to Allward’s studio, George Kay, a member of the committee overseeing the project, captured Allward’s deep attachment to his work and the degree to which he had been affected by the war, noting,

Mr. McPherson and I were invited to inspect the completed model of one of the two figures to be erected…The figure which he has completed is that of “Defeat,” which he said he had tackled first as being much more the difficult of the two, owing to the dejected posture and aspect of the brute. It is about 8½ feet high and Mr. McPherson and I thought it a very satisfactory representation of a most unlovely character, and we quite believed Allward when he said that during the latter stages of its creation he suffered severely from “the blues” due solely to enforced association with it.

The monument in Stratford would be completed in 1922, but Allward was unable to attend its unveiling nor was he making substantial progress on the Brantford and Peterborough projects. Instead, he focused on the design and construction of what would be his most ambitious and demanding work, the Vimy Memorial, 1921–36.

“This Glorious Monument”

While Allward was occupied with local monuments, plans for Canadian national memorials in Europe were also taking shape. In May 1920 a House of Commons special committee recommended that permanent memorials be erected in France and Belgium to pay tribute to the sacrifice of Canadians during the First World War. That September the government formed the Canadian Battlefields Memorials Commission (CBMC), a seven-member body that subsequently proceeded with plans to erect monuments on eight battle sites that Belgium and France had granted to Canada.

Initially planning to replicate a single monument on each of the eight sites, the CBMC launched a national competition open to all Canadian architects and sculptors in December 1920. In response, 160 entries, presented in the form of drawings, were submitted. Seventeen finalists, including Allward, were given a stipend to provide a model and a description based on their original drawing. On October 4, 1921, the jury unanimously chose Allward as the winner and Frederick Clemesha (1876–1958), a Regina-based architect and former lieutenant in the 46th Battalion (South Saskatchewan), Canadian Expeditionary Force, as the runner-up.

The jury was impressed by the “individuality and complexity” of Allward’s design, which included twin pylons and twenty allegorical figures, and decided that the memorial should be developed as a single monument in one location. The site originally chosen was Hill 62 near Ypres, Belgium, but this location was changed to Vimy Ridge in France, first through the efforts of Peter Larkin, High Commissioner in London, and Colonel A.F. Duguid, director of the historical section at the Department of National Defence, and finally through the intervention of Prime Minister Mackenzie King, who viewed the site as “hallowed ground”. Vimy Ridge was the scene of one of the First World War’s most decisive battles, marking the first time that all four divisions of the Canadian Corps fought under a single command, but at a cost of 3,598 Canadian lives.

Allward left Toronto for France in June 1922 with his wife and two sons with the expectation that the Vimy Memorial would be completed within five years. In Paris, his first objective was to find an appropriate studio. After extending the search to rural France and Belgium without success, the Canadian government intervened and purchased for Allward the former house and studio of the English sculptor Sir Alfred Gilbert (1854–1934), at 16 Maida Vale in London. Despite its location, a full day’s journey to the Vimy site, Allward was relieved to be in his new home, which he described to Sir Edmund Walker as “a rather beautiful place, lots of studio rooms, and a place in which you can forget the outside world.”

There, Allward set to work on the most formidable project of his career. He spent nearly two years preparing architectural plans and travelling throughout Britain and Europe in search of a stone that possessed a colour, texture, and luminosity suitable for the north of France. He eventually found his ideal material in an ancient Roman quarry at Split, in Croatia. Once it reopened in 1925, the quarry provided more than 6,000 tons of Seget limestone for the memorial. The stone was shipped via Italy, and then transported to France by truck and by rail. The first delivery arrived at the site in 1926.

-

Men working blocks of stone in Pietrasanta, Italy, for the Vimy Memorial, n.d.

Photographer unknown

-

Dressed stone blocks in work yard, n.d.

Photographer unknown

-

Two men walking in front of the Vimy Memorial pylons covered in scaffolding, September 10, 1932

Photographer unknown

-

Unidentified person stands next to the blocks for the Female Mourner, n.d.

Photographer unknown

In the meantime, workers at Vimy were busy excavating war debris, such as explosives and wire, as well as human remains. When the ground was finally cleared, the British structural engineer Dr. Oscar Faber supervised the construction of the memorial’s massive concrete substructure. The cornerstone was laid in September 1927.

Allward had begun working on the sculptures in his London studio in the mid-1920s, starting with the figure Canada Bereft. Yet, even as the Vimy project progressed, he did his best to honour his commitments in Canada. His proposal for the Peterborough War Memorial had been accepted in 1921, but work on that project was set aside as he focused on completing the Stratford War Memorial, 1919–22, before leaving for France. The fate of the Brantford memorial was beyond Allward’s control. He had submitted three different sketch models, but the Brant War Memorial Association, organized to oversee construction of the monument, was unable to raise the money needed. Failing for a second time to obtain the funds for Allward’s design, whose main features included two granite pylons rising above a stone of remembrance, three bronze figures, and a piece of damaged field artillery, the committee decided in the early 1930s to erect the memorial without the bronze figures.

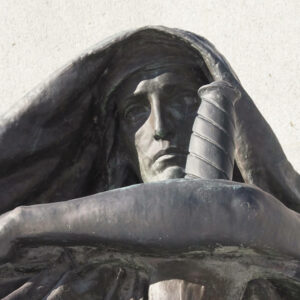

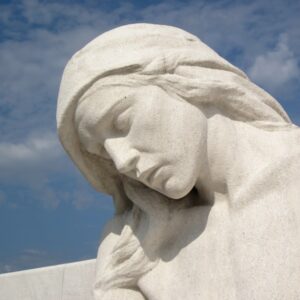

In London, Allward completed Canada Bereft and the other sculptures for the Vimy Memorial, first in clay and then in plaster, before sending them to the site, where, beginning in 1930, stone carvers supervised by Luigi Rigamonti (1872–1953) used an enlarging device called a pantograph to create double-size versions, which were carved from large single blocks of stone. Far behind schedule, Allward had temporary studios built around the figures so that work could continue in all weather conditions.

In May 1934 Allward received news that his son Donald, an aspiring sculptor who was helping him with the Vimy Memorial, had died after falling from a third-storey window while on holidays in Dinard, France. Despite the sudden loss, and the extra responsibility of caring for Donald’s five-year-old son, Peter, Allward remained focused on the last stages of the project, overseeing the carving of the figures and the engraving of the 11,285 names of Canadian soldiers who died in France and whose bodies were never recovered. The final details, which included removing the makeshift studios and thoroughly cleaning the monument, were completed by the end of May 1936. In June, Allward emptied his London home and studio and moved with his family to the market town of Hythe on the English coast, making it easier for him to travel to the Vimy site.

The unveiling ceremony of the Vimy Memorial took place on July 26, 1936, officiated by King Edward VIII in the presence of President Albert Lebrun of France and an estimated 100,000 spectators, including more than 6,000 Canadian veterans and their families. Allward was ambivalent about going, stating to his friend Emanuel Hahn, “my only desire is to leave everything right and forget it,” but he relented, witnessing the proceedings from an area at the base of the pylons that had been reserved for government officials and special guests.

-

Vimy Memorial with view of bombed battlefield and trenches in front

-

Walter S. Allward, Vimy Memorial, 1921–36

Seget limestone and concrete

Parc Mémorial Canadien, Chemin des Canadiens, Vimy, France

-

Aerial view of the Vimy Memorial dedication ceremony, 1936

Photographer unknown

Among those to address the large crowd was Ernest Lapointe, Canadian Minister of Justice, who, speaking on behalf of Prime Minister Mackenzie King, who was unable to attend, stated, “The grandest tribute we could offer to Canadian soldiers is to affirm that their sacrifices have contributed to the introduction into our civilization of its highest modern conception—that of universal Peace founded on recognition of the basic right of people to life and justice.” Following Lapointe, the King, standing on a raised platform next to Canada Bereft, said: “For this glorious monument crowning the hill of Vimy is now and for all time part of Canada….We raise this memorial to Canadian warriors. It is the inspired expression in stone chiseled by a skillful Canadian hand of Canada’s salute to her fallen sons.”

Return to Canada

After fourteen years abroad, Allward returned to Canada with his wife, Margaret, and his grandson Peter, satisfied that he had created a memorial that was both “worthy of the men who gave their lives” and “a protest in a quiet way against the futility of war.” He was also happy to be home, noting in a letter to Emanuel Hahn: “We will leave good friends here…but one’s heart is what one should follow and ours are very much in Toronto.”

In Canada, Allward’s accomplishment was widely celebrated. In 1937 he was awarded an honourary Doctor of Laws degree from Queen’s University, Kingston, and was named a Fellow of the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada, “in recognition of his outstanding achievement in the design and execution of the Vimy Memorial.” He was the guest of honour at the institute’s annual dinner, which included the reading of letters from such dignitaries as Colonel H.C. Osborne, secretary of the Canadian Battlefields Memorial Commission; Prime Minister Mackenzie King; Eugène Beaudoin, chief architect for the French government; and Sir Edwin Lutyens, the distinguished British architect who in 1933 had described the Vimy Memorial as “a great masterpiece.”

In June of the following year, Mackenzie King again acknowledged Allward’s triumph when he put forward a motion in the House of Commons stating, “this House desires particularly to express its appreciation to the services of Mr. Walter Allward, who, as the designer and architect of the memorial at Vimy, has given to the world a work of art of outstanding beauty and character.” In 1939 Allward received an honourary Doctor of Laws degree from the University of Toronto and in 1944 he was appointed a Companion of the Order of St. Michael and St. George.

Even as he was being celebrated, however, Allward discovered that during his time in Europe interest in public sculpture had diminished significantly and that sculptors were mostly producing smaller works for exhibition. Sculptors were also beginning to explore different modes of aesthetic and personal expression, rejecting the patriotic tendencies of Allward’s work. The shift was evident at the first exhibition of the newly formed Sculptors’ Society of Canada at the Art Gallery of Toronto (now the Art Gallery of Ontario) in October 1928, which featured work by artists moving in a modernist direction, including Emanuel Hahn, Elizabeth Wyn Wood (1903–1966), Frances Loring (1887–1968), and Florence Wyle (1881–1968). Bertram Brooker (1888–1955), a leading advocate of modernism in Canada, captured this sensibility is his description of Hahn’s work as “a free and imaginative approach to the arts . . . encouraging a new and untrammeled expression, characteristic of our environment here and growing out of it, without servile submission to the academic aims of older countries.” After his return, Allward received only one major commission, the William Lyon Mackenzie Memorial in Queen’s Park. The project was spearheaded in late 1936 by Mackenzie King to commemorate the role of his grandfather, William Lyon Mackenzie, in the struggle to establish democratic government in Upper Canada, and it was finished four years later.

Final Years

After completing the Mackenzie monument in May 1940, Allward’s creative output consisted mainly of drawings, among them designs for future monuments, including a grand memorial commemorating the British evacuation of Dunkirk, and a series of more than one hundred war cartoons in graphite and crayon that expressed his despair and disillusionment with the onset of the Second World War in Europe. The war cartoons were highly personal works, never shown in public during his lifetime.

During the war years of the Second World War, and especially during the Nazi invasion and occupation of France, Allward was anxious over the possibility of damage to the Vimy Memorial, 1921–36. His concern was heightened in late May 1940, when Canadian newspapers reported that German bombers had deliberately destroyed the monument. On June 2, in an effort to disprove Canadian charges, Adolf Hitler visited the site, where he had pictures taken before assigning special troops from the Waffen-SS to guard the memorial. These images were suppressed by the Canadian press, but when reports began to leak out that the monument in fact had not been destroyed, Prime Minister Mackenzie King felt it necessary to make a statement in Parliament in early August correcting earlier claims. Despite official reassurances, Allward remained uneasy until the British regained control of northern France in September 1944 and were able to state with absolute certainty that the Vimy Memorial had survived intact. Upon hearing the news, Allward told a reporter, “You have relieved my mind a lot. I’ve been worrying about it for a long time ever since that report away back in 1940 that it had been damaged.”

At the height of the Second World War, the University of Toronto asked Allward to submit a proposal for a memorial to Sir Frederick Banting, who in 1921 had discovered insulin at the university with the help of Charles Best. Banting had died in a plane crash in 1941, and the university formed the Banting Memorial Committee to explore a way of honouring him. In late 1943 the committee asked Allward to prepare designs and to help select an appropriate site. He presented his first sketches months later, stating that he strongly favoured a design that would convey “the gratitude of the people for the relief provided by the discovery of insulin.” Allward produced numerous drawings and eight sketch models over the next year, but the project was ultimately cancelled because of costs.

After the death of Margaret, his wife of more than fifty years, in Toronto in 1950, Allward spent most of his time at the house and studio he had designed and built in a secluded area in York Mills. Although he continued to sketch, he produced no further public sculptures, leaving him time to spend with friends and family, including his son Hugh, who had built a house nearby, and his grandson Peter, who was establishing a career in architecture. He died at home on April 24, 1955, at the age of eighty, and was buried beside Margaret in St. John’s Anglican Church cemetery. Obituaries were published in newspapers across the country, with one account noting that Allward’s legacy as one of Canada’s most important sculptors was secure “by the common consent of fellow artists and the public alike.” No one could have foreseen that the artist who had brought the Vimy Memorial to life would be almost completely forgotten for the next several decades.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements