Since his death, Tom Thomson has been Canada’s best-known and most-loved artist. For successive generations of artists right up to the present, he has set the baseline for Canadian art. His reputation has never wavered—curators, critics, and art historians have all acknowledged his supremacy, whether alone or as an unofficial member of the Group of Seven.

The Group of Seven

Thomson died before the Group of Seven was formed, but his friends and colleagues never doubted that, had he lived, he would have joined them. Lawren Harris (1885–1970) wrote in The Story of the Group of Seven:

I have included Tom Thomson as a working member, although the name of the Group did not originate until after his death. Tom Thomson was, nevertheless, as vital to the movement, as much a part of its formation and development, as any other member.

The Group of Seven formally came together in March 1920 when Harris invited five artists to his home at 63 Queen’s Park (now the site of the Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies at St. Michael’s College, University of Toronto): Franklin Carmichael (1890–1945), and Frank Johnston (1888–1949), Arthur Lismer (1885–1969), J.E.H. MacDonald (1873–1932), and Fred Varley (1881–1969). A.Y. Jackson (1882–1974) would have been present but was on a painting trip in Georgian Bay.

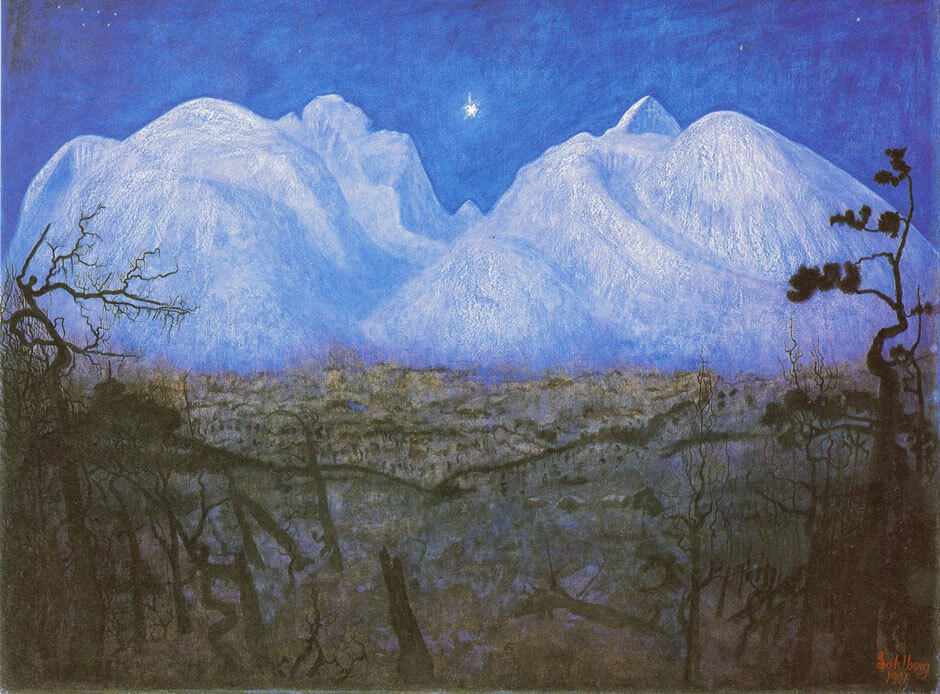

The purpose of the meeting was to deal with unfinished business. Seven years earlier, in January 1913, Harris and MacDonald had travelled to the Albright Art Gallery (now the Albright-Knox Art Gallery) in Buffalo, New York, to see the Exhibition of Contemporary Scandinavian Art. They returned to Toronto brimming with an almost evangelical fervour to paint Canada’s northern wilderness as the artists whose work they had just seen had done of their homeland. Everyone in their group was won over by this enthusiasm, including Thomson.

In addition, these artists (especially Harris and MacDonald) were strongly influenced by the drive in the United States, led by the poets Henry David Thoreau and Walt Whitman, to find spirituality in nature and to create a North American cultural movement separate from its European roots. In those same years, artists such as Robert Henri (1865–1929) were promoting a continental approach to landscape painting. Just as the future members of the Group of Seven were forming their ideas, they found themselves supported by a North American zeitgeist that was either rejecting European influences or insisting on a made-at-home style of expression.

In paintings such as Early Snow, 1915–16, Thomson had fulfilled the dreams of Harris, MacDonald, and their colleagues by helping them chart a path toward their goal of a Canadian national school of art. After Thomson’s sudden death in 1917, they mounted memorial exhibitions in his honour, first at the Arts Club in Montreal in March 1919, then at the Art Association of Montreal (now the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts), in Ottawa at the National Gallery of Canada, and, in February 1920, at the Art Gallery of Toronto (now the Art Gallery of Ontario). A week or two later, these men met together to form the Group of Seven.

Given his drift toward abstraction in works such as After the Storm, 1917, Thomson may not have continued to paint representative landscape scenes in the manner set out by the Group of Seven before and through the 1920s. As these men went on to dominate the Canadian art scene until the 1950s, in large part because of their own smart self-promotion and the nation’s sentimental longing for tradition in the wake of the two world wars, they intentionally looked away from such European influences as the Der Blaue Reiter, Cubism, the Fauves, Surrealism, Suprematism, Futurism, and Orphism. Had Thomson lived longer, these movements may have come to interest him.

Harold Town (1924–1990) suggests that the Group of Seven intentionally and intuitively ignored what was happening in the world of art elsewhere by looking inward instead of outward. In doing so these artists established a starting point and a vocabulary for a national school that endured. In Town’s words, “It was an implosion, not an explosion. And by looking inward it gave us an outward identity.”

The Artist and Nature

In his boyhood and in his last four years, Thomson lived close to nature. As a youth, he learned from his elderly relative, Dr. William Brodie, a well-known naturalist who worked in the biology department of what is now the Royal Ontario Museum, how to observe nature closely and appreciate its mystery. From 1913 on he moved to Algonquin Park as early as he could in the spring and stayed there until late in the fall. As a result, he painted the park in all seasons, weathers, and times of day.

By today’s standards, Thomson was not an environmentalist. Along with his friends in the future Group of Seven, he accepted logging in the forests, commercial fishing, mining, and the expansion of agriculture as essential to the growth of the Canadian economy. They all thought it inconceivable that Canada’s natural resources would ever be depleted, though they would no doubt be appalled by contemporary clear-cutting. In Timber Chute and Crib and Rapids, 1915, and Sandbank with Logs, 1916, Thomson painted scenes of logging and dams as part of the world around him. When fires swept through Algonquin Park, however, he was moved to record their fierce destruction in emotion-laden sketches such as Fire-Swept Hills, 1915, and Burned Over Land, 1916.

The Group of Seven, both before and after the First World War, was determined to present Canadians with a land that was pristine and inexhaustible—a wilderness Eden of the North. As a consequence, Thomson and his friends have been considered naturalists as well as spiritualists, sympathetic to the environment they portrayed with a boldness and vivid coarseness never achieved by previous artists. Thomson’s brash sketch Autumn Foliage, 1915, exemplifies these qualities well.

In recent years, however, a number of revisionist art historians have criticized Thomson and the Group of Seven for the status they claimed as originators of a new style of nationalist art. These men rejected Old World art styles, they say, yet the conventions they followed were European in origin. They travelled to the “unpopulated wilderness” to sketch, yet they ignored the lumbermen, miners, railway men, and vacationers who were already there, and especially the Aboriginal groups that had occupied these territories long before Europeans settled in the area.

Even Thomson’s vaunted skills as a canoeist and bushman have been exaggerated, particularly by his artist colleagues and admirers after his death. He was competent, but he certainly did not, as Frederick Housser wrote, “know the woods as the red Indian knew them before him.”

Canvases versus Oil Sketches

Throughout his career, Thomson produced four hundred or more small oil paintings on wood panels, canvas board, plywood, and cigar-box lids—in the way plein air artists sketching outdoors tend to do. These works were spontaneous, quickly executed sketches. They became, for him, like drawings—the most immediate and intimate expression of an idea, a thought, an emotion, or a sensation. They were based on his observations of a host of phenomena—sunsets, thunderstorms, and the northern lights—in Algonquin Park and around Georgian Bay.

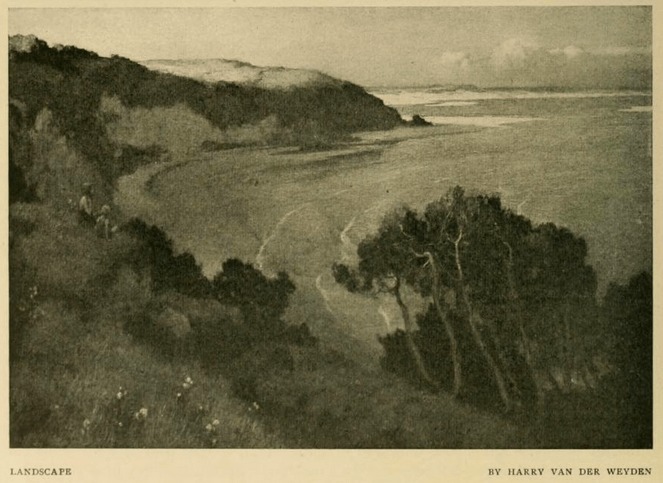

These “drawings in paint” have long been considered the core of Thomson’s work, given their general high quality. Most of them were not done as studies for larger canvases but as complete works in themselves. Thomson was satisfied with these small gems because he realized, as did his mentors J.E.H. MacDonald (1873–1932) and Lawren Harris (1885–1970), that they would not translate to a large canvas without losing the intimacy that characterizes them profoundly. Only a dozen or so, including The Jack Pine, 1916–17, and The West Wind, 1916–17, were ever realized as large canvases. Indeed, Thomson’s production of canvases was small: less than fifty in all, including awkward early works that are hardly part of the Thomson canon, such as Moose Crossing a River, 1911–12, and Northern Shore, 1912–13, which imitates a black and white reproduction Thomson found in The Studio magazine of Landscape, date unknown, by American artist Harry van der Weyden (1864–1952).

At one point Thomson said he wanted to produce an oil sketch a day—a kind of visual diary of Algonquin Park’s changing scenes, shifting with the weather and the seasons. They form an extensive suite of paintings with a constant theme: consistent in style and with a palette of strikingly original colours, the sketches were created with a specific intent and executed in a compressed time frame.

The Haystack paintings by Claude Monet (1840–1926) or the large cut-paper collages by Henri Matisse (1869–1954) serve similar ends. In Canadian art, the exquisite colour drypoints by David Milne (1881–1953) provide a coherent, related body of work. In literature, a body of related works might be a suite of poems, such as Shakespeare’s 154 sonnets linked by their theme of heartache, longing, and uncertainty, or Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Sonnets from the Portuguese, 44 sonnets written for her husband, Robert. Thomson’s small panels are, indeed, like love sonnets to the landscape of Algonquin Park and the idea of the North.

The Canadian Documentary Tradition

The documentary tradition has always been strong in Canada. It arrived with the British military in the mid-eighteenth century as it recorded Canadian topography in drawings, watercolours, and oils. Later visitors and settlers such as Paul Kane (1810–1871) travelled west, eager to paint Aboriginal peoples before, as everyone expected at the time, they disappeared entirely.

This documentary mindset was strong during Thomson’s time, and the Group of Seven wanted to show Canadians what their vast land truly looked like. Emily Carr (1871–1945) too was determined to record the First Nations villages, totem poles, and war canoes along the northwest coast and up the Skeena River before they vanished. European settlers who witnessed the precipitous decline in the Aboriginal populations—close to 90 per cent in places like Haida Gwaii (formerly the Queen Charlotte Islands)—had a compelling reason to believe that a visual record would shortly be the only way to know what had once existed there.

In a similar vein, A.Y. Jackson (1882–1974) painted the quaint villages along the St. Lawrence River and, in 1926, the Indian villages and totems along the Skeena River because he thought they would soon be gone, as in Night on the Skeena River. Even Marius Barbeau, the leading Canadian anthropologist of the day, believed that the extinction of the Aboriginal peoples across the continent was imminent.

Thomson didn’t abandon his urge to document as he developed what his patron Dr. James MacCallum called his “Encyclopedia of the North.” In Hot Summer Moonlight, 1915, he captured a common lake scene in Algonquin Park, though as a nocturne, not, as most artists preferred, by day. The sermon the future members of the Group of Seven wanted to preach to their fellow Canadians relied on representation. As David Milne (1881–1953), writing to Harry McCurry of the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, in April 1932, expressed it, “Tom Thomson isn’t popular for what aesthetic qualities he showed, but because his work is close enough to representation to get by with the average man.”

Judging by his sketches from the spring and summer of 1917, Thomson may have begun to realize there was a limit to the challenges and the rewards of Algonquin Park as a subject. If he was to respond honestly to his deepening sense of art’s power and of being an artist in touch with his times, he must have had intimations that he could not go on in that manner forever: he would have to acknowledge the Expressionist tendency toward abstraction and gestural painting that was already evident in his work, as revealed in one of his last sketches, After the Storm, 1917.

Photography

Thomson lived in the midst of the momentous transitions from art to photography, and on the cusp of the shift from representation to abstraction in painting. We know of his interest in photography because he lamented the loss of many rolls of exposed film when his canoe capsized twice on the Spanish River in 1912. The few photographs we have from him are ordinary snapshots, not aesthetic statements. His paintings, in contrast, quickly sweep past mere illustration and into strong emotional expression. Painters like Thomson don’t necessarily paint what they see: they paint how they want us to see and to feel.

In all the literature about the Toronto painters Thomson knew, there is no mention of any of them using cameras as an aid to memory. Rather, they all used small wooden panels to paint on-the-spot oil sketches of the landscape, and later developed larger canvases from some of them. The uncanny precision of Drowned Land, 1912, and a few other paintings, however, raises the question of whether Thomson did on occasion refer to a photograph he had taken. Even after his niece discovered, in 1967, a cache of forty of his photos, the question of this possibility is still not clearly answered. As things stand, not one of Thomson’s known photos relates to any of his paintings.

Thomson’s Death: Mystery or Myth?

Thomson’s death by drowning on July 8, 1917, was a shock to everyone who knew him and to many who had only heard of him. The tragic nature of his death erased any thought of the irony of this solitary loss thousands of miles from the battlefields of France and Belgium, where sixty-six thousand young Canadian men died in the First World War.

Thomson’s death was entirely unexpected. The weather that day was pleasant, and by 1917 Thomson had become a proficient canoeist who knew enough to handle himself safely. Despite his periods of doubt and melancholy, he was at the pinnacle of his career. He must have been uncertain at times because of his meteoric rise as an artist in just over four years, but there was no indication that he ever considered suicide. Nothing about the condition of his body suggested that he had taken his own life.

On the morning of July 8, Thomson was seen walking with Shannon Fraser, the owner of Mowat Lodge, and later heading off across Canoe Lake in his canoe. There were no reports of anyone following him, so the rumours of murder always seem to focus on the night before he was last seen. At the time no one mentioned the possibility of his having been in a fight that night or of the cut on his forehead causing his death.

The simplest explanation is therefore likely the correct one—that Thomson stood up in his canoe, lost his balance, and fell. He hit his forehead on the gunwale in the process, knocked himself out, and slipped into the water, where he drowned—as the coroner’s report confirmed. However, Roy MacGregor in his 2010 book Northern Light: The Enduring Mystery of Tom Thomson and the Woman Who Loved Him notes that he has uncovered additional information, including forensic evidence based on the skull found in what he considers Thomson’s grave overlooking Canoe Lake, that suggests Thomson may have been murdered. His research will need to be considered by any of Thomson’s future biographers.

Regardless, what remains is not a mystery but a rich legacy, full of abiding meaning and satisfying pleasure for everyone who looks at the paintings. They, rather than vacuous speculation about the manner of his death, are the objects Thomson would want viewers to study and enjoy. Of all the recent representations of Thomson in words and in art, perhaps the canvases Swamped, 1990, and White Canoe, 1990–91, by the renowned painter Peter Doig (b. 1959), best capture the myth and the mystery. Here Doig, who spent his childhood and youth in Canada, alludes to the iconic 1914 photograph of Thomson sketching from his canoe, except that, in his images, the ghostly white canoe is empty.

Enduring Popularity

Artists of every stripe and persuasion, whether landscape painters or not, have acknowledged that Thomson gave Canada a galvanizing set of icons that largely define the Canadian visual identity, as many people like to think of it. Poets have written about his work; playwrights have dramatized his life; films, both documentary and fictional, have presented his achievements; musicians—classical and popular—have composed songs with references to him; and one of the plays about him, Colours in the Storm, has come back to life as a musical. In 2013, when Kim Dorland (b. 1974) became the first artist-in-residence at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection, Kleinburg, Ontario, he responded directly to some of Thomson’s paintings in his works. In the exhibition You Are Here: Kim Dorland and the Return to Painting, the images by the two artists were shown side by side.

Sherrill Grace, a respected scholar, writes in Inventing Tom Thomson that Thomson is a “haunting presence” for Canadian artists. For creators in all disciplines, she says, he “embodies the Canadian artistic identity.”

In addition to the world of contemporary visual art, Thomson has made an impression on popular culture. The rock group The Tragically Hip refers to Thomson in their song “Three Pistols.” The film The Far Shore, by artist Joyce Wieland (1930–1998), was her panegyric to Thomson and a statement of her parallel love for Canada’s wilderness. Poets, including Robert Kroetsch, Henry Beissel, George Whipple, Kevin Irie, and Arthur Bourinot, have written lamentations about him.

The most recent grand tribute to Thomson and his work is the spectacular 2011 film West Wind: The Vision of Tom Thomson, directed by Michèle Hozer and produced by Peter Raymont.

Thomson and the Art Market

Although Thomson sold relatively few paintings during his lifetime, the prices were more than satisfactory for someone with low expectations: $500 for Northern River, 1914–15, was a handsome sum at that time. He was happy to get $20 for a small panel, though more commonly he gave them away as gifts to friends who admired them. Even for a bachelor, Thomson made but a meagre living. When he died, he left a dozen or so canvases and a large stack of oil sketches unsold.

After Thomson’s death, Dr. James MacCallum despaired of selling even this modest number of works, given the frugal appetites of Canada’s collectors for contemporary work. Yet, within a few years, MacCallum, Lawren Harris (1885–1970), J.E.H. MacDonald (1873–1932), and A.Y. Jackson (1882–1974) sold off a sizable number of the canvases and sketches stored in the Studio Building in Toronto. Around 1922 Jackson estimated that, of the 145 sketches there, some twenty-five were worth perhaps $50 each, fifty were worth $40 each, and for the other seventy, $20 each would be a good price. Harris advised his friends the Laidlaw brothers to add Thomson to their collections, and soon after he told MacCallum that they had purchased twenty sketches for a total of $1,000.

All told, Thomson’s prices doubled in the five years after he died—and they have doubled every few years thereafter. In 1943 MacCallum donated his huge holding of Thomson’s works, eighty-five in all, to the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, to which he had, in 1918, sold twenty-nine oil sketches.

Because Thomson’s canvases nearly all found their way into public collections soon after his death, and there were so few in any case, the market in his work has mostly been the sketches. The highest price for a Thomson sketch, Early Spring, Canoe Lake, 1917, is $2,749,500, achieved by Heffel auction house on November 26, 2009. A canvas, were a good one to become available, would likely eclipse Paul Kane’s record of $5.1 million for a Canadian painting. But today only four or five canvases remain in private hands.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements