Tom Thomson (1877–1917) is one of the greatest artists Canada ever produced, yet much of his life remains shrouded in mystery. He began as an itinerant engraver and after several years emerged as a gifted and innovative painter. This transformation started in 1909, when he found himself surrounded by a group of talented and ambitious artists in Toronto. Although Thomson was older than most of them, he learned quickly and was soon setting an example that surpassed them all. His career as an artist lasted a scant five years, but his legacy endures.

Boyhood Years

Thomas John Thomson was born on August 5, 1877, in Claremont, Ontario, a hamlet-sized farming community about fifty-five kilometres northeast of Toronto. He was the sixth child and the third son of John Thomson and Margaret J. Matheson, who had ten children in all. Documentary information about his life is sparse, though a few details were recorded in anecdotes from people who knew him.

When Thomson was two months old, his parents moved to a farm in Leith, on the Bruce Peninsula. The closest town was Owen Sound, a major shipbuilding centre and a bustling Great Lakes port. He grew up in a large music-loving family that read widely (his mother saw to that) and learned the pleasures and excitement of hunting and fishing (his father’s pastimes). Most of the Thomson children liked to draw and paint, but Tom was no prodigy. The children also sang in the church choir and performed in the local band. Later in Toronto, Thomson took singing lessons and played the mandolin.

At some point Thomson was taken out of school for a year because of illness, which was described at the time as weak lungs or inflammatory rheumatism. As he wandered about in the hardwood and coniferous forests near his home, he became familiar with woodland lore. He also had the opportunity during family visits to collect specimens with Dr. William Brodie, his father’s cousin, who was a well-known naturalist. In this way he learned to observe nature closely and respect its mystery. Once he recovered, he returned to his studies and may well have finished high school. Standing six feet tall, he was an easygoing, agile, and handsome young man.

Early Adult Years

When Thomson turned twenty-one in 1898, he, like all his siblings, received an inheritance from his grandfather, after whom he had been named. His share was approximately $2,000. Although it was a large sum at the time, there is no record about where the money went or how quickly he spent it. The following year he apprenticed at a foundry and machine shop in Owen Sound but moved on after eight months.

Thomson went to Chatham, in southwest Ontario, and enrolled at the Canada Business College. Again his patience wore thin: he left after eight months and returned home for the summer of 1901. Next he headed to the Pacific Northwest, where his oldest brother, George, and a cousin had set up the Acme Business College in Seattle. Thomson worked briefly as an elevator operator at the Diller Hotel, near the waterfront. Within the year his brothers Ralph and Henry arrived in the city to join the clan.

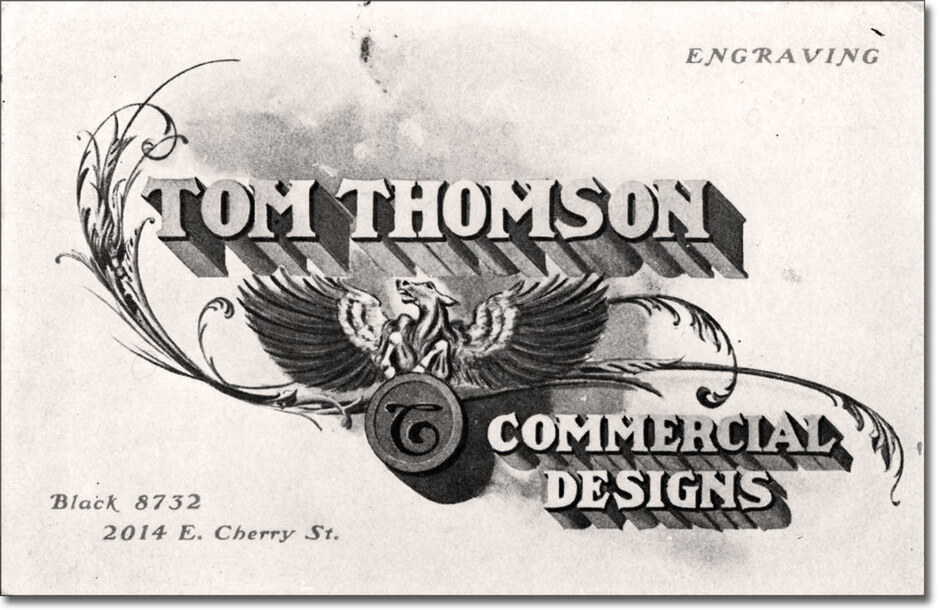

In 1902, after six months’ study at the Acme Business College, Thomson was hired as a pen artist, draftsman, and etcher at an engraving firm, Maring & Ladd (later Maring & Blake), which specialized in advertising and three-colour printing. He had learned calligraphy at the Canada Business College, and this appointment indicates that he was a quick study, with enough raw talent in lettering, drawing, and painting to produce business cards, brochures, and posters for clients. Around this time, many artists earned a good livelihood as graphic artists.

Thomson soon switched to the local Engraving Company, where, because of his skills, he was offered higher wages. However, he suddenly returned to Leith at the end of 1904, likely because his proposal of marriage had been rejected by the teenage Alice Lambert, the intense but imaginative daughter of a clergyman. Lambert went on to write romantic novels, one of which featured a young girl who was wooed by an artist and refused him, to her later regret.

Graphic Design in Toronto, 1905–13

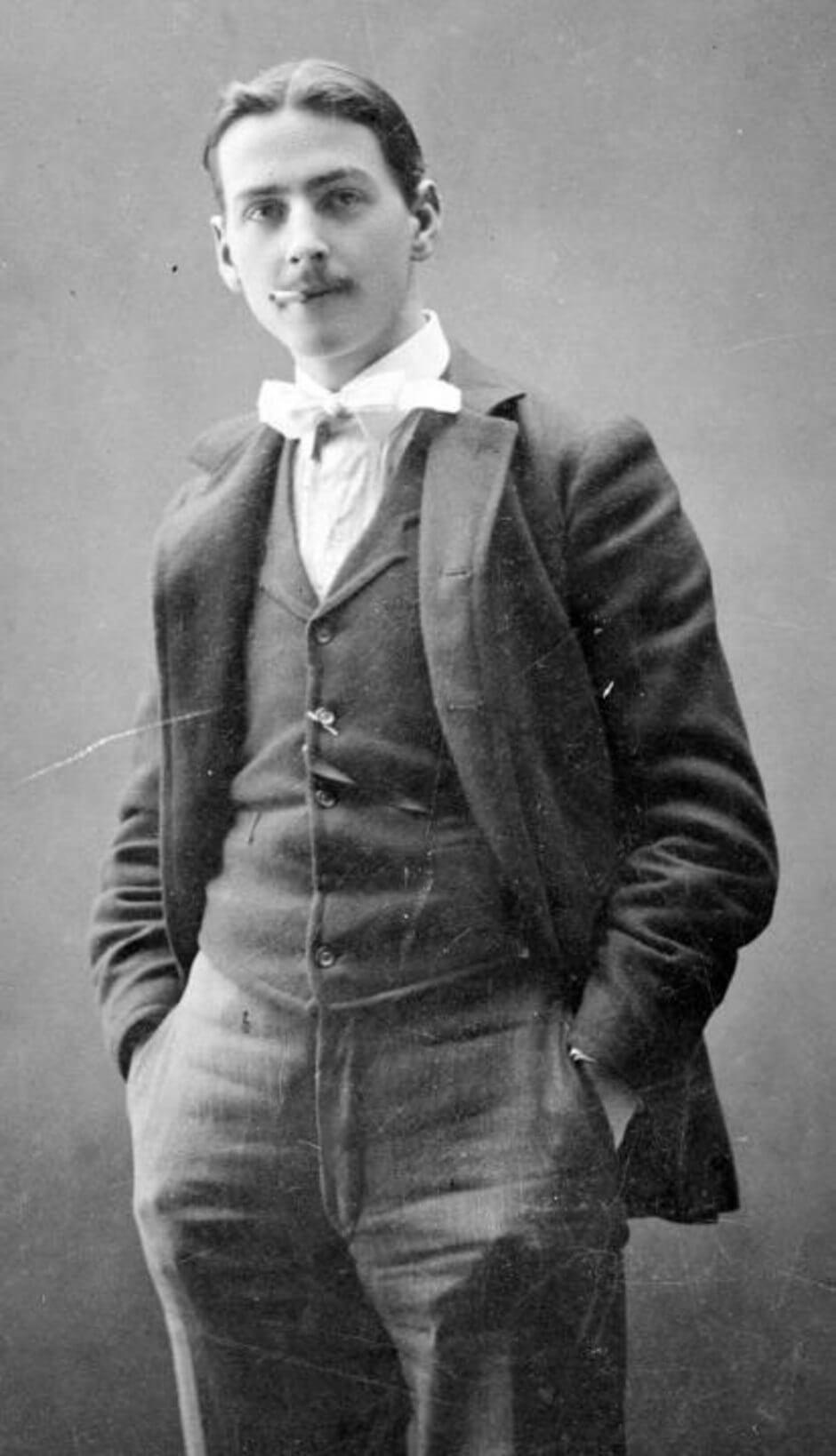

Thomson moved to Toronto in the summer of 1905 and settled into the first of the many boarding houses he would live in over the coming years. He got a job at Legg Brothers, a photo-engraving firm, and sometimes visited his family on weekends. In his free time he read books (often poetry) and attended concerts, the theatre, and various sporting events. A few pictures taken at this time show him smartly dressed—quite the dandy. Women liked him, though at times he could be moody and quarrelsome and drink too much. Many of his friends and colleagues later described him as periodically erratic and sensitive, with fits of unreasonable despondency. Throughout his life, he was attracted to quality items—silk shirts, meals in elegant restaurants, fine pipes and tobacco. Even when he reduced his possessions to a minimum for a roving life of camping and canoeing in Algonquin Park, he still bought the best paints, brushes, and wood panels on the market.

In his early days in Toronto, Thomson also seems to have taken night classes from William Cruikshank (1848–1922), a British artist well trained in the academic tradition who taught painting at the Central Ontario School of Art and Industrial Design (later the Ontario College of Art, now OCAD University). Although Thomson’s friends were later critical of Cruikshank’s teaching, calling him a “cantankerous old snorter” among other unflattering names, Thomson may have learned some useful techniques from him.

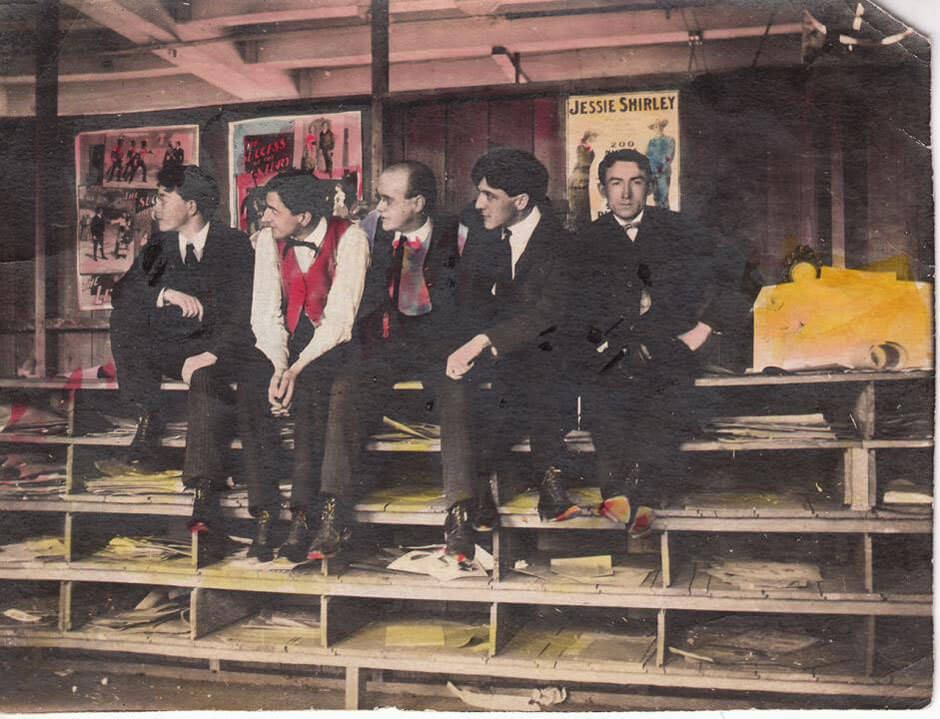

Around the beginning of 1909, Thomson landed at Toronto’s leading commercial art and engraving firm, Grip Limited, where he specialized in design and lettering work. Albert Robson (1882–1939), the art director, recalled that when he hired Thomson, “his samples consisted mostly of lettering and decorative designs applied to booklet covers and some labels.” Grip produced the usual array of posters for railways and hotels, mail-order catalogues, and real estate brochures, but Thomson’s life immediately began to change because of the people he met there. The senior artist was J.E.H. MacDonald (1873–1932), who encouraged his staff to foster their talents by painting outdoors in their spare time—in the city’s ravines and the nearby countryside. Robson obviously appreciated artists, and he hired Thomson on a hunch. Over the next three years he hired Arthur Lismer (1885–1969) and Fred Varley (1881–1969), both fresh from England, and Franklin Carmichael (1890–1945). Through MacDonald, Thomson met Lawren Harris (1885–1970) at the Arts and Letters Club, a convivial meeting place and eatery for men interested in literature, theatre, architecture, and art. At that point Thomson’s circle of friends and influences was almost complete: except for Robson, these men were all future members of the Group of Seven.

When Robson moved to Grip’s main competitor, Rous and Mann Limited, in the fall of 1912, most of his loyal staff, including Thomson, followed him. Inevitably they found much of their work boring, but they appreciated the freedom Robson gave them to take art classes or leave for extended painting trips during the summer. Very few examples from Thomson’s years at Grip or Rous and Mann can be firmly attributed to him, though the pieces that exist reveal some of the elements and decorative patterns that marked his later paintings. One beautifully lettered and illustrated verse by Robert Burns exists in at least three versions (c. 1906, 1907, and 1909). An untitled ink drawing of a lakeshore scene from around 1913, like so many of his sketches, depicts a low range of hills across the lake, with a few trees in the foreground.

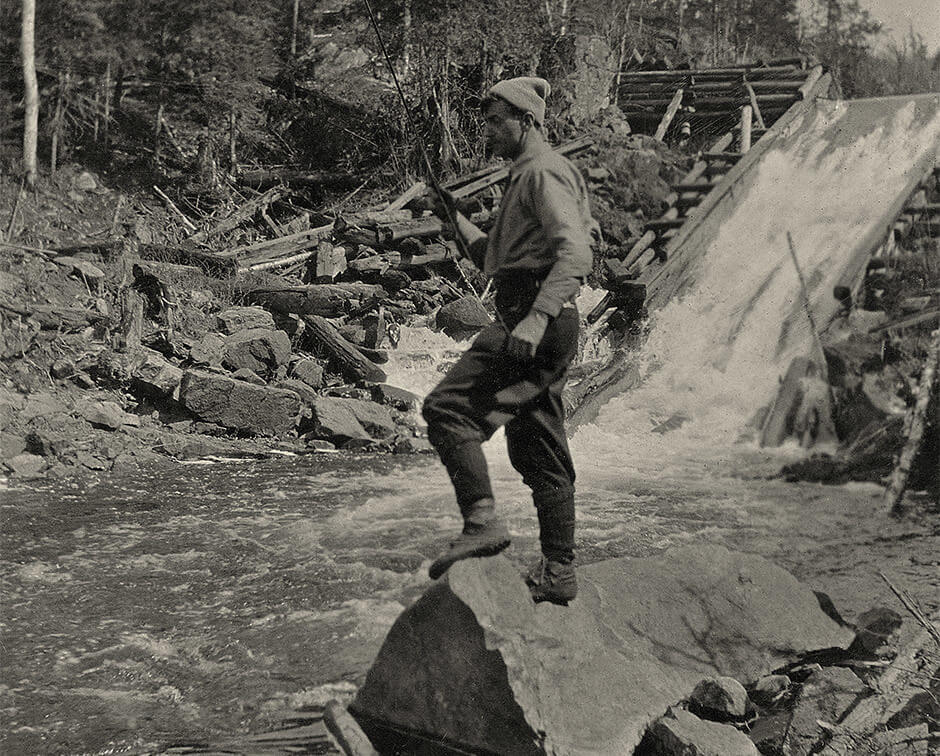

Discovering Algonquin Park

In 1912 Thomson bought an oil-sketching kit for painting outdoors. With a Grip colleague, Ben Jackson (1871–1952), he took his first canoe trip early that spring in Algonquin Park, an enormous recreation and forested area criss-crossed by rivers and streams about three hundred kilometres northeast of Toronto. To accommodate the wealthy holidaymakers and outdoors types who flocked there by rail, it offered a mix of posh hotels and modest lodges; hikers and canoeists could camp by one of the myriad lakes. In the backwoods, as they cut numerous trails and roads, teams of loggers had built dams, sluices, and chutes. Thomson recorded one of these decaying dams in Old Lumber Dam, Algonquin Park, 1912—a sketch that illustrates his transition from the formalities of commercial art to a more imaginative style of original painting.

In the fall Thomson set out on a two-month canoe trip with another artist friend from Grip, William Broadhead (1888–1960), up the Spanish River and into the Mississagi Forest Reserve (now an Ontario provincial park). There they explored the rough and beautiful terrain north of Manitoulin Island and Georgian Bay while Thomson honed his canoeing skills. They had two bad spills, however, in which he lost almost all his oil sketches and several rolls of exposed film.

The precision of Drowned Land, 1912, reveals the rapid progress Thomson was making as an artist at this time. To cap this astonishing year in which the late-blooming Thomson began the transition from commercial artist to full-time painter, in October J.E.H. MacDonald (1873–1932) introduced him to Dr. James MacCallum, a professor of ophthalmology at the University of Toronto who visited the Ontario Society of Artists exhibitions and was particularly interested in landscape paintings. Just over a year later, in the fall of 1913, MacCallum introduced Thomson to A.Y. Jackson (1882–1974)—a well-trained artist who had recently returned from his third visit to France. There he had studied at the Académie Julian and travelled widely on painting trips in Italy, France, and England. Harris and MacCallum had been impressed by Jackson’s painting The Edge of the Maple Wood, 1910, which they regarded as a fresh approach to the Canadian landscape and which Harris purchased. Encouraged by their invitation, Jackson moved from Montreal to Toronto—and in due course became a member of the Group of Seven.

Recognizing the talent of these two unknown artists, Jackson and Thomson, MacCallum offered to cover their expenses for a year if they would devote themselves full time to painting. As he later recalled, when he first saw Thomson’s sketches from 1912, he recognized their “truthfulness … they made me feel that the North had gripped Thomson,” just as it had gripped him too as a boy. Both men accepted MacCallum’s offer. Although Thomson did not realize it at the time, he had found in MacCallum a patron, a staunch supporter, and a guardian of his paintings after his death.

Thomson’s Early Paintings

In 1913 Thomson began going with colleagues from Rous and Mann on weekend painting trips to Lake Scugog or other rural and sparsely inhabited places not far from Toronto. Although his early efforts, such as Northern Lake, 1912–13, or Evening, 1913, are neither sophisticated nor technically outstanding, they show more than average ability in their composition and handling of colour. When they saw works such as View from the Windows of Grip Ltd., c. 1908–10, his astute friends began to realize that he was not the amateur artist he thought himself to be.

In January that year Lawren Harris (1885–1970) and J.E.H. MacDonald (1873–1932) had visited the Exhibition of Contemporary Scandinavian Art at the Albright Art Gallery (now Albright-Knox Art Gallery) in Buffalo. They were struck by the similarities between the raw Scandinavian landscape depicted in the paintings there and Canada’s, and they returned with a catalogue annotated with their observations. This show proved to be a turning point in Canadian art: from then on, these influential painters imbued their colleagues, including Thomson, with the ambition to create a national art movement for Canada, based on the country’s unspoiled “northern” character. Their enthusiasm culminated in the formation of the Group of Seven in March 1920.

Significantly, not one of these friends attended another exhibition that took place in New York in February–March 1913: the Armory Show (formally the International Exhibition of Modern Art), which brought the most avant-garde modernist art of Europe and America to New York and caused a sensation. Their focus was indeed inward; yet this attitude may be exactly what, in the end, produced an outward identity for Canada.

On his way back to Toronto that same fall, Thomson stopped in Huntsville and may have visited Winifred Trainor, whose family had a cottage on Canoe Lake in Algonquin Park. Later, she was rumoured to be engaged to Thomson for a marriage in the fall of 1917, but the records are thin, and she remains one of the mysteries in his life story.

Painting Full Time

During his year of support from Dr. James MacCallum in 1914, Thomson became hooked on painting. Initially he had been reluctant to accept the doctor’s offer, but, encouraged by the sale of Northern Lake, 1912–13—a work he had shown in the 1913 spring exhibition of the Ontario Society of Artists—for $250 to the Ontario government, he decided he would devote his life to making art. He settled into a regular pattern: every spring he headed north to Algonquin Park as early as possible and stayed there as long as he could into the fall.

Thomson spent the three to four winter months in Toronto painting canvases in the Studio Building at 25 Severn Street. Planned and financed by Lawren Harris (1885–1970) and MacCallum, this structure was built in 1913–14 and comprised six studios, each with large north-facing windows, storage racks, and a small sleeping mezzanine. Thomson and Jackson moved into Studio 1 in January 1914, before construction was complete. They shared the rent of $22 a month until Jackson joined the army at the end of the year, though both of them were away on painting trips during much of that time. By early 1915, given his plan to spend two-thirds of every year away from Toronto, Thomson had decided to move into the shed behind the Studio Building. Harris fixed it up for him with a new roof, floor, studio window, stove, and electricity and charged him rent of a dollar a month.

A Startling Debut

Thomson split the spring and summer of 1914 three ways: first in Algonquin Park (April–May), then in Georgian Bay (June–July), and finally in the park again (August–mid-November). He and Arthur Lismer (1885–1969) painted together in May, and during his two months in Georgian Bay he explored the area around Dr. James MacCallum’s cottage at Go Home Bay.

Although the war in Europe erupted in August, Thomson and A.Y. Jackson (1882–1974) met up for an early fall canoe trip in the park, where they were joined on their return by Lismer and Fred Varley (1881–1969), along with their English wives. This trip marked the first time that three members of the future Group of Seven painted together, and the only occasion they worked with Thomson. In their eyes he was a real outdoors expert: they were astounded by his ability to catch fish for the evening meal, cook over an open fire, set up camp, and navigate the rapids in a canoe.

In terms of his painting career, 1914 was a turning point for Thomson. The National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, under director Eric Brown (and advised by board member Lawren Harris [1885–1970]), began to acquire Thomson’s work, first Moonlight, 1913–14, from the Ontario Society of Artists exhibition for $150; then Northern River, 1915, the following year for $500; and a year later Spring Ice, 1915–16, for $300. Such recognition was remarkable for an emerging, unknown artist, though the money he received was not sufficient to live on. Thomson, however, never paid much attention to managing his career. He didn’t even give titles to most of his paintings or date them. After Thomson’s death, MacCallum in particular looked after those details.

Everyone expected that the war in France would soon end, but as the months wore on, Jackson decided to enlist, followed by Varley and Harris. Thomson, although he had just turned thirty-seven, attempted to join up more than once, but he was not accepted—apparently because of his flat feet. Some of the other residents in Algonquin Park opposed his patriotic views about the war, and at times they argued angrily about Canada’s involvement in the conflict. Thomson expressed his anguish about the war in sketches such as Fire-Swept Hills, 1915, which echoed the turmoil, destruction, and death that was sweeping across France and Belgium.

Gathering Momentum, 1915

Thomson spent the spring and summer of 1915 on long trips in different sections of Algonquin Park. A new cedar-strip canoe and a silk tent added to his pleasures and comforts, and his small oil sketches on wood panels mounted up impressively. He made little effort to sell them, and he generously gave many away to people who admired them. Only the canvases he sold brought in some money. To make ends meet, once Dr. James MacCallum’s year of support had ended, he worked as a fire ranger or fishing guide whenever he could.

In the fall Thomson joined J.E.H. MacDonald (1873–1932) at MacCallum’s cottage to measure the walls for a series of seven commissioned decorative panels. He then returned to the park, where he remained until the weather drove him back to Toronto at the end of November. He painted MacCallum’s panels that winter, but when it came time to install them in the spring, they didn’t all quite fit and four were returned to Toronto. MacCallum bequeathed the panels to the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, in 1943, along with eighty-five of Thomson’s paintings and oil sketches from his collection.

The sketch Thomson made for Opulent October, 1915–16, that fall is a prime example of his increasing artistic power. The sketch itself is not particularly brilliant, but over the winter, using it as a model, Thomson recreated it as a good-sized canvas—a process that proved to be a breakthrough for him. Once he discovered he could make a gigantic leap from a sketch to a completely different treatment of the subject, his full range of abilities—mental, aesthetic, technical, and emotional—were liberated to create his most remarkable works.

At Full Speed, 1916

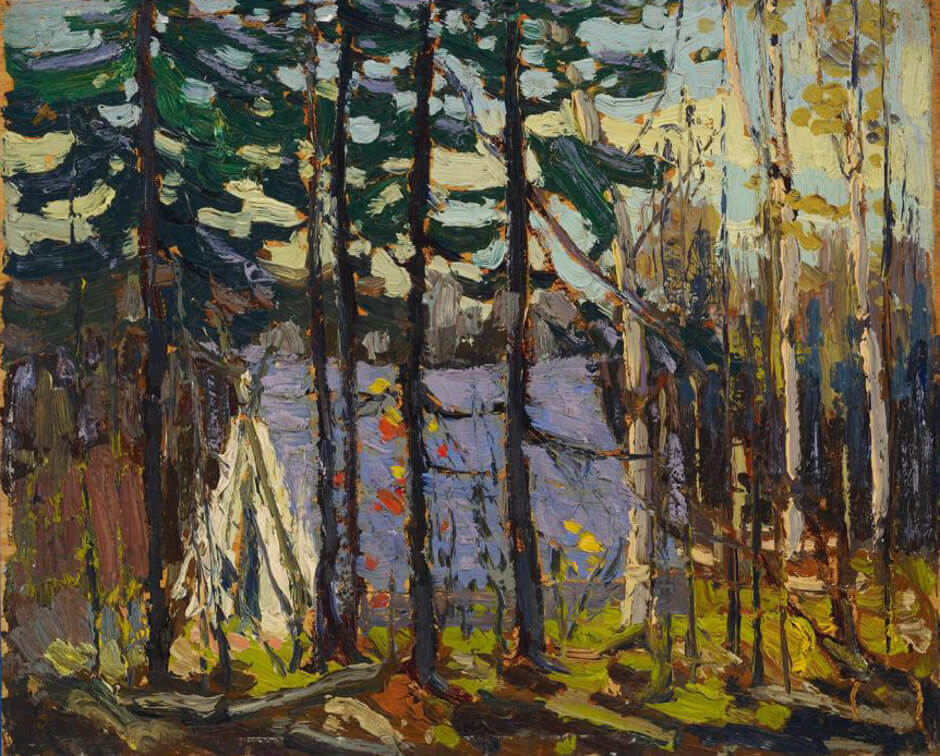

Lawren Harris (1885–1970) and Dr. James MacCallum joined Thomson for an early spring canoe trip in Algonquin Park in 1916, after which he worked for a month or more as a ranger at the eastern end of the park. Again, and despite such distractions for the artist, Thomson’s stack of sketches continued to grow, diverse in subject matter, varied in composition, vivid in colour, thick with vigorously applied pigment, and inspired by the landscape and the region he understood so deeply.

Over the winter of 1916–17, Thomson, with strong encouragement from Harris, J.E.H. MacDonald (1873–1932), and MacCallum, enjoyed the most productive months of his life. He tackled ten major canvases in all, culminating in his two greatest achievements on canvas: The West Wind, 1916–17, and The Jack Pine, 1916–17. Both paintings were based on small sketches he had painted in the spring of 1916.

Final Spring, 1917

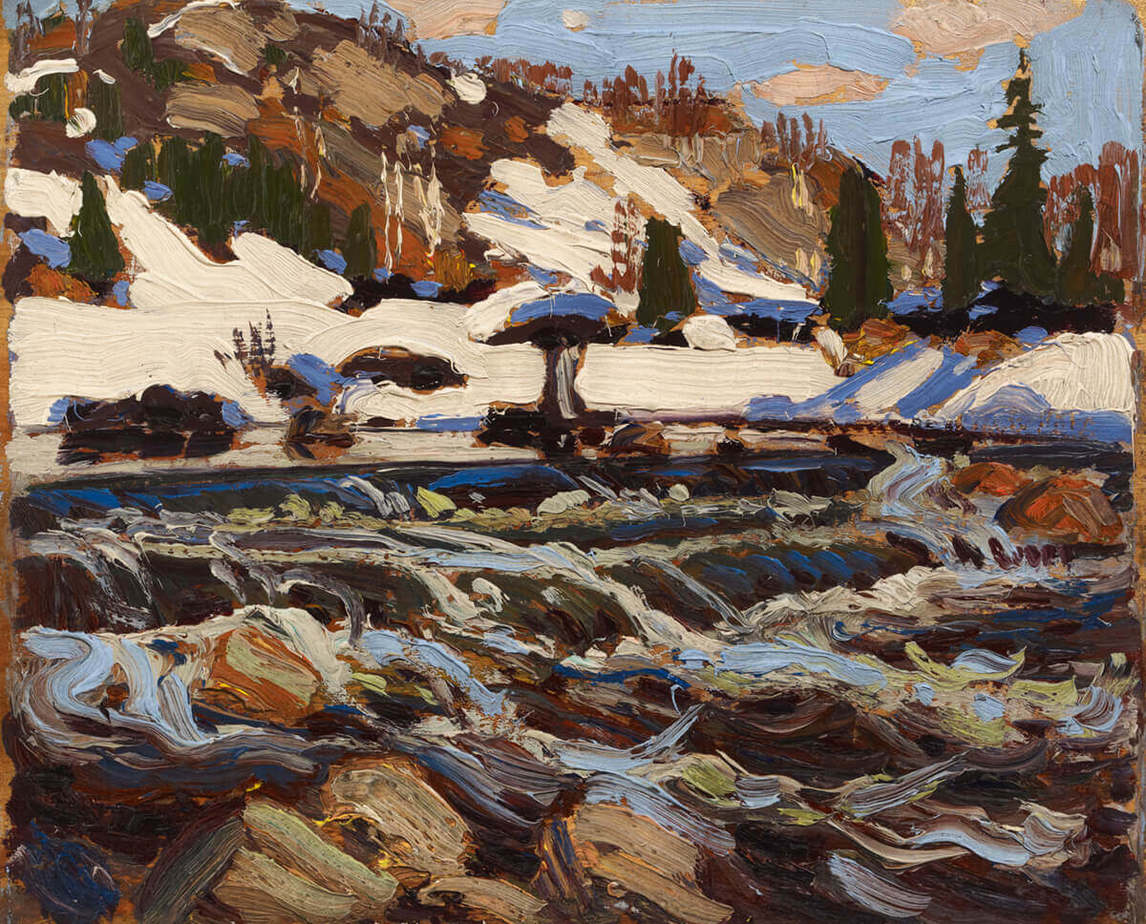

The sketches from the spring and early summer of 1917 confirm that Thomson had risen to an even higher artistic plateau. His work from this period, such as The Rapids, 1917, demonstrates the assured hand with which he created his compositions; through his colours and treatment of the atmosphere, viewers can sense the chill or the warmth in the air—as in Path behind Mowat Lodge, spring 1917, or Tea Lake Dam, summer 1917. His brush strokes became bold and expressive, and he seemed to be moving inexorably toward abstraction.

Dr. James MacCallum described Thomson’s paintings as an “Encyclopedia of the North,” a visual account of the terrain in every season, time of day, and kind of weather. Algonquin Park, much as Thomson loved it, however, could not remain an infinite source of inspiration if he was to continue to grow in stature as an artist. That spring of 1917, Thomson seems to have been eager to extend his exploration of northern subjects—and his treatment of them in his paintings. He had just had the most productive period of his life in his studio in Toronto, and his sketches show clearly that he was brimming with new ideas about what he could capture and reveal in his forthcoming paintings.

A Mysterious Death

On the morning of July 8, 1917, several people saw Thomson with Shannon Fraser, the owner of Mowat Lodge where Thomson often stayed, walking toward the Joe Lake dam. Mark Robinson, the park ranger, noted in his diary that Thomson “left Fraser’s Dock after 12:30 pm to go to Tea Lake Dam or West Lake.” Thomson’s body was found in Canoe Lake eight days later, on July 16, and was immediately interred in a nearby grave. The Thomson family sent an undertaker from Huntsville to remove the body and transport it to Leith, for burial in the family plot at the cemetery there. The official cause of death was given as accidental drowning, though a four-inch cut on Thomson’s right temple was noted.

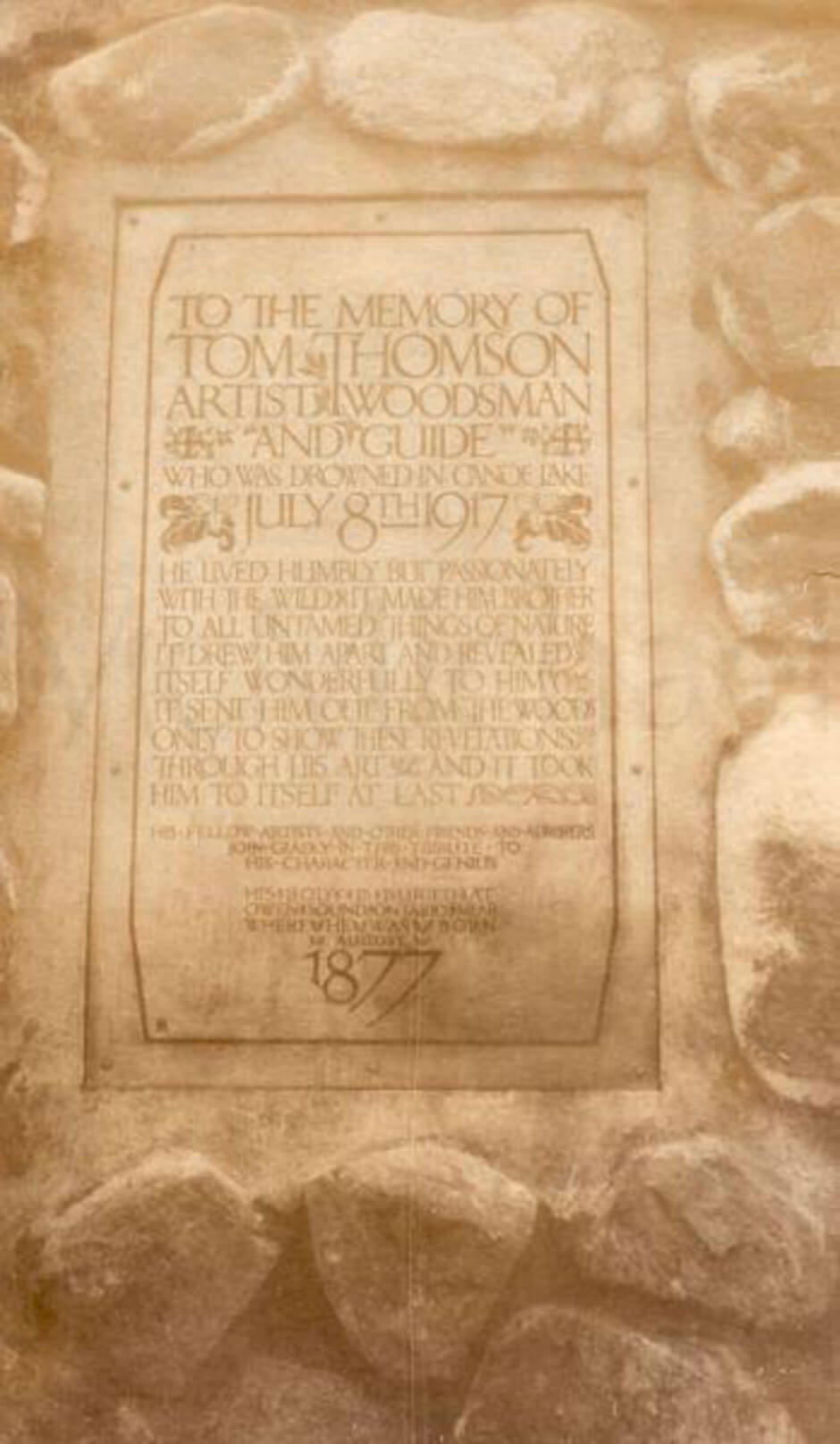

J.E.H. MacDonald (1873–1932) designed a bronze plaque to commemorate the life of his close friend and fellow painter. Soon after, he and the artist J.W. Beatty (1869–1941) set it into a cairn on a promontory overlooking Canoe Lake. It reads:

TO THE MEMORY OF

TOM THOMSON

ARTIST, WOODSMAN

AND GUIDE

WHO WAS DROWNED IN CANOE LAKE

JULY 8TH, 1917.

HE LIVED HUMBLY BUT PASSIONATELY

WITH THE WILD. IT MADE HIM BROTHER

TO ALL UNTAMED THINGS OF NATURE.

IT DREW HIM APART AND REVEALED

ITSELF WONDERFULLY TO HIM.

IT SENT HIM OUT FROM THE WOODS

ONLY TO SHOW THESE REVELATIONS

THROUGH HIS ART AND IT TOOK

HIM TO ITSELF AT LAST.HIS FELLOW ARTISTS AND OTHER FRIENDS AND ADMIRERS

JOIN GLADLY IN THIS TRIBUTE TO

HIS CHARACTER AND GENIUS.HIS BODY IS BURIED AT

OWEN SOUND ONTARIO NEAR

WHERE HE WAS BORN

AUGUST

1877.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements