Born in a poor, segregated Black suburb of Detroit, Tim Whiten (b.1941) overcame oppressive economic and social conditions to become an award-winning artist and educator who inspired generations of Canadian artists. From an early age, his parents emphasized the importance of education, service, and a strong spiritual foundation, which shaped his unwavering “belief in things beyond oneself, beyond the visible world.” For more than five decades, he has drawn from his ancestral heritage, mysticism, and philosophy to produce powerfully evocative cultural objects and ritual performances that explore the nature of the human condition. Endowed with symbolic and visceral impact, they ignite the mythic imagination, transcending time and place.

Early Life in Michigan

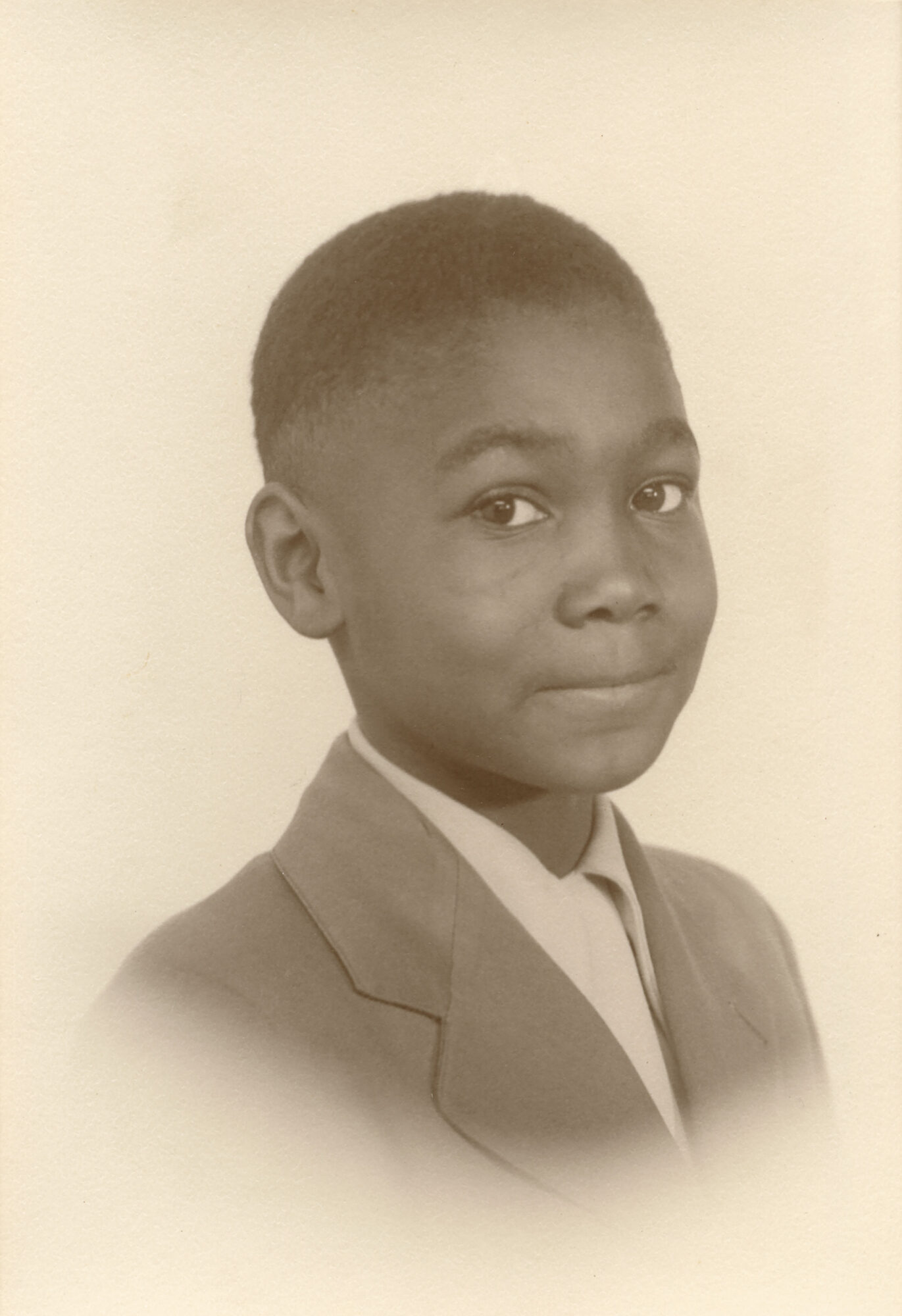

Grover Timothy (Tim) Whiten, the third son and youngest child of Tom and Mary Emma Whiten, was born on August 13, 1941, in Inkster, Michigan, a town southwest of Detroit. Tom Whiten, one of five siblings, was born in 1894 on a plantation in Mount Meigs, Alabama. After working as a sharecropper with his brother, he left Alabama at the age of thirteen for Chicago, where he took a job with the railroad as a porter. He later moved to Detroit, finding employment as a labourer at the Ford Motor Company (Ford), advancing through the company’s ranks until his retirement in 1959.

Tom’s curiosity and ambition were an inspiration to his young son. Tom became a licensed carpenter and a stone mason, skills he developed with the support of fellow members of the African American chapters of the Masonic order. While he possessed only a sixth-grade education, he was fluent in five languages (Greek, Italian, Polish, Czech, and English), understood higher mathematics, and played several instruments proficiently. He had hoped to become a court interpreter but was considered an unacceptable candidate because of his race. Tom was also a respected community leader, holding positions such as Deacon of the Springhill Baptist Church and President of the Planning Commission responsible for the stewardship of Inkster Township in its formation as a city. In honour of his civic contributions, a subdivision bears his name.

Tim Whiten’s mother was a role model too. Mary Emma Glaze was born in Tignall, Georgia, in 1914, and grew up in a family of sharecroppers. At the age of fourteen, when her parents died, she was placed in the care of her elder sisters. Two years later, she travelled north to Michigan to work as a servant in residential homes until she married Tom, twenty years her senior. Mary took night courses toward a high school diploma, which she earned in 1958, and gained skills as a butcher through a co-operative store in Inkster. She worked as a manager of a supermarket meat department and later as a pharmacist’s assistant in Sinai Hospital of Detroit until her retirement. Mary also became a matriarch of the local Baptist church and served on its outreach committees.

Tom and Mary moved to Michigan in the early 1900s as part of the Great Migration, during which millions of African Americans from the rural southern states travelled to the urban north, Midwest, and west to build a better life for themselves and their families. In Michigan, they found solace from the hardships of life in the southern states. They built a home for themselves and their family, making ends meet by harvesting vegetables from their garden; sewing their own clothing; and butchering, salt-curing, and hanging meat in their attic. Tom’s fluency in various languages helped foster friendships with their culturally diverse neighbours and his colleagues from Ford, who lent their skills to help build the Whitens’s houses in Inkster.

Overcoming the limitations into which you are born and creating opportunities for advancement were fundamental values held by the Whiten family. As Tim observes, “I firmly believe that many things in childhood identify the realities of who and what we really are.” These familial experiences inform the artist’s practice. Later works pay tribute to his parents and the enduring influence of their attitudes toward labour and craftsmanship, including T After Tom, 2002, a partial glass brick wall and a series of glass hand tools, and Mary’s Permeating Sign, 2006, a glass rolling pin resting on a pillow.

Tim was born at 3502 Irene Street, a two-bedroom house in Inkster. He was delivered by Dr. Young, the family physician who had delivered Tim’s elder brothers, Leonard and Jim. The artist recalls what was said to be his father’s proposal to his mother: “‘Mary, if you marry me, I’ll build you a house.’… It was a labour of love and just before it was fully complete, they were married.” Tom later added a grape arbour, fruit trees, and a vegetable garden, as well as an adjoining garage for his car. This was the first of two homes he built for his family; the second was a three-bedroom brick house on the same street where, for the first time, Tim had a bed of his own instead of sharing with his brothers.

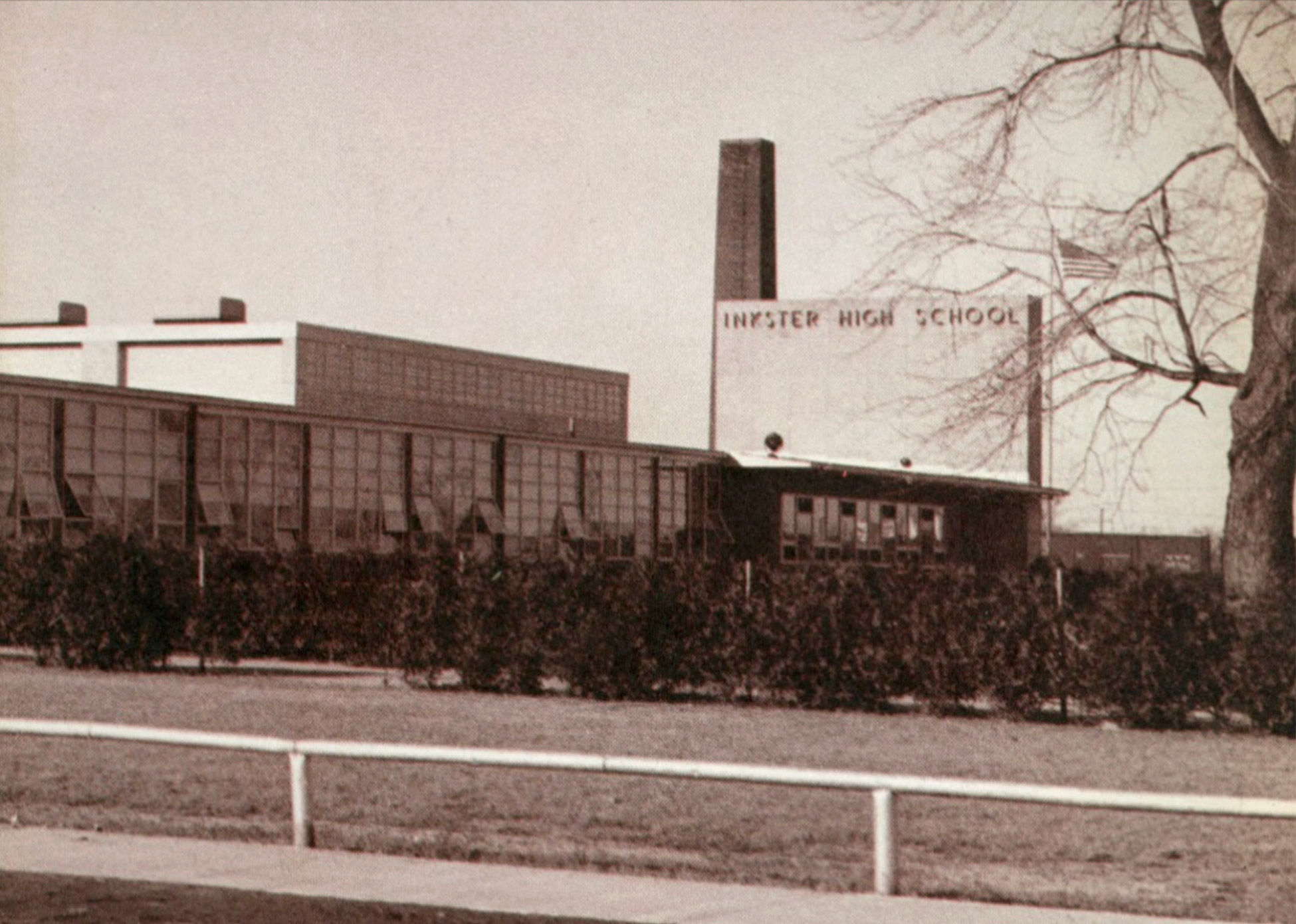

Ford helped establish Inkster as a working-class subdivision of Detroit for its predominantly Black employees and their families in the 1930s. Reflecting on the formation of his hometown, the artist comments: “Ford had a large contingent of Black workers employed at its Rouge Factory in Detroit. Dearborn, Michigan, was the closest town to the factory but it was where the executives of the company lived. It was populated by all whites who had no intention of living with Blacks. The solution was for Ford to help instigate a settlement for its Black workers in order to prevent them from living in Dearborn. I remember a newspaper article written by the then-mayor of Dearborn in which he wrote, ‘We don’t want your little hottentots in our city.’ Thus, Inkster was created, segregating the Black population, many who worked for Ford Motor Company.”

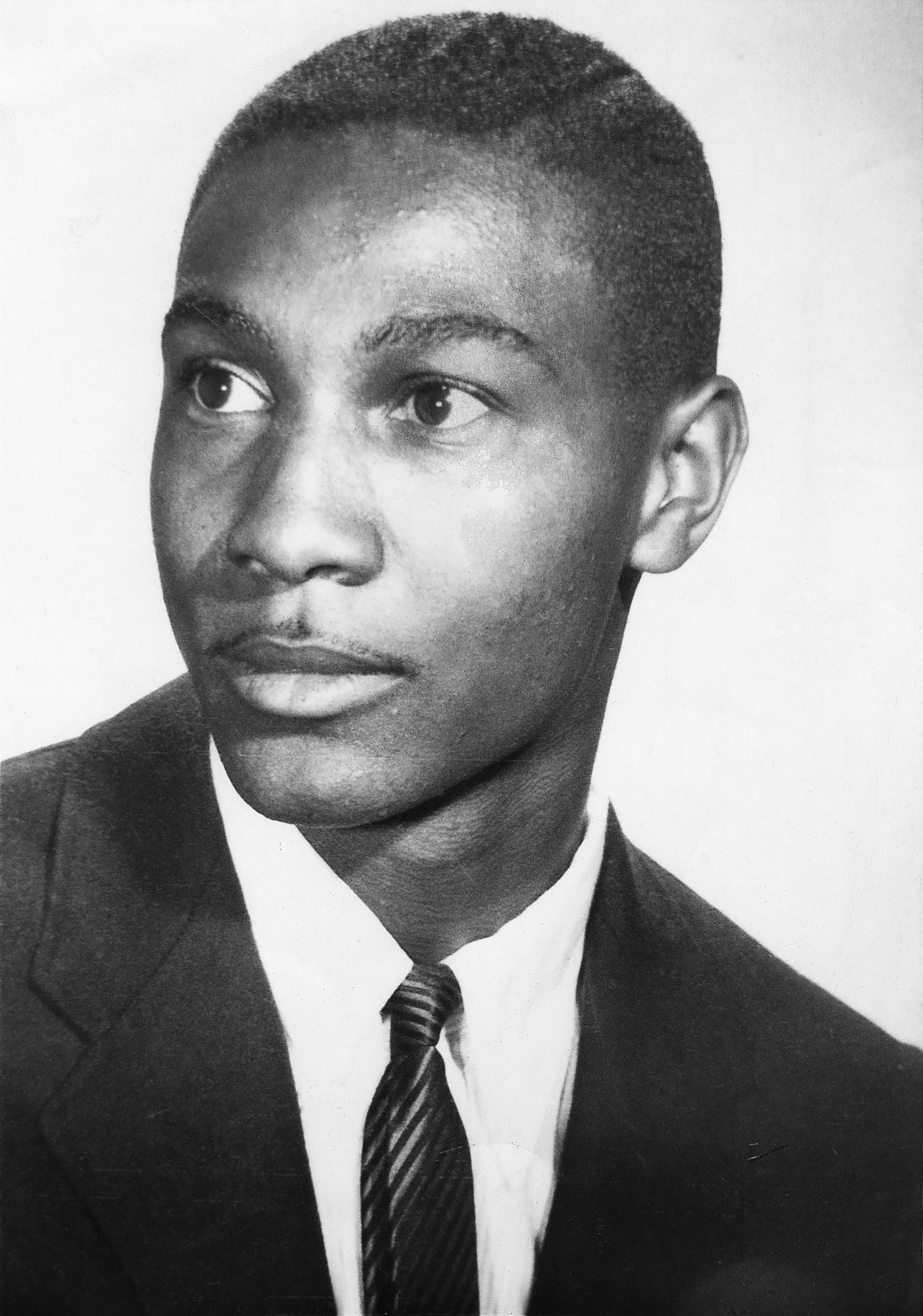

Despite living in a “rough segregated area filled with crime and poverty,” Whiten recalls that the local Black community was composed of business owners as well as professionals, including doctors and dentists, several of whom took an interest in his development. A bright student and an attentive listener, Tim attended Carver Elementary School, Fellrath Junior High School, and Inkster High School (which he graduated from in 1959). The pharmacist William Eldon, who hired Tim as a teenager, mentored him in mathematics. When Tim was in graduate school, Eldon also gave him a car, facilitating his travel back to university and the transport of art materials and supplies.

Tom Whiten’s younger sister Harriett Beasley, known to Tim as Aunt Bea, was viewed as the “matron of the village” and highly respected, as Tim recalls. She owned and operated a restaurant with a handyman named Mr. Charleston on Harrison Avenue, a short walk from the Whiten family home, which served authentic southern cuisine: fried chicken, barbecued ribs, collard greens, cornbread, stewed cabbage, eggs and hominy grits, sweet potato pie, and Hoppin’ John, a dish made from black-eyed peas and rice. As a preschooler, Tim spent his days playing at the restaurant while his aunt prepared meals and waited on customers. A healer, Aunt Bea tended to her nephew’s minor ailments and injuries with natural remedies.

Mr. Charleston, who worked for Aunt Bea, was an accomplished storyteller and a talented folk artist. His ability to turn common materials into unique creations charmed and inspired young Tim. For example, he made radio and TV consoles from tree branches spray-painted gold, silver, and black. Whiten’s artistic practice of transforming everyday objects and materials into provocative cultural objects grew in part out of these early experiences. His attenuated unicycle Clycieun, 1991, is a prime example.

In later years, Tim listened to live and recorded music at Aunt Bea’s home. She believed that music of any kind, especially Black Gospel music, could “open up the soul.” She invited local musicians to jam in her garage on weekends, including Tim’s elder brother Jim, who became a classically trained jazz musician. However, Tim’s early exposure to other cultural experiences was extremely limited: “Academically, culturally, and economically, the world outside my experience was unknown.”

An Education in Art

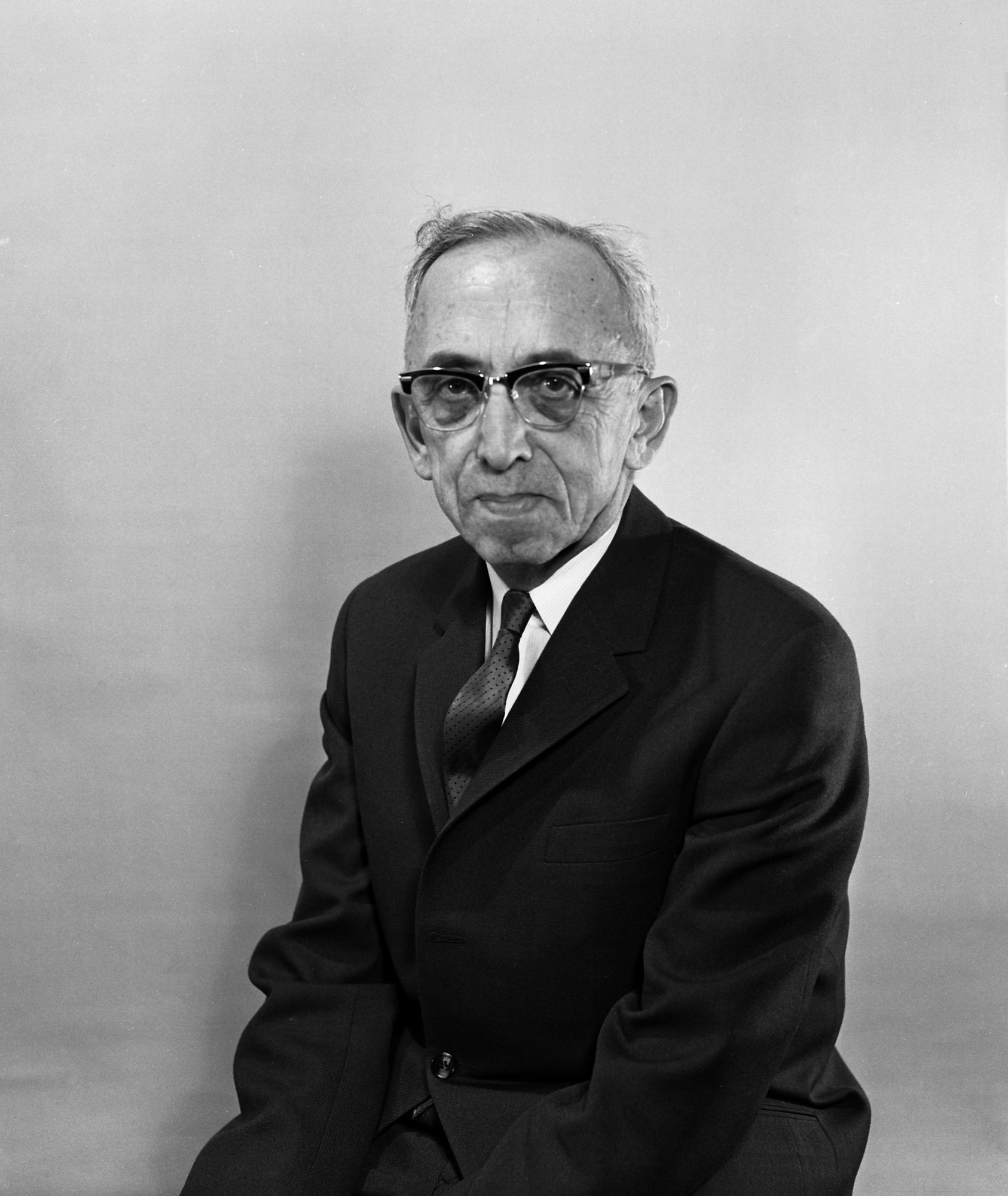

Whiten’s first engagement with art happened after graduating high school. Supported by his parents, he attended Central Michigan University (CMU) in Mount Pleasant, an affordable state university with high standards. There, the teachings of his professor, the influential philosopher Oscar Oppenheimer, inspired his lifelong interest in psychology and phenomenology. Considered by the artist to be his “intellectual father,” Oppenheimer, who was a Quaker, introduced Whiten to the world of ideas, of art, and of the spiritual. Whiten had intended to become a psychologist. As his academic adviser, Oppenheimer suggested he take courses in art. He reasoned that Whiten should explore the “conditions of becoming” found in expressions throughout the world to aid in the therapeutic process and in his development as a counsellor and educator. “At the time, I never thought about making art as a vocation,” Whiten comments.

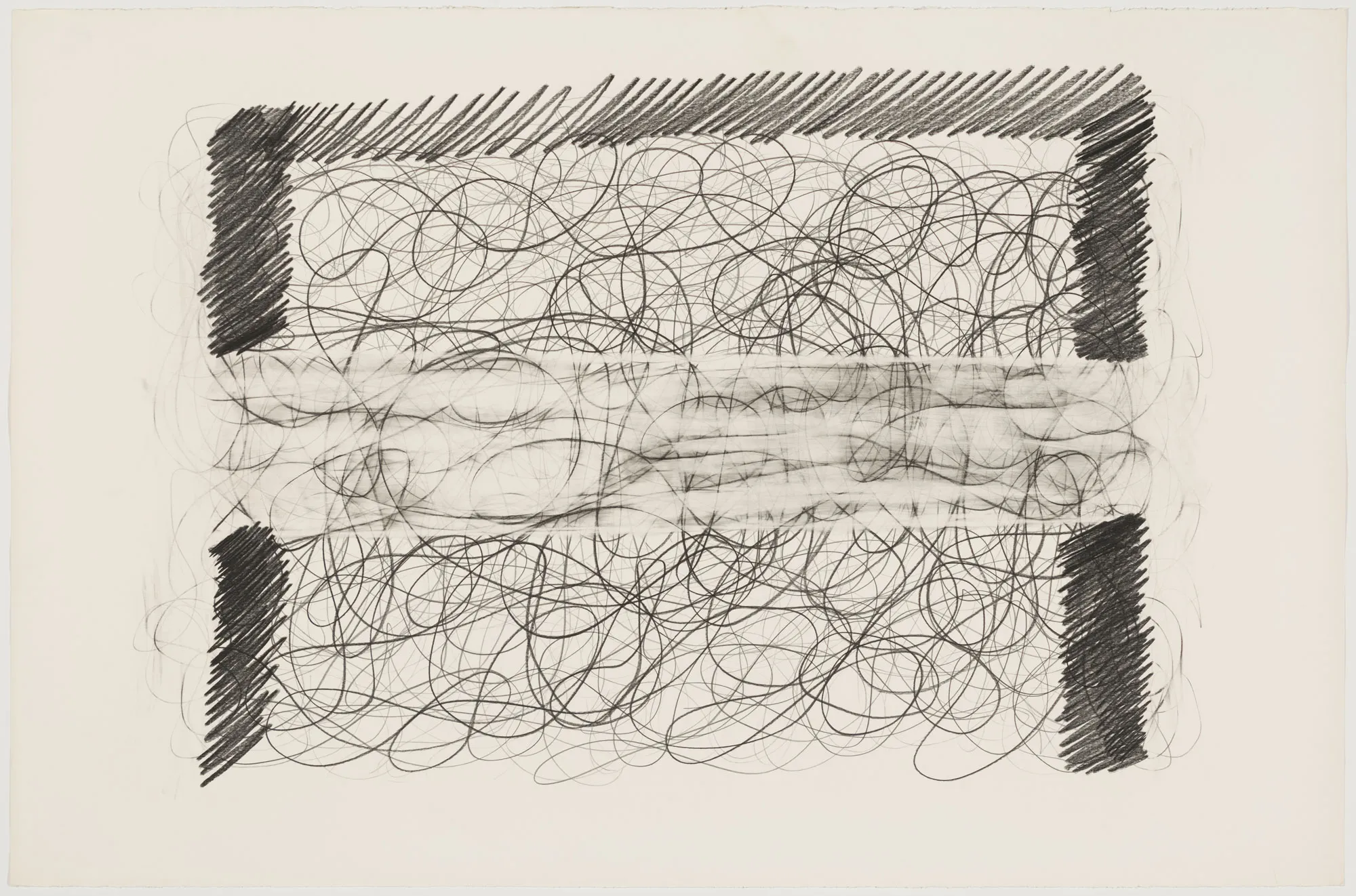

During his undergraduate studies, Whiten took studio courses in landscape painting and figurative sculpture working from the model. At the same time, he taught extracurricular studio art at CMU and later taught students at Maude Kerns Art Center, a private art school in Eugene, Oregon. Under Professor Katherine Ux, he enrolled in a fundamentals course in drawing. For Ux, a graduate of the progressive Cranbrook Academy of Art, drawing was more than a preparatory tool in the production of a work of art: it was a tool of the imagination “not limited to the demonstration of physical reality but approached as a possibility beyond representation.” Quoting Paul Klee (1879–1940), she would say, “A drawing is simply a line going for a walk.” Ux opened the door to drawing as a tool to understand human consciousness, a gesture to be shared, to be experienced by others. Whiten’s later drawing practice demonstrates these influences—evident in his 1981 series Magic Gestures: Lites and Incantations, where seemingly random mark-making captures the rhythmic gestures of the body.

With Ux’s encouragement, Whiten took studio courses under the professors and artists Robert Burkhart, Ray Nitschke, George Manupelli (1931–2014), and John Zeilman. Tours of art museums in New York City during an intensive four-week travel course led by Manupelli in 1963 also opened his eyes to contemporary visual art. These experiences were augmented by access to Arts Magazine, Artforum, Art in America, Art International, and other periodicals, lent to him by the artist Virginia Seitz, who oversaw the extracurricular arts program at CMU.

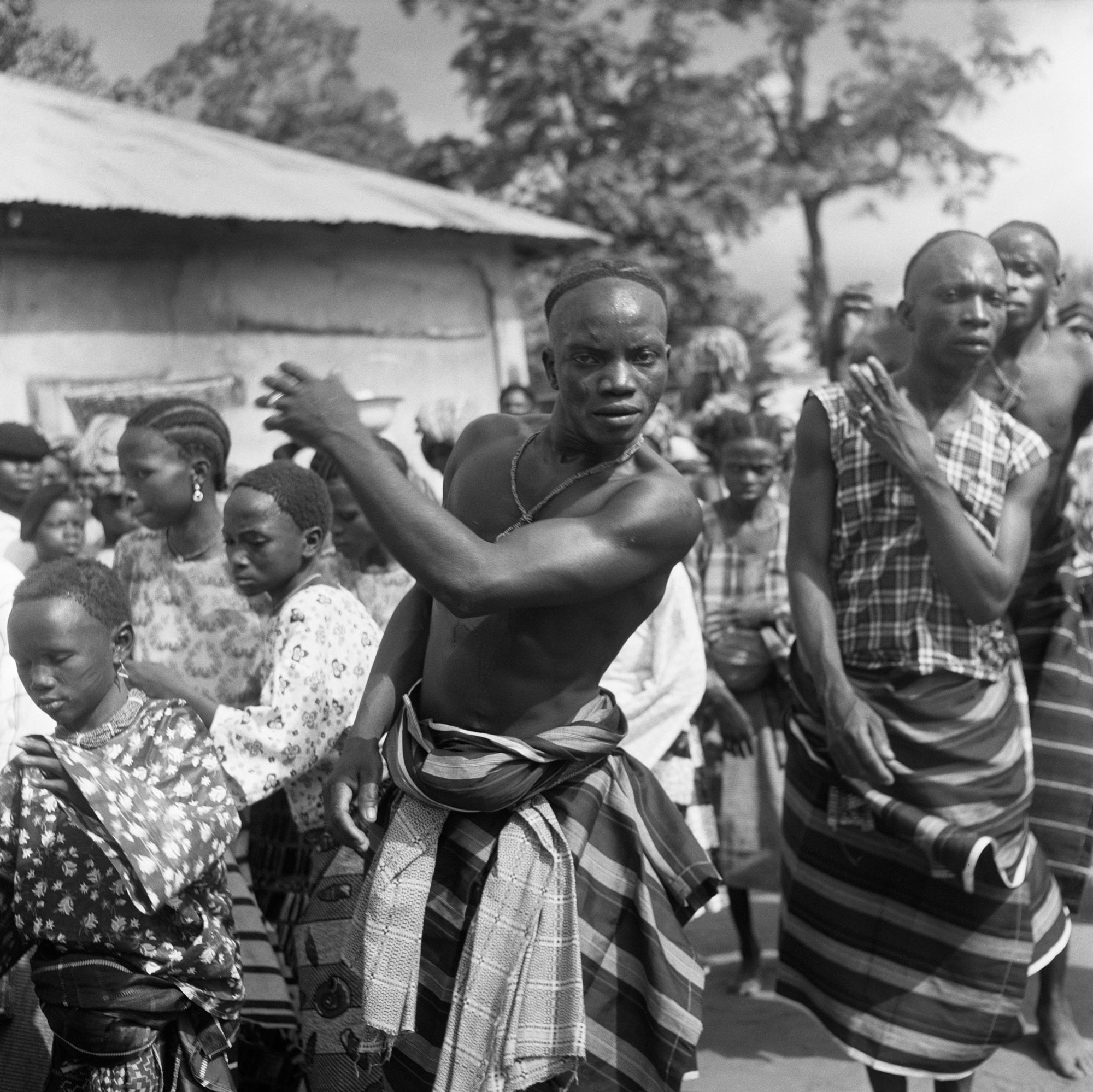

Furthermore, Seitz exposed Whiten to African, Inuit, and Indigenous material cultures, not part of the Western art historical canon at that time. For Whiten, whose ancestral lineage can be traced to the Kingdom of Kongo, the cultural objects and images from Central Africa particularly sparked his interest in understanding his own heritage and the attendant spiritual values these objects embodied.

Uninspired by the representational landscape and figurative traditions that surrounded his academic life, Whiten turned to the work of Russian Constructivists such as Naum Gabo (1890–1977), Vladimir Tatlin (1885–1953), and Alexander Rodchenko (1891–1956), underscored by the tenets of structuralism and semiotics; the lyrical abstract expressionistic paintings of Arshile Gorky (1904–1948); and the European artists of the avant-garde such as Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944), and Piet Mondrian (1872–1944), whose explorations were predicated on the nature of the spiritual conveyed through cultural expression.

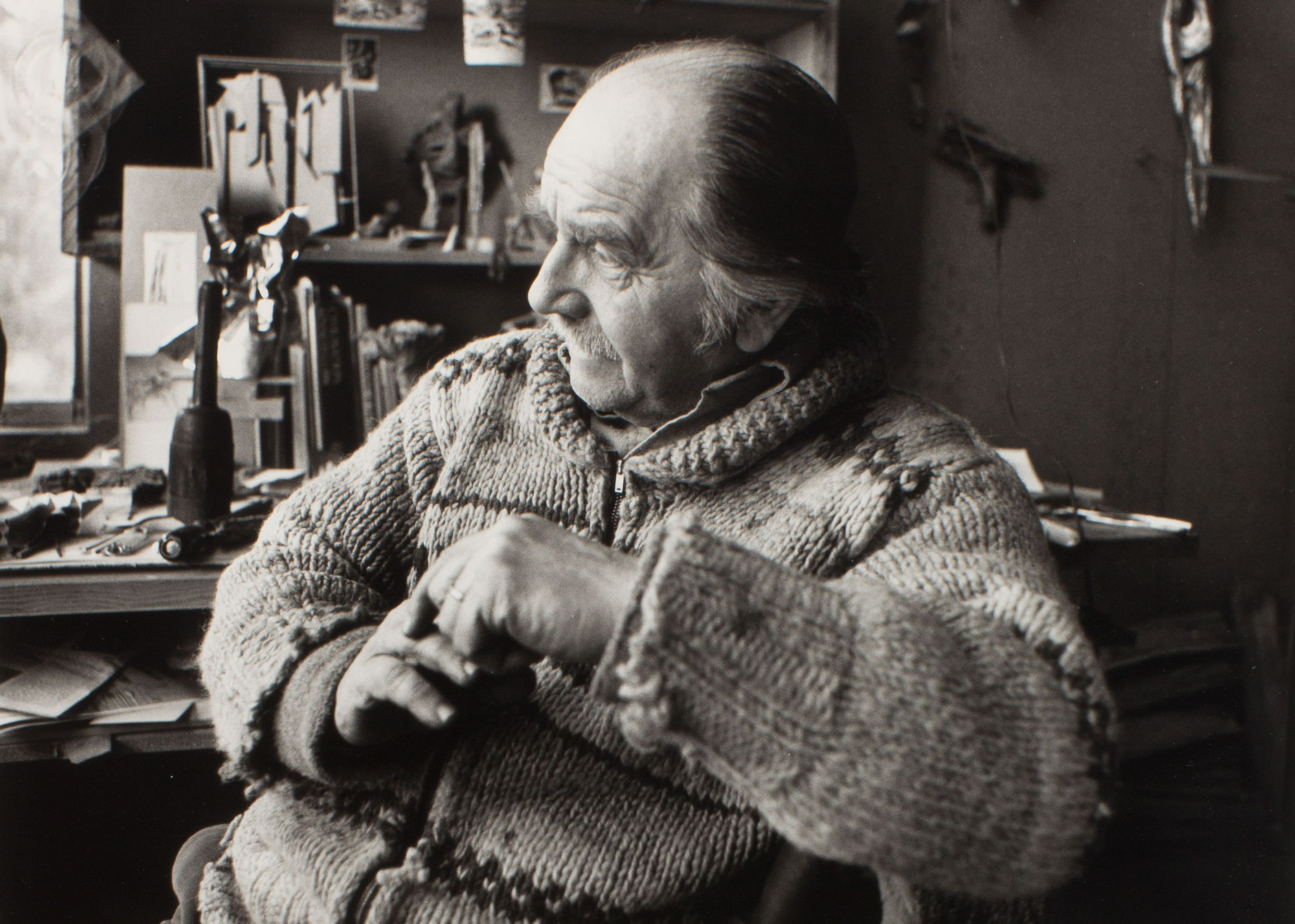

In early January 1964, Whiten earned a Bachelor of Science degree in Applied Arts and Sciences, with combined majors in psychology, philosophy, visual art, and military science. In the spring of that year, he started graduate studies at the School of Architecture and Allied Arts at the University of Oregon (UO) in Eugene, studying fine art under Czech Constructivist artist Jan Zach (1914–1986), whom he considers his “artistic father.” Zach, chair of the sculpture department, had studied art and design in Europe and was versed in the artistic movements abroad, which Whiten was drawn to.

During this period, Whiten pursued his interests in phenomenology under Professor Bertram Jessup and met fellow graduate student Anne Trueblood Brodzky (1932–2018), who became a lifelong friend and colleague. Through the study of structuralism and semiotics, he also explored the nature of language as a mode of understanding art. Augmenting his experience as an educator, Whiten taught sculpture fundamentals and second-year sculpture at the UO.

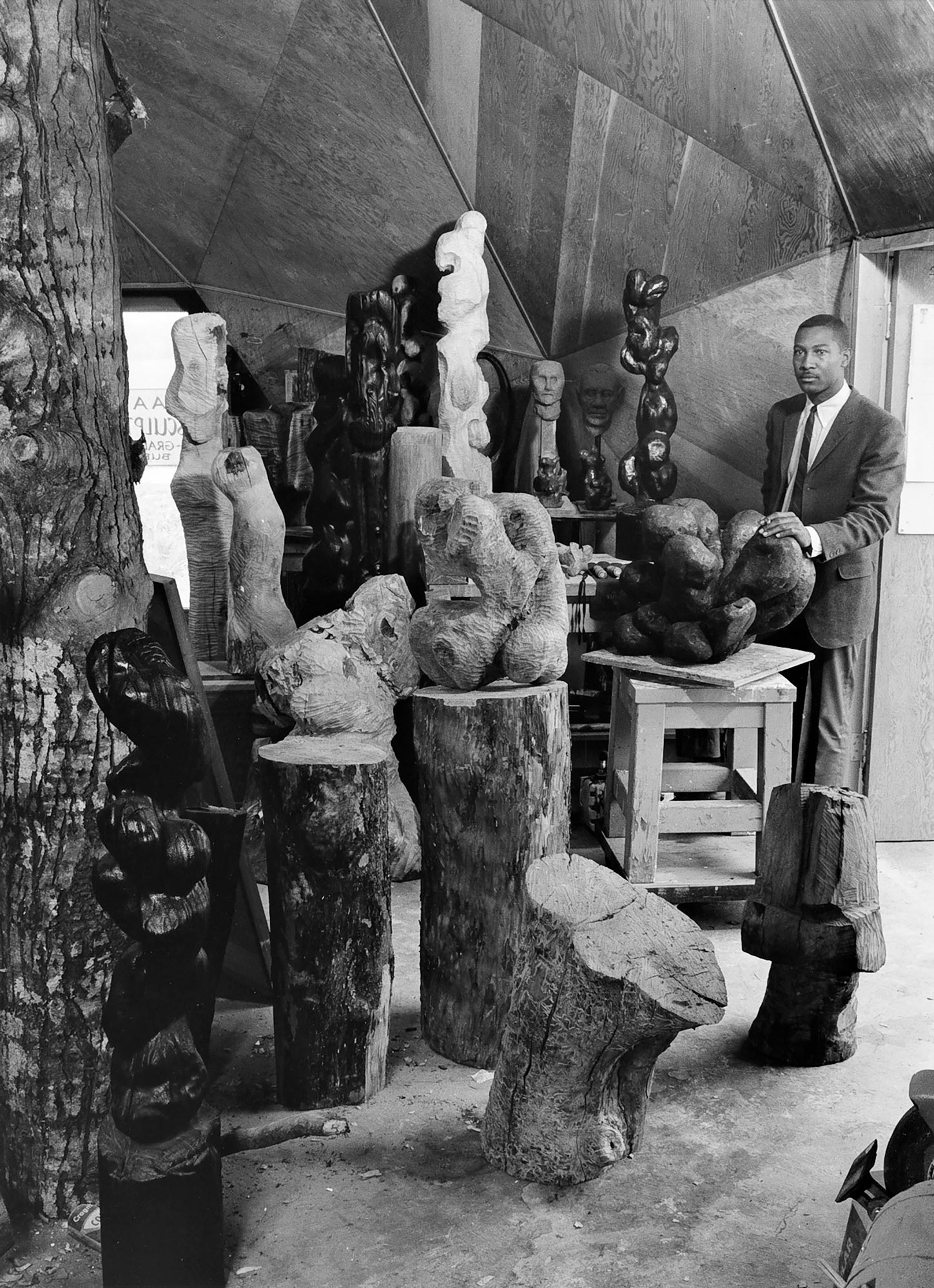

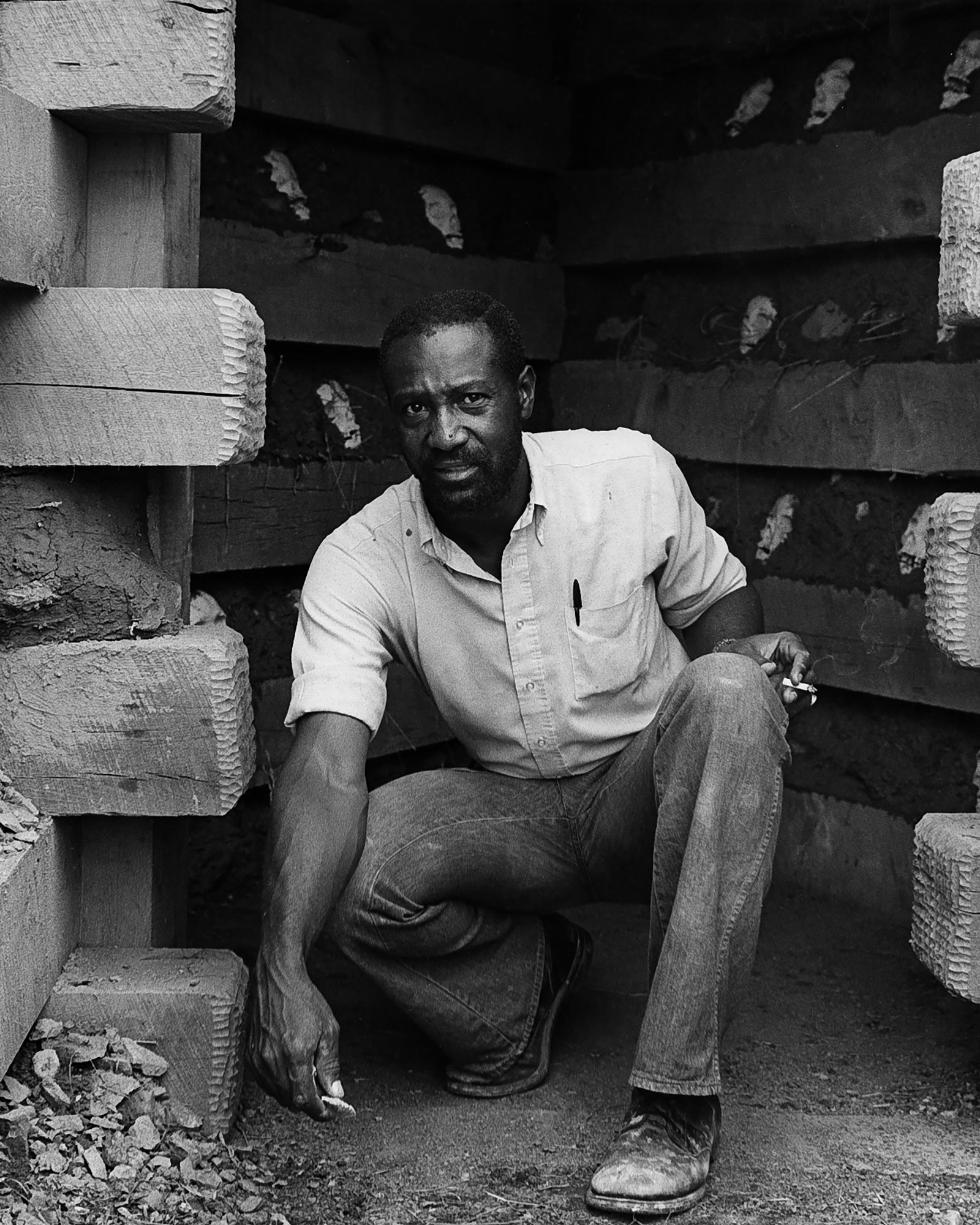

While in graduate school, Whiten’s studio practice focused on carving directly in wood and stone, producing abstract sculptures inspired by geometric and organic forms, with contours suggestive of works by Jean Arp (1886–1966) and Henry Moore (1898–1986). Drawn to the materiality and formal language of European modernist artists, Whiten was especially influenced by the carved sculptures of Constantin Brâncuși (1876–1957) as well as the “readymades” of Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968). His research into the material culture and ritual processes of African, Indigenous, and Oceanic peoples further informed his artistic development, as can be seen in his later ritual performances, such as Metamorphosis, 1978–89.

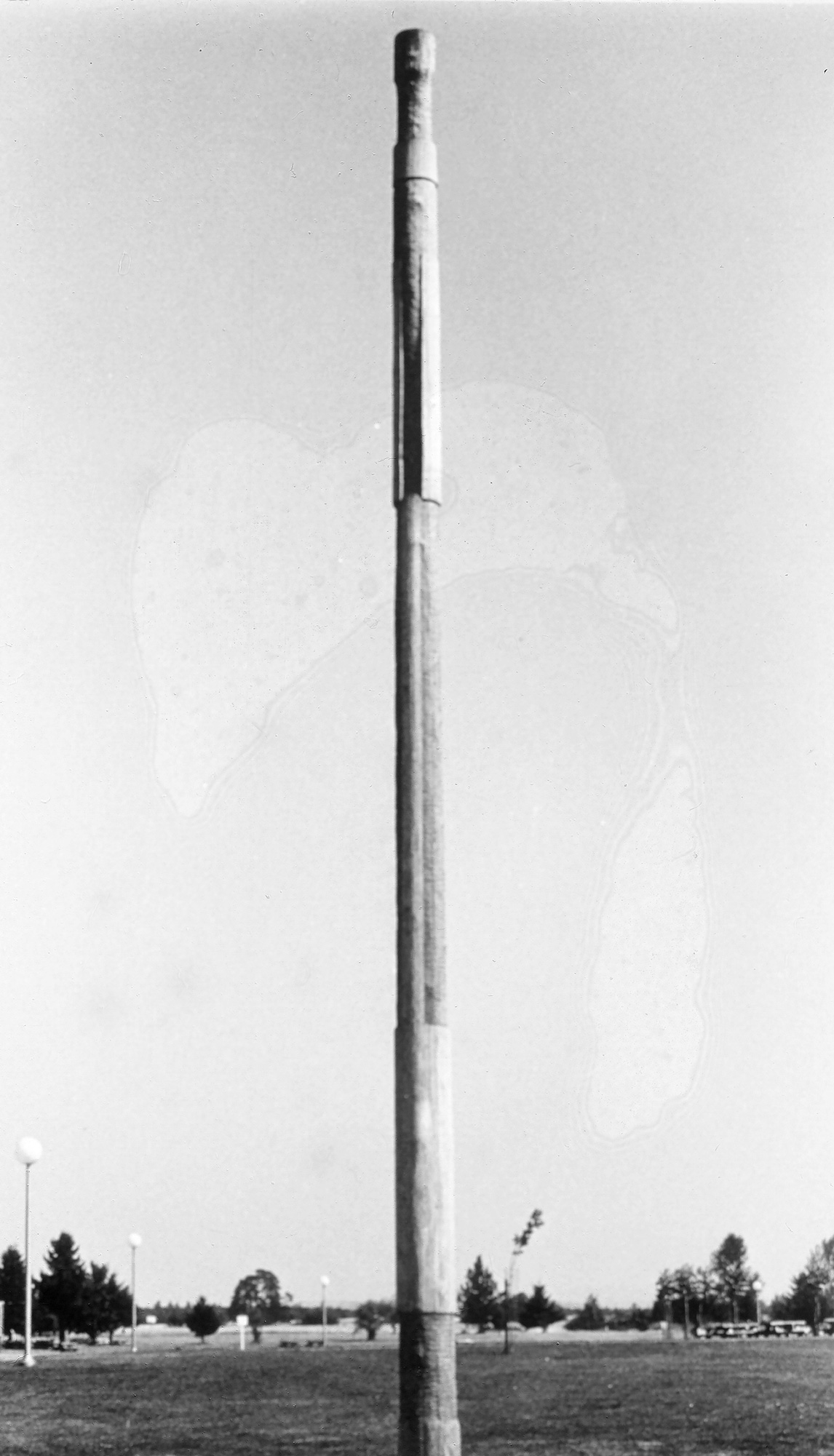

In June of 1966, Whiten received a Master of Fine Arts degree with a specialization in sculpture, having completed additional course work in phenomenology, art history, and printmaking (etching/lithography). Upon graduation, he was encouraged by his graduate adviser Zach to create a public artwork. Erected in Jasper State Recreation Site near Eugene, Cosmological I was accomplished with donated materials and installation support, but without a fee. Modelled after Brâncuși’s Endless Column, version 1, 1918, a physical manifestation of spiritual ascension, Whiten’s monumental totem-like sculpture—a 45-foot-high cedar pole—acted as a vertical landmark in a context otherwise devoid of directional signs, pointing to that which is beyond what we see and know.

Military Service and Immigration to Canada

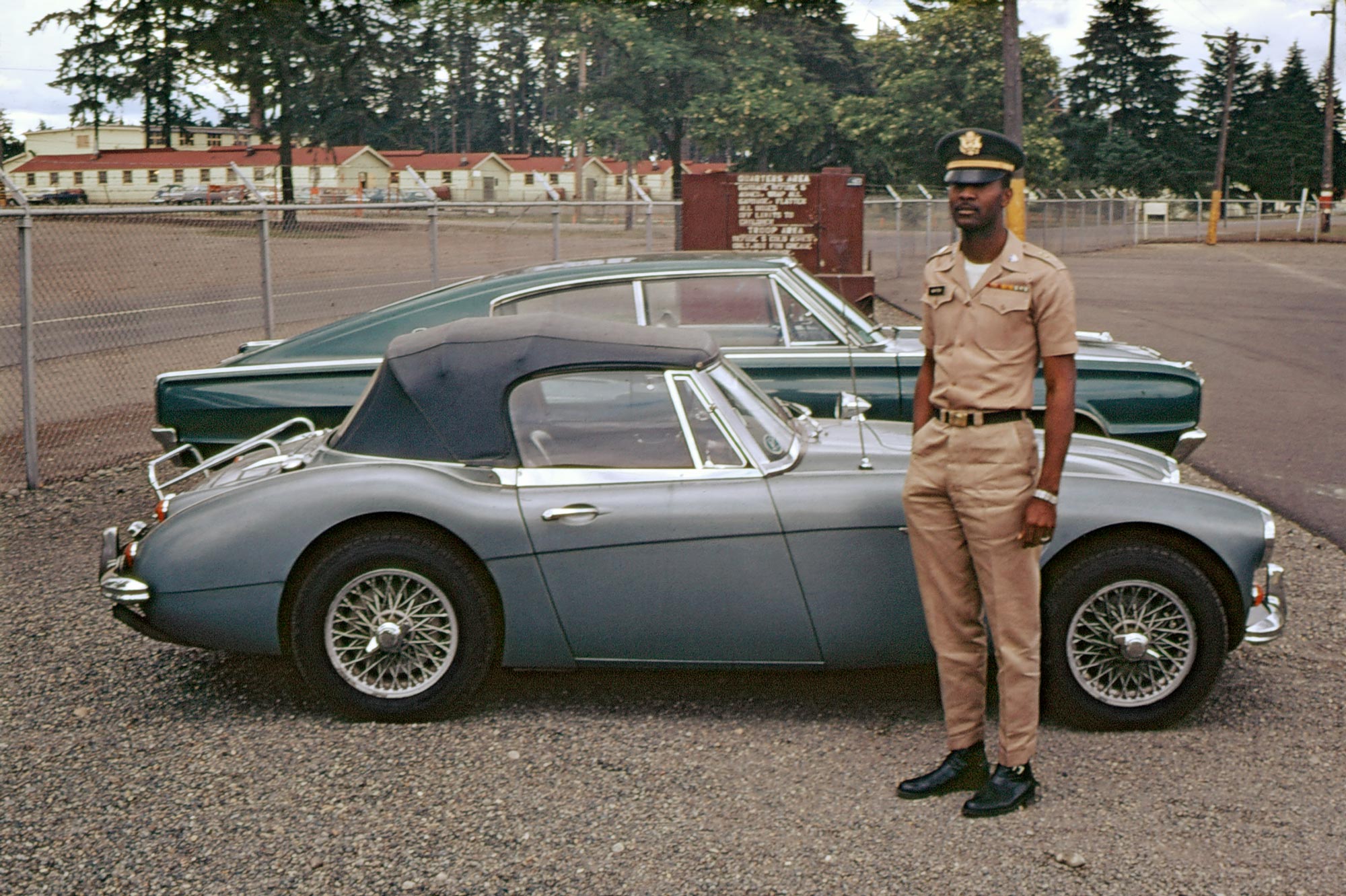

That same summer, Whiten entered active military duty. He had received a commission in the U.S. Army, Rank/2nd Lieutenant, in 1964 but deferred active duty until after graduate studies. In July 1966, he began specialized training as an Adjutant General Officer in Indianapolis, Indiana. In the fall of 1966, he was assigned to the 381st Replacement Company, Fayetteville, North Carolina, home of the 82nd Airborne, for staging in preparation for unit shipment to South Vietnam.

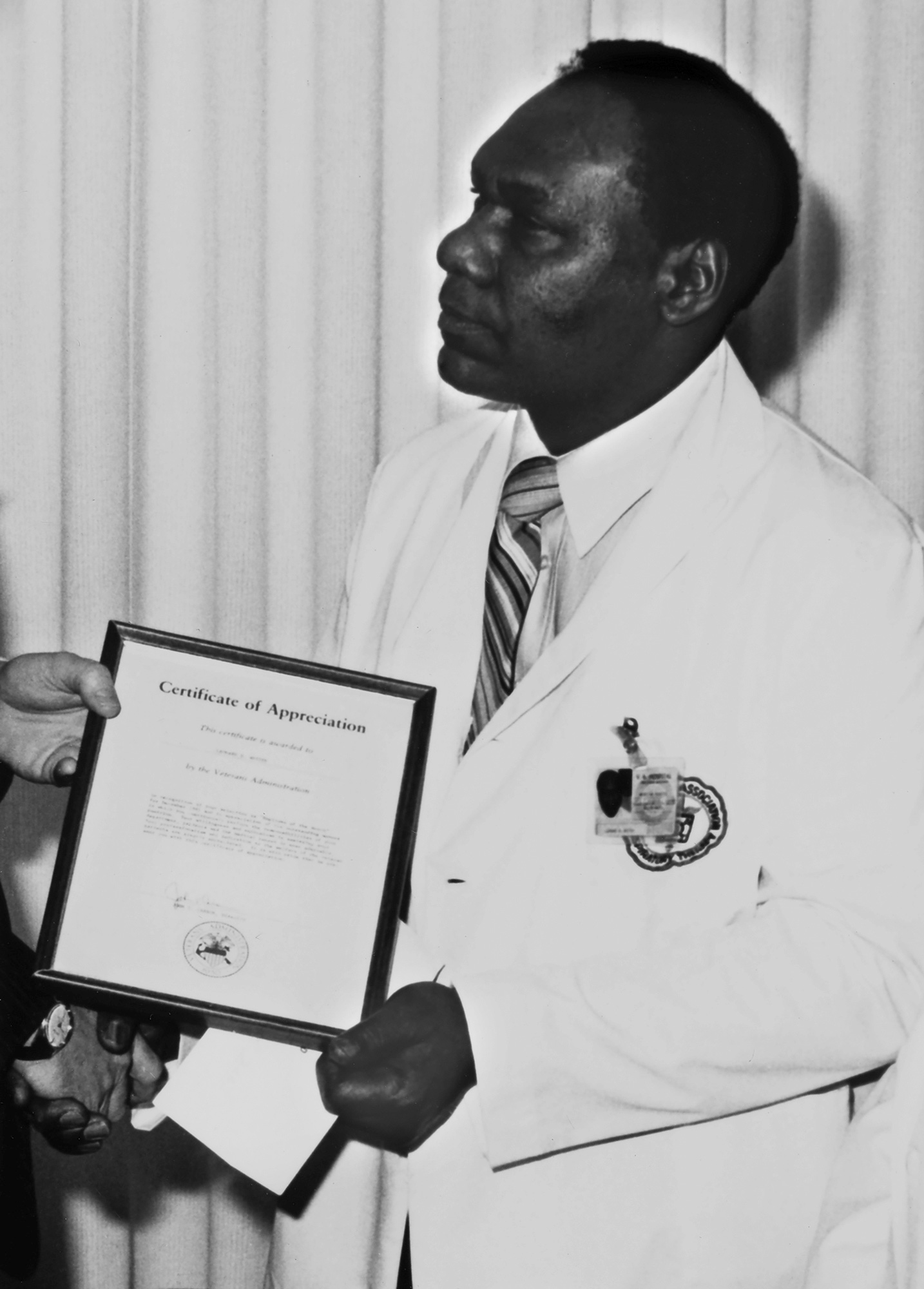

Whiten began his foreign tour of duty in January of 1967 in Long Binh Post, South Vietnam, and returned to the United States in December of 1967, where he was assigned to the U.S. Army processing station in Olympia, Washington, at the 6th Army Armed Forces Entrance and Examination Services. He was released from active duty in June of 1968, after achieving the rank of captain with letters of commendation, and honourably discharged in 1970.

Whiten’s faith in the United States was deeply shaken by his experiences during the Vietnam War (1955–75), the bigotry he encountered while in the military, and the appalling treatment of U.S. veterans upon their return. The assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy in 1968, and the violence, racial segregation, and riots at the height of the civil rights movement, further exacerbated his profound disillusionment. He realized that living in the U.S. could quickly become intolerable.

Anne Trueblood Brodzky had immigrated to Canada in 1965 and two years later became the editor of artscanada, the country’s leading arts magazine. She encouraged Whiten to apply for a teaching position in the Humanities Division of the Faculty of Arts at York University (York) in Toronto, a city where racial discrimination and tensions were less prominent than in the U.S. Whiten was interviewed by John (Jack) Saywell, Dean of the Faculty of Arts; Henry Best, Registrar; and artist Ronald Bloore (1925–2009), Visual Arts Representative and Professor in the Division of Humanities. An accomplished candidate in many respects—he was an experienced educator with a strong background in visual art as well as the humanities—Whiten was offered the position, which he immediately accepted. He immigrated to Canada in August of 1968 with his fiancée, Colleen Bush, whom he had met during graduate studies and would marry in Toronto that September.

In 1969, Whiten became a founding member of the Faculty of Fine Arts at York and the newly formed Department of Visual Arts, with a cross appointment to the Faculty of Arts. His first course was entitled “Imagination and Perception,” with professors Michael Creal and Bloore as co-lecturers. As the tutorial leader, Whiten was responsible for generating dialogue around the lecture material, reviewing written assignments, and grading papers and exams. Additionally, he was made a fellow of Vanier College and was given an office and the use of two workrooms there as Director of Extracurricular Activities in Art, as well as a personal studio in Stong House with Bloore, which was also used as an extracurricular studio space by students.

Tim Whiten, Untitled, 1972, leather and stone, 28 x 29.2 x 25.4 x 28 cm, courtesy of the artist and Olga Korper Gallery, Toronto.

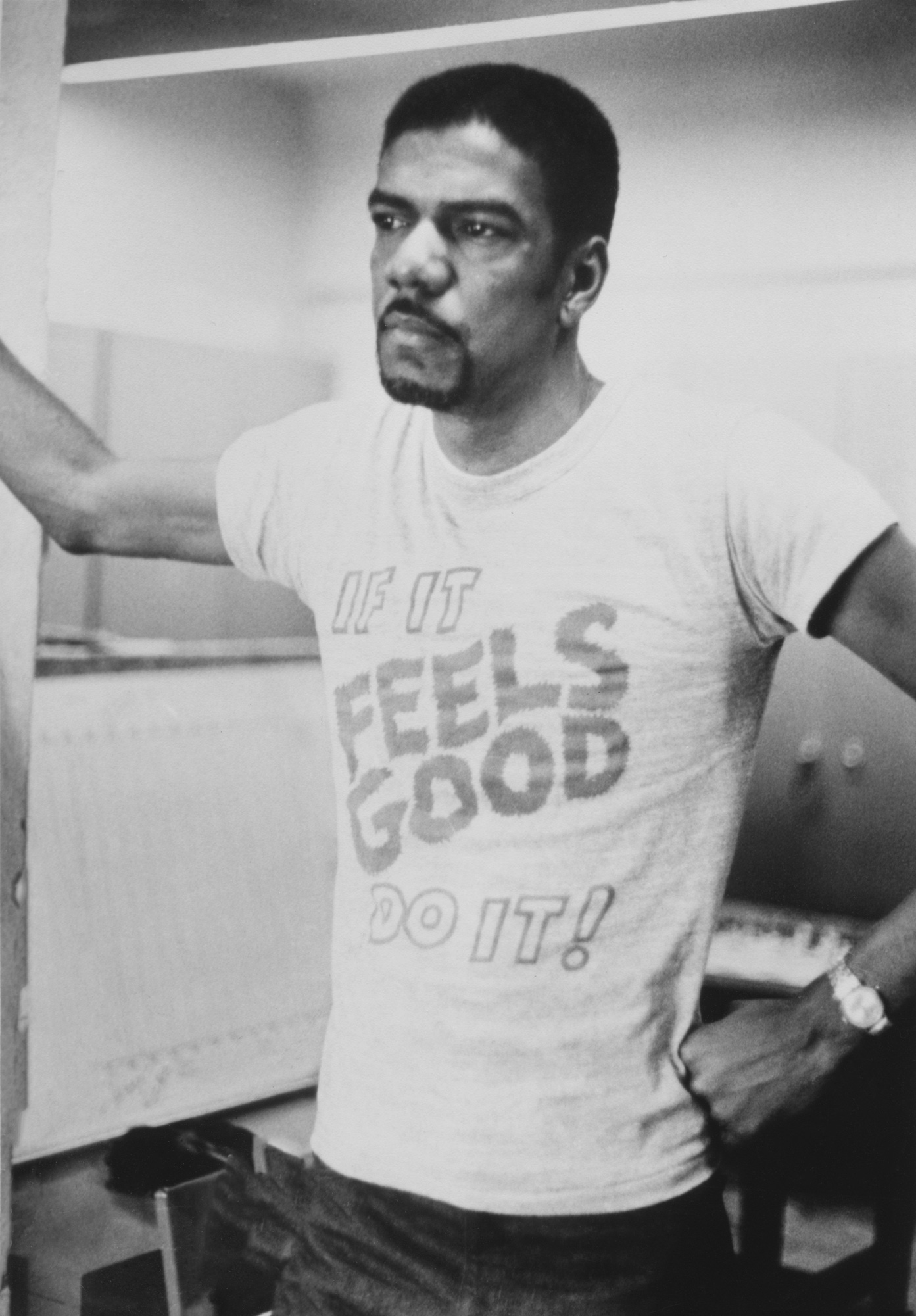

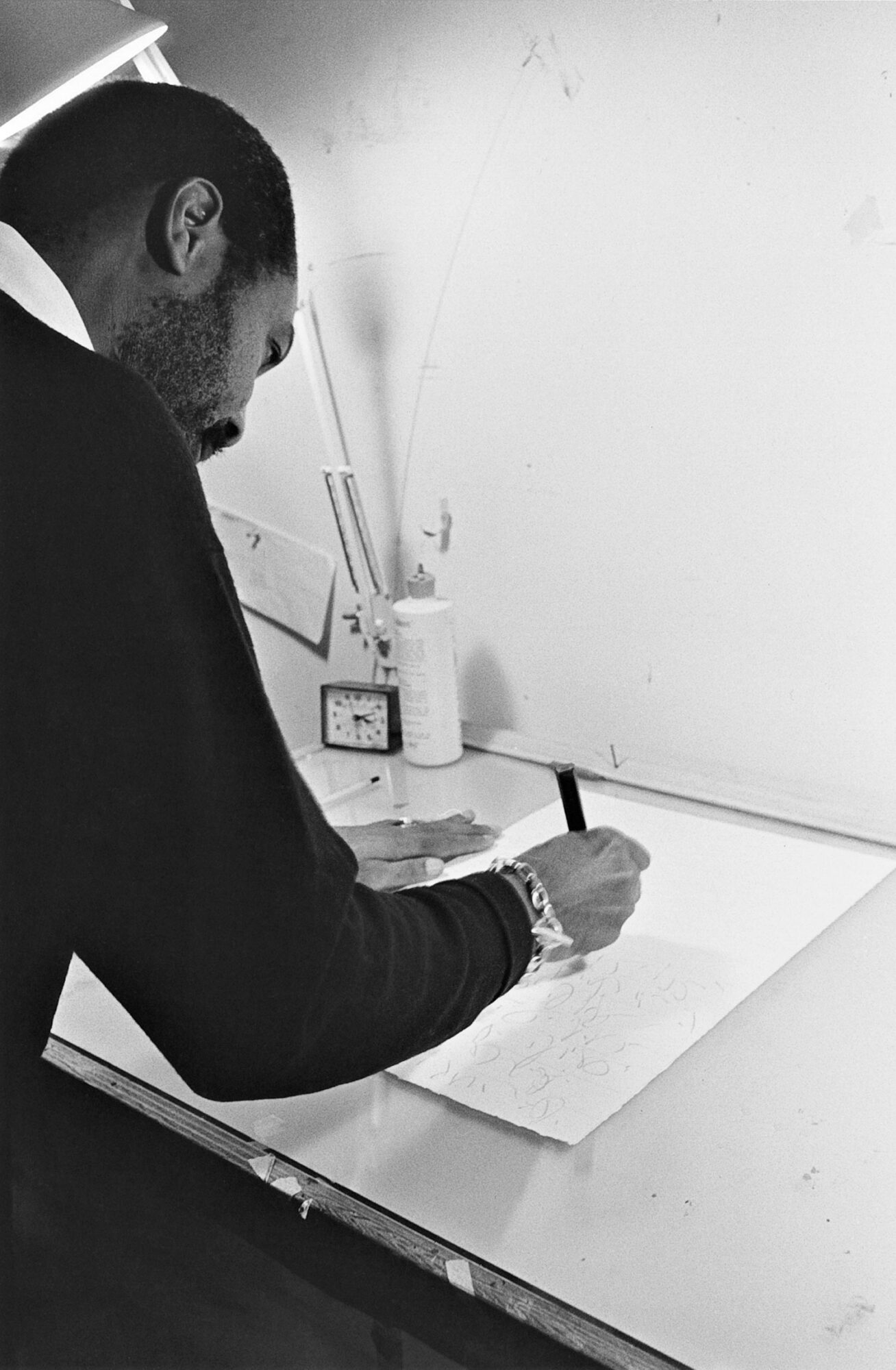

Tim Whiten in his studio, Toronto, 1974, photograph by Eberhard Otto.

With colleague and artist Ted Bieler (b.1938)—a practising Buddhist who shared Whiten’s interest in the spiritual and who possessed advanced technical skills—Whiten created the sculpture program at York. Like Katherine Ux, who was so influential to Whiten at Central Michigan University, Bieler had studied at the Cranbrook Academy of Art; he was also a former student of Jan Zach, who had taught him drawing as a teenager. Other notable colleagues at York included artists George Manupelli and Vera Frenkel (b.1938), and African scholar Zdenka Volavka, who understood the vital connection between Whiten’s studio practice and African sculpture.

Whiten taught at York for close to forty years, mentoring generations of Canadian artists. Starting as a sessional instructor, he achieved the rank of Professor in 1974 and Full Professor in 1990. During his tenure, he was Director of the Master of Fine Arts Program in Visual Arts (1974–76); and Chair of the Department of Visual Arts (1984–86; 2000–2001). He also became an Oxford-certified ESL instructor in 1993 to better serve the university’s increasingly diverse student population. Whiten received the Distinguished Leadership Award for Extraordinary Service to the Arts from the American Biographical Institute in 1989 and the Faculty of Fine Arts Dean’s Teaching Award in 2000. He retired from full-time teaching in 2007 and was appointed Professor Emeritus.

Innovations in Drawing

During his early years teaching at York University, Whiten developed a large body of works on paper, employing drawing as a tool to expand consciousness and to facilitate perception of a world beyond the physical. At that time in Canada, drawing was considered a preparatory practice, a stage in the production of a painting or sculpture—simply put, a means to an end rather than an end in itself. The American art world held more progressive views.

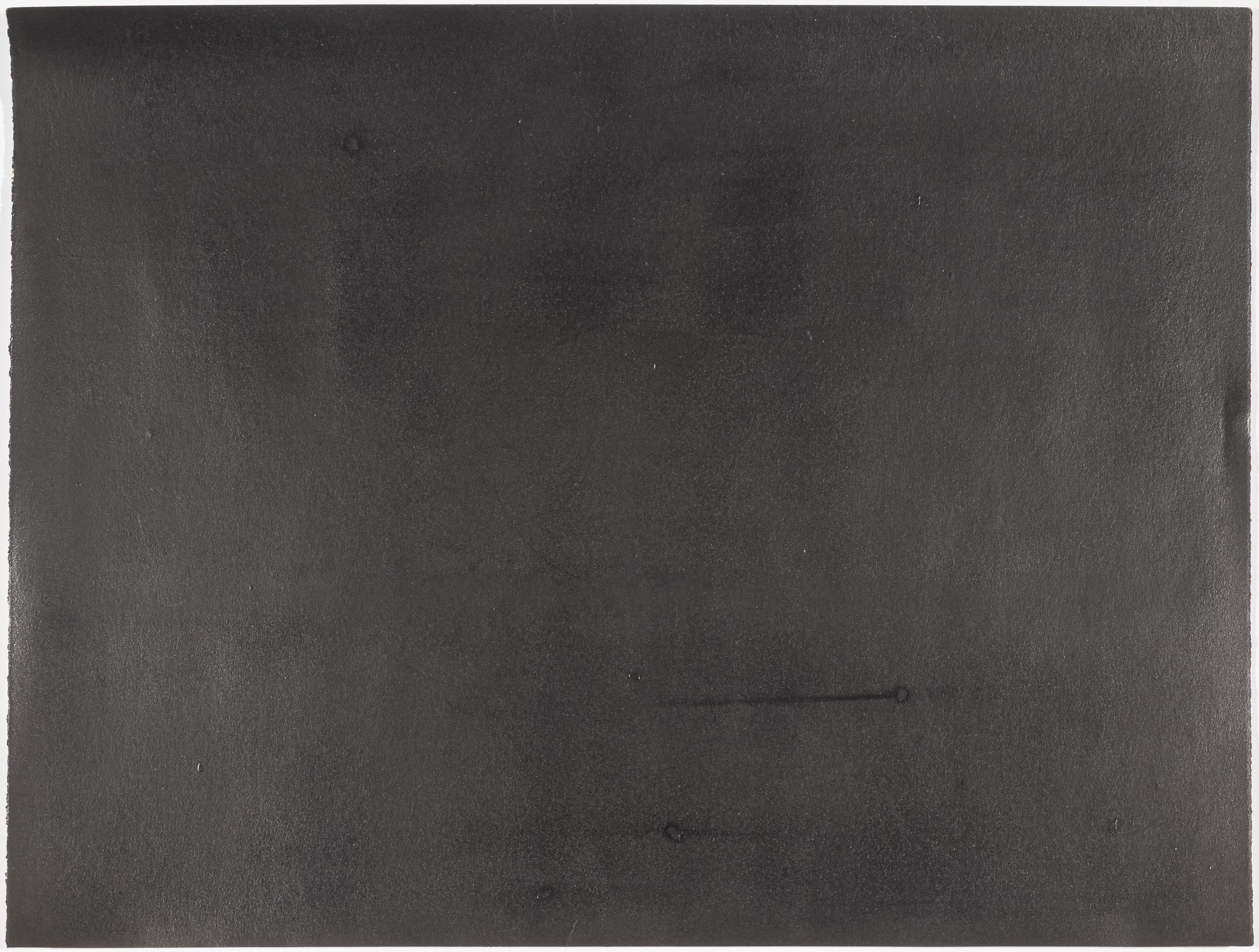

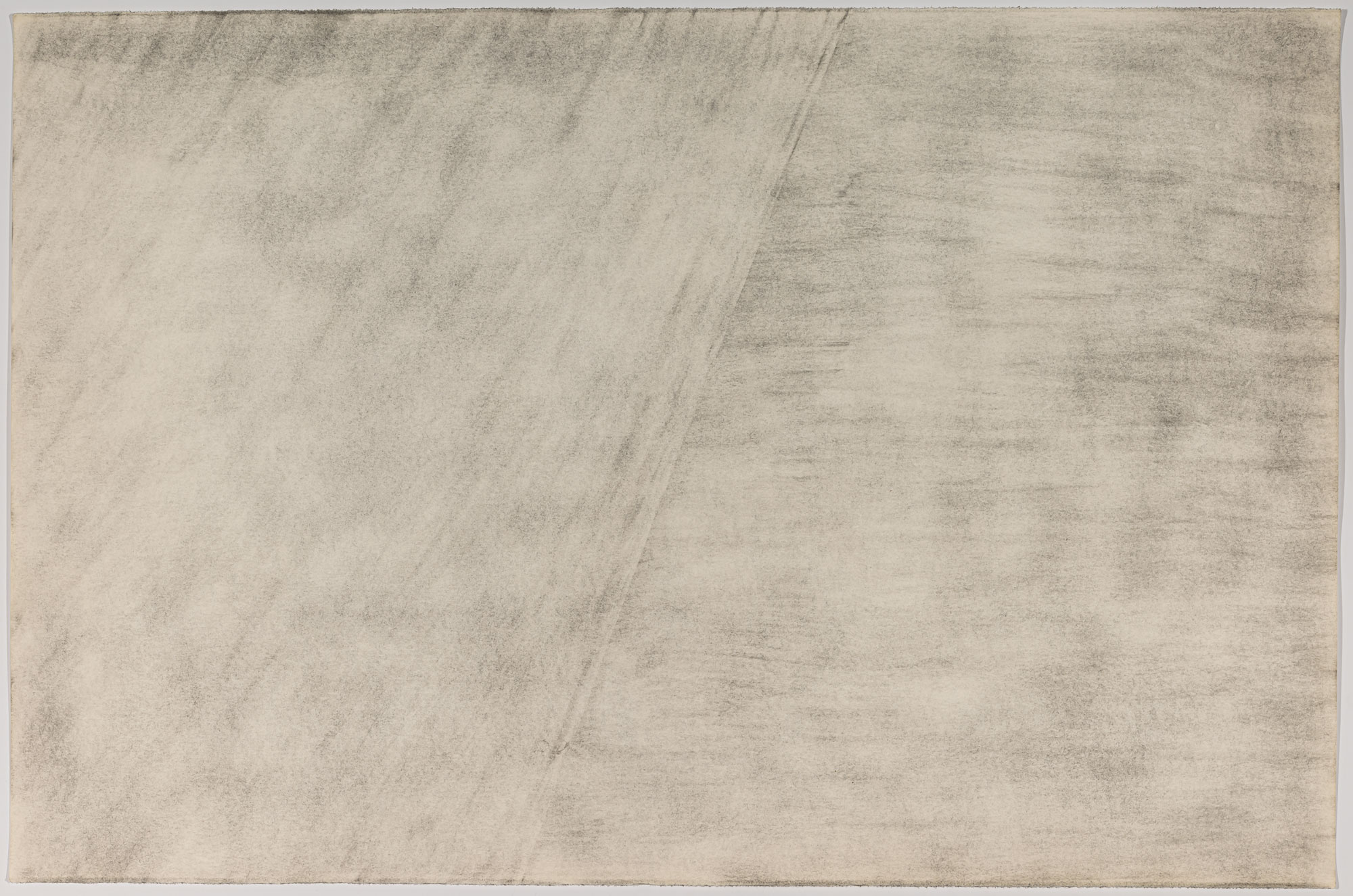

Whiten’s large, untitled graphite works on paper were included in a major drawing exhibition in 1970 at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston, presented alongside works by notable contemporary American artists such as Claes Oldenburg (1929–2022) and Eva Hesse (1936–1970), who, like Whiten, engaged gestural processes of repetition. As Whiten recalls, “My gestural graphite works arose from both a phenomenal and numinal awareness, while operating as a residue of consciousness.” This exhibition captured the attention of esteemed American art critic and curator John Noel Chandler in his 1970 artscanada article, “Drawing Reconsidered.”

Later that year, Whiten’s works on paper were featured in a two-person show in Toronto with painter Eric Cameron (b.1935) at the Nightingale Gallery. Whiten’s inaugural solo show, Meditation Metamorphosis and Psalm, which also comprised his graphite drawings, was held at Erindale College, University of Toronto, in 1971. For the artist, “these works on paper refer to the experiences of another world. They form the detritus of knowledge, the image impressions of human memory.”

Whiten’s first commercial representation was by the Jerrold Morris Gallery in Toronto, an affiliation launched in 1972 with an exhibition entitled Tim Whiten: Sculpture and Drawings, presented in collaboration with the Art Gallery of York University. In the 1972 catalogue foreword, curator Michael Greenwood describes Whiten’s work as possessing a “phenomenological rather than a symbolical or associational presence. We can exist in them, and with them, and through them, experiencing them like the fear of darkness or the sun’s rays upon our skin. We can hear their silent music and sense their stirring beneath the cloak of stillness.”

Using graphite on paper, Whiten’s heavily saturated surfaces perceptually change from black and white to colour, allowing one to see colour as the result of black and white: a direct phenomenal understanding of perceiving colour where there was none—an approach continued in his recent series Saying His Name…, 2017. In producing other drawings, such as Untitled, 1973, in the collection of the University of Toronto, Whiten erased the graphite surface, allowing the residue to create visual impressions. As the artist comments, “What is left is a memory, an eidetic experience, another aspect of consciousness, which is all things, including colour.”

Whiten’s works, especially his two-dimensional works, continued to be exhibited across the United States, presented in venues in New York City, Boston, Buffalo, Atlanta, and Washington. Significant group exhibitions featuring his work include those at the Alternative Museum, New York City (Post-Modernist Metaphors, 1981); the Visual Arts Museum, New York City (Sculptural Density, 1981); and the John Michael Kohler Arts Center, Sheboygan, Wisconsin (Remains to be Seen, 1983).

A Material Turn

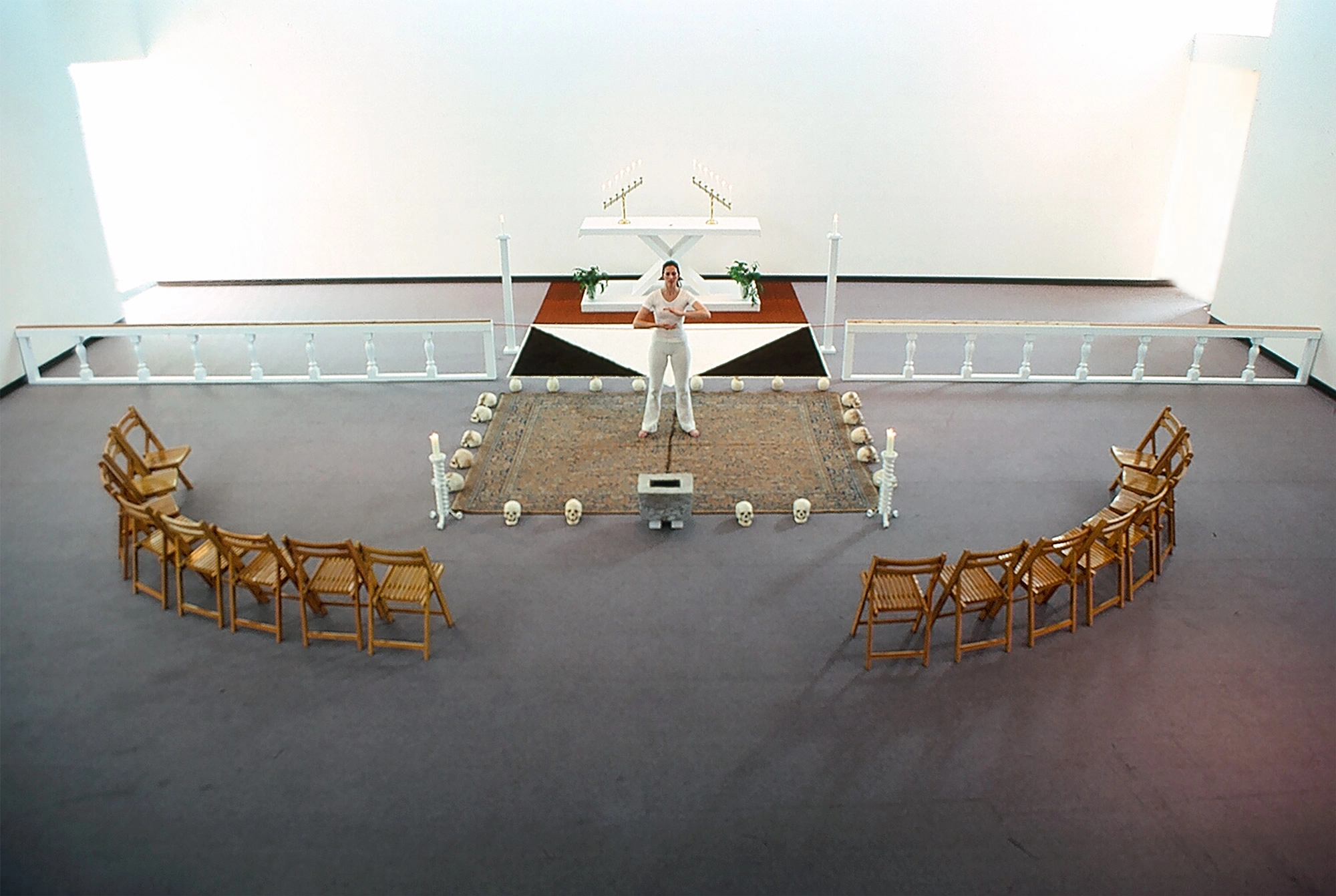

While maintaining his drawing practice, Whiten also began producing installations and ritual performances employing a variety of natural materials. In the 1970s and 1980s, his relationship with African cultural influences and materiality deepened. Human skulls, bones, branches, and animal hides became incorporated into his three-dimensional works. After Jerrold Morris retired in 1975, Whiten was represented by Paul Wong at Bau-Xi Gallery, with locations in Toronto as well as Vancouver. His first exhibition with Bau-Xi in 1976 included Ark, a work with fifty human skulls (purchased from a credited medical supplier) and presented in a large basket—a meditation on life, death, war, mortality, presence, and absence.

In 1980, Whiten presented Metamorphosis at Bau-Xi. In this ritual performance installation, the artist donned a bearskin pelt and then struggled to free himself without using his hands, a gesture of rebirth and transformation. Stage II of the Metamorphosis project, 1978–89, comprising the evidence of this ritual process, was later acquired by the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) and presented in Toronto: Tributes + Tributaries, 1971–1989, a major 2016 exhibition that featured more than one hundred artworks by sixty-five artists and collectives.

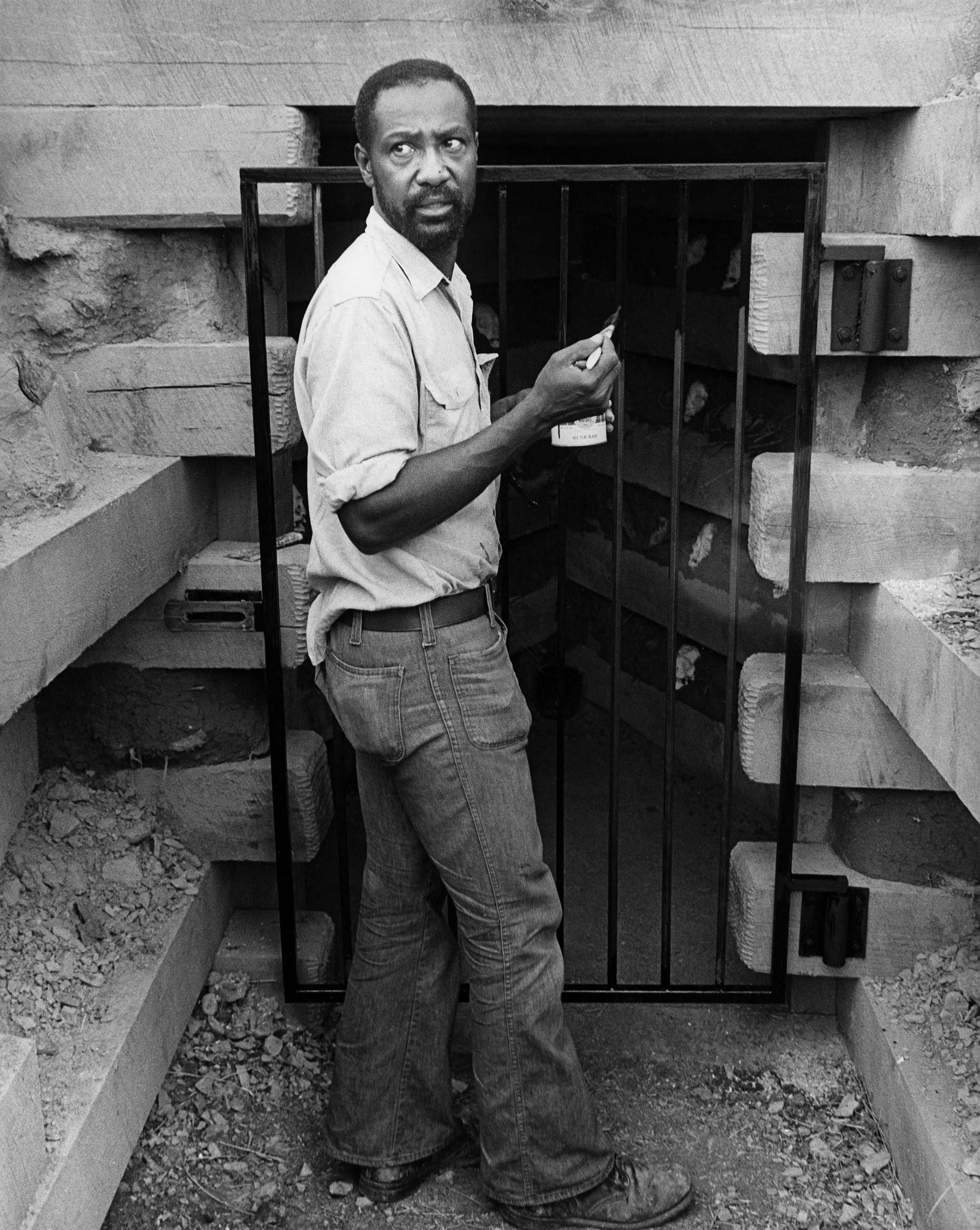

During this period, Whiten created several major outdoor projects. Using adobe, wood, human skulls, and other artifacts, he built structures to serve as sites for ritual processes while encouraging the experiential involvement of viewers. Morada, 1977, for which he received critical acclaim, was developed for Artpark in Lewiston, New York, and comprised a progressive series of stages or ritual stations, including an underground chamber with twenty-two human skulls embedded in its walls. As Whiten comments: “Each viewer will get his own meaning from the cave and the skulls but I’d like some, at least, to be reminded that there is a thread running from the past through the individual out into the timelessness of eternity, that life and death are really one continuum.” Garnering the attention of renowned American art critic Lucy Lippard (b.1937), a detailed description of this temporal project, including photographs, was featured in her seminal 1983 book, Overlay: Contemporary Art and the Art of Prehistory.

Whiten’s interest in performance as an art form was fostered during his years at the University of Oregon (UO). As a graduate student, he was introduced by Jan Zach to the innovative American composer John Cage (1912–1992), who invited him to participate in two events. The first was an evening of new music sponsored by the Department of Music at the UO (Encounter in Oregon: An Evening of New Music, University of Oregon, School of Architecture and Allied Arts, 1965). Whiten helped produce three-dimensional objects from plaster and wood for Cage’s performances. The second was Lecture on the Weather, 1975, written and directed by Cage and commissioned for the United States Bicentennial. It premiered at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery in Buffalo in 1976, with a subsequent presentation at the Music Gallery in Toronto in a program entitled Four Worlds. For Lecture on the Weather, Whiten contributed a vocal recitation of vowel sounds, exploring their vibratory range as corresponding to colour. Whiten not only performed in this work but, at Cage’s request, wrote part of the score.

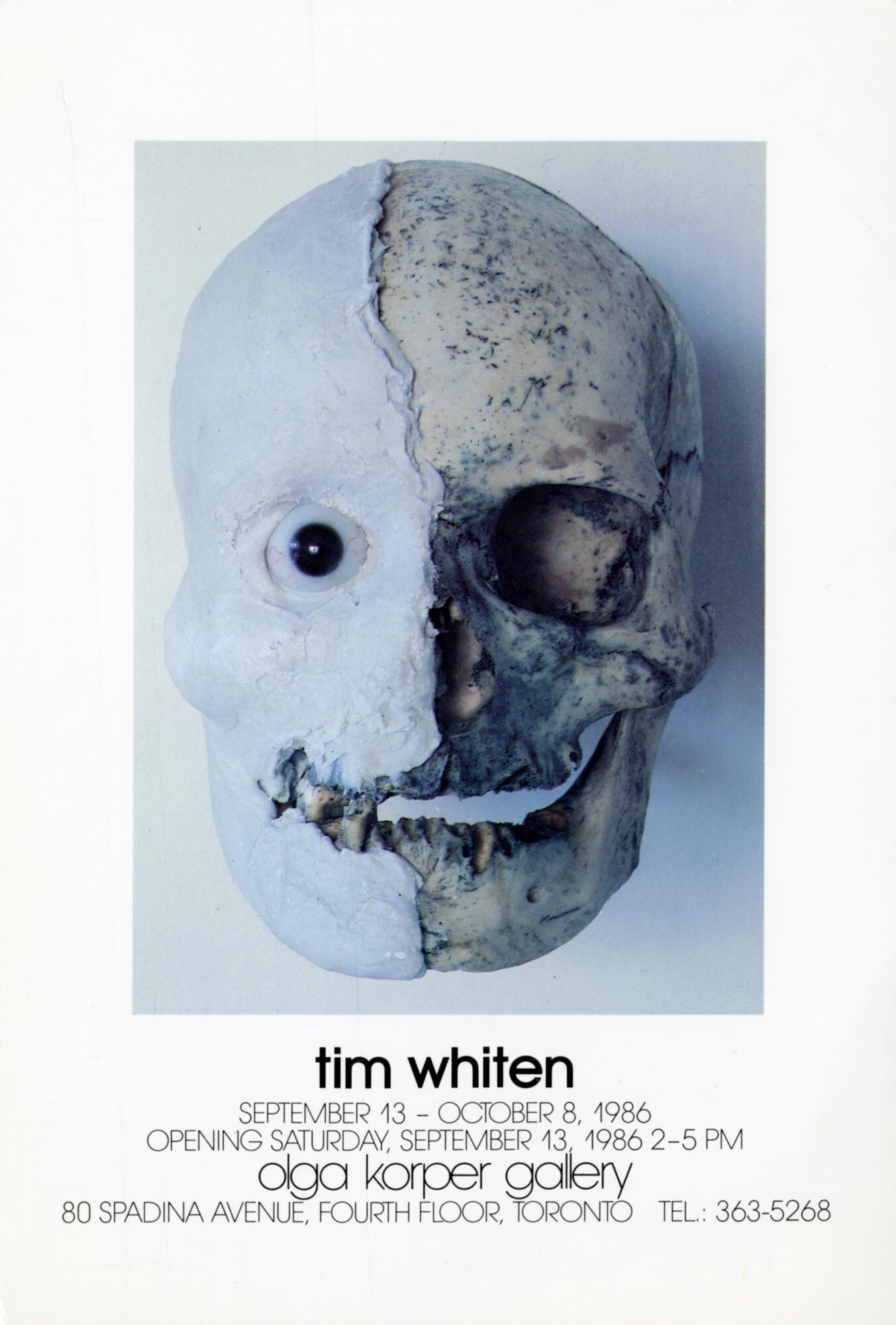

Feeling Whiten might benefit from different representation given his focus on ritual, Herbert (Herb) Sigman, Director of Bau-Xi Gallery in Toronto, introduced him to Olga Korper in 1986. Korper was familiar with Whiten’s practice and had seen his work in Ontario Now 2: A Survey of Contemporary Art at the Art Gallery of Hamilton (AGH) in 1977, curated by AGH Director Glen E. Cumming. An enduring affiliation developed. Korper remains Whiten’s commercial dealer and a close friend to this day.

Whiten has long considered himself as an “image maker” rather than as an “artist.” As he states, “What I make I consider to be cultural objects. The work that I do comes from awareness of my everyday experience.” He recalls, “The relationship with Olga Korper Gallery began with me saying that I was never going to make Art and her reply, which was that she didn’t expect me to.”

Whiten’s work was initially exhibited at Korper’s venue at 80 Spadina Avenue in Toronto, a fourth-floor loft space, until her gallery’s relocation in 1989 to a west-end industrial complex on Morrow Avenue. His first solo show with the Olga Korper Gallery, Descendants of Parsifal, 1986, featured eight human skulls wrapped with various skin-like coverings such as leather, talc, and chewing gum. The series was eventually integrated into Elysium, 2008, commissioned by the AGO for its 2008 exhibition Transformation AGO, and now held in its permanent collection.

Committed to the authenticity of his materials, Whiten has continued to incorporate human remains in his mixed-media works, harnessing the abject properties of these highly evocative materials. Human skulls appear in Ram, 1987, Siege Perilous, 1988, Hearken to the Service of Emmanuel, 1990, and Canticle for Adrienne, 1989, created for his young daughter. The artist’s use of human remains was not without contention. In the spring of 1990, a curator at the Italian Cultural Institute in Toronto removed the two skulls from the armrests of the white throne in Siege Perilous, on view in a group show, after concerns were raised by a visitor about the ethical use of human remains. Public controversy followed. Whiten, however, could substantiate his legal procurement of the skulls with appropriate documentation. After Olga Korper threatened to sue the Institute, the skulls were reinstated.

Several of these pieces were acquired by the AGH, which holds a significant body of Whiten’s works in their collection, including Ram, Siege Perilous, and Canticle for Adrienne. Melissa Bennett, Curator of Contemporary Art at the AGH, comments, “Whiten’s oldest work in the collection, Magic Sticks, 1970, is made of leather and wood, and is a vital foundation to his practice, in his engagement with the notions of ritual and magic and modes of understanding the world.”

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Whiten introduced human hair into his works, including Ch-air, 1992, Elemental, 1993, and Courting the Caliph’s Daughter, 1993. Combining commonplace items (a chair, a frying pan, a cane, an umbrella, a bicycle wheel) with evocative symbols and material vestiges of the life force (hair, bones, teeth, skulls), he produces objects that exude a profound and unsettling presence. In later mixed-media works, human remains are absent; instead, self-reflexivity is generated by the artist’s use of mirrored surfaces to engage and implicate the viewer, evident in Oasis, 1989, Victor, 1993, Vault, 1993, Draw, 1993, and Snare, 1996.

Later Work and Critical Success

I first met Whiten in 1993 at Olga Korper Gallery during his exhibition reception. We were introduced by artist June Clark (b.1941), whose work was the subject of a forthcoming solo exhibition I was curating for the Koffler Gallery in Toronto. Subsequent conversations led to Whiten’s three-venue collaboration, Messages from the Light, which I organized for the Koffler Gallery in 1997, followed by presentations at the Saidye Bronfman Centre for the Arts (now SBC Gallery of Contemporary Art) in Montreal, curated by David Liss, and at Olga Korper Gallery, both in 1998.

-

Installation view of the exhibition Tim Whiten: Messages from the Light, 1997

Koffler Gallery, Koffler Centre of the Arts, Toronto

Photograph by Isaac Applebaum

-

Installation view of the exhibition Tim Whiten: Messages from the Light, 1997

Koffler Gallery, Koffler Centre of the Arts, Toronto

Photograph by Isaac Applebaum

In 1998, Whiten was invited to create a site-specific work at the newly formed Tree Museum, an art park founded by artist EJ Lightman (b.1952) and located on a 200-acre wooded property on Ryde Lake in Muskoka. Sandblasted into the rocky slope of the Precambrian Shield, Whiten’s project incorporated a series of skeletal figures and two constellations of roses—both enduring images in his practice. Danse, 1998–2000, took three summers to complete. For two decades, outdoor installations by Canadian and international artists were created at the Tree Museum during an annual program. While most were temporary, a number remain on view, including Danse.

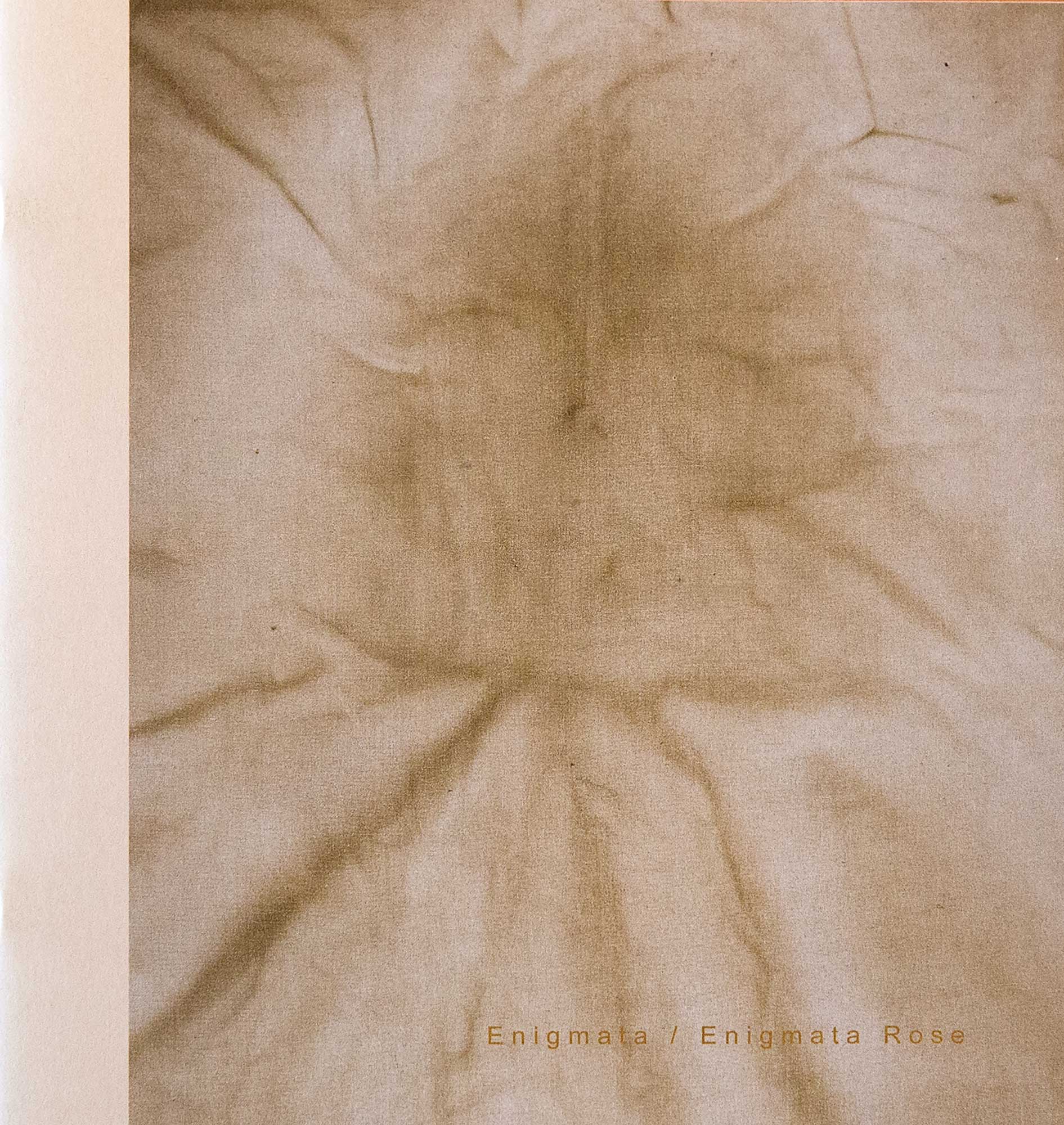

After leaving her position as editor of artscanada in 1982, Anne Trueblood Brodzky returned to the west coast of the United States. She approached Whiten regarding a solo exhibition at the Meridian Gallery, a non-profit presentation and performance space in San Francisco, where she was the founding director. Whiten participated in three successive exhibitions at this venue, curated by Brodzky: Enigmata/Rose, 2001; Working The Unseen, 2004; and Darker, ever darker; Deeper, always deeper: The Journey of Tim Whiten, 2010.

Brodzky also facilitated his participation in the artist residency program at the now well-known Instituto Sacatar, a non-profit arts foundation in Itaparica, Brazil, from 2001 to 2002. During his time in Brazil, Whiten developed an outdoor site-specific work at the Quinta Pitanga and an indoor mixed-media installation for a group show with Brazilian artists. He also completed part three of his seminal Enigmata project, Enigmata/Shower of Roses, 2002. With a characteristic economy of means, Whiten employed coffee-stained hospital sheets to emulate cumulative saturations of bodily fluids, evidence of life’s transmutations. At the centre of two of these series is an image of a rose, a symbol of spiritual love and sacrifice.

During his residency, Whiten immersed himself in Brazilian culture: its art, customs, language, food, music, and poetry. He also formed a deep connection with his African heritage, a kind of “homecoming” experience, especially poignant following the recent death of his mother and the separation from his wife. There, Whiten met Brazilian storyteller Regina Machado, with whom he began a long personal association. She introduced him to the Pierre Verger Foundation in Salvador, where he gained access to Verger’s extensive library of images and ethnographical research of the African Diaspora. Whiten’s interest lay not only in deepening his understanding of his ancestral roots but also in the healing properties of African medicinal plants, coming from a family of healers that included his Aunt Bea.

Since 2002, Whiten’s practice has focused on producing three-dimensional works using glass, recasting objects from daily life, including hand tools (T After Tom, 2002) and children’s toys (Lucky, Lucky, Lucky, 2010, his blue glass rocking horse), as well as those drawn from mythic and religious spheres (After Phaeton, 2013, his glass chariot, and Search Reach Release, 2020, his prayer carpet composed of crushed coloured glass). Employed for its materiality and symbolic function, glass, like mirror, offered the artist a means to address the nature of consciousness and the human condition.

Artist and long-time York University colleague Vera Frenkel comments, “Even before I heard Tim Whiten speak about the complex nature and many qualities of glass, I loved the way it was used in all its states in his work—thick and thin, clear and frosted, hard and soft—evoking different aspects of the spirit. It’s not surprising that his projects attract skilled craftspeople such as the uniquely gifted glass master Alfred Engerer, eager to help realize his vision.”

Whiten’s practice has become the subject of several major exhibitions in Canada and the United States in recent years, including Tools of Conveyance, 2021, curated by Sandra Q. Firmin for the University of Colorado Art Museum in Boulder. In Ontario, a multi-venue collaboration highlighted fifty years of his practice with a focus on alchemy and its transformative processes. Historically, alchemists attempted to purify, mature, and perfect base metals, such as lead and copper, transforming them into noble metals, including gold and silver. Their allegorical pursuit of perfection of the human body and soul is also referred to as the “Great Work.”

The first of these four exhibitions was Elemental: Ethereal, 2022, curated by Pamela Edmonds for the McMaster Museum of Art in Hamilton. It featured Whiten’s three-dimensional works from the late 1970s onward, reflecting his metaphysical interests with a focus on air, breath, and the spirit as captured in his glass works. Elemental: Oceanic, 2022, which followed, was curated by Leila Timmins for The Robert McLaughlin Gallery in Oshawa. This exhibition presented sculptures and works on paper from the early 1970s to the present, representing Whiten’s material explorations of ritual, embodiment, ancestral knowledge, and transcendence. The third presentation, Elemental: Earthen, 2023, curated by Chiedza Pasipanodya for the Art Gallery of Peterborough, included early and recent works by Whiten, with antiquities loaned by the McMaster Museum of Art, to explore the element of earth and its associations with home, sustenance, power, transformation, and alchemy.

The fourth and final exhibition, Elemental: Fire, 2023, curated by Liz Ikiriko for the Art Gallery of York University, brought together works on paper and those executed in glass, with a new crushed glass installation entitled Ground Rules, 2023, conflating a temple floorplan with the chalk outline from a game of hopscotch. The premise of Elemental: Fire considers “how the material transformations of fire appear in Whiten’s works as forms of alchemy, risk, play, and energetic power. Often alluding to notions of time and faith through histories of storytelling and spirituality… Whiten’s work returns us to consider primary questions of our bodies, our presence, and our value in this current moment.”

In recognition of his outstanding accomplishments, Whiten received the Gershon Iskowitz Prize at the AGO in 2022 and a Governor General’s Award in Visual and Media Arts for Artistic Achievement in 2023.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements