Takao Tanabe has explored watercolour, acrylic, and oil painting, as well as a range of other mediums, to produce an oeuvre that spans painting, drawing, printmaking, and graphic design. The artist’s early work was largely nonrepresentational, but he expanded his technical range and modified his style through training in Winnipeg, New York, London, and Tokyo. After spending a year in Japan studying sumi-e and calligraphy, Tanabe developed a novel “one-shot” approach to making large-scale acrylic canvases. Through his re-envisioning of Canadian landscapes such as the Prairies and the West Coast, he has created a body of work that reflects his unique perspective.

Abstraction and Figuration

In the 1950s and 1960s, as Takao Tanabe was launching his career in art, he explored nonrepresentational painting through two principal approaches. The first was a painterly, lyrical approach influenced by Abstract Expressionism and its emphasis on spontaneous, gestural forms. A Region of Landlocked Lakes, 1958, is a striking example of this approach. The work seems veiled in mist and hints at a landscape in the title, even as the forms remain elusive. The second approach was a hard-edged, geometric style of painting, such as Early Autumn, 1967, in which strong linear patterns dominate the composition, stressing a flattening of pictorial space. Tanabe’s travels in the United States, Europe, and Japan during this time profoundly impacted the development of these two approaches to painting as he, according to Roald Nasgaard, absorbed disparate influences “in successive waves,” producing “sophisticated and ambitious bodies of work, astutely of their moment but regionally inflected and idiosyncratically unique.“

While attending the Winnipeg School of Art in the late 1940s, Tanabe was introduced to the lessons of Cubism, as seen in a rare ink-on-paper still-life work created in 1954, and abstraction by his teacher Joseph (Joe) Plaskett (1918–2014), who was hired as the school’s principal when he was fresh from studying with American painter Clyfford Still (1904–1980) in San Francisco and German American artist and educator Hans Hofmann (1880–1966) in New York. Still and Hofmann were formative figures for Abstract Expressionism, and while Plaskett struggled to demonstrate their working methods, Tanabe was intrigued. Tanabe’s trip to New York in 1951 gave him the opportunity to study Abstract Expressionism firsthand and energized his commitment to nonfigurative art.

When Tanabe returned to Canada and resettled in Vancouver in 1952, he “began exhibiting interesting paintings in an ‘abstract-expressionist’ style.” These works, such as Fragment 35, 1953, were well enough received that Tanabe was awarded an Emily Carr Scholarship that enabled him to enrol in the Central School of Arts and Crafts in London and to travel around Europe from 1953 to 1955. During this time, he absorbed many styles of British and European art and produced representational works that captured the landscape and architecture of his new surroundings. Tanabe also continued to study and experiment with methods in abstraction. In London, Tanabe met with artists like Roger Hilton (1911–1975), a pioneer of post-war abstract art in Britain, and Patrick Heron (1920–1999), whose painting and writing promoted modernist ideas.

Through his experiments with form, Tanabe also pushed the boundaries of his media. He had started out using oils in the early days of his career in Winnipeg, and primarily worked in this medium throughout the 1950s. Tanabe was first exposed to acrylic paint while attending the Brooklyn Museum Art School in 1951. Though acrylics were not widely available until the 1960s, they became the artist’s chief means of expression and were later instrumental to the production of his influential prairie paintings.

Tanabe produced his first painting in acrylic in 1961 while living in Vancouver. During the early years of the 1960s (1961–65), Tanabe would sometimes use both oil and acrylic (Lucite) in a work, such as in Small Valley, 1961. He employed the quick-drying acrylic to sketch the basic forms on the canvas, and then, when the surface was dry, completed the composition in oil. Tanabe began to work exclusively with acrylics after 1966.

This shift in materials prompted him to engage more fully with his subject matter, and he began to produce abstract paintings in response to the landscapes around him. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the artist produced a number of abstract landscapes inspired by the rural vistas he glimpsed in Pennsylvania and New York State during his frequent commutes between Philadelphia and New York City. These works, such as The Land III, 1972, and Landscape Study #4, 1972, involve bands of flat, unnaturalistic colour and loosely drawn, soft-edged geometric shapes to suggest forms in the landscape. As Nancy Tousley notes, these transitional works illustrate Tanabe’s emerging endeavour “to paint what he saw, real places in real time, and to do so with minimal distortion.”

Speed, Precision, and Seriality

Tanabe’s move to Banff in the summer of 1972 cemented his belief that he should be painting landscape. But Tanabe was not compelled to paint the mountainous vistas he witnessed daily. Instead, he turned his eye to the Canadian Prairies, a shift in subject matter that required him to reconfigure his approach to painting.

Working from his sketches and photographs of this expansive terrain, he developed new technical and stylistic solutions as he translated prairie scenes onto his canvas. Here, his training in Japan—where he had learned techniques in sumi-e and calligraphy—came into play. With the aid of a grant from the Canada Council for the Arts, Tanabe travelled to Japan between 1959 and 1961. While learning from prominent and respected painters and calligraphers, he began to adopt a method of painting characterized by speed and precision, a necessity when working with acrylics. Tanabe blended his paint with glue until it reached the consistency of table cream and applied that mixture to an unprimed canvas. He approached his materials like a calligrapher, stretching his canvas flat on the horizontal surface of a table, working quickly and discarding any flawed images.

As Nancy Tousley notes, since acrylic paint dries slower than ink, Tanabe’s “window of opportunity was open longer than a calligrapher’s.” But although he extended this window by spraying his canvas with water, he still needed to paint decisively. By “laying down the colours of the land first and letting them dry,” she writes, and “then painting the sky, Tanabe was able to complete even a large prairie painting in forty-five minutes to an hour.“

-

Reference photographs of a prairie landscape enlarged and taped together, n.d.

Photographs by Takao Tanabe

-

Takao Tanabe, Landscape sketch in pencil, 1976

Takao Tanabe sketchbook, Prairies, Morocco, Peru 1976, Takao Tanabe fonds, National Gallery of Canada Library and Archives, Ottawa

-

Takao Tanabe, The Land 20, 1977

Acrylic on canvas, 121.9 x 142.2 cm

Vancouver Art Gallery

Through his paintings of the Canadian Prairies, Tanabe developed his characteristic “one-shot” technique that he honed as he pared down his subject matter, as in The Land 20, 1977. Tousley also explains that the artist approached these works with a lengthy and involved process of planning and preparation: “To select and crop an image to paint from among his photographs and sketches, choose the palette, premix the colours in jars and plan the order in which to lay them down might take Tanabe several days. He then gridded the photograph and transferred the image to a matching grid on the canvas…. When the stripped-down image then met and paralleled the stripped-down essence of Tanabe’s one-shot painting process, the essential quality of each became emphatic.”

In the final step of the painting process, Tanabe unified the painted image, enhanced the sense of space, and sealed it off from the viewer by covering the surface of the painting with a thin wash of black paint. Works such as Prairie Hills 10/78, 1978, and The Land 22/77, 1977, illustrate how Tanabe’s one-shot painting process developed through his lessons with sumi-e, where ink washes conjure atmospheric effects. Tanabe’s use of black wash in Prairie Hills 10/78 is particularly unsettling, evoking a sense of calm before a prairie storm.

The series of paintings made with this technique, produced between 1972 and 1984, changed the way that the prairies and foothills of Alberta were seen by the public. Commenting on what he perceived to be essential qualities of the Prairies, Tanabe explained that “What I think about the prairie is perhaps romantic but it is an enormously simple-looking space and within all that simplicity it’s very, very rich, very subtle.”

Stripped of all human elements, Tanabe’s prairie paintings initially appear to be uncomplicated, with flat bands of colour used to render topographical features. The prairie landscapes are thinly painted, with little to no impasto applied to the surface of the canvas. Through this simplified approach the artist emphasizes flatness as an essential quality of the land. As Tanabe has said, “The prairie that I was painting was flat. As flat a piece of land as I could find and divide it horizontally, sky or clouds, or whatever at the top, a bit of land with a few little subdivisions in it.”

Although there is a serial quality to these works, which Tanabe emphasizes by using a consistent titling convention, the paintings offer subtle, differing views, suggesting a desire to feel connected to the expansive horizons stretched before the eye. Even though Tanabe’s prairie paintings deliberately court the edge of abstraction, they are among the most telling images of the prairie in Canadian art. As Jeffrey Spalding (1951–2019) noted, these works were “hailed nationally as the pervasive trademark image of the west.” But by 1980, Tanabe felt the time had come for a change. He left Alberta and returned to British Columbia.

The Pacific Coast and Layers of Landscape

Tanabe’s return to the West Coast in 1980 prompted a shift in subject matter and brought about gradual changes in the one-shot approach he had developed through his prairie paintings. He became fascinated with the idea of what he referred to as the “layered landscape” and was drawn to how light is rendered in British Columbia’s coastal environments. Tanabe is not particularly drawn to sunny landscapes. Perhaps in response to his childhood, he has said that he is more attuned to misty, grey environments, as can be seen in Westcoast 6/86, Late Afternoon, 1986.

Reflecting on how he has responded to this in his work, Tanabe says that, “The west coast has its bright, clear days where all is revealed, but the views I favour are the grey mists, the rain obscured islands and the clouds that hide the details…. The typical weather of the coast is like that, just enough detail revealed to make it interesting but not so clear as to be banal or overwhelming.“ For Tanabe, an ideal painting of the coast is one obscured by ambient details; an image that does not put everything out in the open, but invites deeper contemplation.

This new scenery necessitated adjusting his painting method to allow for more work on a canvas. In contrast with the quick execution of his paintings of the Canadian Prairies, the West Coast landscapes were executed slowly over months, and many of them have multiple layers of paint. Tanabe has never confined his interest in the landscape of B.C. to one particular region. Instead, he has travelled widely throughout the province, using his camera to document scenes that interest him and that might later be used as the basis for a painting. Documentation is an important part of Tanabe’s practice, but it is also crucial to how he approaches his West Coast landscapes with a relative slowness, a process that enables him to observe deeply the idiosyncrasies of a particular place.

With his West Coast paintings, Tanabe’s goal was to make work that “just appeared” despite all of the time and labour involved in production. As Tanabe has described: “I’ve tried to submerge my artistic idea of being an individual, with individual brush markings…. I’m trying to make it as anonymous as possible. What I wanted was the image to just appear, magically. There is no sense of the energy of the hand putting the paint on the surface and being a mark…. It’s there, it just appears.“

Works such as Strait of Georgia 1/90: Raza Pass, 1990, and Rivers 2/00: Crooked River, 2000, emphasize atmosphere rather than subject matter. However, Low Tide 2/94, Hesquiat Bay, 1994, is perhaps the most remarkable demonstration of Tanabe’s introspective place-based approach to painting. Apparently without “subject,” the work consists of innumerable layers of thinly applied acrylic paint that quietly but convincingly evoke the limpid atmosphere of the coastal air. The work is subtly detailed but never laboured. As Tanabe intended, it seems to just exist. Over forty-plus years, as of 2022 he has produced 435 acrylic canvases that capture the essential West Coast imagery through his particular lens. This body of work situates Tanabe among the most prolific—and, arguably, most profound—painters of the West Coast.

Frames and Framing

Throughout his career, Tanabe has been sensitive to the way that his work is presented. This sensitivity manifests in two ways: in the care with which he executes his paintings, but also in their framing. Since the 1950s, Tanabe has made the frames for his canvases, an activity unusual for an artist of his stature.

In the 1990s, Tanabe produced a group of small-scale acrylic works. In this case, the artist collaborated on the frames with Kevin Kanashiro at the Paul Kuhn Gallery in Calgary. Although not constructed by Tanabe, the frames are absolutely of his choosing and are individualized to each image. Inside Passage, 1994, neatly demonstrates the relationship between the two elements. The work is only 13.5 x 20 cm, but the landscape depicted is grand, with dark hills emerging from each side of the canvas to create the narrow passage evoked by the work’s title. Tanabe chose a silver-leafed wooden frame with a rounded front and asked Kanashiro to use Plexiglas to glaze the work. This careful framing draws the eye towards a vantage point slightly above the water, as if the viewer is aboard a small vessel, looking through the windscreen. The silver frame echoes and amplifies the velvety grey of the cloudy sky.

The frames for Tanabe’s paintings are elegant and understatedly simple. They provide an enclosure and protection for the work but never detract from the power of the painted image.

Printmaker

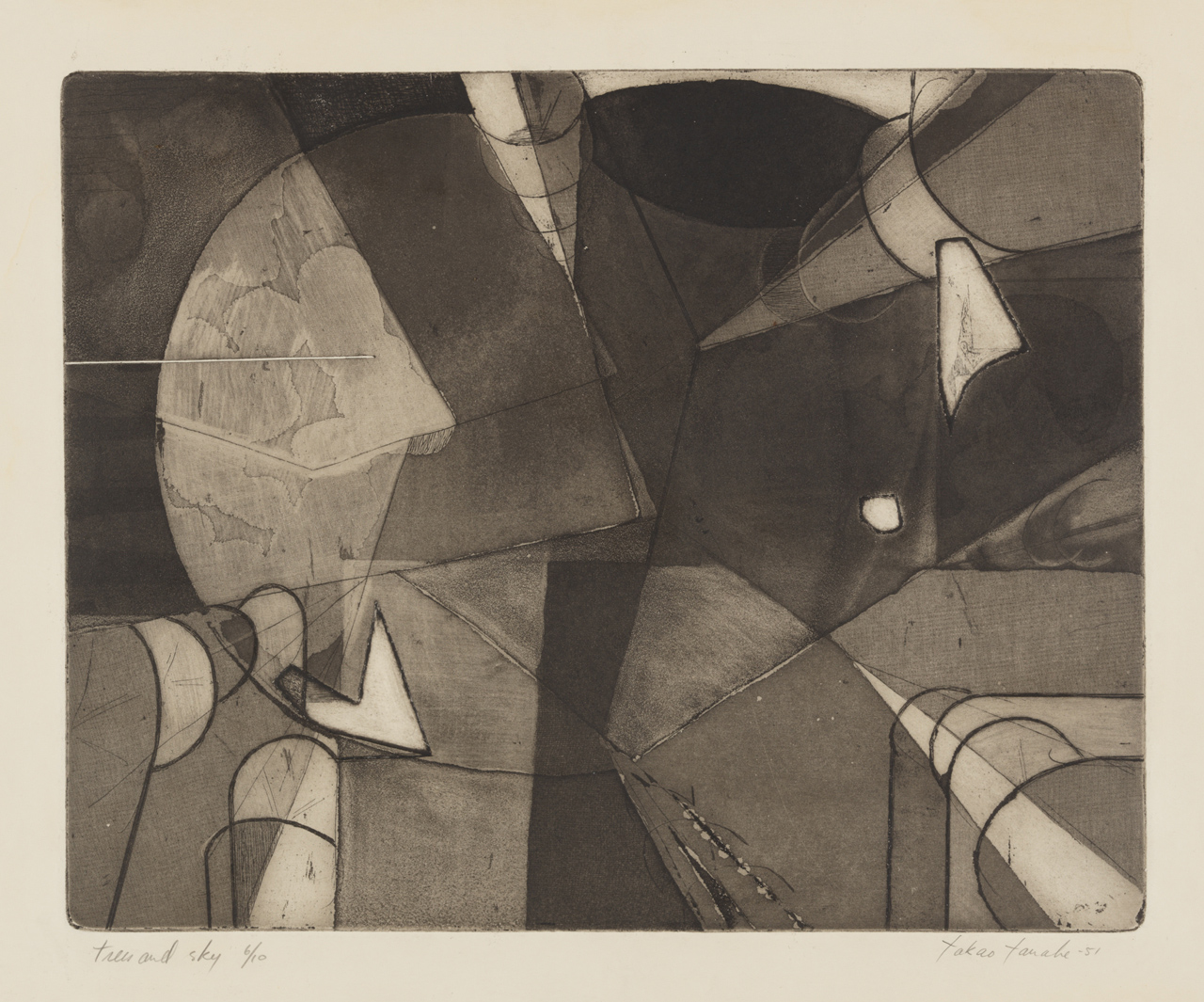

Although printmaking is not central to Tanabe’s practice, he has engaged with it throughout his career, using intaglio methods (etching, aquatint, drypoint, photogravure, and engraving), monoprint, linocut, screen print, lithograph, woodcut, and combinations of these media. When Tanabe took up graphic design and printing in Vancouver in the early 1950s, he was immediately embraced as an important new talent in the field. Within this early body of work, Trees and Sky, 1951, is particularly masterful. The image, which depicts a view up into the canopy, is rendered through subtle and sensitive intaglio techniques of etching and aquatint. The rich colour variations of white, greys, and blacks suggest the natural world while also gesturing to abstraction.

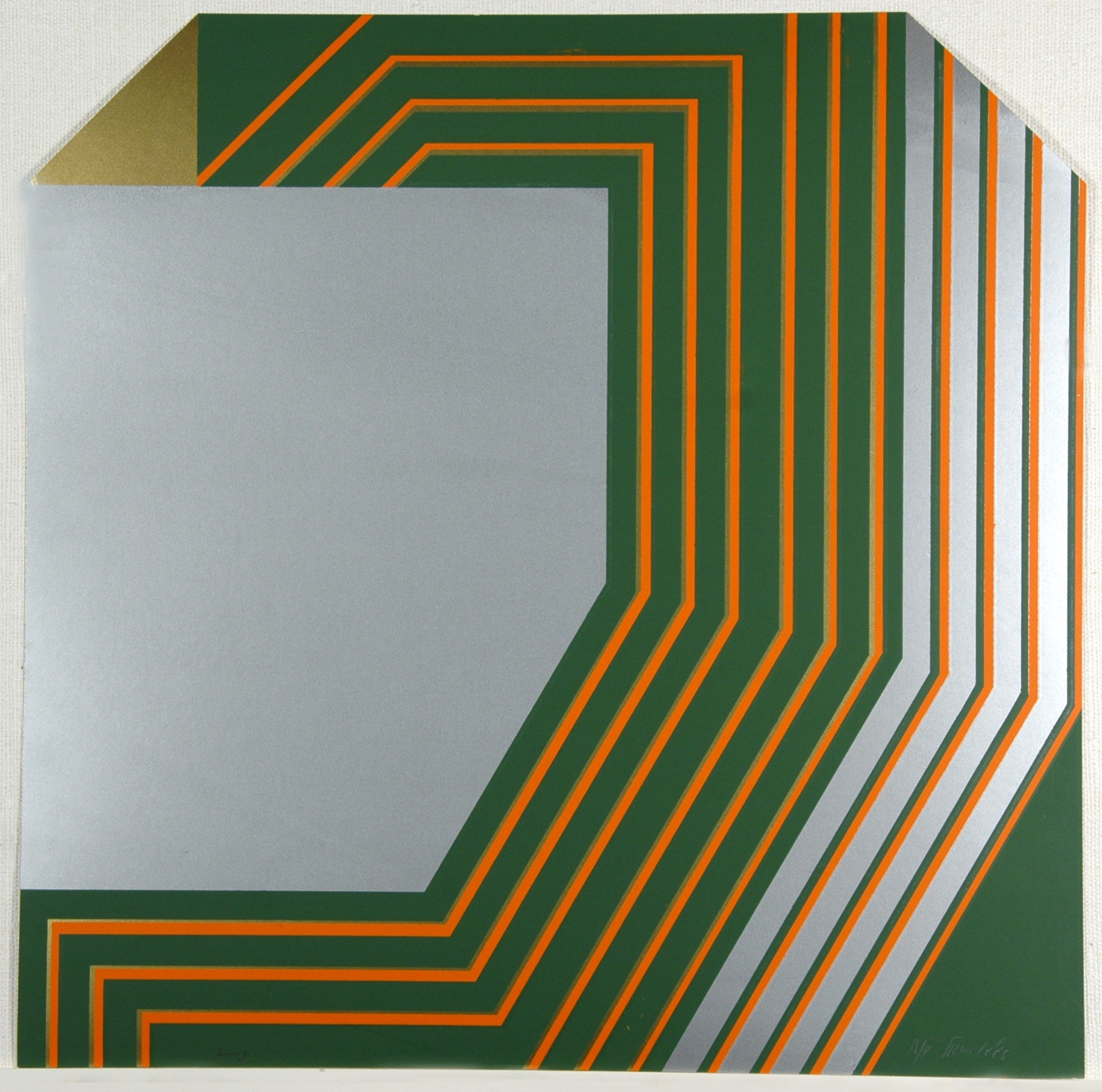

Through his Periwinkle Press, founded in 1953, Tanabe printed letterpress and broadsheets and published several books of poetry, as well as some of his own screen prints. The artist went on to create a remarkable range of prints in a number of styles. Screen prints from the late sixties, such as Wing, 1968, and the Cut-Corners prints of the same year, are both technically adroit and remarkably imaginative in their manipulation of pictorial space. These works were created at a time when Tanabe was experimenting with hard-edge and geometric abstraction, experiments that were reactions to Abstract Expressionism, in which, as Tanabe has remarked, “it was drilled into one that the space had to be shallow, you went in and you had to come out again… I decided [to] make [the space] as complicated as possible, bouncing back and forth, and be completely confusing.”

The approach to space in Wing and Cut-Corners reflects Tanabe’s sentiments about abstraction. Wing confounds our reading of space—it is flat but not flat. The black forms on either side have a solidity that is denied by the inset lines and the vibrating patterns of the central stripe. At times the white passages advance before the black, and all this movement is held in check by the strong horizontal bands at the top of the image. The Cut-Corners prints complicate these spatial ideas further by making the sheet itself an object in space, due to the cutting of the corners. The printed forms echo and sometimes contradict the cut edges. Space in these images is never static.

screen print on paper, 33.1 x 50.8 cm, Vancouver Art Gallery.

As a printmaker, Tanabe has often worked collaboratively. In Banff, he produced many lithographs while working with the printer Jack Lemon (b.1936), as well as a series of woodblocks with the master block cutter and printer Masato Arikushi (b.1947). Since moving to British Columbia, Tanabe has occasionally returned to printmaking with remarkable results. Most significant are his collaborations with Arikushi, beginning with Gogit Passage, Queen Charlotte Islands, 1988. Tanabe’s art is not linear, and rarely do you find hard edges in his landscapes, the exception being a horizon line. So it makes sense that he would work with a block carver and printer such as Arikushi, who did not use linear key blocks.

At first glance, a print like Gogit Passage is deceptively simple. You might imagine the sky is empty, but closer examination reveals vaporous cloud forms. At the left side of the composition is a group of islands, and on the horizon there is an additional series of almost imperceptible islands. The water is a rich mixture of vibrating forms, and Arikushi exploits the grain of the wood to suggest waves. The subtlety of his graduated printing method is seen in the islands, most of which are coloured from light to dark, suggesting the passage of light across the landscape. Note, too, the miniscule, darker islands silhouetted just left of centre. The composition is made up of many elements and does not work unless they collaborate. The precision of the block carving and printing is a tribute to Arikushi’s skill at transforming Tanabe’s image.

The translation of a Tanabe painting into a woodblock was arduous, requiring “up to seven blocks, twenty-seven impressions, and perhaps thirty colours,” and often involved graduated printing, a method that requires the printer to vary the amount of ink on the block so that the colour in the printed image can shift. The woodcuts that resulted from this collaboration are particularly compelling printed images of the coast of British Columbia.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements