Takao Tanabe’s career is largely defined by how he has rethought the landscape genre through reinventing his technique. Although his early years were characterized by his focus on abstraction, he went on to produce paintings that changed the way Canadians viewed the Prairies and the Pacific coast. He was a pivotal figure in arts education as Program Head of Visual Arts at the Banff Centre and, more recently, is a tireless proponent for emerging Canadian artists. Now considered one of the country’s foremost landscape painters, Tanabe has produced an expansive body of work that holds deep resonance for anyone who connects with the landscape of Canada.

Identity and Ancestry

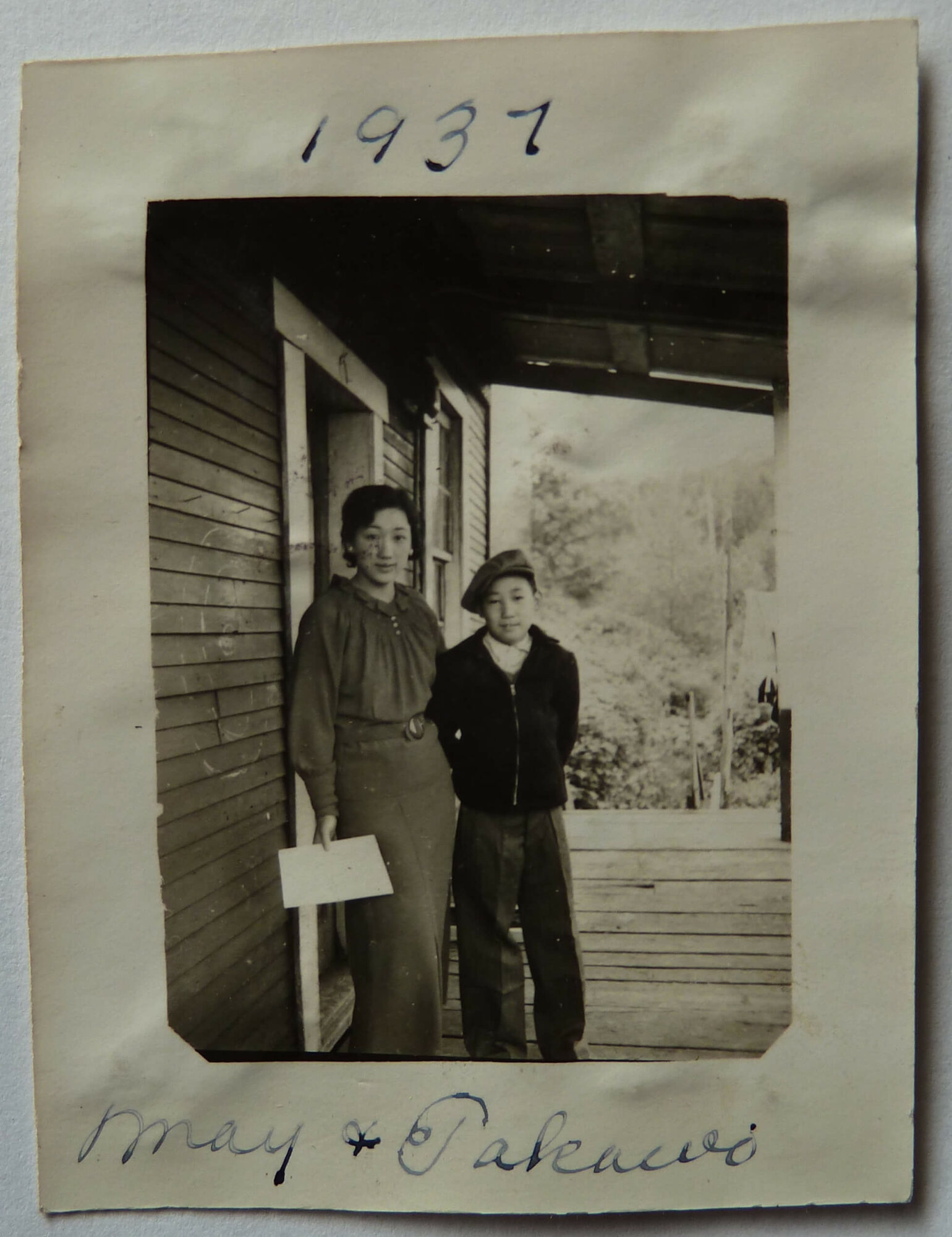

Takao Tanabe’s early childhood was spent in Seal Cove, a small fishing village in British Columbia that was a predominantly Japanese Canadian community throughout the 1920s and 1930s. In 1937, at the age of eleven, Tanabe moved to Vancouver with his family, where they lived until they were forcibly relocated inland during the Second World War along with more than 22,000 other Japanese Canadians on the West Coast. The wrenching events of Tanabe’s internment in the Lemon Creek camp throughout the war exposed him to overt racism that affected every aspect of his life and his family. His identity as a Canadian citizen was suddenly called into question and he had to reassess his place in the world.

Born and raised in Canada, Tanabe did not consider himself Japanese despite his ancestry. However, the experience of forced relocation and internment suddenly made him consider his role as the “Other.” Like many other nisei, or “second generation” Japanese Canadians (many of whom were youths during the war), Tanabe has held complicated feelings about his heritage and his experience of the internment. He was not encouraged by his parents to speak Japanese, nor was he encouraged to learn about Japanese cultural traditions. In turn, he has often vocally resisted the labelling of his art with ethnic or cultural signifiers.

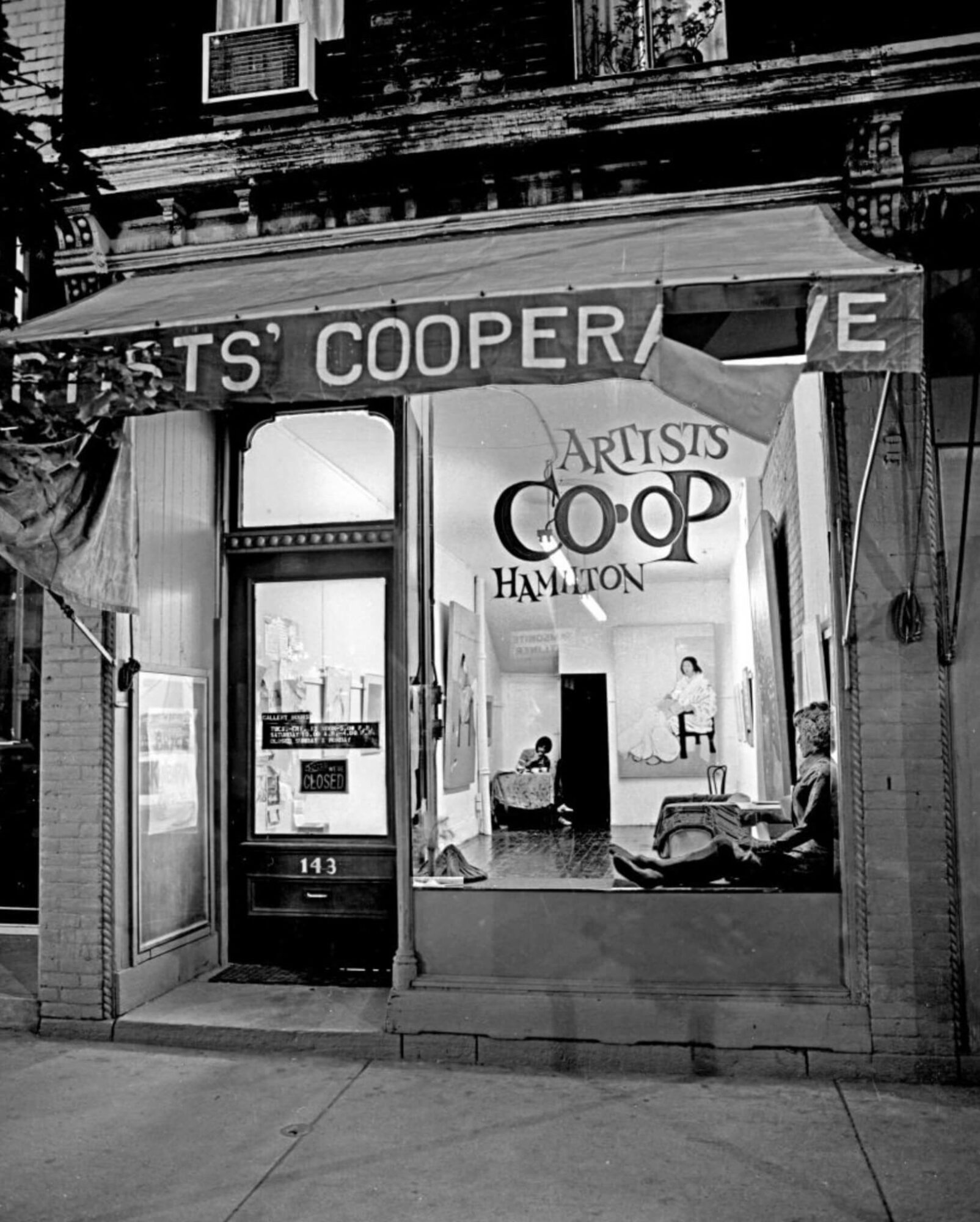

Reflecting on his interaction with Tanabe while organizing the 1987 exhibition Shikata Ga Nai: Contemporary Art by Japanese Canadians at Hamilton Artists Inc., curator and artist Bryce Kanbara (b.1947) notes: “When I asked Takao Tanabe to take part, he replied, ‘It is not the most thrilling idea, another ethnic grouping…. You give no cogent reason for organizing such an exhibition at this time, is there any?’” Despite this response, Tanabe did send Kanbara a painting to be included in the show.

Early in his career, Tanabe began to travel extensively, spending time in New York and Banff and roaming all over Europe. These travels allowed him to produce a significant body of work—notably including drawings like Moni Vatopedi, Mount Athos, 1955—but they did not influence critical thinking about his identity. Still, as early as 1953, when he was creating abstract works, Tanabe’s teacher and mentor Joseph (Joe) Plaskett (1918–2014) remarked that Tanabe was beginning to develop a painting style that had “entered a region of calligraphy,” which Plaskett attributed to “Tanabe’s Japanese ancestry.”

As he was beginning to gain recognition, in 1959 Tanabe received a Canada Council grant that enabled him to travel to Japan for the first time. There, over the course of two years, he would confront his identity. The trip provided him the opportunity to experience Japanese culture, see much of the island nation, and, more importantly, study both calligraphy and sumi-e. This training was valuable in that it equipped him with new tools as an artist and he produced numerous works on paper, such as Forest and Sun, 1960, and Near the Sea, 1960, that were presented together in a 2016 exhibition at the Nikkei National Museum & Cultural Centre in Burnaby, B.C. His time in Japan also led him to question the racialized borders placed between “Japanese” and “Canadian” within a new context. As Tanabe later said, “I realized that my attitudes, my beliefs, everything, I’m a Westerner. I’m a foreigner [in Japan].” He was first and foremost an artist; secondly, he happened to be a person of Japanese Canadian ancestry.

Despite his feelings of foreignness in Japan and his conviction that his ancestry was not overtly significant to his art, Tanabe’s achievements as an artist are deeply meaningful to members of the Japanese Canadian community. Bryce Kanbara has identified Tanabe, Kazuo Nakamura (1926–2002), and Roy Kiyooka (1926–1994) as the “triumvirate of senior Japanese Canadian artists” and the 2022–23 exhibition he organized at the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, Start Here: Kiyooka, Nakamura, Takashima, Tanabe, paid tribute to Tanabe’s and his peers’ accomplishments. Kanbara is mindful that these artists are not creatively affiliated, nor were they deeply aware of one another’s work, but together “they set the bar high for succeeding generations of Japanese Canadians in the arts… and provide all of us with inspirational examples of what it takes to make a difference.”

Innovative and Magisterial Landscapes

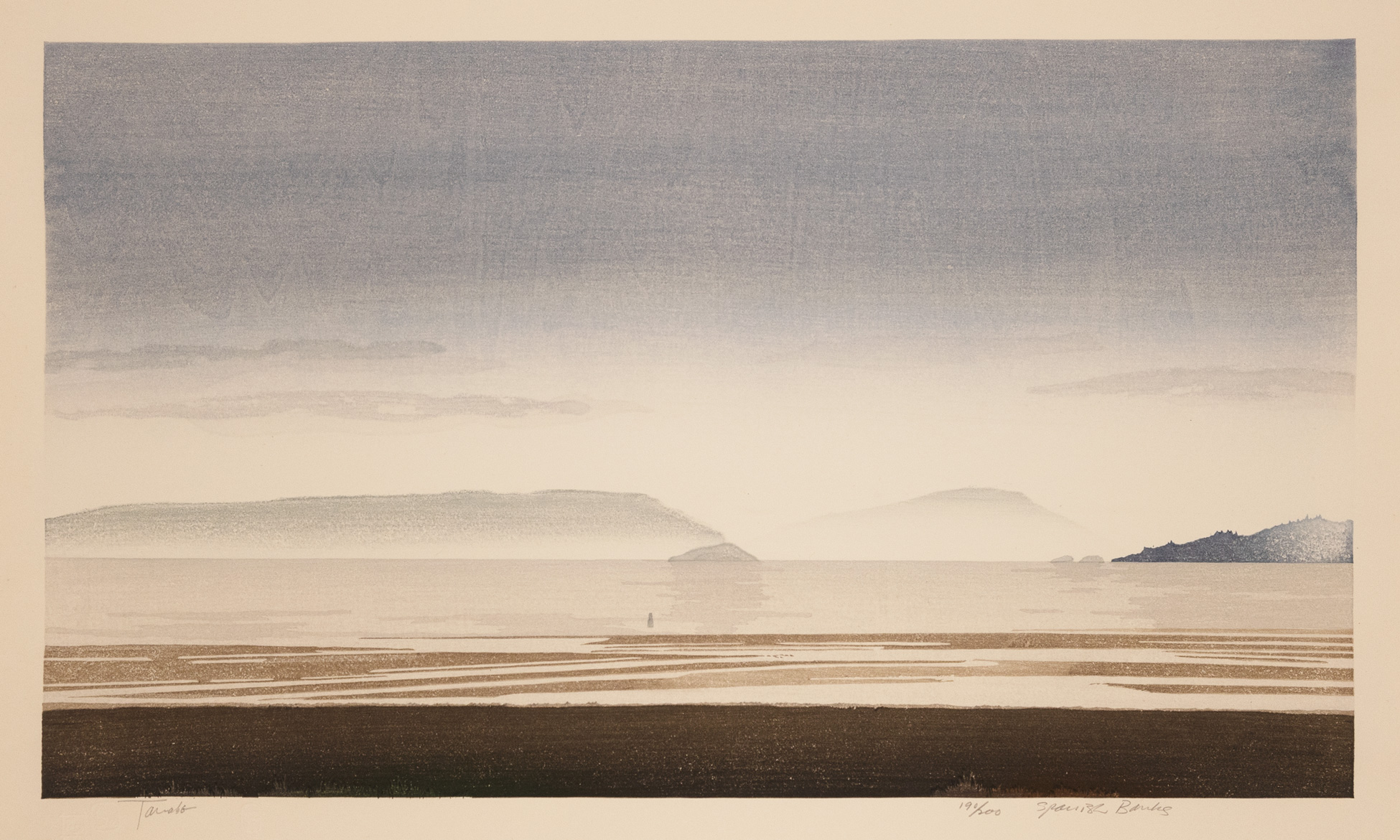

Takao Tanabe has gained national renown for two bodies of work. The first is his long series from the 1970s that took the Canadian Prairies as subject matter. Tanabe’s drawings and paintings of the prairies, such as The Land #6, 1974, have been described by curator Darrin J. Martens as “some of the most challenging, thought provoking, and evocative [works] based on the prairie landscape ever created.” The second body of work includes his depictions of British Columbia’s interior and coast, such as South Moresby 2/86: Kunghit Island, 1986. These subjects have been in production ever since the artist moved to Vancouver Island in 1980. Together, these two series have forged Tanabe’s reputation as one of Canada’s foremost landscape painters.

Following his training in Winnipeg and work with Joe Plaskett in the late 1940s and early 1950s, Tanabe assumed that he would be an abstract painter, but interestingly, his work, despite its non-objective forms, was often read by others as alluding to landscape. Tanabe acknowledges that there is always a link to the landscape and the natural world in his work. The challenge for him was to engage with this subject in new and authentic ways.

Canada has a long tradition of landscape painters. In the nineteenth century, Lucius Richard O’Brien (1832–1899), John Arthur Fraser (1838–1898), and others associated with the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) helped define the young settler nation. In the twentieth century, the works of the Group of Seven further defined landscape as an artform that carried a strong sense of national identity. But although the CPR painters in the nineteenth century and the Group of Seven in the twentieth century embraced the land as a specific subject matter by documenting its scenic grandeur, Tanabe has rejected specificity in favour of a more distilled, essential landscape.

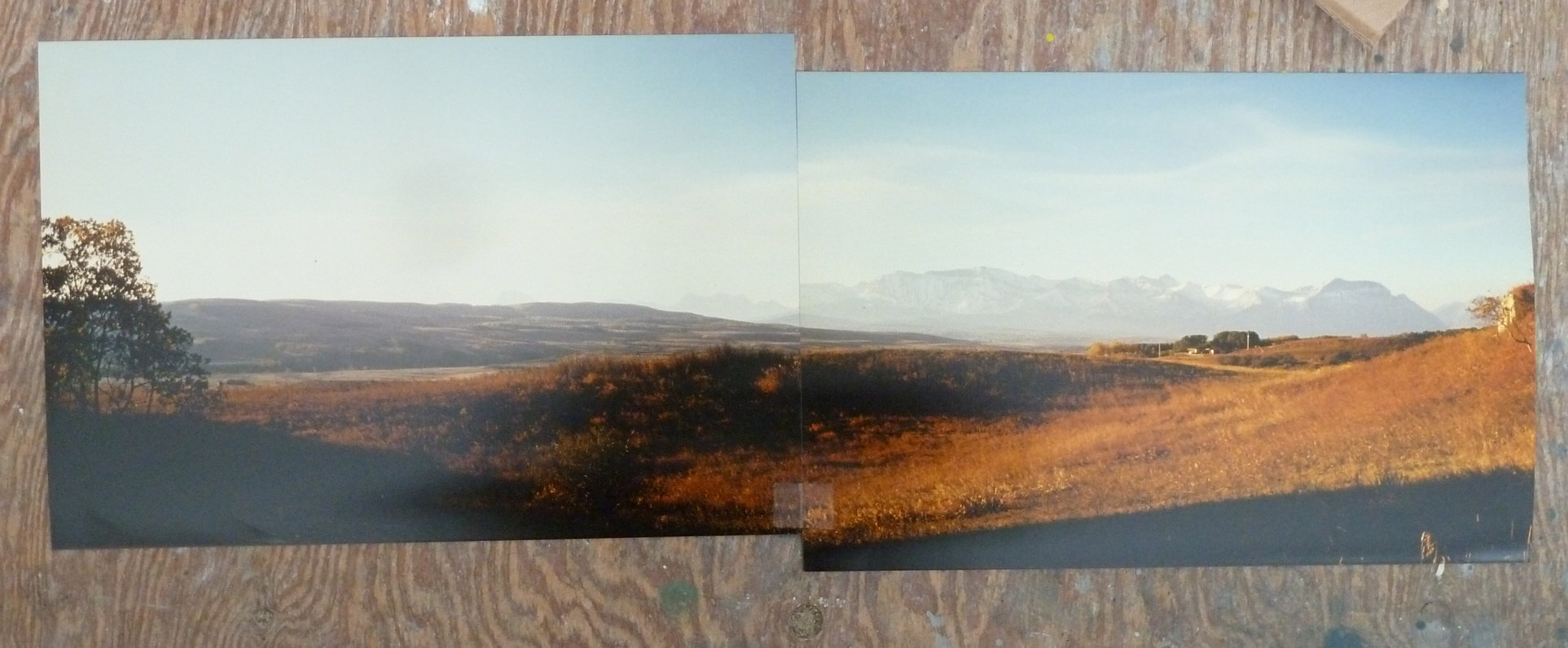

After a period of more than twenty years producing abstract paintings, such as Nude Landscape I, 1959, in the 1970s Tanabe turned to the vast expanses of the Canadian Prairies to tackle the subject of landscape more concretely. He had already hitchhiked across this open terrain in the 1950s, when he commuted between Winnipeg and Banff, and his impressions from that time were lasting. In 1972, he hitchhiked along the same route, stopping to sketch and photograph the vistas that caught his attention and capturing the effects of light at different times of day.

Over the next several years he produced a series of more than two hundred paintings of the prairies, which, through his novel “one-shot” approach, allowed him to explore the edge between abstraction and representation in uncharted territories. Tanabe presented the prairie landscape in a way that was entirely new. As Plaskett commented: “One of the most original things that he’s done is his interpretation of the prairie landscape and that had never been properly done before…. It is a kind of purity that Tak sees in these vast spaces. That he is able to miraculously translate to the canvas. That I think is a unique contribution.”

Earlier traditions of painting the prairies had shown the vast landscape as it related to people. One sees this in works by Lionel LeMoine FitzGerald (1890–1956) and C.W. Jefferys (1869–1951), where people or buildings commonly appear as integral elements of the composition. More contemporary depictions of the prairie landscape by Dorothy Knowles (1927–2023), such as The River, 1967, depict the landscape in more detail. Tanabe, in contrast, sees the prairie landscape as unpeopled and almost abstract; the landscape as a pictorial challenge. Compositions such as The Land 4/76, 1976, and The Land 22/77, 1977, reveal his unique approach.

Tanabe continued painting the Prairies until 1984, but as early as 1976, the Norman Mackenzie Gallery at the University of Regina recognized the significance of the series with a major touring exhibition, Takao Tanabe, 1972–1976: The Land, which travelled to Winnipeg, Saskatoon, Calgary, Victoria, and Edmonton. A 1976 review in the Winnipeg Free Press proclaimed: “Tanabe’s reduction of its panoramic dimensions into a formal essence brings new meaning and clarity to the prairie experience.” His evocative depictions of this iconic region continue to captivate audiences across the country.

Tanabe’s return to British Columbia in 1980 was personally meaningful, but it also marked a huge change in his subject matter and career path. He had explored how to represent the Prairies for the better part of a decade, as seen in Prairie, 1973, but now he was challenged to address the landscape of British Columbia—a subject that was central to the art history of the region. The tradition of Emily Carr (1871–1945), E.J. Hughes (1913–2007), Gordon Smith (1919–2020), and Jack Shadbolt (1909–1998), to name only a few artists, loomed large.

Of these artists, Carr has been the most lauded for her ability to redefine her style and technique in response to the expressionistic forces she witnessed through her travels across B.C. Her career, according to curator, author, and art critic Sarah Milroy, “is an important record of a singular artist’s grappling with that great unanswerable question of the settler imagination: Where do I belong?” Tanabe also needed to find a path of his own. He gravitated to coastal landscapes, such as those seen in Inside Passage 1/88: Swindle Island, 1988, that doubtless recalled his childhood in Seal Cove.

In the 2009 documentary series Landscape as Muse, Tanabe tells a story that connects his paintings to his experiences on the coast, explaining that “I had a brother who was a commercial fisherman who took his boat up from Vancouver to Prince Rupert every year. I decided to hitchhike with him and look at the landscape. I decided it was maybe worthwhile investigating the West Coast and the sea.” However, this retelling does not accurately reflect how Tanabe reached this subject.

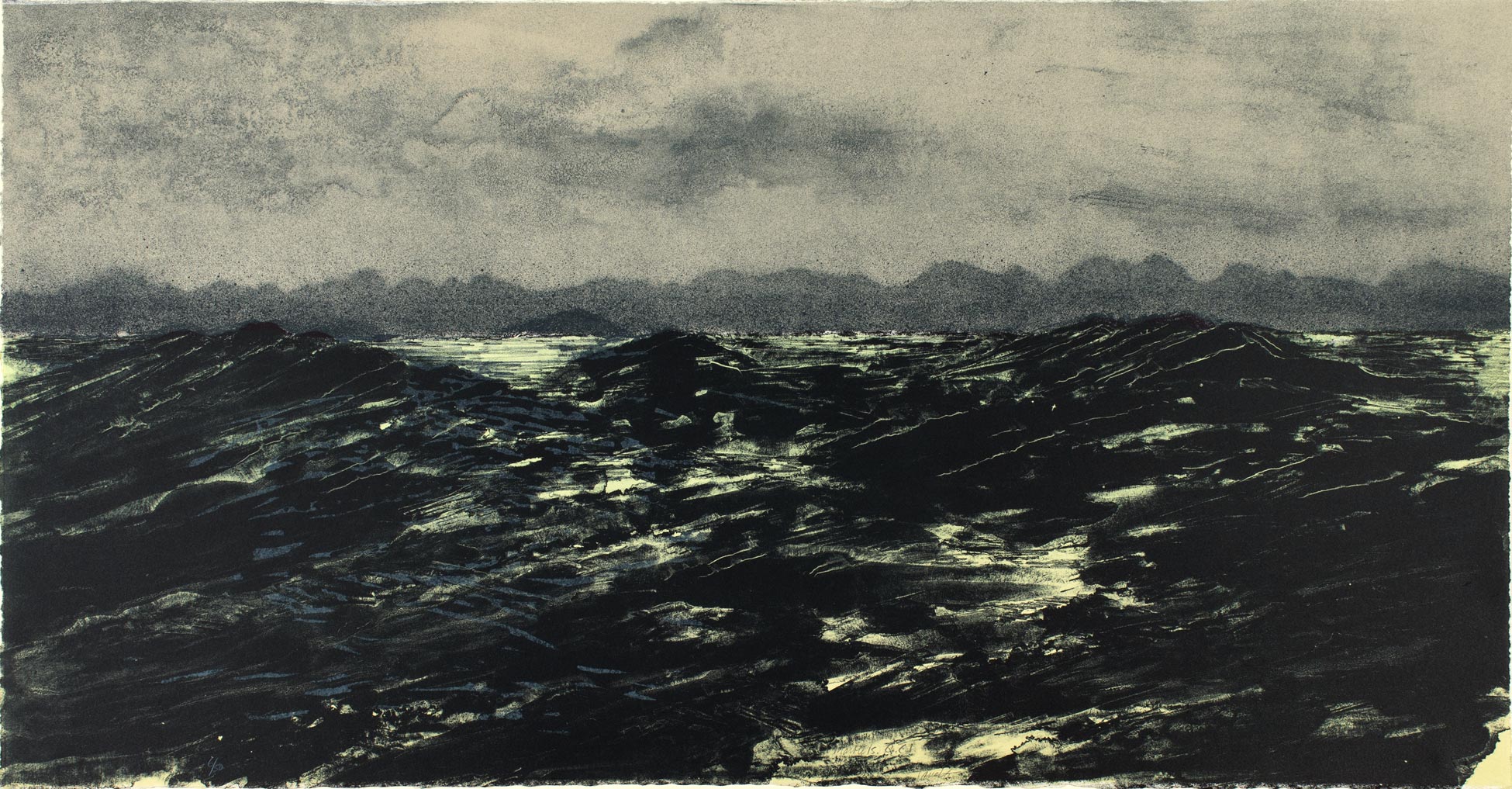

Tanabe did not take the trip up to Prince Rupert with his brother until May 1987, approximately five years after he began to paint images of the Gulf Islands. Further, in 1983, he embarked on an excursion that resulted in a series of canvases and prints depicting the Queen Charlotte Islands (Haida Gwaii). Like many of his works of the B.C. coast, these paintings appear simple in form at first glance, with strong horizon lines and applications of colour used to render the region’s topography. But their simplicity belies the intensive work of evoking the moody qualities of the coast.

Tanabe’s distinct approach to his new subject matter of the coastal landscape was immediately embraced by collectors and the public. His paintings of the West Coast depict “that landscape with a control and magisterial power that no other artist approaches.” With this body of work, Tanabe established himself as one of British Columbia’s most important landscape painters.

Since his return to British Columbia, Tanabe has explored not only coastal scenes but also the province’s interior, as in works such as Peace River 27/99, 1999. His particular and exacting approach to both landscapes was the subject of an exhibition at the Kelowna Art Gallery in 2000, Takao Tanabe: Wet Coasts and Dry Lands. Tanabe sees the ragged weather of this region as “a metaphor for life,” and his ineffable paintings offer a deeply felt meditation on all its mystery.

Tanabe is always supremely mindful of the making of his work. Perhaps paradoxically, his goal is always that the making be invisible to the viewer. This is what marks these works as distinctively belonging to his oeuvre and, in turn, as an important contribution to the story of landscape art in Canada. As Tanabe explains, “I am trying to create new forms based on nature so that I see the world in a new way.”

Educator and Mentor

Tanabe does not regard himself as a teacher and has said that he doubted his ability to get a teaching job due to his lack of university degrees. Tellingly, however, art education has been an integral part of his life. After Tanabe graduated from the Winnipeg School of Art in 1949, he and Don Roy (b.1910) set up a short-lived summer art school in Gimli, Manitoba. He also taught commercial art at the Vancouver School of Art (now the Emily Carr University of Art + Design) in the 1960s, even as his own painting career continued to flourish with both national and international recognition.

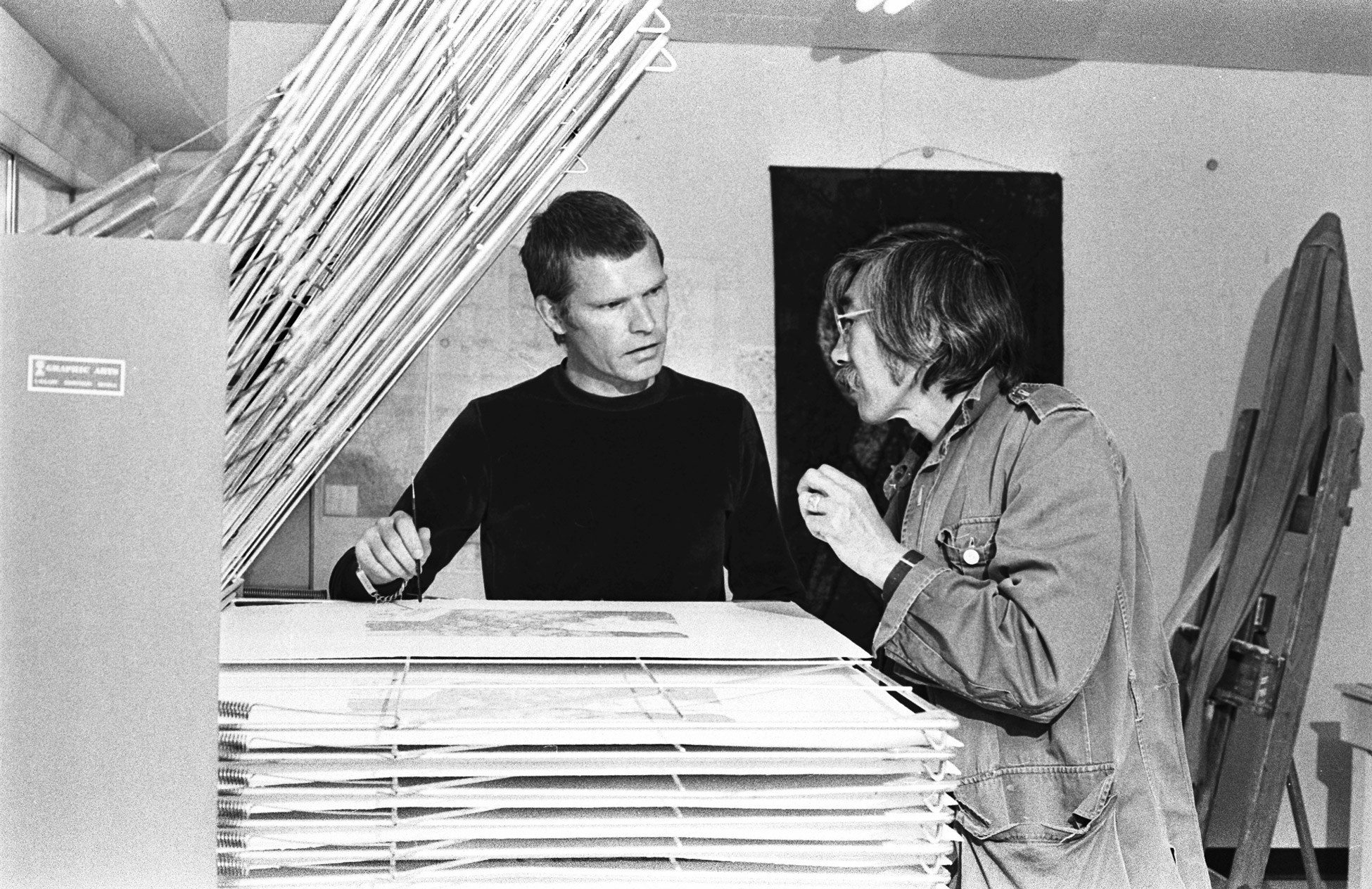

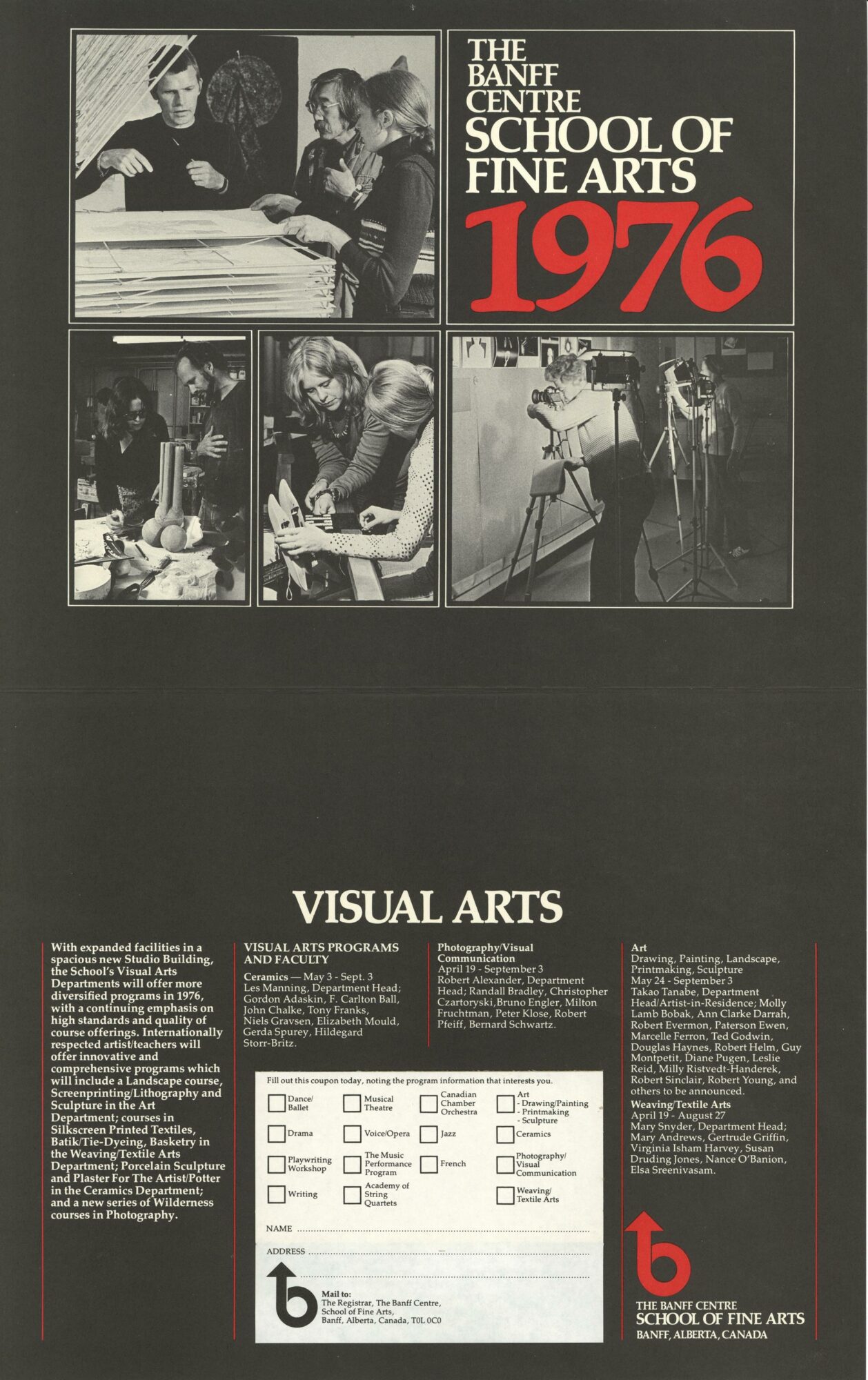

Tanabe’s significance as an educator and facilitator made the most impact during his time at the Banff Centre from 1972 until 1980. He was initially hired as Head of the Painting Division and then appointed Artist-in-Residence in 1973. When he arrived in Banff the program was essentially a summer residency for amateur artists, despite some good teachers. During his tenure, Tanabe helped to grow the school by establishing a year-round intensive program that enabled students to prepare for professional training in Bachelor of Fine Arts programs elsewhere in Canada. Under his guidance and direction, the centre became an important locus for professional artists and those aspiring to become professionals.

His recruitment of a wide range of teachers, including Roy Kiyooka (1926–1994), Ivan Eyre (1935–2022), Claude Breeze (b.1938), and IAIN BAXTER& (b.1936), and his rule that no instructor could return more than twice for the summer session, ensured that the students were exposed to a variety of influences and ideas about artmaking. Tanabe also bolstered the reputation of the Summer School during his tenure by inviting notable faculty such as Joe Plaskett, David Bolduc (1945–2010), Jack Chambers (1931–1978), Ted Godwin (1933–2013), Dorothy Knowles (1927–2023), Marcelle Ferron (1924–2001), and Tony Urquhart (1934–2022).

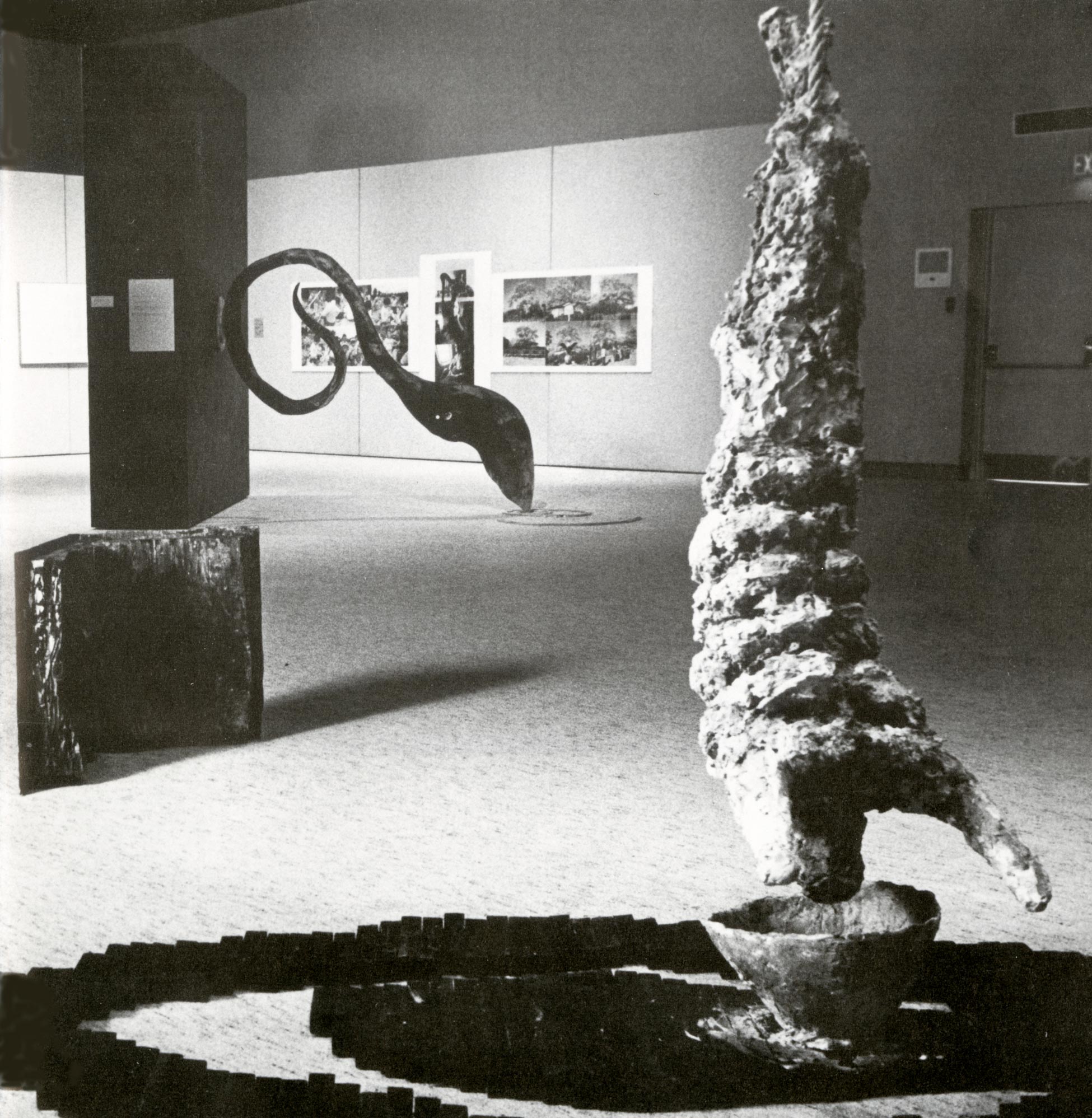

Although Tanabe is primarily a painter, he did not advocate for the development of a single form of art. Throughout his time at the Banff School, Tanabe was an important mentor for a number of artists working in a wide range of media and subject matter, including Alex de Cosson (b.1953), Jack Jeffrey, Cathryn McEwen, Annette Lodge, Marsha Stonehouse, and Barrie Szekely. In light of his tremendous commitment to the program, the rigour and volume of Tanabe’s artistic production through this period is startling. It was during this time that the artist created works such as The Land 22/77, 1977, and The Dark Land 3/80, 1980—two of his most innovative works depicting the prairie landscape.

Tanabe wanted to balance the hard work of running the school with adding valuable experiences for the students and the visiting teachers. The Walter Phillips Gallery, launched in 1976 under Tanabe’s leadership, provided a professional exhibition space for the whole Banff community and an important venue for artists from both near and far. Tanabe revitalized the school throughout the 1970s, and today, the internationally respected Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity (as it is now known) is one of Canada’s leading arts, culture, and educational institutions.

After he left Banff, Tanabe became a key supporter of many artists active in Vancouver. As Landon Mackenzie (b.1954) notes: “Tak has been an important mentor in guiding me to be a serious artist, and to be generous with my peers, encouraging me to take a leadership role, when needed, in the celebration and recognition of other artists who have achieved something.”

Advocacy and Renown

In addition to Tanabe’s dedicated work as an educator, the artist is recognized for his exceptional advocacy for the visual arts. In the 1990s, he began his campaign to establish the Governor General’s Awards in Visual and Media Arts by canvassing individuals and institutions across the country and calling on the Canada Council for the Arts. Launched in 1999, the Governor General’s Awards are among this nation’s most prestigious prizes recognizing artistic achievement, excellence in fine craft, and contributions to contemporary art. Fittingly, in 2003 Tanabe was among the distinguished recipients.

He also played an instrumental role in inaugurating the Audain Prize, which recognizes the lifetime achievement of British Columbian artists. First awarded in 2004, Tanabe was the 2013 winner. The other awards he helped establish in British Columbia through the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria and in Ottawa through the National Gallery of Canada speak to the impact of Tanabe’s leadership and his generosity toward the next generation.

Although he has exhibited widely across his career, it was not until 2005 that a major retrospective, Takao Tanabe, was organized by the Vancouver Art Gallery and the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria. Opening in Victoria, the exhibition then travelled to the Vancouver Art Gallery, the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia in Halifax, and the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in Kleinburg, Ontario. The range of work revealed in the survey was surprising to many viewers. Critic Robin Laurence remarked on Tanabe’s “evolving relationship with the language of abstraction,” his “subtle and evocative depictions of the Canadian prairie,” and the “rainy, grey, mysterious vistas that speak of both primordial creation and primal awareness.” A second retrospective of works on paper (excluding prints), Chronicles of Form and Place: Works on Paper by Takao Tanabe, was organized by the Burnaby Art Gallery and the McMaster Museum of Art in 2011. As all these exhibitions reveal, Tanabe’s art continually challenges our assumptions about his work, the landscape, and how we see the world.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements