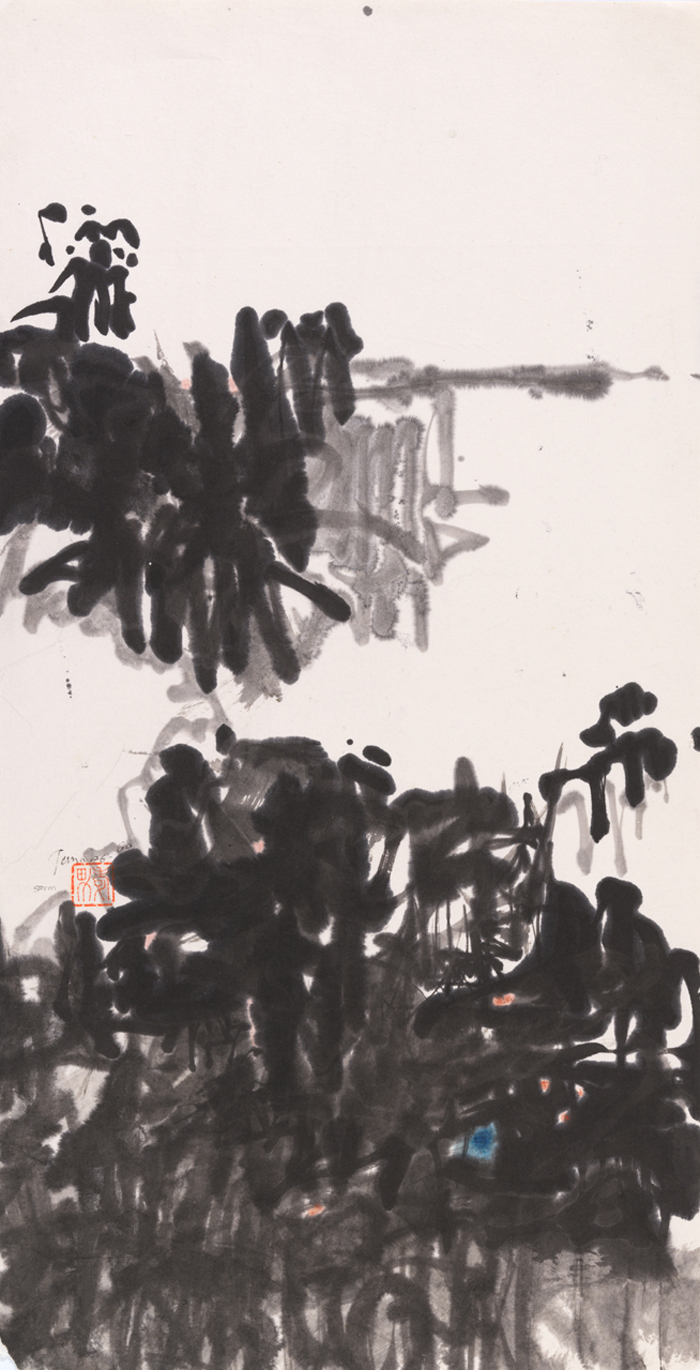

Storm 1960

Takao Tanabe, Storm, 1960

Sumi ink and watercolour on washi paper, 67 x 34.5 cm

Vancouver Art Gallery

A work with remarkably contained energy and spirit, Storm is a highly abstracted landscape with trees below and cloud above. The cloud in the upper portion of the composition contains saturated black pigment in the brush strokes on the left and paler grey passages on the right. The shimmering pigment suggests the atmospheric movement that storms bring, and yet a complex series of painterly actions can be seen in the work. There is both depth and flatness; the three small spots of pink and blue hint at three-dimensionality.

Tanabe created this work with the newfound confidence he developed during his first, influential trip to Japan in the late 1950s. For this work Tanabe uses Japanese sumi ink and paper, but the vigorous calligraphy of the brush strokes evokes the work of Abstract Expressionists like Franz Kline (1910–1962) rather than Japanese painting traditions. Sumi ink, made of either burned rapeseed or pinewood soot, is thinned with water and allows for an almost infinite variety of shades between deep black and pale greys. In Storm, the range of sumi ink shades are clearly seen.

In 1959, Tanabe had received a Canada Council grant that allowed him to travel to Japan, and he stayed in Tokyo between 1959 and 1961. The artist had two reasons for visiting the country. As a person of Japanese ancestry uprooted from his home and placed in an internment camp during the Second World War, Tanabe was unsettled in his relationship to his heritage. In his own words he asked, “Was I Japanese?”1 He believed that this trip would help determine that. The second and artistically important reason for Tanabe’s journey was to study sumi-e, black ink painting, and Japanese calligraphy with master teachers Ikuo Hirayama (1930–2009) and Yanagida Taiun (1902–1990), a calligrapher who worked in the Zen tradition and was known for his large-scale works rendered with a single stroke.

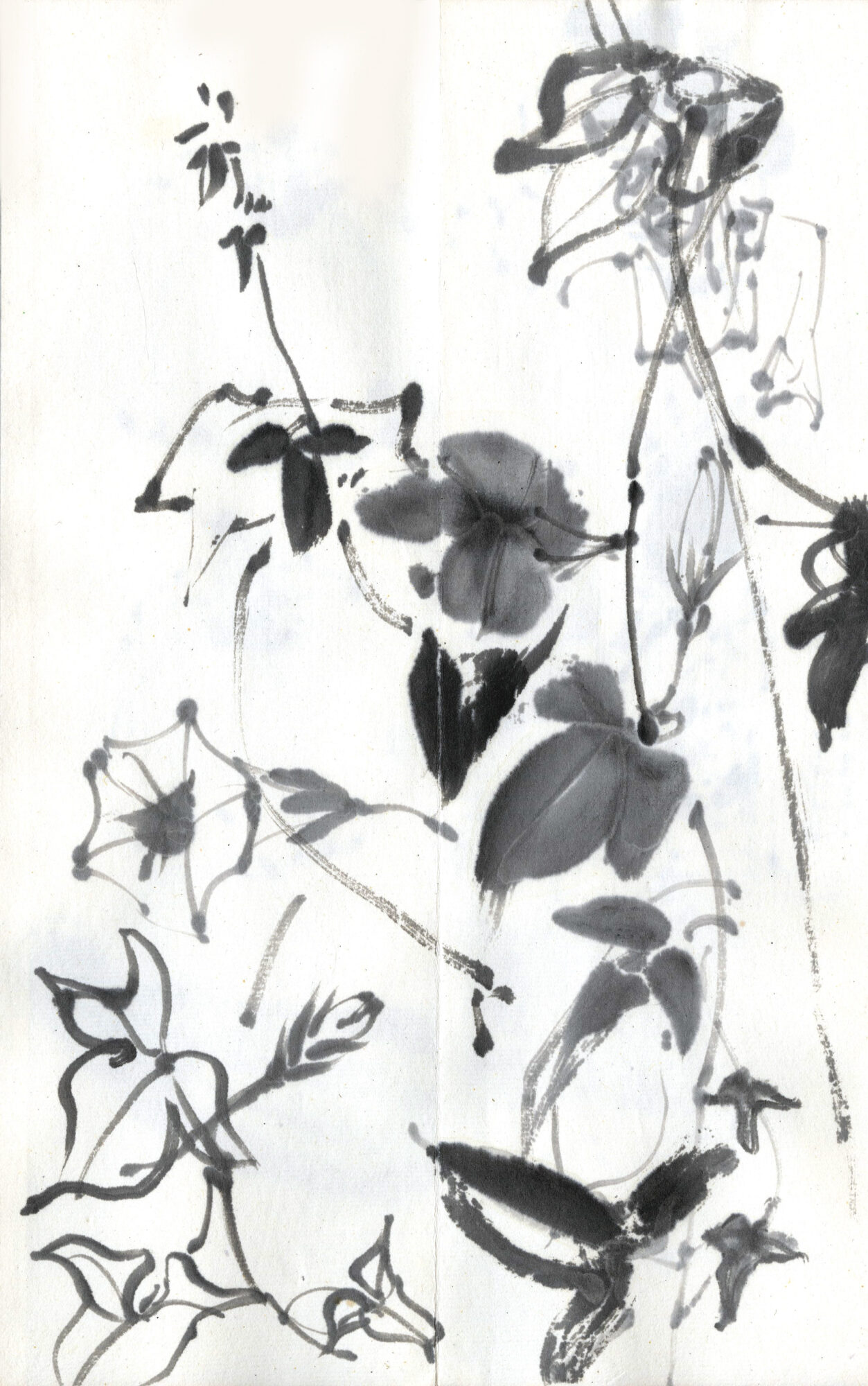

While in Japan, Tanabe produced paintings in more traditional formats, such as Blossoms, 1960, and in more experimental forms, such as Raked Sand and Stones, 1960. Lessons with Hirayama included the copying of specific paintings that showed a certain kind of brushwork, which allowed Tanabe to get a real feel for Japanese brushes and the medium itself. In both sumi-e and calligraphy, the artist must be decisive in their actions. The extreme absorbency of the paper means that no correction is possible. If a mistake is made, the work is ruined.

In 2002, during the process of gifting Storm to the Vancouver Art Gallery, Tanabe wrote:

The primary challenge while in Japan… was to study the sumi-e (sumi ink on a very absorbent paper) and the calligraphic methods of working. What influence, if any, was there on someone like Franz Kline of the Japanese ways of calligraphic works? The very expressionistic, running grass style of calligraphy does have much in common in a superficial way. However, one must remember that no matter how abstracted the strokes of the word, there is still a basic ideogram imbedded in the finished work in calligraphy. To the Japanese there is a meaning, but for us in the west, it is quite devoid of the meaning that begins the process, the ideogram. We see them as abstract work.2

This passage reveals that Tanabe was aware of the influence that East Asian calligraphy and ink painting had on American abstract painters such as Kline and Mark Tobey (1890–1976), who actively promoted the works of modern calligraphers. Tanabe understood that it was precisely because these artists could not read Japanese writing that they were drawn to calligraphy in the first place; they viewed abbreviated and expressionistic styles as nonrepresentational forms. Though Tanabe could not read Japanese calligraphy either, his interest in looking beyond surface-level formal affinities moved him to explore these practices and their contemporary applications.

Although the sumi-e paintings Tanabe produced were, for the most part, confined to his time in Japan, the decisive approach required by the medium afforded him a creative assuredness that would be significant in the execution of his later prairie landscapes.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements