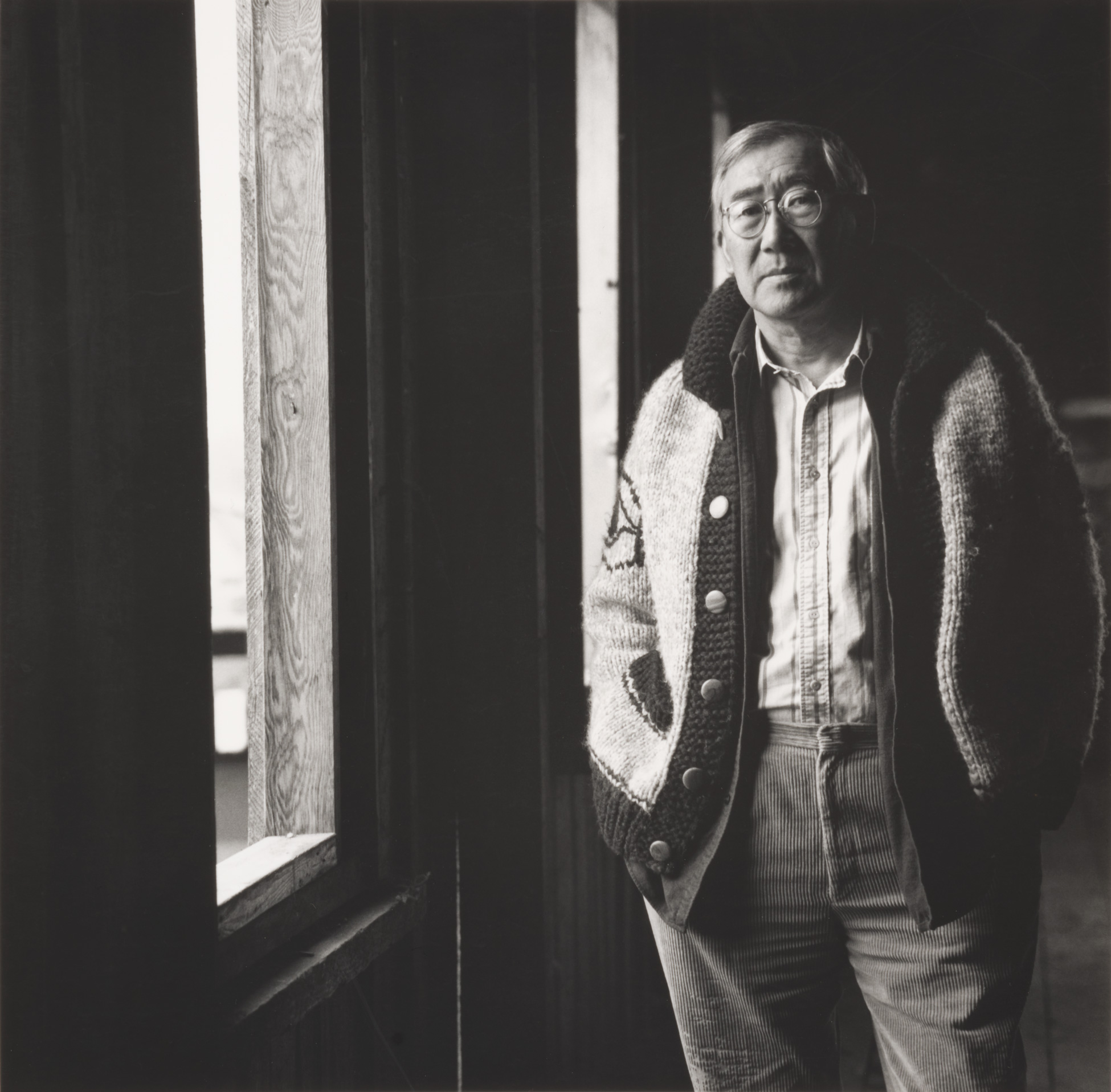

Growing up in a Japanese Canadian family, in the tiny hamlet of Seal Cove, British Columbia, Takao Tanabe (b.1926) had no meaningful access to art or the possibilities it offered. But through a combination of serendipity, tenacity, and inspiration, the events of his extraordinary life sparked Tanabe to discover in painting both a true vocation and a catalyst to learn more about Japanese culture. He overcame early hardships to transform the history of Canadian art, reframing this country’s most distinctive landscapes through his wholly singular vision. As a painter, printmaker, teacher, philanthropist, and advocate, Tanabe has forged a path for new generations of artists.

Early Years and the Second World War

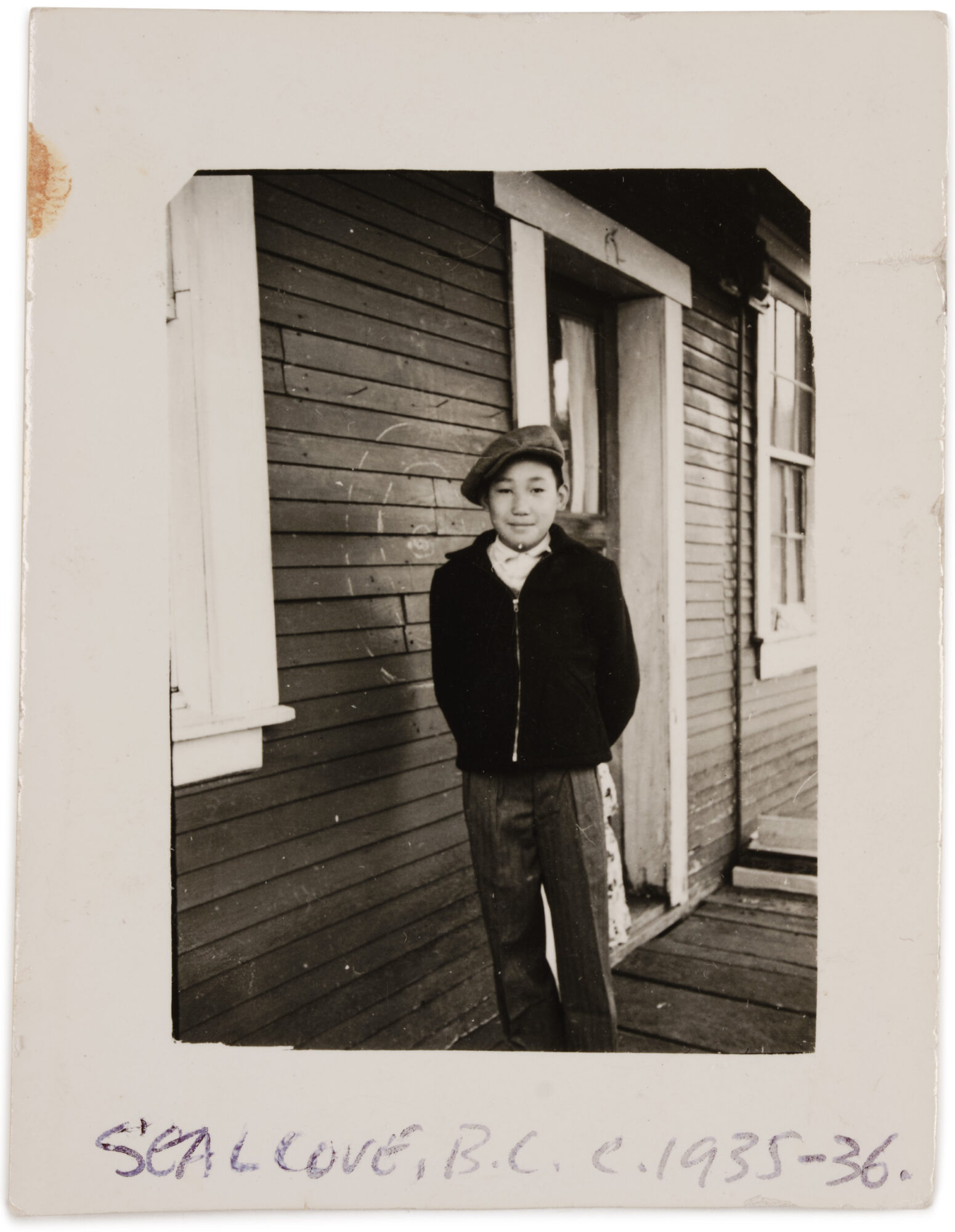

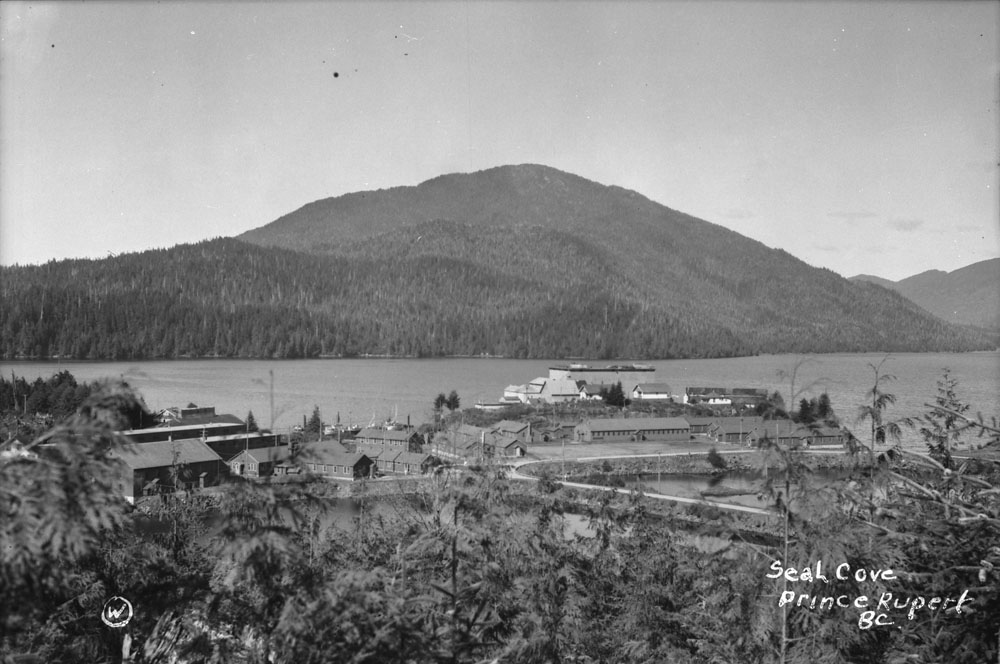

Given Takao Tanabe’s humble roots, and the hardships that coloured his formative years, it is nothing short of extraordinary that he grew up to paint landscapes that transform the way we see Canada. The fifth of seven children, Tanabe was born to Japanese immigrants Naojiro Izumi and Tomie Tanabe in 1926 in the tiny coastal village of Seal Cove, B.C. Now part of Prince Rupert, Seal Cove was a predominantly Japanese Canadian community, and most residents made their living as fishers. Tanabe’s father operated a commercial fishing boat and his mother worked in the local cannery. In 1937, the family moved to Vancouver, where the then eleven-year-old Tanabe continued his schooling. He was midway through high school when, in December 1941, Japanese airplanes attacked the American naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii—a watershed moment in the Second World War, and an event that dramatically altered the course of Tanabe’s life.

Canadian Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King immediately responded to the attack by declaring war on Japan. Officials in B.C. quickly seized all fishing boats owned by Japanese Canadians, implemented a strict curfew that limited their freedom of movement, and shuttered all Japanese language newspapers and schools. In early 1942, the federal government designated a wide strip along the B.C. coast as a “protected area” and declared that all “persons of the Japanese race” living within this area, which extended approximately 160 kilometres inland, would be relocated and their properties and businesses seized.

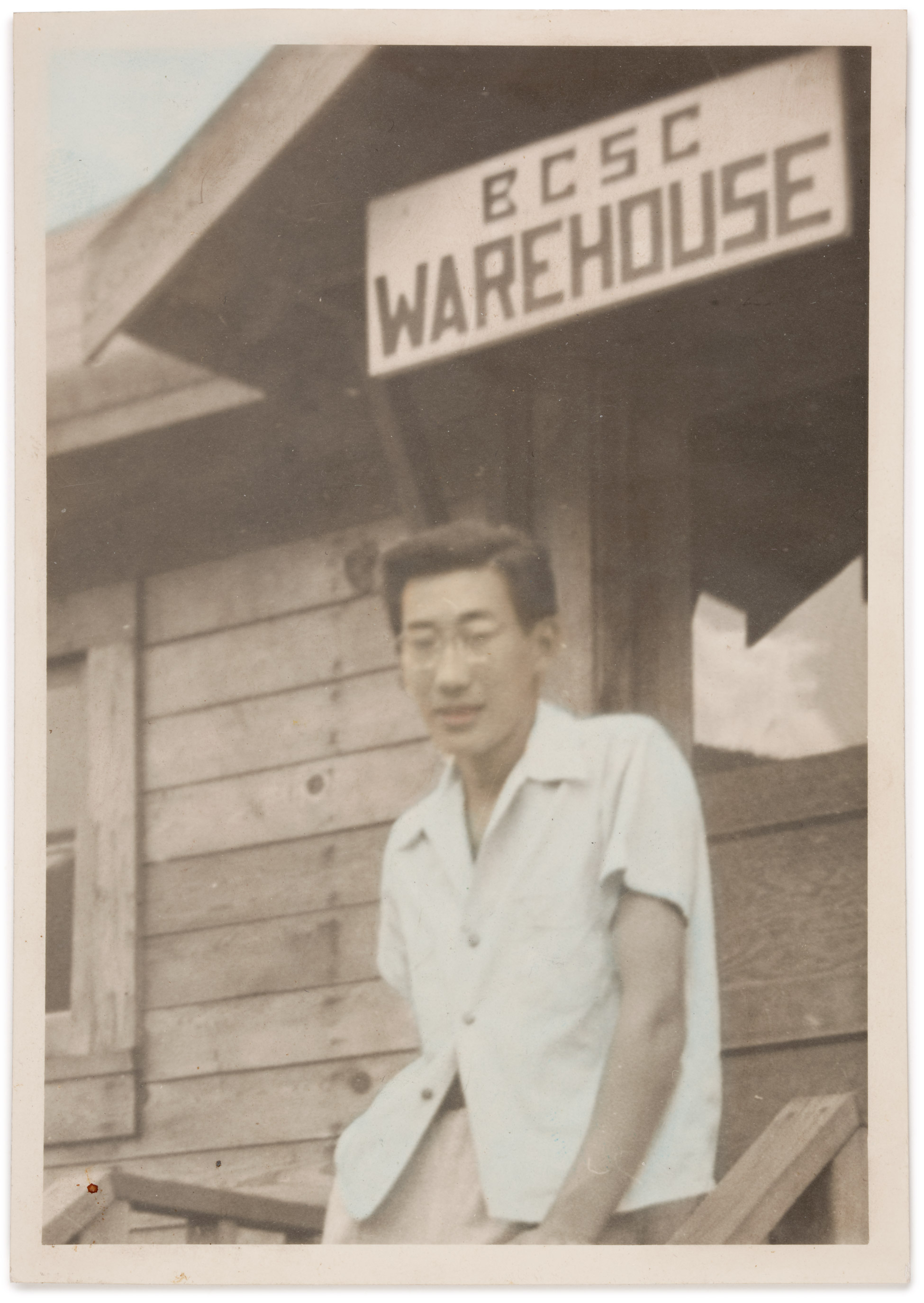

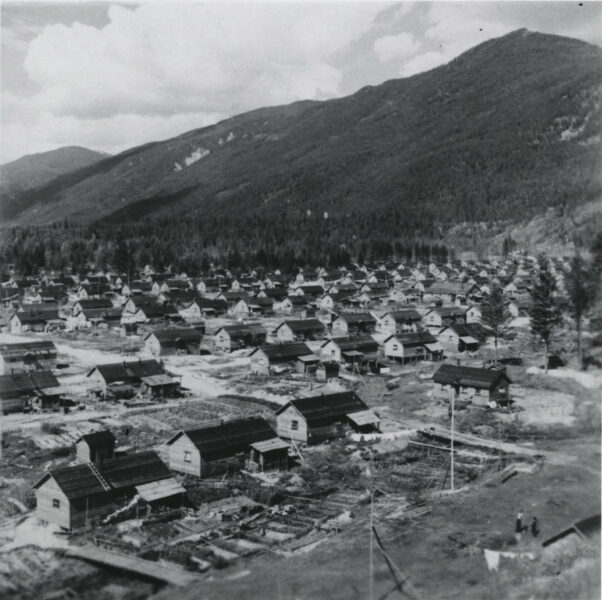

Between 1942 and 1949, approximately 22,000 men, women, and children were displaced from their homes and sent to incarceration sites, including labour camps, roadwork sites, and sugar beet farms, across Canada. To authorize this mass uprooting, King invoked the War Measures Act that granted the federal government the authority to suspend the basic rights and freedoms of Canadian citizens. Efforts to dispossess and intern Japanese Canadians, who were deemed “enemy aliens,” were framed as measures of national security.

In 1942, Tanabe and his family were forced to leave the coast for Lemon Creek in southeastern B.C., where they, along with other Japanese Canadians, were expected to build their own internment camp. For Tanabe, then a teenager, this meant the end of his schooling and the beginning of intense labour. He helped his father build and weatherproof the camp structures and was assigned the specific task of applying tar to the roofs. He and his father also harvested logs from the forest to create an extension for their small cabin. “The alternative,” Tanabe has recounted, “was to go to a farm on the prairies and be indentured for one or two years, which is what two of my older brothers and one sister who was married chose.”

It was a profoundly difficult time. During this period, a British military officer visited Lemon Creek looking to recruit agents for the war effort in Asia. Several of Tanabe’s friends were eager to enlist, thinking it would be an adventure even if they weren’t fluent in Japanese. They encouraged Tanabe to join them, but he refused because this proposition was tantamount to aiding his oppressors. Later, after the war had ended, he made a conscious decision to release his anger about his internment so that he could move forward with his life.

Art School

After the Second World War ended, Japanese Canadians who had been forced to leave the Pacific coast were also prevented from returning home. Their options were limited: resettle east of the Rocky Mountains or be deported to Japan, a nation unfamiliar to the majority of those interned during the war. So, in 1944, Tanabe joined some of his older siblings in Winnipeg, where they worked as indentured farm labourers. He did a stint in a warehouse, cut peat in southeastern Manitoba, and then spent a summer toiling in an iron foundry, but he soon realized that he was not fit for a life of physical labour.

By 1946, Tanabe was contemplating his future, acutely aware that his career prospects were limited by his truncated education. As he has noted, while he reflected on how to save up money, Tanabe also realized he had to figure out where to finish high school: “I don’t know how, but somebody pointed me in the direction of the art school as an alternative.” He discovered that the Winnipeg School of Art was willing to accept prospective students who had not completed high school. Although he had no experience with fine art, Tanabe landed on sign painting as a practical course of study, one that would provide him with employable skills. He enrolled in an evening class, and this decision would prove to be pivotal. Although the course was part of a commercial program, the school also held drawing and painting sessions in the evenings. Tanabe was fascinated by the idea that art could exist outside of a commercial context. Although he had grown up surrounded by magnificent landscapes, Tanabe had never considered trying to capture or reflect that beauty in any way, as the notion of creating art for art’s sake was not something he had encountered during childhood.

He applied to the art school and was accepted, and then spent the next three years as a full-time student. During his first two years, Tanabe offset tuition costs by working in the foundry on weekends. In his final year he took a part-time job as the janitor at the art school. In the mid-1940s, the Winnipeg School of Art was the domain of Lionel LeMoine FitzGerald (1890–1956), but the distinguished landscapist and teacher was preparing to take his leave. Unfortunately this meant that Tanabe never took a class with FitzGerald. But serendipitously, in 1947, the school hired the artist Joseph (Joe) Plaskett (1918–2014), who had just completed a period of study with German American painter Hans Hofmann (1880–1966) in New York.

Plaskett endeavoured to bring the narrative of New York modernism to the Prairie school. He introduced students to the work of Pablo Picasso (1881–1973), Paul Cézanne (1839–1906), and Henri Matisse (1869–1954); he also tried to explain the dynamics of Hofmann’s approach to painting, although that kinetic quality could not be captured in visual aids. Crucially, for Tanabe, Plaskett became a lifelong friend. Early on, he recognized something special in the young student and encouraged Tanabe to trade sign painting for fine art. In Plaskett’s words, Tanabe was “the star” of the school: “He had the real talent…. He was my best pupil. Outstanding.”

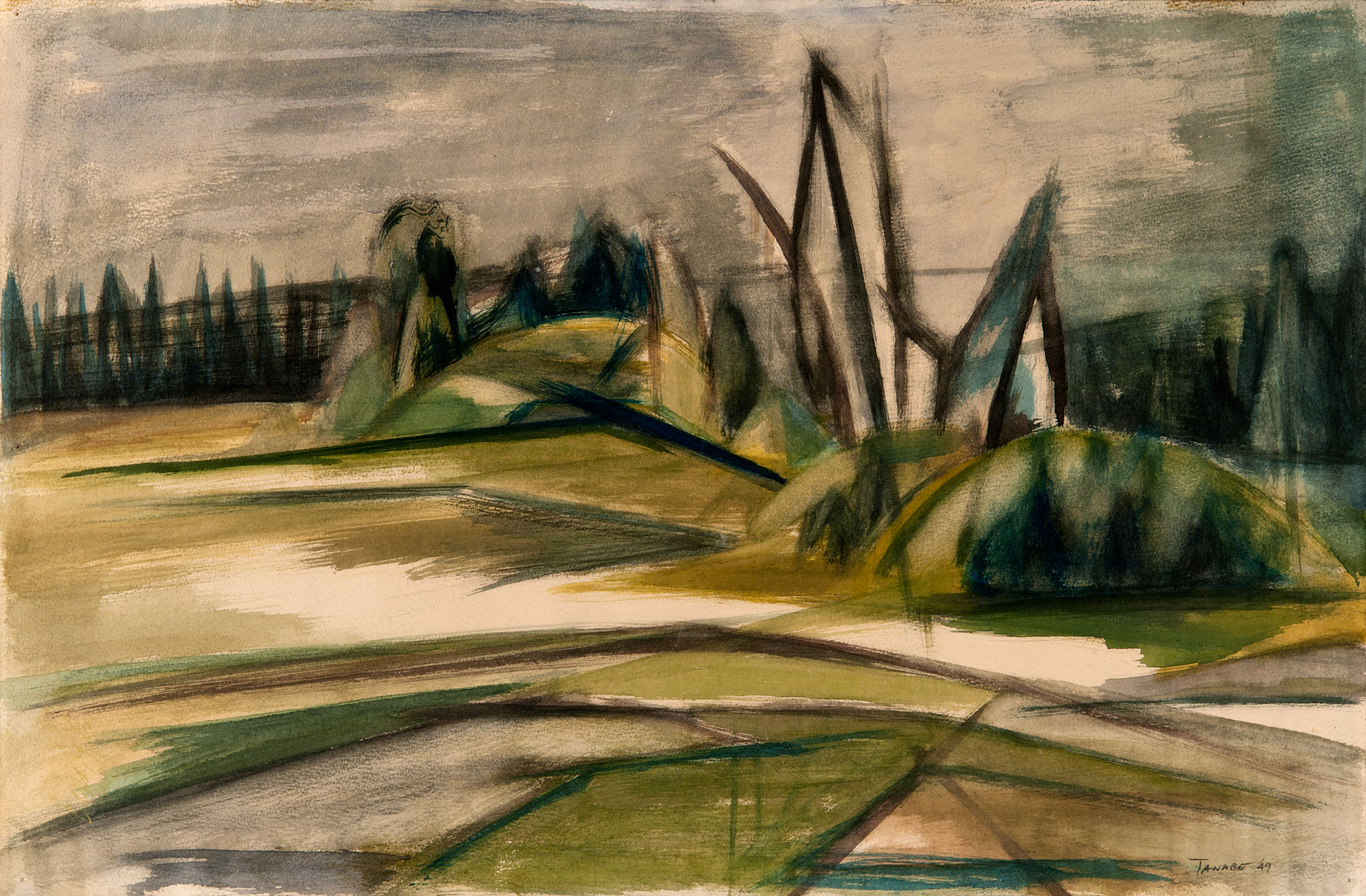

Tanabe graduated from the Winnipeg School of Art in 1949, and that summer heralded a series of key moments in his early career as an artist. First, he mounted a solo exhibition at the Hudson’s Bay store in Winnipeg (though sadly there is no record of what was shown). Tanabe and a few fellow graduates, including artist Don Roy, then set up a short-lived summer art school in Gimli, Manitoba. Primarily intended to be a money-making endeavour, the school focused on instructing students in the fundamentals of landscape painting. For Tanabe, it provided an early introduction to the demands of art education; he soon realized that teaching was not his natural forte.

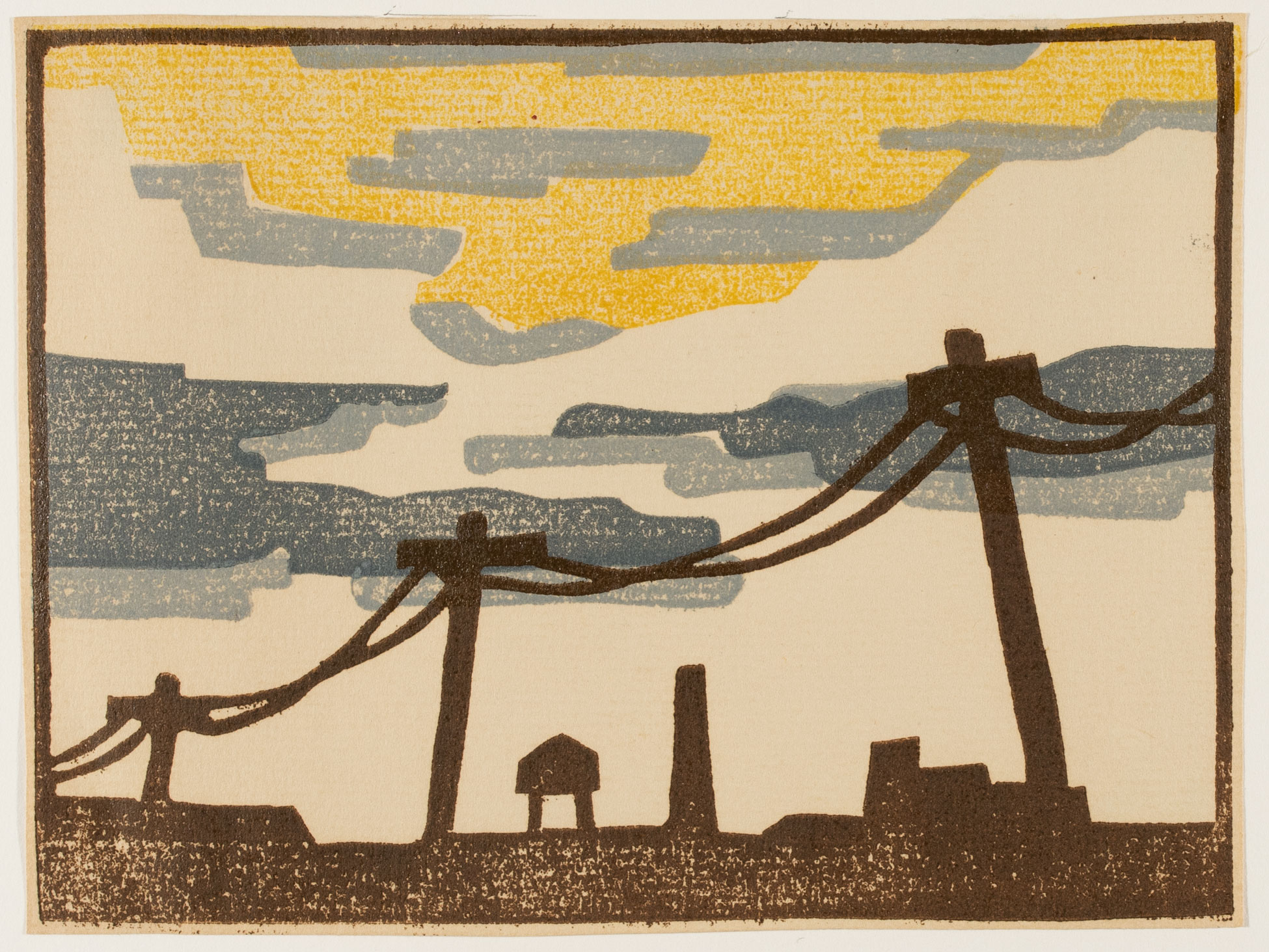

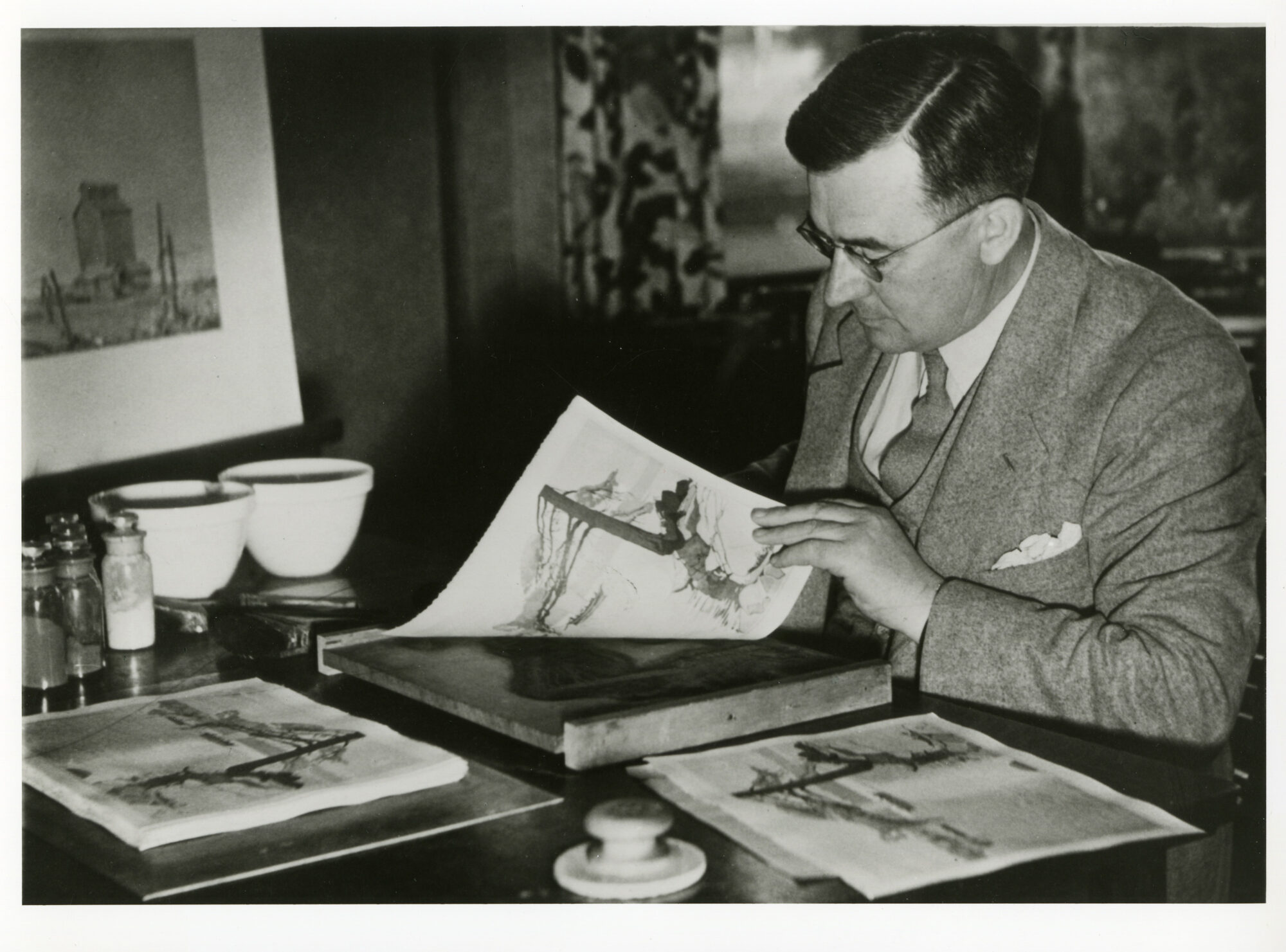

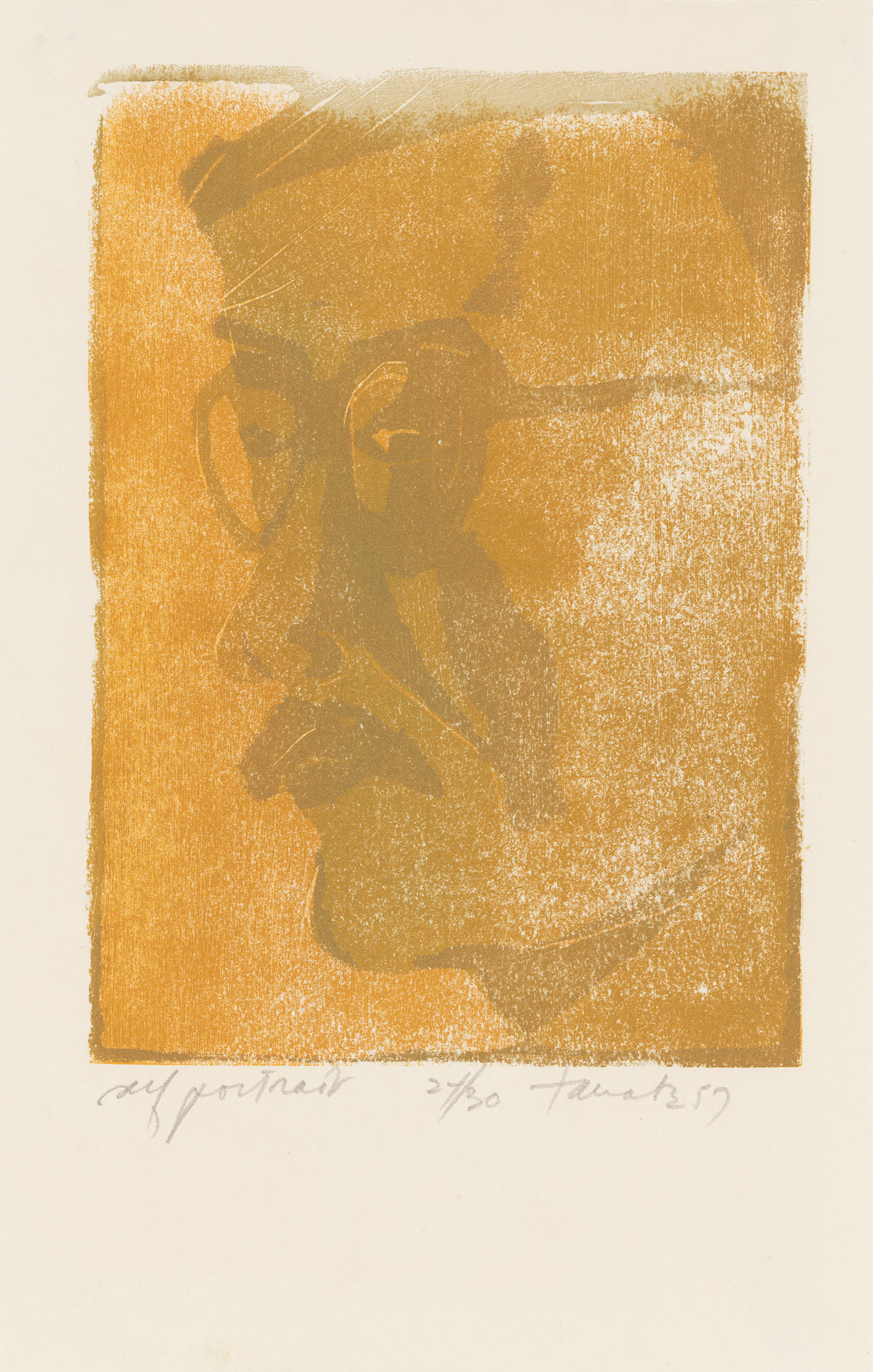

Even so, after he left Gimli, Tanabe spent the summers between 1950 and 1954 in Banff because he had heard that jobs might be available at the Banff School of Fine Arts (now the Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity). Tanabe took a job not as a teacher but as a handyman, and he had a fortuitous meeting with the artist Walter J. Phillips (1884–1963). Although their encounter was brief, Phillips invited Tanabe to his studio and showed him how to make a woodblock print. After pulling an image, Phillips gave it to Tanabe, and it remains in the artist’s collection to this day. Tanabe would later develop his own distinguished printmaking practice, working primarily with master printmaker Masato Arikushi (b.1947).

Travels and Launching a Career in Art

Following his graduation from the Winnipeg School of Art in 1949, Tanabe gave himself five years to make it as an artist. Inspired by the enthusiasm of Joseph (Joe) Plaskett and with the encouragement of his friend and teacher John Kacere (1920–1999), Tanabe decided to go to New York in 1951. Prompted by Plaskett’s endorsement, he was eager to study with Hans Hofmann, but was dismayed to discover all the painting classes were full. He settled for evening drawing lessons at the Hans Hofmann School of Fine Arts and daytime classes at the Brooklyn Museum Art School, working with the American landscape painter Reuben Tam (1916–1991).

In the early 1950s, New York was exhilarating. Tanabe absorbed emerging trends in abstraction and produced works like Fragment 41, 1951, a canvas resembling a grid-like structure composed with overlapping rectangular slabs of colour. During his year in the city, Tanabe befriended American artist Paul Brach (1924–2007) and his wife, Canadian-born artist Miriam (Mimi) Schapiro (1923–2015). Brach took Tanabe to the Cedar Tavern in Greenwich Village, a hangout for many prominent Abstract Expressionist painters and Beat Generation writers and poets. At the tavern he encountered notable artists, such as Philip Guston (1913–1980) and Ad Reinhardt (1913–1967), and listened to them talk and argue. While in New York, Tanabe supported himself by working at odd jobs, but by 1952 he was back in British Columbia.

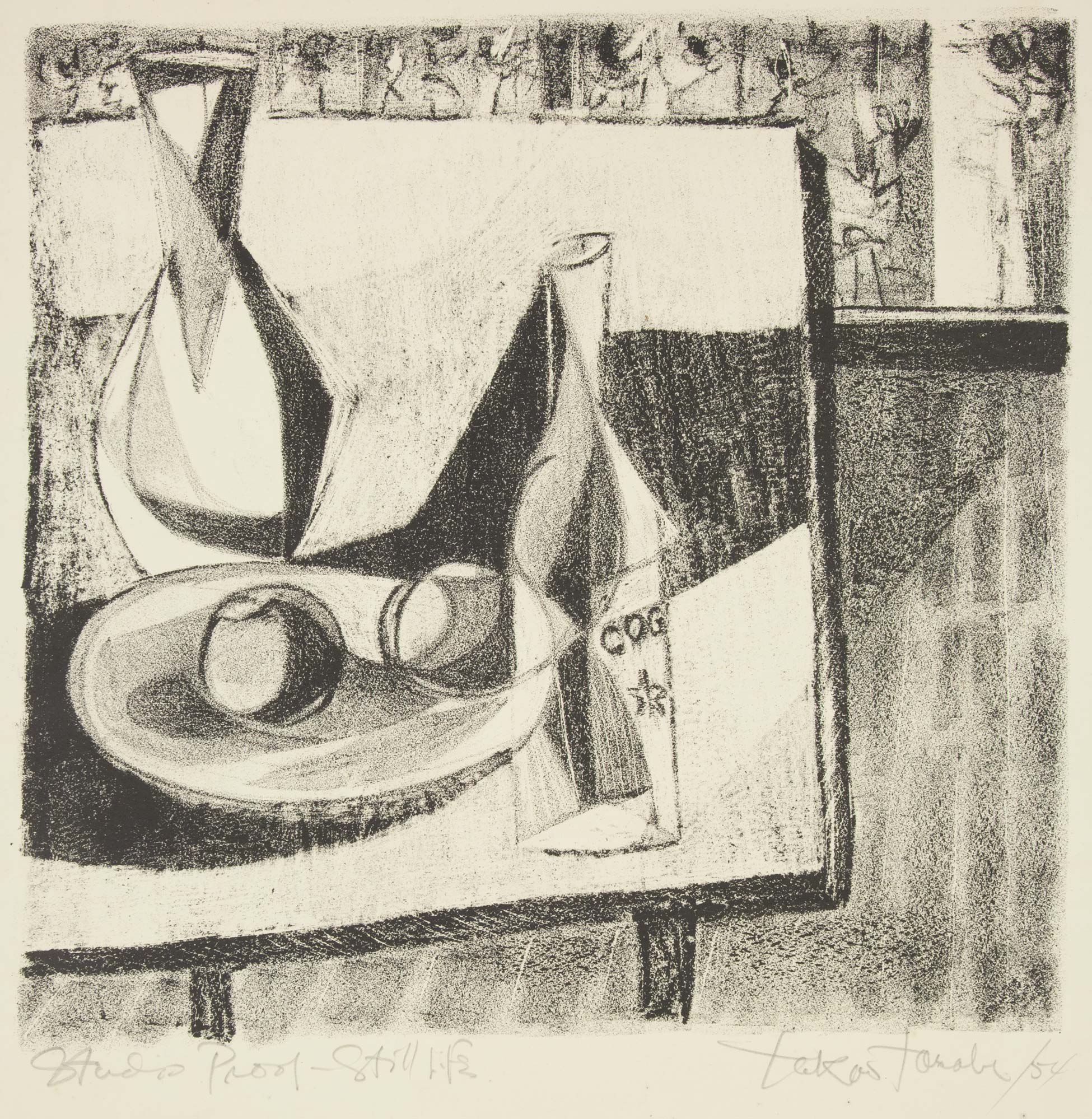

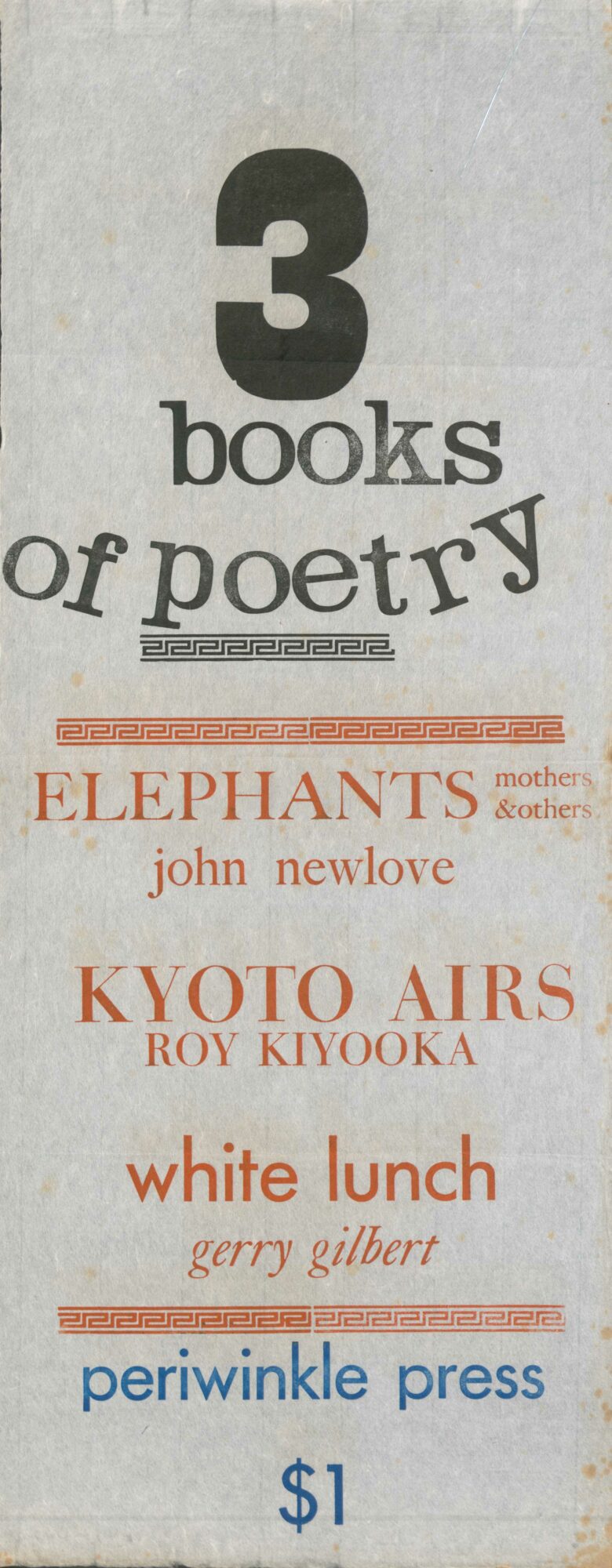

In Vancouver, Tanabe took up mural painting, and he completed his first commissioned work—titled The World We Live In—for the University of British Columbia Art Gallery (now the Belkin Gallery) in 1953. By chance, the artist also encountered his old teacher, Joe Plaskett, who introduced Tanabe to the printer and graphic designer Robert Reid (1927–2022). Through Reid, Tanabe discovered the world of printing and graphic design, and soon after the two met, they began working together. Tanabe’s fascination with printing and book design led him to form his Periwinkle Press in 1953, through which he published a series of poetry chapbooks and broadsides, bookmarks, and, later, postcards of his work. But even as he supported himself by producing beautifully designed announcements and ephemera through the print business, Tanabe continued to paint.

Tanabe’s painting efforts did not go unnoticed. In 1953, he received a telephone call from Group of Seven member Lawren S. Harris (1885–1970)—one of the trustees of the Emily Carr Estate—informing him that he had been awarded an Emily Carr Scholarship. This grant allowed him to travel to England, where he enrolled in the Central School of Arts and Crafts in London and created Study for a Landscape, 1955, the first in what would become a long series of paintings dubbed by Joe Plaskett as Tanabe’s “White Paintings.” Tanabe’s sojourn in England led to further travels in Denmark (where his friend Don Roy was living at the time), Sweden, Italy, Spain, and Greece.

On his return voyage to North America in 1955, Tanabe met educator Patricia Anne White (1925–2017). They were married the following year, eventually settling in Vancouver. Tanabe resumed working as a printer while continuing to paint and became more involved in the Vancouver arts community. After a successful one-man show at the Vancouver Art Gallery in 1957, he was invited to submit a proposal for the Canadian pavilion at the 1958 World’s Fair in Belgium (Brussels International Exhibition). Tanabe’s vision, Study for Mural for Brussels World’s Fair, 1958, showcases the painting style he was beginning to develop, with bold strokes of colour on a white ground. Like the Brussels mural, his works from this time in Vancouver often blurred the lines between abstract and figurative paintings, as in Nude Landscape I, 1959, and between abstract and landscape paintings, as in Interior Arrangement with Red Hills, 1957.

In 1959, Tanabe received a Canada Council grant and used it to visit Japan for the first time. As he has explained, “the whole war and after-war experience of being considered a foreigner in what I thought was my own country… it was time I found out whether I really was Japanese or not.” Interested in learning calligraphy and sumi-e, Tanabe enrolled in classes at the Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music. There he studied with Ikuo Hirayama (1930–2009), a respected educator and artist working in Nihonga, or modern “Japanese style” painting, and received private calligraphy lessons from Yanagida Taiun (1902–1990). Tanabe produced many works on paper, including Hillside (Tokyo), 1960, which involved techniques that helped him develop his quick, precise signature style. Tanabe’s time in Japan culminated with a solo exhibition in Tokyo at the Nihonbashi Gallery in 1960.

The Return to Vancouver and New York

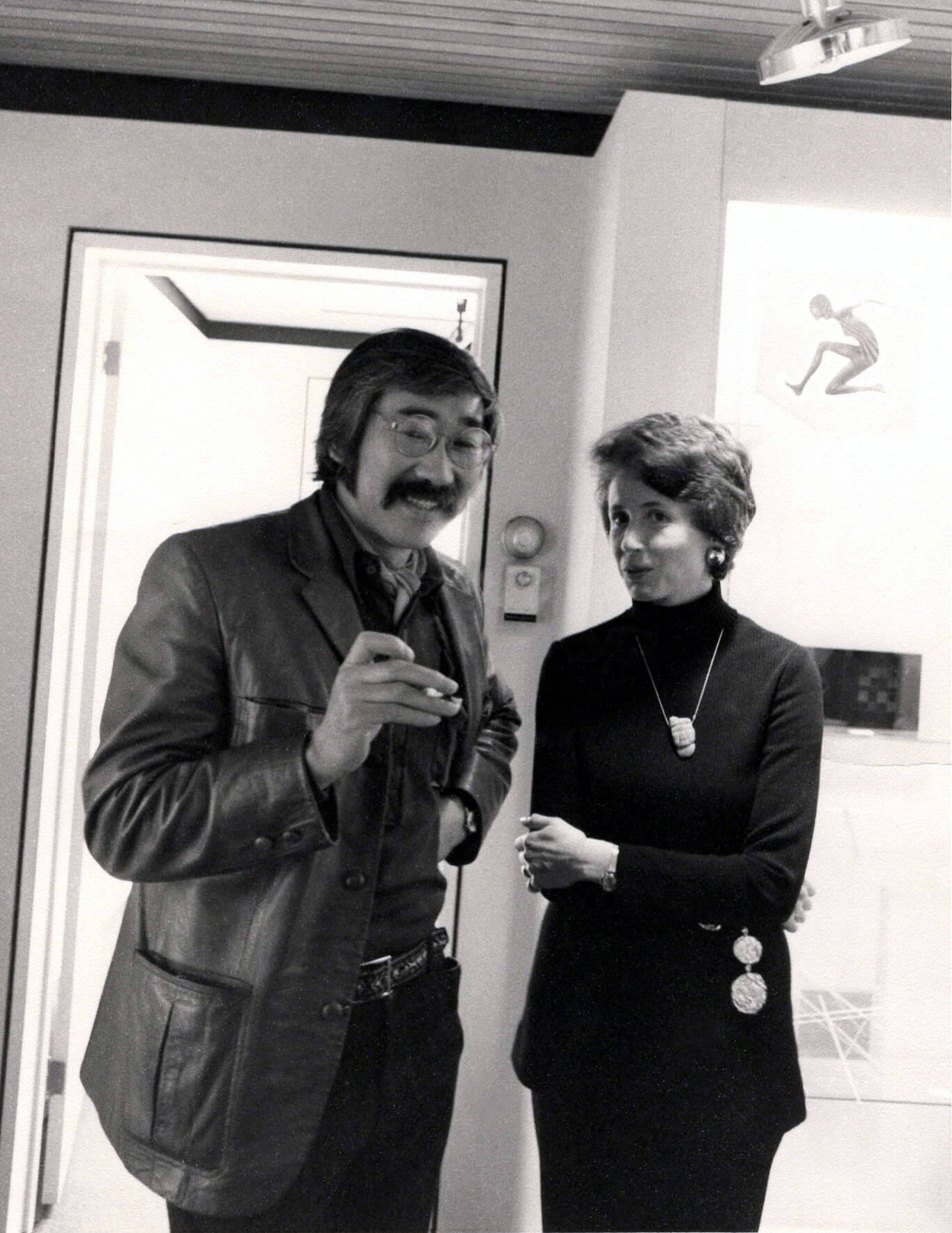

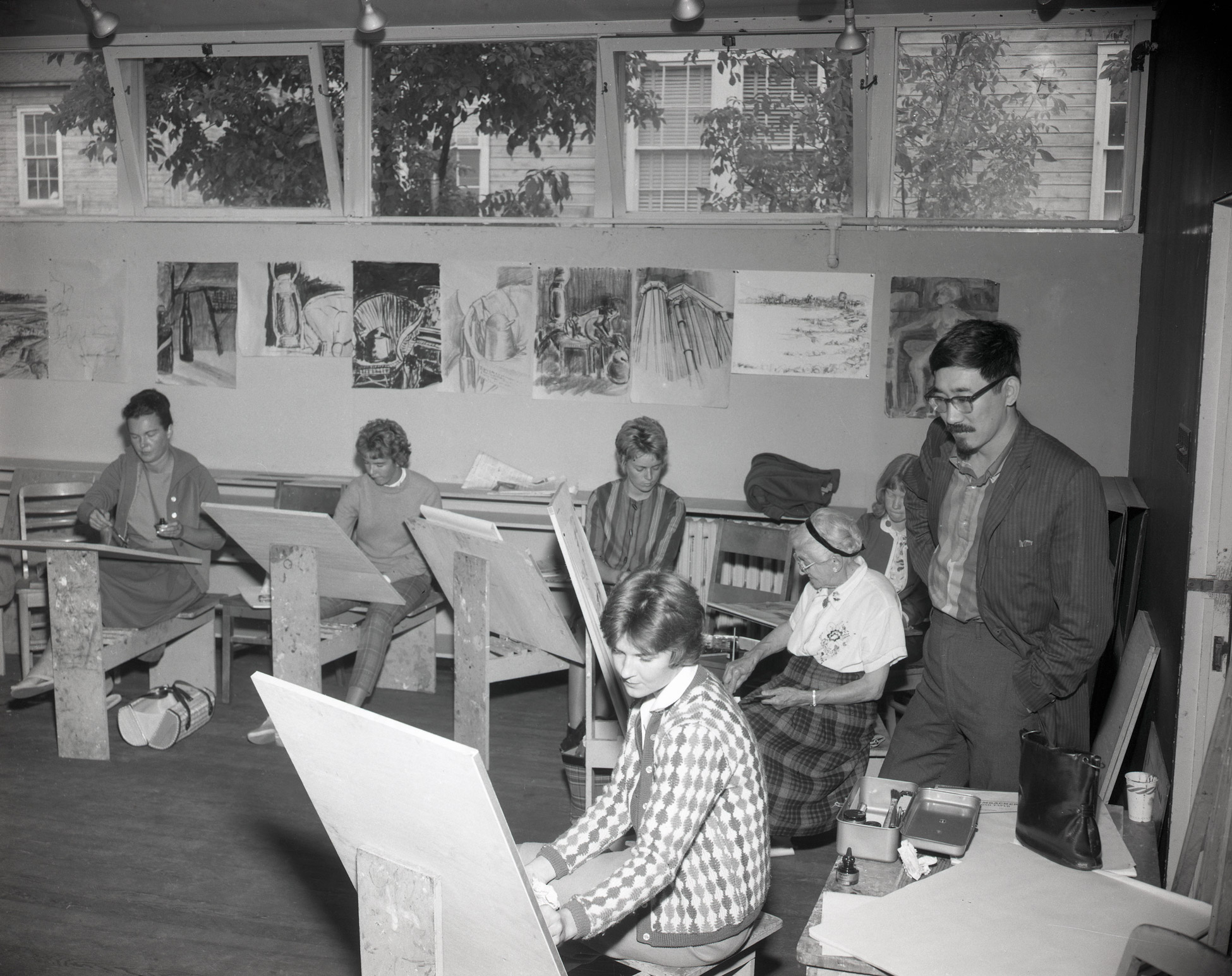

Tanabe returned to Vancouver from Japan in 1961 and once again began working with Robert Reid. The following year he built a house in West Vancouver, designed by his architect friend Peter Baker (1924–2009). To save money, Tanabe did much of the building himself, drawing on skills that he had first developed during his internment in Lemon Creek. He began teaching part-time at the Vancouver School of Art (now the Emily Carr University of Art + Design), eventually receiving an offer for full-time work at the school as the Head of the Commercial Art Department. Along with teaching and working with Periwinkle Press, Tanabe produced abstract paintings, creating both large-scale works on canvas like One Orange Strip, 1964, and small-scale works on paper like Marsh, Magenta, 1964, that each mark a notable transition away from the Abstract Expressionist influences he had absorbed during his time in New York. During this period, Tanabe also began his association with gallerist Mira Godard (1928–2010), first in Montreal and later in Toronto and Calgary.

Tanabe had a wide circle of artistic friends and contacts. Perhaps the most celebrated artist in Tanabe’s circle was Iljuwas Bill Reid (1920–1998), whom Tanabe met in Vancouver in the early 1960s. The two men got on well and Tanabe eventually became fascinated with the Haida aesthetic that Reid was refining during this period. Their friendship prompted Reid to create a wire-sculpture portrait of Tanabe. Reid’s example also encouraged Tanabe to try his hand at carving and, under Reid’s guidance, Tanabe produced a small totem pole, a mask, and several soapberry spoons.

Although Tanabe seemed well-positioned and had gained considerable respect in the Canadian art world, he was uneasy, feeling that his life was too settled, too predictable. This is despite an extraordinary episode in 1964, when he showed a series of paintings at the New Design Gallery in Vancouver. Among these works was Emperor, Spring Night, 1964, an abstract and vaguely suggestive oil and graphite painting evoking the form of the bollards situated at the dockyards on Burrard Inlet. A couple complained that the exhibition was obscene and local police contemplated charges against Tanabe. However, this did not undermine his public reputation, and he received another commission to produce an eighty-foot paper collage mural for the Department of Agriculture’s Sir John Carling Building in Ottawa in 1966. (This was followed by a set of three-storey-high silk banners commissioned by the Centennial Concert Hall in Winnipeg in 1967; nylon banners for the universities of Alberta and Regina in 1973; and a group of five eighteen-foot banners for the Canadian Embassy in Mexico City in 1980.)

Although life in Vancouver was stable, Tanabe was keen to move elsewhere. Patricia, his wife, had decided that she wanted to pursue academic studies in the United States, and so, in 1968, the couple moved to Bryn Mawr near Philadelphia so she could attend university. Tanabe quickly realized that he wanted to live in New York and found a studio that he began renovating. To earn extra money, Tanabe helped fellow artists convert their lofts into studio spaces, leaning upon the skills he had developed while working as a handyman in Banff. While he continued to commute to Philadelphia to be with Patricia, Tanabe’s creative energy was focused in New York.

The next four years were a period of great activity for Tanabe. His work was in tune with the prevailing trends of abstraction, as can be seen in his hard-edge paintings like Skeena #2, 1970. According to Tanabe, the hard-edge paintings were a complete reaction against Abstract Expressionism: “It was hard, after twenty years of doing the Hofmann thing to realize I could do whatever I wanted, as complicated as I wanted, as irrational as I wanted.” He continued to work odd jobs in order to supplement his art income, but, in 1971, Mira Godard came to visit him in New York and offered to pay him a small monthly stipend in return for exclusive rights to his paintings. This financial assistance provided significant additional support and the opportunity for Tanabe to focus on his painting.

New Opportunities in Banff

In 1972, Tanabe’s wife, Patricia, accepted a teaching position in Halifax, but he realized that the community would not provide the type of artistic stimulus he required. That same year he was offered a summer teaching position at the Banff School of Fine Arts, and he hitchhiked across the country to take up his post. Although Tanabe did not regard himself as a teacher, others—notably the painters William Townsend (1909–1973) and Gordon Smith (1919–2020) and the critic David Silcox—felt that Tanabe was the ideal candidate to run the art program in Banff. He quickly accepted the position of Head of the Painting Division and Artist-in-Residence but then tried to turn down the job later that summer when it became clear that his inclusion in a 1972 exhibition at Mira Godard’s Toronto gallery was a great success. Happily for the program in Banff, Tanabe was held to his contract and took up the position in 1973.

When Tanabe arrived, the program at Banff was a six-week summer course run by H.G. Glyde (1906–1998). Along with the summer course, Tanabe instituted a winter program focused on painting and printmaking that allowed students to prepare for a Bachelor of Fine Arts program elsewhere. His primary goal was to professionalize the program and he did so by improving the level of teaching and bringing in new people to instruct professional-level artists. He recruited staff, including Roy Kiyooka (1926–1994) and IAIN BAXTER& (b.1936), and students through extensive travels across the country. Although he was in charge, Tanabe had only a single class to teach, and the position came with a studio for his exclusive use the year round. The downside of this move to Banff was that it underlined the deterioration of his marriage. Patricia and Takao separated in 1976 and divorced in 1983.

Though Banff is surrounded by exceptional mountain scenery, Tanabe didn’t address his immediate surroundings in his work despite hiking regularly in the area, organizing weekly hikes for the students and faculty during the summer, and cross-country skiing and ice-fishing on the Bow River in the winter. Instead, this time in Banff saw Tanabe produce a long series of prairie landscape paintings that were celebrated in the Norman MacKenzie Art Gallery’s touring exhibition, Takao Tanabe, 1972–1976: The Land.

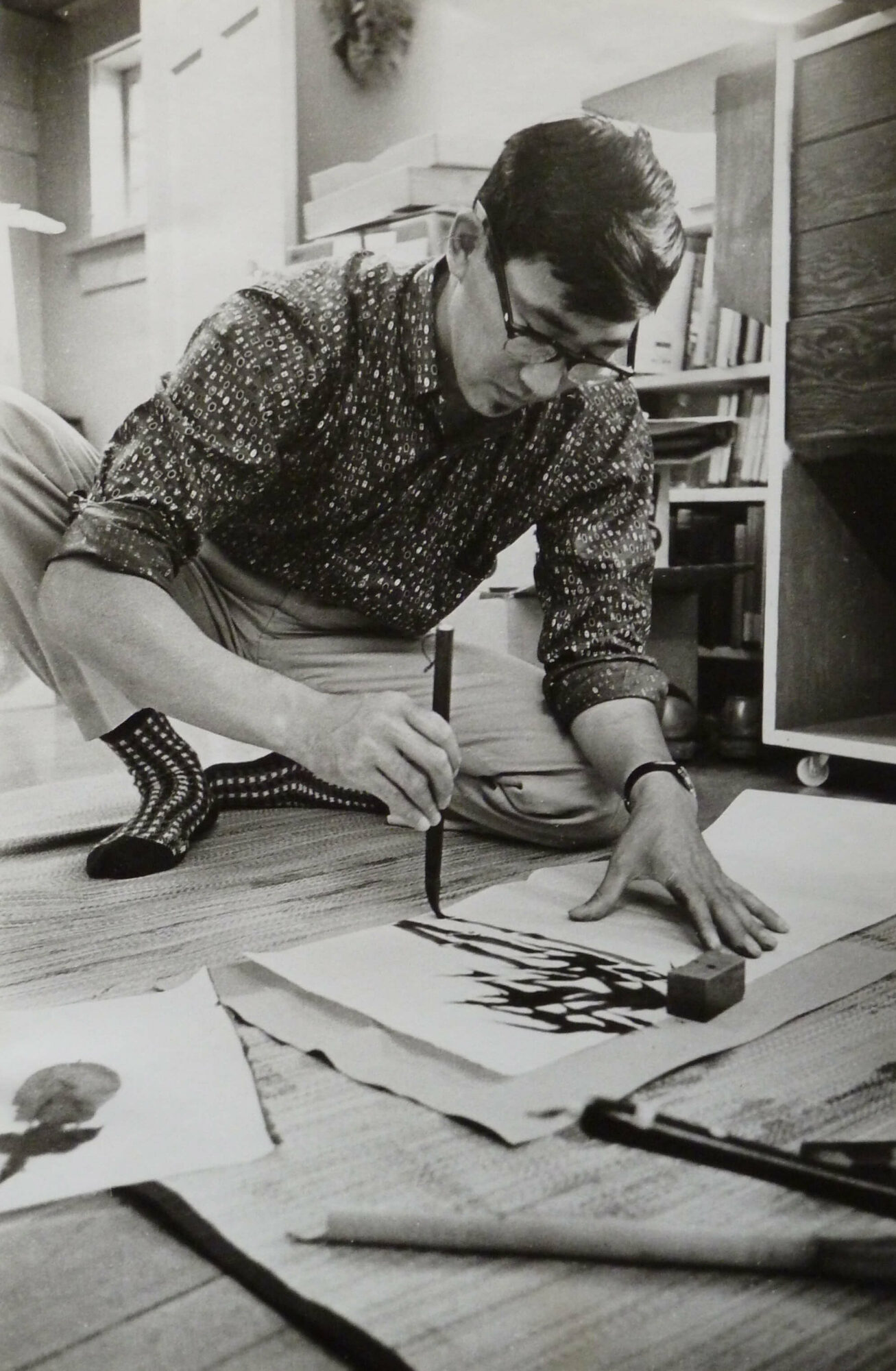

Tanabe saw the prairie in a manner unlike any previous painter. Using acrylic paint, Tanabe produced visions of enormous prairie skies, rolling fields, and the foothills of the Rockies without reference to human intervention. Works like The Land 31/75, 1974, The Land 4/75 – East of Calgary, 1975, and The Land 22/77, 1977, illustrate the maturation of Tanabe’s characteristic “one-shot” painting technique that he had developed while learning calligraphy and sumi-e in Japan. The prairie paintings produced in Banff, and indeed most of Tanabe’s works since 1970, were executed with the canvas stretched across a flat surface in a manner similar to how a calligrapher works, rather than upright on an easel. This allowed Tanabe to thin his paint considerably and to apply it in quick, sweeping strokes. In Tanabe’s own words, “I want the paint to be put on [the canvas] as though it just arrives without visible brush marks. So the surfaces are, generally speaking, quite flat.” Stripping both his subject matter and his materials to their bare essentials, Tanabe wanted the composition to seem as if it had simply appeared from the ether. This seeming effortlessness belied the amount of work and planning involved in every composition.

While in Banff, Tanabe was fiercely supportive of his students and staff and sought to better the lives of artists across the country. In addition to substantially upgrading the quality of teaching at the Banff School of Fine Arts, Tanabe’s leadership at the school also saw the inauguration of the Walter Phillips Gallery in 1976. As a member of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts (RCA)—Tanabe was elected an Academician in 1973—he lobbied the organization in 1978 to protest the removal by ministerial order of a public artwork by John Cullen Nugent (1921–2014) from the front of the Canadian Grain Commission building in Winnipeg. Nugent had a won a commission to produce No. 1 Northern, 1976, but the abstract steel sculpture proved unpopular and was cut up and removed in 1978. When the organization failed to act, Tanabe resigned from the RCA in 1979 and, with several friends, formed the Marquis of Lorne Society as an alternative.

The West Coast Beckons

Although Tanabe had taken a sabbatical in 1977, by 1980 he thought that he had accomplished what he could in Banff and felt the need for a change of location and painting subject. He had also met Anona Thorne (b.1948) in the mountain community and started a relationship with her. For Tanabe, it was a time for a new beginning.

Tanabe has said, “I was born on the coast and feel most at home here.” He had considered returning to British Columbia since 1978 and was looking for property on Vancouver Island. A visit with an old friend, the artist and designer Rudy Kovach (1929–2006), led to the purchase of an acreage near Parksville. Here Tanabe built a house and studio, at once remote yet close enough to Vancouver for easy commuting into the city.

Although Tanabe never advertised himself as such, he had experience in building, and he had helped several artists convert their lofts into workable studio and living spaces. This experience served him well when it came to building his home on Vancouver Island, which he largely constructed himself. As he said, “I built a big studio with a small living area.” Although the property is not on the coast, water is important for Tanabe, and so he had a large pond excavated behind the house and studio. In 1982, Anona Thorne moved to B.C. to join Tanabe, and together they divided their time between an apartment in Vancouver and the acreage on Vancouver Island.

The move back to the West Coast meant a dramatic shift in Tanabe’s subject matter and a return to the natural world of his childhood. The lack of administrative and teaching duties and the ability to devote himself exclusively to his painting led to a substantial increase in his output. The paintings for which he is most renowned—the majestic, misty canvases of West Coast shores and islands such as Barkley Sound 1/93: in Imperial Eagle Channel, 1993—soon emerged from his new studio home.

Throughout the more than four decades that Tanabe has lived on Vancouver Island, he has developed his style away from the “one-shot” paintings that had characterized his work of the prairies to more detailed studies of the landscape. However, conceptual links to the prairie paintings remain, especially in the artist’s desire to make his misty, rain-obscured vistas appear effortless despite the tremendous amount of labour necessary to produce them. Like his prairie paintings, these coastal works are devoid of human presence, substantially detailed, rendered with thin applications of paint, and often require months of work to complete. In his works based on photographs such as the diptych Low Tide 5/89 Rathtrevor, 1989, and Strait of Georgia 1/90: Raza Pass, 1990, Tanabe pares away what he regards as extraneous detail to get at the essence of his subject matter.

Tanabe’s life in B.C. is characterized by a rich artistic production and the creation and nurturing of an idyllic semi-rural retreat, a cherished home for both Tanabe and Thorne. He maintains contact with the world, but a certain isolation is important to his artistic process.

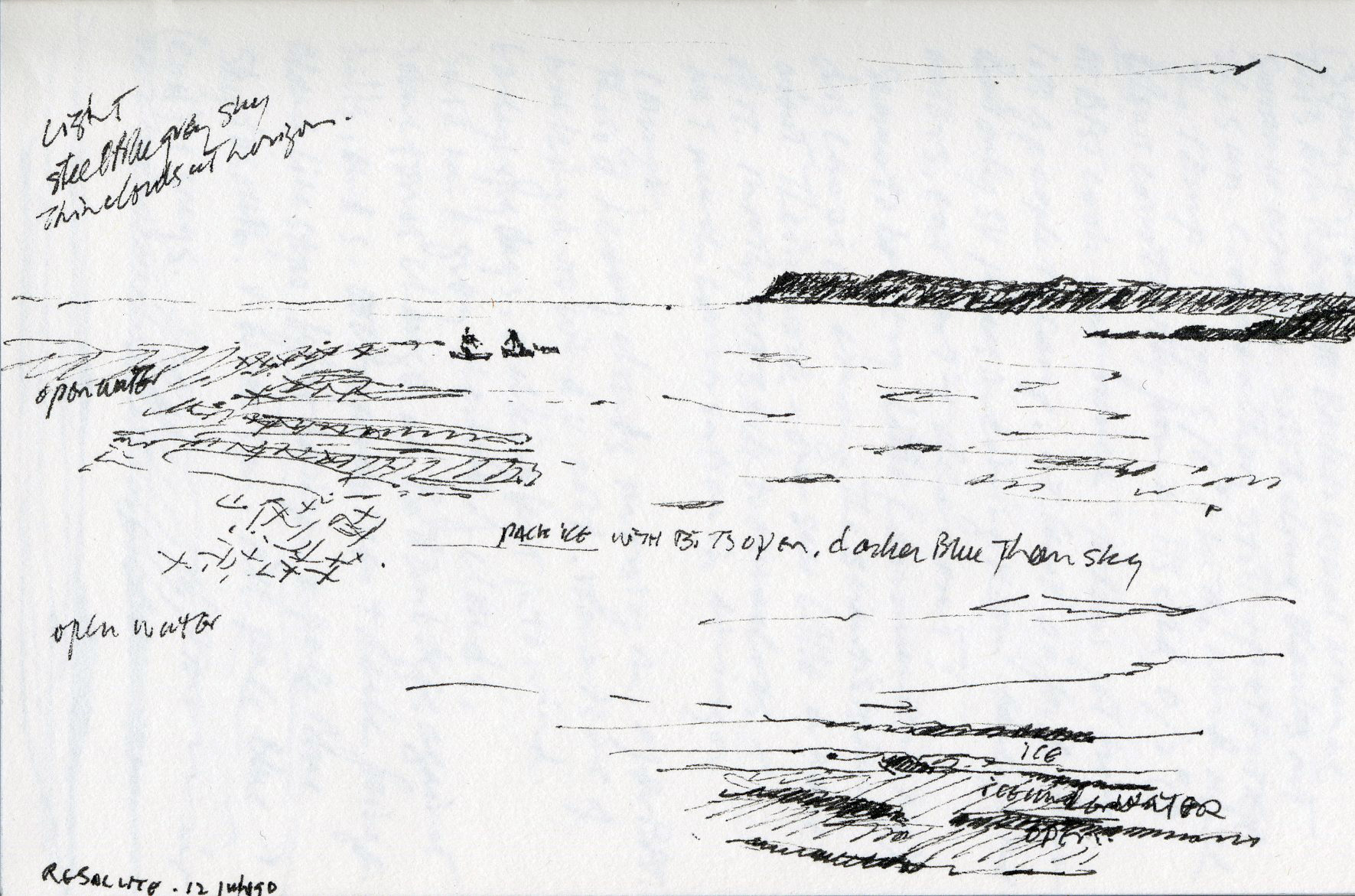

Lack of a formal education turned Tanabe into an autodidact, and he educated himself through extensive reading and, perhaps more importantly, his travels. Together and separately, Tanabe and Thorne have visited Europe, Japan, Peru, India, and Australia, to name just a few destinations, and Tanabe has travelled extensively in Canada. Sometimes these trips, which Tanabe documents with photographs, lead to new works, such as High Arctic 1/90, 1990, and Tunisia 1/96: Near Nefta, 1996. Education is the key motivation for his travels. Tanabe is constantly looking at art, architecture, and the landscape—the latter, wherever it might be, often providing the spark for a work of art.

Legacy, Community, Generosity

Tanabe’s work is widely admired and collected, and his contributions have been recognized by some of Canada’s leading institutions and top prizes. Tanabe has received three honorary doctorates—from the University of Lethbridge (1995), the Emily Carr University of Art + Design (2000), and Vancouver Island University (2014). He received the Order of British Columbia in 1993, the Order of Canada in 1999, a Governor General’s Award in Visual and Media Arts in 2003, the Paul D. Fleck Fellowship at the Banff Centre in 2007, and the Audain Prize for Lifetime Achievement in the Visual Arts in 2013. Although these awards are appreciated, his focus is on the art itself. As Tanabe recently commented, “It is about the painting.”

Since moving to B.C., Tanabe continues to exhibit widely and has had dealers and regular exhibitions in Vancouver, Toronto, and Calgary. In 2005, Tanabe was the subject of a retrospective, organized jointly by the Vancouver Art Gallery and the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, which travelled to Vancouver, Victoria, Halifax, and Kleinburg. This retrospective was a revelation to most viewers because few were familiar with the breadth of Tanabe’s work as both an abstract and landscape painter. A second retrospective featuring his works on paper, Chronicles of Form and Place: Works on Paper by Takao Tanabe, was organized and circulated by the Burnaby Art Gallery and McMaster Museum of Art in 2011.

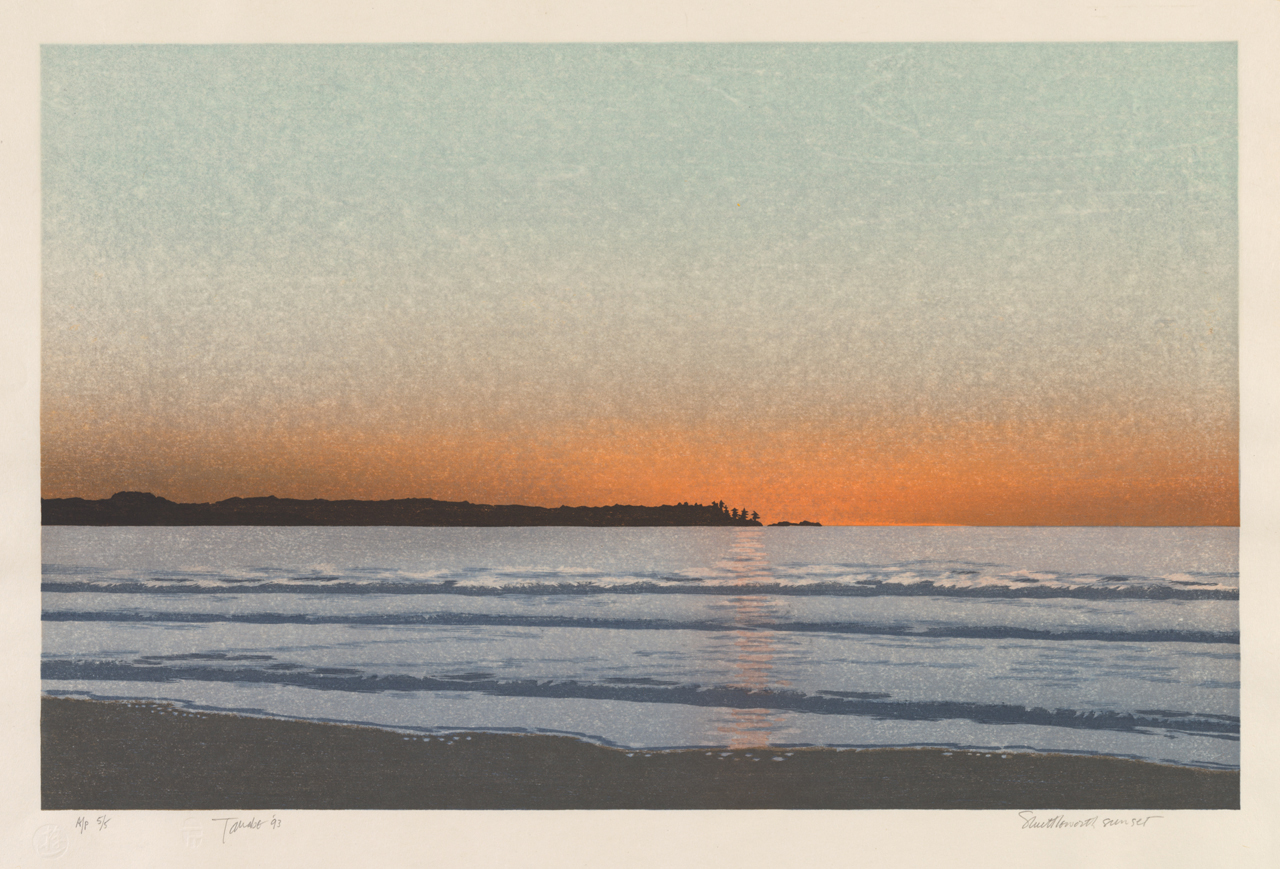

As his success has grown, Tanabe has given back to the art community prodigiously and continues to believe in the importance of the voice of the individual artist. Beginning in the 1990s, Tanabe hosted a series of painting retreats for himself and younger artists, organizing expeditions to Shuttleworth Bight (at the northern end of Vancouver Island) and to Boat Basin (near Tofino and the site of the garden of Cougar Annie). Two Vancouver artists who went on those trips were Landon Mackenzie (b.1954) and Renée Van Halm (b.1949). Mackenzie has noted that at Shuttleworth Bight, “Tak’s mighty generosity was in full force along with his experience with food, wine, boats, tides, crabbing and sea fishing.” Mackenzie also remarked upon Tanabe’s social support of the younger generation through gatherings including artists, writers, and curators that he hosted at his Vancouver apartment, which she described as “really special and intergenerational.” He would extend this goodwill to students, bringing books and materials to local schools and studios.

Similarly, Van Halm is appreciative of Tanabe’s friendship and support. She recalled one of the trips she made with Tanabe and a group of other artists and critics to Shuttleworth Bight in 1993: “Tak and some buddies had built a fishing lodge up there. There was nothing there [except] the house, a rustic west coast modern they had built in the middle of nowhere, accessible only by boat from Port Hardy. It wasn’t so much a residency as a retreat; most of us didn’t do any artwork. It was mostly social with lots of hiking in an area Tak knew well and long talks over meals.”

Overall, Tanabe was keen to provide the opportunity for artists—most of whom worked in ways that were dramatically different from his own practice—to associate and socialize and, if appropriate, to produce artwork. Believing that the visual arts were under-recognized within Canadian culture, Tanabe campaigned for more than five years to secure the establishment of the Governor General’s Awards in Visual and Media Arts. This involved extensive lobbying of politicians and possible donors across Canada. These efforts were finally successful when the award was established in 1999, with the first laureates in 2000 including art historian and curator Doris Shadbolt (1918–2003), and artist Michael Snow (1928–2023). As noted, Tanabe was honoured in 2003. More recent recipients include Rita Letendre (1928–2021) in 2010, Robert Houle (b.1947) in 2015, and Ken Lum (b.1956) in 2020.

In 2016, he established the Tanabe Prize to be awarded to outstanding emerging painters based in British Columbia. This $15,000 annual prize is awarded by a jury of artists and is administered through the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria. In 2022, Robert Burke (b.1944) and Rain Cabana-Boucher were the recipients. In 2018, the Takao Tanabe Purchase Prize in Painting for Young Artists was established at the National Gallery of Canada (NGC). The $15,000 annual prize enables the NGC to acquire a work by an emerging artist—a significant early career achievement. That year, works by lessLIE (b.1973) and Cynthia Girard-Renard (b.1969) entered the NGC collection.

Tanabe has also provided scholarships for young artists at OCAD University, NSCAD University, the University of Manitoba, the Emily Carr University of Art + Design, Simon Fraser University, the University of British Columbia, and the University of Victoria, in addition to some scholarships in other disciplines, and he donates widely to arts organizations. Supplementing these more public gifts, Tanabe has, over the years, regularly purchased the work of younger artists and donated it to museums.

Tanabe continues to advocate on behalf of artists, expand his philanthropy, garden his acreage on Vancouver Island, and, above all, paint. Despite some eye problems that have troubled him since his late eighties, he produces canvases of immense sensitivity and beauty. He does what he feels he needs to do as an artist, with little thought to the market or critical reception. This sterling integrity in pursuit of his artistic goals is the distinguishing characteristic of his more than seventy-year career. As he noted in 2009, “If you are painting a landscape, you are a dinosaur. But I don’t let it stop me from painting the kind of painting I want to paint.“

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements