Lake’s oeuvre suggests a lifelong preoccupation with a number of key themes—society, gender, and universal experiences of power and authority—which she explores through a blend of performance, photography, and photographic manipulation. Her art-based activism began during the civil rights movement in Detroit and continued after she moved to Montreal and then to Toronto. Starting in 1970, Lake began putting herself into her art, embracing her body as a site for her art, influencing other artists—her contemporaries, as well as younger generations, through innovations in her approach and in her teaching—to do the same.

Identity and the Self

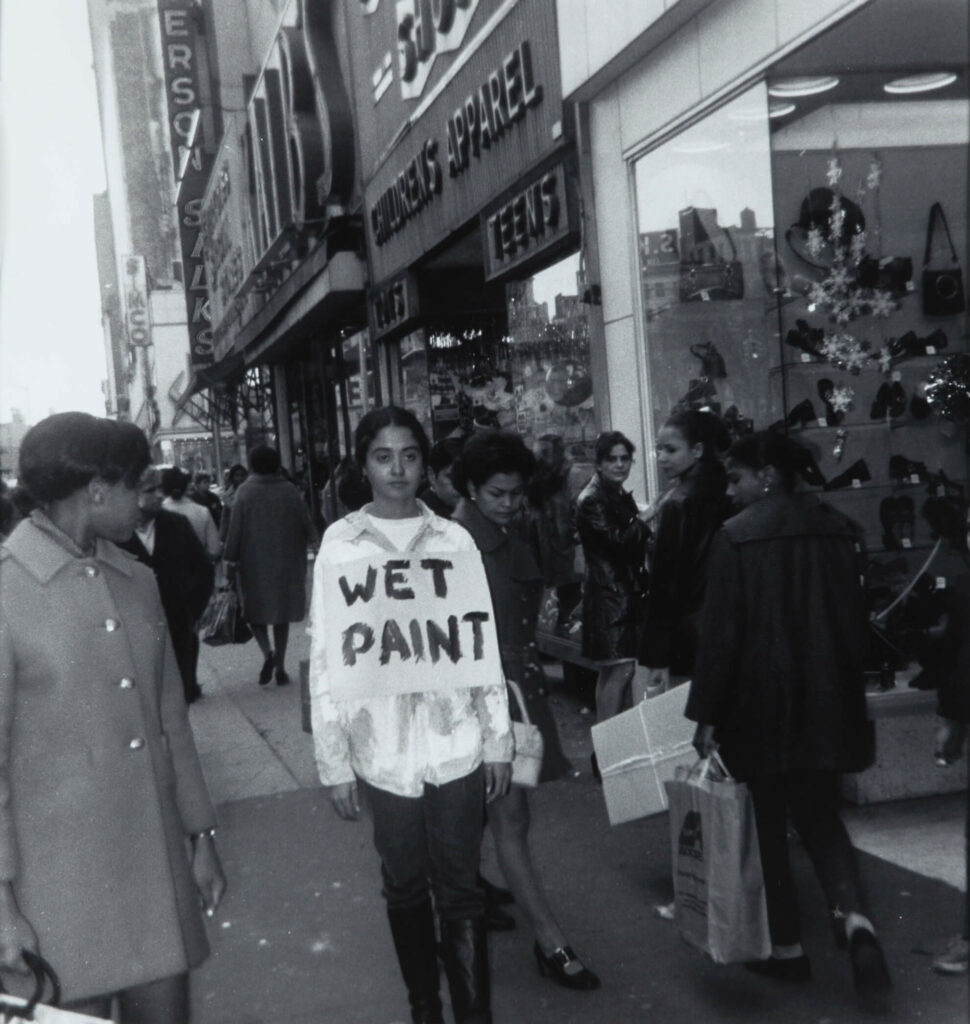

Through her own experience with the civil rights and anti-war movements in Detroit, Lake became interested in exploring the identity of her generation. In the early 1970s she was exposed to feminist artists including Adrian Piper (b.1948), Nancy Spero (1926–2009), and Martha Wilson (b.1947), who were also studying subjectivity and identity formation and the possibilities afforded by the photographic medium for these investigations. In Piper’s Catalysis, 1970–73, for instance, the artist photo-documented herself performing a series of attention-grabbing gestures in public spaces. While in some of the images, the individuals with whom she is sharing public space seem oblivious to her actions and presence, in others, they appear to have their heads turned to look at her, suggesting that in these scenarios, Piper’s presence was heightened by her actions, catalyzing a consideration of her difference as someone standing out from the crowd. An early activist and feminist, Spero focused many of her painted and collaged works through the 1970s on representations of women amid the backdrop of global political struggles. The series Torture of Women, 1976, for example, included accounts of women’s experience of torture with paintings of female figures. Wilson, with whom Lake would eventually be exhibited, is also known for photographic work exploring identity and female subjectivity via role-playing—for instance, in the series A Portfolio of Models—The Working Girl, 1974.

Through photographic portraiture, Lake examined issues of identity in works such as On Stage, 1972–74, that, paired with an interest in role-playing, formed the basis for an early relationship between performance and photography. In this series, Lake performed for the camera, and the resulting photographs served a double function as artwork in themselves and as a documentation of the performance. In 1973 she took up the camera to produce Imitations of the Self, one of the first of her works to consider how identity is formed within the self and in relation to society, reflecting her lifelong preoccupation with forms of civic awareness and engagement.

Identity is a constant source of interrogation for Lake: in the “masking” in her whiteface photo-performances from the early 1970s (Miss Chatelaine, 1973; Imitations of Myself #1, 1973/2012; A Genuine Simulation Of…, 1973/1974); in the transformation of the self in Suzy Lake as Gary William Smith, 1973–74; or in the submission of the self to others in Choreographed Puppets, 1976–77. From the 1970s to the early 1980s Lake figured centrally in her own work, not to convey a biographical sketch but to excavate a more general “self” in relation to society as well as “the self” as a construct. As she said, “I don’t try to say what my identity is. I’m not some heroine recounting my life. I needed a constant, a vulnerable subject for a reference point. The reason I use myself as a model is because I’m always on hand, always around.”

Nevertheless, Lake’s broader concern was for the self in relation to society. Mass media had made images and products associated with self-fashioning ubiquitous, often directing advertising at women consumers through beauty magazines, and these provided fertile terrain for Lake. Her work from the 1970s—notably, her fascination with media, framing, and perception—anticipates the movement that, late in the decade, came to be known as the “Pictures” generation. This group of artists was interested in representational imagery and mass media. Curator and art historian Douglas Crimp was the first to attempt to identify their new technique and style in his 1977 exhibition Pictures, where, he noted, they created works by exploring “processes of quotation, excerptation, framing, and staging.” For example, the genre-defining work of American artist Barbara Kruger (b.1945) produced biting commentary on the objectification and subjugation of women, and the role of images in these processes, through her use of bold typeface and appropriation of photographic images borrowed from mass media and art historical plates.

It is notable that during the 1980s Lake ceased to appear as a subject in her work in order to focus her lens on specific political struggles. The absence of explicit representation of “her” self as a stand-in for “the” self reaffirms the centrality of Lake’s enduring preoccupation and engagement with the world around her, as well as her desire to innovate appropriate representational strategies toward the concerns in question at any given time. This absence is significant in particular with regard to the political issues of pressing concern to Lake through the 1980s: the struggles of the Teme-Augama Anishnabai of Bear Island and the Sandinista National Liberation Front, among them. Moving outside the broader social struggles she directly encountered and participated in as a white North American woman required her to move away from attempting to represent struggles beyond her experience through using herself as model.

In 1994, after a decade spent in political activism, Lake returned to depicting herself with the series My Friend Told Me I Carried Too Many Stones, 1994–95, and Re-Reading Recovery, 1994–99, at this time also recognizing the experience of the aging body and the older woman as a site to explore. “Experience is positive; maturity is positive,” she said, “but our culture doesn’t celebrate these attributes when associated with aging.” In remarkable series from these years, Lake exaggerates the stereotypes of aging (Peonies and the Lido, 2000–2006, playing off the melodramatic depictions of death and aging by Dirk Bogarde in the 1971 film adaptation of Thomas Mann’s 1912 novella Death in Venice); magnifies the nuance and nuisance of continuing to role-play femininity in mainstream society (Beauty at a Proper Distance, 2000–2008); and defies the societal expectations placed on older women in society (Forever Young, 2000).

The photographic self-portraiture of Lake and her contemporaries has been viewed by many commentators as anticipating the advent, in the 2010s, of “selfie culture,” the vernacular practice of taking photographs of oneself using smartphone cameras, often resulting in the circulation of these images on social media platforms such as Instagram. However, the selfie is usually intended to suggest a spontaneous approach to self-portraiture, which differs from Lake’s practice in that her images and process are slow, representing her preoccupation with time and process. Although Lake is invested in media and social perception, she engages with popular media as a critique rather than an exaltation. The selfie is vernacular, unskilled; Lake’s work is technically masterful. The selfie is about “my” self; Lake’s work is about “the” self.

Activism

The activist seeds underlying Lake’s practice were planted at a young age as she witnessed and participated in the social upheavals in Detroit in the 1960s, particularly the civil rights movement. This early political consciousness would follow Lake through her career as she discovered and innovated visual strategies for translating “what was happening in the streets” into art. One of her earliest events, Annual Feast, 1969–72, in which she invited other artists and cultural workers into her studio, mirrored the gatherings known as “Happenings” that were bringing groups together.

The role of art in political activism hit a fever pitch in the 1960s and early 1970s, when art became political for many artists, especially in the way they responded to the ongoing Vietnam War. They were enraged by America’s role in the war and by American art institutions, such as the Museum of Modern Art in New York, that received major funding and support from benefactors who supported President Richard Nixon’s policy on the Vietnam War. The German-born artist Hans Haacke (b.1936) became an early proponent of Institutional Critique and, with his artwork MoMA Poll, 1970, waged a direct confrontation with Nelson Rockefeller, the chair of the MoMA board.

In 1969–71, Lake shared the same goals as the New York–based Art Workers’ Coalition (AWC), an open coalition of artists and cultural workers who employed artistic means to advocate for museum reform (particularly the fair representation of women artists and artists of colour) and for museums to take a moral stance against the war.

Around the same time, feminist artist Martha Rosler (b.1943) created her series House Beautiful: Bringing the War Home, c.1967–72—photocollage works juxtaposing the domestic imagery found in home and lifestyle magazines with brutal journalistic imagery from Vietnam combat. These works continued in the tradition of photomontage artists such as Hannah Höch (1889–1978) and John Heartfield (1891–1968), who used similar agitprop strategies in contesting the Second World War. The advent of mass media technologies and their incorporation into artworks in the early twentieth century extended the political allegorical work of eighteenth-century painters such as Francisco Goya (1746–1828) and Jacques-Louis David (1748–1825), as well as the anti-war Cubist paintings by Pablo Picasso (1881–1973), who incorporated mass media forms into his canvases.

In contrast to more strident artists, Lake’s strategy was subtle rather than instructive; she resisted and challenged authority through metaphors in her art. Some of the major themes Lake explored include control and resistance, endurance, and the formation of identity. Though rooted in her personal culture and gender, they extend to broader social meanings. For Choreographed Puppets, 1976–77, Lake engaged her entire body, yet she ceded control of her movement to two “puppeteers” overhead who, while standing on the scaffold she had built, manipulated her arms, legs, and torso with straps tied to her body. The photographs of this performance, which another assistant took at regular intervals, depict the blur of her movement and her consequent loss of identity. In staging, performing, and recording this contradictory relationship between control and submission, Lake produced a visual accompaniment to a universal experience. As William Ewing observes, “Viewing the piece through the long lens, it becomes clear that the work addresses the manipulation and powerlessness every human being must feel, at least sometimes, as a member of the collaborative collectivity.”

Lake has also used concepts and ideas to allegorically stand in for broader issues of power in other works. In imPOSITIONS, 1977, the images of her struggling against coercion ask the viewer to reflect on the power and authority one person can exert over another. Late in life she continues to employ allegory to provide commentary on political struggle. In her series Game Theory: Global Gamesmanship, 2019, for instance, she appears on a broken marble chessboard, mimicking the poses of the queen and the pawns in an exploration of the collateral damage of politics and war.

In the 1980s Lake turned away from the subtler political gestures of earlier work that focused on her own body and entered a more overt activist phase. It was around the same time that fellow Torontonians Carole Condé (b.1940) and Karl Beveridge (b.1945) returned to Toronto from New York, abandoning an apolitical form of Conceptual art and establishing practices as political artists engaged in processes of consultation and collaboration with labour and community movements. Their series Oshawa, A History of CAW Local 222, 1982–83, combined staged photographic images and personal testimony of working conditions and unionization attempts at the General Motors plant in Oshawa, Ontario, in the period following the Second World War, when married women were permitted to enter into factory work—one part in a series of works devoted to the history of the Canadian Auto Workers (CAW) Local 222.

Lake’s work from this time might be thought of similarly: through her friendship with the Teme-Augama Anishnabai of Bear Island, she agreed to produce the series Authority Is an Attribute … part 2, 1991, as a form of visual advocacy for their land claim. In this collaborative installation she juxtaposed life-sized photographs of Band members standing before locations of special meaning to them with cut-outs of authority figures holding binoculars and businessmen “game players” playing chess. By emphasizing the importance of specific places for Indigenous peoples, Lake drew attention to historical colonial injustices toward Indigenous peoples as well as the urgent need to rectify them today. A trip to Nicaragua in 1985 to support the Sandinista National Liberation Front further emphasizes her political commitments of the period, both instances demonstrating Lake’s constant adaptation of her approach to image-making alongside political engagement to respond to the specific conditions, preoccupations, and urgencies of her subject matter.

The Body and Place

Along with Carolee Schneemann (1939–2019) and Yoko Ono (b.1933), Lake was considered an early practitioner of body art. This art form became associated, in the early 1970s, with feminist art by Ana Mendieta (1948–1985), Hannah Wilke (1940–1993), Adrian Piper (b.1948), and others. For Lake, the body—her own body—became a medium in itself, open to the same types of manipulations and distortions that she experimented with in her photographs. In her work, the separation between the body and the photograph is intended to narrow to the point where one cannot exist without the other.

While living in Montreal, Lake met several avant-garde artists, many of whom were known for Minimalist artworks. In contrast to the stark objectivity they followed, she adapted their adherence to mastering a medium’s qualities into her own style—one that allowed for the expression of human emotion. On this issue, she was also influenced by postmodern dance—an emerging style of dance whose development she was aware of and following.

In the early 1960s, artists and dancers associated with the Judson Dance Theater in New York, including Robert Morris (1931–2018), Simone Forti (b.1935), and Yvonne Rainer (b.1934), enacted a series of encounters between human bodies and a variety of inanimate objects in loosely scripted yet unpredictable ways. As Lake explains, “I clearly appreciated the Judson Dance Theatre because of their progressive form and content; but I was mostly excited by them because they included duration and the body.” Dancers associated with Judson emphasized non-classical, everyday movement—a major departure from classical and modern dance tenets—often using duration and repetition as a mode through which to closely examine the concept of movement itself. Although these experiments influenced Lake, the camera became her invisible yet ever-present companion—a recorder through which she permitted her own concept of art to emerge.

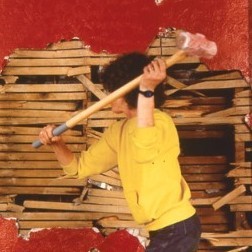

Vertical Pull #1, 1977, explores and documents how the body responds to and resists authority and control. Rather than think about her body as flattened into the two-dimensional plane of the photograph, Lake saw the image as a space to occupy and break out of, as in Pre-Resolution: Using the Ordinances at Hand, 1983–85, where she demolishes the drywall in her house with a sledgehammer. Made up of twelve images arranged in a grid of three columns of four, Vertical Pull #1 appears to reconstitute a set of stairs, broken up by the edges of the photograph and repeating three times in three columns. Lake, who is bound, kneeling, or lying on the steps at a lower register with each successive row, appears to descend the stairs, her body blurred by her movement. The photographic depiction of movement evokes the earlier experimentations of postmodern dancers and the documentation of their performances, as well as their encounters and negotiations with the constraints and possibilities of the built environment. In Lake’s series, the steps become a support for Lake’s body—a type of stage or plinth that performatively complicates her liberation and visually restrains her body within the spaces between the steps. In the image, the steps appear as flattened horizonal lines into which Lake’s body fits snugly.

In the early 2000s Lake returned to her body to explore issues related to beauty, aging, and the place of the older woman in a society obsessed with youth. Her photographic work magnifies the signs of aging, with a clinical view of wrinkles, facial hair, and skin blemishes (Beauty at a Proper Distance / In Song, 2001–2), as well as in more theatrical tableaux, such as Peonies and the Lido, 2000–2006. In contrast to early explorations where she applied whiteface and cosmetic makeup directly to her face or her photographs (Miss Chatelaine, 1973), these later works magnify the made-up face in an almost clinical manner. More recently, Lake has performed fashion again, but here as an older woman using fashion-show conventions. In Performing Haute Couture, 2014, the geometries and architecture of the garments themselves are manipulated and amplified by Lake’s poses. The “constant” is Lake’s own body, and through this consistency viewers are permitted a long view of the kinetic, biological, and social shifts that the body endures over time.

Change is critical to Lake’s Transformations series. For this work, Lake has stated that she chose the subjects because she had “learned something” from them—so she found it appropriate to morph into them. In the case of Françoise Sullivan (b.1923), this Montreal-based Automatiste artist and dancer had already created a kind of conceptual template to Lake’s own interest in relating the body to its location and documenting the body in motion. In 1947—the year of Lake’s birth—Sullivan embarked on her cycle of dance solos dedicated to the seasons. Completing only the summer (L’été, 1947) and winter (Danse dans la neige, 1948) cycles, she intended the performances to be presented as a complete work, and had individuals, including artists Françoise Riopelle (b.1927), Jean Paul Riopelle (1923–2002), and Maurice Perron (1924–1999), as well as her mother, film and photograph her dancing. Sullivan’s performance was groundbreaking both in her move outside the dance studio into the natural environment and in her desire that the performance be viewed not in real time, but as documentation. This desire is reflected in Lake’s own practice as well.

In many of her works, Lake considers the importance of in-between spaces to her exploration of the self, as in Passageways, 1982, and Bridge, 1982–83. These two constructions combine wooden structures with photography in such a way that the images of the body are fragmented by the grids. Passageways appears as two wooden structures suggestive of the scaffolding behind a finished wall but positioned parallel to each another so they create a corridor. The scaffolding doubles as a hallway and a gallery, with a series of squares and rectangles of empty and filled space producing the feeling of a salon-style gallery hang. Lake’s body is perceptually reconstituted through the inclusion of life-sized cut-up images of herself, depicting a foot, a leg, a torso, and a head, spread out across columns. In these works, Lake is reliant on the confining structure in order to come into view as a subject. In contrast, in Pre-Resolution: Using the Ordinances at Hand, 1983–85, the space becomes a place to break out from.

Extended Breathing in Public Places, 2011–14, an extension of the original Extended Breathing series, 2008–14, might be seen as exemplary of Lake’s concern with place because the series began in her own backyard (Extended Breathing in the Garden, 2008–10), suggesting a personal relationship to her domestic surroundings. However, a second iteration includes photographs of Lake in public places such as the Detroit Institute of Art and the post–September 11 World Trade Center in New York City, images that carry their own political significance in terms of endurance. As such, they become a mirror of the artist’s fortitude. Lake’s presence in front of these sites associates her with a living social history.

Performing an Archive, 2014–16, a series that depicts Lake in the process of photographing the various houses in Detroit that belonged to her ancestors, also provides a longer view in which to document urban and suburban histories. Many works in the series have a left-hand column with a small photograph at the top and, below, a Detroit 1896 historical real estate plan of the neighbourhood, along with a larger image on the right of Lake photographing the site. Just below the top left of each photograph, she provides photo-album-like information about the significance of the place to her family. Her presence lends a biographical reading to the series, while her body—always a standard of measurement—provides an entry point, a specific vantage point, and a broader concept of place.

In her preoccupation with place, Lake shares interests with other photographers, including the Chicana-American artist Laura Aguilar (1959–2018) and the Ottawa-based artist of Plains Cree / European descent Meryl McMaster (b.1988), both of whom situate their own bodies in relation to natural landscapes of personal significance and social identity. Aguilar sought to locate the lives of LGBTQ+ people of colour in the natural and built landscape and, therefore, as part of the cultural imaginary community around notions of “place.” Her Nature Self-Portrait #2, 1996, shows the artist, curled up nude and facing away from the camera, appearing to be in the desert. The sense of her body as object is accentuated by its position among four boulders. This juxtaposition in turn leads to a sense of life within the static objects, rendering both the animate and the inanimate as part of the natural environment.

Gender/Feminism

Lake is considered a pioneering feminist artist, one of a handful of women artists such as Carolee Schneemann (1939–2019), Lisa Steele (b.1947), Hannah Wilke (1940–1993), Joan Jonas (b.1936), Adrian Piper (b.1948), and Eleanor Antin (b.1935) who used their own bodies in their work to explore issues related not only to power but to power as inevitably gendered. She did not, however, consider her work to be feminist until later in her career:

In terms of talking about identity, except at the very beginning, I always felt I was addressing an audience that was not female only … Because I am female, gender was inclusive. On specific points, I realized that people were hearing something different than what the work was saying because of the body … I began to understand why it was so necessary for women to talk to women … so you could actually hear what their reception was of the work, rather than just the reception … of a male audience. So that was a big thing that really allowed me to say, “Yes, I am a feminist artist.” I hope my audience is broader than that, but I’m not backing off that.

Before the convergence of rights movements in the late 1960s, proto-feminist artists had begun to employ their own bodies within their work, with many of the prominent works to emerge from Fluxus and in underground cinema being reclaimed as feminist work in later decades. American artist Carolee Schneemann is considered one of the most notable examples of the belated recognition of the significance of the body as medium to the development of feminist art. However, at the time in which she was producing her early works, such as the photo-performance Eye Body: 36 Transformative Actions for Camera, 1963, in which the artist produced thirty-six photographs in an environment she created that included broken mirrors, mannequins, and tarps, her own body unclothed and covered in grease, chalk, and plastic, she was regularly accused of creating pornographic work and, on many occasions, censored for dealing with taboo subjects such as women’s sexuality and eroticism.

Lake did not explicitly identify with the feminist cause in her early work. But by virtue of her choice to figure consistently as the subject of study, her work has been regarded as contributing to an emerging feminist art aesthetic. However, Lake’s art is different from the explicitly feminist works of her time, such as the “central core” imagery, which concentrated on the vagina as a site of power. Through the Flower, 1973, by Judy Chicago (b.1939), is, perhaps, the best-known example of this art. Lake’s performances, examinations of the gendered body, and embodied experience of the world have, nevertheless, lent her work a feminist reading.

Given the political undercurrents of the early 1970s, the mere presence of a woman’s body meant it was read as implicitly “female” and, therefore, as feminist. The adoption of specific formal and conceptual strategies—such as performance, the body, staging, and the use of photography and video—by significant women artists including Antin and Piper also led people to consider Lake as a feminist conceptual photographer. Both Antin and Piper engaged with the body in their works. Antin’s iconic Carving: A Traditional Sculpture, 1972, in which the artist documented herself between July 15 and August 21, 1972, as she reduced her food intake, producing four images every day (front, back, and both profiles), explores the conventions of traditional sculpture and attempts to conform to its classical ideals. Lake has identified Piper’s The Mythic Being, 1973–75, as a strong influence: in this photo series, Piper performed as a racially and gender ambiguous character and collaged these images with excerpts from her diary, exploring racial dynamics and notions of the self in relation to society.

Within the context of women’s liberation, anti-war protests, and civil rights in both the United States and Canada in the 1960s and 1970s, Lake’s exploration of identity and authority encouraged critics to read her work as feminist, even if only metaphorically so. As Martha Hanna writes, “Although she has not overtly addressed feminist issues, the politics of feminism is an undercurrent in all her major photographic works to date [2008]. The attention to power relations that feminism implies may be seen in Lake’s work as symbolic of a personal struggle, and her artwork is evident of her progress.”

In her later work on beauty and aging, Lake has explored the gendered elements of embodiment, experience, and perception more closely. In particular, she examined the social conventions of femininity. The Extended Good-bye #2, 2008–9, from the series Extended Breathing, 2008–14, asks the viewer to reflect on questions of when the aging body becomes invisible in society. Similarly, Thin Green Line, 2001, from the series Beauty at a Proper Distance, 2000–2008, interrogates what the appropriate grooming conventions for older women should be.

Through her blending of performance and photography in her art, enhanced by her early won skills in painting, drawing, and printmaking, Lake has, over fifty years, made a provocative contribution to many of the significant issues for her generation—issues of identity in relation to society, gender, and the universal experiences of power and authority.

Ahead of Her Time

The title of Lake’s retrospective at the Art Gallery of Ontario, Introducing Suzy Lake, offered a playful commentary on the fact that Lake, although she had been working as an artist since the 1960s and had long been considered influential to artists familiar with her work, was becoming known to new audiences only in the 2010s. As curator Georgiana Uhlyarik has explained about the exhibition’s title: “It works on the level that a lot of people don’t know her work and this is going to be their first introduction—she never really had a show at this scale, or her full career—but for us, the core of her work has to do with performance and in particular the performance of the self and the way in which the self keeps navigating and introducing and reintroducing itself as it navigates societal forces … And this ongoing act of introducing herself, introducing this idea of Suzy Lake again and again over her career.”

Her approach to photo-performance, as distinct from photographing a performance, would go on to influence Cindy Sherman (b.1954), who has regularly cited her as an influence. Lake has often been exhibited with contemporaries, including Eleanor Antin, Lynn Hershman Leeson (b.1941), and Martha Wilson (b.1947), artists viewed as complementary in their approaches or themes. She has also been included in pivotal survey exhibitions devoted to feminist art, including WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution (curated by Connie Butler, touring 2007–2008) and WOMAN: The Feminist Avant-Garde of the 1970s, Works from the Sammlung Verbund (Vienna) (touring 2013–18).

The 2010 touring exhibition Traffic: Conceptual Art in Canada, 1965–1980 (curated by Grant Arnold, Catherine Crowston, Barbara Fischer, and Michèle Thériault, with Vincent Bonin and Jayne Wark) attempted to organize the flurry of Conceptual art activity happening across the country in the wake of Canadians’ embrace of contemporary art, the advent of new communications technologies, and the influence of American social and cultural trends. Photography and video art figured prominently, with Lake’s participation in the Montreal exhibition featuring Suzy Lake as Gary William Smith, 1973–74, a large-format sequence of photographs from her Transformations series, 1973–75, in which she gradually replaces her own features with those of other people, resulting in a final photograph in which she is entirely transformed.

A younger generation of artists may be viewed as evoking many of Lake’s concerns and strategies—notably, Meryl McMaster, whose photographic work often explores issues of identity and the identity of others, and the ways by which identities are constructed through social masks. In her series Second-Self, 2010, McMaster invited individuals to draw blind-contour portraits of themselves, which she then transformed into wire sculptures that hung in front of their faces in her photographic portraits. Like Lake, she also painted her subjects’ faces white “to represent this protective social mask or persona we wear, either real or metaphorical.” The Vancouver-based artist and vocalist Carol Sawyer (b.1961) has built a three-decades-long practice of posing and performing for the camera, albeit presenting herself as her alter ego, the modernist artist Natalie Brettschneider. For Lake, self-portraits are not created to position the artist but rather as an evaluation of the human condition. Both the body and the photographic apparatus function in tandem as modes through which to enact, endure, and document these explorations.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements