Decades before the “selfie” sparked a cultural paradigm shift, Suzy Lake (b.1947) changed the course of art history, taking up her camera and using it as a tool to investigate how we manufacture the self, often using her own body as a model to investigate issues of identity, gender, beauty, and aging. Incorporating elements of theatre, performance, and role-playing, Lake blended technology and art to create works so ahead of their time it took the art world nearly two decades to catch up. As an activist, Lake has demonstrated a profound commitment to feminism and civil rights. Her artistic output spans more than forty years, and today she is recognized as one of the world’s most important image-makers.

Early Years in Detroit

Suzy Marx (later Lake) was born into a German-American working-class family on June 14, 1947, in Detroit, Michigan. Her father, Robert Marx, a Second World War veteran, was a roofer, and her mother, Helen Marx, a housewife. Robert’s ancestors had lived in the city since 1883. Lake grew up in a hard-working, conservative household on Washtenaw Avenue, in a predominantly white neighbourhood on the east side. Amid Detroit’s racial divisions and political upheaval during that decade, she was struck by the disparity of the poor working and living conditions for African-American families looking to settle in the area. She recalls, “My father had a roofing and sheet metal shop in the city … It was in a segregated neighborhood … I was aware of inequality and racism as a child, so when I was old enough to act, I joined solidarity groups.” She later became involved in the anti-war and civil rights movements of the 1960s.

Lake’s grandfather Arthur Marx was a hobby painter, and he encouraged the young Suzy’s artistic development by drawing with her and taking her to the Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA). Despite Lake’s traditional upbringing, in particular around gender roles, where women were discouraged from pursuing higher education in order to tend to domestic responsibilities, her family urged her to attend university. Having developed an interest in the visual arts as a child, one that continued through high school, she enrolled first at Western Michigan University in the College of Fine Arts in 1965 and the following year at Wayne State University, majoring in studio arts with a focus on painting and printmaking.

As a student, Lake was especially captivated by Abstract Expressionism and German Expressionism (a fascination instilled by her grandfather), absorbing whatever influences she could. At Wayne State she was inspired by instructors David Barr (1939–2015), a sculptor, and Robert Wilbert (1929–2016), a figurative painter whose design class became a foundation for Lake’s interest in formalist techniques. Her focus became the purely visual qualities of line, space, texture, shape, and presentation rather than representation or narrative content. In Contact X, 1973, for example, she arranged a configuration of thirty-six contact sheets in a grid pattern to form the photographic image of a hardwood floor with a large white X painted over it, and traced the outline of two legs with dangling feet in the top left corner. Lake’s early interest in working through questions of how we perceive an object in space is clear in this image with its focus on composition. By photographing the X she had painted and fracturing the image into parts, Lake tacitly asks the viewer to mentally assemble the image and reflect on the relationship between painting and photography and the act of seeing.

During her university studies, Lake moved to live in downtown Detroit, where the racially charged atmosphere of the city core led her to become involved with the burgeoning civil rights movement. While she was always “curious about the world,” the political struggles of the 1960s, such as the civil rights movement and its intersections with the early women’s liberation movement, inspired her, and she found she could “no longer… keep questions to [her]self.” She volunteered with the Detroit Mothers, an organization that assisted single African-American women in the Jeffries Project. She helped care for their children and taught skills such as resumé writing, so they could enter the workforce.

In July 1967 the Detroit Riot, a series of confrontations that began as a response to police brutality toward African-Americans and extended to anger over unemployment and segregated housing and schools, lasted for five days in the sweltering heat. These riots, among 159 race riots that occurred in the United States throughout that year, resulted in forty-three deaths, over a thousand injuries, multiple burned properties, and extensive looting. Canadian curator Michelle Jacques has noted that Lake’s upbringing, during which her parents instilled a strong sense of individual and community responsibility, and these summer riots were instrumental in developing Lake’s political consciousness and helped her devise strategies for working in solidarity with oppressed populations.

By this time, she was in a relationship with Roger Lake, a painter. Disillusioned with the violence in Detroit and wanting to avoid the Vietnam draft, they married in 1968 and immigrated to Canada, even though Lake had not finished her studio arts degree. She soon fell “in love” with her new city, Montreal, though, as she described, it was a shock to learn that, under Quebec’s civil code, derived from the Napoleonic Code, she was “technically [Roger’s] property!”

Montreal: A Pivotal Decade

When Lake entered the Montreal art scene in 1968, it was at a pivotal moment. Quebec was experiencing the emancipatory effects of the Quiet Revolution and, by chance, she once again found herself in the midst of political crisis and revolution. Although Lake was not pursuing a feminist activist agenda, women’s social, legal, and financial inequalities both within and outside the civil rights and anti-war movements inspired her interest in women’s liberation. At this time, before a feminist consciousness began to emerge in her work, Lake was still primarily working in painting, drawing, and printmaking—for example, Car Key Drawing, 1972; Re-Placed Landscape, 1972; and Lake Superior Via, 1973.

The early 1970s were heady times to begin exhibiting in Montreal. Expo 67 had focused international attention on the city, the Quiet Revolution was well under way, the Front de Libération du Québec (FLQ) and the October Crisis of 1970 exposed the separatist threat, and ideological struggles between anglophone and francophone feminist groups concerned with class, race, and global solidarity aligned with anti-colonial movements. Having moved from one hotbed of political activity into another, Lake absorbed elements from all these causes and incorporated them into her art.

Soon after Lake arrived in Montreal, she worked as a life model at several institutions, including the school at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (MMFA). Through this connection, she met the sculptor Hugh LeRoy (b.1939), who in turn introduced her to Guido Molinari (1933–2004). She became Molinari’s assistant, and he had a profound impact on her. Molinari was famous for paintings of hard-edged sections of colour in which the forms of the colours became his subject—the content of his art; Green-blue Bi-serial, 1967, is a typical example. Lake’s recollection is that the elastic-like quality of Molinari’s paintings, the way each colour appears to stretch into the next, suggested a shift to her—from thinking about the “action” of paint on canvas to considering the act of seeing the painting as a process that involved the viewer. As Lake recounted:

I met Guido quite soon after my undergraduate training in painting and printmaking (probably ’69 or ’70). I had strong technical and formal skills in those media. Although I knew I wanted to reflect more of what was happening in the streets, I began with reduced figurative work … I admired both [Molinari’s and LeRoy’s] work, but it took time for me to realise how they maximised their formal aspects to be perceptually performative. Molinari got very excited about juxtaposing specific colour[s] to activate the edges of his stripes[…] It was discussions with Guido about his work and the relationship of my own elements that made me gradually understand [these elements] were more active to the view than merely placement.

Lake began to translate Molinari’s exploration of the way paint is visually perceived in abstract works—a process emphasizing contrasting colours, shapes, and lines—into her own practice. She experimented with multiple techniques to achieve the results she wanted. She describes this process as “the plurality of language to orchestrate the image,” or the way language, the way we talk about an image, can change our perception of that image. Over the following years she used her education in painting and printmaking while focusing on her own body as a site of artistic expression and creating works of photographic manipulation—for example, by placing materials on the surfaces of photographs, as in A Genuine Simulation of… No. 2, 1974, in which Lake applied cosmetics directly onto the portraits. Whereas Molinari experimented with different shades and tones of paint to challenge viewers to see colours in new ways, Lake’s experiments with photographs challenged viewers by refusing any straightforward experience of seeing the subject of the image (often Lake herself).

During this period, Lake studied dance and mime at Théâtre de Quat’Sous in Montreal, where she learned the meaning of whiteface makeup—a thick white paint that she called the “zero state” that erased the performer’s personal characteristics and provided a “tabula rasa following the political and social changes of the 1960s.” Whiteface makeup had tremendous potential for turning one’s own body into a canvas for experimental art. Before long, Lake linked up with Allan Bealy (b.1951), a student at the School of Art & Design at the MMFA, as well as Tom Dean (b.1947) and other young iconoclasts who were exploring new forms and strategies of art-making different from the Minimalism and geometric abstraction that dominated the contemporary art scene in the city.

Lake began experimenting with play and performance. When she and Dean went on a picnic together, for example, they dressed as nineteenth-century painters, she as Impressionist Mary Cassatt (1844–1926) and he as Post-Impressionist Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864–1901). Lake photographed such performance events so she would later be able to go back to them in documentation form, experience them from a different perspective (as observer rather than participant), and study the shifts in information conveyed as a result of the change of medium and viewpoint; however, she did not consider these photographs to be finished works. Eventually Lake turned to performance, photography, and video as a set of tools for creating, buoyed by the freedom that artists enjoyed in Quebec as agents for change in the new emerging society. As she put it, she set out to balance “the relationship between my classical training and my work as an activist on the street.”

Forging Communities

In the late 1960s, several artists across the country, with Montreal as an important centre, were occupied with Conceptual art—artwork in which the idea was more important than the technique with which it was created. Lake began conceptual experiments in her Montreal studio with performance, drawing on the local art community to be both participants and audience. There, through this participatory studio space, she also began to use her art practice to bridge the political currents she witnessed in Quebec: “I was trying all kinds of different things to figure out how to bring content into my works, so that what was happening on the street made sense with what was happening in the studio. I was trying to figure out who I was as a result of a lot of radical social change.”

A global counterculture had been coalescing in response to the Vietnam War, civil rights struggles, women’s liberation, and various decolonization movements around the world. In North America, burgeoning hippie and protest cultures promoted an anti-conformity stance, and numerous communities experimented with alternative forms of relationships, communion, and mobilization that extended into the art world, notably through Happenings. In 1969, in the midst of this social revolution, Lake hosted her initial Annual Feast, where she silkscreened place settings directly onto the studio floor. She considered this event, a performance that was also a work of art and a social gathering, as a way to explore the relationship between her work and its effect on her viewers—her dinner guests.

A year later Lake purchased her first single-lens reflex camera and began to combine performance with photography: her initial effort was the 16mm film Bisecting Space, 1970, in which she silkscreened a dotted line on a two-hundred-foot sheet of muslin and placed it along the floor and ceiling of an empty gallery space in the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (MMFA), dividing the space in two. “I used the fabric to bisect the space to feel the perceptual impact on the body’s awareness of space/area,” she explains. “I first did this in 16mm film in a gallery at the MMFA; but the cumbersomeness of the equipment was distracting to the experience, and the 2-d projection reduced the activity to documentation of process. I re-did the activity … as a private performance in my studio [in order] to focus on the experience, with a minimum of stills to document it for my own record.” As with her performance picnic with Tom Dean, this work is an early instance of how performance and its documentation were becoming increasingly entwined in Lake’s practice.

Although greatly influenced by the dominant artistic styles of hard-edged abstraction used by Guido Molinari, Serge Tousignant (b.1942), Yves Gaucher (1934–2000), Hugh LeRoy, and others, Lake gradually transitioned to using camera-based forms of media; as she said, “I had to step away … to not fall back on the old tropes of painting. So I chose to work in photography and video, and a lot of the early performance and video that I did do were issues that I was learning from the senior artists. I wanted to try to understand them, to perform them with my body.” At the time, camera-based art was still a relatively new medium compared with the long-established practice of painting. It offered innumerable avenues for exploring representation.

Lake’s interest in self-portraiture increased in the early 1970s and she produced several series of photographs of herself in different outfits and makeup, in some works speaking to someone off camera and in some even transforming feature by feature into another person who was important to her. Her goal in all these photographs was to explore an aspect of a constructed and composed identity—often in a playful manner bordering on slapstick.

On Stage, 1972–74, Lake’s first photographic performance series, reacted against the way women were represented in the mass media. By photographing herself as she played different roles and in various costumes and cosmetic applications (including whiteface), she used her own body to explore issues of beauty, identity, perception, and advertising. Lake went on to further investigate the concepts of identity and appearance in multiple portraits arranged in a grid pattern in A One Hour (Zero) Conversation with Allan B. and Miss Chatelaine, both from 1973. In the former, Lake once again appears in whiteface, the title alluding to a conversation Lake is having, presumably with Allan Bealy, outside the photographic frame. In the thirty images, presented in grid formation, that constitute the work, Lake smokes a cigarette, grimaces, and appears to pause to listen to her interlocutor. With a black marker, Lake has circled her head on seven of the images, mimicking a photo editor’s markup on contact sheets, and suggesting a self-consciousness with regard to the dissemination of her image in the media.

A few months later, Lake started her Transformations series, 1973–75. She opened the body of work with a self-portrait and gradually, by replacing one facial feature after another, morphed her image into that of another person, such as Wayne State University colleague Gary William Smith or the Quebec dancer and artist Françoise Sullivan (b.1923). Lake identified Adrian Piper (b.1948) as a pivotal inspiration at this time: “She was a strong influence beginning with her Mythic Being performance series. She was addressing identity ramifications of social change in the late sixties. About that time, I was questioning the representation of women resulting from that social change.” In The Mythic Being, 1973–75, Piper performs for the camera as a somewhat androgynous, racially ambiguous man. Piper’s alter ego first appeared as advertisements in the Village Voice, and over time she began to manipulate the surface of the photographs with word balloons containing text from her journals between 1961 and 1972. Certain textual information and juxtapositions included in works in the series open up the possibility of reading the series as a commentary on racialization and identity construction; I/You (Her), 1974, for instance, juxtaposes Piper’s face alongside the face of a white woman, while the accompanying speech bubble offers the text, “You punish me for how I look, when that is irrelevant and out of my control.” The Mythic Being Cruising White Women, 1975, though not describing the racial identity of The Mythic Being, nevertheless enters concerns over race and racialization into a reading of the work via its titling.

Although Lake’s art from these years can easily be interpreted as feminist, she did not conceive of it that way: “My politics originated in human rights issues, civil rights, the FLQ in Quebec, and race issues in the States.” This description is important: although the feminist movement was emerging in the early 1970s as a distinct rights movement with its own specific political and visual strategies, Lake was more invested in the local struggles that surrounded her and their links to global liberation movements. In particular, she was influenced by the dominant political struggle for sovereignty and the alignment of various political groups—most notoriously the militant Front de Libération du Québec, which, despite its violent strategies, was supported both by left-leaning students, academics, and artists in the years leading up to the October Crisis in 1970 in Montreal and, more broadly, by many others throughout Quebec.

In 1976, Lake appeared in a photographic series by fellow artist Bill Jones (b.1946) titled If You Knew Suzy, in which she dressed as heiress-turned-militant Patty Hearst. Following her alleged kidnapping by the Symbionese Liberation Army, Hearst became a member of the group (she later claimed to be suffering from Stockholm Syndrome) and participated in a bank robbery that was captured on security-camera footage. According to Jones, when he asked Lake if she would appear in the work as Hearst, she “showed up the next day wearing a red beret and raincoat and carrying a realistic-looking gun right out of the news photos.”

Véhicule Art

Lake has reflected that by the early 1970s, “the remarkable thing about Montreal at that time is that the generations intermingled, so it felt like a transition. I was fortunate that I had a dialogue with artists in a range of aesthetics and generations.” With a group of fellow artists, Lake co-founded Véhicule Art Inc. in Montreal in early 1972. The establishment of Véhicule responded to contemporary artistic interests and contributed to a new and pivotal network of artist-run centres that provided much-needed exhibition venues for artists working in new media and burgeoning means of expression. According to its early mandate, Véhicule would “provide a non-profit, non-political centre directed by and for artists, that [through] its very operating structure will remain open and unbiased to changing forms and expressions in all the arts … and that will remain a vital place for both artist and public.” As one of Canada’s first artist-run centres, the gallery provided an exhibition space for artists and became an important site for experimental art and independent art publishing. Soon after the gallery opened, Lake exhibited her first iteration of On Stage, followed by a two-person exhibition, Allan Bealy and Suzy Lake, in December 1973.

In 1976 Lake began her Master of Fine Arts studies at Concordia University, graduating two years later. While there she produced her breakthrough series Choreographed Puppets, 1976–77, in which she was suspended in a harness from a scaffold and manipulated by two puppeteers above, with a third person photographing the performance at regular intervals. Lake explored themes of dominance and resistance and, in addition, because the image of her body became blurred in the still images as she moved, the loss of identity. For Lake, the possibility of distorting a photographic image through a long exposure time meant that the technique was invaluable: it offered a critical site through which to investigate time, duration, movement, and perception.

Although Choreographed Puppets attracted modest attention at its first showing at the Optica art gallery in 1977, it has since been recognized as a challenging and forward-thinking work of art and it was included in the retrospective Introducing Suzy Lake at the Art Gallery of Ontario in 2014. William A. Ewing, the founding director of Optica who invited Lake to exhibit Choreographed Puppets, described the dual focus in this work: to use performance to blur the boundaries of art, and to use photography in a new and expressive way that offered her new personal insight. “The uncertainty built into the production of the piece,” he said, “had given her a new awareness of something fundamental in human nature.”

Toronto: Branching Out, Looking In

After a productive decade in Montreal, Lake had attracted the notice of influential figures in the commercial and public gallery scene in Toronto, and she decided to move to the city where the Sable-Castelli Gallery, her commercial dealer, was located. She arrived in 1978 accompanied by her second husband, Alex Neumann. Soon after the move, Lake became a member of a community of photographers who helped to found the Toronto Photographers’ Co-operative (now Gallery TPW); it included Jim Chambers (b.1945), Keith Bassam, Shin Sugino (b.1946), David R. Harris, Jim Adams, and Michael Mitchell (1943–2020). This community had come together in late 1977 to discuss the possibility of forming a photographers’ co-operative gallery in response to concern expressed by many artists over the lack of support in Canada for photography as an art form.

In 1978 Lake had a solo exhibition, imPOSITIONS, curated by Roald Nasgaard, at the Art Gallery of Ontario, and she was included in a group exhibition (titled For Suzy Lake, Chris Knudsen, and Robert Walker) at the Vancouver Art Gallery. The VAG show included three of her photographic series from the time: Choreographed Puppets, 1976–77, and Vertical Pull #1, 1977, as well as imPositions #1, 1977. In the latter two, Lake appears bound with rope so as to investigate issues of confinement, control, struggle, and perhaps empowerment—qualities that she believed could be amplified by heating the photographic film and stretching it to exaggerate the actions documented in imPositions #1.

During this time Lake began work on her series Are You Talking to Me?, 1978–79, which was exhibited at the Sable-Castelli Gallery in 1979, followed by a trans-Canada tour. It marked the culmination of her explorations in identity and gender by documenting one of her own “performances” in black and white photography; she painted some of the images with traditional oil paints and re-photographed them in colour film. Her intention was to manipulate the photograph, with particular emphasis placed around the mouths in the images in an attempt to draw the viewer into the conversation.

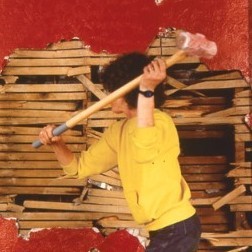

In 1980, while still married to Neumann, Lake gave birth to their daughter, Danika. As she recalls, “When I had my daughter it was like an isolated incident in the community, and you know, I had male artists saying, ‘Don’t you believe in your career? What are you doing that for?’” Throughout the 1980s Lake juggled parenting and working, producing photographic works focusing on the relationship between the figure and space. In the sculptural photo and wood installation Passageways, 1982, different photographs of Lake’s body are assembled in a collage-like formation contained by a wooden structure that resembles two parallel walls. In Pre-Resolution: Using the Ordinances at Hand, 1983–85, which was photographed in Lake’s new home in Toronto’s Christie Pits neighbourhood, Lake is seen taking a sledgehammer to a bright red wall behind her, revealing the wooden slats behind the drywall. In these images she engages in destruction in order to achieve greater freedom by breaking out of the confined space, but is nevertheless contained by the frame of the photograph—this tension is an example of how Lake’s practice of photographing her performance can introduce an altered perception. This series, in which she stands with her back to the viewer, was the last in which she performed for the camera until 1994 (she did a live performance, Missed Liberty, in 1985–86).

Lake ceased appearing as a subject in her work in the mid-to-late 1980s as she became invested in more direct forms of camera activism: for a decade she put her camera and skills to use in more specific political struggles. She began to teach photography as an activist strategy even as she used her camera to document and advocate on behalf of the groups she assisted. On the global front, she focused on power dynamics and grassroots activism, working with ArtNica, a solidarity group that supported the Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional (FSLN) (the Sandinista National Liberation Front) in Nicaragua. While there, she taught the Sandinistas how to take nighttime surveillance photographs of the Contras.

In Ontario, Lake joined with the Teme-Augama Anishnabai Band of Bear Island in Temagami and, at the invitation of the Band Council, produced a series of photographs designed to be an installation in solidarity with their land claim. She had been involved in anti-clear-cutting protests in the province, and the Band hoped she could convey the issues to a majority-white city audience through this collaborative work. Lake decided to work collaboratively on this project and lend her aesthetic skills to draw attention to the issue: “I could talk about issues of authority and power relations through my own work,” she wrote, “but the land claim and the attempts since 1870 to arrive at a treaty were not my stories to tell.”

These experiences, combined with new developments in the theory of photography that advocated a politically conscientious engagement with photographic subjects (in writings by Martha Rosler [b.1943], Allan Sekula [1951–2013], and others), contributed to the development of her installation Authority Is an Attribute … part 2, 1991. In this work she created a photomontage of pictures of some of the Band members before photographs of their special places in the disputed territory, juxtaposed with photographs of two businessmen—called the Game Players—staring through binoculars to scrutinize the location. In 1991 the Band named Lake an “Honorary Friend of the Teme Augama Anishnabai” for her advocacy of their land claim.

Since 1968 Lake had taught in various institutions, first in Montreal and later in Toronto. In the 1980s she became a sessional instructor at the University of Guelph, where she was hired as an associate professor in 1988 and granted tenure in 1990. For the first time, she had a secure income for herself—and she enjoyed her role as an educator:

I loved being in the classroom and inventing pedagogical strategies … As a 22-year sessional veteran, I taught everything from watercolour to performance. Once full time, I was able to focus on media more aligned to my practice, then eventually I was able to focus on photography. In a smaller art program, photo students needed to learn technical, aesthetic/conceptual and historical material. It was a lot to blend each semester, yet it provided the student with means for creative independence.

Lake became famous among her students for her many catchphrases, such as “aesthetic bracketing,” which translates as encouraging students “not to lock in one vision of what the finished work should look like.” Her former student and later studio mate Sara Angelucci (b.1962) says that the phrase “everything is information” became a “mantra” in Lake’s classes.

In 1987 Lake separated from Neumann, and they divorced in 1994. She has been with her partner, Robert Yoshioka, since 1989, and she works from her home studio in Toronto’s Annex neighbourhood. Lake continues to maintain multiple identities—among them, artist, grandmother, and citizen.

Maturity and Recognition

After a quarter century in Canada, Lake’s broad recognition as an artist was firmly established. In 1993 the Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography (founded in 1985 and closed in 2006, its collection absorbed into the National Gallery of Canada) organized Point of Reference, a twenty-year retrospective of her work, which toured until 1997.

Around the same time, after a decade-long absence, in 1994 Lake began to appear as the subject in her work again, though, in her words, this return marked “the beginning of depicting an older body.” The cotton slip, a metaphor for both vulnerability and armour, became the costume she donned in Re-Reading Recovery,1994–99—and again in the commission Rhythm of a True Space, 2008, at the Art Gallery of Ontario, when the work appeared on a human scale yet elevated by the temporary wooden scaffold that surrounded the building during its renovation. A version of the cotton slip, made of hand-quilted photographic emulsion, was also displayed as part of the 1998 series Fascia, in which Lake created a tactile link between the delicate wrinkled photography film and the texture of her aging skin.

The art Lake made over the next ten years included performance for the camera, as she explored the female body and its relationship to mainstream celebrity and youth culture, notably as Suzy Spice in You Really Like Me #1, 1998, the photo performances series Beauty at a Proper Distance, 2000–2008, and works produced from photo-documentation she took of the Canadian Idol reality TV auditions in Toronto in 2003. These photographs were exhibited by her art dealer Paul Petro Contemporary Art in her 2004 show Whatcha Really, Really Want. Lake’s Peonies and the Lido, 2000–2006, captures a different side of aging—one of contemplation as well as agitation. It depicts Lake as the Dirk Bogarde character Gustav von Aschenbach, an aging composer who travels to Venice and becomes obsessed with the youth and beauty of the adolescent boy Tadzio, in Luchino Visconti’s 1971 film adaptation of Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice.

In 2008 Lake retired from teaching at the University of Guelph and was given the title Professor Emerita. The approaching freedom launched yet another busy period of artistic production and recognition: she was included in pivotal group exhibitions such as WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution, 2007, curated by Connie Butler, at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles—a show that travelled to New York, Washington, DC, and Vancouver. That same year, Lake was exhibited alongside two notable American contemporaries in Identity Theft: Eleanor Antin, Lynn Hershman, Suzy Lake, 1972–1978, at the Santa Monica Museum of Art (now the Institute of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles). Lake has acknowledged the influence that Antin’s work with the body had on her own practice.

The 2010 touring exhibition Traffic: Conceptual Art in Canada, 1965–1980, featured Lake in its Montreal section, alongside former Véhicule artists Tom Dean, Serge Tousignant, and Bill Vazan (b.1933). In 2012 Georgia Scherman became her dealer, in Toronto, because, in Lake’s words: “I was very fortunate to have a gallery on Queen Street [Paul Petro Contemporary Art] that kept my work visible to a younger community, and he did a very good job of that. But I think in terms of a different perspective, I changed galleries because I really did feel that I needed a woman to represent me.”

In 2014–15 the Art Gallery of Ontario presented the retrospective Introducing Suzy Lake. The title was tongue-in-cheek, “introducing” Lake to new generations and audiences when, in fact, she had been working in plain sight all along. Some performance works were resurrected for the AGO’s First Thursday event: while Lake resumed her Suzy Spice persona, Choreographed Puppets, 1976–77, was re-enacted by Toronto dancer and choreographer Amelia Ehrhardt, rigged into a facsimile of Lake’s original scaffolding and animated by puppeteers overhead. Among the new works, Performing Haute Couture, 2014, commissioned especially for the retrospective, extended Lake’s career-long interest in self-fashioning, depicting the artist in a luxury Comme des Garçons two-piece suit before a dark grey backdrop. These photographs evoke a high-fashion photo shoot where Lake exerts a different type of command: while most of her figure is in sharp focus, her right arm is blurred by movement.

The AGO retrospective also featured two new photographs for the series Extended Breathing, 2008–14, where Lake tests the durational capacity of her aging body as she stands perfectly still in various sites, both private and public, for an hour-long photographic exposure. While the background remains crisp in the photographs, her body is blurred by the gentle movement as she breathes, save for her feet and lower legs, which remain in sharp focus. Extended Breathing also marked a notable return to Lake’s hometown of Detroit, where, in Extended Breathing on the DIA Steps, 2012/2014, she stands in front of the Detroit Institute of Art and, in Extended Breathing in the Rivera Frescoes, 2013/2014, before Detroit Industry, South Wall, 1932–33, by Mexican artist Diego M. Rivera (1886–1957), one of the two largest murals Rivera painted for the institute. Lake further explores her own roots in Detroit in the series Performing an Archive, 2014–16. Through a combination of family documents, genealogical charts, census records, and personal recollection, she created a visual map of her Detroit ancestral homes, juxtaposing neighbourhood maps with photographs in which she also appears.

Following on the heels of her groundbreaking AGO retrospective (Lake became one of only a handful of women artists in the gallery’s history to receive a solo show with an accompanying publication), in March 2016 Lake was honoured with a Governor General’s Award in Visual and Media Arts and, in May 2016, she won the Scotiabank Photography Award, leading to a solo exhibition at the Ryerson Image Centre in 2017. Today Lake’s work is held in several national and international collections, including at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery (Buffalo), the Art Gallery of Ontario (Toronto), the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, the Musée d’art contemporain (Montreal), the National Gallery of Canada (Ottawa), and the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York).

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements