Sorel Etrog was a prolific artist who worked in diverse media, his career comprising clear stylistic periods defined by a broad range of inspiration. Although best known as a sculptor, especially in bronze, Etrog was also a painter, an obsessive draftsman, a poet, a composer, a filmmaker, and a collaborator on multimedia works. Despite its variety, however, Etrog’s oeuvre consistently revolves around tensions that inform human existence, such as the desire for connection, the joy of movement, the inevitability of separation and loss, and the persistence of organic life in a mechanized environment. Some pieces even include actual connecting devices—links, hinges, bolts, nails, and screws.

Painted Constructions (1952–60)

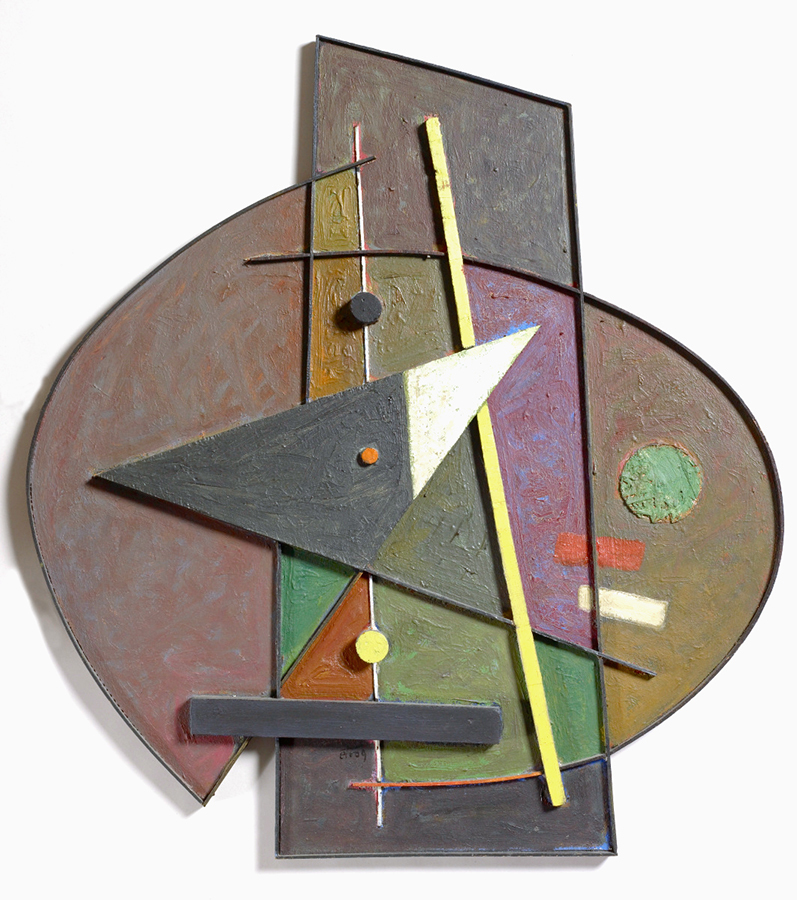

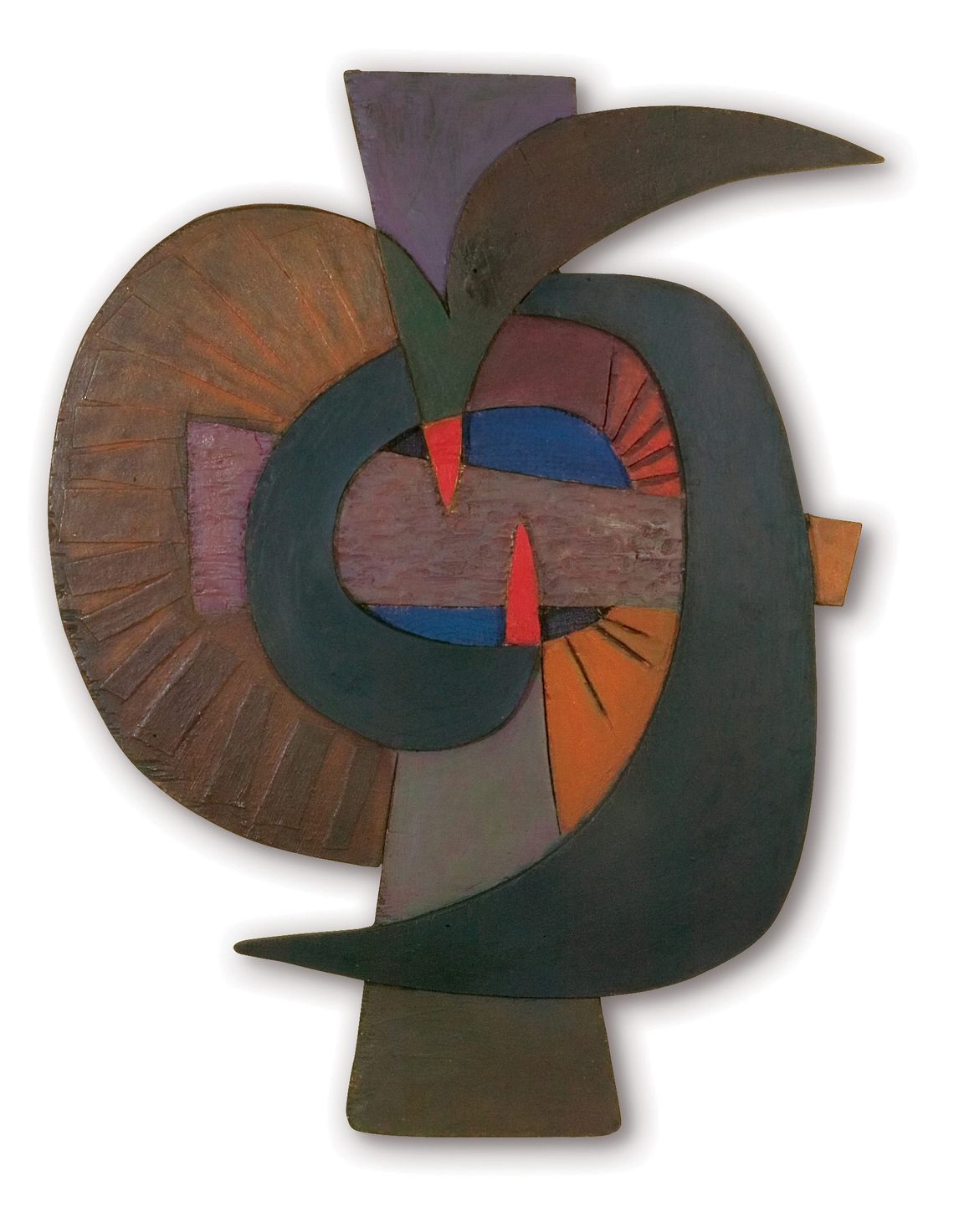

Etrog developed his Painted Constructions as a student at Tel Aviv’s Arts Institute for Painting and Sculpture from 1953 to 1955. At the time he found inspiration in the European avant-garde, a group of artistic movements from the early twentieth century that expanded the definition of art by breaking free of tradition. Influenced by Cubist collage, Constructivist relief sculptures, and artists such as Paul Klee (1897–1940), Joan Miró (1893–1983), and Pablo Picasso (1881–1973), Etrog challenged the separation of painting and sculpture.

“I became dissatisfied working with the canvas and I started to construct my paintings directly on wood. This way I could extend even further the irregular frame and the raised contours outlining shape and colour,” Etrog explained. The constructions resemble conventional paintings insofar as they are painted in oil and are hung flat on the wall, but they are multilayered, forming compositions that playfully defy standard uses of the materials. Etrog builds up the surface by gluing or nailing together wood panels of different sizes and shapes. He then adds a layer of raised lines—some straight, some curved—and forms—triangles, circles, multisided shapes—in order to emphasize their irregularity. A final layer is applied by painting the surfaces in deep, saturated colours, often in shades of brown, yellow, red, purple, and orange, the juxtaposition of hues contributing to the overall complexity of the artwork.

Society of Triangles, 1954–55, typifies this style. The central form is an irregular rectangle flanked by two half squares with a triangle overlaid on top. The next layer is composed of circles, criss-crossed lines, and overlapping geometric figures. This asymmetrical organization is echoed by an inconsistent use of colour. Etrog explained that during this time he was inspired in style and subject matter by the modern atonal music of composers such as Béla Bartók (1881–1945), Arnold Schoenberg (1874–1951), and Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971), who deliberately avoided harmony and balance in their creations: “While I worked my ears were full of the rhythms of the modern music I was listening to, and it came as no surprise that this became the theme of a group of works—strings and bows intersecting each other, dividing the space, a different colour for each instrument.”

These works were the subject of Etrog’s first solo show, held at the ZOA (Zionists of America) House in Tel Aviv in 1958, shortly before Etrog left Israel to study in the United States. The ingenuity of his works led one critic to write that Etrog, even at this early stage of his career, was one of Israel’s most original young artists.

Early Sculpture (1959–63)

Etrog’s shift from flat two-dimensional works to full three-dimensional sculpture was first reflected in his later painted constructions. One of these, The Encounter, 1959, resembles the sculpture Barbarian Head of the same year; the two are composed of similar crescent shapes and both use physical forms and empty space to create an interplay. The Encounter, still two-dimensional, can only hint at this kind of drama. In Barbarian Head the solid forms of the sculpture are accentuated as their opposite and negative space is explored, giving the sense that the sculpture is near its structural breaking point.

Etrog’s transition was inspired by his first experiences of non-Western art, which occurred after his move to New York to study at the Brooklyn Museum School. “Every day at the school I would pass the museum’s collection of African, pre-Columbian, and Pacific Island sculpture. I was struck by the directness of their shapes and started to make numerous sketches. After working with flat shapes all these years I felt I was ready to work in three dimensions and this transition came naturally to me.” At the museum he paid particular attention to small ritual objects from Papua New Guinea, known as kena, which had long handles ending in carvings, often of human figures.

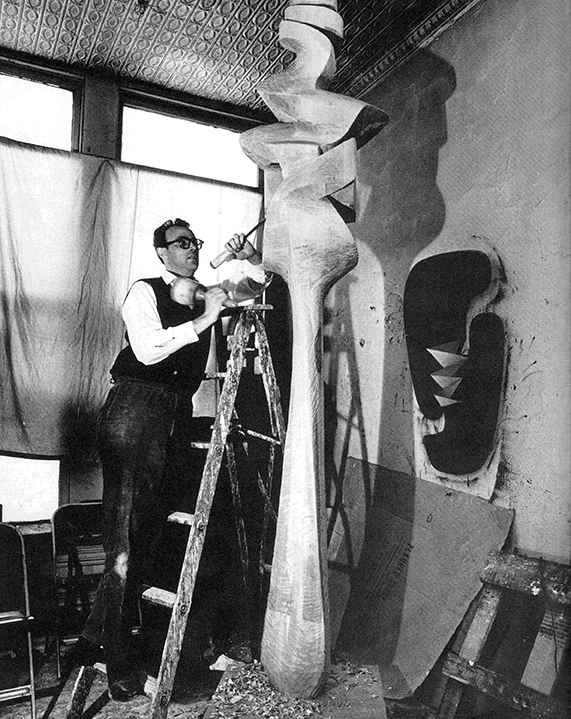

As Etrog’s interest shifted from geometric abstraction to organic forms, he began to create pieces inspired by natural patterns of growth. As in his first sculptures, he explored three-dimensionality and mass but now in elegant balance with clean, elongated lines and vertical compositions. The intention was to create sculptures that would appear to be weightless despite their imposing size and connection to a base. Etrog explored the standing human figure in Africana, 1960, as well as other living organisms. In Blossom, 1960–61, and Waterbury, 1961, two examples that appear to combine the human and the floral, the long stems culminate in circular forms, resulting in something reminiscent of a flower or a tree. Etrog explained that his new style resolved a question of “timing”; he wanted “the figure to soar from the base like the trunk of a tree. . . leaving the drama to the top.”

Sorel Etrog carving Waterbury, 1961, in his New York studio, 1961, photograph by Leslie Shergin.

Sorel Etrog carving Waterbury, 1961, in his New York studio, 1961, photograph by Leslie Shergin.

The Links Period (1963–71)

In 1963, Etrog made his first trip to Italy, where he discovered the art of the Etruscans, the ancient civilization of Italy that preceded the Romans. This encounter led to the invention of his Links motif. It dominated Etrog’s work for eight years, during which he used it to articulate the existential contrasts of human life. As he said, “I saw in [the link] a strong device for connecting and creating tension, mirroring the tension in our very existence with and within the outside world.”

Privately, Etrog gave a biographical explanation for his transition from biomorphic work to his interest in links. In 1966, while living and working in Florence, Etrog witnessed the flooding of the Arno River, which affected him deeply. In a letter to the AGO director, William Withrow (1926–2018), Etrog wrote: “I am witnessing how these past immediate experiences are getting in my new work. I feel certain hardness; the fluid line is being replaced by the links. It gives a more mechanical look. Yet I want to believe that I still speak about the human condition.” He used the link not only to represent the mechanical but also to depict the organic body; through it Etrog examined how elements of the body connect and how they move, sometimes together and sometimes in opposition to one another.

Etrog was attracted to the device both formally and metaphorically for its ability to embody contradictions: the link brings elements together yet allows them also to come undone, and it represents a psychological state as well as physically articulating the mechanisms of the body. Etrog addressed its ability to bind opposites in a 1970 poem, “Links,” which begins: “Art linked to life. / Art linked to death. Temporary witnesses, / linked to one another: linked to the past / linked to the unknown.”

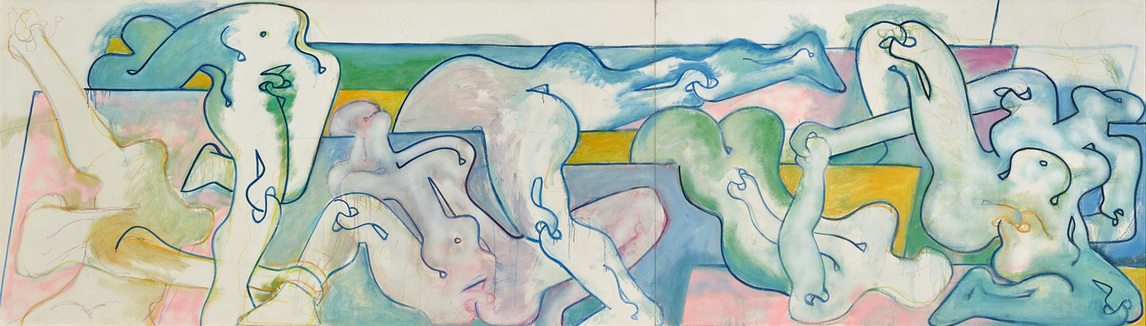

During this time, Etrog created abstract sculptures whose different parts are balanced through a central link (Flight, 1963–64; Survivors Are Not Heroes, 1967) and used the motif to explore dance and movement in the large-scale painting The Rite of Spring, 1967–68. It also provided him with an opportunity to create works that explore familial connections, as in Large Family Group, 1963–64, or to depict individual subjects, as in his portrait of Samuel Beckett from 1969, a print that incorporates a link motif.

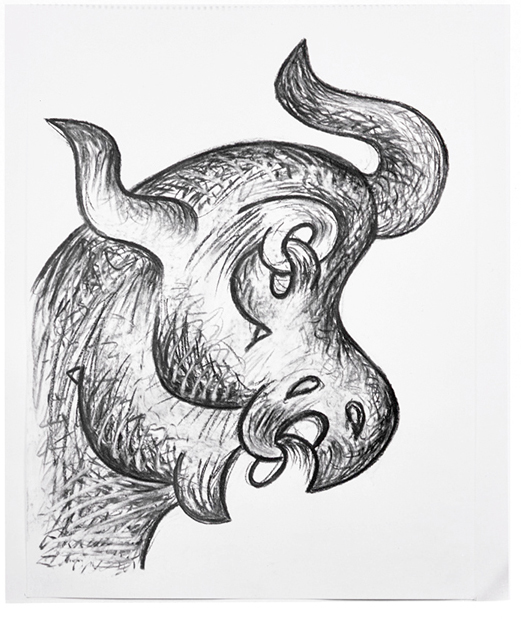

The period ended with Etrog’s brief Bulls phase, which lasted from 1969 to 1970, when he combined link and bull motifs to depict bulls in hundreds of sketches, studies, and fragments as well as in several sculptures. The works are dark in character and testify to the depression the artist was battling at the time, following not only the devastation of Florence but also his life-threatening car accident. In the process of preparing his most important work from this period, Targets (Study after Guernica), 1969, a monumental recreation of the masterpiece by Pablo Picasso (1881–1973), Etrog immersed himself in La Tauromaquia, 1816, the thirty-three-print series of bullfighting scenes by Francisco Goya (1746–1828). Etrog drew many studies, depicting defenceless cows and bulls being tormented in a wide variety of painful positions. In Study for Targets: Three Caresses, 1969, the animals appeared to be hanged upside down and flayed open. The black lines that detail the painting are rendered in an obsessive and chaotic way, enhancing the feeling of horror.

Screws and Bolts (1971–73)

During the early 1970s, Etrog’s work transitioned into an exploration of attachment, using mechanical elements in a new style he referred to as Screws and Bolts, which is typified by sexual, playful, and humorous works filled with life, energy, and colour. He described it as a clear break from what had preceded it: “I don’t postpone an idea. A new one comes and eats up the old one.” He explained that, in 1971, he became obsessed with the screw—another humble fastener—after finding one in the street:

On my next trip to Italy I was going to cast a big trunk full of figurine wax models from my [Links] period. After landing in Rome I drove to my Florence studio. . . . It was late, cold, and I was tired. But the eyescrew. . . was still on my mind. Instead of going to the hotel, I changed quickly into work clothes, found some crackers, opened a bottle of whiskey and worked through the night, making my first plaster of an eyescrew. . . . That trunk of waxes was not opened and even today they remain un-cast. Before long the studio filled up with screws and bolts sculpture.

As Etrog turned his attention to these connecting devices, he was inspired to develop a visual language that expressed the fulfilment of sexual desire through the act of copulation, arising from the everyday association of the word “screw.” At the beginning of this period, he created many studies of the perceived oppositions between men and women and explored male and female anatomies, connecting them in a variety of sexual poses. Later the artist used the motif to create numerous calligraphic drawings in which he developed what appears to be an alphabet for a language of his own invention.

The sculptures of this period are vastly different from Etrog’s other work. He still made use of the traditional technique of bronze casting, but instead of allowing the dark shiny patina to remain on the final surface, he chose to apply vibrant enamel paint in bold primary colours, a rare choice in his sculptural career and one that he would repeat only for Spaceplough II, 1990–98 and in his final Composites series.

Although it is tempting to associate the bright, shiny colours and humour of the Screws and Bolts sculptures with the style of Pop art, prevalent in the 1960s, Etrog was referring to Surrealism, borrowing themes from this interwar avant-garde movement known for its exploration of sexual themes and erotic desire, taken up by artists such as Jean Arp (1886–1966), Salvador Dalí (1904–1989), Man Ray (1890–1976), and Meret Oppenheim (1913–1985). With sculptures such as the explicit Northeast, 1971, Kabuki, 1971–72, and Sadko, 1971–72, Etrog defied the expectations of gallerists and collectors by creating works that he described as “fresh, funny and erotic.” Writers and critics expressed their surprise: one journalist noted that when exhibiting the works in Toronto, “[Etrog] has been on the receiving end of argument and rib-nudging” because of what was perceived as their “sexiness.” In their view the works were sensual and erotic but not “sexy.” The French art critic Pierre Restany (1930–2003) was more critical, calling the sculptures “second-hand metaphors,” claiming that they “could risk throwing the whole body of [Etrog’s] work out of balance without creating any real possibility for the play of irony or double meaning.”

The Hinges Period (1972–79)

While on holiday in Israel, Etrog became enamoured with a new device for connection and articulation: “I picked up a child’s drawing pad and began to draw. . . The hinge started to obsess me. . . in no time [it] started to dominate my sculpture, first in small wax maquettes and later in an explosion in plaster.” When he turned those studies into their final forms, Etrog returned to the unpainted finish of his earlier sculpture, as he “was nostalgic for the subtle monochrome patina of the bronzes.”

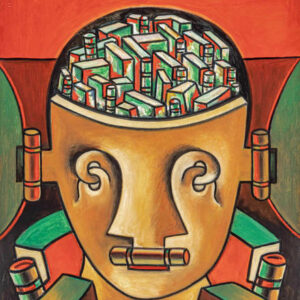

The hinge appealed to Etrog for its ability to connect flat elements firmly while permitting motion. He noted that “the hinge connected the flat surfaces with its tubular swelling, creating a dialogue between the mechanical and the organic.” With it, he returned to his comfort zone, exploring some of the key tensions that play out in human existence: the moment of potential between moving and standing still, between revealing and concealing.

For a short time, Etrog was practising two styles simultaneously—a rarity in the artist’s career. In Pistoya (Mother and Child), 1973–76, the artist blends the motifs of Screws and Bolts and also Hinges: the figures’ heads are made up of the former while the latter are used for the upper bodies. Soon, however, he plunged fully into the possibilities of the new, initiating a period primarily characterized by works that he labelled Extroverts and Introverts.

For the Extroverts, which include Rushman, 1974–76, as well as Pistoya (Mother and Child), Etrog created a variety of walking human-figure sculptures that each express the differences in rhythm, speed, and character of this action. In contrast, Introverts are geometric abstractions, vaultlike objects with surfaces composed of hinged doors that are locked shut, never to be opened. Shelter, 1976, for example, is a symmetrical cube whose surfaces are connected by a network of hinges. The hinges do not open and the possibility of movement is never achieved. Shelter and similar Introvert sculptures speak of the existence of an inaccessible hidden inner core, a powerful metaphor for emotional life and for the inability of human beings to fully know the other, and indeed of the need to lock things away from the self.

While Etrog predominantly used the hinge motif in sculpture, he also created many Hinge paintings, which are characterized by meticulous composition and a high level of finish. In Macrowaves, 1974–75, for example, Etrog uses the new motif to depict a highly stylized seascape of waves that seem to be frozen mid-movement. He also used it in drawings, including Marshall McLuhan, 1976.

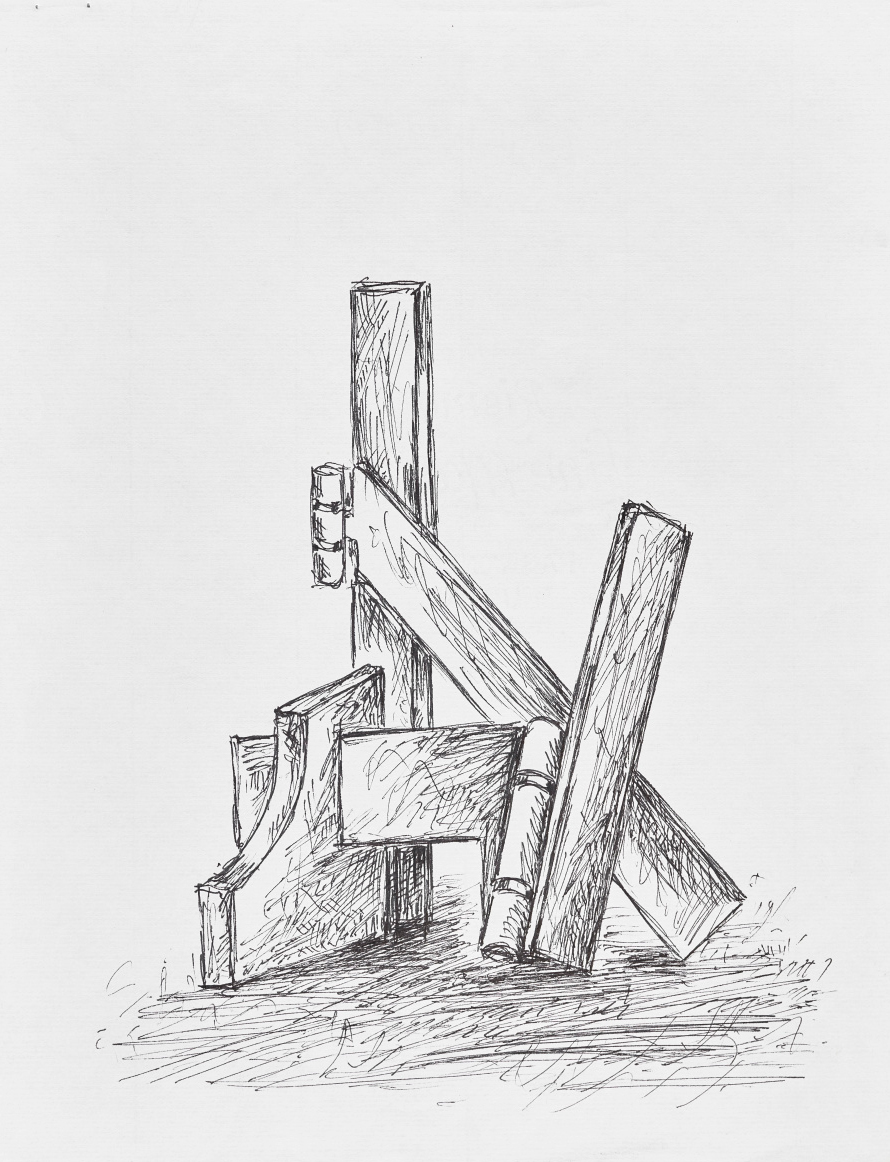

Sorel Etrog’s Sculptural Technique

Bronze was Etrog’s material of choice, and his sculptures were cast using the ancient lost-wax process, imbuing them with a monumental quality. Yet the foundation of his sculptural practice was drawing and sketching. He drew constantly on whatever material he could find—used envelopes, cigarette packs, and napkins, as well as professional drawing paper. These sketches range from a preliminary doodle to an elaborate and fully conceived drawing. They are executed in a variety of media, including ink, gouache, oil, watercolour, acrylic, pastel, charcoal, ballpoint pen, and pencil.

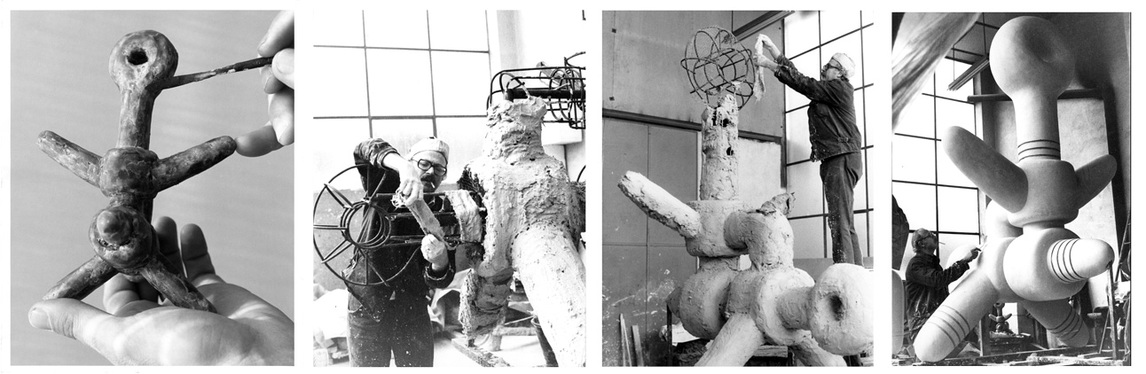

In the next stage Etrog created three-dimensional maquettes—small-scale models—using malleable wax to generate versions of his idea, generally about thirty or forty centimetres high. The most successful of these were then cast in bronze, resulting in many sculptures of varying sizes. Even though they served as studies and preparatory work for large-scale sculptures, Etrog considered them distinctive in their own right, and he often exhibited and sold them.

Etrog would then enlarge the works two further sizes—medium (between one and a half and two metres) and large (taller than two metres). These were considered the full expression of his idea. He would remake each sculpture in plaster by hand to the desired size. During this stage, Etrog would frequently add details or texture the surface of the sculpture; this revising can be seen in the difference between the smooth, rounded exterior of the maquette for Survivors Are Not Heroes, 1967, and the grooves found in the finished piece.

Once the study process was complete, a full-size plaster version and mould was created, which reproduced both the exact form and specific details of the original but as a negative, or hollow, image. Next, the mould was filled with hot wax that, when hardened, created a replica of the sculpture. Vertical wax channels called sprues were inserted into the wax replica, which was then placed in a second mould made of fire-resistant ceramic. The mould was next fired in a kiln. The heat melted the wax, which ran out of the mould so molten bronze could be poured in to replace it and cast the final version. Once the sculpture was released from the mould, Etrog treated the bronze using a process known as patination, which protects the sculpture from corrosion or weathering as well as adding shimmer and shine.

This process can be repeated multiple times to create several editions of one sculpture, a common practice in bronze casting. Etrog’s smaller works were usually made into limited editions of between seven and nine sculptures; medium-size sculptures were typically cast in editions of five or seven, and the largest ones into either a single work or editions of three and five.

Etrog’s commitment to bronze and to the lost-wax process separates him from his peers. During the second half of the twentieth century few artists used this method, and even fewer mastered it. He was exceptional in this sense; having learned every aspect of the casting process in 1960 when he cast his first sculptures at the Modern Art Foundry, Astoria, New York, he performed most of the casting himself, without the help of assistants. The practical knowledge gave him the freedom to stylistically innovate and to push the boundaries of his craft in ways not previously seen.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements