Sorel Etrog’s career was unique among Canadian artists of his time. Although based primarily in Canada from the early 1960s until his death in 2014, he exhibited in the world’s most prestigious galleries and museums and maintained a lively and productive dialogue with leading international artists, curators, and critics—many of whom he collaborated with on artworks in various media. Indeed, Etrog is best understood in the context of early twentieth-century and interwar European avant-garde art movements and the popular philosophies of the postwar years.

Child of War

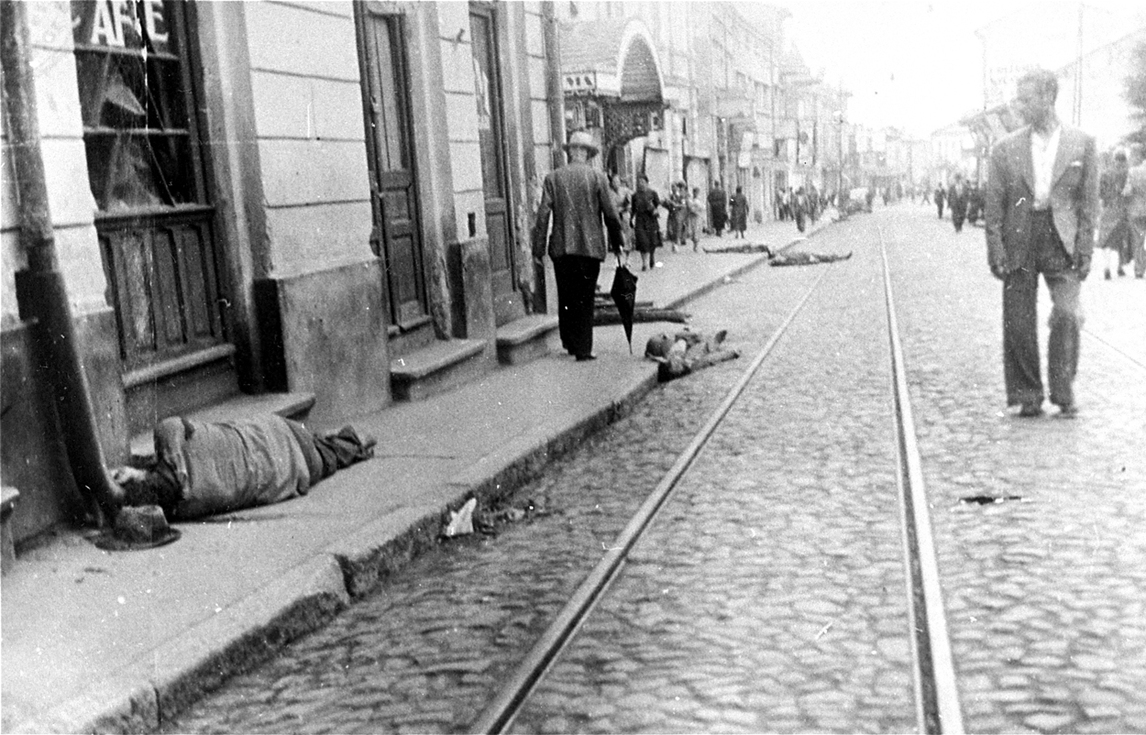

Sorel Etrog was only six years old when the Second World War broke out in Europe and eleven when the Soviet army occupied Iași, his hometown in Romania. The Jewish community of Iași suffered greatly from state-organized violence and anti-Semitism, and the Etrog family experienced cruelty, hunger, and poverty. When the family tried to escape from Romania, Etrog’s parents were imprisoned, leaving him—a thirteen-year-old boy—in charge of his five-year-old sister for a period of several months. Such hardships ended when the family immigrated to Israel in 1950.

Etrog’s childhood traumas undoubtedly shaped him. He only sporadically represented war, violence, and suffering directly in his art, but it is nevertheless a recurring motif of great importance that sheds light on his body of work. His experience as a child of war was first addressed by his working within the tradition of war monuments, prevalent in Europe and North America after the two world wars. War Remembrance Study, c.1959, and War Remembrance II, 1960–61, are two important examples. Both are abstract sculptures that refer to war violence in title and form, as can be seen by the elongated dagger that pierces the sculptures’ round elements. In Survivors Are Not Heroes, 1967, Etrog followed the tradition of war memorials in the sculpture’s size but used it to explore the complex emotions of ordinary survivors rather than to glorify the heroism of fallen soldiers.

In 1966, when Etrog was living and working in the Italian city of Florence, he witnessed the flooding of the Arno River, which killed more than a hundred people and damaged many of the city’s historic monuments and art collections. The experience affected him emotionally and artistically, he confessed:

[T]hese recent experiences brought back to me the war days. I was quite shocked and numb. I am witnessing how these past immediate experiences are getting in my new work. I feel so many things happening in my work, I would have liked to run away from here yet I am in the middle of this development and I should let my work continue even if the circumstances here became so difficult.

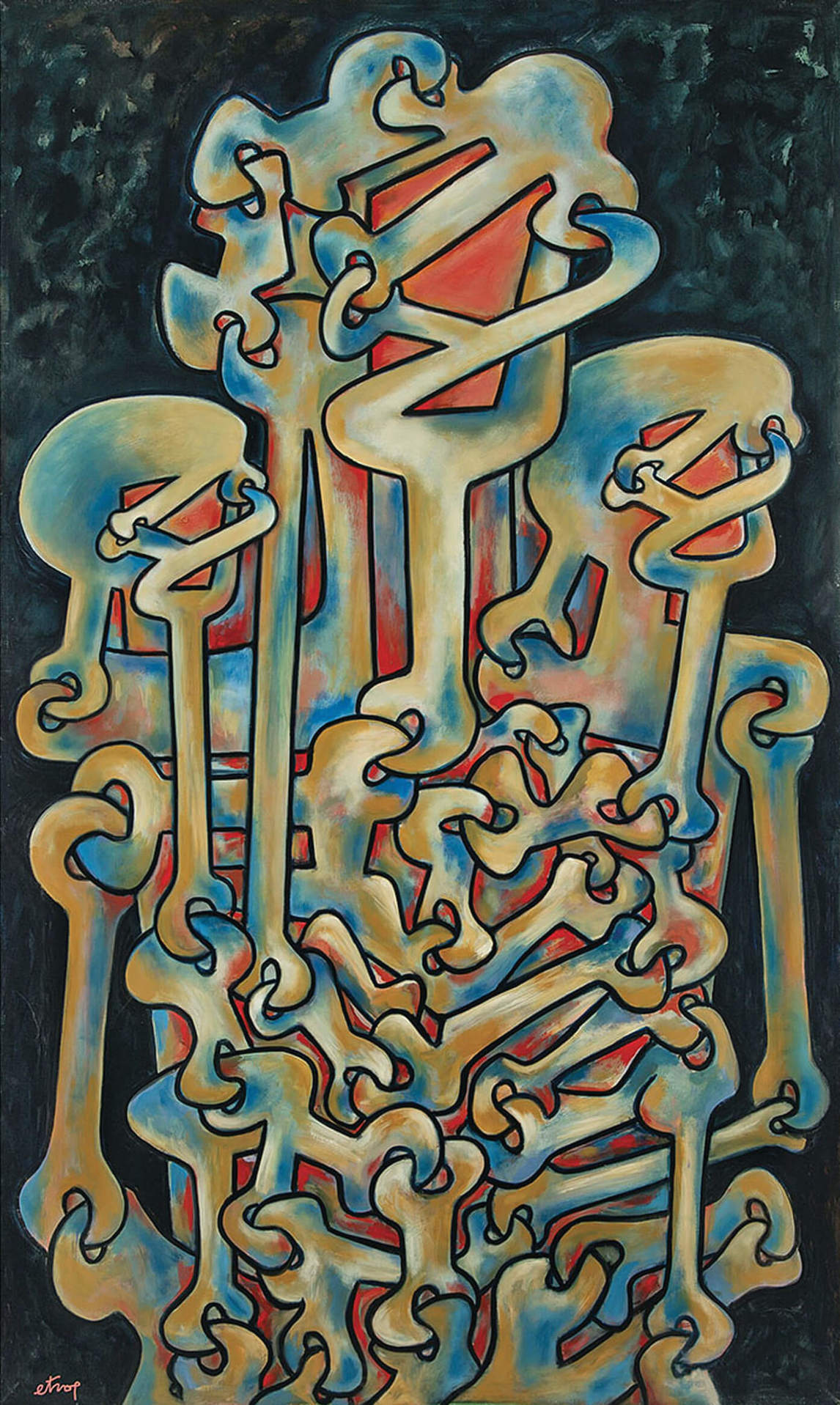

The effect of war is most fully explored in Etrog’s brief Bulls period of 1969–70, when he became devoted to the depiction of harsh and violent subject matter. This intention can be seen vividly in the drawing Targets (Study after Guernica), 1969, his interpretation of the monumental antiwar painting Guernica, 1937, by Pablo Picasso (1881–1973), in which Etrog emphasizes chaos and confusion. Another example of direct representation of the effects of war and violence is in Etrog’s slightly earlier painting Biafra, 1968. The composition of this work was inspired by a photograph that appeared in the Globe and Mail depicting a mother holding two starved children during the 1967–70 civil war in Biafra, Nigeria, where famine was used as a weapon. The three figures are merged into a single mass that seems to be flayed of skin as the artist uses the motif of the link to represent both internal organs and bones.

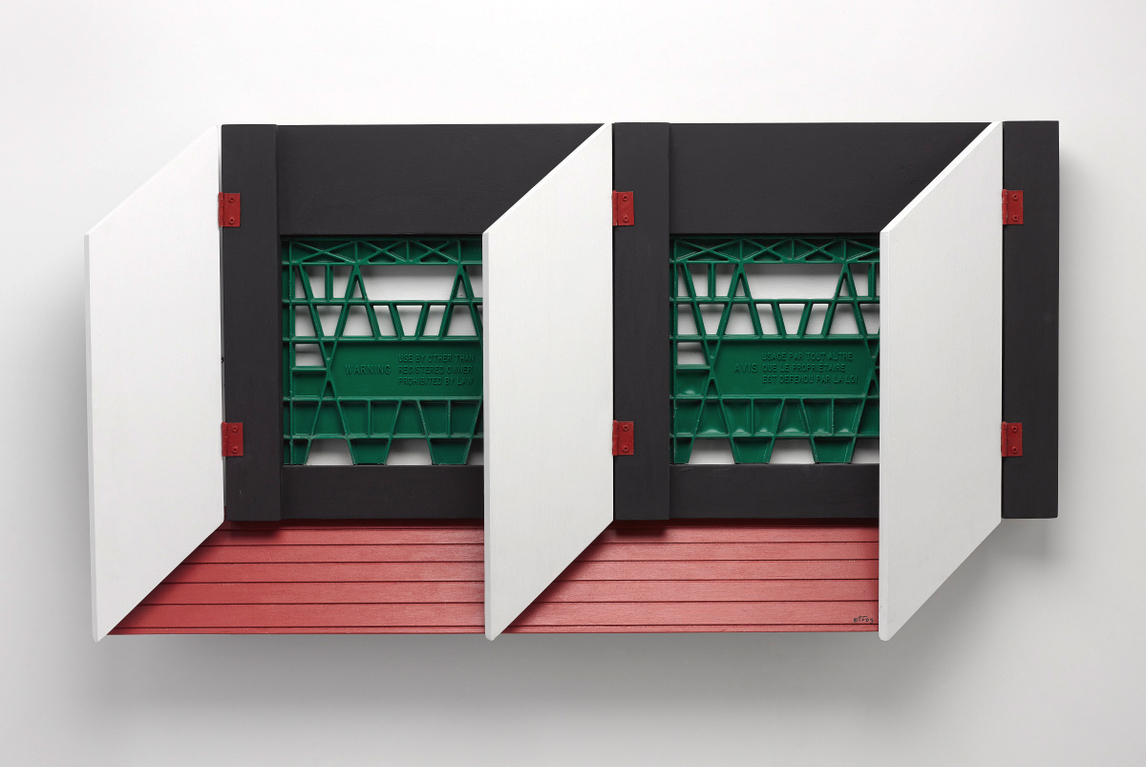

Etrog did not address the theme of war again for a period of about thirty years until, in 1996, he returned to Romania for the first time since he and his family had left the country for good in 1950. The visit brought back painful memories, but it also sparked Etrog’s final body of work, which he called Composites. These are assemblages made of wood and found objects that refer to the trains, barbed-wire fences, prison cells, and concentration camps of the Second World War and the Holocaust. According to Etrog’s close friend the art historian Joyce Zemans, these images reveal what “[lay] hidden below the surface in Etrog’s work,” exposing the importance of Etrog’s childhood experiences and the trauma in his art.

Renewing Tradition in Modern Art

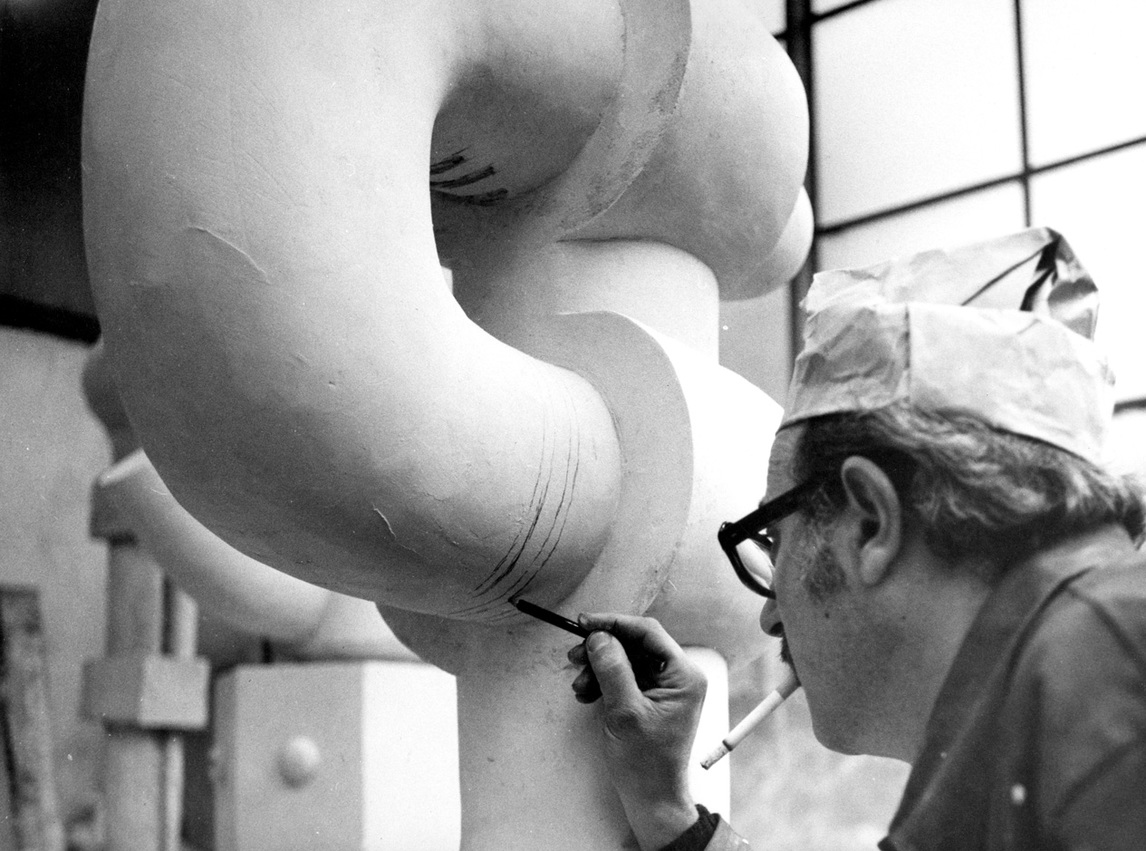

As one of Canada’s leading artists of the 1960s, Sorel Etrog played an important role in the rise of the country’s interest in sculpture. In a 1962 Canadian Art editorial Alan Jarvis (1915–1975), former director of the National Gallery of Canada, commented on the “paucity” of the Canadian sculptural scene, but the critic Hugo McPherson noted in a 1964 Canadian Art article that contemporary Canadian sculptors were moving ahead of the country’s painters, advancing sculpture by searching for new styles, materials, and means of expression. Etrog was included in McPherson’s essay but in many ways appeared to be operating within a different artistic framework than his fellow artists. McPherson noted that Canadian sculptors were using “new media and a new, less subjective vocabulary of forms,” but Etrog continued to work in bronze—in use as a sculptural material since about 2500 BCE—and to employ its traditional labour-intensive casting techniques to create a highly individual repertoire that grew out of the artist’s personal associations, artistic influences, and intellectual interests in the subject matter of the avant-garde. So while he rejected tradition from a compositional sense, he embraced a traditional artistic medium to execute his vision.

The AGO director William Withrow (1926–2018) addressed this quality and its impact on the reception of Etrog’s oeuvre in his 1967 book about the artist:

The work of Sorel Etrog is a rare phenomenon in the art world of 1966. All around us artists talk about the advantages of using one kind of coloured plastic as against another, the superior brilliance of a certain brand of flurescent [sic] paint on the best kind of fractional horsepower motor.… The whole atmosphere of this competitive and entertaining search for novelty is foreign to Etrog. Thus when a jury of professional art experts was recently convened to choose a number of contemporary Canadian sculptors for a large commission, it was immediately suggested by at least one member that Etrog’s name be eliminated out of hand because he works in the “old-fashion[ed] medium of bronze”!

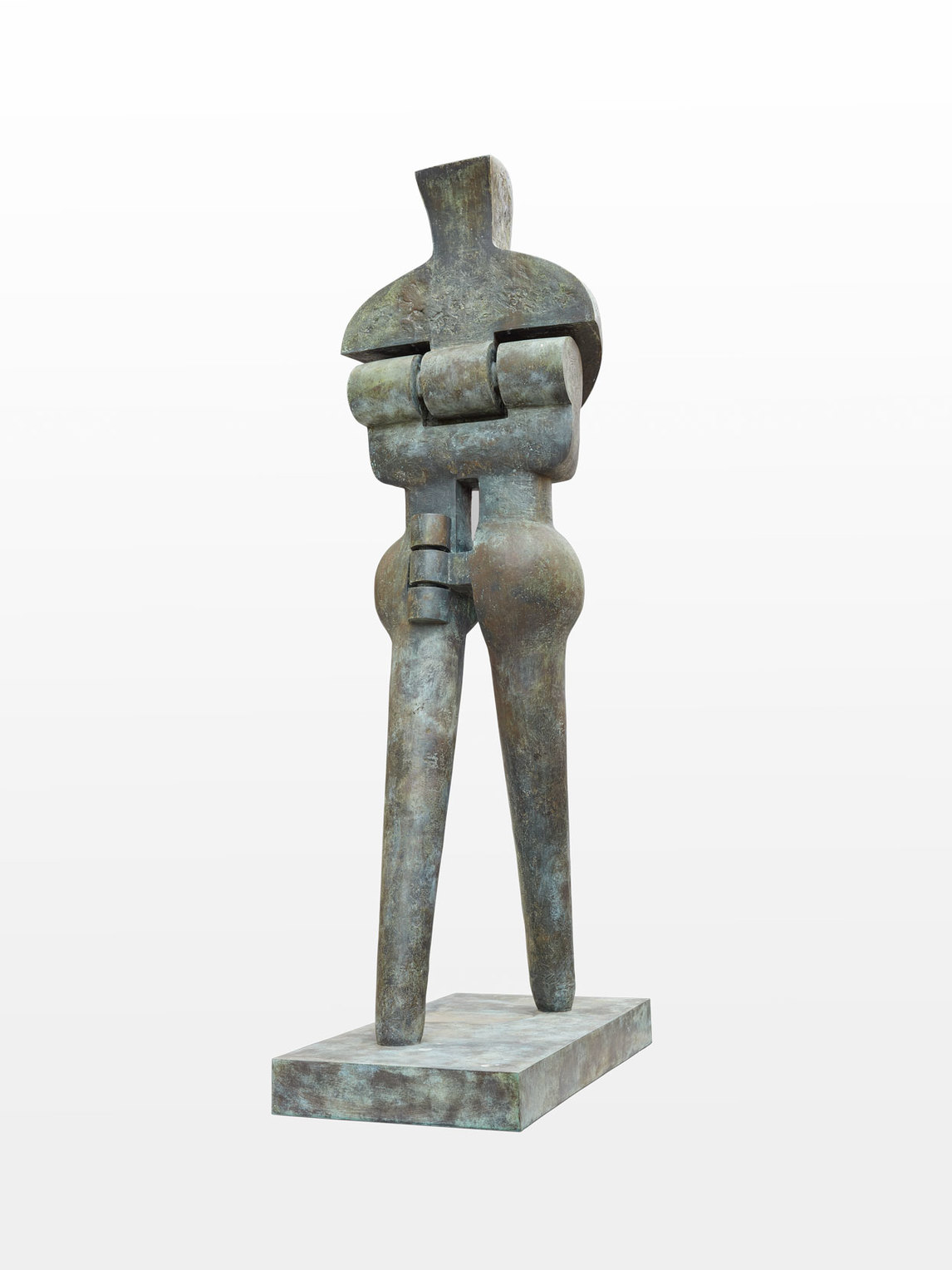

This distinctiveness becomes especially clear when comparing Etrog’s two contributions to the important Toronto outdoor art exhibition Sculpture ’67, a watershed exhibition for public sculpture in Canada, to those of his peers. The Couple, c.1966, and Survivors Are Not Heroes, 1967, are powerful bronze sculptures that Etrog created without assistants. Other contributors to the Sculpture ’67 show, Robert Bladen (1918–1988) and Robert Murray (b.1936), on the other hand, proudly outsourced the production of their work to metal fabricating plants, a common practice among Minimalist artists of the time. While Etrog’s works metaphorically expressed a deep anti-war sentiment (Survivors Are Not Heroes) and the search for human connection (The Couple), Bladen’s contribution, The Rockers, 1965, was absent of symbolism. Similarly, Murray’s contribution, Cumbria, 1966–67, was intended to convey “a feeling for two pieces of steel weighing five tons that can be understood as a long narrow line one moment and a hanging heavy slab or a weightless spread of color the next.”

Other works in the Sculpture ’67 show, such as First, Last by Michael Snow (b.1928), VSI-CirrusCloud by N.E. Thing Co. [Ingrid Baxter and Iain Baxter&] (b.1936), and All Star Cast (A Place) by Les Levine (b.1935), all from 1967, used non-traditional materials such as plastic and electricity and were installed at ground level, encouraging the audience to walk through and under the pieces. They were taking a new approach to sculpture, creating interactive and immersive environments. Etrog, however, remained committed to his interpretation of the European avant-garde through the content and symbolism of his bronze sculptures that sat on pedestals, resulting in what was considered a normal viewing experience.

The Organic and the Mechanical

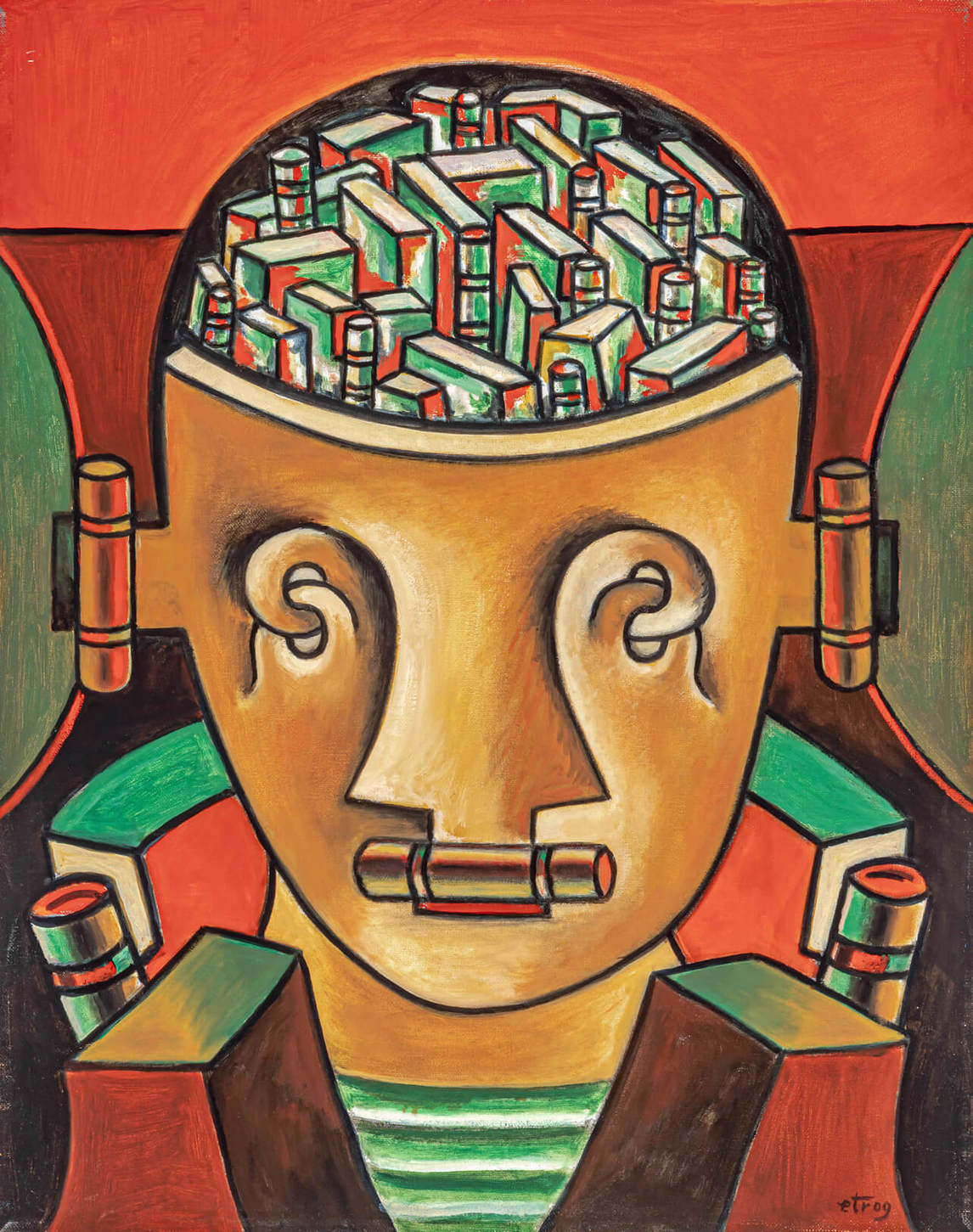

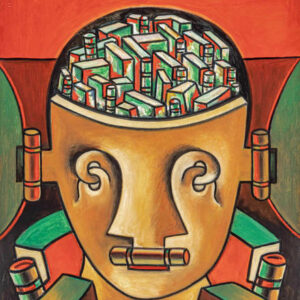

Etrog often depicted the human figure using elements that recall ordinary hardware-store supplies. He named his succeeding stylistic periods after these objects: Links, Hinges, Screws and Bolts. Although he incorporated a mechanical visual language to act as a key structural element and motif in his work, he nonetheless retained a focus on the human experience as if to suggest a blending of the two. The result is artworks seemingly both organic and mechanical, often considered contradictory elements that in Etrog’s oeuvre become deeply intertwined.

One way to understand Etrog’s approach to visualizing this tension between organic and mechanical elements is through his interest in existentialist and absurdist philosophy, which developed as he searched for ways to create meaning out of an irrational world. Born in the decades following the Second World War, these philosophical inquiries were a response to atrocities such as the mass killings caused by the dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945 and the full discovery of the genocide committed by the Nazis in the concentration camps. European philosophers and writers—including Albert Camus (1913–1960) and Jean-Paul Sartre (1905–1980)—struggled to redefine what it meant to be human while artists—for example, Alberto Giacometti (1901–1966), Germaine Richier (1902–1959), and Jean Dubuffet (1901–1985)—portrayed the human body and psyche as wounded and battered. Exhibitions such as New Images of Man, which opened at the Museum of Modern Art in 1959, the same year Etrog moved to New York, also dealt with the consequences of the war and its impact on the idea of humanism, displaying artworks that represented the human body as broken and the human spirit as consumed by anxiety, horror, and dread.

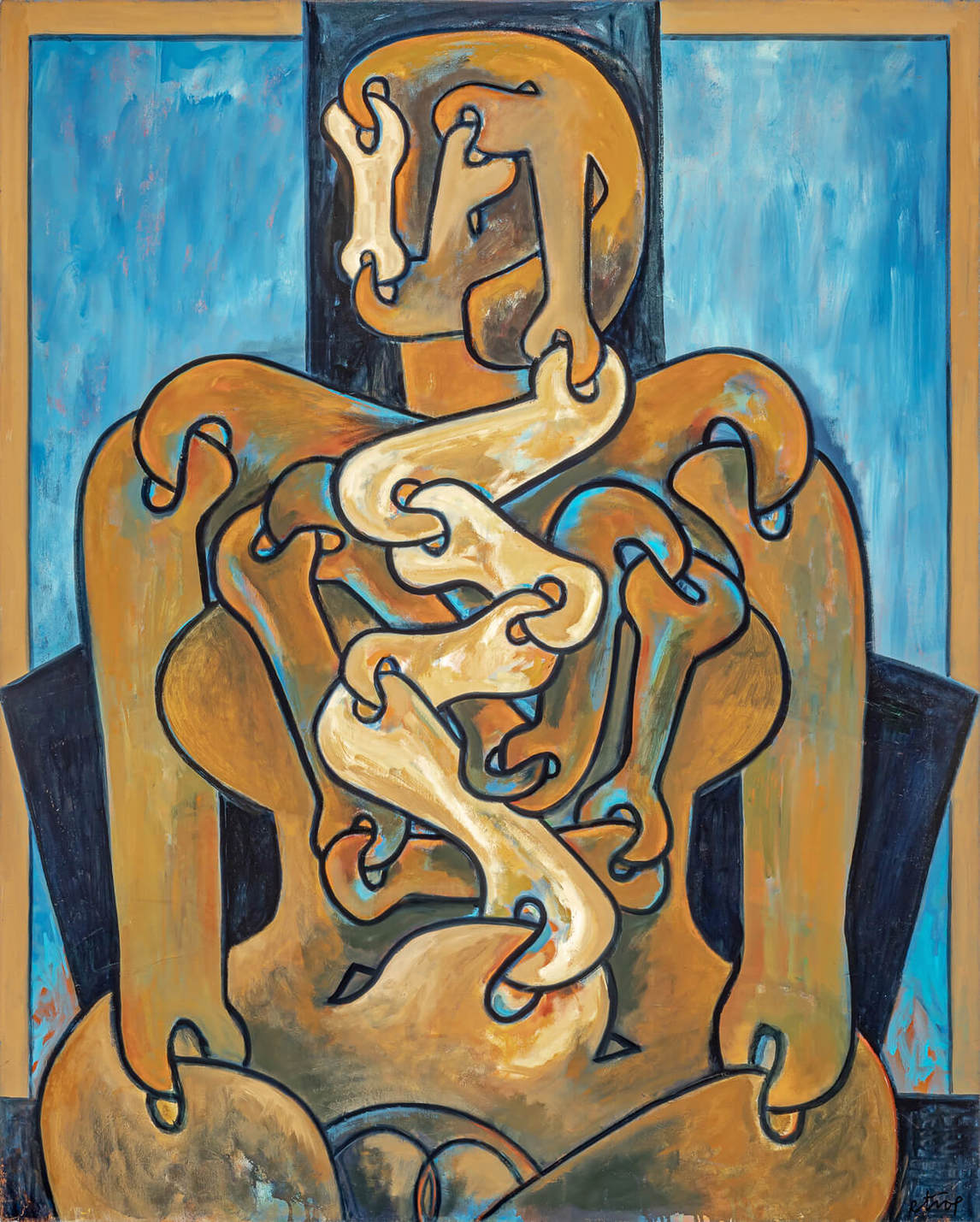

In the following decades, Etrog participated in this critical examination of the human condition by repeatedly depicting the human body as mechanized, allowing him to delve deeper into its operation and to dissect how physical movement occurs. As he explained to his friend the Canadian media theorist Marshall McLuhan (1911–1980), Etrog thought that the body and the machine should be seen as one: “I found that most mechanical tools are an extension of our hand. For me, the mechanical world has a very strong connection with our bodies.” During his Links period of the 1960s, Etrog painted images of men and women that appear to be stripped of their skin, exposing the mechanisms that enable the body’s operations. The torso in Ceremonial Figure, 1968, for example, is replaced by a complex network of links, which resembles an X-Ray image of the figure’s intestines. In Etrog’s Hinges period, the hard edges of the fitting dictate the appearance of sculpted figures, making them look like organisms that are part flesh, part machine, such as in the sculpture Pieton, 1974. In the film Spiral, from 1974, the body and the machine merge memorably, even shockingly, in the image of a naked woman; her outspread legs face the camera, her vagina replaced by a ticking clock.

Collaborations

While best known as a sculptor, Etrog expressed his hunger for innovation through other creative work as well. From the late 1960s onward he forged friendships with prominent intellectual and artistic figures such as the playwrights Samuel Beckett (1906–1989) and Eugène Ionesco (1909–1994), Marshall McLuhan, and the American composer John Cage (1912–1992), with whom he collaborated on many projects. Etrog co-produced artist books, stage and set designs, and multimedia performances, diverse artistic experiments that exemplify the artist’s inventiveness, curiosity, and creative versatility.

Etrog’s earliest collaboration was with the French poet Claude Aveline (1901–1992). The artist first created sculptures inspired by Aveline’s poem “Portrait de l’Oiseau-Qui-N’Existe-Pas” (Portrait of the bird that does not exist) for the Canadian pavilion at the 1966 Venice Biennale, after which he approached Aveline with an offer to illustrate the same poem in a book. This idea materialized in a 1967 artist book titled L’oiseau qui n’existe pas, which reveals the ability of Etrog—himself a writer and poet—to translate words into a distinct visual world, giving the text a new meaning. Combining literature and visual art became a regular practice for Etrog, who designed and illustrated six artist books in collaboration with important writers, including the 1969 Chocs with Ionesco, developed from a poem by the playwright. For the publication Etrog produced a visual counterpoint to Ionesco’s writing; the reading-viewing experience is enhanced by Etrog’s use of different kinds of paper, including transparencies, in his design.

Another example of Etrog’s collaborative practice was a project initiated by Marshall McLuhan. After seeing Etrog’s film Spiral, 1974, the media theorist proposed to the artist that they transform it into a book. In 1987 they published their work, also titled Spiral, which comprised a collage of words and images. Continuing this trend, in 1982 Etrog worked with the composer John Cage on the installation Musicage to celebrate Cage’s seventieth birthday at the Toronto store Edwards Books & Art. Their joint publication, Dream Chamber: Joyce and the Dada Circus, a Collage by Sorel Etrog. About Roaratorio: an Irish Circus on Finnegans Wake by John Cage was released for the occasion.

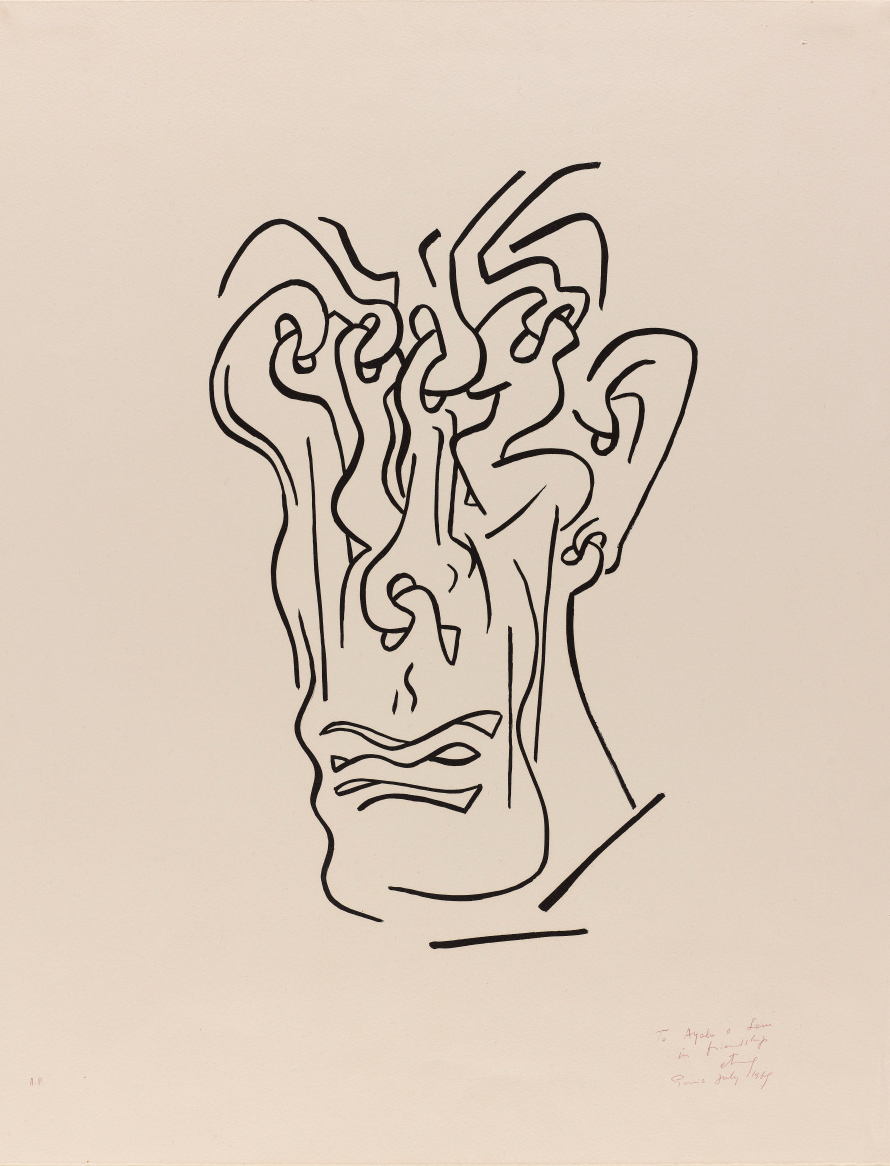

The most meaningful of these friendships-turned-collaborations was the one Etrog forged with Samuel Beckett, the author of the play Waiting for Godot, among many other works. When the two met in the U.K. in 1969, at a function for a project whose funds were donated by Etrog’s Canadian patron, Samuel J. Zacks, Etrog was in his mid-thirties and Beckett in his early sixties; they quickly connected and stayed friends until Beckett’s death in 1989. Etrog later recalled that during that first meeting he immediately began to sketch the writer’s portrait: “Surprisingly I found myself making drawings of Beckett’s head which has still haunted me ever since meeting him. I am not too much of a portraitist, and I would rather say that I tried to capture the inner tension of our meeting. (His? Mine? Or both? I don’t know).”

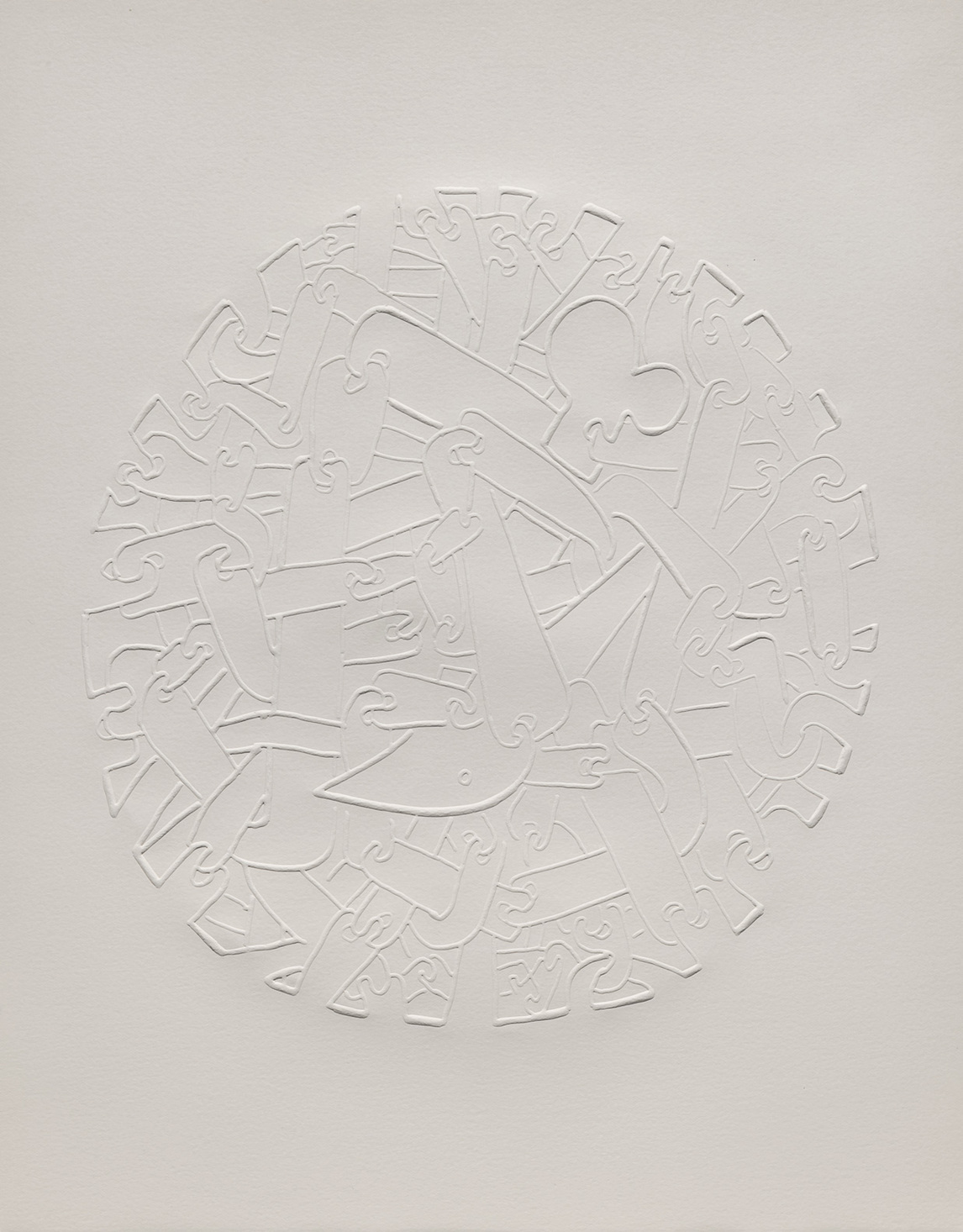

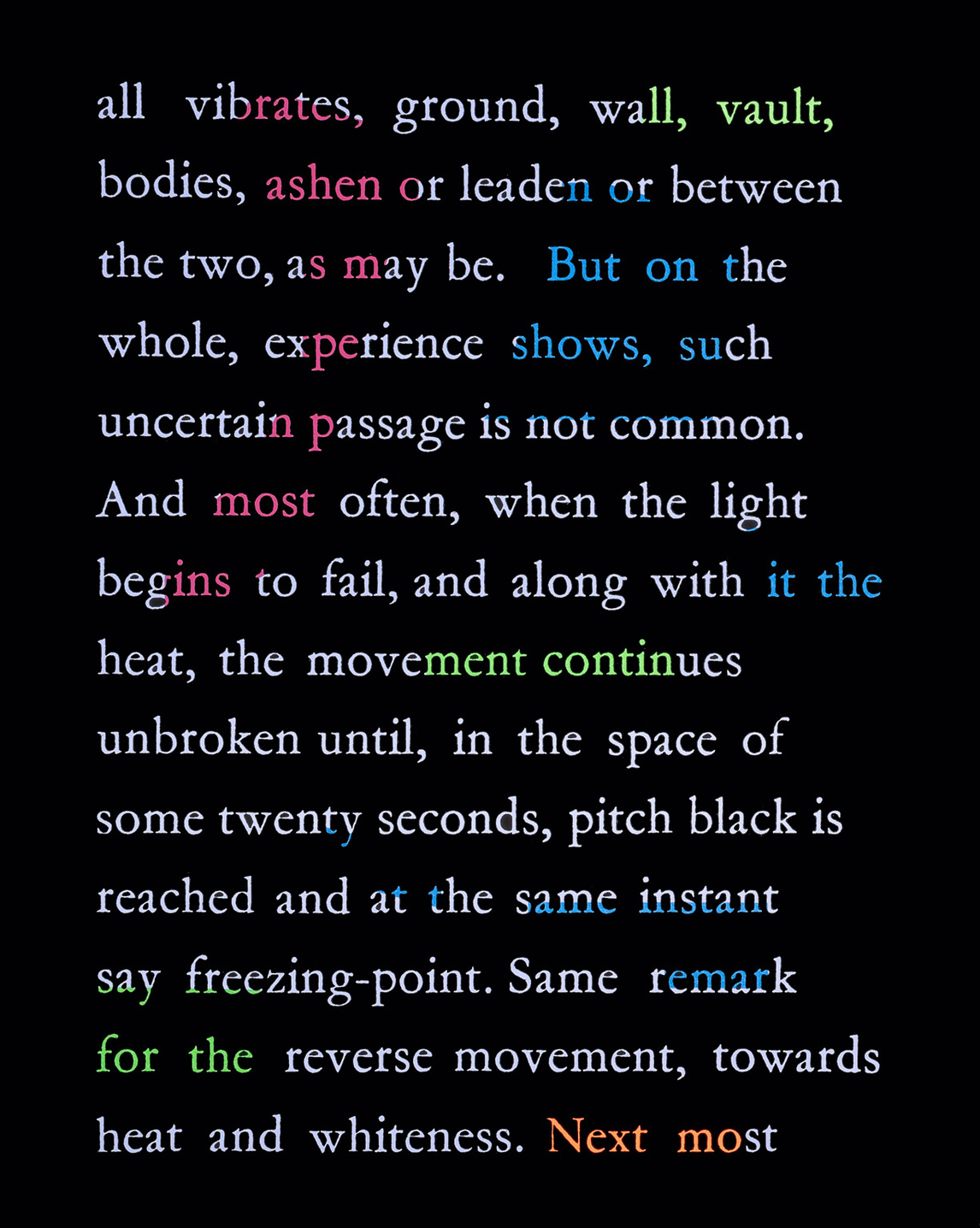

Etrog soon began working on illustrations for Beckett’s short prose text “Imagination Dead Imagine” (1965). The project was not published until 1982, when the Scottish-Canadian writer and publisher John Calder (1927–2018) released a book in a limited edition. The art critic John Bentley Mays (1941–2016) praised Etrog for his ability to “read a modernist text of such intricacy and density as Beckett’s, understand it and—instead of merely illustrating it—re-situate the words in an imaginative visual space which creates, in effect, a new book, with new and emerging meaning.”

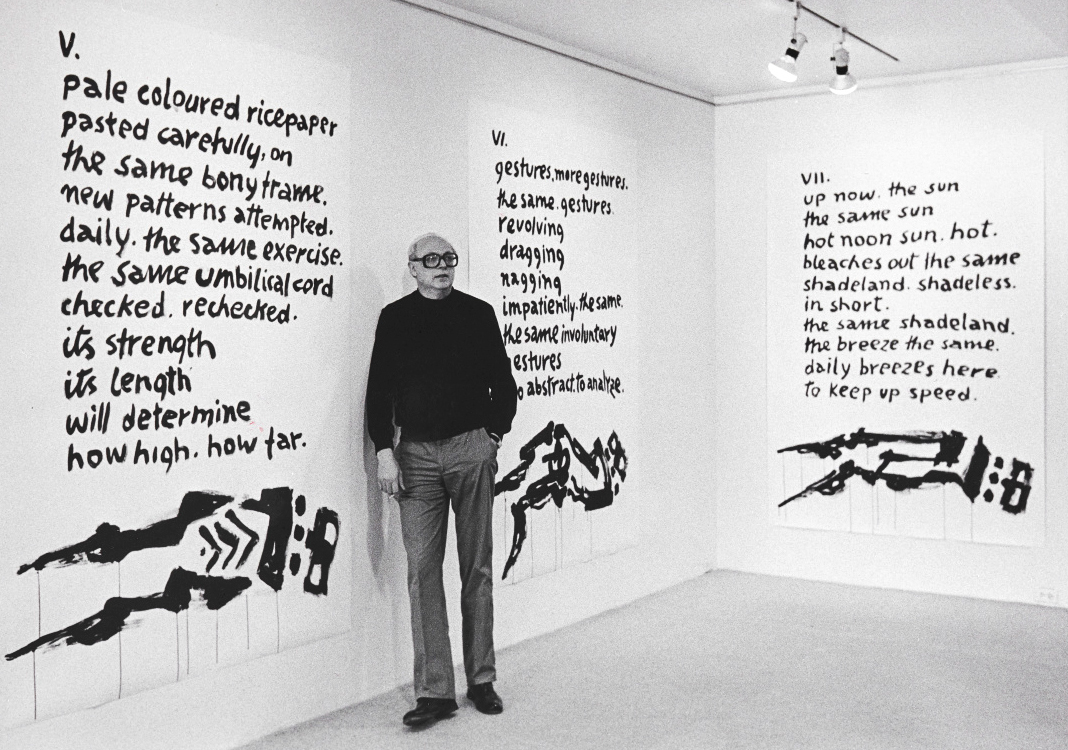

Etrog’s groundbreaking work The Bodifestation of the Kite, 1984, was made in celebration of Beckett’s seventy-eighth birthday. In this performance piece, Etrog inscribed and illustrated his own poem “The Kite” “live” on the walls of Toronto’s Grunwald Gallery, while Gloria Luoma of the National Ballet of Canada danced Etrog’s choreography to electronic music that the artist had composed. Among the approximately 150 people who attended the single performance was Joyce Zemans, who wrote that it was a “moving artwork and a fitting tribute to Samuel Beckett.”

Although these collaborations are lesser-known elements of Etrog’s five-decade career, their importance lies in how they reveal the extraordinary scope of the artist’s talent, creativity, and originality. With them in mind, the large bronze sculptural work for which Etrog is internationally renowned can be understood in the larger context of his ongoing commitment to and hunger for experimentation and innovation.

Legacy

Etrog’s legacy goes beyond his incredible productivity and immense body of work and includes his role as a pioneer of public sculpture in Canada. While few contemporary sculptors follow Sorel Etrog’s commitment to working in bronze—an exception is Montreal-born, New York City-based David Altmejd (b.1974)—his career can be seen as the beginning of a renaissance of sorts. Etrog’s sculptures adorn public and civic spaces in Ottawa, Calgary, Montreal, and of course Toronto, which is home to about thirty. Dozens more can be seen at the Hennick Family Wellness Gallery at Toronto’s Mount Sinai Hospital in an installation that explores the importance of art to physical and mental health.

Within the institutional art world, Etrog’s achievements are recognized at home in Canada and abroad. He lived in Toronto for fifty-four years while maintaining a dialogue with artists, critics, and writers from around the world, exhibiting in all the major art centres of North America and Europe as well as in India, Israel, and Singapore. Leading museums in Canada—the Art Gallery of Ontario, the McMichael Canadian Art Collection, the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, the Beaverbrook Art Gallery in New Brunswick, and Barrie, Ontario’s MacLaren Art Centre—and around the world—the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C., the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, for example—have works by Etrog on permanent display.

Despite his great successes, Etrog’s most significant contribution may be as a model for younger genre-bending artists. He experimented in different media and art forms throughout his career, producing a body of visual and written work that is impressive in its diversity and complexity. Accordingly, he set a vital precedent for contemporary Canadian artists as a polymath who saw no reason to restrict his creativity to a single medium and as a trailblazer who stands as an important example of a Toronto-based yet internationally recognized contemporary artist.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements