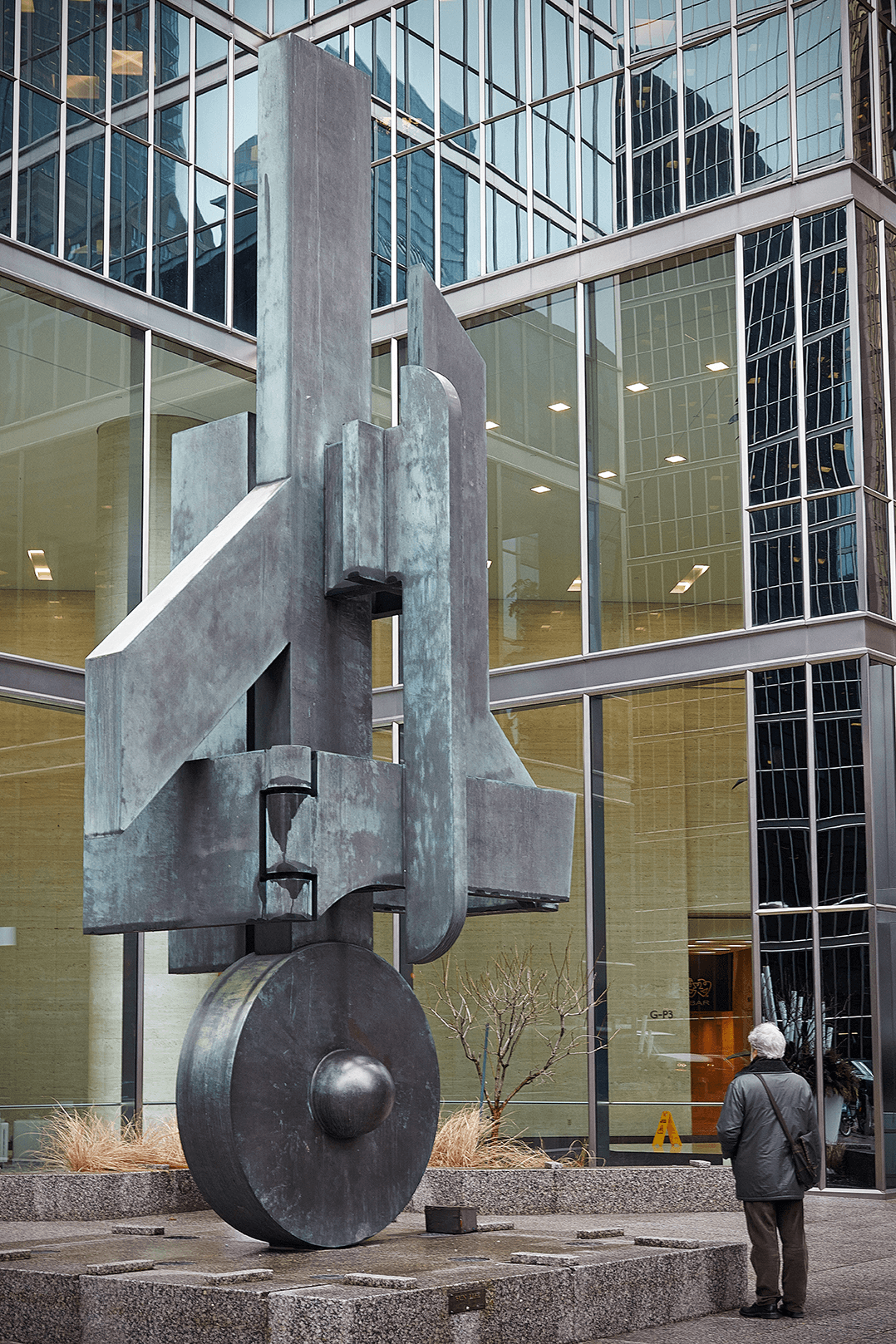

Sun Life 1984

Sorel Etrog, Sun Life, 1984

Bronze sheet and steel, 848.6 cm (h)

Sun Life Assurance Company of Canada, Toronto

Sun Life is one of Etrog’s best-known sculptures, thanks to its great size and its commanding location in the centre of the plaza on the northeast corner of the busy Toronto intersection of King Street and University Avenue. The work presents a relationship between two opposing worlds: the heaviness of its rounded bottom—a “wheel of the sun” motif, which Etrog first explored in sculptures from the early 1960s—anchors the sculpture in the ground, while its vertical top, comprising geometric rectangular forms connected by a series of hinges, seems to pull the piece upward. The fifteen-tonne work measures some eight and a half metres in height, four metres in width, and is three metres deep. It is supported by a two-square-metre, two-thousand-kilogram plate buried beneath the granite paving of the plaza.

Sorel Etrog in his Yonge and Eglinton studio with studies for the Sun Life project, 1981–83, Toronto, photographer unknown.

Etrog won the commission for the headquarters of the Sun Life Assurance Company of Canada following a three-year international competition during which he engaged in his own intensive three-year-long process, creating at least twenty studies in wax from which he selected the one that became Sun Life. It was the first truly large-scale sculpture that Etrog fabricated in Canada, working with Toronto’s Hyland Fabricators, as opposed to his usual practice of working with the Italian Michelucci Foundry. The artist and the local foundry had to overcome several technical challenges. First, because of its size, the piece could not be cast in bronze as a single unit as Etrog would usually have had done, but rather was constructed by laying bronze sheets over a steel armature. Second, the gigantic bronze wheel that anchored the piece had to be produced in the United States, as the Canadian foundry did not have the right equipment for its 170-centimetre diameter. And finally, the welding presented difficulties due to the alloy used.

In his speech at the sculpture’s dedication ceremony, Etrog touched on the problems of public art’s reception and of changing taste. He noted that Toronto lacked public sculpture, despite the existence of many talented local sculptors, and urged city planners, corporations, and developers to invest in this form of art: “Let us not be intimidated nor overrated. Some [sculptures] will be more successful than others, like the building surrounding them. Not every building is a great work of architecture. Yet we need buildings and we need sculptures as well.”

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements