Sorel Etrog (1933–2014) was a truly international artist. He was born in Romania, immigrated to Israel, studied in the United States and, though based in Toronto, Canada, for more than fifty years, worked and exhibited around the world. Best known as a sculptor, he also drew, painted, illustrated books, wrote poetry and plays, and ventured into film. Informed by his childhood experiences during the Second World War and under Soviet rule, as well as by his later immersion in philosophical writings that questioned the nature of existence in a postwar world, he explored the tensions between such apparent opposites as movement and stasis and the mechanical and the organic throughout a long and diverse career.

Childhood in Romania

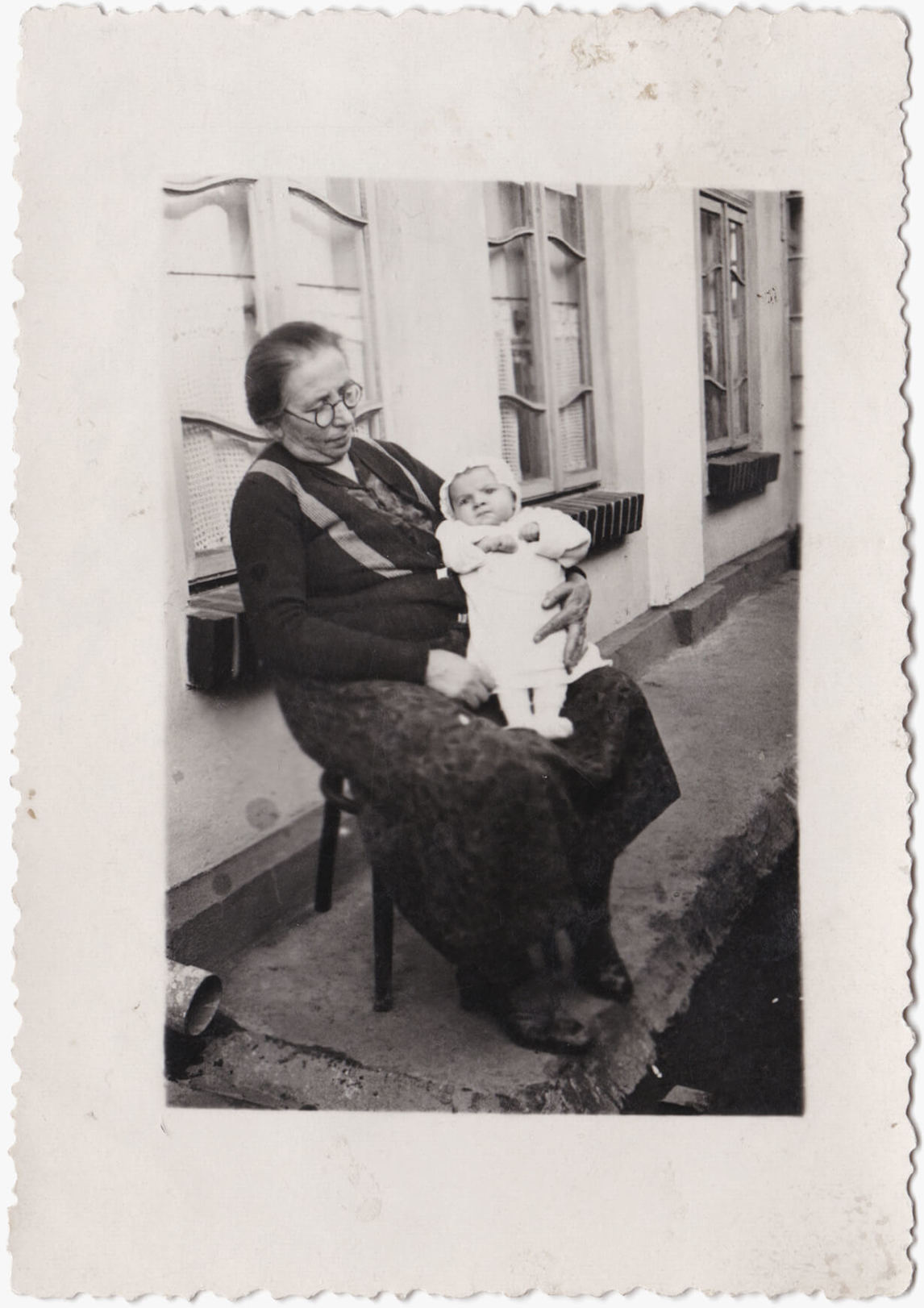

Sorel Etrog was born Sorel Eserik on August 29, 1933, in Iaşi, a large city in the eastern part of what was then the Kingdom of Romania. He grew up just outside the city, living with his parents, Moriţ (Moshe) and Tony (née Valter), in the home of his paternal grandparents. Sorel fondly remembered being in close proximity to his extended family and specifically recalled the influence of his grandfather, a carpenter: “For me his wood shop was like a shrine. The smell of wood, glue, and stain filled my nostrils the day I was born and became a sacred part of my childhood. My dream was that one day I’d be allowed to use some of his tools or even have some of my own.”

The young family eventually moved to Iaşi, where Moriţ opened a restaurant. The Jewish community of the city numbered more than thirty-five thousand people, about a third of its total population at the time. Like many Romanian Jews, Moriţ and Tony were immersed in the local culture and raised their children in the same way: at home they spoke Romanian rather than Yiddish, and though the family observed the High Holidays, Sorel did not receive a Jewish education. In 1940, the Eseriks welcomed a baby girl, Falizia (Zipora), into the family.

Sorel began his informal art education at a local bookstore in Iaşi, whose owner was also a painter. The artist later recalled: “[Since] not many people could afford to buy books… [m]any people, my mother included, borrowed them from a bookshop that was also a private library…. I would slip into the back room to the owner’s studio. He was also a painter. I was fascinated by his… paintings and the smell of turpentine and oil paint intoxicated me.”

The Second World War began with the German invasion of Poland in September of 1939. The Kingdom of Romania was initially neutral, but, following a coup in the summer of 1940, the new dictatorship allied itself with Germany and its anti-Semitic policies. Moriţ was one of the few men to survive the Iaşi Pogrom of June 29 to July 6, 1941, a notorious mass killing in which more than thirteen thousand Romanian Jews were murdered. Although he was wounded, he managed to survive by climbing a curtain in a theatre where one of the massacres took place. Violence against Jews continued throughout the war years, and when Sorel was nine years old, he saw a friend shot before his eyes. Later in life he reflected that after that horrific incident he could no longer be shocked. By the end of the war, Iaşi’s Jewish community had been largely eradicated.

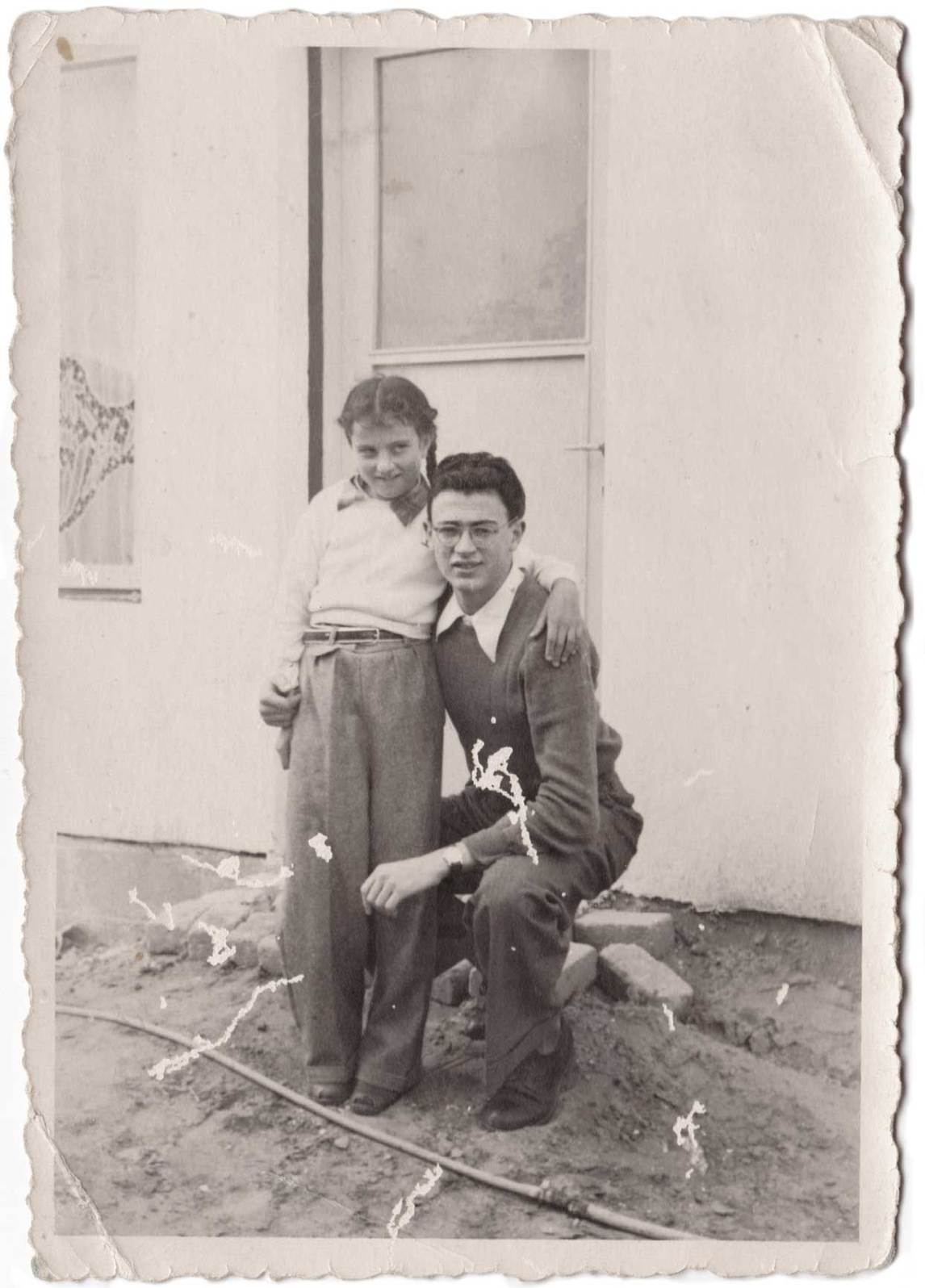

Following the Soviet occupation of Romania in 1944, Sorel’s family suffered hunger, poverty, and violence, and Moriţ still had not fully recovered from the injuries he received during the pogrom. Sorel helped out by smuggling food under his clothes and selling goods on the black market, experiences that shaped him for years to come. In 1946, after quietly selling their property and restaurant, the family attempted to leave Romania for Austria by way of Hungary. But they were caught by the Securitate, the Romanian secret service, at the border and both parents were arrested. Thirteen-year-old Sorel was left responsible for his young sister for weeks until their mother was released. When their father was finally able to go home months later, they all returned to Iaşi before leaving for good in 1950.

Artistic Training in Tel Aviv

Sorel and his family succeeded in escaping Soviet Romania, travelling via Istanbul to Israel, where the Eseriks changed their surname to Etrog—Moriţ and Falizia changed their first names to Moshe and Zipora, respectively. After spending a short time in the Sha’ar Aliyaa refugee camp, located west of the city Haifa, they moved in with his paternal uncle Itzhak in the city of Rishon Le’tzion, where he had lived since before the Second World War. After two years at Itzhak’s humble home, during which time Moshe worked at his brother’s convenience store, they purchased their own apartment with the help of Etrog’s maternal aunt Rose, who was living in the United States.

In 1953 Etrog began his studies in Tel Aviv’s Arts Institute for Painting and Sculpture, while simultaneously serving mandatory time in the Israel Defence Forces’ medical corps as a messenger. At the institute he studied painting, graphic art, and stage design under the painter Moshe Mokady (1902–1975), the Romanian-born Dadaist pioneer Marcel Janco (1895–1984), and the art historian Eugene Kolb (1898–1959). Here, Etrog discovered the art of the European avant-garde, a loose group of early twentieth-century art movements dedicated to defying tradition. Of special interest to Etrog were the painters Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944), Paul Klee (1897–1940), Joan Miró (1893–1983), and Pablo Picasso (1881–1973), who experimented with abstraction and broke free of previous styles and conventions. During this time Etrog became friends with a group of artists who introduced him to the music of modernist composers like Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971), Béla Bartók (1881–1945), and Arnold Schoenberg (1874–1951). Their individual rejection of common notions of harmony and balance inspired him.

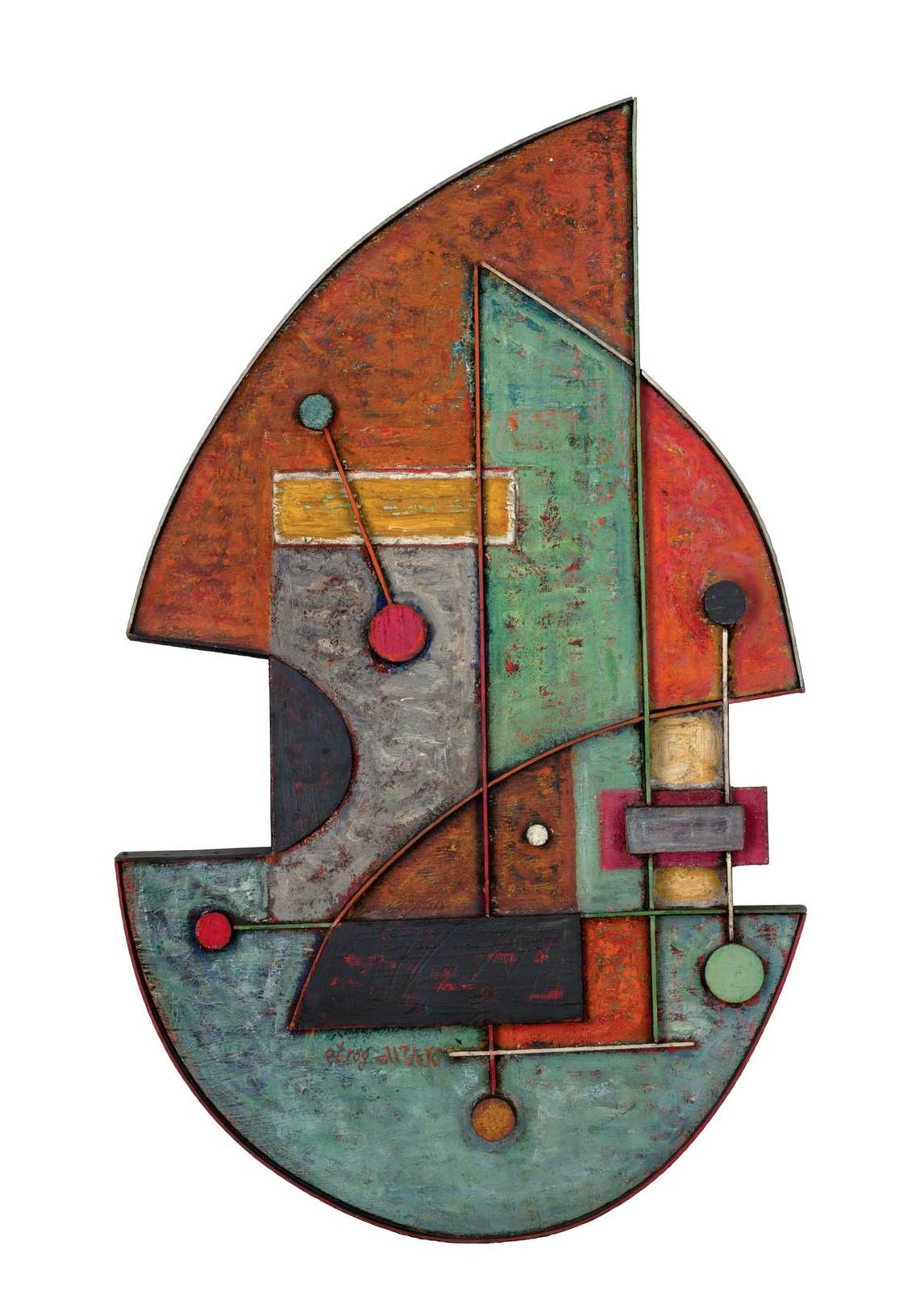

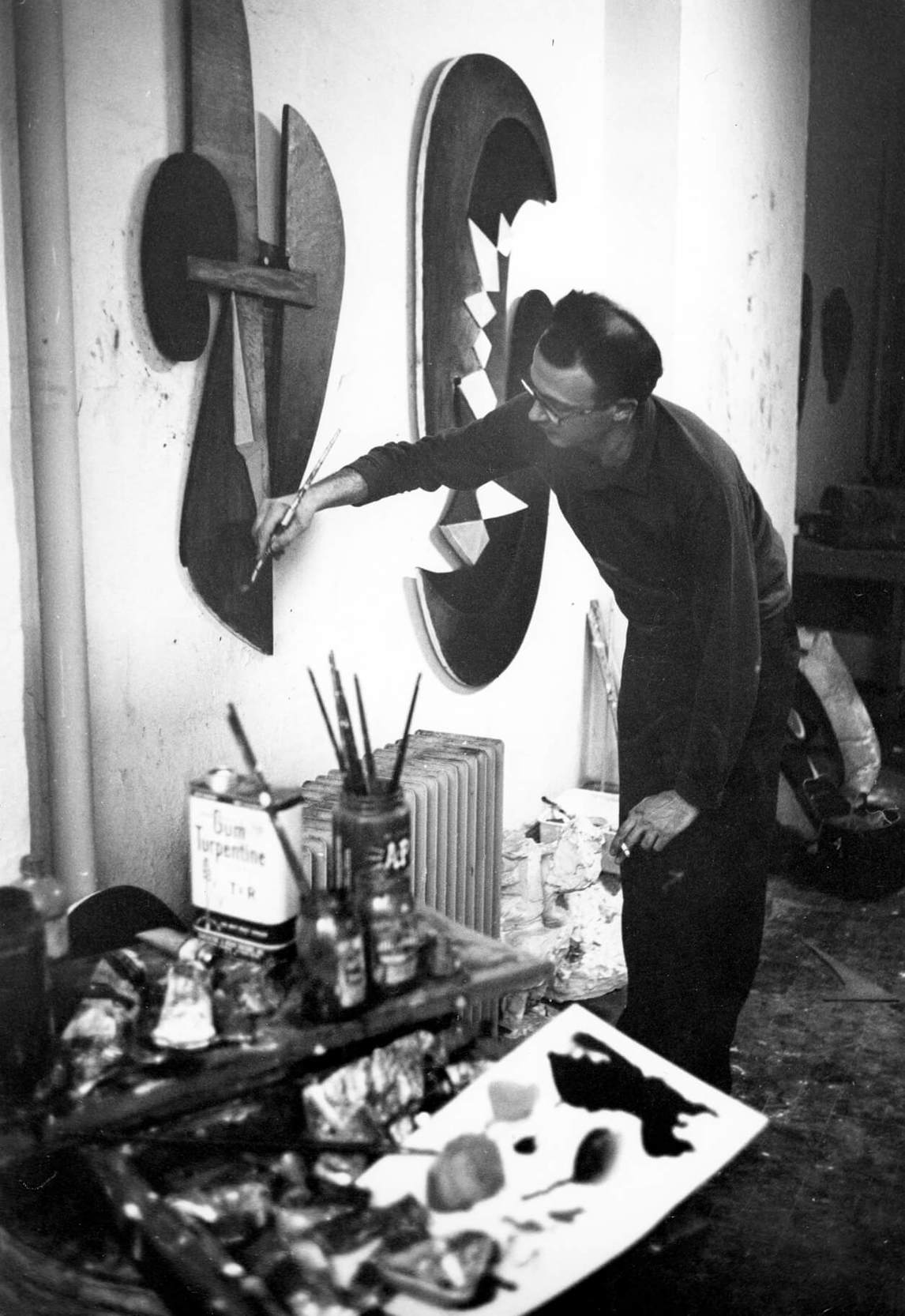

Cubist collage as well as modernist music inspired Etrog to invent a working method that he called “Painted Constructions.” He practised it from 1952 until 1960, honing it through a trial-and-error process, at first using canvases to create the works and then moving to irregularly shaped objects made entirely of wood. They are two-dimensional paintings, meant to hang on the wall, but they also feature three-dimensional raised elements—lines and geometric shapes—to produce works that echo Constructivist reliefs such as those by the Russian-born sculptor Naum Gabo (1890–1977). Despite their overall flatness, they embody an important interplay between sculpture and painting, such as in Musical Impression, 1956.

Etrog’s talent was quickly noticed by his instructors, and after finishing art school in 1955 he was invited by Janco to attend his Seminary for Painting and Composition in 1955–56. For over a year Etrog lived at the well-known Israeli artists’ village Ein Hod and dedicated himself fully to art. His work was exhibited in several group shows in 1958, including The Art of Tomorrow at the Haifa Museum of Art, which brought together works by artists under thirty, and 10 Years of Israeli Painting at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, which involved more than 120 contributors. These public institutions also began to add Etrog’s work to their permanent collections; the Museum of Modern Art in Haifa bought the drawing Composition (Collage), n.d., and the Tel Aviv Museum of Art purchased Ladder of Surprise, 1955–57. Etrog’s former teacher Eugene Kolb purchased Requiem in Blue, n.d., for his private collection around the same time.

In December 1957, Etrog contacted Ralph Segalman, the executive director of the Jewish Federation of Waterbury, Connecticut (where Etrog’s aunt Rose was living), and asked for his help in securing a study grant in the United States or abroad. In February 1958, the Brooklyn Museum Art School offered Etrog a scholarship that would cover his tuition for the next academic year. Before departing for America, however, the artist opened his first solo show at the ZOA (Zionists of America) House in Tel Aviv. The exhibition received positive reviews in the Israeli press; critics took note of his works’ originality and emphasized their irregular shapes and their unique style, qualities that are well represented by Parade, 1954–56, the largest and most ambitious of Etrog’s early works. One reviewer enthusiastically claimed that the twenty-five-year-old Etrog was one of the most original painters of his generation, a true avant-garde artist rebelling against artistic conventions.

New York City and Toronto

Despite his high hopes, Etrog’s first year at the Brooklyn Museum Art School was “lonely and discouraging.” Although he was fascinated by the museum’s collection—he was especially drawn to its African and Oceanic art holdings, whose expressive shapes left their mark on his imagination—he didn’t find his place in the school. His course load was considerable and his limited English prevented him from engaging in the classes or making friends. New York’s high cost of living was challenging, and he could only afford to rent an abandoned fish shop with no heat or running water. To make ends meet, he had to work at an old-age home teaching Hebrew, giving art therapy classes, and supervising bingo games for a low salary and meals. His only support, emotional as well as financial, came from his aunt Rose and her family in Connecticut.

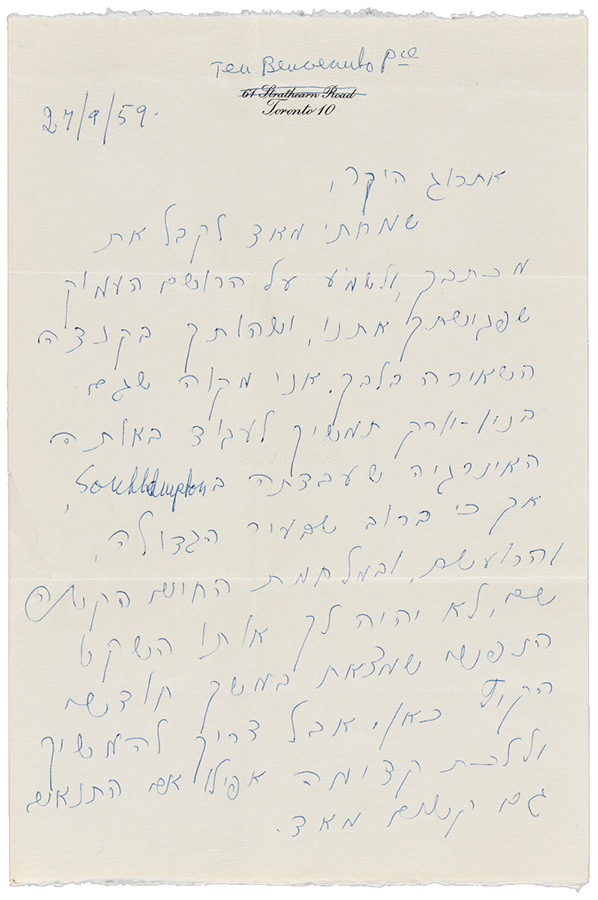

Etrog attempted without success to gain representation in New York during his first months in the city. However, in March 1959, he had a lucky break when he showed up at the gallery of Rose Fried (1896–1970) with several of his Painted Constructions. Although Fried was not immediately responsive to the works, the Jewish-Canadian businessman Sam (Samuel J.) Zacks (1904–1970) walked into the gallery while Etrog was there. Zacks, an ardent Zionist and strong supporter of Israel, and his Israeli-born wife, Ayala Zacks (1912–2011), were among Canada’s leading collectors of modern art. Zacks bought White Scaffolding, 1958, from Etrog on the spot for $200. Before returning to Toronto, Zacks saw more of Etrog’s works at the artist’s derelict studio; he was so impressed that he invited the young artist to visit him in Canada.

Etrog travelled to Canada for the first time in late June 1959. During this trip Zacks offered Etrog the opportunity to spend the rest of the summer at his Southampton home, 225 kilometres north of Toronto on Lake Huron. Among Zacks’s many businesses was a plywood factory near Southampton, where an artist could have access to materials and studio space. Etrog accepted the generous offer and spent two and a half months taking full advantage of the free materials, the power tools, and the peace of mind that came with his much-improved living conditions.

Etrog made his first Canadian sales to Sam and Ayala Zacks and, through them, to their collector friends. He soon gained representation at the newly established Gallery Moos in the Yorkville neighbourhood of Toronto, which specialized in positioning local artists in an international context, as well as in European art. The owner, Walter Moos (1926–2013), gave Etrog his first Canadian show, which opened on October 1, 1959. Even at this early stage of his career, Etrog involved himself in decisions about how his work would be promoted and contextualized. Moos felt that an exhibition catalogue would be an unnecessary extravagance; Etrog countered that he would pay for it out of his own pocket if need be and won the argument. H. Baer, reviewing the show, was full of praise for the show and wrote: “It happens sometimes but very rarely that an exhibition of painting is completely enthralling; proof that the artist achieved complete communication. Sorel Etrog is an example.”

The Launching of an Artist

Etrog returned to New York City in the fall of 1959 but quickly began his application to become a Canadian resident. After his successful Canadian summer, he could afford to rent a proper studio in Manhattan with the painter Edith Isaac-Rose (1929–2018) and to leave behind his part-time job to commit to his art full-time. He abandoned his Painted Constructions to devote himself to sculpture, while still regularly drawing and sketching, as he would throughout his life, both independent works as well as studies for sculptures that, at times, numbered in the hundreds for a single piece. He developed a new style of biomorphic works, sculptures that were inspired by living organisms and natural forms of growth, as well as by the art he had seen in the Oceanic collection of the Brooklyn Museum.

Etrog continued to hone his technical skills as a sculptor. He practised not only moulding in plaster but also set about learning the technical ins and outs of casting in bronze, specifically the multistage lost-wax process, at the Modern Art Foundry in New York. He would use bronze almost exclusively in his sculptures from that point on and took pride in his ability to command this labour-intensive process single-handedly.

The transition to a new medium and style yielded immediate successes. Gallery Moos gave Etrog a second exhibition in 1961, featuring works described as providing “almost endless visual delights in tensions and counterpuntals” that caught the attention of the important American art collector Joseph Hirshhorn (1899–1981). He immediately purchased eight sculptures. This sale was unprecedented in the Canadian art world at the time and was newsworthy enough to be reported in all the major Toronto papers. Etrog’s work began to be recognized internationally as well, in part thanks to Zacks’s connections and unwavering support. In 1961 the Guggenheim Museum in New York acquired Blossom, 1960–61, and in 1963, following Etrog’s first solo exhibition in New York, the Museum of Modern Art purchased Ritual Dancer, 1960–62. The Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo, the Netherlands, acquired Complexes of a Young Lady, 1962, also in 1963. All these works were inspired by the natural forms of trees, flowers, and other vegetation, and their acquisition by major institutions shows that Etrog’s personal artistic evolution was in step with a fascination in the wider art world with biomorphism.

Etrog received his Canadian residency status in 1962 but remained in New York until the following year to complete his studies. In 1963, before settling into a studio on the top floor of the former Tip Top Tailors building near Toronto’s waterfront, which was owned by his friends and future gallerists Yael and Ben Dunkelman, Etrog returned to Israel for the first time since 1958. He also travelled to Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, and France with his sister, Zipora, who went on with him to New York and Toronto afterward. In Florence he encountered Etruscan art for the first time. These ancient works would become the inspiration for what Etrog would name his Links period, during which both his sculptures and his paintings featured a motif of two elements connected by a loop.

Global Recognition

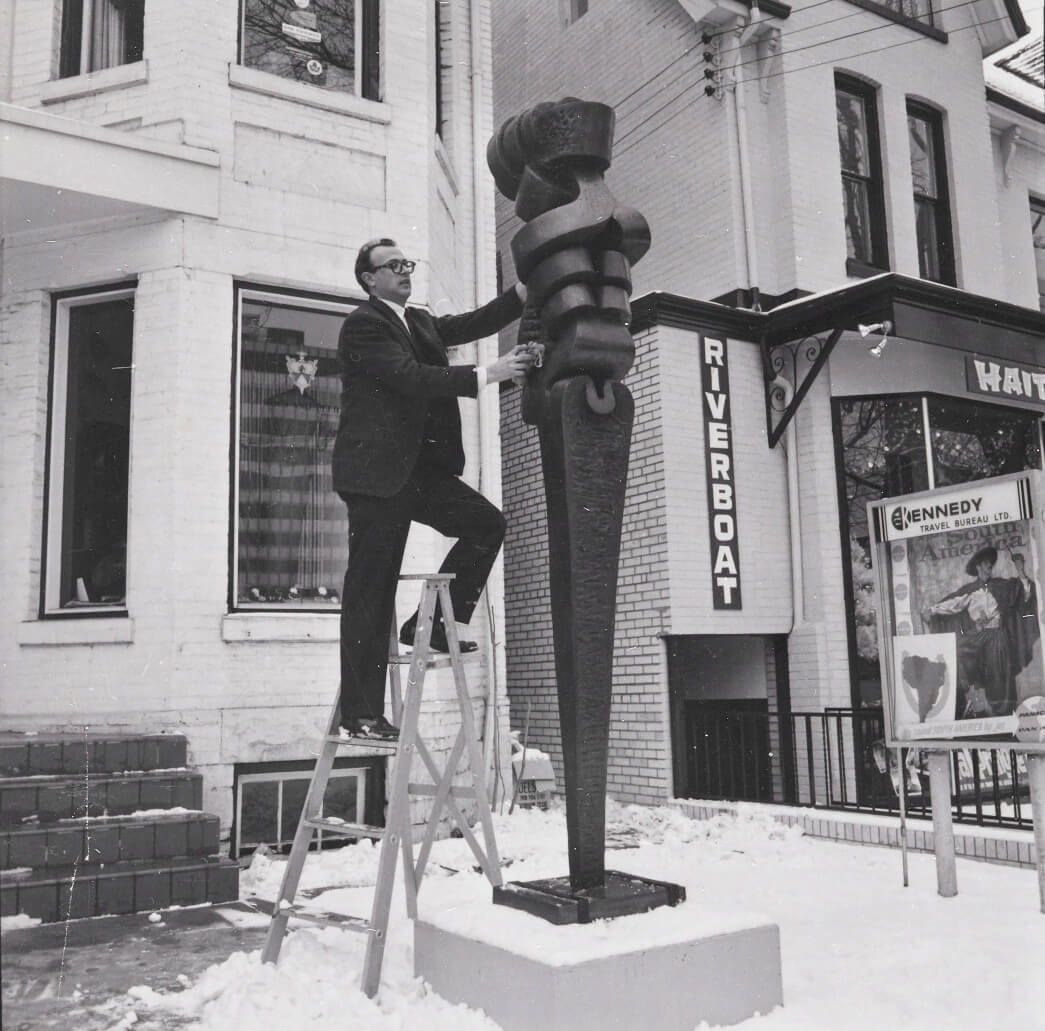

In 1965, Etrog had his first travelling exhibition, which opened at Gallery Moos in Toronto before moving to the Pierre Matisse Gallery in New York City, the Felix Landau Gallery in Los Angeles, and terminating at Montreal’s Galerie Dresdnère. This four-venue show garnered much attention in Toronto thanks to the inclusion of large-scale works, two of which—Mother and Child, 1960–62, and Capriccio, 1961–64—were about three metres in height and were installed outside Gallery Moos for the duration of the show, enlivening the Yorkville streetscape and announcing the exhibition to passersby. The Toronto art critic Barrie Hale shrewdly noted that the outdoor display, the choice of monumental works, and the four locations of the show were conscious strategies designed by Etrog and Moos to “enhance Etrog’s international reputation.”

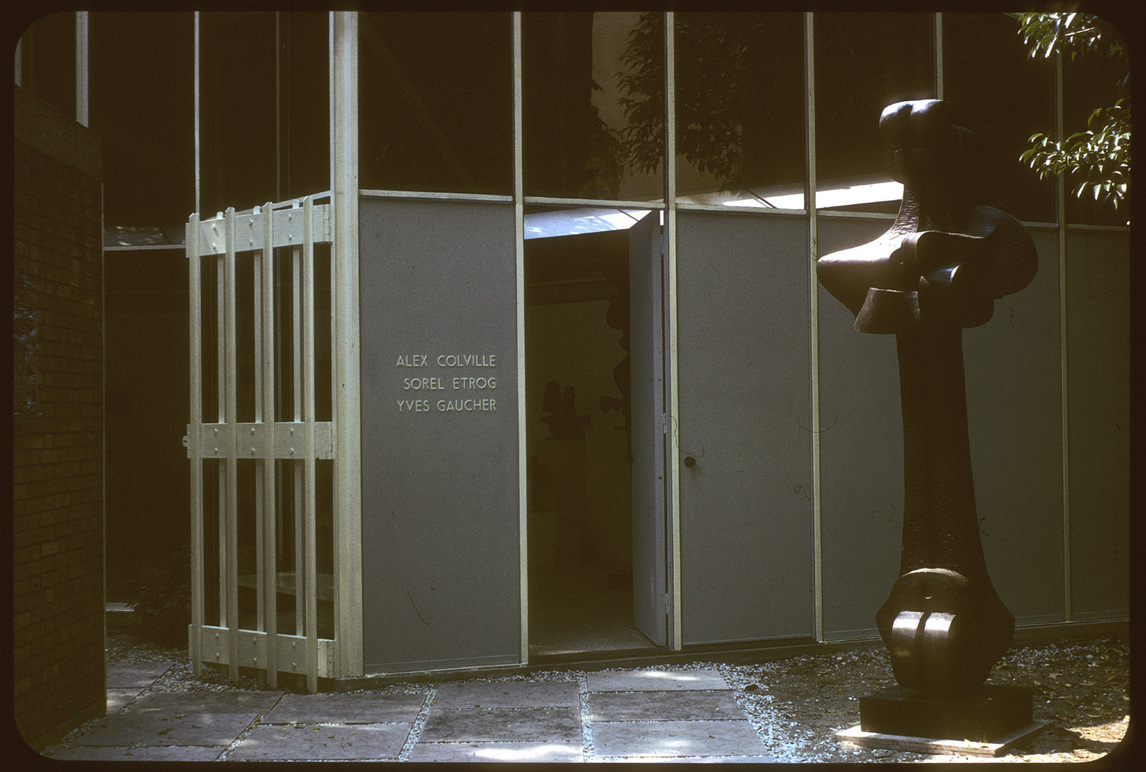

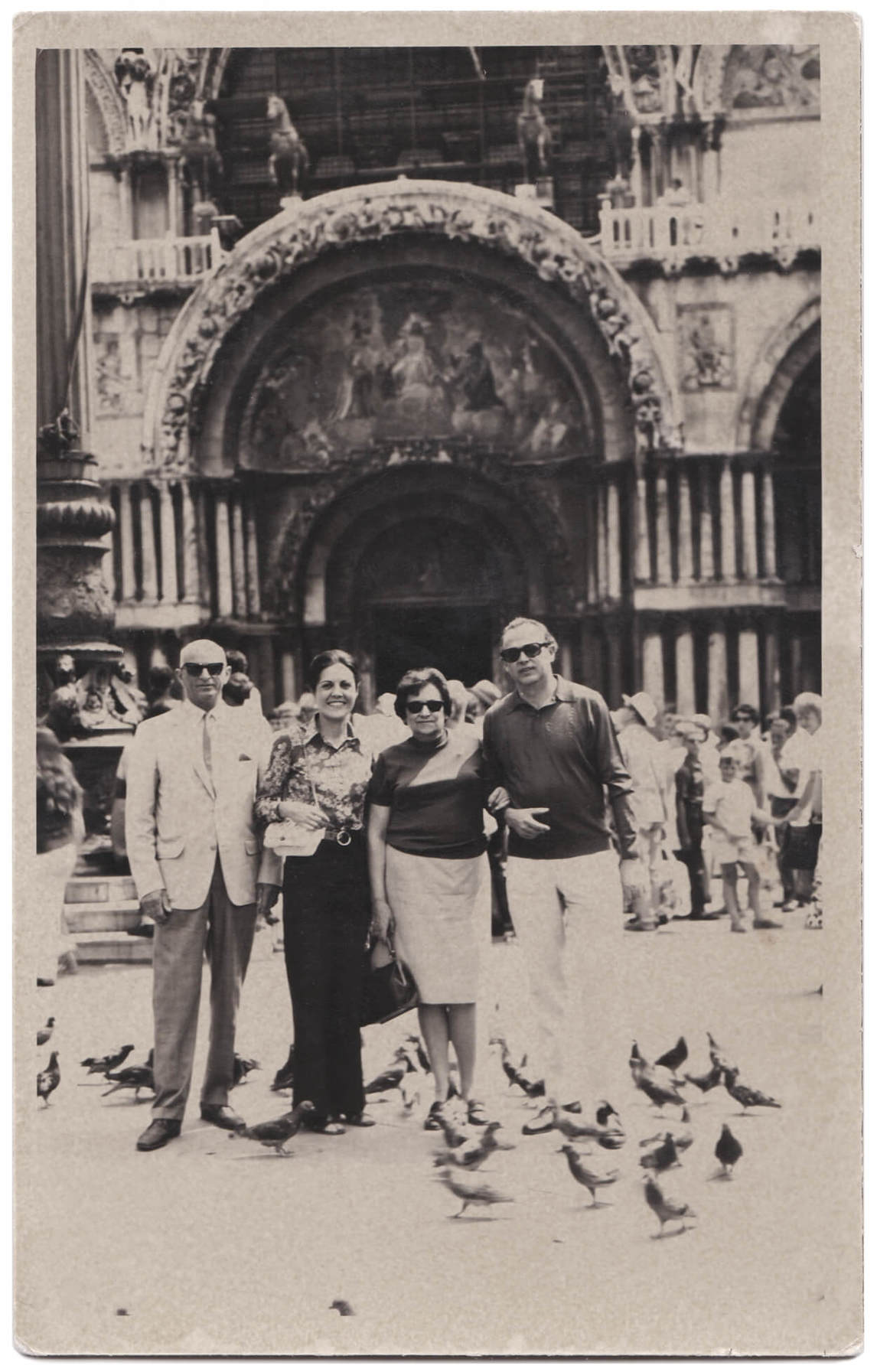

The strategy proved successful. In 1966, Etrog was chosen to represent Canada at the Venice Biennale—one of the most important exhibitions in the art world—along with two painters, Yves Gaucher (1934–2000) and Alex Colville (1920–2013). Initially Etrog wanted to exhibit graphic work as well as sculpture, but the Canadian Venice Biennale curator, Willem Blom, decided to focus solely on Etrog’s bronze sculpture with nineteen works from the artist’s brief yet already diverse career. These included the early, more abstract, War Remembrance II, 1960–61, and two large-scale sculptures, Mother and Child, 1960–62, and Moses, 1963–65, which were positioned outside the Canadian pavilion. After Venice, Etrog participated in Expo 67, Montreal’s hugely successful international fair, with Flight, 1963–64, and Moses. He returned home to Toronto and contributed two works to the city’s large outdoor sculpture exhibition Sculpture ’67. Today one of those sculptures, Survivors Are Not Heroes, 1967, is installed outside Hart House Gallery and is recognized as a local icon.

The Biennale enabled Etrog to fulfill a dream he had had since his 1963 trip to Italy—to spend long periods of time in Tuscany. In late 1965 he moved to Florence, where he rented both an apartment and a studio. He began casting his work at the renowned Michelucci Foundry in the nearby town of Pistoia, and this is where most of his sculptures would be cast into bronze for the remainder of his career. Living in Italy, Etrog was able to regularly visit his family in Israel. During one of those trips, he met his future wife, Lika Behar, a fashion designer, who soon moved with him to Italy.

Although this period was rich in accomplishments, Etrog also experienced considerable personal difficulties. In Florence he witnessed the 1966 flooding of the Arno River, which killed more than a hundred people and damaged many of the city’s historic monuments and art collections. The experience affected the artist tremendously, rekindling traumatic wartime memories. Then, in February 1967, he and Lika were involved in a life-threatening car accident. Lika suffered minor injuries, but Etrog—who was driving—broke both his legs and the middle finger of his right hand. The recovery, which involved multiple surgeries, took months. During this time Etrog became “discouraged and frustrated.” He left Italy, a place he had come to think of as his “second home,” shortly thereafter.

Back in Toronto, Etrog and Lika married and he rented a studio near the intersection of Yonge and Dundas Streets. In the early 1970s the city had a vibrant scene. The art collective General Idea (active 1969–1994) rented a studio nearby on Yonge Street and, in 1973, opened the artist-run centre Art Metropole. The painter Gershon Iskowitz (1919–1988) also had his working space some blocks west, near Spadina and Dundas, among many other artists who lived and worked downtown. But Etrog, then and throughout his life, sought the company most often of men and women of words—writers, philosophers, and academics—as was fitting for a voracious reader with an encyclopedic knowledge of philosophy, poetry, and literature and who collected a library to match.

In 1968, Etrog became a household name in Canada as the designer of the bronze statuette presented to winners at the Canadian Film Awards; it was known as the Etrog until it was renamed the Genie in 1980. A travelling exhibition titled One Decade was organized by Toronto’s Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) and toured to eleven venues throughout the province of Ontario from 1968 to 1970. It was considered, at least by the AGO’s director of education and extension, William C. Forsey, “to be the finest circulating exhibition in the Province.”

New Borders and Boundaries

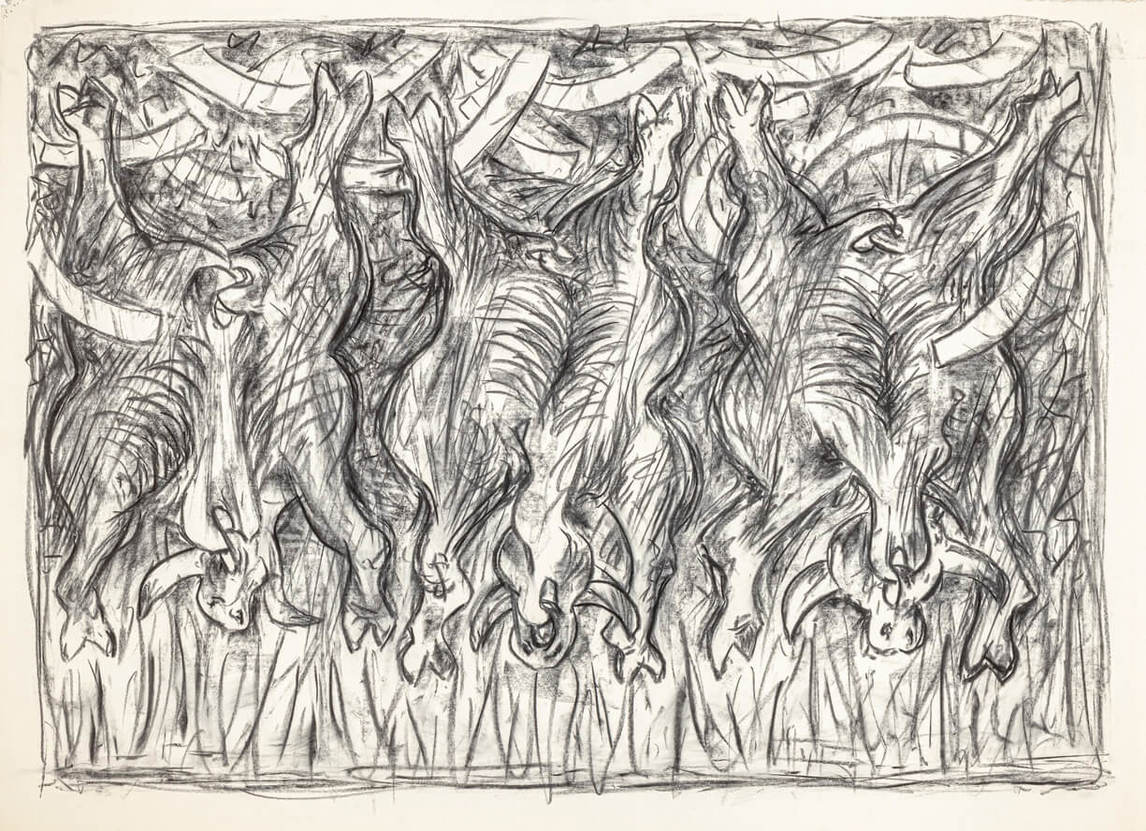

The injuries Etrog sustained in his 1967 car accident and the long recovery took their toll, and the artist experienced an episode of severe depression in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The result was a dark yet powerful period in his art, which he named the Bulls. During this time he made hundreds of black and white drawings depicting bulls in moments of terror, horror, and physical pain, as can be seen in Targets (Study after Guernica), 1969, his potent rendition of Pablo Picasso’s Guernica, 1937.

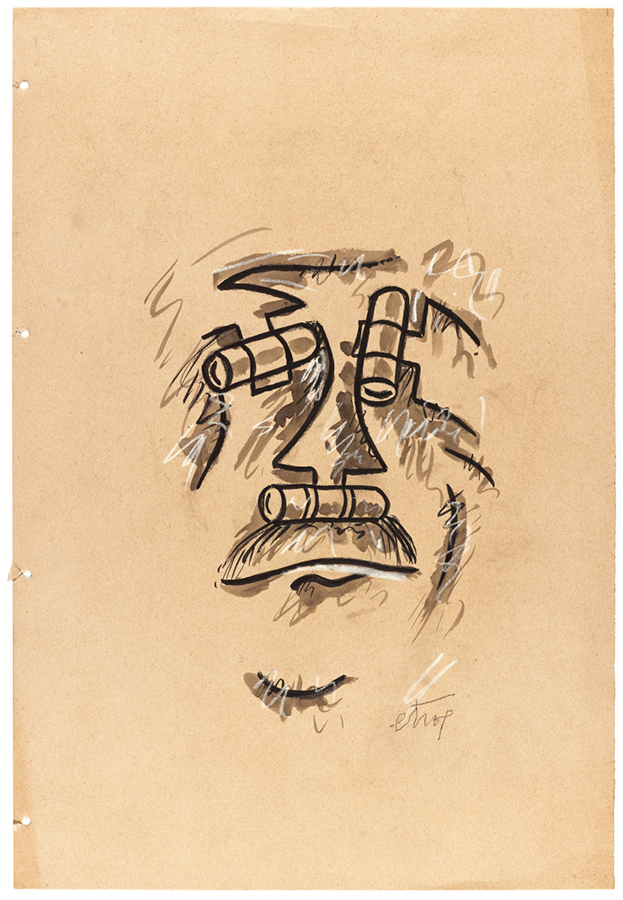

In 1968, as his injuries were still healing, Etrog returned to Italy and opened another studio in Florence where he found new positive energy, as is reflected in his transition from the dark Bulls works to his short-lived Screws and Bolts period. During this time the artist’s work was strongly influenced by Surrealist artists such as Jean Arp (1886–1966), Salvador Dalí (1904–1989), Man Ray (1890–1976), and Meret Oppenheim (1913–1985), and drew inspiration from a humble connecting device, the screw.

In Etrog’s next style, called Hinges, which lasted until 1979, the artist continued his exploration of oppositions. These works are characterized by an obvious tension—between movement and stasis—where the primary element of the sculpture, the hinge, is explored. Many of them, such as Rushman,1974–76, or Pieton, 1974, depict human figures whose body parts and joints are articulated through the mechanism and appear as if walking. He also created paintings using the motif, and even addressed it in a play that was never performed.

During the 1970s, Etrog became more adventurous in his experimentation and began to make artwork in media that he had not previously used. In 1974, he created the avant-garde film Spiral, which explores the human journey from birth to death. This film, which he wrote and directed, was screened on CBC television. It took on a second life when the media theorist Marshall McLuhan collaborated with Etrog on a book that pairs a collage of stills from the film with quotations by modernist writers. In 1978, Etrog designed sets and costumes for the play The Celtic Hero: Four Cuchulain Plays by W.B. Yeats, which premiered at the Bayview Playhouse Theatre in Toronto.

Around this same time, Etrog and his gallerist Walter Moos began to pursue public sculptural projects, and his work was commissioned or purchased by large private companies to adorn their offices and headquarters. He developed a relationship with the architect Boris Zerafa, of the firm Webb Zerafa Menkes Housden, who, in 1975, selected two existing works by Etrog for their Bow Valley Square project in Calgary. Five years later, three additional Etrogs were installed there, two purchased by the developers of Bow Valley Square, Hammerson Canada, the third on loan from Gallery Moos. Zerafa encouraged Etrog to participate in an international contest to design a sculpture for the Sun Life Insurance Corporation’s Toronto headquarters, which his company designed, in the late 1970s. Etrog won the contest and was commissioned to create the iconic Sun Life (completed in 1984), a work whose size pushed the artist to incorporate steel into his work in addition to his usual bronze.

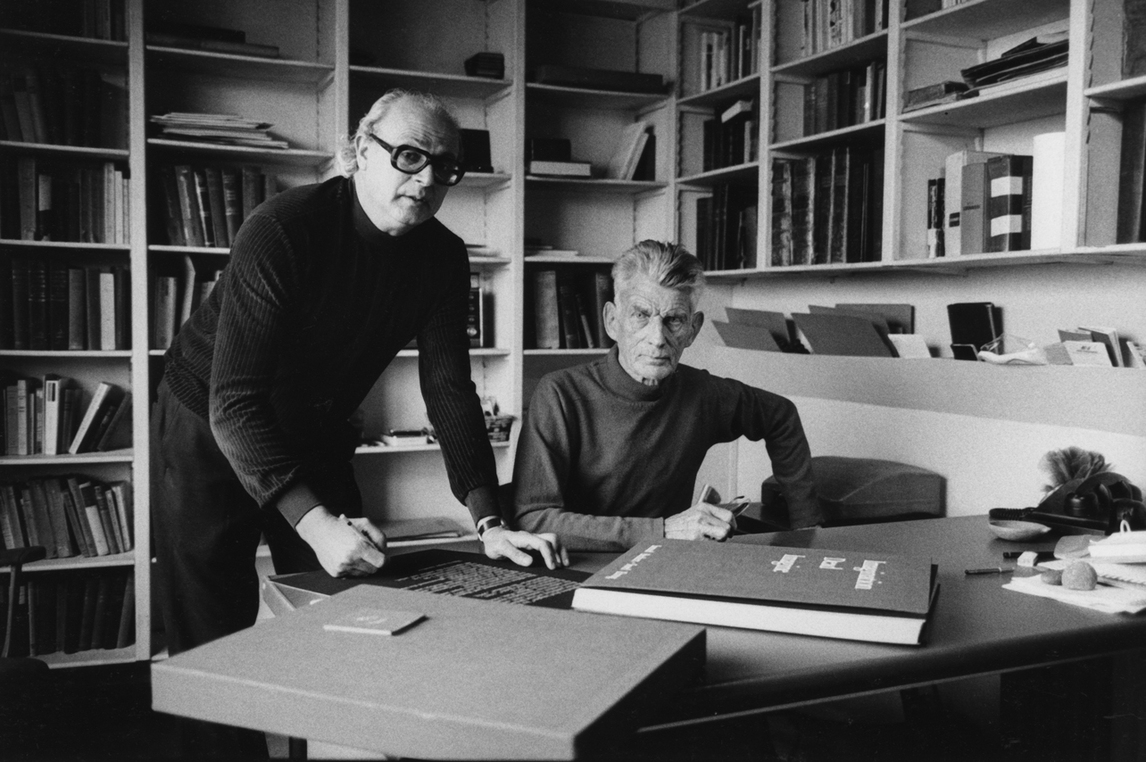

The early 1980s were years of change as well as of continued creative experimentation for the artist. In 1980, Etrog and his wife, Lika, divorced, and the artist opened a studio in Paris, where he worked for two years while still maintaining his Toronto studio, now housed in a building at Yonge and Eglinton owned by his close friend and patron the developer Al Green. He curated two exhibitions in Toronto: a group show of twenty-five contemporary Canadian sculptors of large-scale work at the Guild Inn Park in 1982 and the 1984 exhibition of Sam Zacks’s own paintings—the collector was also an artist—at the Art Gallery of York University, for which Etrog also designed the catalogue, wrote an introductory text, and planned the opening event. His friendship with Samuel Beckett (1906–1989), whom he had met in 1969, gave rise to two collaborative projects during this time. In 1982, Etrog designed and illustrated the limited-edition artist book Imagination Dead Imagine, based on a text by Beckett, and in 1984 he created, performed, choreographed, and even composed the electronic music for a performance piece titled The Bodifestation of the Kite in celebration of the Irish writer’s birthday.

The decade ended with the monumental commission Powersoul, which Etrog created for the 1988 Summer Olympics in Seoul, South Korea. At ten metres tall, this steel construction—stylistically a part of his Hinge period, but using a new material necessitated by his desire to produce works on an even greater scale—is Etrog’s largest work.

Last Years and Legacy Building

Although the 1990s brought accolades for Etrog—he was named a Member of the Order of Canada in 1995 and a Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres of France in 1996—it also marked the beginning of a decline in his health and energy. The artist, who had devoted his life to art and was noted for his productivity and innovation, was troubled by his diminishing ability to work and grew reclusive.

In September 1996, Etrog returned to Romania, his country of birth, for the first time in forty-six years. He and his friend the Canadian publisher Howard Aster were invited to participate in a Radio Romania International conference in Bucharest. During this visit a discussion began regarding an Etrog retrospective in the country of his birth. Etrog returned the following year, but the retrospective never came to fruition. These trips affected him greatly. While he didn’t return to his hometown of Iaşi, Etrog spoke about his shock when he discovered that, of the 112 synagogues that once served its thriving Jewish community, only two were left.

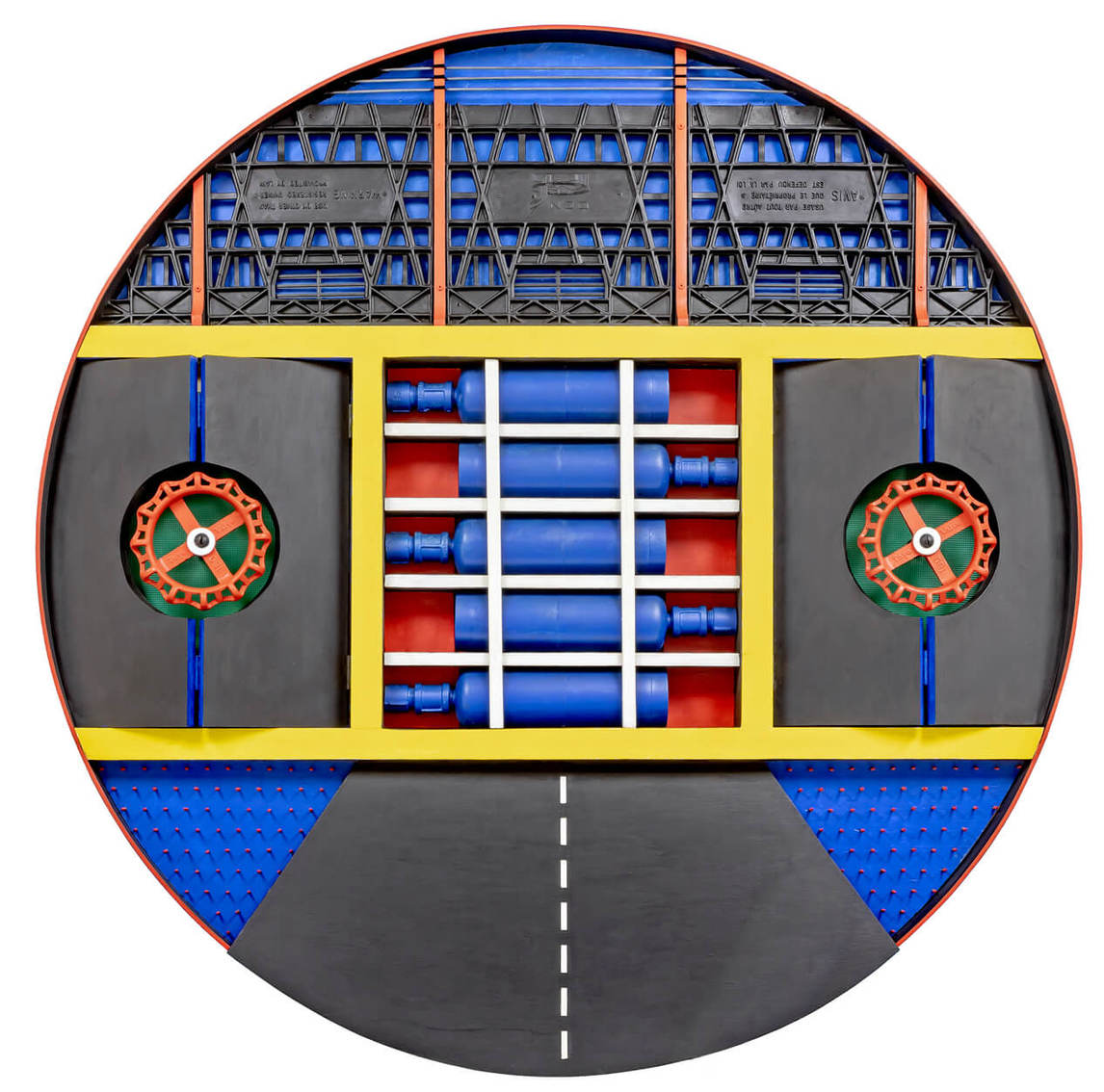

Following his Romanian travels, the artist experienced his last burst of creativity in a series he called the Composites, assemblages made from wood and found materials such as milk crates, nails, and light bulbs. Although their bright colours and geometric shapes might appear to echo the abstraction of Etrog’s early Painted Constructions, closer examination reveals that they are filled with references to concentration camps, trains, and gas chambers—reflecting the trauma of his childhood memories rekindled by his return to Romania.

The 2000s saw celebrations of Etrog’s work, especially thanks to his Vancouver gallery, Buschlen Mowatt, which held a retrospective in 2003; a show celebrating his early constructions in 2006; and an exhibition in 2008 of his Links paintings, which was filled with works that had never before been exhibited. In 2005, Etrog represented Canada in the inaugural Vancouver Biennale and was awarded a Lifetime Achievement Award by the Biennale Board of Directors.

In his final years, Etrog began to concentrate on the legacy of his life’s work and where it would be housed. He engaged in conversations regarding the creation of a sculpture centre or a museum where his art could be seen and understood in context. Several locations for such a place were considered, including Vancouver’s Simon Fraser University (which had mounted the 2008 exhibition of the Link paintings), the UJA Federation of Greater Toronto’s campus, and Art-St-Urban, in St-Urban, Lucerne, Switzerland. However, none of these options was ultimately chosen.

After Etrog broke his hip and entered Toronto’s Mount Sinai Hospital in October 2010, he began to envision the creation of a gallery inside the hospital where his artwork would be displayed and patients could find solace. He soon mentioned this idea to Lawrence Bloomberg, then Chair of Mount Sinai Hospital, who set up a meeting between Etrog and collectors Jay and Barbara Hennick. While meeting with them Etrog offered to donate a substantial amount of work, intended to show “his gratitude to the people of Toronto and Canada for allowing him to pursue his lifelong passion for art.” Etrog’s vision was fully realized in 2016 with the inauguration of the Hennick Family Wellness Gallery, where sculptures and paintings are on permanent display. Today, the gallery is one of the largest single collections of the artist’s work.

The year 2010 also saw the first steps toward an Etrog retrospective at the AGO, including discussions regarding housing his papers in the gallery’s archives, where they are found today. The retrospective, the final exhibition to be held during Etrog’s lifetime, opened in April 2013 and coincided with his eightieth birthday. A few months later he would be hospitalized again. During his last days, he reminisced about his time in New York City and wondered about what might have been had he stayed. Sorel Etrog passed away on February 26, 2014.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements