With her ability to work both in the academic realist style and with a more painterly Impressionist approach, Sophie Pemberton satisfied her own inclinations even as she catered to the tastes of her clients. Her earliest portraits follow her formal training, and those painted between 1903 and 1925 include both styles, yet in each they capture the individuality of the sitters and suggest a story. The oil landscapes she created between 1903 and 1926 all reveal the influence of Impressionism. They demonstrate her versatility as she pared down detail and moved away from standard representations toward modernism, painting what she saw and revealing how she felt. In her decorative art during the 1920s, she returned to a polished academic style with invisible brush strokes and precise detail.

An Early Interest in Portraiture

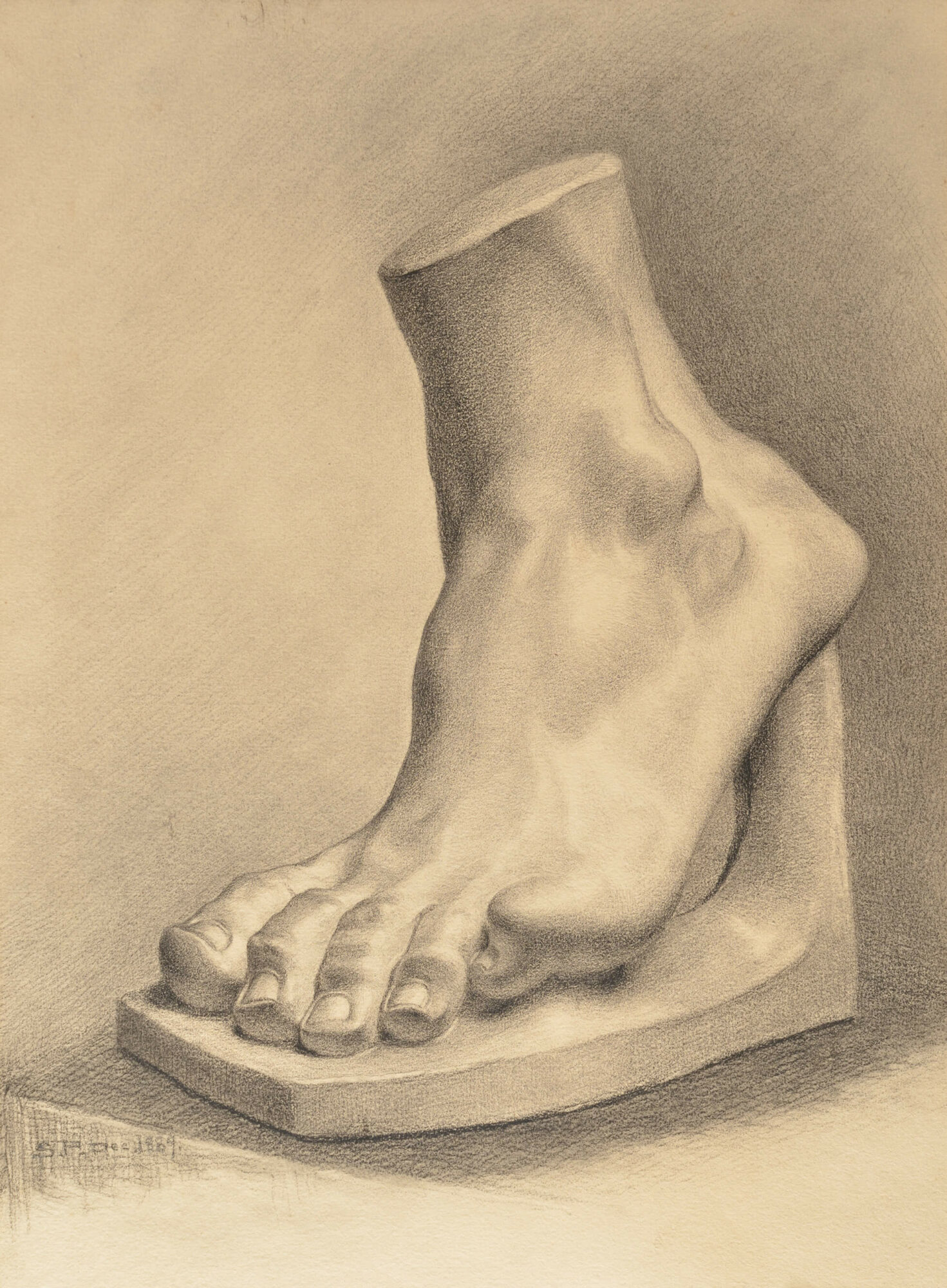

Pemberton decided to become a professional portrait painter when she was about twenty years old. To fulfill that goal, she studied in three art schools in London, each of which followed the academic syllabus of the South Kensington Schools. Students began by drawing two-dimensional prints or engravings of Old Master compositions in pencil or chalk until they had learned to model accurately with lines and strokes. They then moved to drawing three-dimensional objects, including plaster casts of various body parts, reproductions of Greco-Roman and Renaissance works such as Michelangelo’s David, and original antique statues in the galleries. Pemberton’s Drawing of a plaster cast foot, 1889, and Venus de Medici, c.1890, created while at Cope’s School, reveal her use of chiaroscuro and tonal ranges to achieve three-dimensionality. Anatomical studies were part of the training, as demonstrated by her Anatomical Practise, Cope’s School, 1889–90, with the parts labelled.

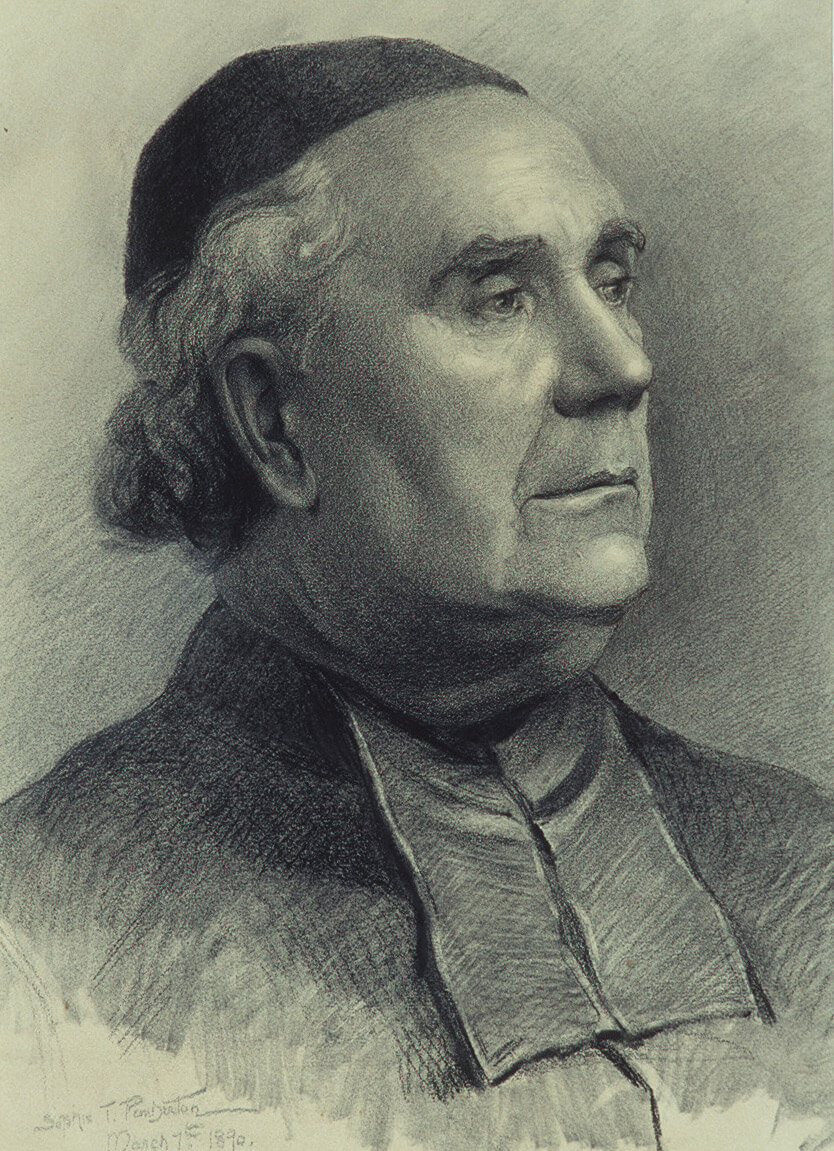

Pemberton soon advanced to the drawing from life classes, where models held poses for a set time while the students drew them, usually with charcoal. In Portrait of a Cardinal, 1890, she skilfully used shading to create volume and indicate the play of light on the figure.

Concurrently, Pemberton enrolled in oil-painting classes, where she learned how to prime the canvas, create an underdrawing, and layer and blend thinned paints that allowed her to work with smooth transitions and invisible brush strokes—the hallmark of the academic realist style as exemplified by the Académie Française and followed throughout Europe. The goal was naturalistic representation and accuracy of detail. In Plaster Cast, c.1890, Pemberton reworked earlier sketches of her Venus de Medici, rendering the plaster in monotone and adding a cluster of erythroniums (fawn lilies) in the foreground to obscure the breasts of the statue and soften the transition to the stand.

With Mansi – An Italian, 1892, Pemberton, now at the Clapham School of Art, built on her sketches from the life class to create a realistic portrait with almost invisible brush strokes. The face is illuminated, the eyes and lips animated, while a shadow delineates the soft curve of the jaw. The clothing, in contrast, recedes into the background.

While in Victoria in 1895, Pemberton painted a series of realistic, three-quarter-view portraits—of her mother, Theresa Pemberton, and a few as commissions, such as Benjamin William Pearse. Two years later, when she returned to London and lived independently in her studio, she quickly entered her prime with the highly praised and widely exhibited Daffodils, 1897, and Un Livre Ouvert, 1900. She also began to experiment, first with Little Boy Blue, 1897, painted en plein air where she could capture the effects of sunlight on the scene. She painted in the “French style,” as one newspaper commented, adopting some of the techniques of the Impressionists such as Henri Matisse (1869–1954), who had deliberately changed the expectations of artistic style. Eschewing detail, she worked with short, visible brush strokes and often unmixed colours. She continued broadening her oeuvre with genre scenes of people at work: Winding Yarns, 1898, “an extremely capable piece of character delineation,” and Tarring Ropes, 1899/1900. The figures in these paintings are compelling and have stories to tell. Pemberton’s emphasis in her portraits was still to reveal the character of her sitters, but she was now providing context too, in the hope of attracting a wider audience.

Once at the Académie Julian in Paris (1898–1900), Pemberton reverted to the academic style for Bibi la Purée,1900. From here on, though, she varied her style depending on the client’s expectations and her own inspiration or the situation. The matching full-figure pair of Warren and Armine, both 1901/02, Colonel Schletter, 1910, and Peasant Woman, 1903, are painted in different styles, yet in each portrait it is the faces that draw the eye. When Pemberton painted her second husband, Horace Deane-Drummond, 1925, she portrayed him with dignified demeanour—no doubt as he desired.

A Move to Landscape

In Pemberton’s social class, the ability to draw and paint in watercolour was considered a pleasant recreation. Pemberton began lessons in her day school in Victoria and continued at the boarding school in Brighton, England. She and her friends enjoyed going on sketching excursions around Victoria and Vancouver equipped with portable easels and art supplies.

When Pemberton returned home in 1900 after her studies at the Académie Julian and an evening class with James McNeill Whistler (1834–1903), she was again interested in watercolour painting and enjoyed sketching days with Josephine Crease (1864–1947) and other friends. Sketching Picnic, 1902, reveals her technique. First, she blocked out the scene in pencil; then, with a wet brush, she applied watercolour washes to delineate the tones; finally, with a dry brush, she added the details of figures and trees and highlighted occasional outlines. In View over Victoria, c.1902, she used a wet application of paint, allowing colours to spread and blend in a way that blurred the panoramic view and was Impressionist in its result.

Pemberton’s earliest extant British Columbia oil landscape, Cowichan Valley, 1891, is a bucolic but unsophisticated view of a small pond with overhanging trees, grassy banks, and split-rail fences, featuring a Chinese boy and geese at the pond’s edge. Twelve years later in Brittany and Italy, a more experienced Pemberton began to work outdoors in oil consistently and to establish her own style. She was inspired by Barbizon painters’ reverence for nature, which they painted for its own sake, not as an idealized background to figures, and the more recent Impressionists’ focus on spontaneity rather than precision.

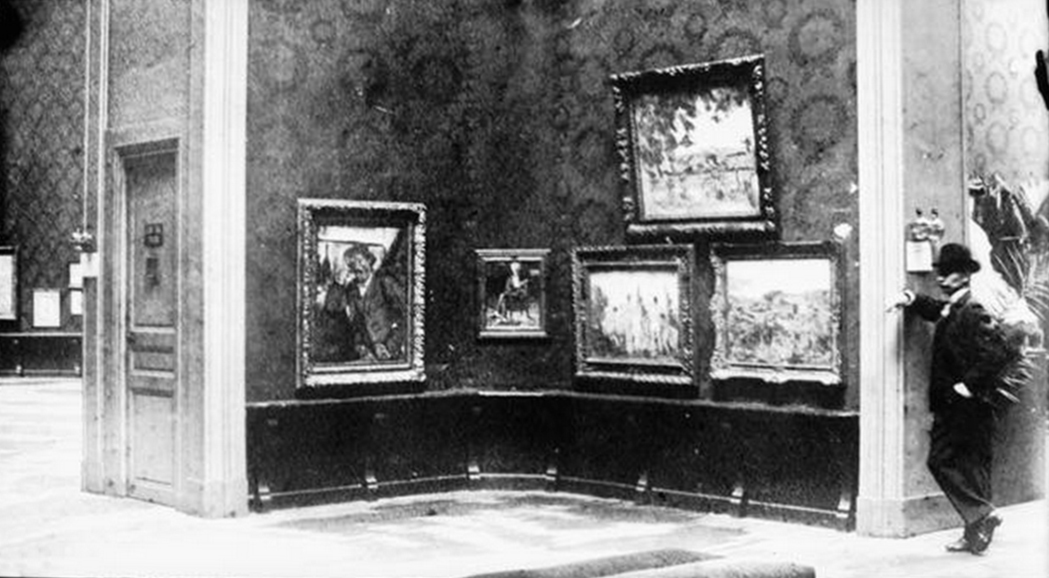

After several years in England and France, Pemberton had enjoyed ample opportunity to note the rising importance of various landscape genres. She viewed them in gallery exhibitions where she lived and travelled, appreciating artists such as Camille Pissarro (1830–1903) and Claude Monet (1840–1926) and, after 1903, modernist artists exhibiting landscapes at the newly formed Salon d’Automne. She also discussed their works and ideas with friends in her artistic community in both countries.

Pemberton now painted in oil outdoors without preliminary sketches, experiencing nature as she created the finished painting. She liked the wildness and slightly disorderly aesthetic in Dieppe Farmyard, 1903. At Caudebec-en-Caux she worked with a palette emphasizing the silvery greys she saw in the skies and in the smoothly flowing river, as in The Seine, 1903. She painted the built environment—the eclectic layering of dilapidated structures against the skies that produced shadowy contrasts. In both Caudebec-en-Caux, 1903, and Market place at Caudebec-en-Caux, 1903, she retained the freedom to suggest rather than delineate detail.

This outdoor work gave Pemberton the confidence to branch out from portraiture into landscape and urban scenes, though, unlike her portraits, she called them all “sketches,” possibly because they were not worked up in the studio. When she returned to British Columbia early in 1904, she continued to paint outdoors in oil, but readjusted to a more pellucid light, again favouring the blues of the ocean and spring camas flowers and greens of the forest, as she had done earlier in watercolour. This palette—in Mosquito Island, 1907, and A Prosperous Settler, 1908—was strikingly different from the colours she had favoured in Europe.

Just as she had revealed her personal feelings in Time and Eternity, 1908, she again veered toward Post-Impressionism in Weald Church, Kent, 1915. The image is not so much about the church as her delight in natural forms—the tree branches and the wildflowers swaying in the wind, the blossoms blooming in the crisp spring air. Pemberton had advanced her art once again.

Pemberton’s oil landscapes and outdoor scenes are often paired down in detail and have a painterly quality. Some reviewers saw them as preliminary sketches or unfinished works, yet they are serious studies in a deliberately different style as Pemberton sought to capture a moment, an impression. In 1908 a reporter in Victoria, equating realism with perfection, wrote: “In portraits she displays not only talent but thorough training and technique, and one may unhesitatingly call her a finished artist. Her work in landscapes shows that she is yet a student… whose possibilities are far from being exhausted.” Similarly, some of the English critics misunderstood her exhibit at the Doré Gallery in 1909: “As a landscape artist, she is entirely self-taught, and has developed her own style as a student of nature upon the Pacific Coast.”

Pemberton varied her technique, but did not discard her previous ways. In some Impressionist-style paintings she employed bold lines, thickly applied blocks of colour, and carefully crafted details, while in others she strove for luminosity and almost invisible brush strokes. La Napoule Bay, 1926, and Driveway of Moulton Combe, Oak Bay, 1921, reveal this versatility as Pemberton, confident in her skill, channelled her emotions through her art.

Botanical Paintings

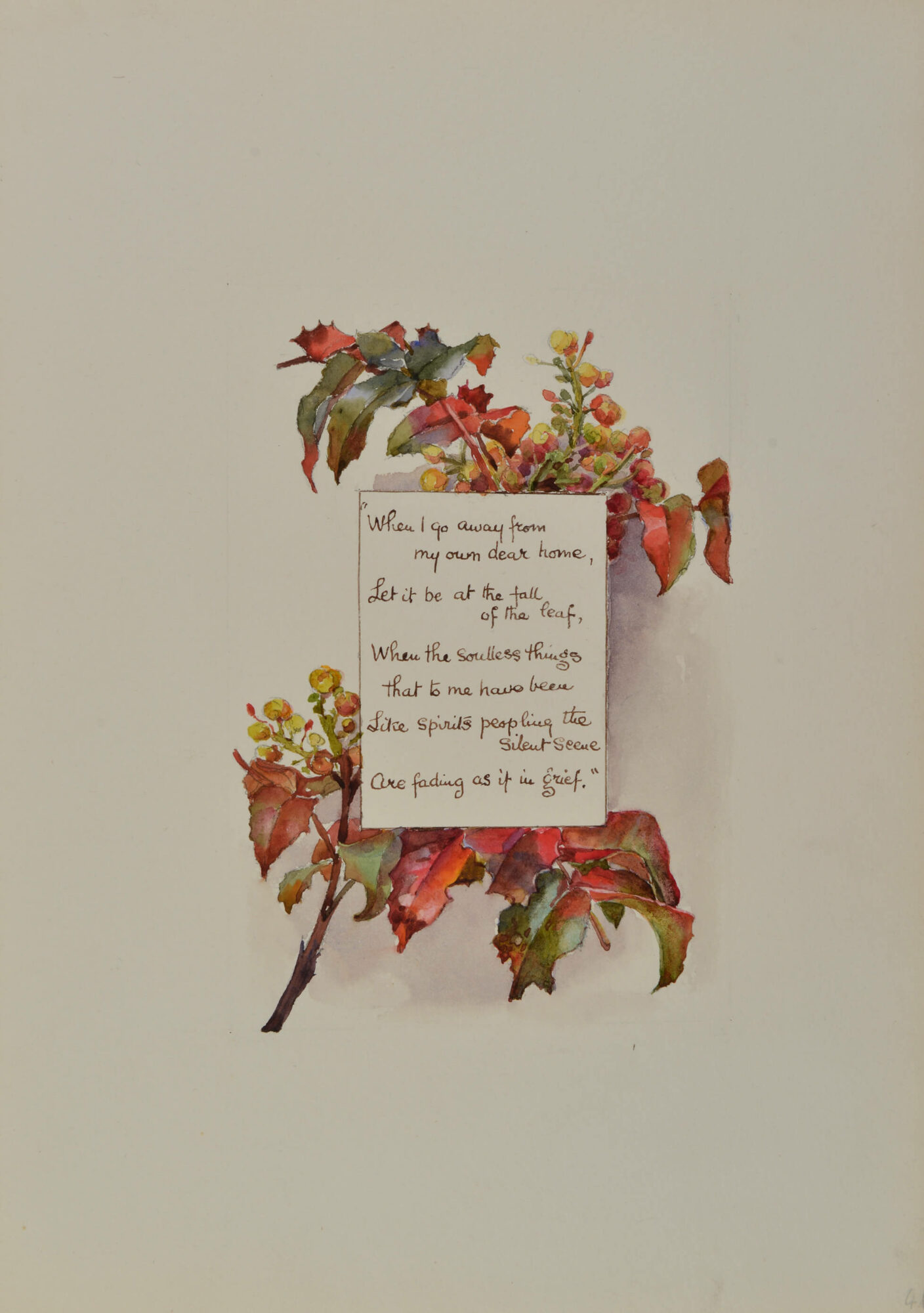

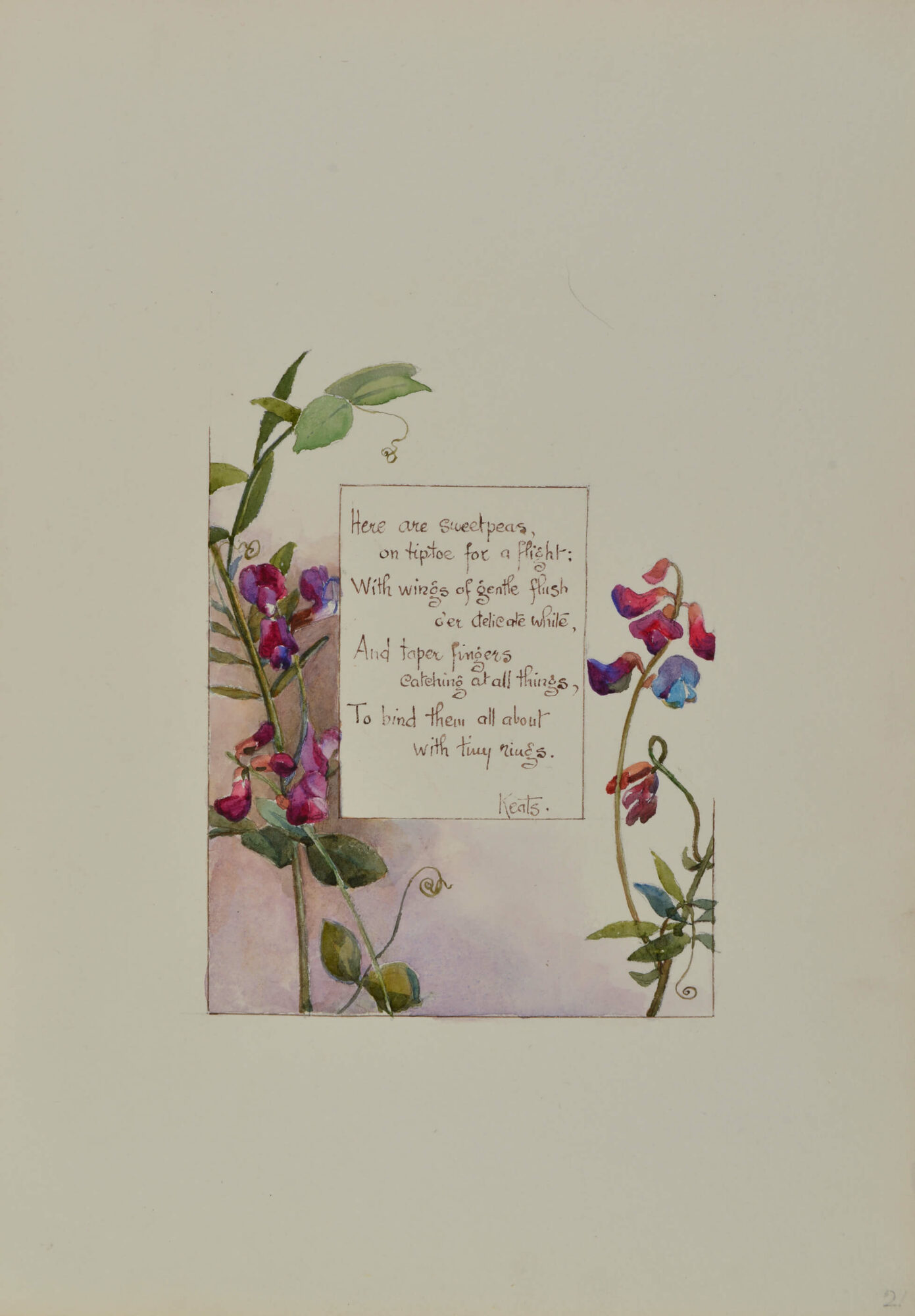

In 1895, while in Victoria, Pemberton painted two major series of botanical subjects in watercolour, including local wildflowers and cultivated domestic perennials. She presented her brother Fred with “An Affectionate Souvenir,” an unbound portfolio of forty-three sheets, each containing a single specimen that Pemberton paired with a handwritten verse from writers ranging from Shakespeare to Tennyson. She also gave her sister Ada a botanical portfolio of thirty-three unbound sheets. Both Fred and Ada were avid gardeners, so the gifts were thoughtful and appropriate. The portfolios served as souvenirs of Pemberton’s sojourns in Victoria between stints at art school.

Pemberton painted several other botanical specimens in 1900 and again in 1902 while in Victoria, but she seems not to have produced similar studies in England or abroad. It was a short-lived occupation for her: the only long-standing result was Pemberton’s special affinity for erythroniums (fawn lilies), a local wildflower that, in later life, she often sketched in the margins of her letters.

Kristina Huneault suggests that the close study involved to capture the delicate flowers may have been a meditation on identity, not unlike portraiture that “focused on exactitude of likeness and oriented toward viewer recognition. While portraiture traditionally allies identity and interiority… botanical art focuses on surface morphology… a portraitist seeks to capture an individual, the botanical artist… depicts those qualities most typical of a species group.”

Pemberton may have been introduced to botanical drawing and painting in 1882 in Victoria at the Reformed Episcopal School under Emily Henrietta Woods (1852–1916), who taught art there and who also contributed a watercolour floral bouquet in the album presented to Princess Louise. Over two decades, Woods created more than two hundred life-size botanical illustrations of wildflowers she observed, each titled with its scientific name. This endeavour may have motivated Pemberton during her Victoria hiatuses from art school.

Decorative Art

When Pemberton was overwhelmed by family tragedies and a long convalescence during the First World War, her neighbour Victoria Sackville-West (whose daughter, Vita, was affiliated with the Bloomsbury Group) persuaded her to use her artist’s skills on small, stress-free endeavours in decorative art. Sackville-West sold some of these objects at Spealls, her London shop, one of several boutiques opened by wealthy women whose personal taste dictated the inventory. There was a prevailing artistic interest in bridging the division between fine art and decorative art. As one example, the Omega Workshops (1913–19), a design enterprise founded by members of the Bloomsbury Group, offered decorative pieces that incorporated modernist principles, including painted furniture, tiles, and ceramics.

An eccentric and flamboyant woman, Sackville-West soon had Pemberton painting on glassware and wooden furniture and designing decorative detailing for lampshades and screens. Much of this work was destined for Sackville-West’s Knole House and, later, for her Brighton residence. Pemberton recorded entries in her diary such as “Painted 2 trays easy leaf design—glass dishes, the green ribbon,” and “Finished the shelves for VS.” Occasionally the diaries also include small sketches or notes of colour combinations. Sackville-West’s diaries provide her perspective: “Sophie came yesterday afternoon and we began painting furniture for Vita & Harold’s room…. The ground is blue and we decorate it with splashes of colours, encircled in gold lines…. We did 2 ‘Pedestals’ and one chest of Drawers today.” Pemberton received compensation for her labour. Notoriously thrifty, Sackville-West sometimes paid her in books from the Knole library or with other treasured objects, including a Persian rug.

From 1918 through 1947, Pemberton parlayed her decorative work into private commissions and raising money for charity. Most popular of all were tea trays, which she painted with delicate gold filigree patterns alongside chinoiserie-style images of birds, insects, and bouquets of garden flowers, often taking inspiration from and copying the oil paintings of imaginative sixteenth-century Flemish painters. Pemberton was inspired in this form of decoration—painting over and lacquering furniture and smaller pieces—in part by the Victorian black papier-mâché furniture inlaid with mother of pearl that had been popular in her youth.

Pemberton was always busy, as she expanded her practice to include large pieces of furniture such as desks and interior décor. In 1921 she created a Persian theme for a new haute couture shop in Victoria and, at home at Wickhurst Manor, she transformed rooms with floor-to-ceiling paintings. “One room… was painted to simulate a Persian garden in deep rich colours of blue and red,” and the bathroom became an immersive summer garden of delphiniums. Baroque-style immersive interiors that created a total environment were fashionable between the wars, incorporating “pleasurable shocks” and playful “momentary deceptions of trompe l’oeil.”

In one diary entry Pemberton described her methodology: “We went to the March’s Goddendene Farnborough—Cooper & Co. Greek St Soho aniline dyes all colours 1 oz mix with methylated spirits for plaster tinting or shellac.” Unfortunately, when Wickhurst Manor was sold, the new owner “announced her intention of having the [principal bed]room redecorated in a more conventional style.”

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements