Paintings by Sophie Pemberton were well received in English and Canadian exhibitions and the media. Their success brought the isolated province of British Columbia into focus both overseas and in central Canada. Family support enabled Pemberton to train at prestigious academies in London and Paris and to live independently in her own studio. Community support in turn brought her portrait commissions and frequent reviews in the local press. Although a strong feminist, she was torn between her professional ambitions and her family obligations. This tension thwarted her career in midlife, especially after she suffered a serious accident and turned to painting decorative objects. It is only in recent years that her significance in Canadian art has been reevaluated.

British Columbia Art, 1870–1950

In 1869 Pemberton was born into a frontier society situated within more populous Indigenous territories. The gold rushes of the 1860s had swelled the economy and the mixed population in this predominantly British society, but British Columbia became a province only in 1871, with Victoria as the capital. The Canadian Pacific Railway finally connected to Vancouver in 1887. Victoria, on Vancouver Island, boasting a modest population of 16,841 in the 1891 census, was even more isolated, both from developments in Vancouver but especially from the much larger urban centres of Montreal, Halifax, and Toronto.

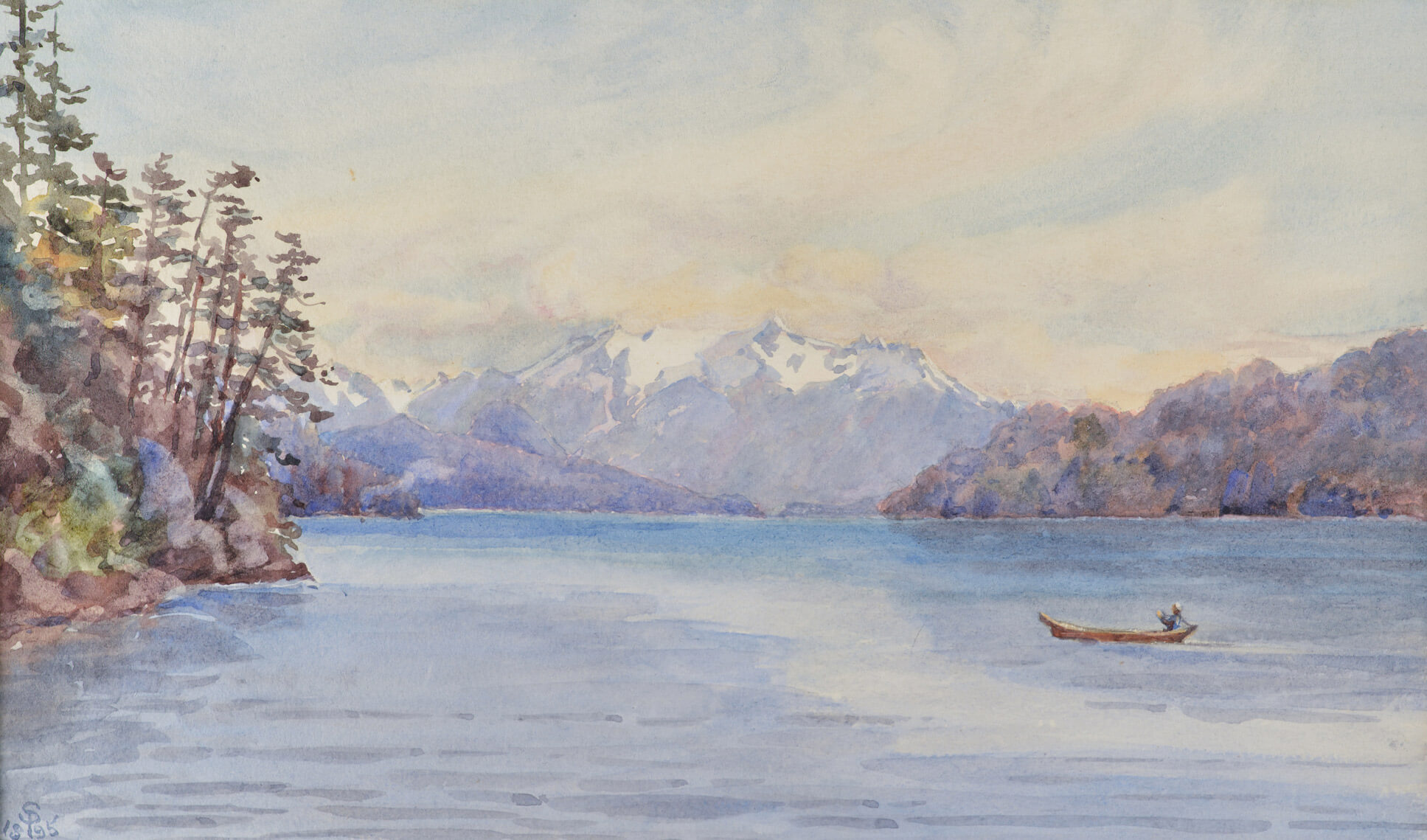

Although Victoria citizens supported music, theatre, and other cultural pursuits, the visual arts lagged behind. A few local matriarchs such as Sarah Crease encouraged artistic endeavours; topographic artists among British naval officers stationed at Esquimalt, including Edward Parker Bedwell (1828–1882), painted watercolour landscapes; and visiting professionals such as Georgina (1848–1930) and Constant (1842–1910) de l’Aubinière offered group classes. In general, though, as one observer commented, “Artists come to the city, but do not remain.”

In this environment, without any art schools, serious young artists had no choice but to go to England, France, or San Francisco for training. Pemberton and her friends Josephine (1864–1947) and Susan (1855–1947) Crease enrolled in art schools in London in 1889; Emily Carr (1871–1945) left for San Francisco in 1890; and Theresa Wylde (1870–1949) travelled to London around 1892. The published comments of a well-connected expatriate Englishman, Clive Phillips-Wolley, allude to Pemberton being a casualty of Victoria’s backwater mentality: “A Victorian artist, native born… had her picture hung in the [Royal] Academy [of Arts] and [Paris] Salon before it was known that she painted in British Columbia.”

Abroad, Pemberton helped to raise the profile of Canadian art, as some exhibition catalogues listed her Canadian residence and reviewers described her as a “colonial artist.” She presented an idea of Canada to her international friends. Within Canada, her visibility in exhibitions organized by the Art Association of Montreal and the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts reminded Canadians in the easterly provinces that artistic talent could herald from the distant West Coast.

It was not until 1909, when the Island Arts Club (later the Island Arts and Crafts Society) was established, that a formal organization for artists and exhibitions existed in Victoria. A branch of the Federation of Canadian Artists formed in the 1940s organized art shows in temporary facilities—including exhibiting a selection of works loaned by Pemberton family members in 1947 and 1949. Only in 1951, when the population of Greater Victoria reached 100,000, did the city have a permanent art gallery, the Victoria Arts Centre. In 1954 paintings by Pemberton and Carr featured in a joint exhibition there.

Family and Community Support

Fortunately, Pemberton’s prosperous and socially prominent family supported her ambitions to be a professional artist—an uncommon and difficult goal for women at this time. Leisured women were encouraged to sketch or paint as a pastime but not as a serious pursuit. Pemberton received rudimentary instruction at the private girls’ school she attended. A school certificate in her scrapbook documents her “honourable mention” in painting; she won “a prize for some pretty drawings” at the local agricultural fair in the “under 12” category; and in 1882 two of her watercolour landscapes, Fire in the Forest and View from Gonzales, were included in “A Souvenir of Victoria” album presented to the visiting Princess Louise.

Pemberton’s parents supported her ambitions from the start. In 1893, when they heard her first-class results in the South Kensington examinations, her father wrote: “Your splendid success brought new life to us all & this being a small place it is already the topic everywhere.” He provided key moral and financial assistance that gave her confidence and, in his will, a generous allowance that enabled her to continue her art studies, rent a studio, and travel. Emily Carr, in contrast, had to fund her English sojourn through savings she earned teaching art.

On news of Joseph Pemberton’s sudden death on November 11, 1893, the family immediately rallied to support Pemberton, who was living with other women art students in Alexandra House. In England, her brother Joe received the news first. “Mr Coggin… told me last night of the sad occurrence & this morning I went over to Sophie to break the news as quietly as possible, & then brought her over to Finchley with me.” Valiantly she continued, but grief soon overwhelmed her. By the new year, she was in distress, and a friend from Victoria who was in England alerted the family that she was homesick, heartsick, and suffering from strange physical symptoms. In March they decided to intervene. “My Mother and sisters are leaving for England tonight,” wrote Fred. “Their departure of course has been hurried by the bad news about Sophie.”

In addition to this strong family support, every time Pemberton returned home for a visit the local newspapers updated her status, such as the Victoria Daily Times commenting in June 1900 that “Miss Sophie Pemberton has returned to ‘Gonzales’…. [She] is an enthusiastic art student and her work has attracted much favorable comment in London and Paris.” Three years prior, a Vancouver newspaper had also sung her praises:

Those of us who take any interest in anything but dollars and mining shares are delighted by the news…. Miss Sophia Pemberton has fulfilled some of the promise of her childhood… a large picture by her… has been awarded an honourable position in Room 1 at the Royal Academy’s Exhibition of pictures in London.

Independence, however, required more than financial support. Pemberton studied in London more than a decade before Helen McNicoll (1879–1915) and, as Samantha Burton, Susan Butlin, and Kristina Huneault have written, gender barriers for both artists held strong. In 1889, when Pemberton enrolled at the school run by Arthur Cope (1857–1940), many notable art schools, associations, and clubs remained closed to women. By 1895, female students at most London art schools still attended separate classes. The Royal Academy of Arts was a male preserve where women were denied membership but, with jury approval, could exhibit. In France, the École des beaux-arts admitted women only in 1897. When Pemberton began at Académie Julian in 1898, the owner’s wife, Amélie Beaury-Saurel (1849–1924), managed the separate women’s atelier even though most of the classes were integrated.

Social strictures discouraged women from moving freely in public spaces. Whether travelling by rail across Canada, aboard ship on the Atlantic, on excursions to the Continent, or simply to visit galleries, Pemberton was accompanied by a female companion. As her father instructed: “If you prefer an early return, you will have to exert yourself, to find an escort to prevail on.” Likewise, living alone bordered on the scandalous unless women found a small female-run boarding house in an appropriate neighbourhood—as Carr did in England. Decidedly more upscale was Alexandra House, founded for female art and music students, where Pemberton and the Crease sisters all resided while attending classes in London.

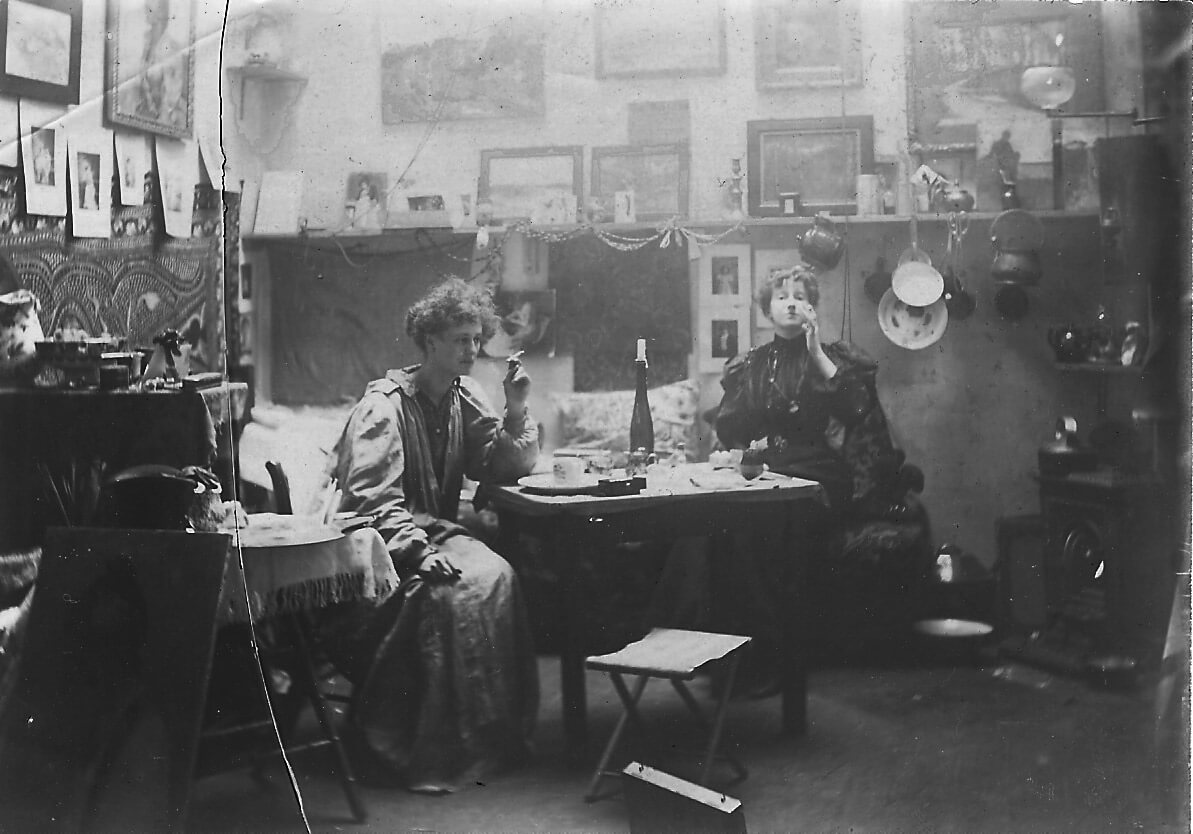

When Pemberton began living independently in Stanley Studios, a building constructed for artists, she boldly defied the social norm that obliged single women to safeguard their reputations. The candid photograph of her female friends in her studio provides rare insight into the private freedom residents there enjoyed. On the eve of her marriage, Pemberton wrote nostalgically: “I’m a little bit sad thinking those beautiful bohemian times are gone.”

Female Friendships

In this male-centric art world, women forged their way through informal personal relationships and participation in clubs for women. Pemberton made friends at the art schools she attended in London and Paris and at the Stanley Studios. She also kept in touch with many women she met in England or France who were active in the arts. In 1914, for instance, she reconnected with her close friend from the 1890s, Constance Gore-Booth (1868–1927).

Several older women became mentors and friends for life. The Swedish artist Anna Nordgren (1847–1916) shepherded Pemberton through the exhibition application process in the 1890s, accompanied her to sketch in Brittany, supported her membership in the 91 Art Club, and, in 1910, visited Pemberton at Wickhurst before they travelled to Paris for the Salon. Amélie Beaury-Saurel kept a protective eye over her at the Académie Julian and chaperoned her during many painting sessions with Bibi la Purée. In turn, Pemberton invited Beaury-Saurel to her wedding to Canon Arthur Beanlands in 1905.

When Pemberton was overcome by the deaths of family members and a serious accident between 1916 and 1919, her neighbour Victoria Sackville-West at Knole House cajoled her into resuming her creative pursuits on a smaller scale, including painting trays and other domestic items. Sackville-West opened the door to her many influential female friends who were patrons of the arts. “To Knole,” Pemberton wrote in just one of many examples, “painted balls, Mdm la Contesse d’Avignon & her daughter came to tea & Sir E. Lutyens.”

Although documentation is lacking, it is tempting to think that several of the expatriate Canadian women artists also influenced each other. Florence Carlyle (1864–1923), Sydney Strickland Tully (1860–1911), and Emily Carr were in London at the same time as Pemberton; Tully lived at Stanley Studios and, in The Twilight of Life, 1894, used the same model as Pemberton did shortly after. Like Tully, Pemberton enrolled at Académie Julian, and, like Carlyle, she studied under Benjamin Constant (1845–1902) and J.P. Laurens (1838–1921). Pemberton arrived in Paris while Laura Muntz (1860–1930) and Mary Riter (1867–1954) were still there, and it is possible that the closely dated paintings of Breton women by Pemberton, Riter, and Carlyle indicate common sketching opportunities. Muntz, Pemberton, and Riter exhibited at the Paris Salon; and Muntz, Tully, Carlyle, and Pemberton were selected for the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in 1904 and the Royal Academy of Arts in 1909.

-

LEFT: Sydney Strickland Tully, The Twilight of Life, 1894

Oil on canvas, 91.8 x 71.5 cm

Art Gallery of Ontario, TorontoRIGHT: Sophie Pemberton, Portrait of a Woman, 1896

Oil on canvas, 76.5 x 56 cm

Private collection -

Sophie Pemberton, Untitled (Breton Woman), 1896

Oil on canvas, 34.3 x 28.5 cm

Private collection -

Florence Carlyle, Mère Adèle, 1897

Oil on canvas, 36 x 26.7 cm

Museum London -

Mary Riter Hamilton, Easter Morning, La Petite Penitente, Brittany, c.1900

Oil on canvas, 117.4 x 82.2 cm

Winnipeg Art Gallery

Pemberton and Women’s Suffrage

Like Helen McNicoll, Pemberton benefited from membership in women’s art organizations and joined several suffragist and feminist groups. The 91 Art Club provided a safe space for female artists in London and networking opportunities. Pemberton, along with most of the women at the Stanley Studios, including Sydney Strickland Tully, exhibited there. She most likely also joined the Women’s International Art Club, formed in Paris in 1898, which organized a large exhibit in London in 1900 to assert “the claim of women to be admitted within the innermost circles of the profession.”

Pemberton’s commitment to the cause of women’s rights became more public after she and Beanlands moved to Sevenoaks in Kent and she agreed to represent the local organization. Over the years, she joined several women’s clubs in London—the Sesame Club (est. 1895), the Lyceum Club (est. 1903), and the Pioneer Club (est. 1892)—enabling further networking for her art and advocacy for social change.

As a strong-minded and committed artist who believed in and actively pursued the rights of women, Pemberton’s life appears contradictory. She boldly moved to England in 1895 and, over the next decade, pursued her art career with impressive presentations at major exhibitions there and in France. But various maladies interfered, requiring her to withdraw from a concentrated push toward establishing a fully professional career. We cannot know whether these bouts were psychosomatic as well as physical, but she did live a long and full life.

Pemberton was a dutiful daughter, torn between her intended profession and the traditional familial expectations that unmarried daughters were responsible for aging parents. Her widowed mother wanted her daughters to remain in her orbit and, as executor of her husband’s estate, she controlled the purse strings. Pemberton compromised her career because of family obligations demanding extensive travel and frequent houseguests. Her situation was not uncommon: both Mary Riter and Laura Muntz abruptly returned from overseas to tend to ailing family members. “What is the use of being strongminded,” Pemberton wrote, “if you can’t control yr own conscience?”

As Pemberton and Muntz soon discovered, in a tightly gendered society, the social obligations of marriage restricted their professional careers as they lost their freedom to paint with single-minded purpose. Domesticity was clearly expected to be the priority for upper-middle-class women. As the spouse of a cleric, Pemberton had to participate in numerous social obligations. In a rare candid letter from 1905, she confessed to mixed feelings about her upcoming marriage:

I am engaged to a canon. But this is no ordinary clergyman. He is charming, older than me, but very childish in some very literary and therefore very artistic ways. He is now thinking of an atelier that he will add to his house…. But it’s awful how I have to change. You have to pay visits, check in, and be useful, and worst of all receive visits…. But I am not scared because I love him with all my heart.

Penumbra, 1907, may have been Pemberton’s visualization of her post-marriage situation. As the title suggests, the figure is between light and shade, awaiting the return of the sun.

Reputation and Legacy

Pemberton has been described as the first artist from British Columbia to receive international professional distinction. She was one of only a handful of Canadian women artists overseas during the 1890s, and her prestigious exhibition record remains admirable, both for her time and as a woman artist working within an overtly male preserve. Her relative obscurity in Canada, during her lifetime and since, stems from life choices she made as dictated by social expectations or financial worries, her long residency in England, and serious health issues that interrupted her professional trajectory and removed her from public view.

Equally responsible for Pemberton’s invisibility was the isolated position of British Columbia in relation to the art scene in central and eastern Canada and to the site of major art exhibitions. One Victoria reporter suggested in 1954 that the “lack of full recognition has evidently been due to a number of factors, among which has been our traditional disbelief in the viability of our native talent.” These same observations applied to another Victoria artist, Emily Carr, during the first five decades of her life. Pemberton, moreover, kept many of her artworks and bequeathed them to family members, meaning that they have been exhibited only infrequently.

Despite Pemberton’s success in winning the Prix Julian and the Julian-Smith awards in Paris and her decade of prestigious exhibitions and positive reviews, vestiges of gendered bias in defining the term “professional artist” have also limited her reputation over the last hundred years. The standard interpretation has been that she ceased to be a serious artist after her marriage. Her exhibition record belies this view, although health issues played a significant role.

Pemberton’s change in surname after both her marriages contributed to her loss of public identity. For instance, Penumbra, 1907 (at the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts in 1907), and both Memories, c.1909, and The Amber Window at Knole, 1915 (at the Royal Academy of Arts in 1910 and 1916, respectively), all bore the surname Beanlands—as did a number of landscapes she painted for her solo exhibition at the Doré Gallery in London. La Napoule Bay, 1926, which sold through a private gallery, was signed S.D. Drummond. In addition, Pemberton’s focus on interior decorative objects after her health crisis in 1916–18 may well have suggested to some that she had switched to a frivolous pursuit. Yet she never relinquished identifying as an artist. On her return to Canada in 1949, at the age of eighty, she listed her occupation as “artist.”

Our current understanding of Pemberton’s oeuvre and life has been shaped by three retrospective exhibitions—at the Vancouver Art Gallery (1954) and the Art Gallery of Victoria (1967 and 1978). Each one traced her career until 1904 and exhibited paintings held by Pemberton family members and those donated to both galleries and the British Columbia government. Since then, only a few of these works have appeared in exhibitions of Impressionism or Canadian women artists. Many significant canvases Pemberton painted and exhibited during her fifty years overseas have not yet been located, probably because they sold to private purchasers.

The retrospective exhibition that opened in the fall of 2023 at the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria included many works held in private collections that have not been seen in the past century. It reintroduced Pemberton to her home town and situated her achievements within the context of her times, providing an opportunity to reevaluate her work and to reassess her career as a Canadian artist of merit.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements