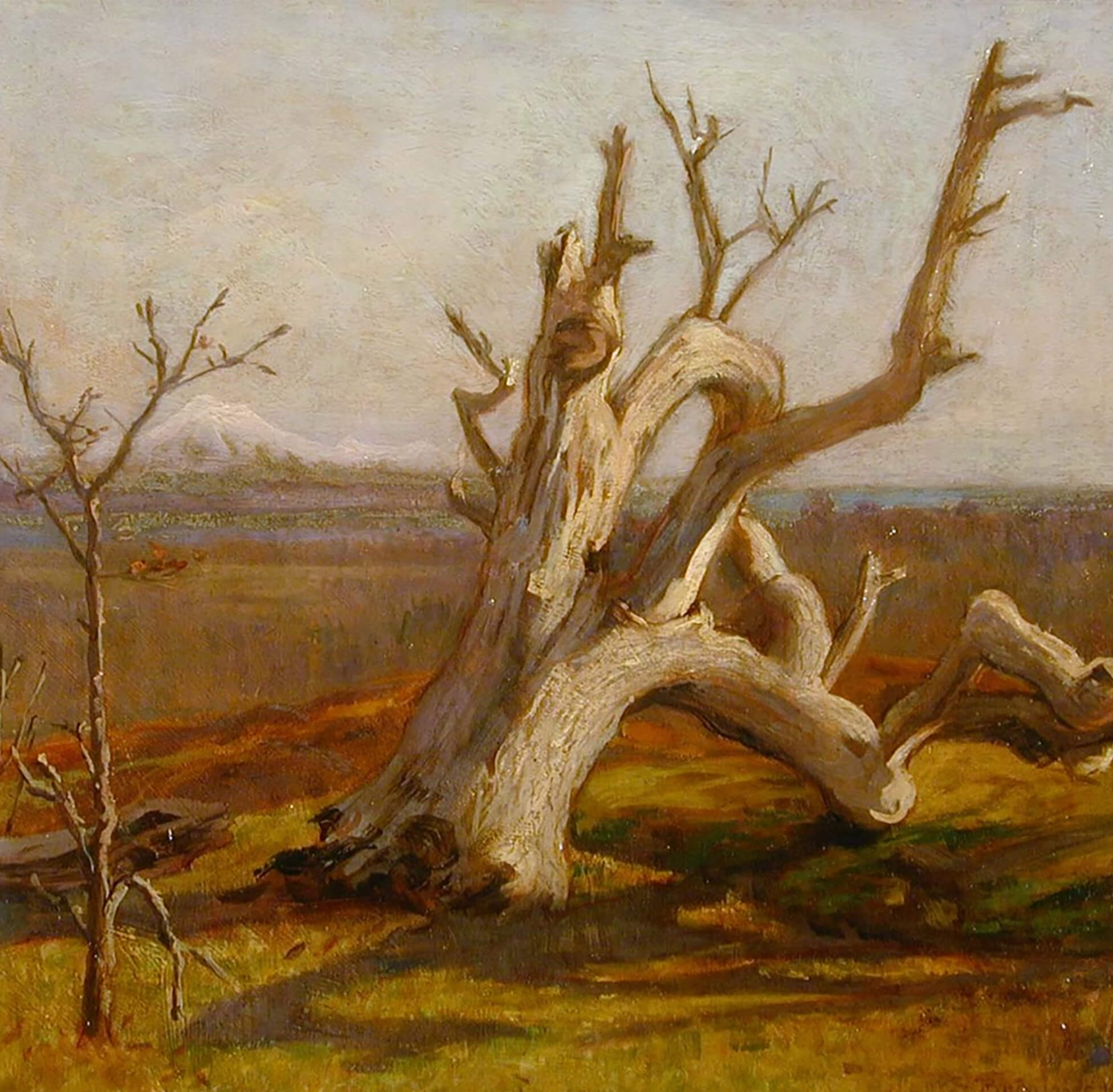

Time and Eternity 1908

Sophie Pemberton, Time and Eternity, 1908

Oil on canvas, 37 x 39 cm

Art Gallery of Greater Victoria

Pemberton painted this canvas on a chill winter’s day from a prominent Victoria hilltop. Although observers might have expected a classic view of Mount Baker, she delivered it with a substantial twist. The mountain is visible in the distance beyond the forested stretch of land and the small islands beneath her viewpoint, but it is not the focus of her composition. Instead, she profiles the twisted remnant of a long dead Garry oak tree, of desolate and almost war-torn character. To the immediate left springs a Garry oak sapling, identifiable by one last desiccated brown leaf, which has grown from an acorn provided years earlier by the now decaying tree.

The title speaks to regeneration, of new life alongside old, but also of the enduring snow-clad mountain. Time is the life cycle of the tree. Eternity, the dormant volcano Mount Baker, is a constant presence, in contrast to the finite existence of Garry oaks that change visibly over the years.

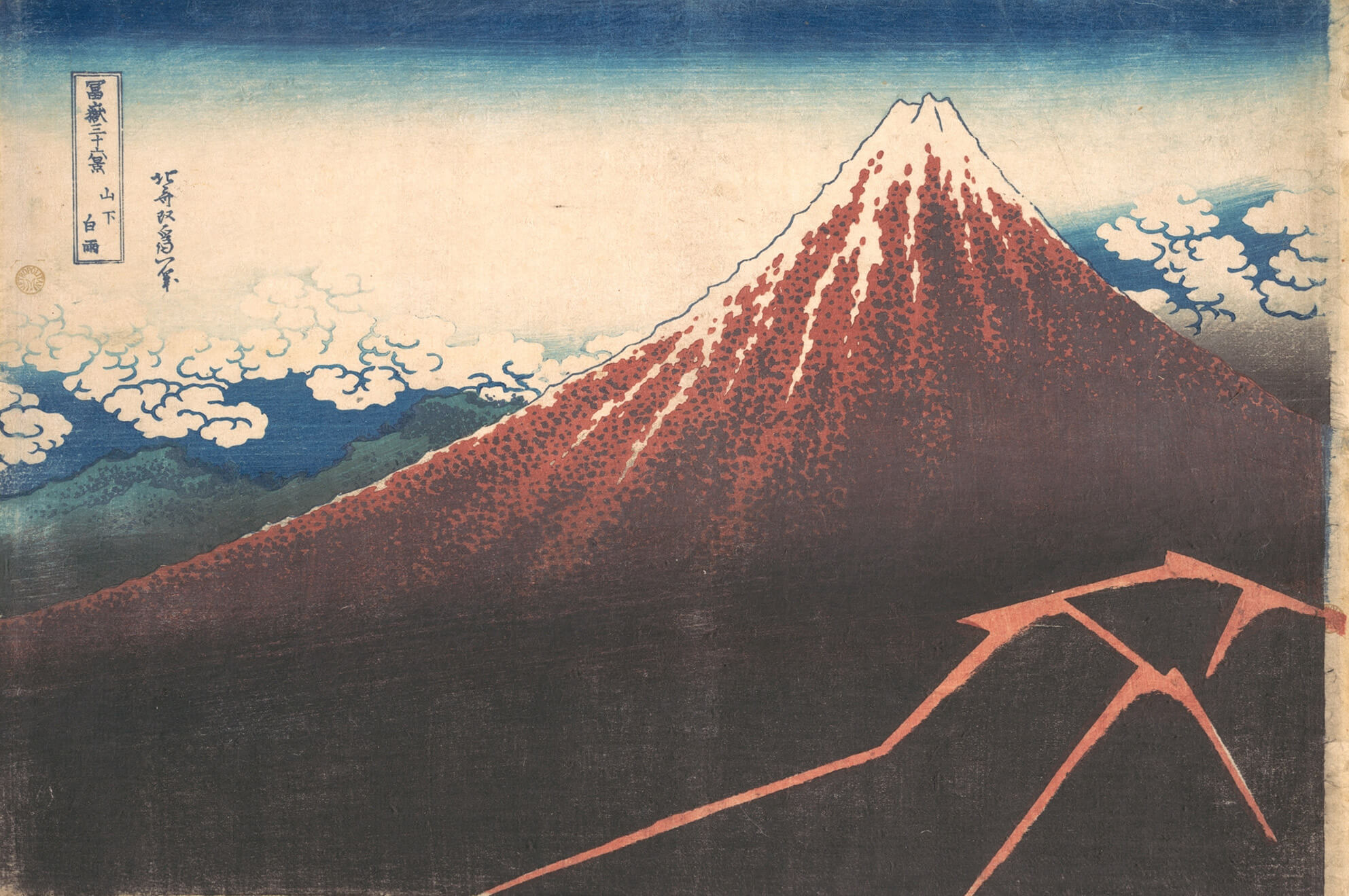

Rather than a picturesque landscape, Time and Eternity is one of the rare “think pieces” in Pemberton’s oeuvre, a conceptual shift from the pictorial to an idea. It is very different from Mosquito Island, 1907, in which Pemberton emphasized the pleasantness of the scene and presented Mount Baker in all its glory. Here, the dead Garry oak is the principal subject and occupies most of the canvas. The twisting limbs and the play of light and shade on its weathered surfaces attract our attention. In 1909 a London reviewer specifically bemoaned this composition: “If the non-essential detail in the foreground had been eliminated, she would have achieved something comparable with the Japanese masterpieces, in which Fujiyama, the eternal symbol of other worldly beauty, silently rebukes the ephemeral.”

Pemberton painted the canvas in early 1908 at a particularly low time in her life and her marriage to Canon Arthur Beanlands—she would soon undergo serious medical surgery and be hospitalized for almost two months. Perhaps the composition was affected by her intention to leave the rectory in Victoria and return to England. The painting is unusual not only in the assemblage of items it portrays but also in the flat dimensionality and redacted detail of its style. Among Pemberton’s known paintings, Time and Eternity is one of the few that adopts a Post-Impressionist approach to express her mood and her personal feelings. She rejected her previous conservative values in order to entertain modernist ideas and experiment with form.

A London reviewer recognized this expansion in a review of her 1909 exhibition at the Doré Gallery in London: “Mrs Beanland’s work carries with it something more than the mere attempt to portray landscape and climate… there is a feeling of mystery difficult to explain.” Harold Mortimer-Lamb (1872–1970), a friend who was also an astute art connoisseur, writer, photographer, and arts patron, purchased the painting when he visited Pemberton in England in 1910, and it remained in his collection until his death.

The Dead Pine, n.d., by Tom Thomson (1877–1917), presents a similar composition—a skeletal husk of a once flourishing tree in the centre foreground, interrupting the viewer’s eye from the scenic rhythm of the lake, shoreline, and distant hills. Surrounding this shattered hulk and flashing vivid scarlet leaves, smaller seedlings suggest renewal. Reviewers suggest that, for Thomson, the tree may have represented life’s struggles or his preoccupation with the Great War, in which some of his close friends were fighting. Clearly, this painting is a “think piece” not unlike Pemberton’s Time and Eternity.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements