Sophia (Sophie) Pemberton (1869–1959), born in Victoria, B.C., determined to be a professional artist—a career not easily accomplished by women at the time. She studied in respected art schools in London and Paris, exhibited widely, received commissions, and sold well. She made a noteworthy contribution to Canadian art, first with fine realist portraits and figure studies and later with landscapes that hint at Impressionism and modernism. Following her marriage, she continued her practice, becoming an associate of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts in 1906. By 1918 a series of debilitating illnesses and family tragedies overwhelmed her, curtailing her art production. During her last three decades, with failing eyesight, she turned to domestic decorative art. Although she lived in England for half her life, she always kept in close contact with her family in Canada.

A Privileged Family Life

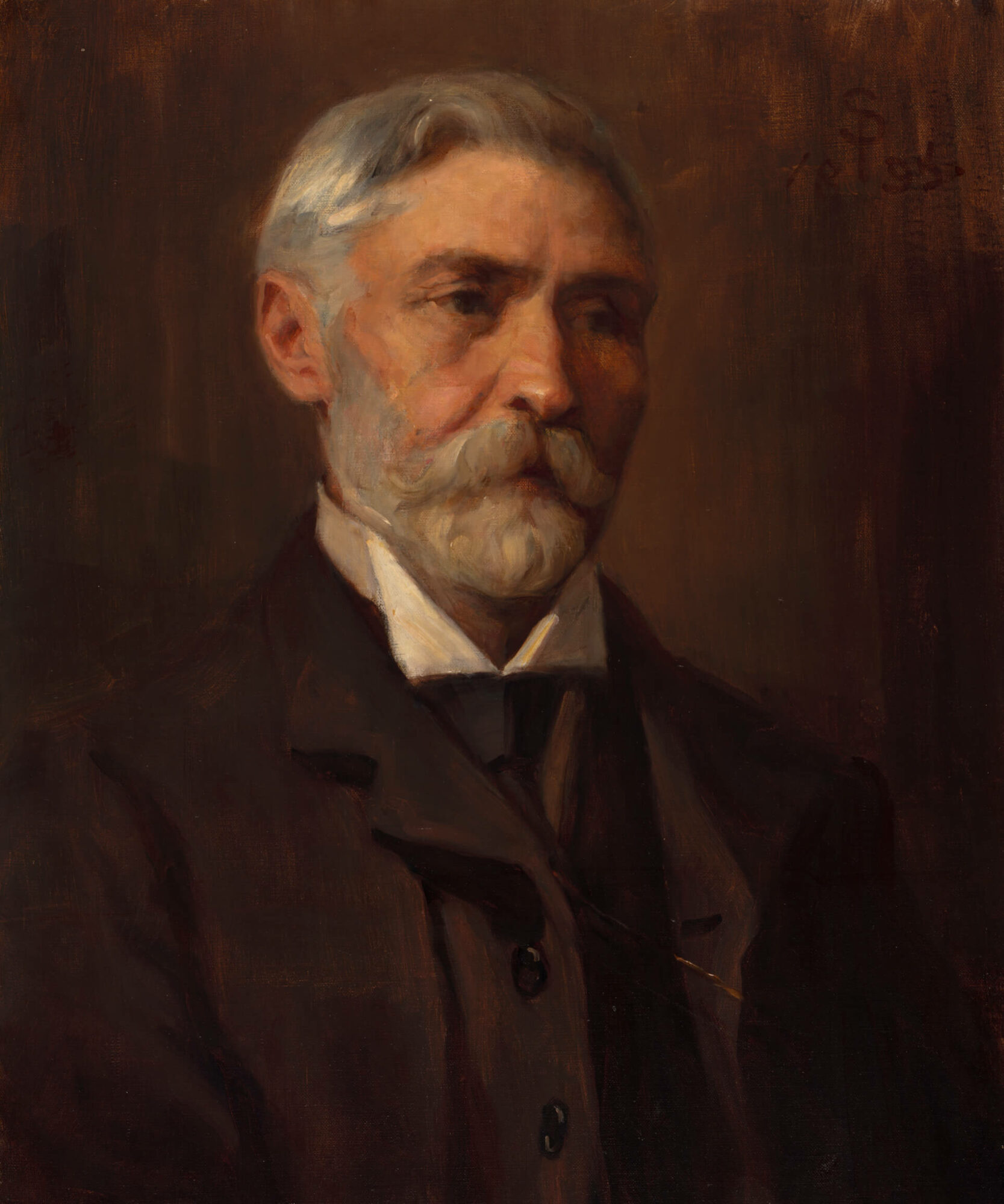

Sophia (Sophie) Theresa, the second child of Irishman Joseph Despard Pemberton (1821–1893) and his English wife, Theresa Jane Despard Grautoff (1842–1916), was born on February 15, 1869, in Victoria, Vancouver Island. Her father had come to the colony as a surveyor for the Hudson’s Bay Company and, after British Columbia became a province in 1871, he entered politics, served as a justice of the peace, and developed successful investments in corporations and real estate. Sophie and her siblings—Ada, Fred, Susie, Joe, and Will—grew up in a closely knit family at Gonzales, a large acreage in the Oak Bay area.

The Pembertons frequently travelled to England for business and to visit family. The children appreciated their extended family, loved travel, and adapted well to new circumstances—all attributes that benefited Pemberton later in life and gave her confidence.

Early on, Sophie seems to have had rudimentary art lessons. A certificate from the Reformed Episcopal School pasted into her scrapbook (her Glory Book) documents an “honourable mention” in painting. Her first-known landscapes date from 1882. Two detailed watercolours, Fire in the Forest and View from Gonzales, made her, at thirteen, the youngest contributor to “A Souvenir of Victoria” album of watercolours, sketches, and photographs presented to Princess Louise when the viceregal couple visited that year. She sketched other scenes in watercolour or pencil while visiting in the Cowichan Bay and Shawnigan Lake areas just north of Victoria or in the Fraser Valley on the mainland. Working en plein air was an acceptable pastime for amateur artists, and several friends, including her neighbour Josephine Crease (1864–1947) and Theresa Wylde (1870–1949), also sketched outdoors, as did Emily Carr (1871–1945).

When Pemberton was fifteen, she and Ada began boarding at a small academy for girls in Brighton, England, and stayed for nearly three years, leaving at term’s end in April 1887. While they were there, they must have had art classes: Sophie was photographed sitting at an easel and an aunt referred to her work in a letter: “I am sorry Sophie has not commenced oil painting… as it takes some time & experience to do much.” Soon after, the siblings returned to Victoria.

Art Training in London

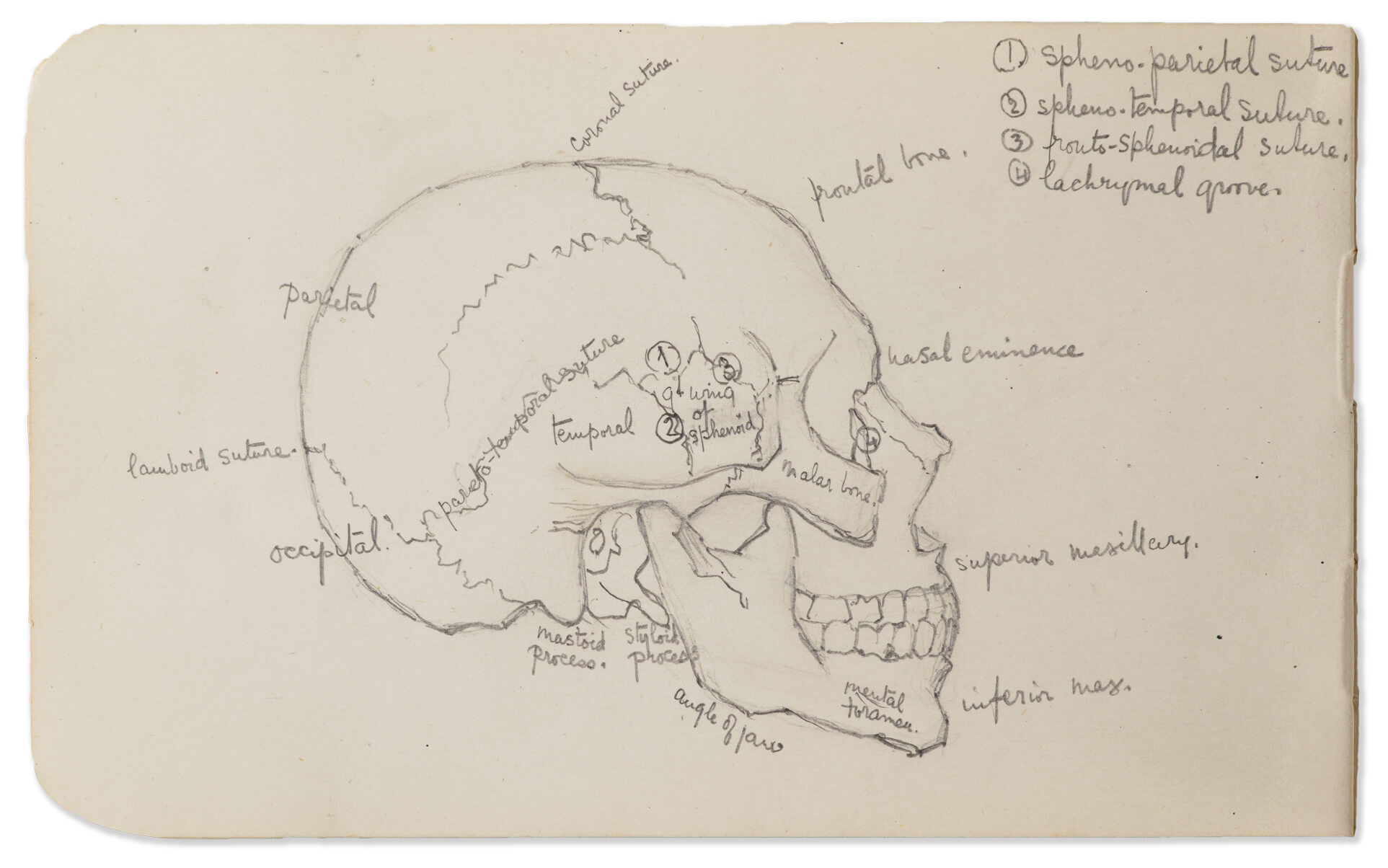

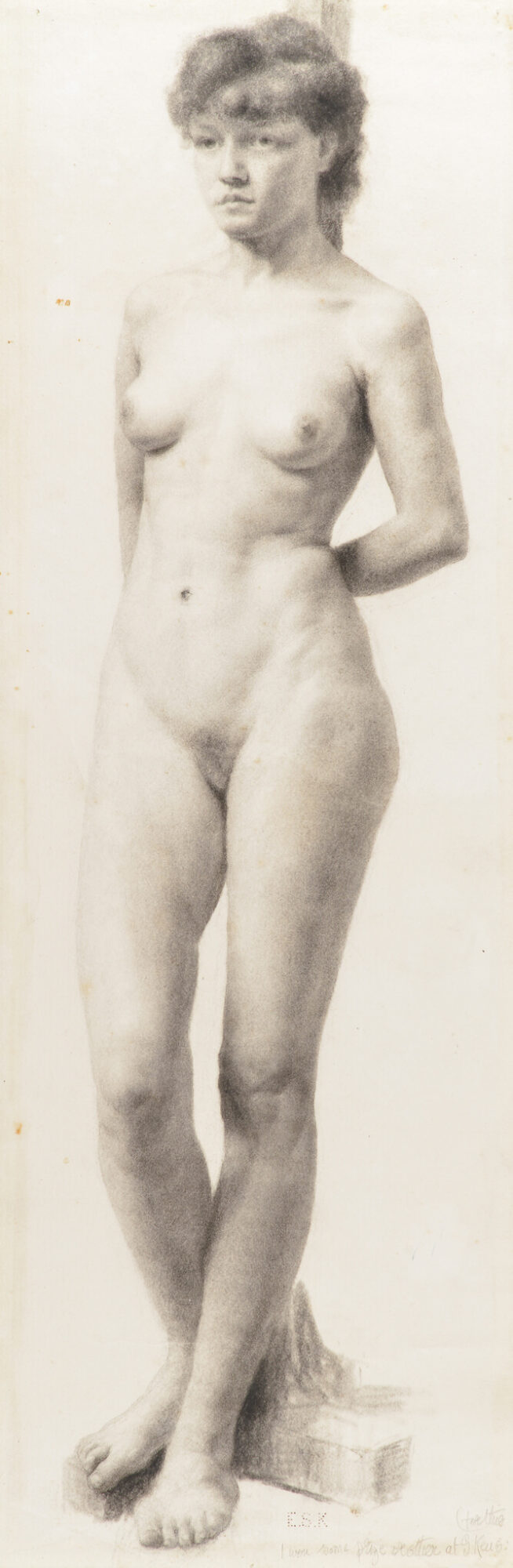

In early 1889 Pemberton, her sister Susie, and their mother returned to England, where Pemberton registered for her first formal art training. Many London academies specialized in classes for “ladies who wish to have the moderate talent which they possess trained so as to be a source of interest and amusement to them,” but Pemberton did not want to be classified as “a dabbler.” Instead, she chose a serious school run by portrait artist Arthur Cope (1857–1940) in South Kensington. She studied there for just over a year, following the traditional academic art program of anatomy classes and drawing plaster casts from ancient sculptures and then live models in pencil or charcoal.

When Pemberton returned to Victoria in October 1890, she continued to paint in her studio at Gonzales, sometimes with Josephine Crease, who would soon leave for art school in England. Her earliest extant British Columbia oil landscape, Cowichan Valley, 1891, is a pleasing but unsophisticated rural scene. For Pemberton, Victoria represented only an interlude in her studies, but she was dependent on her parents’ permission and financial support.

In late April 1892 Pemberton returned to London with her parents. She convinced them to allow her to remain in London and register at the Clapham School of Art for September. She agreed to live with relatives who resided nearby and receive an allowance from a businessman who knew her father. As he explained: “The object of her pressing to remain in London when Wife & I returned was as I understood to work at art to become if possible an ARA [associate of the Royal Academy]… she ought to lose no time & omit no effort at the Studio to accomplish so desirable a result.” Though laudable to have this support, it was unrealistic for women to try to gain this status. Despite increasing numbers of women exhibiting at the Royal Academy of Arts, none were elected as associates until 1922.

Pemberton studied at the Clapham School for about eight months, again following the academic program but also taking a woodworking class. A series of clever informal drawings in her sketchbook depict her teachers and some of the models and fellow students. She worked hard to produce a mass of sketches and canvases and regularly sent works home. Her parents, though proud of her output, entreated her not to overwork even as they remained supportive. “The packet of 8 glorious paintings arrived all OK yesterday. Every care will be taken of them.”

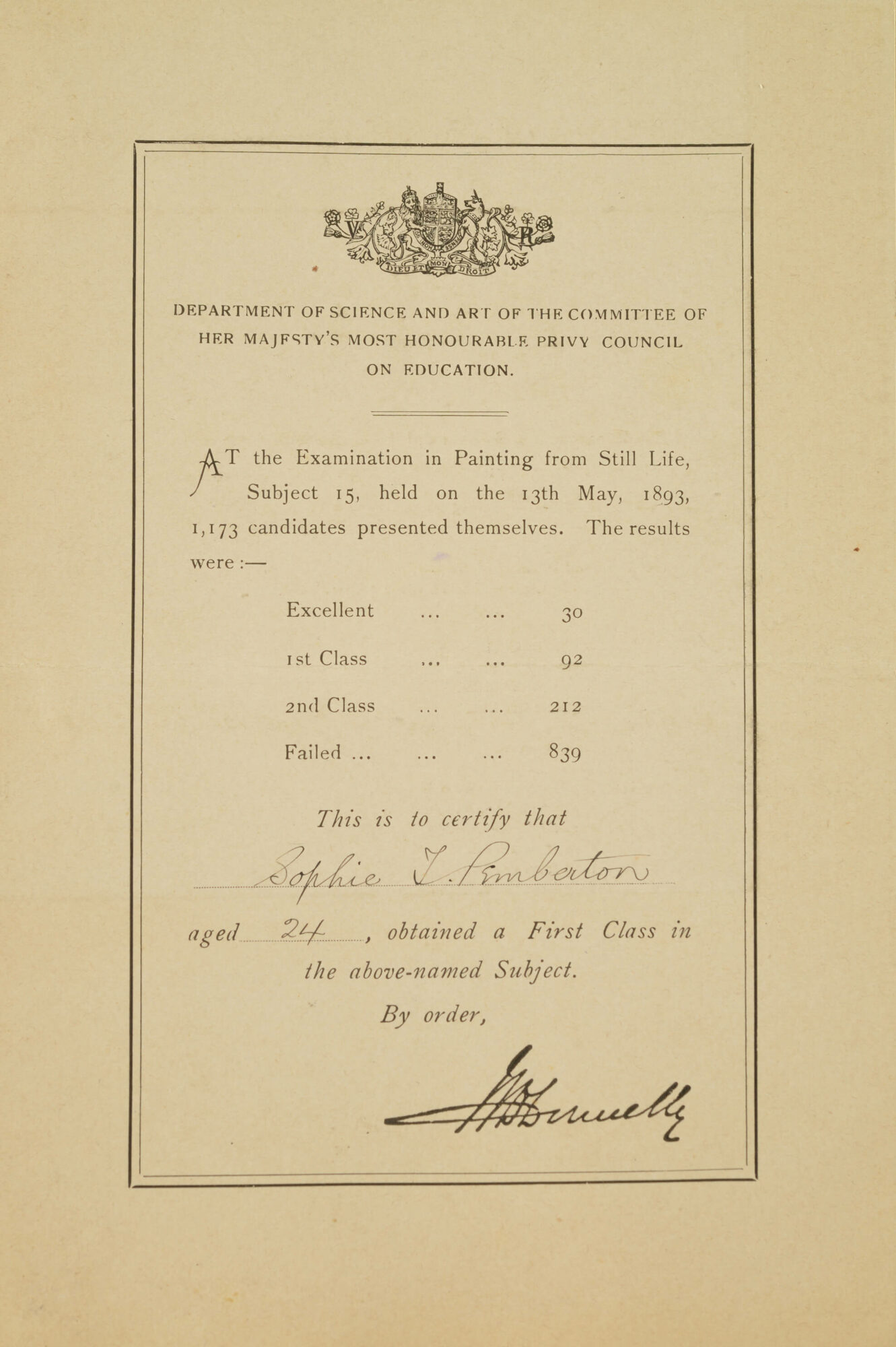

In May 1893 Pemberton sat for the government-regulated exams set by the South Kensington Schools of Art, which oversaw a syllabus delivered in institutions across the United Kingdom. In two of the three categories she entered, she was one of over a thousand applicants. When the results were announced, she was awarded first-class designations in each of “Drawing from the Antique (May 10), Drawing from the Life Subject (May 11), and Painting from Still Life (May 13),” ranking her in the top 10 percent in each one.

With excellent examination results to introduce her, Pemberton and her father discussed options for switching schools, but he left the decision to her: “Decide on the Studio which will be best for your advancement,” he wrote. “Let the difference in price be no consideration, it is not much & sometimes, a higher rate is a decided advantage as regards the class of students who will be your companions for months together.”

In the end, Pemberton selected the Westminster School of Art, beginning in September 1893 and living at the nearby Alexandra House. “Secure the best rooms to be had independent of cost,” her father advised. Her instructor, the portrait and genre painter William Mouat Loudan (1868–1925), was considered to be a favourable teacher. One particularly fine charcoal portrait, Life drawing of a male, 1893, survives from this time.

All might have proceeded positively in such a stimulating environment, but on November 11, 1893, Joseph Pemberton died instantly of a heart attack. Pemberton was heartbroken and, within a few weeks, developed strange physical symptoms including partial “paralysis” in the lower limbs and general weakness. Perhaps it was the first of many episodes of psychosomatic illness she would experience throughout her life when under stress.

There is little detail regarding her art studies during this difficult time, but in March 1894 her mother and sisters arrived and, at term’s end, they all went to Italy for six weeks, returning to London via Paris. “We stayed a week [in Paris] as Ada wanted to see a little of the place & it was hard to tear Sophie away from the paintings,” her mother wrote. Pemberton’s physical and emotional state was still precarious, and she agreed to return home with her family.

Becoming Professional

Pemberton returned to Victoria in time for Christmas. She seemed to rally and resumed her art practice, painting two major series of botanical drawings in watercolour that she presented as gifts to her siblings Fred and Ada. In early January Josephine Crease “saw Sophie and had a chat in the studio,” and a few weeks later Pemberton invited friends and neighbours to see the paintings she had shipped home. This networking reminded Victoria residents of the talented artist in their midst and resulted in at least four commissions to paint portraits.

In London, Pemberton had met the English artist Fanny Grace Plimsoll (1841–1918), who lived part time in Montreal and exhibited there. It may have been this connection that prompted her to submit, from Victoria, two oil portraits from her overseas oeuvre to the Art Association of Montreal (AAM) show in March 1895—in all probability her first major exhibition. At the time, the AAM held considerable prestige and was a significant venue for Canadian artists. Sweet Seventeen and A Normandy Peasant (dates unknown) were available for sale at $25 each.

These initiatives indicate that Pemberton was back on track in her commitment to her chosen profession. She considered herself a practising artist and began to make arrangements for her return to London. Fortunately, her father had been prescient in his estate planning and had provided that his three daughters, on reaching the age of twenty-one, should each receive $1,000 per annum to “advance” them in “art, literature or music, or for the purpose of foreign travel.” This clause gave Pemberton the financial freedom to pursue her dreams and to be geographically distant from social expectations back home.

Emily Carr, in contrast, after three years at art school in San Francisco, was in Victoria teaching children and saving for her own London lessons. Her 1895 ink sketches of scenes around Victoria indicate she probably participated in some of the group jaunts organized by Josephine Crease, but there is no record of Carr socializing with Pemberton at this time. A few years later, in England, Carr wrote that she “had not seen Sophie yet.”

In August 1895 Pemberton travelled with a friend by rail across Canada and then to New York, where she boarded the Umbria bound for Liverpool. The connections she had from her London art schools proved to be durable and strategic and, by November, she had moved into “artistic cloisters.” Over the next eight years, while living in the stimulating artistic environment of Chelsea and Kensington, she visited renowned galleries and exhibitions, established a social network of English, Irish, Swedish, and Canadian artists, and enjoyed one of the most productive phases of her career.

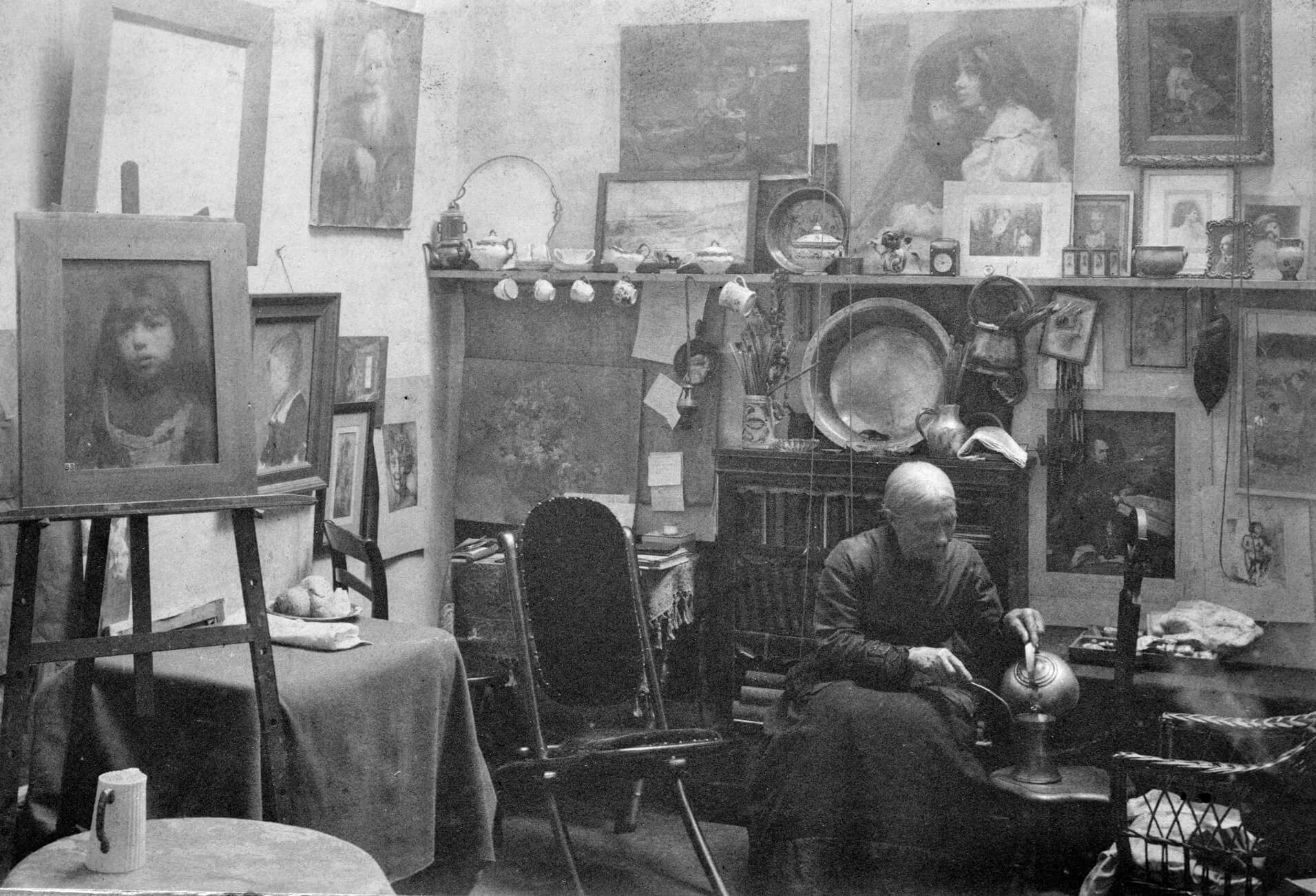

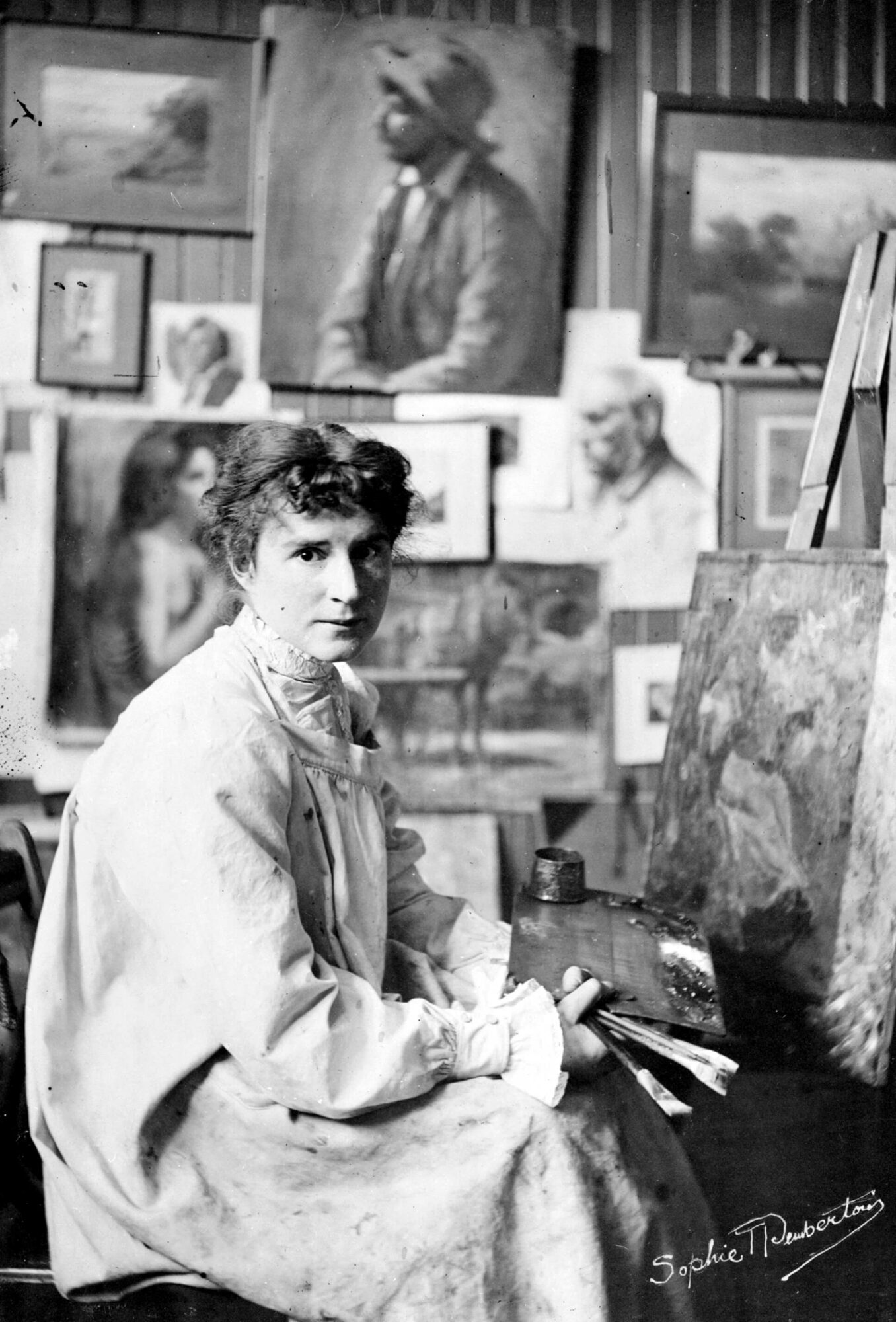

Pemberton moved into #3 Stanley Studios, Park Walk, Chelsea. By having a studio, she presented herself as a serious artist, and she listed this address in London directories and in exhibitions until 1903. Independent living and the culture of the studio world soon became a liberating tonic for her as her colleagues influenced her career as well as her social views. In 1897, for example, women rented six of the eight studios in the building, and they all exhibited at the Royal Academy of Arts. The Swedish expatriate Anna Nordgren (1847–1916), who lived in Studio #4, had founded London’s feminist 91 Art Club as a space where women artists could meet and exhibit. In 1896 she and Pemberton travelled to Normandy and Brittany to paint and, the following year, attended women’s suffrage meetings in London. Two Canadians from Ontario also lived close by: Sydney Strickland Tully (1860–1911) in Studio #7, and Florence Carlyle (1864–1923), fresh from Paris, in Chelsea. Tully and Pemberton sometimes shared models, such as the older woman seen in a photograph of Pemberton’s studio. Pemberton’s known 1896 London exhibitions include the 91 Art Club at Clifford’s Gallery and the Artists’ Guild at the Albert Hall.

Pemberton also showed her paintings in Liverpool, Brighton, and Birmingham. She celebrated her first big break when the Royal Academy of Arts accepted Daffodils, 1897, a large oil painted exquisitely in the academic realism style, for its annual London summer exhibition. While travelling with family to Italy that autumn and winter, Pemberton let her studio to the Irish artist Constance Gore-Booth (1868–1927), who had previously worked at the Slade School of Fine Art and was a staunch ally of Nordgren in feminist causes. When Pemberton was in Ireland in the summer of 1897, she visited Gore-Booth at her family estate, Lissadell. It seems that she painted Little Boy Blue, 1897, while in Ireland.

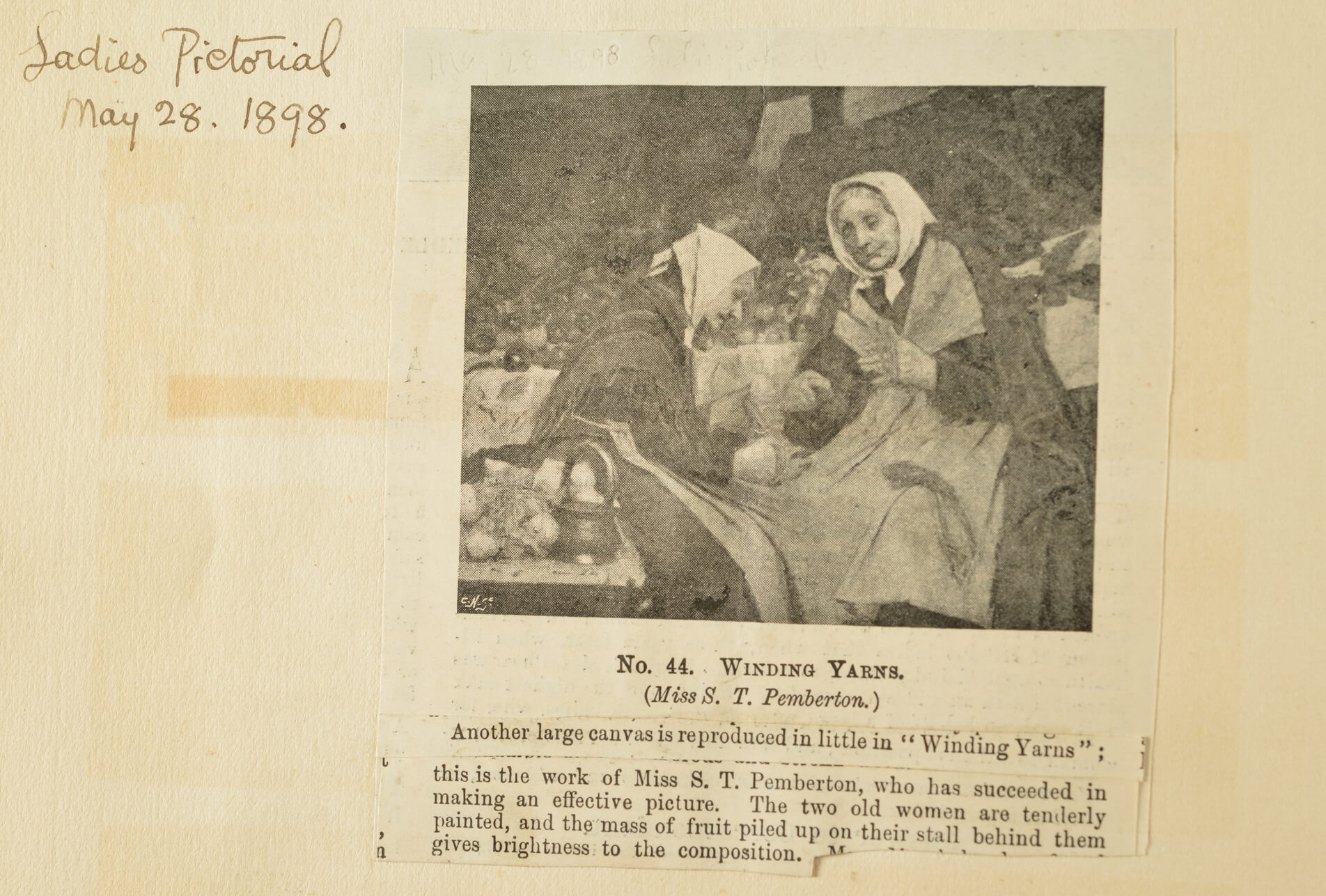

In 1898 Pemberton repeated her winning combination: strong showings at exhibitions in London and other major English cities as well as her second acceptance by the Royal Academy of Arts. The Lady’s Pictorial reported: “Miss Sophie Pemberton shows French influence in ‘Little Boy Blue’ in which the colour is nicely felt; the modelling of the head is good, and the flesh tones are soft and pure.”

Paris and the Prix Julian

In late summer 1898 Pemberton applied to the Académie Julian, established by Rodolphe Julian (1839–1907) and one of the city’s most renowned private art schools. It had a solid reputation as an academy where women, though in separate studios, could compete equally with men for recognition. The training there in academic realism might also have been infused with modern influences including Impressionism. Instructors were freed from formulaic teachings, and many, rather than advocating one style over another, allowed the students to follow their own inclinations.

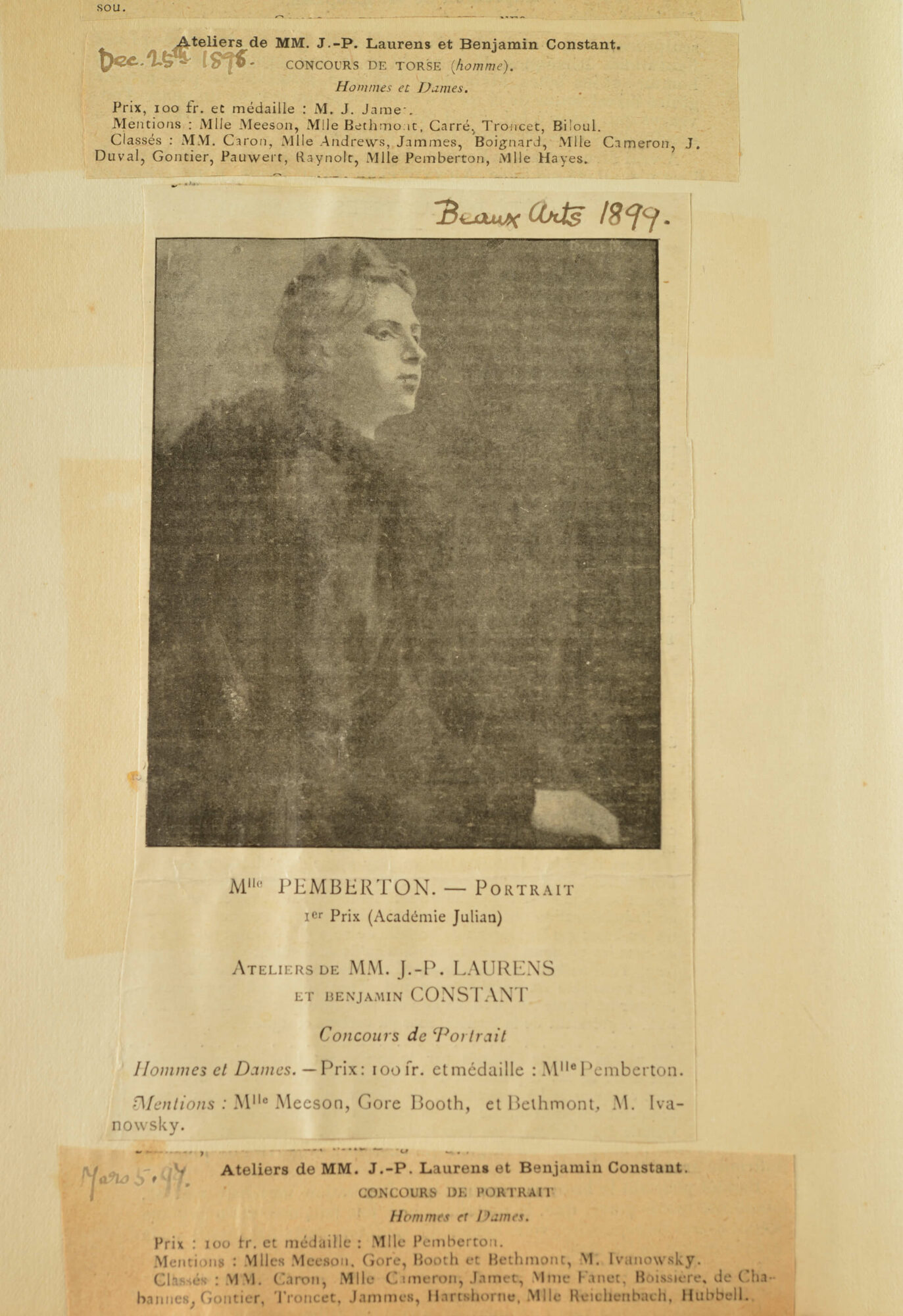

Pemberton arranged accommodation in a furnished apartment on the Left Bank and registered at the women’s studios at 5, rue de Berri—one of the ateliers where the well-known academicians J.P. Laurens (1838–1921) and Benjamin Constant (1845–1902) taught. Pemberton studied at Académie Julian for almost two years and, in 1899, she briefly took an evening class with the American artist James McNeill Whistler (1834–1903). By November 1898 her figure studies began to be recognized in monthly concours among the students in the atelier and within the wider school.

Three months later, Pemberton shot to prominence when she won the Prix Julian, the medal (along with 100 francs) awarded for the best portrait by a student from the ateliers of Laurens and Constant. Reported in the magazine Beaux Arts, it was a significant honour in its time—especially for a woman, because this category was open to both men and women. Julian himself explained, “All the students compete together, and the examining professors are not told either the name or the sex of the competitors till the results are declared. It is astonishing… how often women have the best of it in these trials. Especially is this true of portraiture, which is generally supposed to be more or less a man’s specialty.” In 1900, when Pemberton again competed against about one hundred other students, “the Julian Smith Foundation Prize of Chicago, worth three hundred francs, [was] awarded on equal footing to Miss Pemberton and to Mr. Edgar Muller.”

During these two years, Pemberton again exhibited widely, though she was disappointed when a major canvas, Winding Yarns, 1898, was not accepted for the Royal Academy of Arts. It did the rounds of provincial exhibitions to great success, however, and seems to have sold. Her portrait Bibi la Purée, 1900, debuted in Paris, and she submitted two works to the Women’s International Exhibition in London. A large oil, Tarring Ropes, 1899/1900, a genre scene of two Cornish fishermen, appeared in the Canadian section of the Exposition Universelle in Paris. During class breaks, she travelled to her London studio, where she stored her canvases and performed the arduous task of preparing them for transport to exhibitions in England and Canada.

In late May 1900, after an absence of five successful years, Pemberton returned to Victoria.

Canadian Sojourn and European Travels

Originally Pemberton intended to stay in Victoria over the summer months, but she soon found herself drawn into the social scene in her hometown. Her mother assumed that society and family took priority over art, and invitations to teas, dinners, and boating parties absorbed her time. Despite the tension, she carved out sufficient time to prepare a major canvas for exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts in 1901. The large oil Interested, 1900, depicts two young Victoria women reading together. Later, retitled as Un Livre Ouvert, she dispatched it to France for the 1903 Paris Salon.

As the months passed, her old unexplained malady—ongoing weakness in her legs—returned and she spent the first few months of 1901 in a California medical sanatorium. She resumed her artistic production soon after her return, sketching models, completing oils and watercolours en plein air, conducting classes for local amateurs, and painting major canvases such as Spring,1902. In early January 1902 she advertised her professional status by exhibiting her new works at Waitt’s Hall. The British Colonist commented:

She intends returning to Europe at an early day and has very kindly placed some of her pictures on exhibition…. To be able to see pictures of such merit is an advantage…. [including] her two latest important works, “John-o-Dreams,” and “The Twilight of the Lilies.” These pictures will be submitted to the Royal Academy and the Paris Salon.

In autumn 1902 Pemberton returned to her studio in England and then to France, where she visited her mentor and friend Amélie Beaury-Saurel (1849–1924), the wife of Rodolphe Julian, a strong feminist, and a successful portrait painter. In December, with fellow Canadian and Académie Julian friend Lillie Cameron (1873–1958), she left for five months in Italy, living in Rome and Florence, painting, learning Italian, and absorbing the legacy of Renaissance art. She was also strategizing about her future—whether to stay in Paris for the winter or, as she wrote to her friend Flora Burns in Victoria, to try “in London again & see if I can get portraits to do.” But again, the physical troubles resurfaced, and she was bedridden.

No sooner had Pemberton returned to London than her mother and sisters arrived and whisked her off first to Normandy. She took her bicycle “Susannah,” so she could disappear with her portable easel, stool, and art kit to paint outdoors. She particularly enjoyed recording the topsy-turvy architecture in Caudebec-en-Caux before they left for the winter in Italy.

While there, Pemberton managed complicated arrangements to transport paintings stored in her London studio to several exhibitions, meeting all the deadlines: John O’Dreams, 1901, submitted to the Royal Academy of Arts; Un Livre Ouvert, 1900, to the Paris Salon; and others to Manchester and Newcastle. On her return to London in May, between specialist medical appointments, she networked. As she explained to her friend: “Went by appointment to see Lord Strathcona [Sir Donald Smith, the Canadian high commissioner]; this is a secret as Mother would have wanted to accompany me & say pretty things… he is coming to the studio with his wife & daughter some day.”

Again in 1904 from Italy, she organized for Bibi la Purée, 1900, to go to the Royal Academy of Arts and for Un Livre Ouvert, 1900, to travel to the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts (her debut there). From that exhibition, the academicians chose it to be part of the Canadian contingent to the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis in 1904.

By mid-1904 Pemberton had left #3 in Stanley Studios. Once again she appears to have been at the whim of her family’s schedules, and it became more difficult for her to maintain her earlier ambitions. Little is known about her specific success in selling her art, although, judging by the many exhibited titles listed for sale whose whereabouts remain unknown, she must have enjoyed good sales.

In June 1904, Pemberton capitulated to pressures and returned to Victoria, bringing with her almost all the paintings from her studio. That autumn, thirty of these paintings were exhibited at the Provincial Agricultural Exhibition, followed by a solo show, The Pemberton Pictures, in Vancouver. The canvases and watercolours showed the depth and breadth of her work in England, Italy, and France. She also completed a commissioned portrait of Dolly, the daughter of Harold Mortimer-Lamb (1872–1970), whom she met when he judged the art works at the fair. They kept in touch over the decades, and he photographed her and purchased more of her paintings.

Marriage and a Turn to Landscape

Pemberton soon became reacquainted with Canon Arthur Beanlands of Christ Church Cathedral. A recent widower, Beanlands, twelve years her senior, had presented a series of art lectures at Gonzales in 1895 and seemed to be an enthusiastic supporter of the arts. Pemberton, now thirty-five and removed from her independent life and artistic support network in London and Paris, was again living at home with her mother, who was becoming more difficult to appease. Plagued by recurring physical ailments, she felt considerable social pressure to conform to expectations: “Mother does not seem very wishful to have me home,” she wrote to her friend.” Perhaps marriage with a congenial, well-read, and sympathetic arts lover who would support her art practice was the solution. Beanlands had four children between the ages of seven and seventeen, and the three older girls would soon reach adulthood. Only the youngest, Paul, would benefit from mothering—and this child stole her heart.

On September 11, 1905, Pemberton married Canon Beanlands—and her life and path as an independent artist dramatically shifted. Initially she had her own studio in the rectory, but within months it became a space where Beanlands and the children came and went. She was not deterred, however. She turned her hand briefly to journalism and published two articles on models she had known. Over the next two years she continued to paint and received several portrait commissions, including one for her neighbour Lady Crease, whose daughter Josephine continued to be active in the local arts scene, and for prominent people such as Lieutenant Governor Henri Joly de Lotbinière. She successfully applied to be an associate of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts, where she exhibited in 1907, but she sent no paintings abroad.

As she tailored her work to the opportunities available, Pemberton moved away from portraiture to focus on landscape, as she had in 1903 in Brittany. Trips up-island with friends offered opportunities to paint outdoors, and she appreciated the variety of scenery available around Victoria. Her time in England had exposed her to more recent art styles, so she was a few years ahead of Emily Carr, who would not understand this “fresh seeing” until she too studied in France from 1910 to 1911. Meanwhile, she and Carr supported the newly formed British Columbia Society of Fine Arts in Vancouver and Victoria’s Royal Jubilee Hospital, for which they each designed “charming posters… which will afterwards be framed and used to adorn the play room in the children’s ward.”

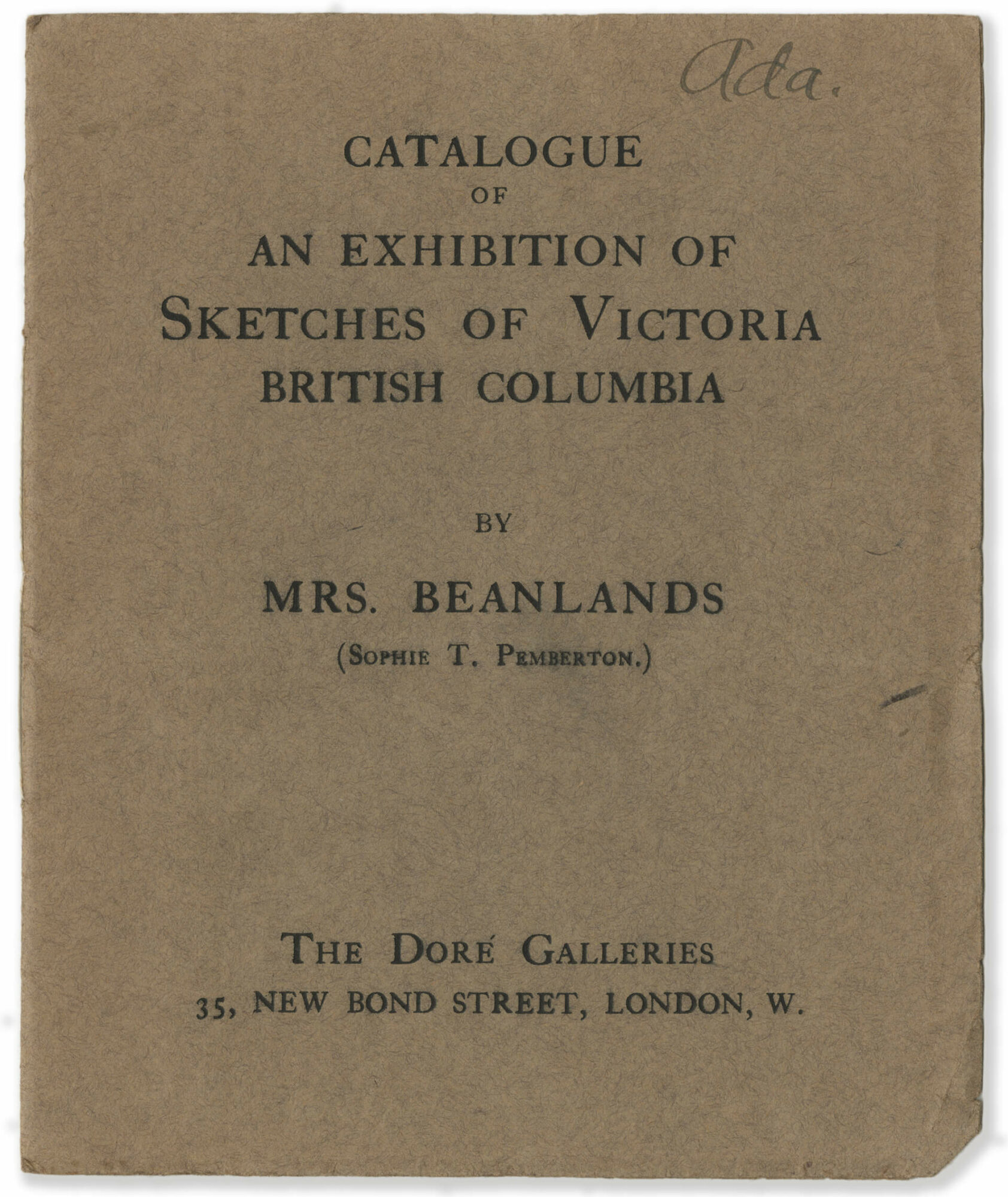

Pemberton decided to present in a solo exhibition of British Columbia paintings at the respected Doré Gallery in London—and booked the space for May and June 1909. In preparation, she painted Mosquito Island, 1907, over a few days while visiting friends; Macauley Plains, 1907/08, overlooking the Strait of Juan de Fuca; and other works. She experimented also with form, creating Time and Eternity, 1908, which focused more on personal expression than on the landscape.

It is remarkable that, despite two lengthy hospitalizations in early 1908, she kept on track. In August 1908 the Beanlands held two “at home” afternoons where she displayed thirty-eight recently completed landscapes—a “charming collection of pictures,” in the words of the Daily Colonist. There she announced her move to London, ostensibly for preparation for the exhibition. In fact, she packed for a much longer stay and dismantled her studio. It would be eight months before Beanlands joined her.

Return to Europe and Family Tragedy

In May 1909 Pemberton mounted Sketches of Victoria, British Columbia at the Doré Gallery on New Bond Street. Without revealing specifics, a reviewer reported it was “under very distinguished patronage.” Studio International noted: “As a landscape artist she… has developed her own style as a student of nature upon the Pacific Coast, a region of brilliant sunshine and pellucid atmosphere.” “She is an artist of great merit,” wrote the Daily Express. With these positive reviews, Pemberton’s exhibition seemed a success, and again, given that the location of most of the works she displayed is now unknown, they must have sold. Unfortunately, just at that time she was derailed by a family tragedy.

The eldest Beanlands daughter, who was living in Ontario, was badly burned in March and died in June. Beanlands had joined Pemberton in time for the exhibition but was caught on the wrong side of the Atlantic. Grieving, he resigned his post at Christ Church Cathedral and decided to remain in England.

On August 6 Pemberton arrived in Montreal, where she spent a day with Harold Mortimer-Lamb and Laura Muntz (1860–1930). She was heading to Victoria to pack their belongings in the rectory and to fulfill a promise to paint “the angels for mother’s chapel”—a decorative mural inside the newly built Pemberton Chapel at the Royal Jubilee Hospital. On her way back to England, she left A Chelsea Pensioner, 1903, with Mortimer-Lamb, so he could deliver it for exhibition at both the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts and the Art Association of Montreal.

Once Pemberton returned, the strain in the marriage increased and she spent more time apart from Beanlands, often travelling in Europe. Canadian family members also visited for extended periods. In 1910 she submitted Memories, c.1909, to the Royal Academy of Arts and successfully networked for further portrait commissions. Her accomplishments between 1907 and 1910 speak to her discipline and commitment.

In 1912, borrowing money from her family funds, Pemberton purchased Wickhurst Manor overlooking the village of Sevenoaks, Kent. The home’s centre was a medieval hall and boasted a seventeenth-century fireplace. Previous owners had restored it well and tended its extensive grounds. The Beanlands moved there in February, and she displayed her canvases on the extensive walls. They participated in local cultural events and, together, became active in the women’s suffrage movement. By November Pemberton was a representative for the local branch of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies, and later, in March 1914, on the national council of the Suffrage Service League. But she still kept up with her art. Canvases from these years include a landscape titled Weald Church, Kent, 1915, and interiors such as The Amber Window at Knole, 1915, which was hung at the exhibition of the Royal Academy in 1916.

At that point, further tragedy engulfed the family. Two of her brother Fred’s sons, who had often visited Wickhurst Manor, were killed in service during the First World War. In August 1916 Pemberton’s other brother Joe died while hiking, followed days later by her mother. The following February the dog-cart Pemberton was driving collided with a lorry, and her head injuries resulted in a long convalescence. Then, in September 1917, Beanlands unexpectedly died. Plagued by debilitating headaches over the next three years, Pemberton struggled as nurses came and went and every remedy proved unproductive. She could no longer read or paint, and, crushingly, in May 1919 her beloved stepson, Paul, was killed in a plane crash.

The friendship of her neighbour Victoria Sackville-West (mother of poet, novelist, and garden designer Vita Sackville-West, who, as Virginia Woolf’s friend, was connected to the Bloomsbury Group) proved to be a lifeline, as did a neurological consultation that “cured” her headaches. Lady Sackville-West encouraged Pemberton to use her artist’s skills on a small scale by decorating domestic pieces—lampshades, tea trays, glassware—both for herself at Knole House and to sell through her shop, Spealls, in London. Pemberton enjoyed great success with these pieces.

Late Career and Final Years in Victoria

In January 1920 Pemberton, at the age of fifty, married Horace Deane-Drummond, a widower fifteen years her senior who had few pretentions about art. With tea estates in Asia, he was well travelled and, in Pemberton’s words, “a great gentleman and a keen sportsman.” They embarked on a world tour, spending time with his adult children who ran his properties in India and Ceylon and where he hunted big game. Asia was a new experience for Pemberton and, for the first time in years, she sketched—a Hindu temple in Madurai in southern India. “The temple is too wonderful,” she wrote. “‘Yalis’ are these mythological beasts & I have painted the mandapam with them & the shrines & screaming parrots.” This realist-style painting is the only known work from her trip. Eventually they arrived in Victoria for an extended stay to meet the family. When Pemberton designed a décor for a new haute couture shop, her “Persian” theme attracted much attention.

In another fortuitous move, Pemberton discussed Emily Carr (whom she had just visited) with Mortimer-Lamb when she saw him in Vancouver in 1921. He then called on Carr, was “greatly impressed” with her art, and told Eric Brown (1877–1939) of the National Gallery of Canada about her, leading to her “discovery.”

The couple continued their travels, and Pemberton occasionally painted landscapes such as La Napoule Bay, 1926, and accepted portrait commissions. In 1930 she was again widowed. After the sale of Wickhurst Manor a few years earlier, they had moved to the Deane-Drummond estate, Boyce Court, in Gloucester. She decided against living there and returned to London, where she took a flat on Priory Walk, close to her old Stanley Studio. She wrote frequently to family and friends in British Columbia, interested in the news from home. During the Second World War, she refused to decamp and survived the Blitz, despite a hit on her house. Failing eyesight limited her to close-up work, but the demand for her painted trays and other small pieces kept her busy.

In 1949, aware of her own and her sisters’ fragile health, Pemberton returned to Victoria, accompanied by her major canvases and favourite furniture. She rented a flat in a genteel Oak Bay building, near the beaches she had explored as a child. Her local reputation was immediately rekindled when the Arts Centre—a small, temporary downtown facility—displayed some of her larger canvases in a successful exhibition that underscored “the crying need for more adequate premises.” A permanent facility opened in 1951, known today as the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria.

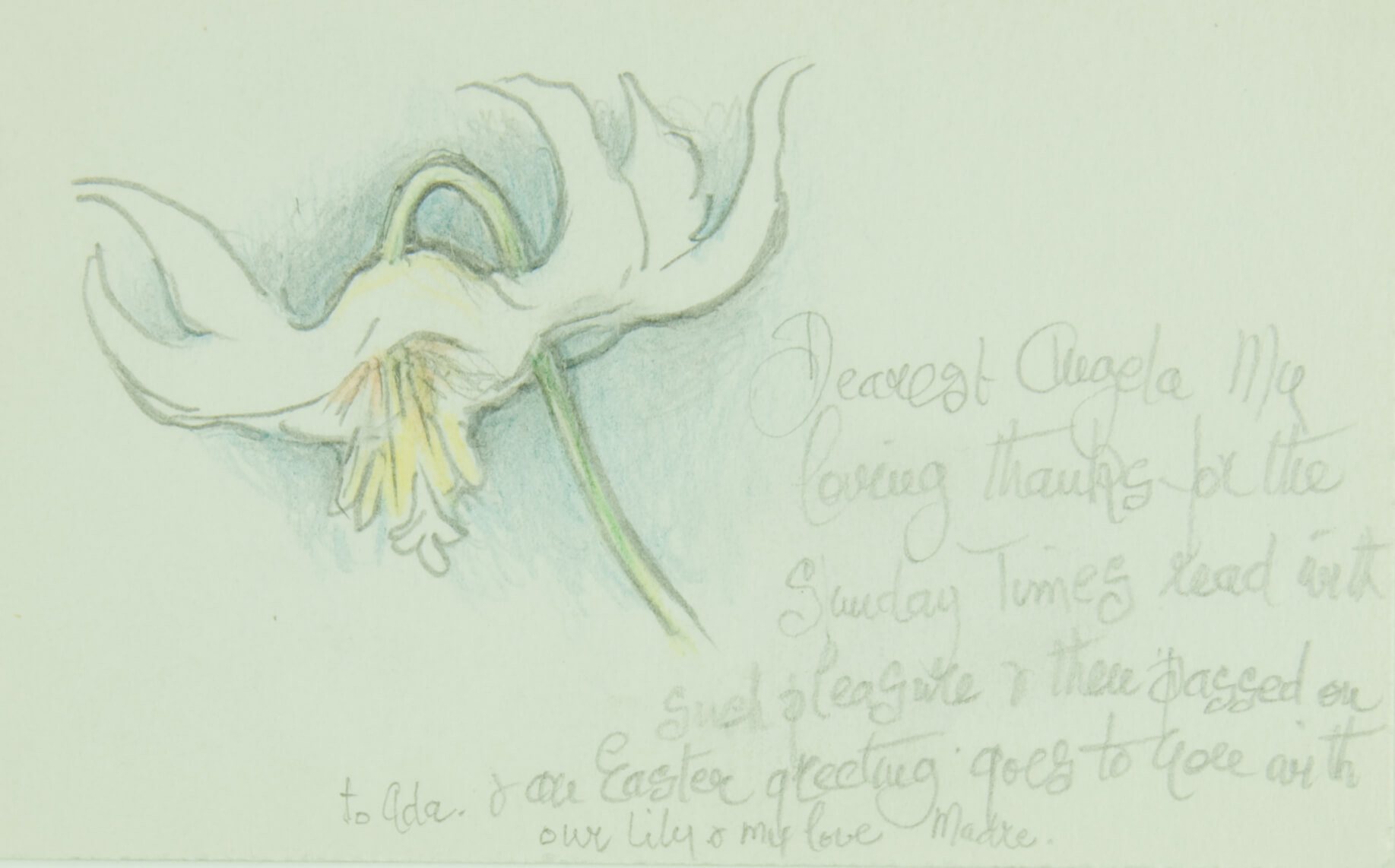

Pemberton continued to paint small domestic pieces. She was content to go beachcombing for seashells to sketch, along with the flowers in her sister Ada’s extensive garden. Many of these small coloured-pencil sketches adorn her letters from these years.

In late 1959, after a short illness, Pemberton died. She is buried alongside her parents, with the epigraph “Blessed are the pure in heart” inscribed on the family monument.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements