Robert Houle’s artistic practice embraces cultural traditions associated with his Saulteaux heritage, reflected in his use of colour, his formalism, and his sensitivity to materials and their symbolic properties. As well, the Abstract Expressionist school, and especially the painter Barnett Newman, has been a major influence on his work. Houle’s practice combines abstract and figurative techniques, and features multiple stylistic approaches. He employs collage, text, sound, video, and mixed-media installation, although painting remains his most essential form of expression.

Abstraction and Colour

Some Indigenous cultural traditions avoid representation in their designs because it impedes creating the “essence” of an object. By integrating elements of Anishnabe heritage with abstraction, fusing Saulteaux and modernist spiritualism, Houle reconciles contemporary art trends with such Indigenous traditions. From the beginning of his artistic journey, Houle was attracted to and nourished by modern art movements and practitioners—such as Neo-Plasticism, Abstract Expressionism, and the Plasticiens—and geometric Anishnabe designs and traditional quillwork. His influences in abstraction include several iconic figures: Piet Mondrian (1872–1944), Barnett Newman (1905–1970), Jackson Pollock (1912–1956), and Mark Rothko (1903–1970), artists whose works depended upon structural clarity and the expression of spirituality and emotions through colour fields.

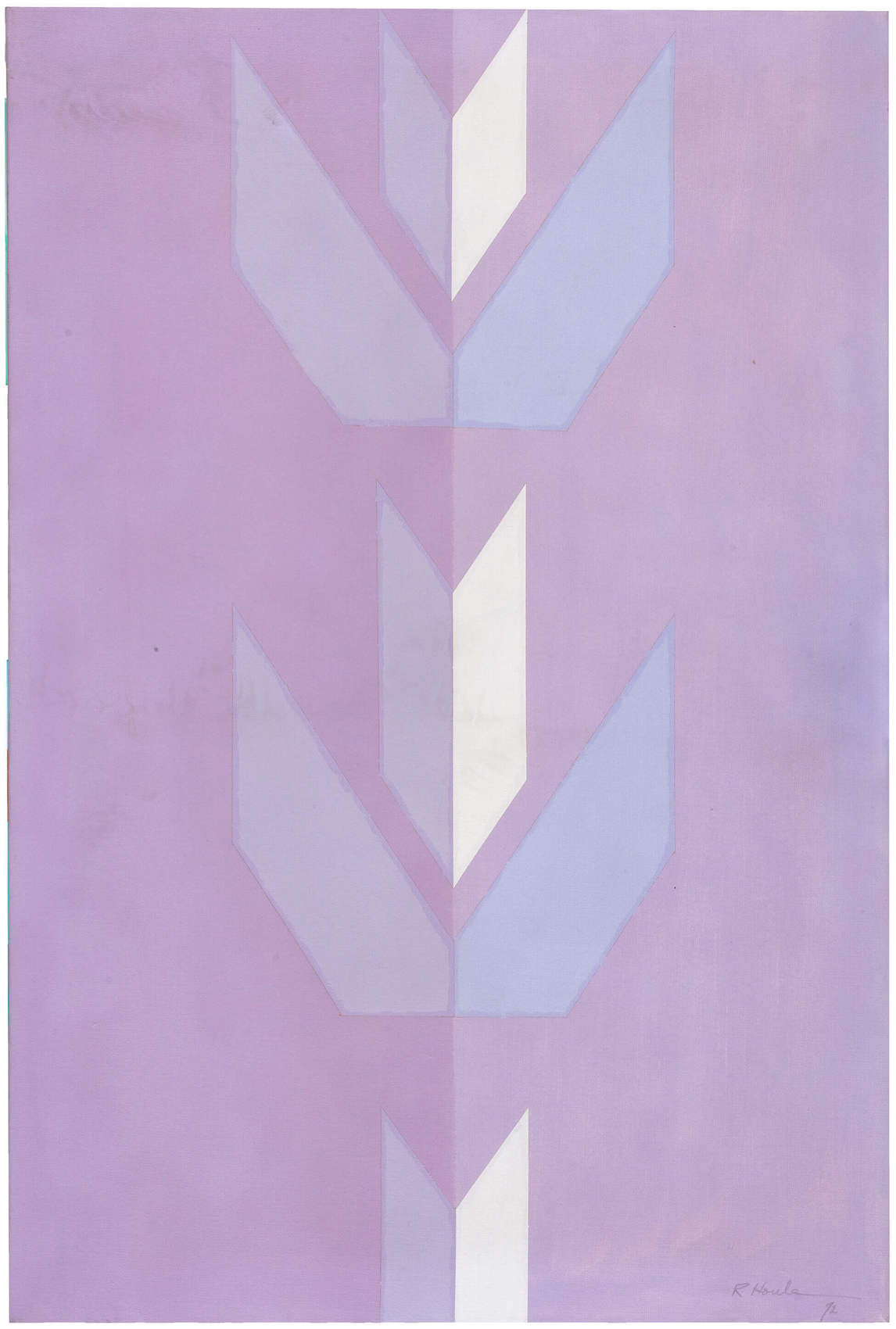

One example of his blending of modern art and Indigenous designs is Houle’s painting Ojibwa Motif, Purple Leaves, Series No. 2, 1972. The work’s leaf-like abstractions resemble traditional Anishnabe geometric designs yet echo a stylistic approach used by New York abstractionist Frank Stella (b. 1936) in its monochromatic geometric forms and shapes. Houle attributes his use of abstraction in early works such as Red Is Beautiful, 1970, to his time at McGill University as a serious student of abstract art, and to his research on sacred objects, such as warrior staffs, parfleches, and Sun Dance poles found in the permanent collection of the National Museum of Man in Hull (now the Canadian Museum of History).

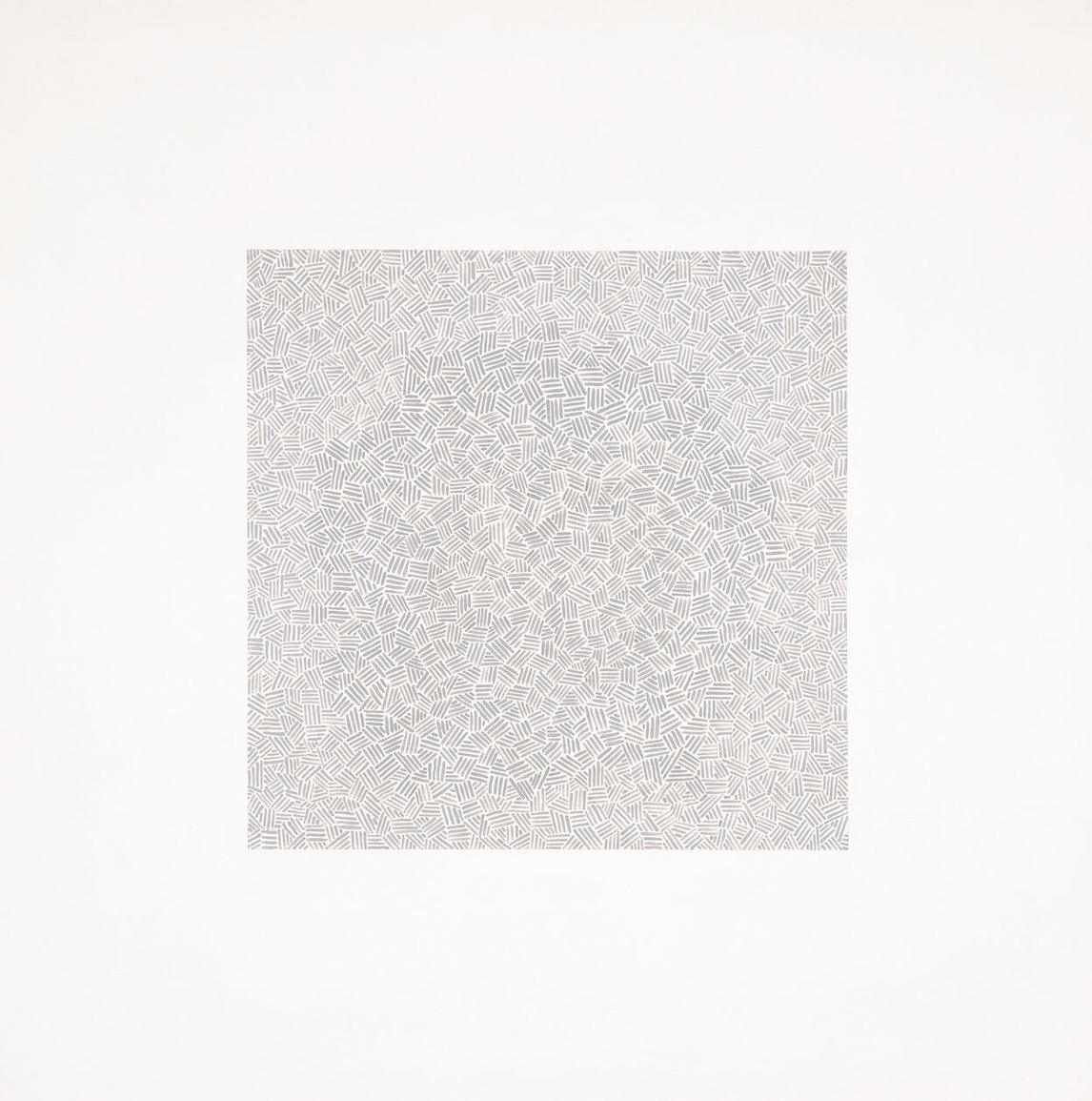

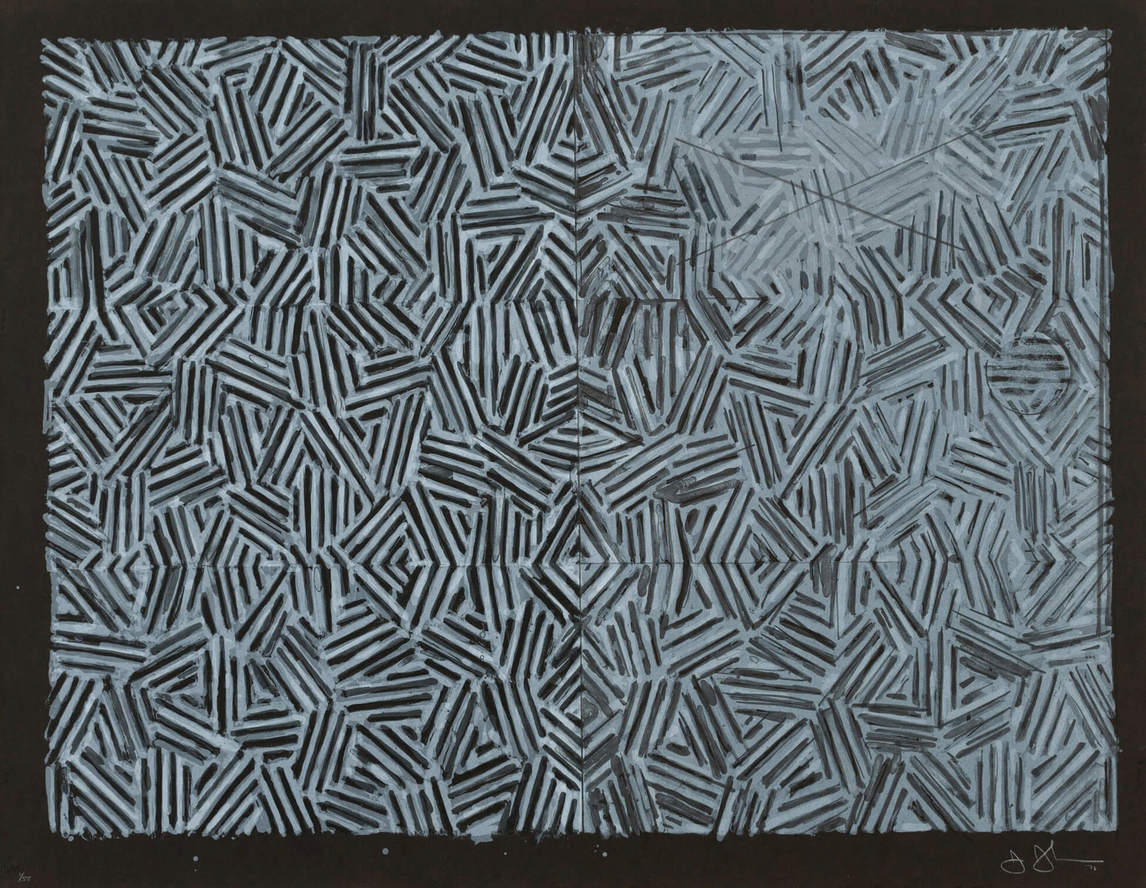

For Houle colour and light is spiritual, and the commingling of Native spiritualism and modernism through colour becomes a dialogue between the spiritual and poetic. In an untitled abstract series from 1972 inspired by love poems, Houle uses the tradition of sacred geometry and symbolic colour to speak of the earth and the cosmos. The paintings are composed of simple geometric shapes and muted colours, as in Wigwam and The Stuff of Which Dreams Are Made. Their spare quality embraces spiritual abstraction as practised by Newman, Rothko, and other Abstract Expressionists and in turn, with reference to traditional Ojibwa geometric designs, asserts the survival of Native spirituality within the modern world. In paintings such as Square No. 3, 1978, and Punk Schtick, 1982, Houle uses small taches to create an effect of linear hatching that echoes both quillwork embroidery and the style of Jasper Johns (b. 1930), whose work Houle discovered in the late 1970s.

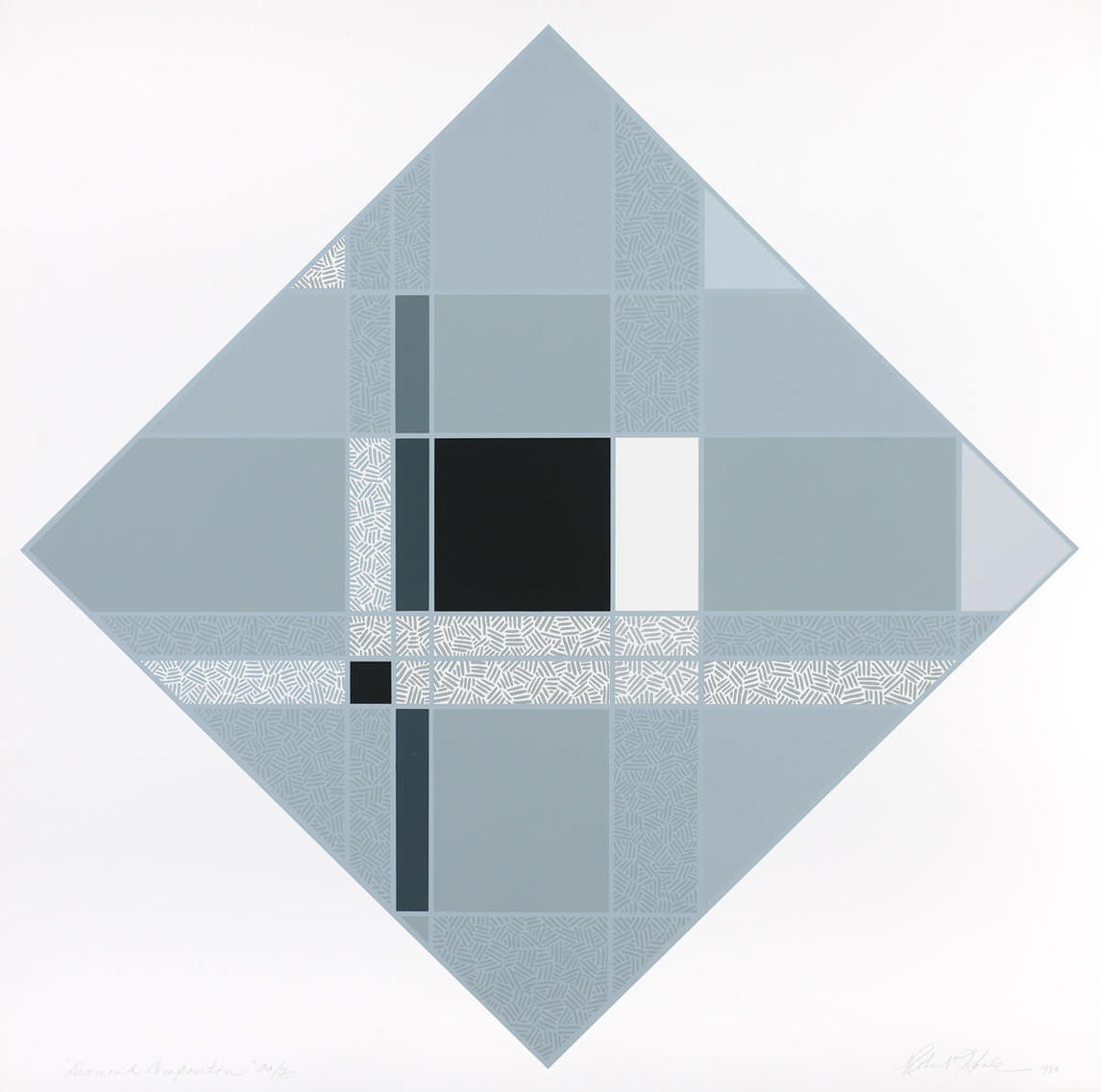

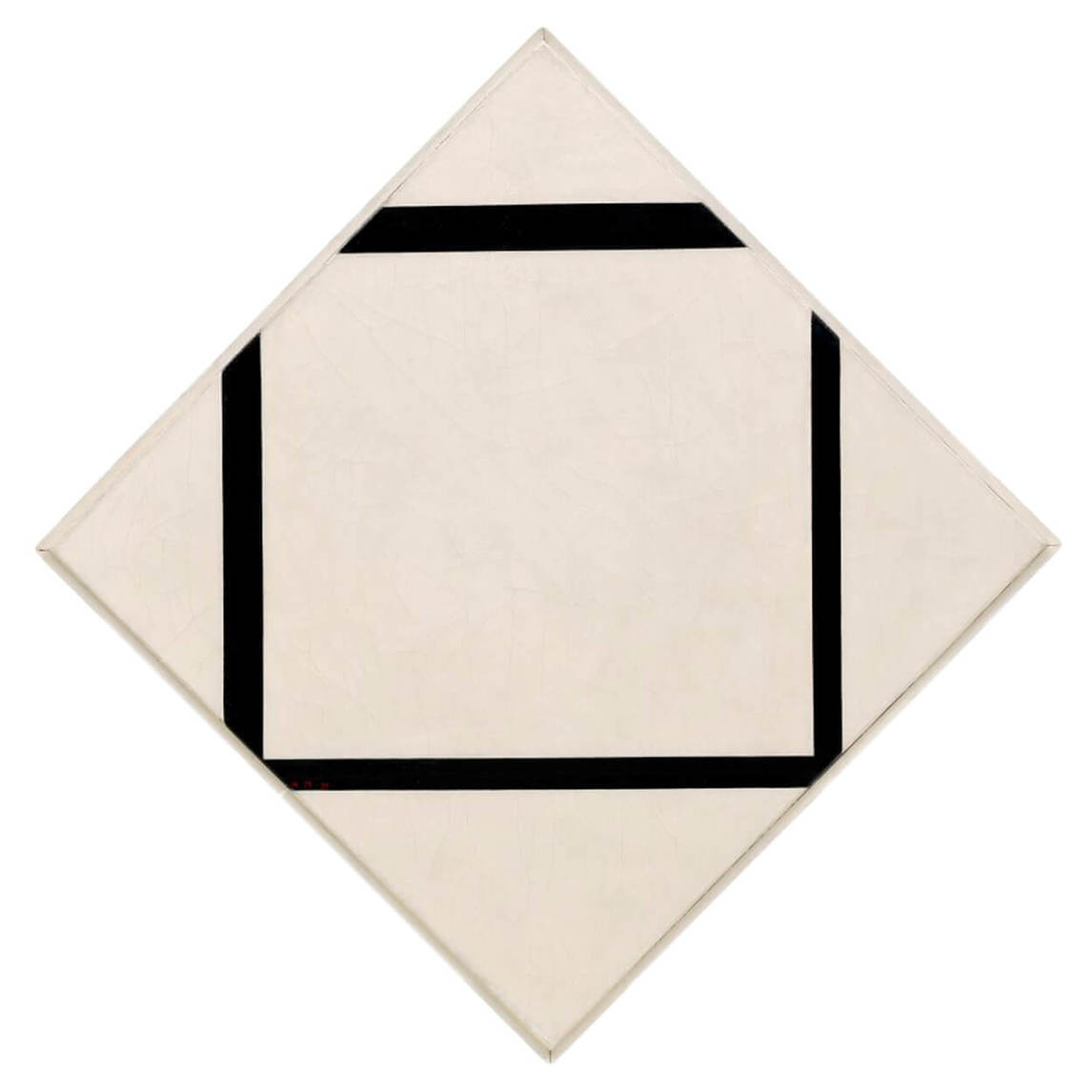

Houle often overlays Indigenous motifs on practices associated with Western art. For example, Diamond Composition, 1980, recalls Mondrian’s diamond-shaped geometric works. Using a monochromatic blue, Houle’s spiritual colour (given through ceremony, as part of Anishnabe tradition), Houle disrupts the painting’s geometry by incorporating cross-hatching—parallel strokes that resemble porcupine quills. By doing so, art historian Mark Cheetham says, Houle “infects” the purity often associated with modernism. The cross-hatching creates an intrusion or aesthetic tension in the work because it “adds an additional element”—a technique that Houle borrowed from the Suprematist theory of Kazimir Malevich (1878–1935). Throughout his oeuvre, Houle’s “additional elements” range from porcupine quills to the symbol of a Saulteaux Morningstar to the overlay of archival photographs on text.

Houle also often conceives landscape in abstract terms. Muhnedobe uhyahyuk (Where the gods are present), 1989, for example, shows large fields of expressive and symbolic colour while it testifies to the grandeur of the light, water, and sky of Manitoba. Houle writes, “There is no word for ‘landscape’ in any of the languages of the ancient ones.… In Ojibwa, whenever the word uhke is pronounced, it is more an exaltation of humanness [being connected as part of nature] than a declaration of property.” The canvases are brushed loosely and their distinctiveness is enhanced through gestural marks, crosses, and vertical, horizontal, and oblique lines that reference warrior staffs and quillwork. Reminiscent of Rothko’s spiritualized colour fields, the softly edged rectangles of unmodulated colour each have an upper and lower register that can be read as sky and earth. The interior spaces are articulated by blended, rather than hard-edged, linear elements. Across the canvas is Houle’s characteristic gestural mark, which resembles a spontaneous signature. This gesture permeates all of his paintings and for him is the “the healing line in his art.”

Influence of Barnett Newman

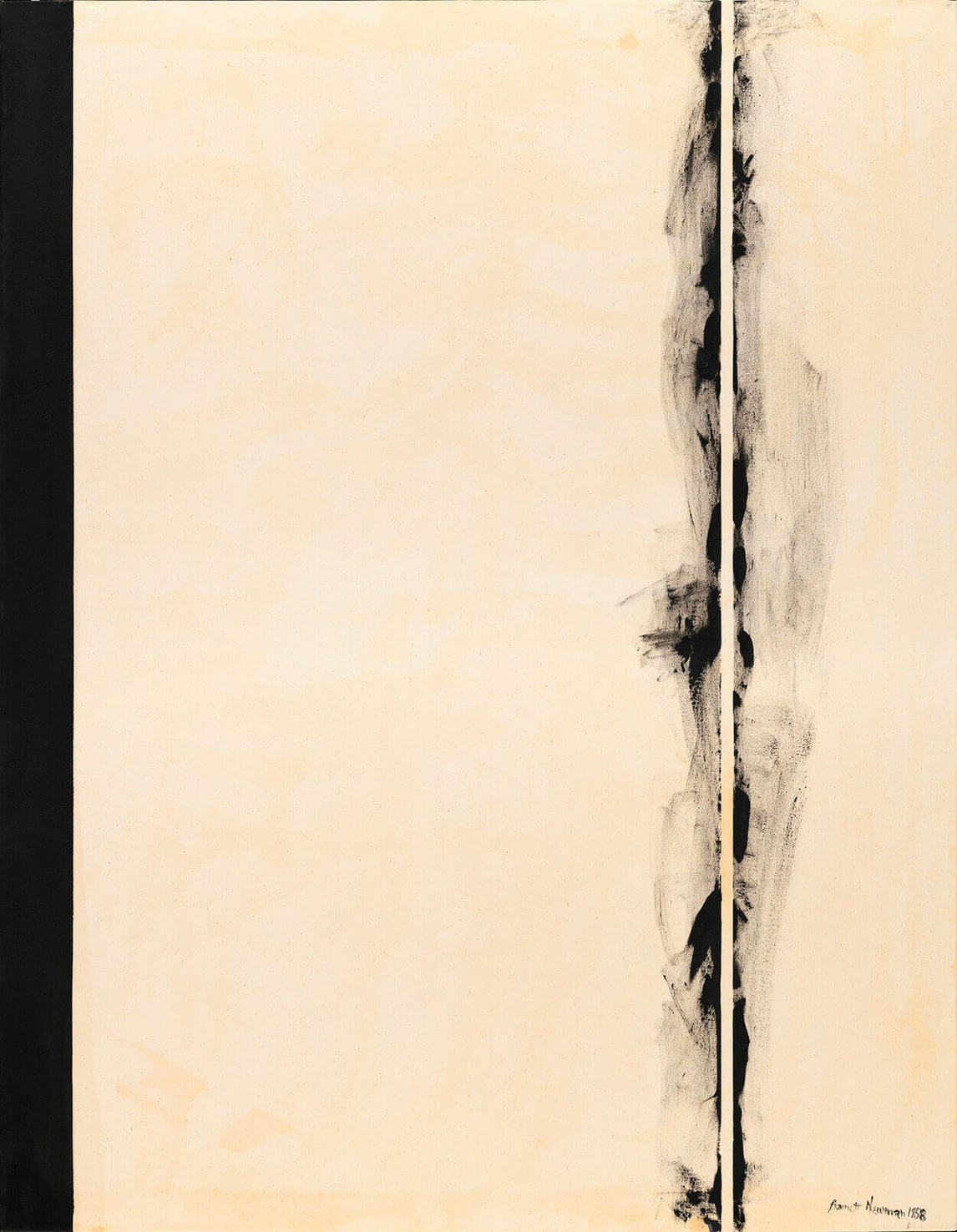

The Abstract Expressionist painter Barnett Newman is perhaps the singular stylistic and technical influence on Houle’s artwork. Houle recalled, “I was standing in the gallery at the Stedelijk Museum looking at Piet Mondrian’s work and turned around and there it was, Barnett Newman’s Cathedra and beside it Cantos. It encapsulated all I aspired for.” The lack of any reference to nature literally or indirectly through symbols or colour in Mondrian’s work was disappointing for Houle, who comes from what he calls “an earth-centered culture”; Newman’s artwork propelled Houle’s practice in a new direction. Newman, Houle stated, “saved me from Mondrian.”

Like Houle, Newman felt keenly the spiritual power of ancient and historic Native American art, although he never studied it. Newman organized exhibitions, as in Northwest Coast Indian Painting (with Tony Smith), held at the Betty Parsons Gallery in New York City in 1946. For his own artwork, Newman searched for a spiritual power similar to what he encountered in Indigenous art; and he insisted on the aesthetic value of Northwest Coast art rather than its ethnographic merit—a position Houle appreciated, along with the American artist’s understanding of abstraction as form and emotion.

Place looms large in the practice and theory of both artists. Newman produced an immense colour-field abstraction triggered by the expansive space of northern Canada in Tundra, 1950. This work influenced Houle’s abstracted representation of a northern Manitoban landscape in Muhnedobe uhyahyuk, 1989. Both artists also produced abstractions that referenced historic conflicts: Newman in Jericho, 1968–69 (when Jericho was occupied by Israel during the Six-Day War of 1967), and Houle in Kanehsatake X, 2000 (referring to the Oka Crisis of 1990).

Newman and Houle honoured heroic figures—Newman with Ulysses, 1952, an homage to the classical Greek king of Ithaca, and Houle with a series of works celebrating Chief Pontiac, as in Pontiac Conspiracy, 1997. Also significant are the serial abstractions addressing biblical themes: Newman in Stations of the Cross, 1958–66, and Houle in Parfleches for the Last Supper, 1983. That Newman was Jewish taking on Catholic subject matter inspired Houle, as Saulteaux, to do the same.

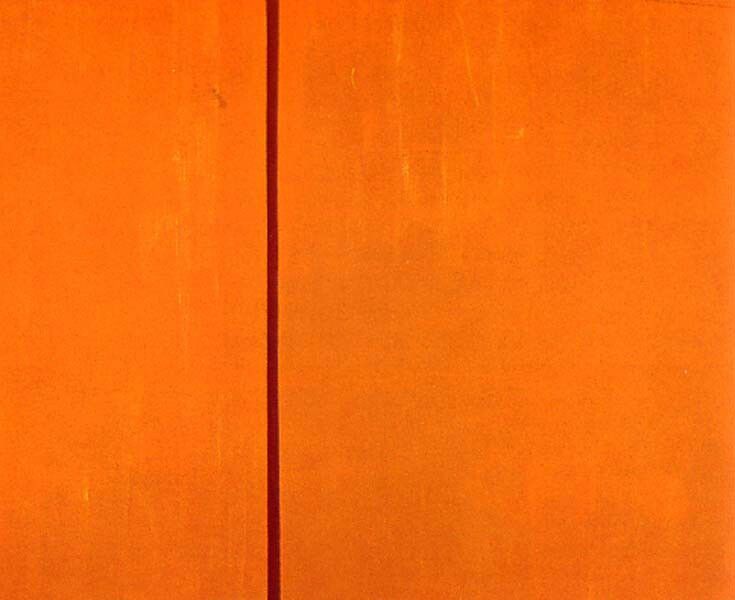

Similar to Newman, Houle paints large fields of expressive colour to evoke emotion. Unlike Newman, Houle’s use of abstraction is informed by a desire to reverse the history of excluding Indigenous artists from museums and public art galleries. Although his iconic painting Kanata, 1992, quotes Newman’s use of red and blue in the work Voice of Fire, 1967, Houle’s appropriation of these colour fields serves a political end as well. The red and blue signify his anguish for the Indigenous position between the two European countries—British and French—that formed the nation state of Canada. As well Houle’s Palisade I, 1999, and Palisade II, 2007, contain direct visual references to Newman’s three-part abstractions—the Onement series, 1948, and Stations of the Cross—with their vertical bands of colour, or “zips.” However, in Houle’s works, the green and white vertical bands represent the formal structure and memorial function of wampum belts.

Appropriation and Deconstruction

One of the most powerful and persuasive ways to address historical inaccuracy or identity politics is appropriation, usually through photographs and text. Revisiting images and writings from the past or popular culture allows artists to call attention to the ideological dimensions of visual representation, raising questions about subjects such as race, ethnicity, gender, and sexuality. The reworking of images can be an affirmative gesture, a method of investing culture with new truths. Since the beginning of his career, Houle has been addressing issues of cultural appropriation and representation in his work. Re-appropriation as a means of reclaiming Indigenous identity and sovereignty is a core strategy in his oeuvre.

Premises for Self-Rule, 1994, was the first work in which Houle incorporated photographs—in this case, old postcards with ethnographic photographic images that document a group of Indigenous men and women gathering at Fort Macleod, Alberta, in 1907. Chosen for their narrative qualities and strategically placed over excerpts of text from treaties stencilled on Plexiglas, the photo emulsions play an important role in activating both the formal and historical content of each work. Parallel to a process of deconstruction (the photographs masking parts of the treaties) is a powerful tension between the written word of the texts and the oral tradition signified by the photographs.

Houle carries appropriation and deconstruction further in his nomenclature work that explores Western cultural appropriation of names for commercial purposes (for example, Washington Redskins, Edmonton Eskimos, Oneida flatware, Jeep Cherokee). Until recently, the use of such epithets was so entrenched that it was not questioned. In the mid-1990s, Houle began creating works that delicately probe the objectification of Indigenous peoples and heroes such as chiefs Geronimo and Pontiac, as in Kekabishcoon Peenish Chipedahbung (I Will Stand in Your Path Till Dawn), 1997. Here Houle appropriated reproductions of thirty-six vintage Pontiac automobile advertisements over which he laid text in vinyl lettering on behalf of eighteen Indigenous nations who joined the original bearer of the Pontiac name—Kaskaskia, Miami, Ojibwa, Winnebago, Mascouten, Fox, Ottawa, Kickapoo, Wea, Huron, Piankashaw, Seneca, Delaware, Mingo, Potawotomi, Shawnee, Menominee, Sauk. Whatever subliminal messages may have been intended by the advertisers, Houle’s alterations subvert them. In framing these mid-century icons and superimposing his own comments, Houle reclaims his history and heritage.

Emulation of the Sacred

Running through Houle’s artmaking is the emulation of ritual objects. Houle envisioned in the practice of painting the potential to restore life to Native materials that had been left for dead inside ethnographic museums and galleries. He began making works resembling parfleches, warrior staffs, and shields with the intent to rehabilitate the sacred objects.

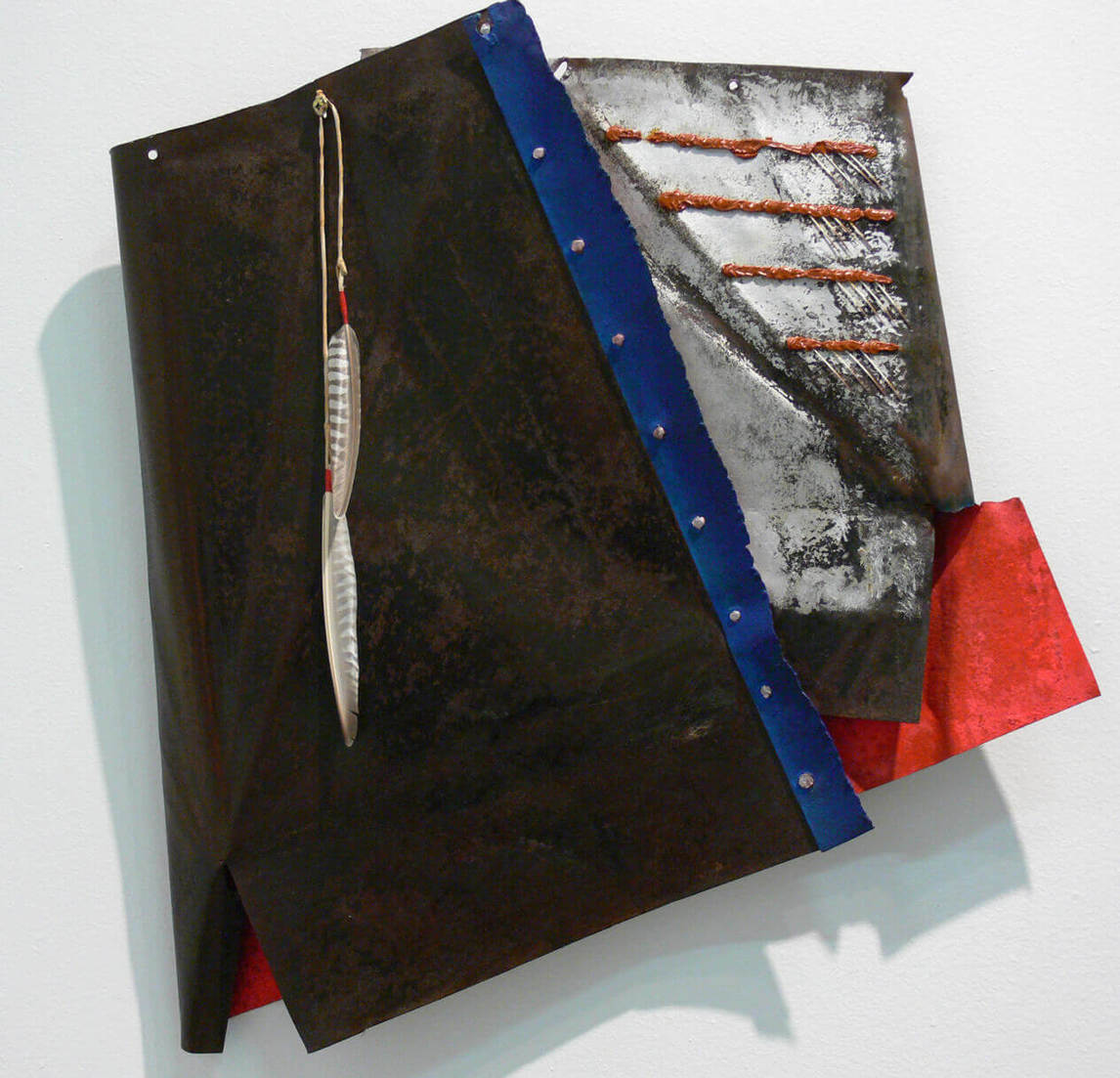

Two early works both titled Warrior Stick, 1982 and 1983, are abstracted renditions of sacred warrior sticks that Houle encountered at the National Museum of Man. In Punk Schtick, 1982 (with a title that belies its serious reference to axis mundi such as poles of the Sun Dance), a cross-hatching technique divides the upper and lower areas; and yet the work connects sky and earth—two highly significant entities in the Plains cosmos and subsequently to Houle’s aesthetic. Another work, Sun Dance Pole, 1982, is similar to Punk Schtick formally but is sculptural in rendition and topped with a tuft of sweetgrass. By merging techniques of abstraction with traditional sacred objects, Houle communicates the nature of these Indigenous symbols of the Plains as elevated beyond the physical and into the realm of the spiritual. These works are precursors to others in which he uses abstraction in rendering images while also employing symbolic colour, as in Parfleches for the Last Supper, 1983; incorporating materials such as the steel used in Innu Parfleche, 1990; and emphasizing shape, as in Drum, 2015.

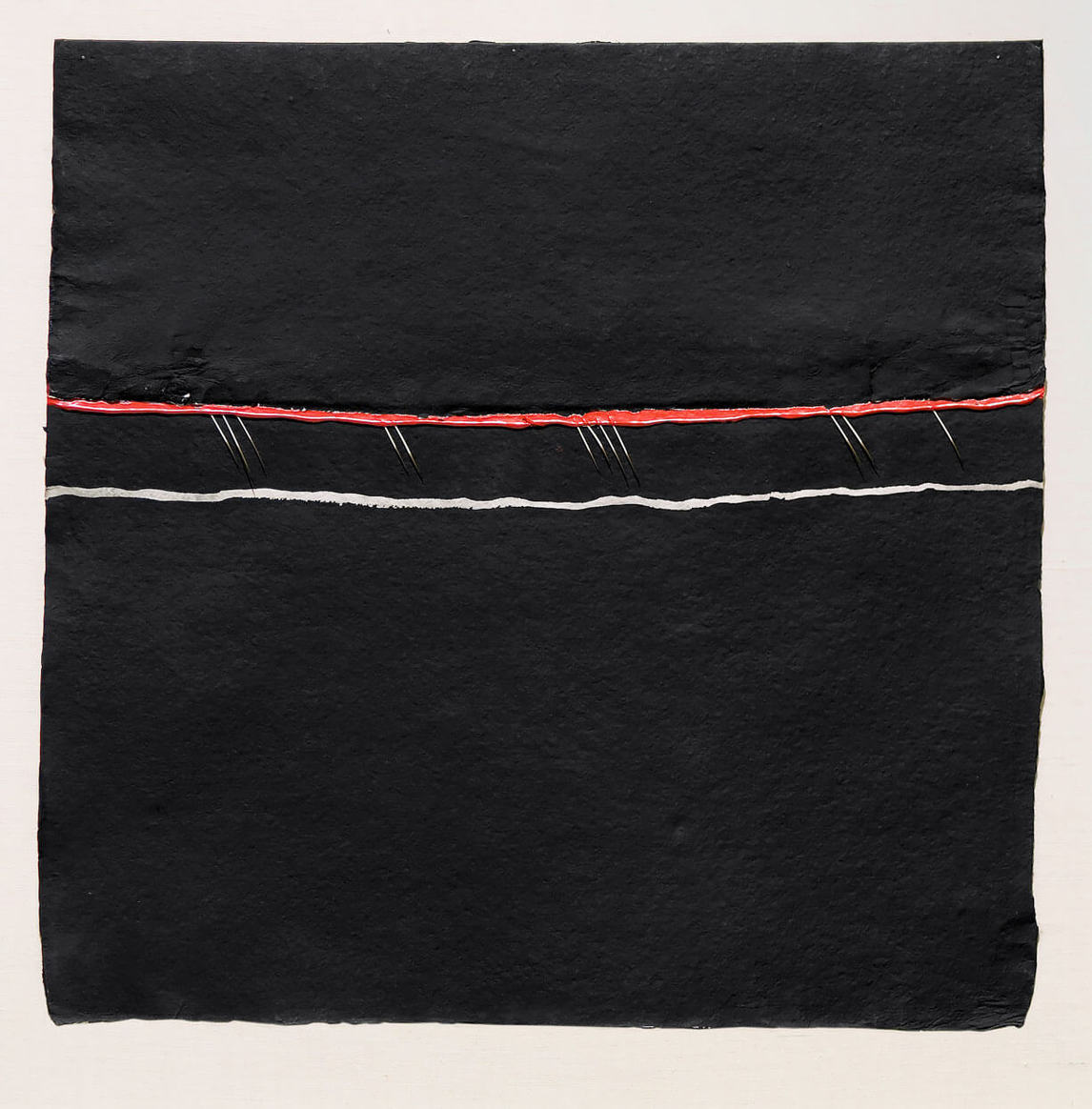

Many of Houle’s paintings have been depictions of a parfleche, a traditional travel pouch rectangular in shape with a fold that represents the meeting of land and sky. Houle imbues his parfleche-inspired artworks with private, personal meaning by incorporating into them codified elements known only to him. He also includes references to cultural objects and symbols. For example, in Parfleches for the Last Supper, Houle used handmade paper, folded the top portion over to resemble a parfleche and after painting the surface physically joined the fold with penetrating diagonal stitches of porcupine quills like those that decorated Northeast Indigenous clothing and containers. In Parfleches for the Last Supper #5: Philip, equal-armed yellow crosses float across a vibrant red colour field. Though resonant with the Christian cross, this Saulteaux cross references the morningstar in the cosmos and the colour yellow refers to the Sun Dance ceremony.

In 1990, when Houle began experimenting with steel, he produced Innu Parfleche using pieces of scrap iron that Houle asked the late and legendary programmer of the Toronto International Film Festival, David Overby (1936–1998), to drive over repeatedly with his car to alter its shape. The work honoured the Innu people of northern Quebec who, in the late 1980s, were engrossed in struggles to prevent military flight manoeuvres over their territory. Here the form of the parfleche functions as a metaphor for resistance. In paintings such as Parfleche for Norval Morrisseau, 1999, and Parfleche for Edna Manitowabi, 1999, Houle specially chose his colours to symbolically represent the two influential artists and, in abstract terms, invokes the form of the traditional object in homage to them. In Houle’s words, “What better way to recognize people who have played a significant role in my life?”

From Painting to Installation

While painting has been and remains a mainstay of Houle’s work, he began making installations in the mid-1980s as a means of creatively expressing his political ideas, as can be seen in Everything You Wanted to Know about Indians from A to Z, 1985. Here, by suggesting the common, accessible form of a library shelf, Houle raises awareness of the inappropriate documentation and appropriation of Indigenous names in books. For Houle the process of a work’s creation combined with the placement of a work—in this case in an art museum—is a site of political and cultural change.

Houle is an artist who understands sacred space, and his work soon expanded into site-specific installations that focus on sovereignty. With reclamation as his objective, he treats his installation sites as landmarks where knowledge exists. Zero Hour, his first site-specific installation, was part of the 1989 exhibition Beyond History at the Vancouver Art Gallery. The work marked the forty-fourth anniversary of the first nuclear explosion in the New Mexico desert, its intent an ominous warning to humankind. An inscription featured on a black wall, “For as long as the sun shines, the rivers flow, the grass grows …,” is a well-known, much quoted phrase that once referred to the possibility of the harmonious co-existence of colonizers and First Nations peoples for time eternal.

In the history of Canada numerous documents tell stories of conquest and expansion, trade and development, in which colonial aspirations harmed countless Indigenous peoples. First Nations have been excluded from the telling of such history. Houle’s impeccable research into official and unofficial documents involves the extensive recovering of information related to a true history of First Nations. For his site-specific work, he begins with research on the location and its previous history, whether it be of a museum, government institution, or particular piece of land.

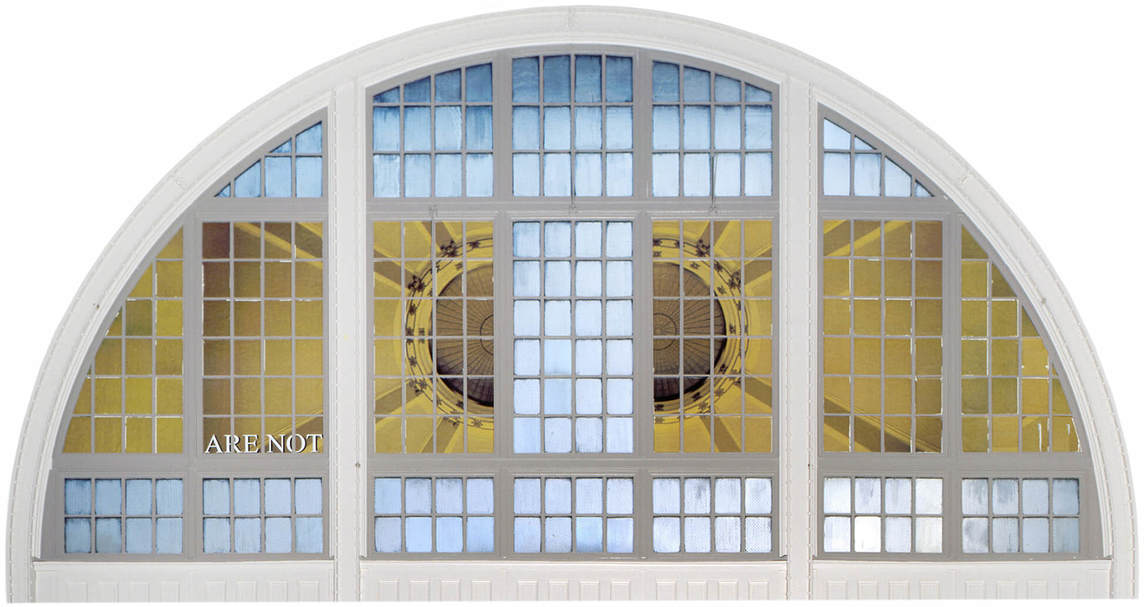

For his exhibition Sovereignty over Subjectivity at the Winnipeg Art Gallery in 1999, Houle produced three site-specific projects that year, all associated with history and sovereignty: Morningstar at the Manitoba Legislative Buildings, These Apaches Are Not Helicopters at the VIA Rail train station, and Gambling Sticks, a permanent installation on a sacred site where the Red and Assiniboine rivers meet in Winnipeg and a place where, historically, Indigenous people would rendezvous, camp, and trade goods. In Gambling Sticks, Houle visually marked the significance of the place with twenty-one enlarged bronze replicas of Tahltan gambling sticks. Historically, gambling sticks were used to pass the time when First Nations people met at the river junction and were not directly occupied with trading. By planting these sticks in this place, Houle symbolically honoured the location and turned it into a spiritual space that grounds his cultural identity and personal connection to Manitoba.

Between 1994 and 1996, Houle undertook several design works with the City of Toronto’s Department of Urban Design, City Planning. After doing extensive archival research, Houle elicited ancient voices from the written records, materializing them in the works. The resulting permanent public art installations are statements about the ownership of memory and affirm that which historically existed—waterways, frogs, and canoes, for instance—in what are now cityscapes. Alongside York Street in an area that connects Toronto’s railway station and subway loop with the shore of Lake Ontario is a pedestrian walkway. Houle marked a route to the lake over this land, which fills in an area that used to be water. Another of Houle’s installations traces the path of Garrison Creek, which now flows underground through a series of storm sewers. In both works, Houle arranged cast bronze animals set into sidewalks among the neighbourhood streets and parks.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements