As an artist, curator, and educator, Robert Houle has made an indelible impact on Canadian and Indigenous art. For four decades he has been reconciling and synthesizing contemporary art trends and Anishnabe traditions: encouraging a renewed vision of the world that includes cultural memory; exposing and challenging the government on political issues affecting Indigenous peoples, including land rights and the rights of Indigenous art and artists; and decolonizing the museum and the self.

The Land

The importance of the land, its sacredness and history, is a thread that runs through Houle’s work. Most of his artwork emphasizes how land is the key element in understanding one’s history and future path, and in shaping his Anishnabe identity. For Houle, the loss of ancestral land has been a cause of a grave identity crisis for generations of First Nations. His own connection to a particular geography is evident in Muhnedobe uhyahyuk (Where the gods are present), 1989, in which he renewed his relationship with the prairie landscape and reclaimed it for his people in Sandy Bay, Manitoba.

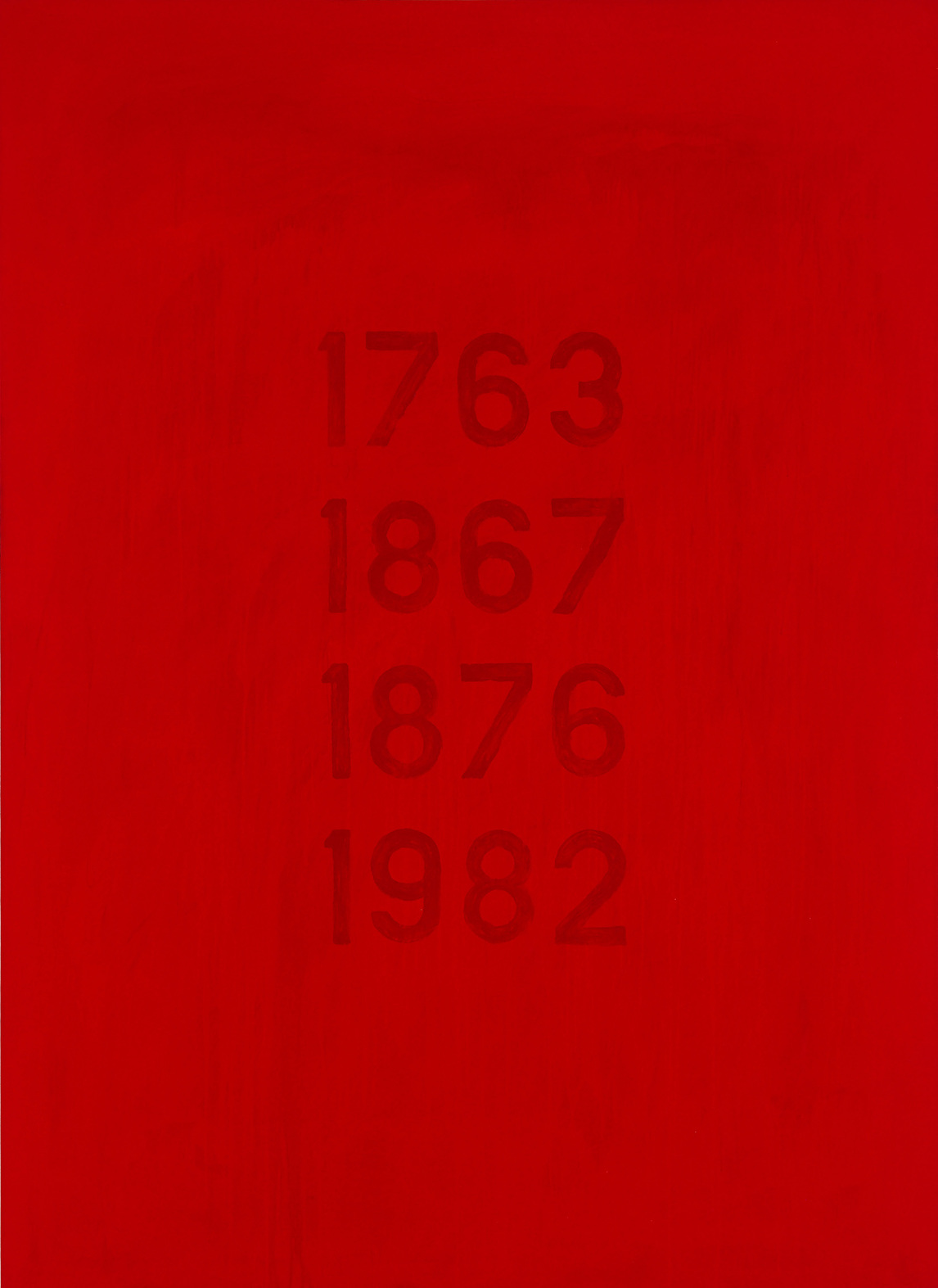

The legacy of European colonization has rendered First Nations peoples alienated in their own territories. Houle believes that places “can be socially and politically constructed and this construction is about power.” His work frequently emphasizes political issues related to land, visually asserting First Nations’ historic and legal connection to it, as in Premises for Self-Rule, 1994. Aboriginal Title, 1989–90, is another such example. This work presents four crucial dates marking years when legislation was passed that served as legal precedents for First Nations’ rights and freedoms regarding land: 1763, 1867, 1876, and 1982.

In the late 1980s and 1990s, political events across Canada galvanized Indigenous solidarity and aroused activism that would resonate throughout the decades. It was a charged period, when First Nations articulated clear positions regarding land claims, human rights, self-determination, and self-government, including the “no” vote to the Meech Lake Accord by Elijah Harper, a Cree member of the Manitoba Legislative Assembly.

The tension was exacerbated by controversies that also shook up the museum world. For instance, in connection with a land dispute, the Lubicon Lake Nation boycotted the exhibit The Spirit Sings: Artistic Traditions of Canada’s First Peoples, organized by the Glenbow Museum, Calgary, in conjunction with the 1988 Winter Olympics. The show included historical Indigenous objects previously removed from their communities without permission and loaned to the Glenbow from national and international ethnographic and anthropological collections. At the same time, Indigenous artists across Canada were vocalizing the ongoing exclusion of their art from the majority of mainstream art institutions. Boycotts, demonstrations, media storms, and protest art had a profound impact on the content of—and contexts for—Houle’s work.

In his first solo exhibition in Montreal in 1992, at articule, Houle premiered a significant multimedia installation, Hochelaga, which was a testimony to his aesthetics and social commitments—and to land reclamation. The month-long exhibit confronted the public with work that challenged Western/European notions of ownership of the land and highlighted the struggle of First Nations for independence, promoting their sovereignty. The title piece, for example, used images and text to address First Nations’ autonomy from a local perspective. Yellow vinyl letters on a white surface spelled out the names of Iroquoian communities from the past and present, such as the Mohawk locales of Kanesatake, Kahnawake, and Akwesasne, which have been at the centre of sovereignty disputes with municipal, provincial, and federal governments. By linking these communities to Hochelaga, the ancient Haudenosaunee settlement that was located on the island of Montreal, Houle connected them to a long history associated with the land and supported their right to independence.

Several of Houle’s works between 1990 and 2000 were political responses to contemporary land disputes between First Nations and the Canadian government, reflecting what he has been stating and painting most eloquently for years: that history has been a continuous process of limiting power and land for his people. Kanehsatake X, 2000, and Ipperwash, 2000–1, are two works that respond to the Oka Crisis—when Mohawks protested the encroachment of a golf course into their traditional territory and burial ground in Quebec—and to events at Ipperwash, Ontario—a land dispute during which Ontario Provincial Police shot and killed an unarmed Ojibwa protestor, Dudley George. Both Kanehsatake X and Ipperwash juxtapose canvas, panel, and text to denote ownership; both feature digitized photo images of arrowheads buried in cautionary red and yellow stripes that mimic urban warning signs. The canvases are painted in cobalt green and cobalt dark green—referring to the golf course at the centre of the Oka dispute and the pines that lined the roads. They are like palisades and protect the ancestors, who are symbolized by the arrows. In Kanehsatake X there is also a blue panel, an emotional colour that for Houle relates to his ancestry and to the power of water.

Houle’s curatorial work has also underscored the relationship between land and Indigenous peoples of Turtle Island (North America) as one with an ancient history. In 1992 official celebrations on both sides of the Atlantic marked the 500th anniversary of the arrival of Christopher Columbus in the Americas. The celebratory spirit was not shared by Indigenous peoples who reacted against five centuries of oppression and exclusion. During that year Houle co-curated Land, Spirit, Power: First Nations at the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa. While a simultaneous exhibition by the Society of Canadian Artists of Native Ancestry (SCANA) and the Canadian Museum of History in Gatineau, titled Indigena: Perspectives of Indigenous Peoples on Five Hundred Years, focused on a critique of colonial history, Land, Spirit, Power highlighted land as a spiritual and political legacy.

Houle’s research for the exhibition prompted its focus on land, a subject consistent in his artistic production but that he addressed in his curatorial work for the first time here. He had interviewed Indigenous artists in the United States and Canada, including Rebecca Belmore (b. 1960), James Luna (1950–2018), Kay WalkingStick (b. 1935), and others. In the article “Sovereignty over Subjectivity,” he describes the experience: “Criss-crossing this vast continent, one thing became evident: the persistent impact and ever-changing physicality of the landscape. And among these artists, regardless of where they lived, there existed some common relationship to the surrounding space and in the sanctifying of territory.” In his catalogue essay “The Spiritual Legacy of the Ancient Ones,” Houle recognizes the artists’ connection to antiquity, giving a context to the legacy left to them; he asserts an abiding conviction about First Nations’ inherent right to the land that their ancestors enjoyed and respected.

Revisioning Representation

Through his curatorial work and artistic projects, Houle has challenged colonialist notions of Indigenous art as primitive and as an extension of ethnological collections. Art historian and curator Ruth B. Phillips notes that the Indigenization of Canadian museums was shaped by two consequential events. First, the Indians of Canada pavilion at Expo 67 in Montreal critiqued conventional Indigenous-settler narratives that positioned the colonizer as civilized and Indigenous peoples as a vanishing race or one in need of assimilation. Second, because of the widespread protest of Indigenous leaders and communities—a protest that Houle participated in—the Government of Canada was forced to withdraw its 1969 White Paper (the “Statement of the Government of Canada on Indian Policy”), which intended to make all peoples of Canada heterogeneous and which would impact First Nations cultural and land rights.

Houle’s resignation from the National Museum of Man in Hull (now the Canadian Museum of History) helped force museums and public art galleries to change their collection and exhibition practices to include Indigenous voices. The exhibition Land, Spirit, Power, 1992, for instance, while not eschewing the political, was first and foremost about art. It revealed the two imperatives to which contemporary Indigenous artists were responding: the call of a moment in history for cultural and political intervention and the demand for serious acceptance of the aesthetic value of contemporary Indigenous art. The National Gallery of Canada embraced this and began integrating the acquisition of work by Indigenous artists into the permanent collection alongside other contemporary Canadian and international artists.

As well Houle has long been committed to repatriating historic objects from ethnographic museums and correcting inappropriate presentations of them. Through his visual art, Houle amplified this undertaking in a 1993 exhibition at Carleton University Art Gallery, Ottawa: Kanata: Robert Houle’s Histories. At the National Gallery of Canada in 1992, Houle had come across an interpretative area near the installation of The Death of General Wolfe, 1770, by Benjamin West (1738–1820). He discovered that the gallery had borrowed, from the British Museum, sacred Indigenous objects that were used as studio props by West for his fictional painting. In his Carleton University exhibit, Houle parodied the National Gallery’s treatment with two works: Contact/Content/Context, 1992, which displays his own moccasins in a Plexiglas box that Houle placed near Kanata, 1992, a painting that comments on West’s incorrect portrayal of a Delaware warrior in bare feet. Houle’s installation questioned the museum’s representation of Indigenous history by mimicking its construction while using his own language and personal objects. He thereby formulated a different history—one that undermines a Western perspective limited by self-serving biases of colonialism.

Such politically charged work of Houle’s has inspired a new generation working in performance, video, new media, and photography. Houle’s friend and colleague Bill Reid (1920–1998) revitalized traditional Haida art and mentored Robert Davidson (b. 1946). Shelley Niro (b. 1954), Greg Staats (b. 1963), and Jeff Thomas (b. 1956) have taken on issues surrounding Indigenous identity through their works. As well Houle provided the foundation for curators—including Greg Hill (b. 1967), Gerald McMaster (b. 1953), and Wanda Nanibush (b. 1976)—to revisit collection strategies and position Indigenous art within contemporary art practice.

Cultural Appropriation

Robert Houle’s work has deepened the understanding of cultural appropriation in museums and art galleries, and in a broad spectrum of institutions and disciplines (for example, advertising) invested in maintaining false notions of Western and Indigenous cultures. Cultural appropriation refers to a power dynamic in which members of a dominant culture take elements from a culture of people who have been systematically oppressed. For Houle, cultural appropriation is about Western culture’s erasing and ignoring of Indigenous voices by misrepresenting its cultures. Running parallel to an entire history of incorrect cultural projections in paintings, photographs, and written accounts by Europeans in North America is a lack of First Nations’ representation in contemporary culture. He writes, “Exclusion from Western representation is deeply rooted in and even protected by a structure that authorizes and legitimizes certain representations while blocking, prohibiting or invalidating others.”

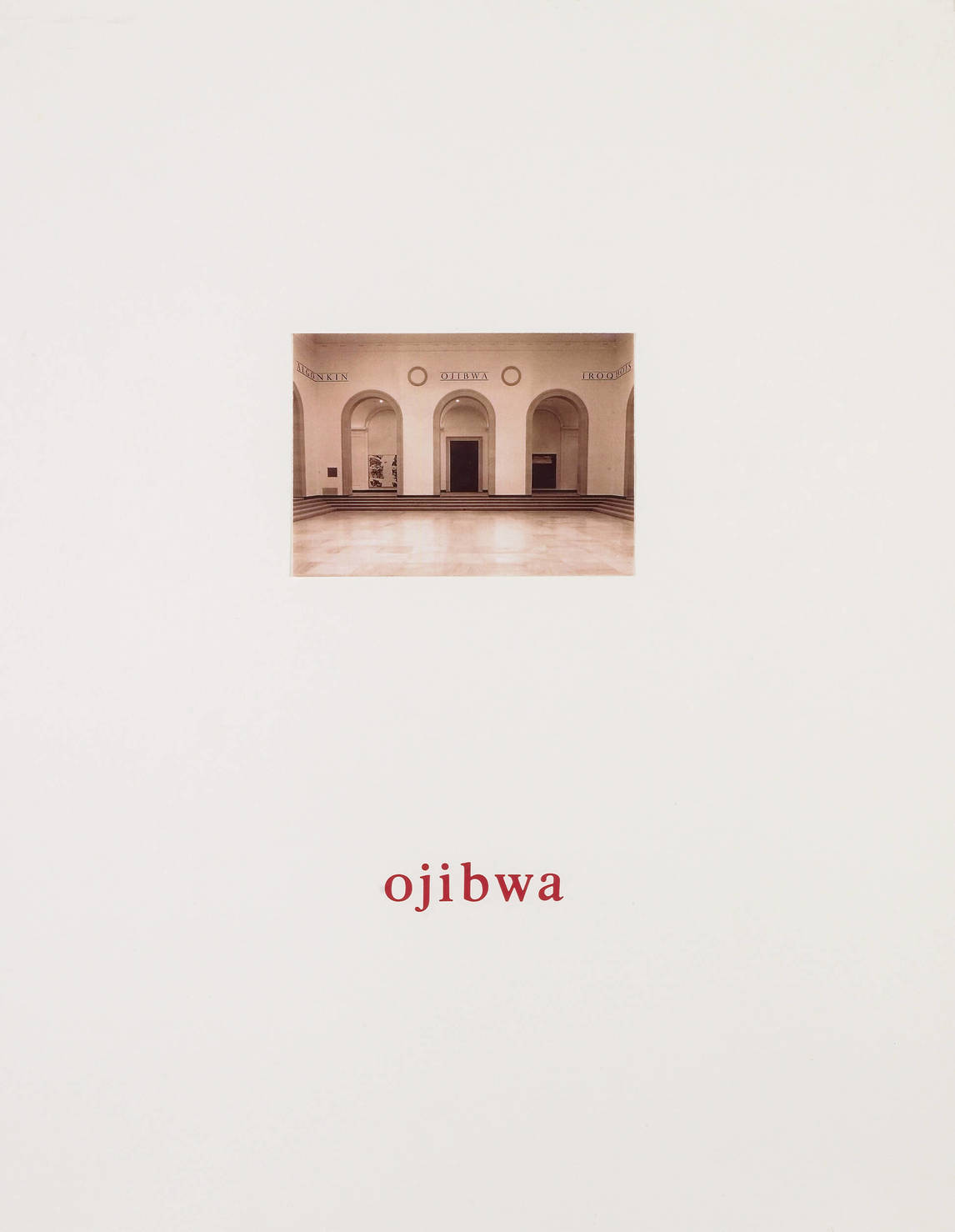

In 1985 Houle’s encounter with an installation by German artist Lothar Baumgarten (b. 1944) at the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO), Toronto, brought the issue of cultural appropriation to the fore. The AGO invited Baumgarten to produce a site-specific work for Walker Court as part of the exhibit The European Iceberg: Creativity in Germany and Italy Today. Baumgarten created Monument for the Native People of Ontario, 1984–85, meant to pay homage to eight nations of the province. Their names were printed in large Roman type on the walls surrounding the court at the centre of the AGO. Houle was jolted by the lack of research in documenting the names. Some were misspelled, and linguistic groups, regions, tribes, and bands were intermingled without distinction. Also disturbing was Baumgarten’s appropriation of the right to document the names. About the installation, Houle writes, “It is a beautiful work, styled as a tribute, but the human drama it presents is unfortunately simply a program of romantic twentieth century anthropology … a transgression of the spiritual integrity of those whose names he has written is to point out that their oral tradition was violated.”

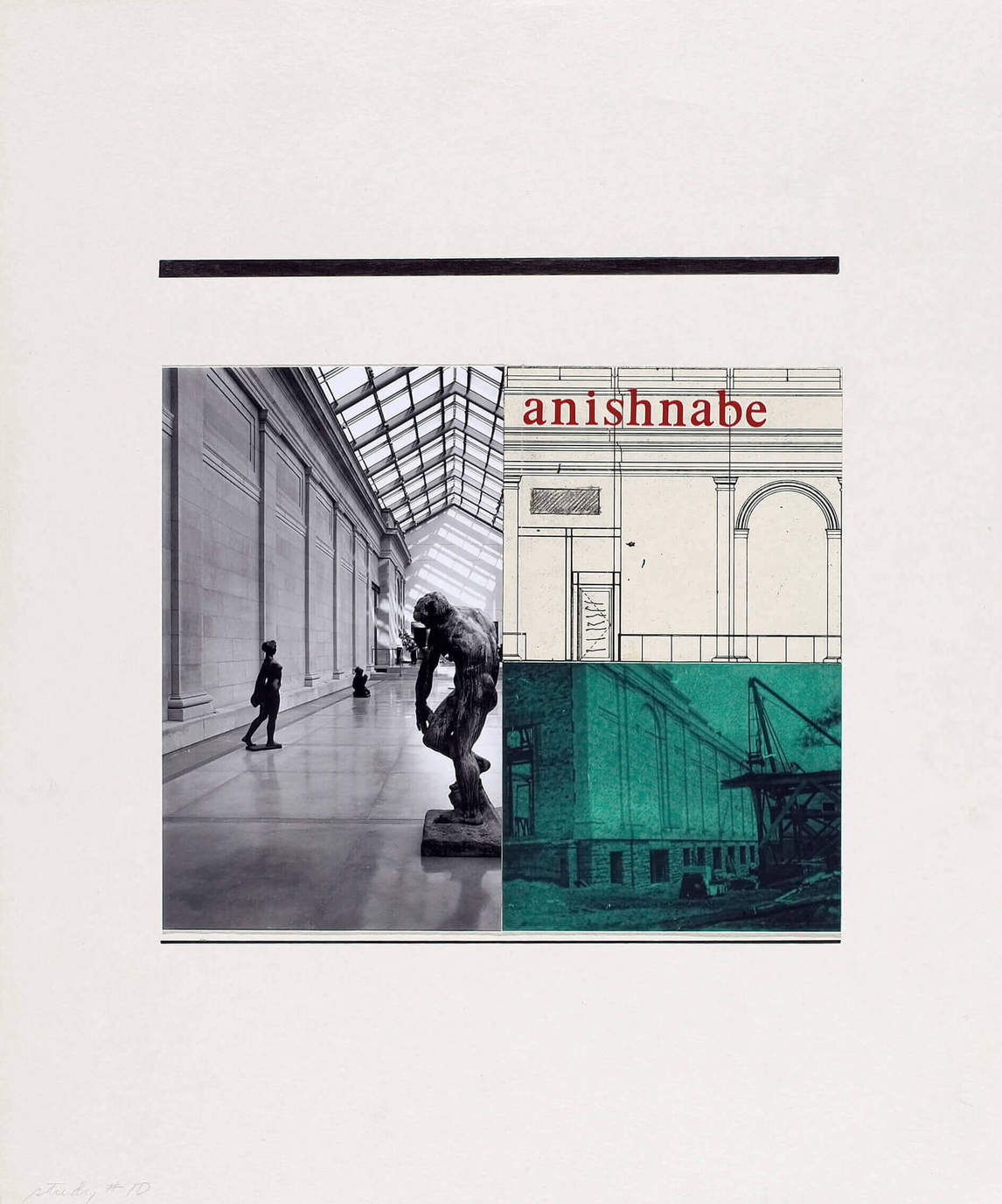

When Houle responded to Baumgarten’s installation with Anishnabe Walker Court, 1993, he re-appropriated the German artist’s tribal names, placing them in quotation marks and re-inscribing them in lowercase on the outer wall surrounding Walker Court. Also featuring photographic documentation of the changes to Walker Court over the years, the work comments on the histories of change and memory and how museums such as the AGO, as colonial institutions, are prone to improper memorialization, as in the case of Baumgarten’s installation incorrectly displaying past images and icons of Ontario Native culture.

Houle frequently selects words from archival documents, implements of war, and consumer goods to highlight how imagery from Indigenous cultures has been exploited for commercial or military enterprise. In the mid-1990s, Houle began to research the commodification of names of famous chiefs and tribes. These Apaches Are Not Helicopters, 1999, for instance, examines the appropriation of Indigenous names as commodities and emblems of war. A site-specific work installed in four half-moon windows at Winnipeg’s VIA Rail train station, the work presented an imaginary homecoming for Chief Geronimo (1829–1909) and his warrior Apaches. Geronimo was famous for resisting colonization and taking a stand against the U.S. government for almost twenty-five years. Houle strategically placed an enlarged archival photograph of Geronimo on the south window of the station, signalling the customary direction of the arrival of Apaches. The final image, on the east window, was of the McDonnell Douglas Apache helicopter.

Similarly, the legacy of Chief Pontiac (1720–1769), an important Odawa warrior chief and diplomat who worked to unite the Algonquian-speaking nations of the Great Lakes area with those of the Ohio and Mississippi Valleys, appears in Houle’s work as interventions to restore Pontiac’s identity. Chief Pontiac is a symbol of strength and was murdered for financial gain; centuries after his death General Motors named a car after the legendary hero. Houle sees this as white capitalist supremacy appropriating the power associated with the chief. Houle’s work Kekabishcoon Peenish Chipedahbung (I Will Stand in Your Path Till Dawn), 1997, draws on Pontiac’s history, image, and promise of endurance. Houle assembled reproductions of thirty-six twentieth-century advertisements for various automobiles on which he overlaid vinyl lettering that spells out “Pontiac” and the names of the Algonquian nations, thereby reclaiming Indigenous history and heritage.

Decolonization

Houle’s intentions focus on forcing viewers to reconsider the colonial past. His artistic process of dealing with the legacy of colonialism, including his time at residential school, incorporates varied forms of both personal and collective remembering through drawing and painting, and sometimes strategically includes postmodernist approaches.

The production of two major works addressed the legacy of the residential school system: Sandy Bay, 1998–99, and Sandy Bay Residential School Series, 2009. The latter recalls dark experiences the artist had at residential school. In creating the drawings, he visually rendered memories associated with the experience that came to him through dreams:

I had a horrible, vivid dream about an incident that had happened to me that I had completely forgotten.… So I … decided once and for all that I was going to deal with this…. After each drawing I would be totally emotionally exhausted…. But I would get a good sleep and the next morning I would begin again.

The work’s creation was a personal decolonization: “For the first time I began to talk to myself when painting. My body would decolonize itself with my voice.”

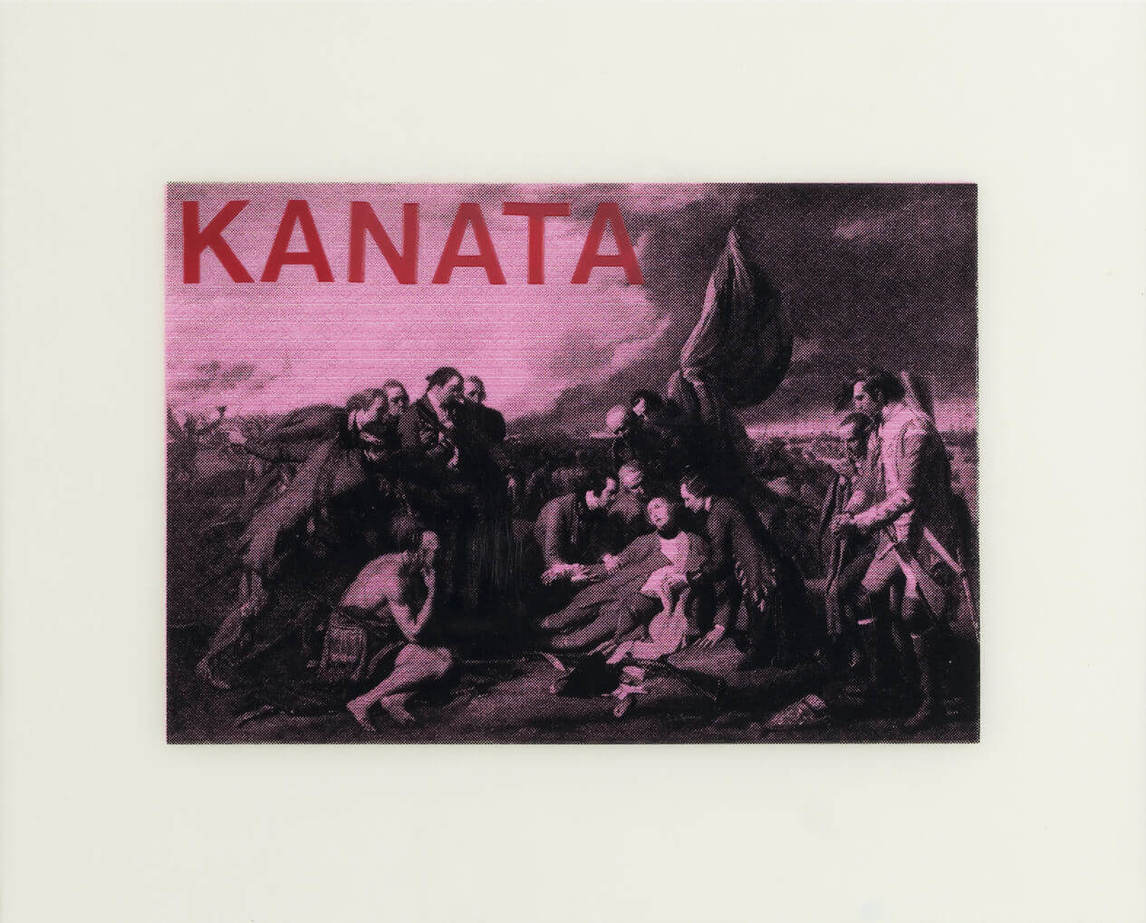

In Kanata, 1992, Houle visually asserts an Indigenous account of a political history to invoke another history radically different from the one painted by Benjamin West in The Death of General Wolfe, 1770. In his work, Houle “bleached” the colour out of the European figures copied from West’s painting and vivified the warrior in colour, thereby reversing the power relations. The work was “contemporary with parallel constitutional deliberations in which the presence of Native Canadians had been looming larger as they [sought] control over their destinies.” By appropriating West’s painting, Houle avowed his right to depict the First Nations experience and revised colonial history, positioning First Nations as “founding nations” of Canada alongside the French and English.

A recent work by Houle, O-ween du muh waun (We Were Told), 2017, further challenges the long history of colonial assumptions about the place of Indigenous peoples within Confederation. Commissioned by the Confederation Centre Art Gallery in Charlottetown, the painting offers a revised vision of Canada’s sesquicentennial. Elaborating on Kanata, Houle focuses his attention once again on the Delaware warrior from The Death of General Wolfe, only this time the warrior is painted in oil (as opposed to coloured Conté), seated alone, in the same location where Wolfe died in West’s painting, facing east on the Plains of Abraham. By eliminating all other figures from the composition, Houle effectively erases the colonizer and addresses current political and cultural issues. As Canada seeks reconciliation with First Nations, Houle points to a history that predates the European invasion of the land. “The 150 idea [celebrations to acknowledge the 150th anniversary of Canadian Confederation] was not an issue for me, but rather a correction to clarify that my sense of country dates back further than 1867,” Houle offered. “Our friendship and numbered treaties are also preceded by the presence of our ancestors going back millennia.”

Impact

Robert Houle has perforated the space of a Eurocentric art history in Canada and offered other histories apart from a European lineage. Using modern, postmodern, and post-colonial critiques in his art, curatorial work, and teaching, he has broken the shackles of colonialism to recover and engage artists of the past—from Benjamin West and George Catlin (1796–1872) to Barnett Newman (1905–1970)—in dialogues that re-contextualize the present.

As the first curator of contemporary Indian art at the National Museum of Man, in 1977 Houle’s critique of the collection and exhibition practices there raised awareness of how Canadian museums and art galleries were mistreating the work of Indigenous artists. He advanced the belief that their art should be seen foremost in art galleries and not in the context of anthropological or ethnographic artifacts. Despite resistance from museum authorities, he proposed purchases of work by Carl Beam (1943–2005) and Bob Boyer (1948–2004), among others. After his resignation, he pursued independent curatorial work and was responsible for two landmark exhibitions—New Work by a New Generation, in 1982 and Land, Spirit, Power, in 1992—both of which foregrounded Indigenous art within a contemporary milieu.

As a curator and a creator, Houle was part of this important group of Indigenous artists emerging as distinct, relevant creators within the Canadian art landscape. In New Work by a New Generation, and in his accompanying catalogue essay, for instance, Houle built a case for Indigenous artistic practice presenting fresh and contemporary artwork. He showed the capacity of these artists to synthesize their backgrounds, each standing at the edge of the mainstream or between it and their community. This inspired younger generations of Indigenous artists, including Bonnie Devine (b. 1952), Rebecca Belmore, and Shelley Niro. Houle was never against tradition but was among the first to herald Indigenous work as sophisticated enough to warrant attention as mainstream art.

That Houle changed the landscape of Canadian art is undeniable. Today, art museums and public art galleries are hiring Indigenous curators; Wanda Nanibush holds a position at the Art Gallery of Ontario and Greg Hill at the National Gallery of Canada. Contemporary Indigenous artists are included in permanent collections and aligned with contemporary artists and movements rather than treated as separate entities. There is a conscious move on the part of institutions towards decolonizing spaces and readdressing collection policies. Indigenous artists are now exhibited alongside other artists of different backgrounds and countries. Amid all these positive changes, Houle led the way, his work a part of rewriting art and cultural history.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements