From growing up in Sandy Bay First Nation / Kaa-wii-kwe-tawang-kak and attending residential school to pursuing extensive academic studies and becoming an internationally recognized artist, Robert Houle (b. 1947) has played a pivotal role in bridging the gap between contemporary Indigenous art and the Canadian art scene. As an artist, curator, writer, educator, and critic, he has created change in museums and public art galleries, initiating critical discussions about the history and representation of Indigenous peoples.

Early Years

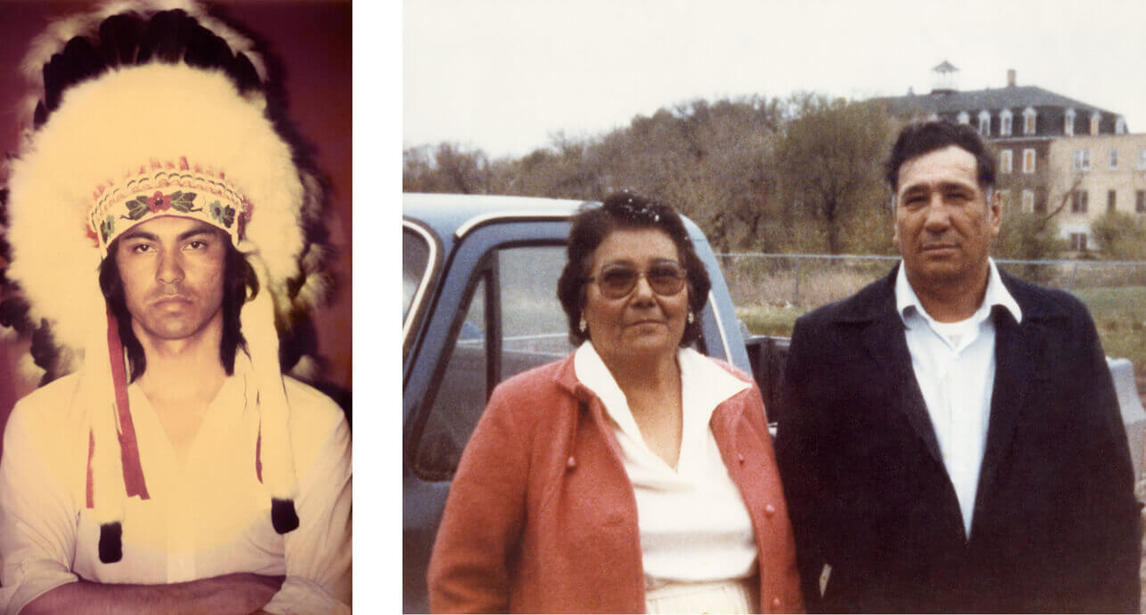

Robert Houle was born to Gladys and Solomon Houle on March 28, 1947, in St. Boniface, Manitoba, the eldest of fifteen children. His early childhood was spent in the extended-family home at Sandy Bay First Nation, where he was immersed in Saulteaux culture, spoke Saulteaux, and witnessed traditional ceremonies. Houle’s family belongs to the Plains Ojibwa, or Anishnabe Saulteaux, who live along the western sandy shores of Lake Manitoba.

Like many children of his generation, Houle was forced to go to a Catholic mission–run residential school for grade school and high school, where he was removed from both the Saulteaux language and its spiritual traditions. From grades one to eight, Houle attended The Oblates of Mary Immaculate and Sisters of St. Joseph of St. Hyacinth School in Sandy Bay. Residential schools were part of the Canadian government’s program to “assimilate” Indigenous populations. The great damage these schools have done to Indigenous peoples, their communities, and their culture has been widely documented. Houle’s years at residential school would have a profound effect on him and his career. Referring to his Roman Catholic upbringing, he stated, “The Bible is the single most important cultural influence on my shamanistic heritage.” Christianity combined with his Saulteaux heritage would become integral to his personal and artistic identity.

Houle’s early educational experiences in Sandy Bay were unpleasant. He was not allowed to paint sacred objects, such as warrior staffs, or experiences from his own culture, nor to speak to his sisters who also attended the school. It was difficult for him to look out the classroom window and see his family’s house yet not be permitted to go home after school. He regularly joined his family during their annual Sun Dance ceremony to mark the summer solstice; however, after Houle returned to school, the priest would force him to go to confession and repent for worshipping false gods. This difficult part of his life would later inform two emotionally charged artworks: Sandy Bay, 1998–99, and Sandy Bay Residential School Series, 2009.

In 1961 Houle moved to Winnipeg to attend the Assiniboia Residential High School run by the Oblates and Grey Nuns. He has happy memories of his high school years—being in a co-ed classroom, playing football and hockey, and being the editor of the high school yearbook and newspaper. Although art classes were a small part of the curriculum, he was introduced to art practice and his teachers recognized him for his artistic gifts. At the school he won a drawing competition that allowed him to take extracurricular art classes. Houle’s high school years coincided with a change in Canadian politics surrounding First Nations’ treaty rights. Reading the Indian Act was a mandatory part of his studies in Canadian history and made him acutely aware of the issues facing his people. On March 31, 1960, under Prime Minister John Diefenbaker’s tenure, portions of the Canada Elections Act were repealed to grant a federal vote to First Nations peoples, without loss of their status. After he graduated Houle was able to vote.

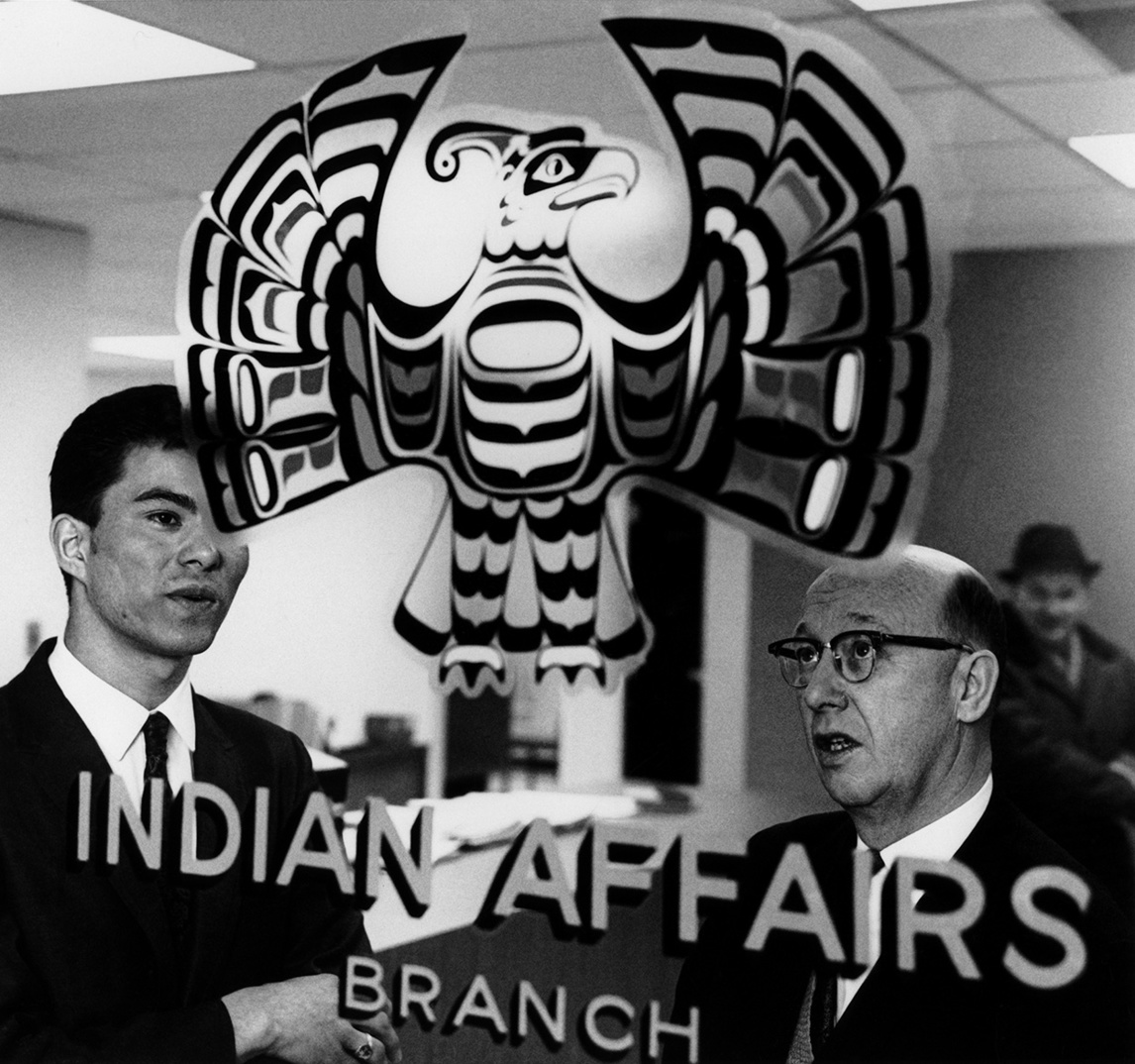

Following high school Houle attended the Jesuit Centre for Catholic Studies, St. Paul’s College, at the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg, for one year. Education was valued in Houle’s family: “My parents encouraged us to attend university. They felt that a solid education would enable us to be more self-sufficient in our future endeavours.” Houle enrolled in a degree program at the University of Manitoba and in the summer of 1969 worked as a summer student at the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development (now Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada) in Ottawa. There he joined First Nations’ protests against a federal government policy paper known as the 1969 White Paper, which called for an end to federal fiduciary responsibility for First Nations’ special status. Many Indigenous peoples viewed the paper as an extension of the federal government’s assimilationist policies, and the Canadian government withdrew it in 1970.

Studies in Art

While at the University of Manitoba, Houle concurrently began studies at McGill University in Montreal. In 1972 Houle earned a degree in art history from the University of Manitoba, following which, to improve his skills in drawing and painting, he travelled from Montreal to Austria to attend the Salzburg International Summer Academy. He then moved to Montreal to complete his bachelor of education with a major in the teaching of art from McGill and also taught art at the Indian Way School, located in a longhouse in Kahnawake, across the St. Lawrence River from Montreal. He completed his teaching degree in 1975. Houle stated, “It was an aspiration of mine to be an art teacher as well as an artist. When I decided to be an artist, my mother told me to paint only what I know.” After receiving his certification as an art specialist, Houle taught a grade five art class for one year, following which he instructed at a Catholic school in Verdun (a borough of Montreal) until 1977.

At McGill Houle had received formal education in studio work. He also audited studio classes at Concordia University with the Quebecois hard-edge painter Guido Molinari (1933–2004). While researching art history, Houle became interested in the work of Piet Mondrian (1872–1944), Barnett Newman (1905–1970) and the New York School of Abstract Expressionism, and Jasper Johns (b. 1930). He focused mostly on European art, ranging from pre-Columbian sculpture and Greek and Roman art and archaeology to twentieth-century European painting. While studying the Romanticists in an art history class, he came across the work of French painter Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863) and, in the artist’s journal among sketches of Indigenous subjects, a statement referring to the Ojibwa as “nobles of the Woodlands.” Decades later, Houle would reference Delacroix in a multimedia installation, Paris/Ojibwa, 2010.

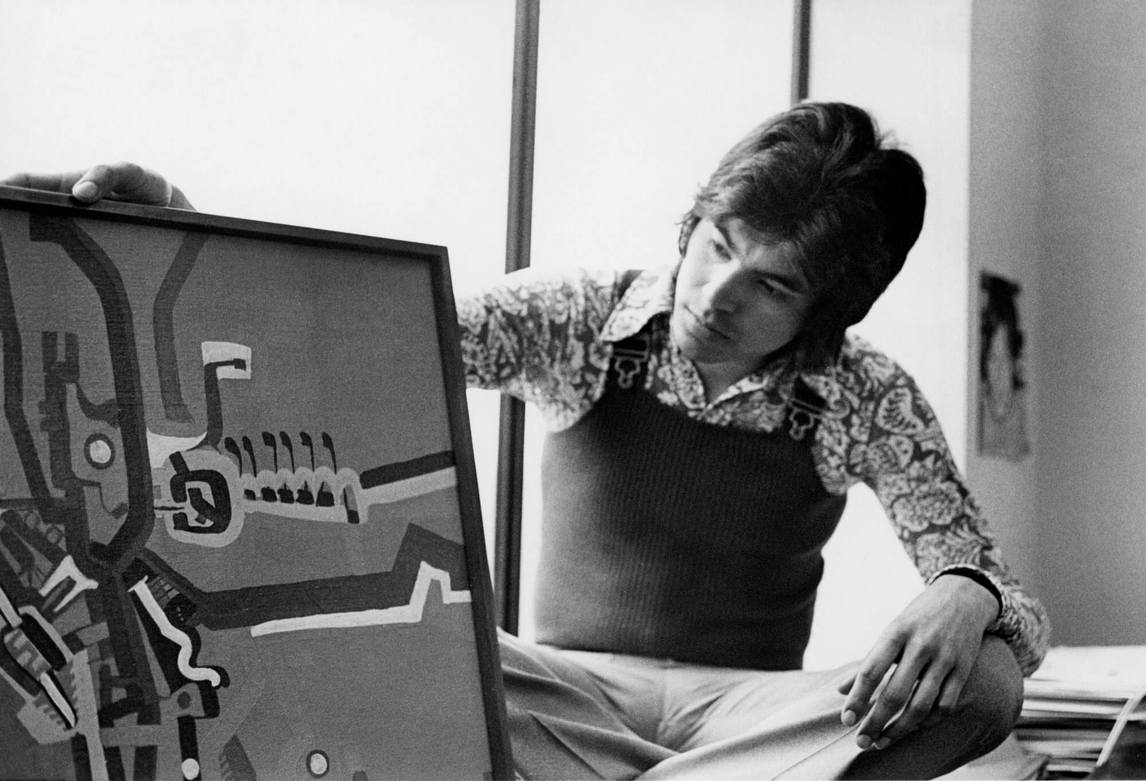

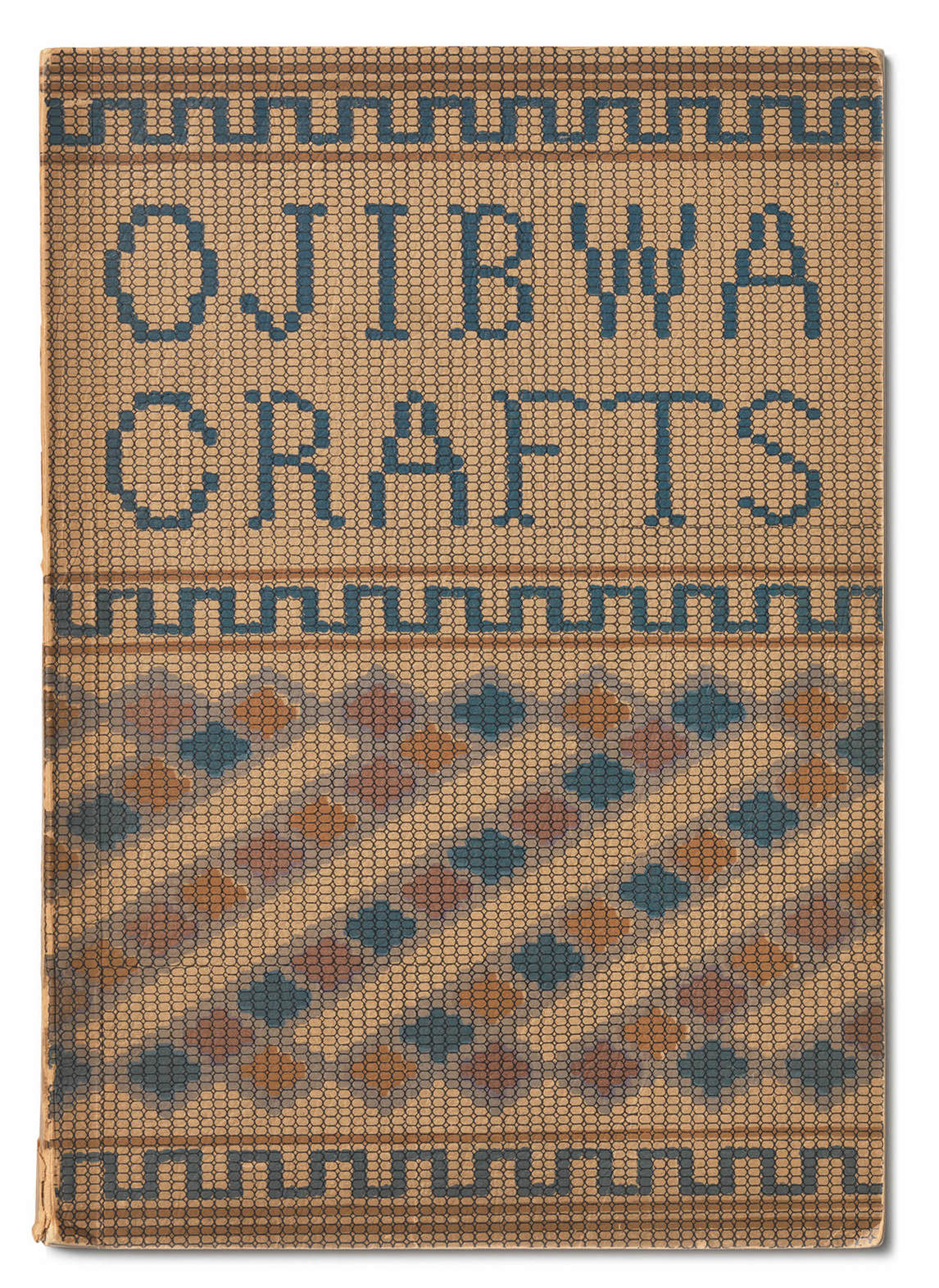

During the early 1970s, Houle produced abstract geometric paintings inspired by Ojibwa designs published in Carrie A. Lyford’s book Ojibwa Crafts (1943). Works such as Red Is Beautiful, 1970, and Ojibwa Purple Leaves, No. 1, 1972, are indicative of his early style. Houle stated:

I found the geometrical patterns represented in the book had a spiritual connection to traditional ritual and ceremonial objects, and this in turn led to a series of geometric acrylic paintings I produced inspired by love poems written by a friend, Brenda Gureshko, that were purchased by the Department of Indigenous and Northern Affairs.

Epigram the Shortest Distance, 1972; Wigwam, 1972; and The First Step, 1972, are from the love poems series and show his early dedication to creating abstract works connected with Indigenous traditional geometric designs.

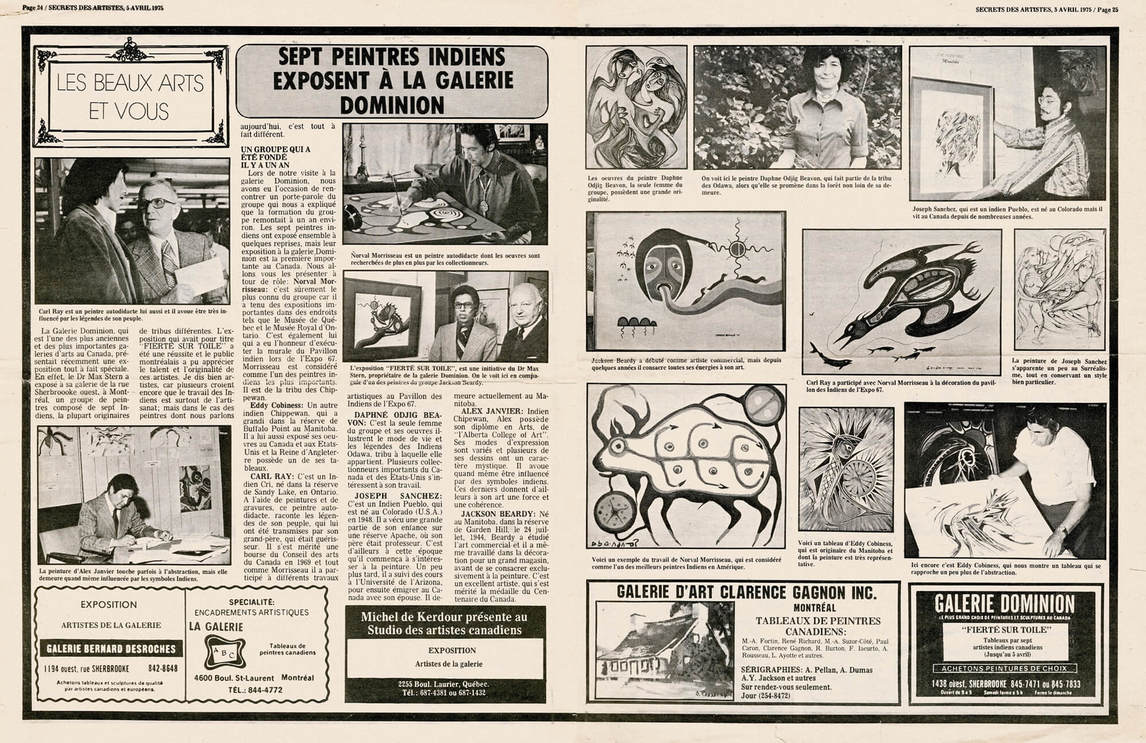

Houle’s time in Montreal was in the wake of the October Crisis of 1970. It was a period of political unrest regarding Quebec sovereignty, during which the city was also experiencing a surge of activity in contemporary visual and performance art. In 1975, while still at McGill, Houle saw the group exhibition Colours of Pride: Paintings by Seven Professional Native Artists. Held at the Dominion Gallery from March 11 to April 5, the show introduced him to the art of the Professional Native Indian Artists Inc. (PNIAI). The exhibition included the work of Jackson Beardy (1944–1984), Eddy Cobiness (1933–1996), Alex Janvier (1935–2024), Norval Morrisseau (1931–2007), Daphne Odjig (1919–2016), Carl Ray (1943–1978), and Joseph Sanchez (b. 1948). Houle was intrigued.

Few mainstream art museums and private galleries organized exhibitions of Indigenous art in the 1970s. The PNIAI’s purpose was to gain recognition of its members as professional, contemporary artists. They challenged old constructs and stimulated a new way of thinking about contemporary First Nations peoples, their lives, and their art. Houle recounted, “Before seeing this exhibition, I was not aware of work by contemporary Indigenous artists and was struck by the power of their work. Norval Morrisseau was an inspiration and I wanted to meet him. The exhibition laid the foundation of a distinctive narrative style solidly based on Anishnabe stories.”

Early Career

In 1970 Houle submitted the painting Red Is Beautiful, 1970, to an exhibition of the Canadian Guild of Crafts in Montreal at Hotel Bonaventure. Dr. Ted J. Brasser, Plains ethnologist at the National Museum of Man in Hull (now the Canadian Museum of History), saw it there and proposed its purchase for the museum. Red Is Beautiful was the first of Houle’s works to enter a museum collection. After its acquisition, while pursuing his education, he had turned painting into a full-time occupation.

In 1977, with the intention of eventually moving to Toronto, Houle travelled from Montreal to Ottawa in search of a summer job. His friend Tom Hill (b. 1943) gave him the phone number of the executive director of the National Museum of Man, Barbara Tyler, and recommended that he call and apply for a position. Houle did, and was subsequently hired as the first Indigenous curator of contemporary Indian art. The commitment of an important national museum to create the job was significant—most institutions did not have such roles—and Houle was honoured to have been offered the position. The museum had an extensive collection of Indigenous art but previously had not had any staff with expertise in Indigenous knowledge and artmaking.

Houle’s curatorial work involved researching the museum’s existing collection, writing about Indigenous artists and their work, and curating exhibitions drawn from the collection. For the purposes of his research, he travelled across Canada to meet artists whose work, until then, he had seen only in books or on exhibition, developing close relationships with Abraham Anghik Ruben (b. 1951), Robert Davidson (b. 1946), Alex Janvier, Daphne Odjig, Carl Beam (1943–2005), and Bob Boyer (1948–2004), among others. At the museum, he championed the artists, proposing pieces for acquisition and writing about their work. On one of his trips Houle met Norval Morrisseau for the first time. Morrisseau became a major influence and close friend. Houle recalled:

When I was writing a paper on Morrisseau for the museum and arranged to meet him, I was initially terrified. His reputation as an artist preceded him. When we met, we spoke in Anishnabe Ojibwa and we had a ball. He was so warm and engaging and from then on we became close friends.

Because Houle met with these artists in person and had an acute understanding of Indigenous knowledge, his curatorial work surrounding their art was more specific than what had previously been accomplished at the museum.

In his own artistic practice, Houle was searching for a personal vision informed by modernist aesthetics and spiritual concepts. He dedicated Mondays at the museum to artistic research, studying the styles associated with De Stijl and Neo-Plasticism, and the work of Piet Mondrian, whose purist approach, theosophical focus, “paring down of excess cultural baggage,” and insistence on order appealed to Houle.

As part of his duties at the museum, Houle also met Jack Pollock (1930–1992), founder of The Pollock Gallery in Toronto. Pollock represented Morrisseau and Abraham Anghik Ruben, and he gave Houle his first solo exhibition at a commercial gallery in 1978.

New Career Directions

After three years at the National Museum of Man, Houle had grown tired of seeing contemporary Indigenous art placed in ethnographic collections and of witnessing the inappropriate treatment of ceremonial objects. In an interview, he later stated, “I realized that artistically and aesthetically I was in hostile territory. There was no place to exhibit the contemporary works I bought for the museum, and I just could not accept that, as a practising artist, what I made had to be relegated to the realm of anthropology.” At a crucial moment, he witnessed a visiting ethnochemist (conservator) opening and examining the contents of an object in the museum’s collection: a medicine bundle—a living, holy object. This intrusion was a reflection of the museum’s misperception of what should be treated as sacred. For Houle, his curatorial role had become a burden. One day in the summer of 1980, armed with a sketch pad and pencil, he drew ceremonial objects, such as a parfleche, warrior staffs, and shields, held in the display cases. That afternoon he handed in his resignation.

Houle relayed, “When I was standing in that gallery surrounded by all those objects, presented in a context that isolated them from life and reality, all I could think of was that I wanted to liberate them.” His resignation was a pronounced refusal to condone the museum’s spiritual transgressions against sacred objects and Indigenous knowledge. It made national headlines and would come to mark the year 1980 as a pivotal moment in the post-colonial history of North American visual art. “I had to start exhibiting in the U.S.,” Houle later said, “because somehow I’d gotten blacklisted—this young red boy holds a prestigious position and throws it back to the wolves. But I made the move from a survival instinct, not malice.” Houle determined that the best way to promote Indigenous art and representation was as an artist: to connect contemporary artistic expression with objects associated with shamanistic and ritualistic art.

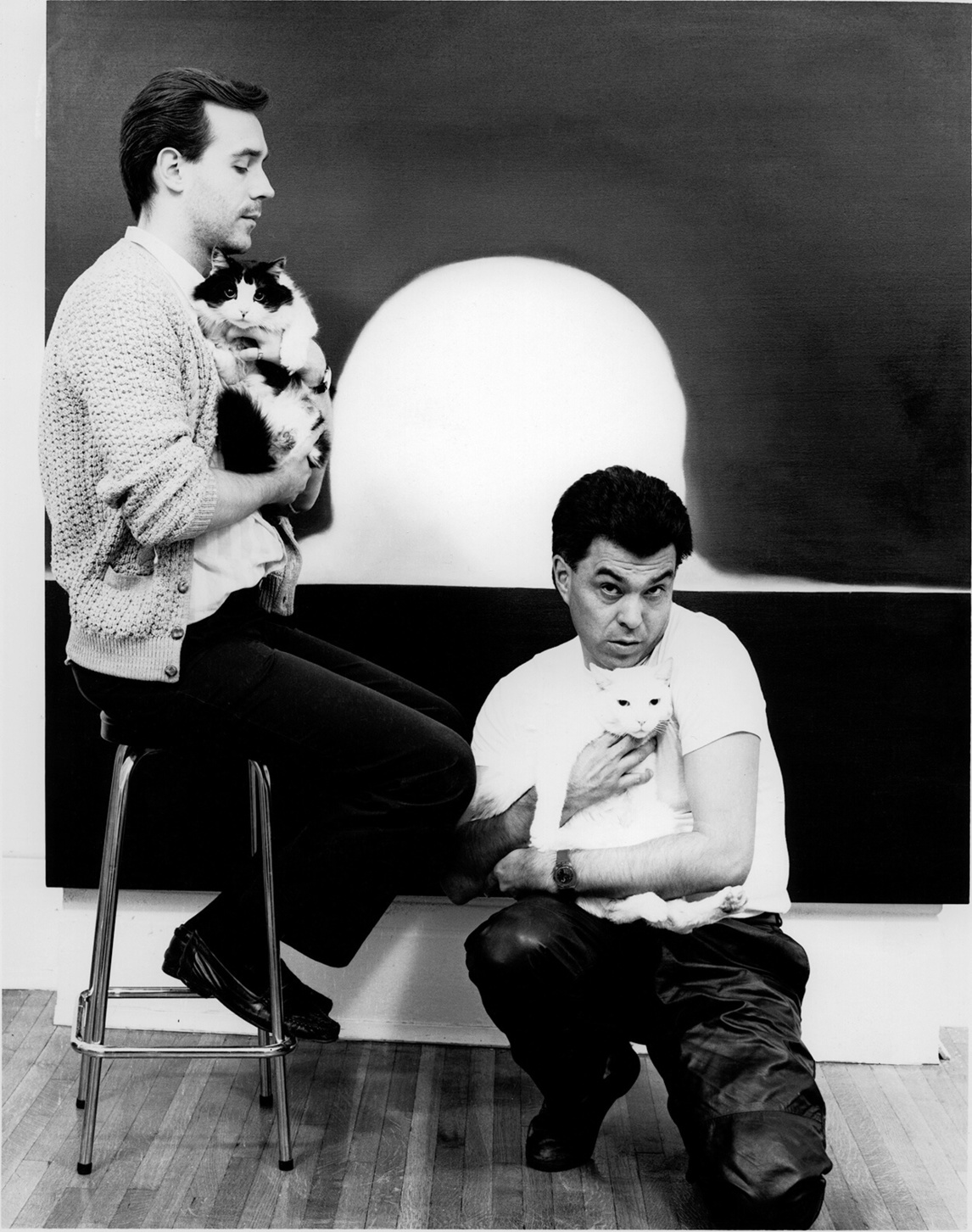

The day Houle quit the museum, he received his first call from the man who would later become his partner in life, Paul Gardner, who had met Houle one evening in Hull (now called Gatineau) a while before.

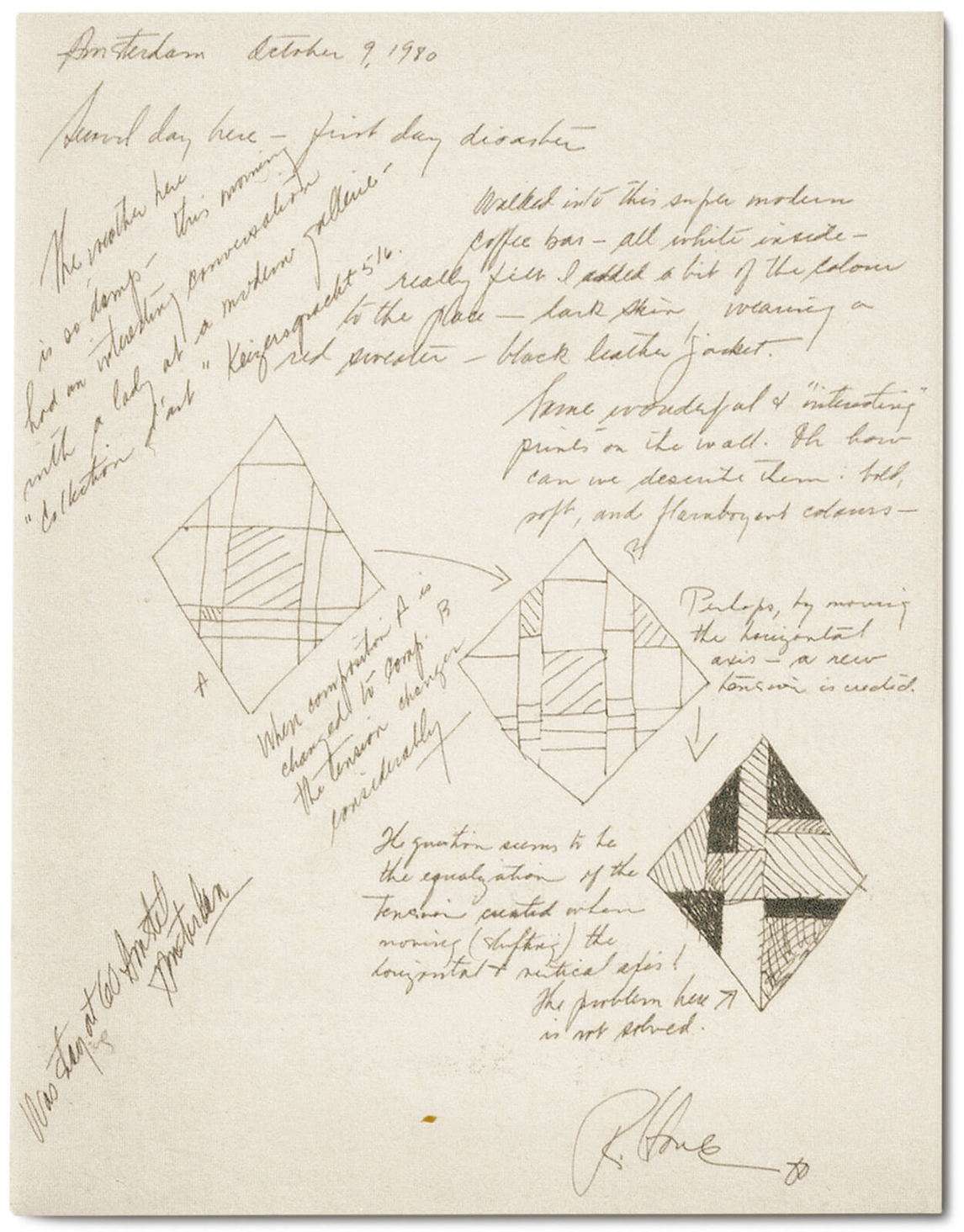

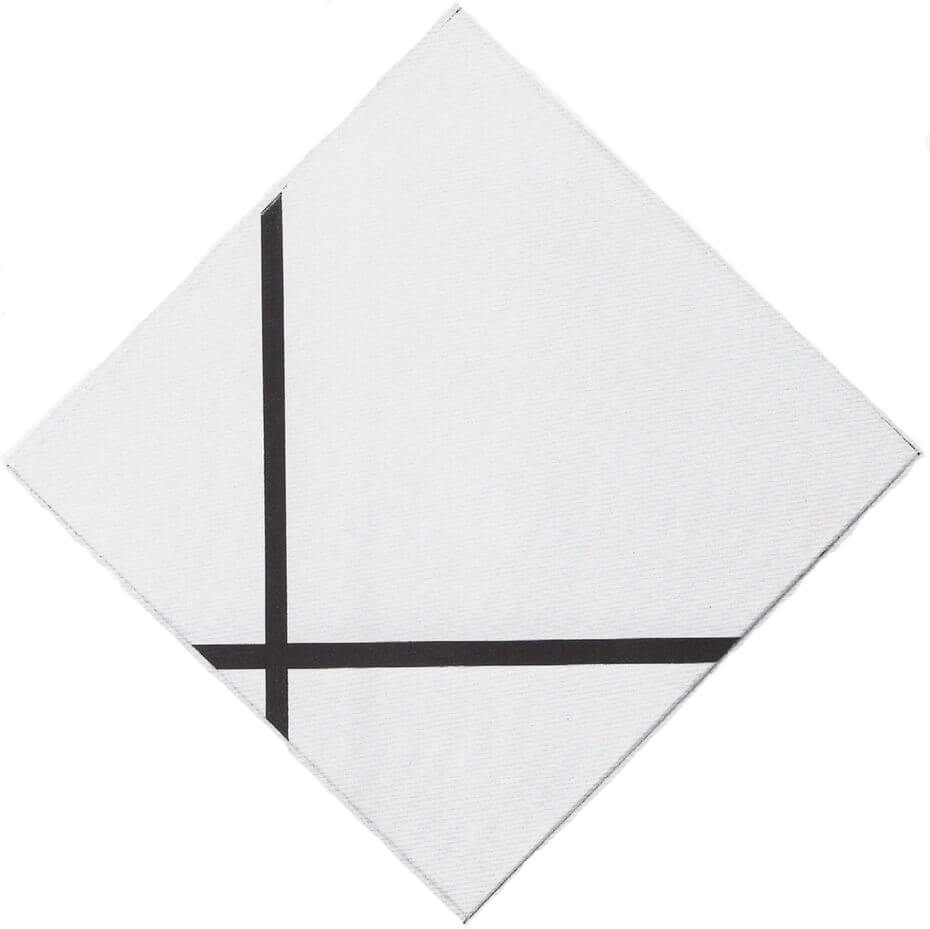

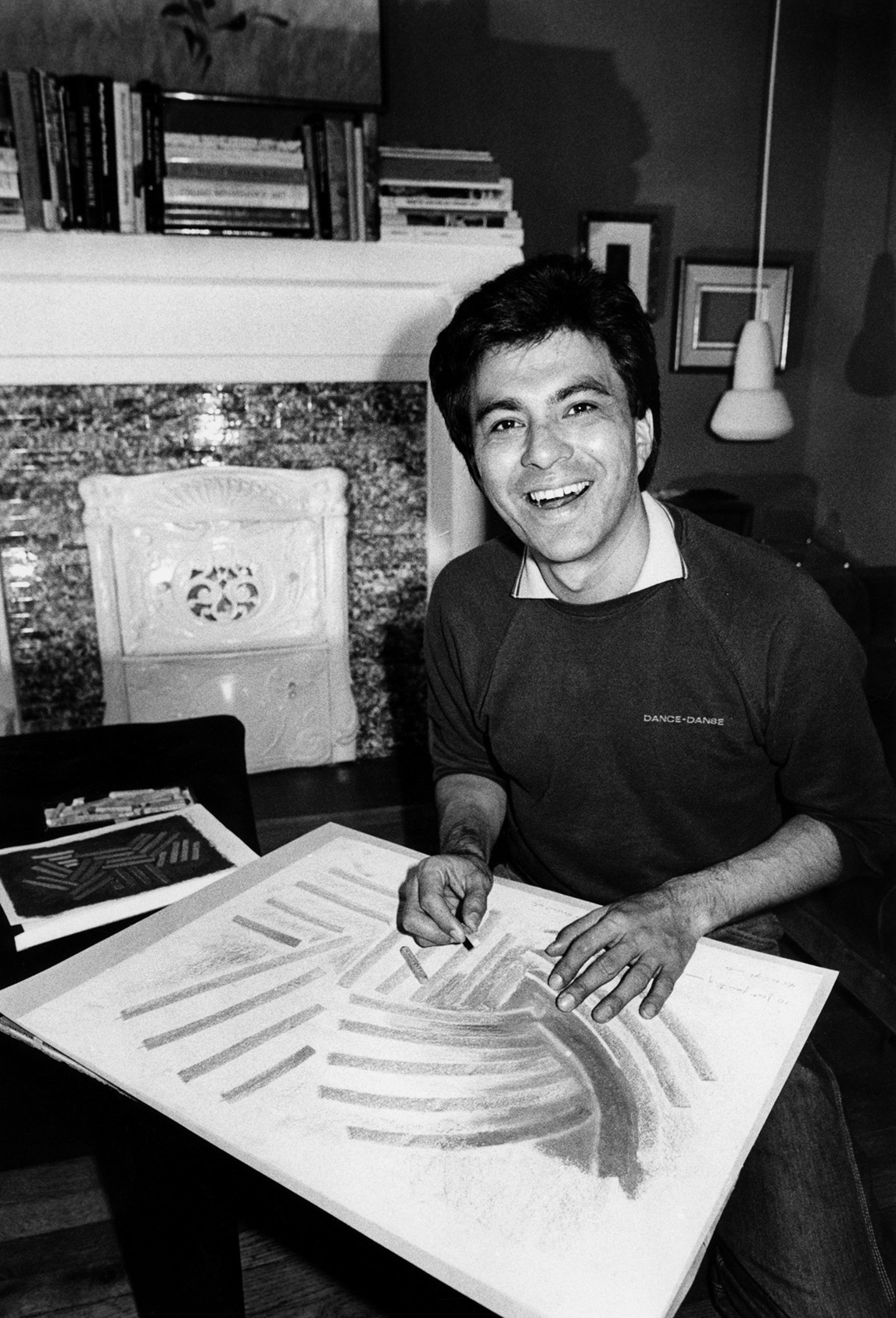

In September 1980 Houle travelled to The Hague and Amsterdam with a mission to study the work of Piet Mondrian first-hand. He was surprised to view Mondrian’s delicate small brushwork, which he perceived as giving humanity to the tension created by the Dutch painter’s shifting of horizontal and vertical axes, as in Lozenge Composition with Two Lines, 1931. In a drawing pad dated from 1980, Houle writes about how the gesture of the artist’s hand guiding the paint expresses the ineffable: “The application of paint, its own intuitive ability to make the unknown into a reality—the hand holding the brush must show as in Malevich, Mondrian and Vermeer.” But upon closer investigation, he found Mondrian’s approach too objective, lacking a natural palette and direct relationship with nature; too “man-centred” and not suited to Houle’s “holistic belief system” and connectedness with the earth.

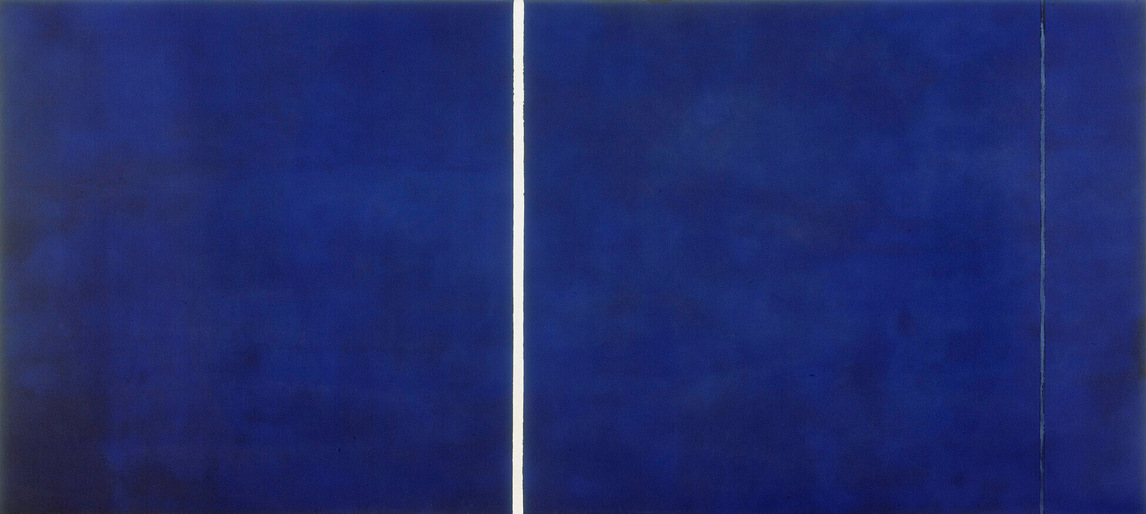

It was in Amsterdam that Houle’s attention turned to the American Abstract Expressionist painter Barnett Newman when, in the same gallery that held Mondrian’s works, he encountered Newman’s painting Cathedra, 1951, and his series consisting of eighteen colour lithographs (Cantos, 1963–64). “When I turned around in the gallery and saw Cathedra, I was completely taken aback and absorbed into the painting’s monumentality and the artist’s monochromatic approach, his direct method to convey spiritualism through abstraction and colour.”

Inspired by his visit overseas and eager to begin new work, Houle returned to Ottawa and in 1981 relocated to Toronto with Paul Gardner. Houle had found that the colour-field painting of Abstract Expressionism, with its exploration of gesture, line, shape, and colour to evoke strong emotional and spiritual reactions, was perfectly suited to communicating his own Indigenous spirituality. Colour-field influences would come to be seen throughout Houle’s oeuvre, in such works as Parfleches for the Last Supper, 1983; Muhnedobe uhyahyuk (Where the gods are present), 1989; Blue Thunder, 2012; and Morningstar II, 2014.

Curator of Groundbreaking Exhibitions

In 1981 Houle curated his first set of group exhibitions, Art Amerindian, which consisted of shows at the National Arts Centre, the National Library and Archives, and the Robertson Galleries in Ottawa, and the Municipal Art Gallery in Hull. The National Library and Archives exhibit included work by Gerald Tailfeathers (1925–1975) and Arthur Shilling (1941–1986). Other sites featured work by Alex Janvier, Benjamin Chee Chee (1944–1977), Jackson Beardy (1944–1984), Daphne Odjig, and Beau Dick (1955–2017), among others. The exhibitions explored realism, abstraction, and narrative in the work of First Nations artists and, along with well-known artists, introduced those whose work previously had not been profiled.

There were few appointments of Indigenous curators in Canadian art museums in the 1980s, and often Indigenous artists were called upon to advise and co-curate exhibitions with institutional curators. In 1982 Houle was invited to co-curate the exhibition New Work by a New Generation at the Norman MacKenzie Art Gallery (now the MacKenzie Art Gallery) in Regina with Bob Boyer and Carol Phillips, the gallery’s director. This was the first major exhibition of contemporary Indigenous art from Canada and the United States, and it helped establish relationships between artists from across Turtle Island (known in colonial terms as North America). Houle’s own work was exhibited alongside that of Boyer, Abraham Anghik Ruben, Carl Beam, Domingo Cisneros (b. 1942), Douglas Coffin (b. 1946), Phyllis Fife (b. 1948), Harry Fonseca (1946–2006), George C. Longfish (b. 1942), Leonard Paul (b. 1953), Edward Poitras (b. 1953), Jaune Quick-to-See Smith (b. 1940), and R. Lee White (b. 1951).

The exhibit was also the first in Canada to situate this emerging generation of contemporary Indigenous artists whose work is informed by their history, values, and culture. It showed a radical departure from previous conceptions of Indigenous art often associated with traditional practices, such as the Woodland School or Haida art. Boyer, for instance, produced political abstract paintings on blankets with geometric designs derived from the traditional motifs of Siouan and Cree groups in Western Canada. Beam worked with photography and collage in an aesthetic style akin to the expressive layering of American pop artist Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008) yet engaged with his Ojibwa traditions. Two of the four works of his own that Houle included were Punk Schtick, 1982, and Rainbow Woman, 1982.

Art That Reconstructed Histories

In 1983 Houle produced a work that marked a turning point in his oeuvre, Parfleches for the Last Supper, a series of thirteen paintings that combine two diametrically opposed ideologies: Christianity and his Saulteaux heritage. Here the Last Supper functions as a metaphor for the times his mother would call the naming shaman to come and give spirit names to her newborns. The ritual included a special meal, with the name-giver opening his medicine bag to reveal his rattle and sacred amulets and medicines. By traditional people in his community, Jesus at the Last Supper is understood to be a shaman with healing powers. The work represents Houle’s synthesis of the two epistemologies, or systems of knowledge, that most influenced his artistic formation.

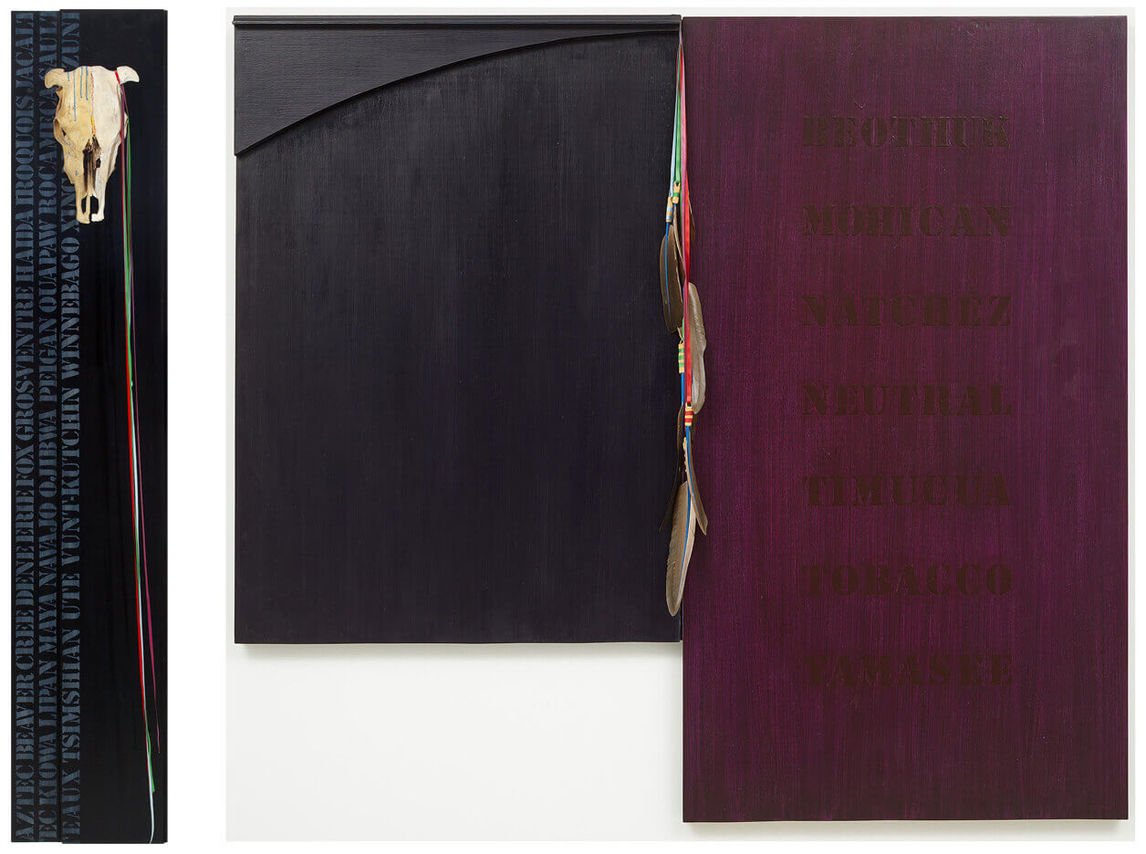

In Canada throughout the 1980s, curators and artists were still debating whether contemporary Indigenous art had a place in mainstream galleries or if it should be situated anthropologically in museums. In response, between 1983 and 1988, Houle inflected his artwork with a profoundly more political hue, focusing on reconstructed histories of Indigenous peoples, as in Everything You Wanted to Know about Indians from A to Z and The Only Good Indians I Ever Saw Were Dead, both from 1985. Houle documented the names of North American Indigenous nations, many of which had vanished as a result of colonization. Subsequent works—for example, In Memoriam, 1987; New Sentinel, 1987; and Lost Tribes, 1990–91—continued the discourse about representation and naming, and made the extinct visible again.

Two residencies in 1989 moved Houle to explore the subject of land with a fresh outlook. From February to April 1989, Houle was artist-in-residence at the Winnipeg Art Gallery. He noted:

I had turned to oils at that time, because two years before that my mother had died, somebody who had brought me into this world, and I wanted to make a demarcation in my career forever…. Up to that point I had been working almost exclusively in acrylic. I switched to oils.

The residency allowed Houle to immerse himself in new work connected to his heritage. The result was the completion of four monumental abstract paintings, Muhnedobe uhyahyuk, 1989. The work continued the spirituality of Parfleches for the Last Supper but with an emphasis on the prairie landscape, in particular a spiritual place of legend on the northern part of Lake Manitoba, known in Anishnabemowin as muhnedobe uhyahyuk, meaning “the place where the gods are present.”

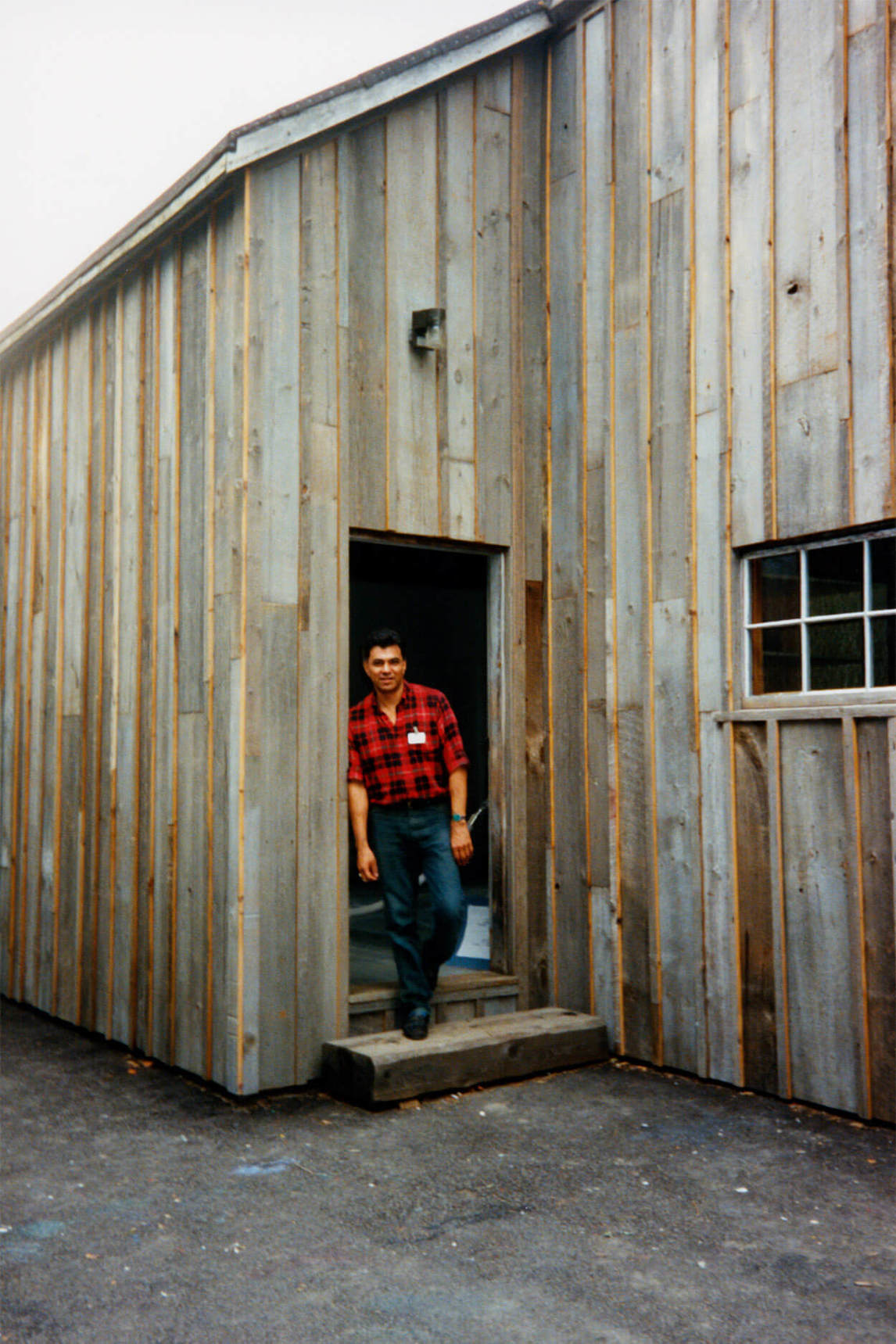

In the fall of 1989, Houle was artist-in-residence at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in Kleinberg, Ontario. By then he had well established himself as an abstract artist, but he realized that he had no visual vocabulary for landscape painting in the literal sense. Houle’s understanding of land differs from the typical Western perspective of ownership. Land is a shared source of being; the interconnectedness of humankind and nature, and the spirituality in the land, is fundamental to how earth-centred people view their relationship with Mother Earth. While at the McMichael Houle photographed the grounds and studied paintings by Tom Thomson (1877–1917) and the Group of Seven in the permanent collection. Thomson’s work, especially the tactile physicality of his paint and technique, intrigued Houle. But the ghosts of the Group and their nationalistic approach were challenging.

The outcome of the residency was a work that elucidates both an earth-centred relationship to land and the losses First Nations experienced as a result of contact with Europeans: Seven in Steel, 1989, an impressive installation consisting of seven highly polished steel slabs that incorporate small, semi-abstract painted vignettes of Indigenous art objects held in the McMichael Collection, including a totem pole fragment, Inuit hunting spears, and animal figures. Lined up side by side at ground level and held together by strategically placed narrow strips of colour—red, yellow, and blue—each component of the installation is designated in memory of seven extinct nations and corresponds to a work by the Group of Seven.

Houle’s first solo exhibition in a public art gallery was held at the Winnipeg Art Gallery in 1990, Robert Houle: Indians from A to Z. Group exhibitions had become an issue for Houle, as he resisted being segregated as solely an Indigenous artist, aspiring that his work be considered mainstream within contemporary Canadian art. Some Indigenous artists believed Houle’s position on the matter denounced Indigenous heritage in his work, which was not the case. Before 1986 many public institutions, including the National Gallery, had practised a form of “cultural apartheid”—a phrase used by Houle in an interview with Carole Corbeil in the Globe and Mail. He felt that with a solo exhibition, he was taken seriously as a contemporary Canadian artist.

Houle also accepted a position as a professor of Native Studies at the Ontario College of Art (now OCAD University), Toronto, in 1990, becoming the first person to teach Indigenous studies at Canada’s oldest institute for art education. He would instruct there for fifteen years, sharing his knowledge of history and Indigenous culture and mentoring a new generation of curators and artists, including Shelley Niro (b. 1954), Bonnie Devine (b. 1952), and Michael Belmore (b. 1971). Houle was one of just a handful of Indigenous art professors in Canada at the time of his appointment.

Responding as an Artist and Activist

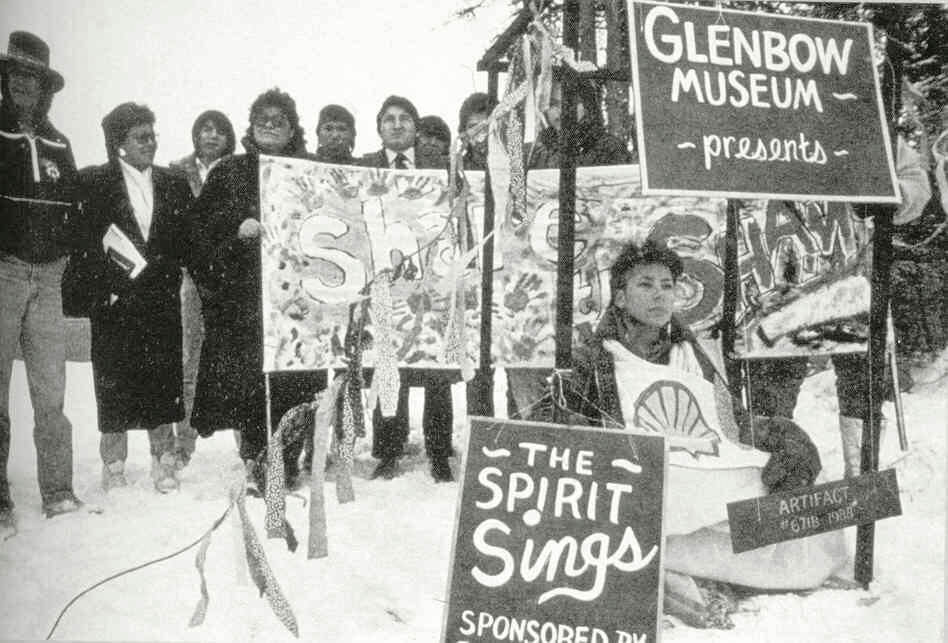

The 1980s and 1990s were a politically turbulent period affecting Indigenous communities across the country. One such instance was when, in conjunction with the 1988 Winter Olympics in Calgary, the Glenbow Museum organized The Spirit Sings: Artistic Traditions of Canada’s First Peoples, which included historical objects borrowed from national and international ethnographic collections. The Cree Lubicon Lake Nation in northern Alberta led a widely publicized campaign to boycott the exhibition. The Lubicon had been resisting oil exploration in their traditional territory, with oil companies raking in profits while the federal government would not grant the Lubicon a reserve. Meanwhile the federal government and the oil company Shell Canada were sponsors of the exhibit. The Lubicon asked for museums not to lend objects to the show and for people not to attend, but to little effect.

In sympathy with the Lubicon, Houle had no intention of viewing the exhibition. However, after learning that there were artifacts borrowed from private collections in Europe that he wanted to see, Houle purchased a yard of black ribbon, which he wore as an armband while attending the touring show at the National Gallery of Canada in the Lorne Building. He was totally repulsed by a display of a pair of tiny moccasins and an effigy from the grave of a four-year-old. “Viewing these looted Beothuk artifacts in the former bastion of European aesthetics—the National Gallery of Canada—the trivialization of a human tragedy was compounded by my knowledge that the sponsoring institution, the Canadian Museum of Civilization, was the depository of sacred and ceremonial regalia seized by the federal government.”

Subsequently, Houle produced Warrior Shield for the Lubicon, 1989, a work that transforms the lid of an oil drum into a shield showing an abstracted landscape. Ruth B. Phillips notes the work confronted contemporary political issues using “a complex language of styles, genres, and media,” through which the artist “announces himself the postmodern inheritor of multiple and distinct artistic traditions.”

In the summer of 1990 for seventy-eight days a small group from the Mohawk nation of Kanesatake stood off against the Quebec provincial police and the Canadian army in defence of a sacred burial ground from the impending encroachment of a golf course in the town of Oka, Quebec. The dispute was the first well-publicized violent conflict between First Nations and the Canadian government in the late twentieth century. Houle writes, “For the people of Kanehsatake and Kahnawake it was state terrorism, the act of war without a declaration of war, so that there is no formal protection of civil rights or internationally regulated political rights….”

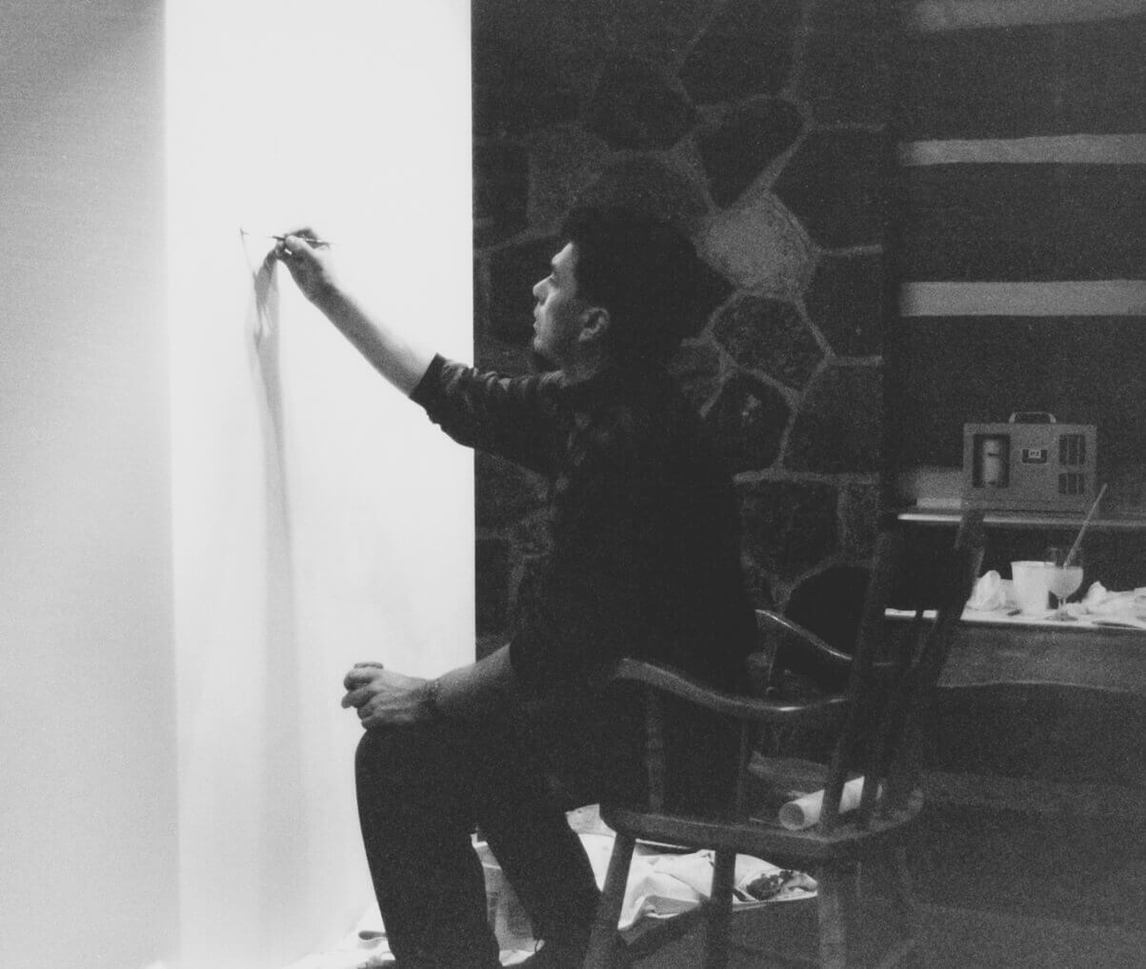

During this crisis, police and soldiers surrounded the same longhouse in Kahnawake where Houle had taught in 1972. He created a window installation in his Toronto apartment, Mohawk Summer, 1991, in support of the Mohawk. “When that longhouse was surrounded, it really hit me,” Houle said. “That’s why I blocked my Queen Street studio windows with banners, and literally deprived myself of light so I could not paint.” The historic crisis has reverberated through other works, including Kanehsatake, 1990–93, and Kanehsatake X, 2000. It was while the banners of Mohawk Summer hung in his windows that Houle was visited by curators Diana Nemiroff and Charlotte Townsend-Gault and began discussions that would lead to a crucial exhibition in the history of Indigenous and Canadian art.

Land, Spirit, Power: First Nations at the National Gallery of Canada

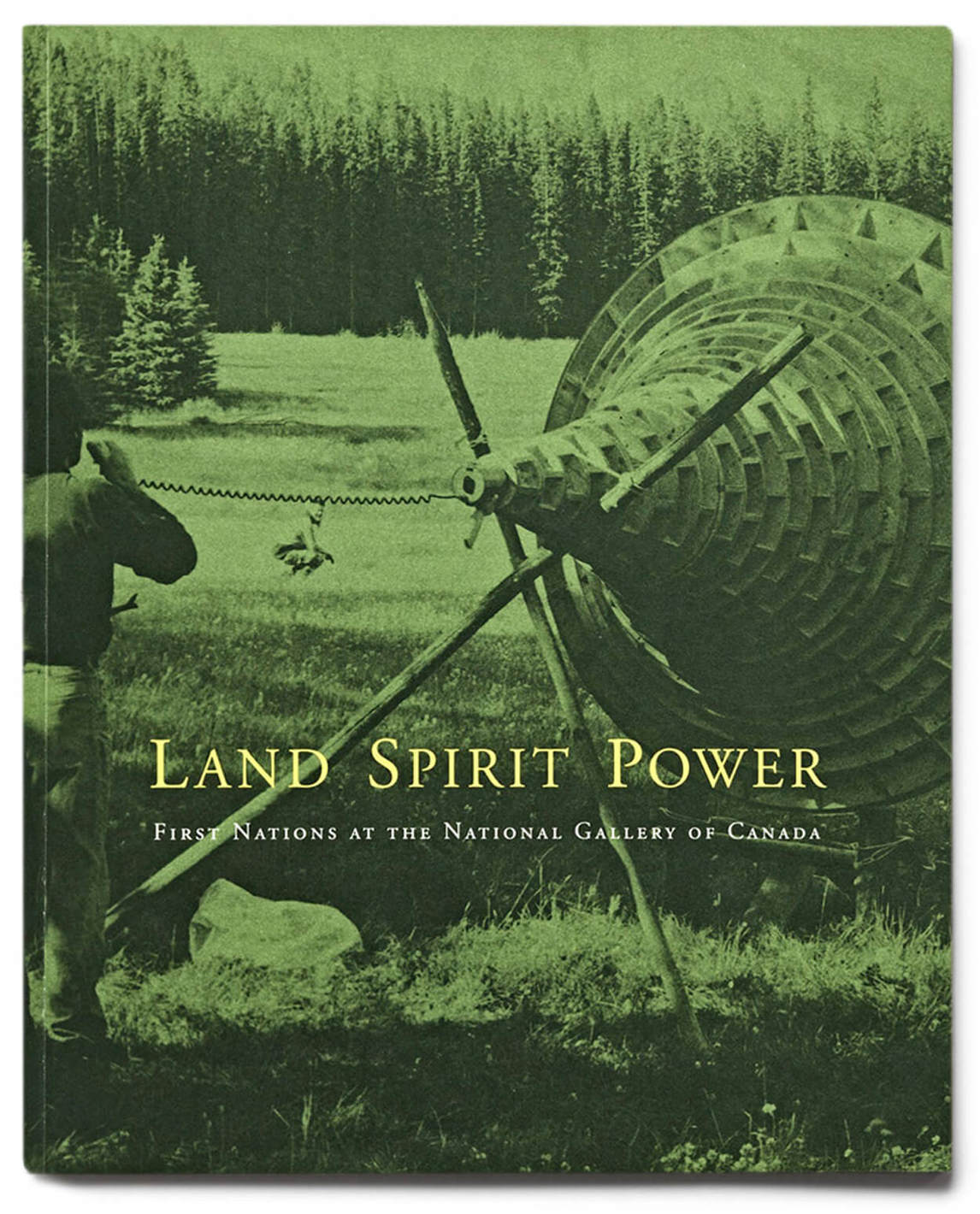

In 1992, at the invitation of Diana Nemiroff, curator of modern art at the National Gallery of Canada, Houle agreed to co-curate Land, Spirit, Power: First Nations at the National Gallery of Canada, with Nemiroff and Charlotte Townsend-Gault. Previous to this exhibit, Indigenous art had not yet been widely seen as contemporary, and generally it was still acquired and exhibited in historical contexts rather than in contemporary art galleries. Land, Spirit, Power brought an unprecedented level of mainstream recognition and prompted the integration of Indigenous art into contemporary art collections, impacting the permanent installations and the documentation of work by Indigenous artists in museums across the country.

While researching Land, Spirit, Power, Houle visited artists across North America, including Rebecca Belmore (b. 1960), Dempsey Bob (b. 1948), Jimmie Durham (b. 1940), Edgar Heap of Birds (b. 1954), Faye HeavyShield (b. 1953), Zacharias Kunuk (b. 1957), and Kay WalkingStick (b. 1935). In his influential essay for the show’s catalogue, Houle frames these contemporary artists within an art tradition that predates European settlement by thousands of years. He further attests that their knowledge acquired at Western art schools “(sometimes minefields netted with trenches of assimilation, discrimination, and oblivion), combines with their unique legacy to prepare them to create a new plastic language that has a spirit. A contemporary art, which is both new and indigenous …”

During Houle’s work on the exhibition, he encountered the painting The Death of General Wolfe, 1770, by Benjamin West (1738–1820), owned by the National Gallery and displayed alongside a selection of Indigenous objects—a pouch, and a garter and hatband as worn by one of the soldiers—on loan from the British Museum, London. While Indigenous artists were taking control of their own representation in Land, Spirit, Power, in another part of the gallery, heritage was being represented in a conventionally ethnographic way. Such irony was not lost on Houle. Seeing The Death of General Wolfe inspired his inquiry into the history of the French and English. His research resulted in the creation of Kanata, 1992, a controversial historical revisionism created during a tense period of constitutional deliberations in Canada, during which he felt First Nations were in “parenthesis.” In discussing Kanata, Houle articulated the place of Indigenous peoples in the history of Canada as one leg in “a tripod in Confederation, a land of French, British, and First Nations.”

Throughout the 1990s and into the 2000s, Houle continued to make art with a focus on First Nations and land issues, as seen in Premises for Self-Rule, 1994, a series of five lushly coloured paintings combined with photographs and texts from five treaties that confirm First Nations’ self-government and sovereignty over land in Canada. In 1999 the Winnipeg Art Gallery organized a second solo exhibition of work by Houle, Sovereignty over Subjectivity, marking another milestone in his career. The exhibition included three site-specific public artworks: These Apaches Are Not Helicopters, Morningstar, and Gambling Sticks, all from 1999, that combined with the works on display at the gallery posed many questions about political and cultural issues in the history of Canada, including land claims, self-government, residential schools, and nomenclature. Works such as Coming Home, 1995; Aboriginal Title, 1989–90; and I Stand …, 1999, were included in the exhibition.

Into the Twenty-First Century

Throughout the first two decades of the twenty-first century, Houle has received much recognition for his contributions to Canadian visual culture and for his stature as a pre-eminent artist, educator, curator, and critic. He became a member of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts in 2000, received the Toronto Arts Award for Visual Arts in 2001, and was awarded the Distinguished Alumnus Award by the University of Manitoba in 2004. Houle has received two honorary doctorates and, in 2015, the prestigious Governor General’s Award in Visual and Media Arts.

Houle resigned from the Ontario College of Art and Design (now OCAD University) in 2005 after receiving a major grant from the Canada Council for the Arts, which included participation in the Canada Council International Residency Program at the Cité internationale des arts in Paris, in 2006. This residency resulted in an iconic work, Paris/Ojibwa, 2010, which continued Houle’s research into the nineteenth-century Romanticist painter Eugène Delacroix begun during his university days in Montreal.

In 2009 Houle created the Sandy Bay Residential School Series, a highly personal artwork that reclaims his memories of the residential school experience. Two years later the Canadian government’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) began taking testimony from an estimated eighty thousand residential school survivors across Canada. To the TRC, reconciliation is about establishing and maintaining a mutually respectful relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples in the country. For that to happen, there has to be awareness of the past, acknowledgement of the harm that has been inflicted, atonement for the causes, and action to change behaviour. Houle chose not to participate in the TRC largely because of the prominence of the concept of “reconciliation” as a form of forgiveness. More meaningful to Houle is pahgedenaun, an Anishnabe term that translates roughly as “let it go from your mind.”

At a solo show at Toronto’s Kinsman Robinson Galleries in 2016, Robert Houle: Shaman Dream in Colour, Houle exhibited works created between 1998 and 2015, including abstractions of intense colour, such as Shaman, 2011; Blue Thunder, 2012; and Morningstar I, 2014. More recent figurative renderings in monochromatic shades of black, white, and grey, such as Shaman Takes Away the Pain, 2015, and Shaman Never Die, 2015, honour the influence of shamans on his life and work. In June 2017 Houle completed a triptych, O-ween du muh waun (We Were Told), which continues the polemics that began with Kanata, 1992, with the same Delaware warrior featured as the central figure. Whereas some of this recent work is rendered in richly evocative and subtle monochromatic shadings, others are abstractions in vibrant colours.

The year 2017 witnessed significant moves in art museums and public art galleries across Canada, as well as in funding agencies such as the Canada Council for the Arts, to focus on the work of Indigenous artists and curators through special programs and grants. The confluence aligned with subjects Houle had been discussing for forty years. As an artist, curator, and educator, he has been working for the recognition of Indigenous art and artists in North America; to raise awareness of issues surrounding land claims, water, and Indigenous rights; to decolonize museums; and to assert Indigenous peoples’ rights to their own representation. He has disrupted outdated methods of exhibiting Indigenous art and created paths for future curators of Indigenous art, such as Greg Hill (b. 1967), Gerald McMaster (b. 1953), and Wanda Nanibush (b. 1976). His work has inspired two generations of Indigenous artists to move bravely beyond traditional methods, embrace mainstream contemporary discourse, and proactively challenge colonial narratives of art history.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements