Within the history of Inuit art, Pitseolak’s dedication to the development of her personal style and technique through thousands of drawings is remarkable. Beginning with sewn and embroidered work, she progressed quickly to drawing, first with graphite and later experimenting with coloured pencils and felt-tip pens. Many of her drawings were made into prints, and she also tried her hand at printmaking. Pitseolak approached each new medium in a disciplined manner, with an openness to experimentation and a determination to excel.

A Self-Taught Artist

During the course of her career Pitseolak made over 8,000 drawings—by some accounts closer to 9,000, when those that were sold individually are included with those held by the Cape Dorset Drawing Archive.1 Pitseolak worked out on her own how to represent people, animals, objects, and especially the landscape, one step at a time through multiple drawings, many unfinished yet each progressively closer to achieving the effect she wanted to convey. Terrence Ryan (1933–2017), who ran the Kinngait Studios for decades, noted that during her most intense period in the 1970s, “Pitseolak, a woman of some seventy-one years, remains the most prolific, drawing almost daily.”2 Since almost every drawing bought by the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative for the print studio has been archived, Pitseolak’s body of work is available for study and offers an exceptional opportunity to gain insight into her creative process.

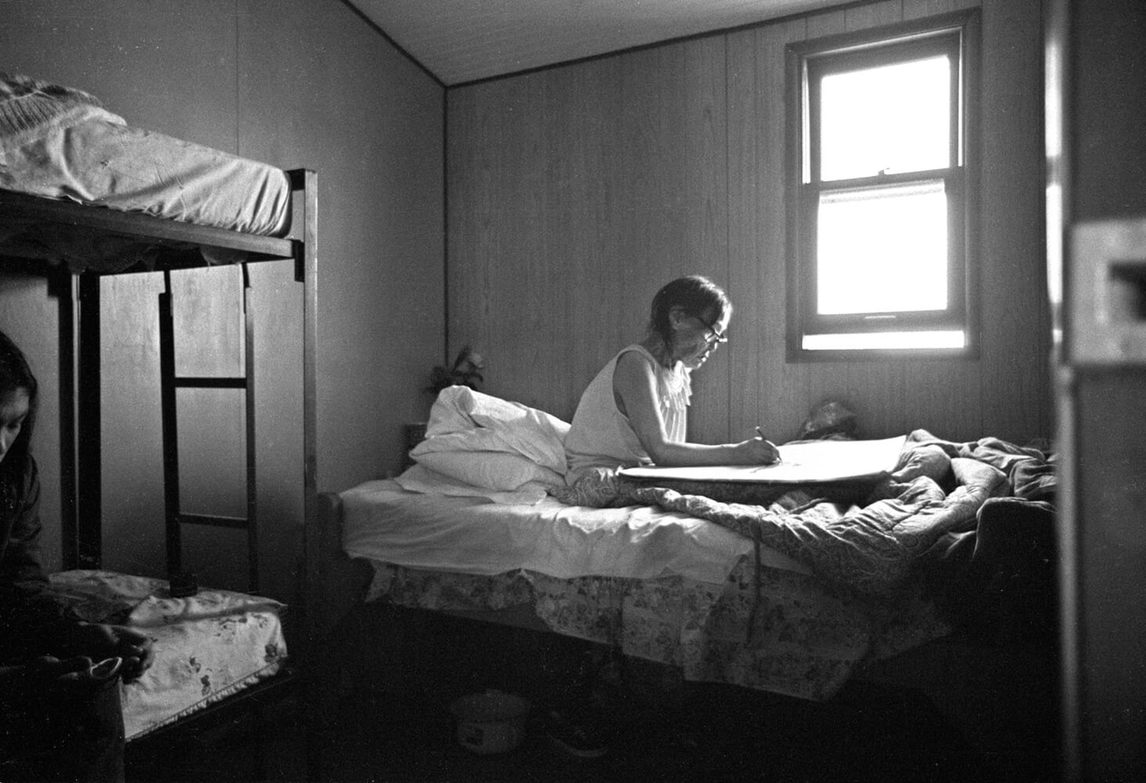

For most of her years in Cape Dorset, Pitseolak lived in her son Kumwartok’s household and like other Inuit artists created her drawings at home, in the midst of a large extended family. Many relatives, including her grandchildren, remember her sitting on her bed, legs stretched out or bent under her, drawing on large sheets of paper with a selection of coloured pencils and felt-tip pens. Her daughter, Napachie Pootoogook (1938–2002), recalled, “She used her own imagination and didn’t like intrusion when she was doing her work because she didn’t want her train of thought to be disturbed.”3 Yet Pitseolak seemed to welcome quiet visits from her grandchildren, such as Annie Pootoogook (1969–2016), who recalls standing by her bedside as Pitseolak created images.

Only after completing her drawings would Pitseolak take them to the studios. Patricia Ryan, who lived in Cape Dorset with her husband, Terry, described how “almost daily, Pitseolak carries a neatly wrapped package of her drawings to the co-operative.… She prefers to walk the distance of nearly a mile from the home she shares with her son and family.… At the co-operative she replenishes her supply of paper and frequently lingers to admire the drawings of fellow artists.”4 Pitseolak took these opportunities to see other artists’ imagery at the studio, but otherwise she worked alone at home, puzzling out artistic problems to her satisfaction as she strove equally for naturalism and expressiveness in her art.

From Sewing to Drawing

For the first half of her life Pitseolak used her sewing skills to provide her family with essential clothing, footwear, and shelter. After she and her family settled in Cape Dorset, she looked for ways to support herself and her multigenerational household. She saw an opportunity with the arts and crafts program introduced in 1956 by James Houston (1921–2005) and his wife, Alma Houston (1926–1997). Initiated by the Department of Northern Affairs and National Resources, the program was designed as an economic incentive for Inuit who recently settled in the community. James Houston introduced printmaking into the community, establishing a graphic arts workshop, and Alma worked with the local women to create marketable hand-sewn products. Pitseolak joined these women in the production of coats, hats, and mittens in wool and duffel, decorated in appliqué or embroidery and sold through the Industrial division of the Department of Northern Affairs and National Resources.

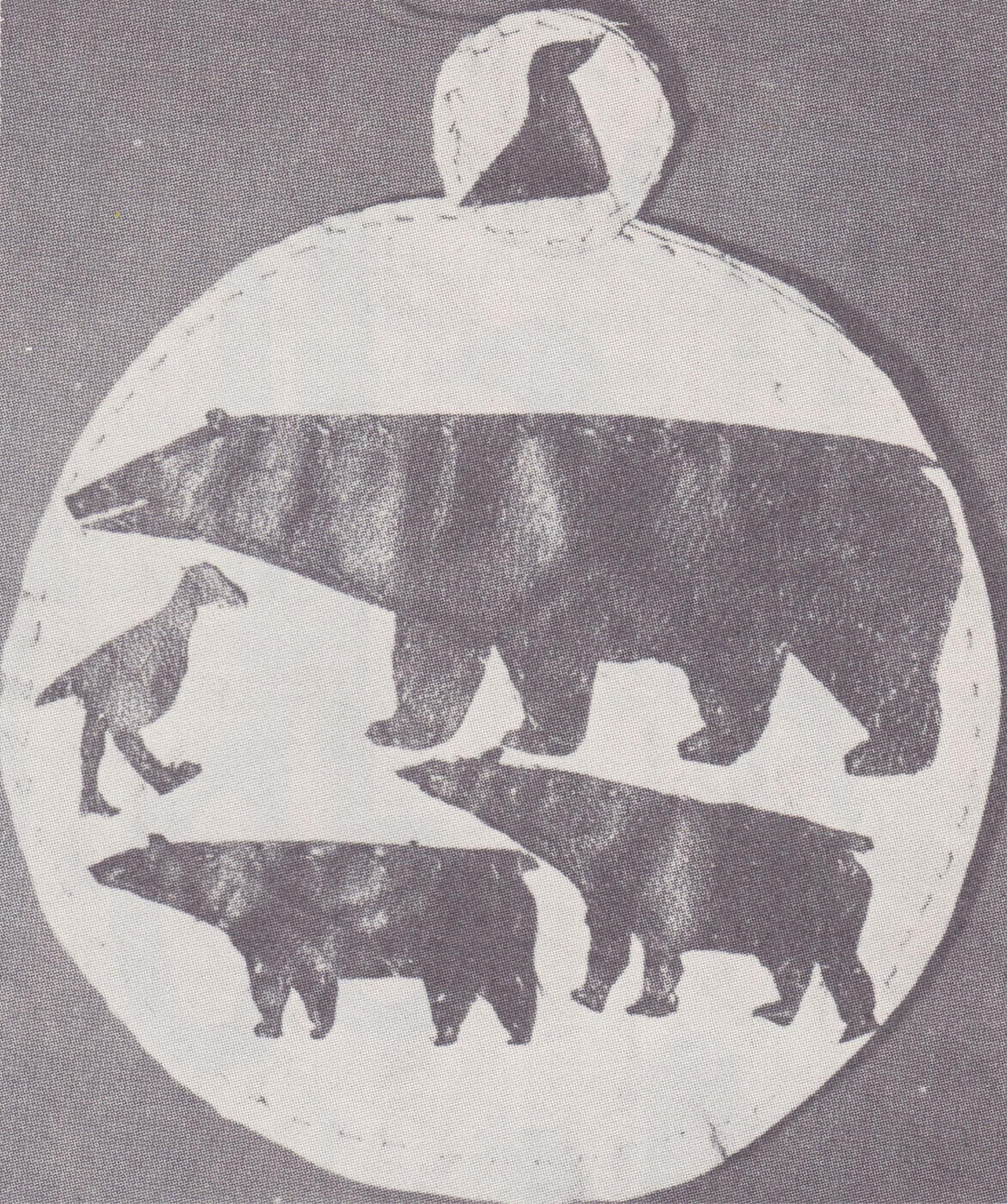

Although the sewing projects are not well documented, three examples give some insight into Pitseolak’s production. The 1964 promotional booklet Canadian Eskimo Art features an appliqué made of dark and light sealskin that pictures a bear hunt, complete with quirky walking birds, and is identified as “by Pitsulak (Woman) Tikkeerak Baffin Island.”5 Citing examples such as this, James Houston claimed that the appliqué and sewn imagery created by women provided a foundation for the use of the stencil process in the early days of the print studio.

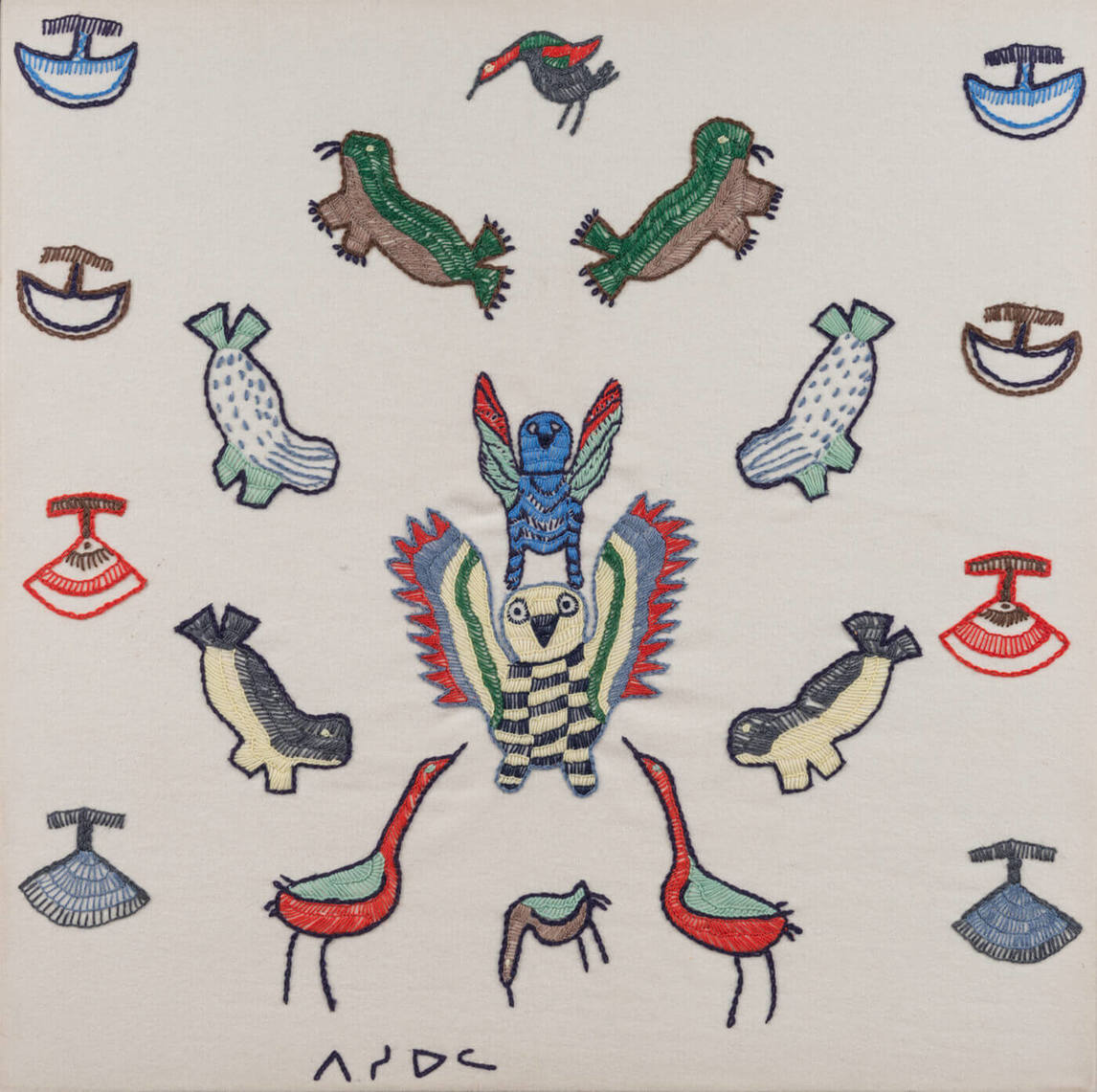

A coat made by Pitseolak for Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau with embroidered figures across the border is more typical of the kind of work she did a decade earlier with Alma Houston. A rare embroidered pictorial work on cloth from the 1960s—created by Pitseolak and presented to George Edwin Bell Blackstock, the Canadian Consul in New Orleans, by Alma Houston during a visit to promote Inuit art—is more closely tied to her drawings on paper.6

Pitseolak spent two years sewing goods for sale before she recognized another opportunity. By 1959 the Cape Dorset graphics studio was established, and it released its first catalogued print collection. On seeing the work of her cousin Kiakshuk (1886–1966), Pitseolak decided to try drawing, and she purchased paper and drawing materials.7 Her first efforts were well received by James Houston and later by Terrence Ryan (1933–2017), who succeeded Houston. She quickly became one of the most popular artists creating images for the annual Cape Dorset print collection.

From Graphite to Felt-Tip Pens

Pitseolak did not date her works, but many can be placed by the type of drawing instruments used.8 Initially, from the late 1950s until 1965, only graphite was available to the Cape Dorset artists. In 1966 coloured pencils were introduced, and the following year felt-tip pens became popular. Felt-tip pens, occasionally in combination with coloured pencils, remained popular until 1975, when the pens were phased out because of the impermanence of their colour.

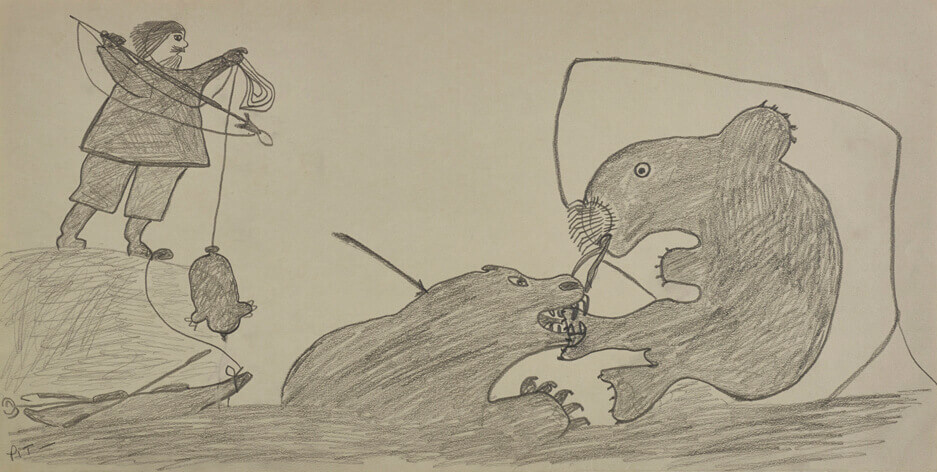

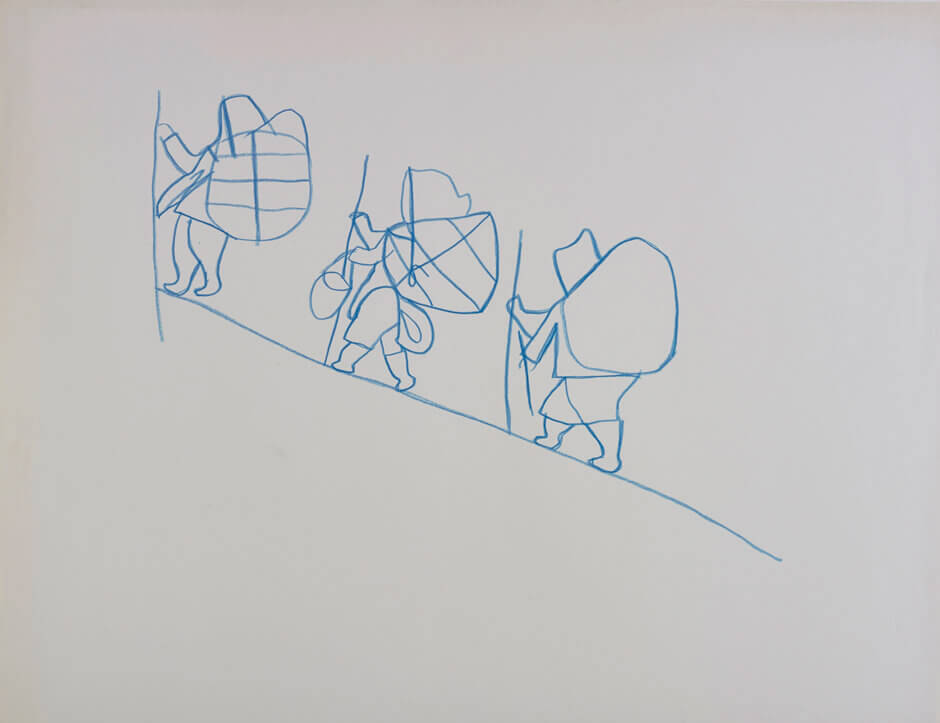

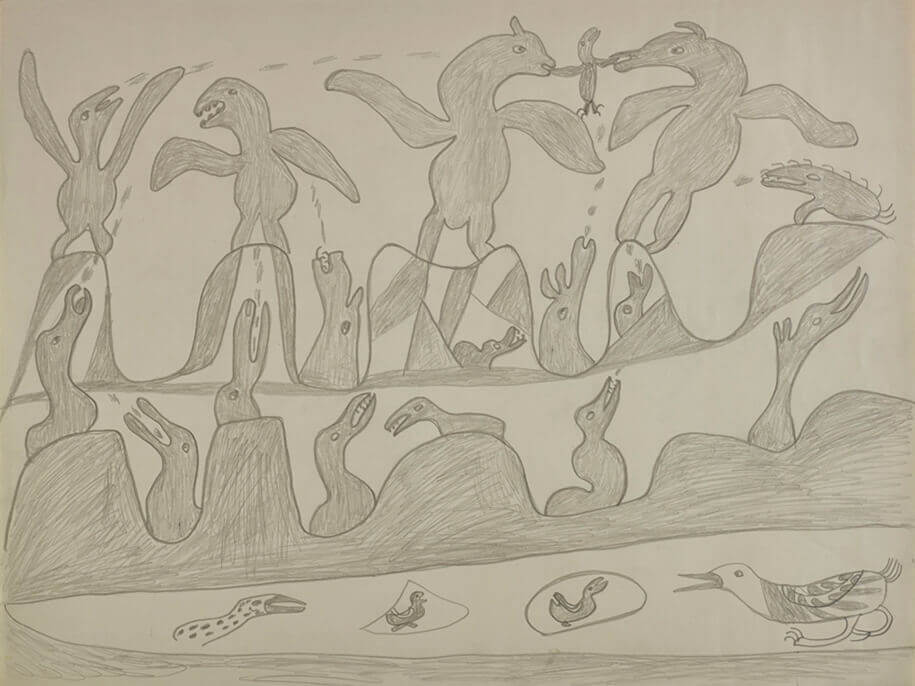

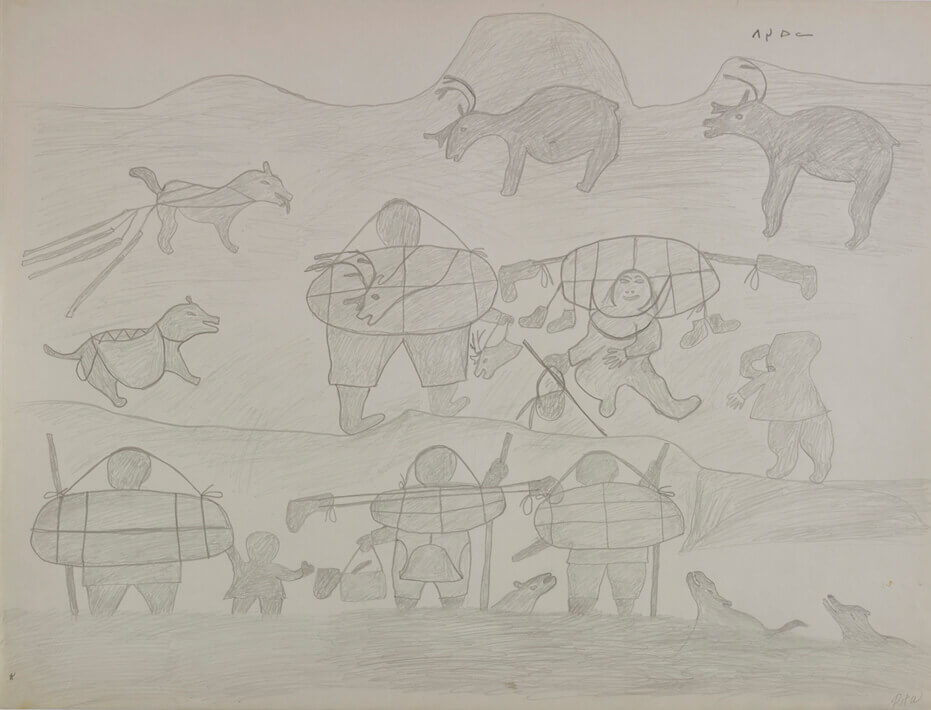

With only graphite available until 1965, Pitseolak had years in which to master her draftsmanship before moving into colour. In the earliest drawings, such as Untitled, c. 1962, she created an outline that she roughly filled in. This initial emphasis on line eventually became her strongest element. She learned to work in positive and negative space, both for compositional structure and for texture, to create variety and visual interest. By 1965 many of Pitseolak’s drawings demonstrate a confidence with various drawing techniques.

The transition from graphite to coloured pencils, and learning how these translated onto paper, was a fresh challenge for Pitseolak. In her earliest colour drawings, such as Untitled, c. 1965, Pitseolak experiments with the new medium, with somewhat erratic results. She adopts her previous method of outline and filler, while using all colours simultaneously.

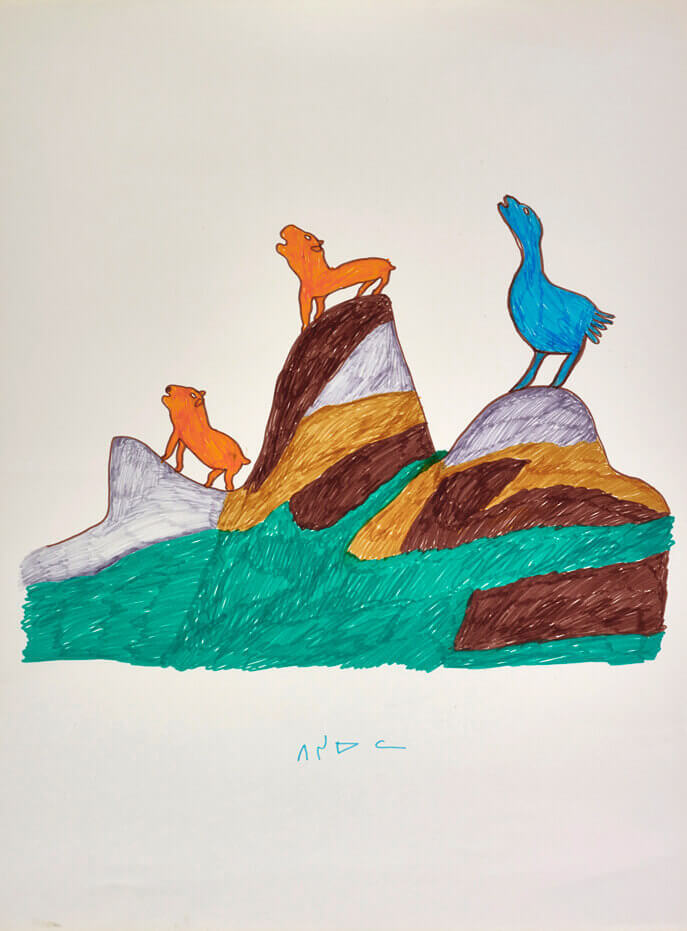

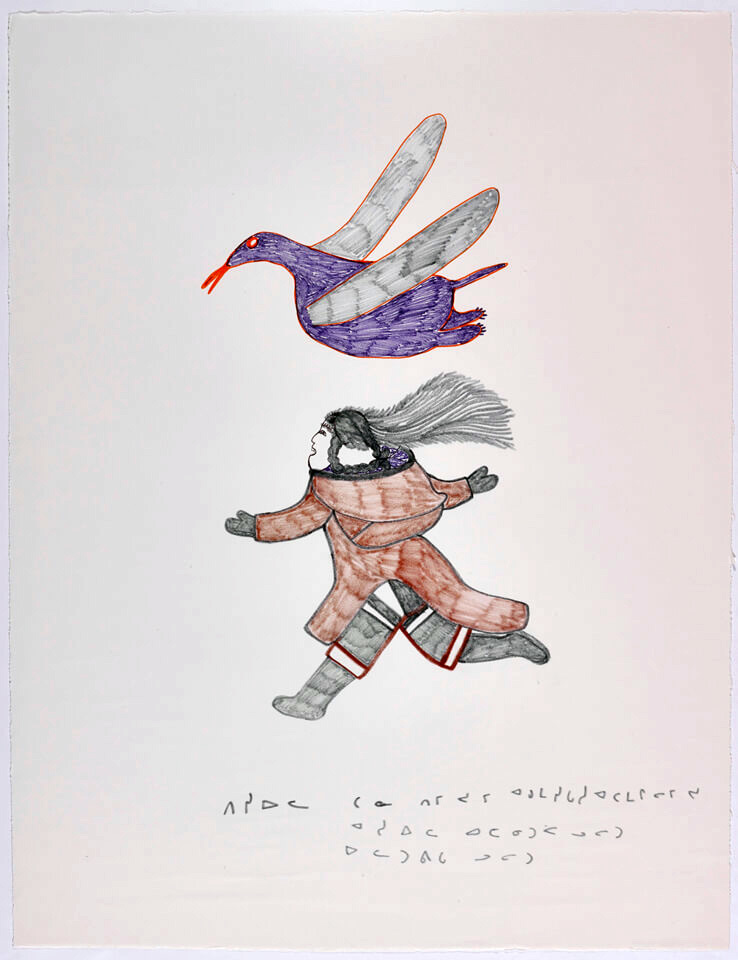

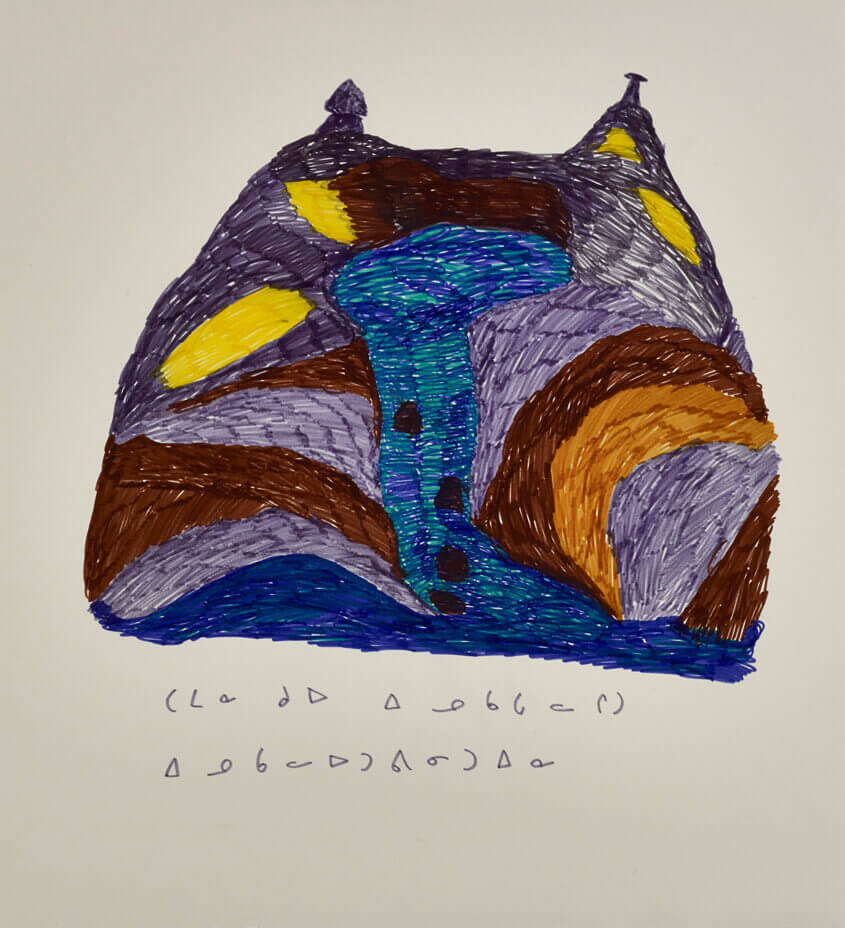

Felt-tip pens were Pitseolak’s ideal drawing medium. With their rich and vibrant colour, they best expressed the joyfulness that characterizes her work. By this time she had learned to control the combination of colour. She understood that a reduced palette, as in Untitled, c. 1966–67, can be stronger than a disarray of many colours. When it was discovered that the pens’ colour faded over time, the historian and writer Dorothy Harley Eber remembers how reluctant Pitseolak was to give them up.9 The switch back to coloured pencils may have frustrated Pitseolak, but she adapted, and the muted colours suit the subdued quality of her later drawings, such as Untitled (Solitary Figure on the Landscape), c. 1980.

Printmaking

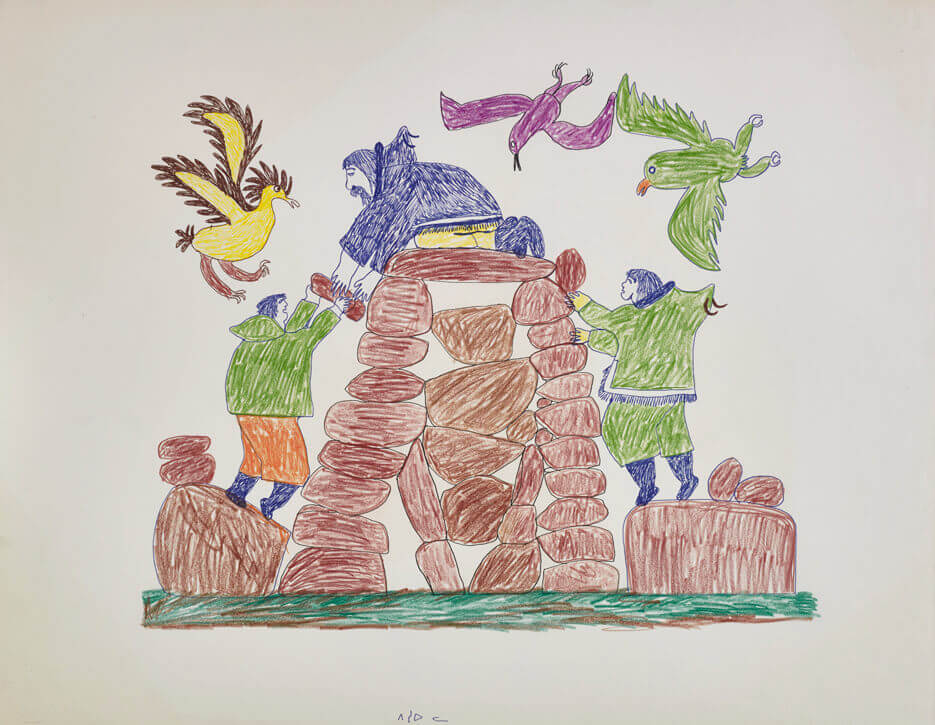

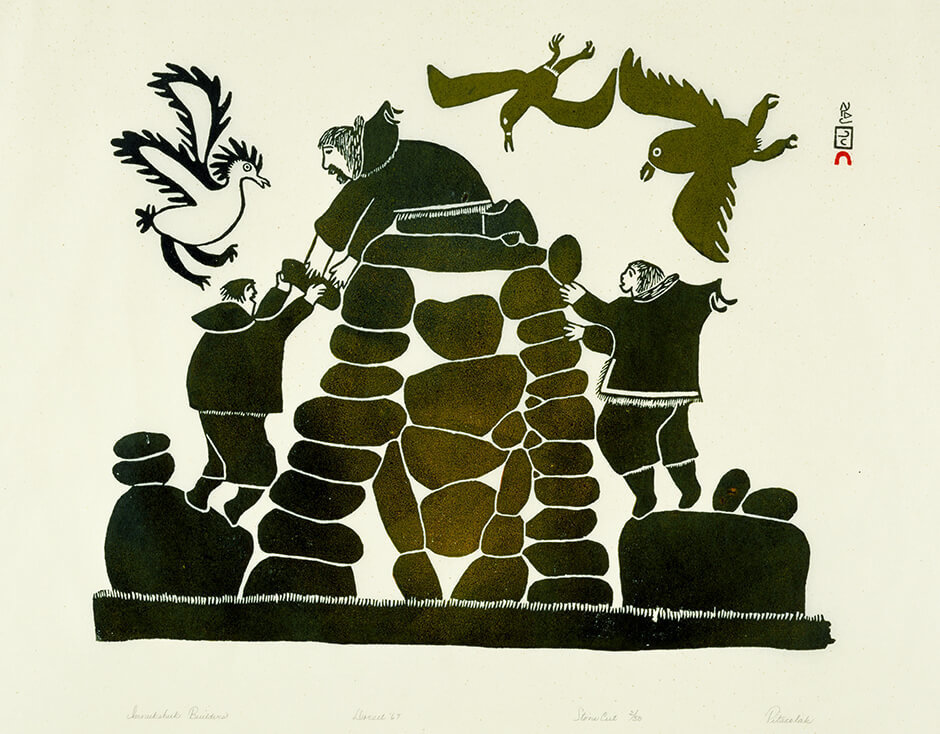

As can be seen in a comparison of the drawing and the print for Innukshuk Builders, 1968, a print tends to strengthen a graphic image; however, without the gestural strokes of the pencil, the energy of Pitseolak’s drawing style is largely absent in the print. This translation to print was evident in some artists’ work and was recognized early on by the print studio; it led to experiments in print techniques—such as engraving, etching, and lithography—that allowed the artist’s hand to be seen. Pitseolak was not active as a printmaker, but her drawing process did extend to working directly on copper plates and, to a lesser degree, lithographic stones.

She was one of the first artists to work on an engraving plate when Terrence Ryan (1933–2017) introduced them at the Cape Dorset studios in 1961. Her ability to create interesting scenes in line alone was well suited to engraving, but she found the materials difficult to work with: “I didn’t want to keep doing copper because I used to get very tired afterwards.… And I was very afraid of the tool. That very sharp tool used for scratching the copper is like a needle. The tool used to slip and one time I got cut on the finger. It went right through. When I worked on copper I was always expecting to cut myself,”10 she recounted.

Working on the etching plate, which consisted of drawing with a needle into a soft ground, allowed Pitseolak more ease and flexibility. Engraving and etching were discontinued in 1976 but revived by the studio in 1979. The following year two portfolios of etchings were released, including one devoted solely to her work, entitled Pitseolak: Childhood Memories.

Pitseolak participated in some of the experiments in lithography, a printmaking method that was introduced to Inuit artists by the American printmaker Lowell Jones (1935–2004).11 In an unpublished letter from 1972, the B.C. printmaker Wil Hudson (1929–2014) describes the studio:

In one corner of the shop, opposite from the press, old Pitseolak, a lady of about seventy-some years, croons to herself while she draws on the lithographic stone; she buries her head in her arms; presses a withered cheek against the stone, remains inert for minutes at a time. “Thinking,” she says, “is hard as housework. It is hard, hard.” She at length raises her head and resumes drawing12.

After three years of experimenting, the first lithographs were released in the 1975 Cape Dorset annual print collection, including Pitseolak’s First Bird of Spring, 1975.

Creating Movement and Space

Pitseolak experimented with her media and with the formal qualities of line, colour, and pictorial space until she mastered these and developed a personal style. This experimentation was motivated by a desire to accurately and expressively depict her favourite subjects. In particular she wanted to convey the movement of all things—people, animals, birds—as well as the familiar environment of her homeland.

Line is the most direct and expressive of the visual elements, and Pitseolak’s skill in this regard was undoubtedly her strongest talent. She described her drawing technique: “I draw the whole thing first and then I colour it. I do the whole drawing before I finish it.”13 Only after setting down the fundamental structure with line does Pitseolak build up her image with colour. This explains the predominance of line and also accounts for its spontaneous quality and almost nervous energy.

Pitseolak taught herself to draw figures, both human and animal. Series of her drawings made during the 1960s show how she learned to capture accurate proportions and movement so that her figures appear naturalistic. Even in her later drawings she makes no attempt at modelling or shading—techniques used to create the illusion of three-dimensional form—and yet her figures appear to have bulk and substance. After developing the ability to draw the figure, Pitseolak focused on how to depict the figure in motion, as in Untitled, c. 1965. Her fascination with depicting movement across the landscape can be related to her own nomadic lifestyle until the late 1950s.

Drawing on her memories of living on the land, Pitseolak made many images of the landscape, continuously refining her depiction of visual space. From her years of designing and sewing textiles, she adapted two devices found in Inuit clothing design—mirroring a motif, and breaking down the visual surface into registers. These devices proved especially useful in developing clear spatial divisions with different narratives and activities occurring in each of them. Her adoption of ground lines gave her landscapes foregrounds, middle grounds, and backgrounds. She associated space with distance and was able to convey the movement of figures through the land, as shown in Summer Camp Scene, c. 1974.

Pitseolak’s drawings of the land are an expression of her emotional ties and experiences. In later drawings, such as Untitled (Solitary Figure on the Landscape), c. 1980, figures become progressively smaller and are folded within the landscape. This can be seen as a refinement in her style but also suggests nostalgia for an immediate relation to the land. These later works may be Pitseolak’s way of revisiting the places of her younger years as well as an expression of regret for the passing of the nomadic way of life.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements