Pitseolak Ashoona’s body of work, its range and depth, was achieved through two decades of diligent effort and considerable creative energy. One of the first Inuit to create images of traditional life, Pitseolak contributed to the establishment of a modern Inuit art form that has received worldwide popular and commercial success. At the same time, her artworks play a vital role in the transmission of Inuit traditional knowledge and values. Beyond her own accomplishments, she has influenced generations of Inuit artists, leaving an important and lasting legacy.

Inuit Art Pioneer

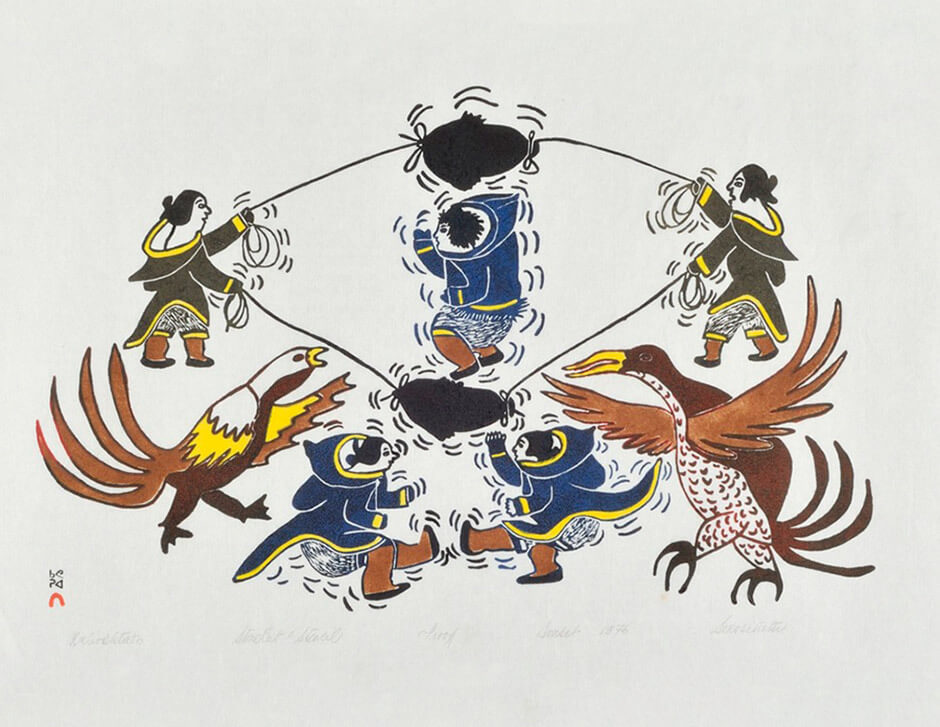

Pitseolak Ashoona was part of the first generation to make modern Inuit art—the most recent stage in the distinct aesthetic expression of the Inuit people, which can be traced back for millennia in Arctic Canada to the Sivullirmiut (first peoples) and Thule (ancestors of Inuit). In the mid-twentieth century, the art forms of sculpture, drawings and prints, and works on cloth were introduced to Inuit as economic initiatives, with the support of various governmental agencies. The art forms were as unprecedented as the tangle of complex circumstances evolving during this period of accelerated change caused by government intervention in the North. The critical and commercial success of contemporary Inuit art rests on the foundation built during this time by artists of Pitseolak’s generation.

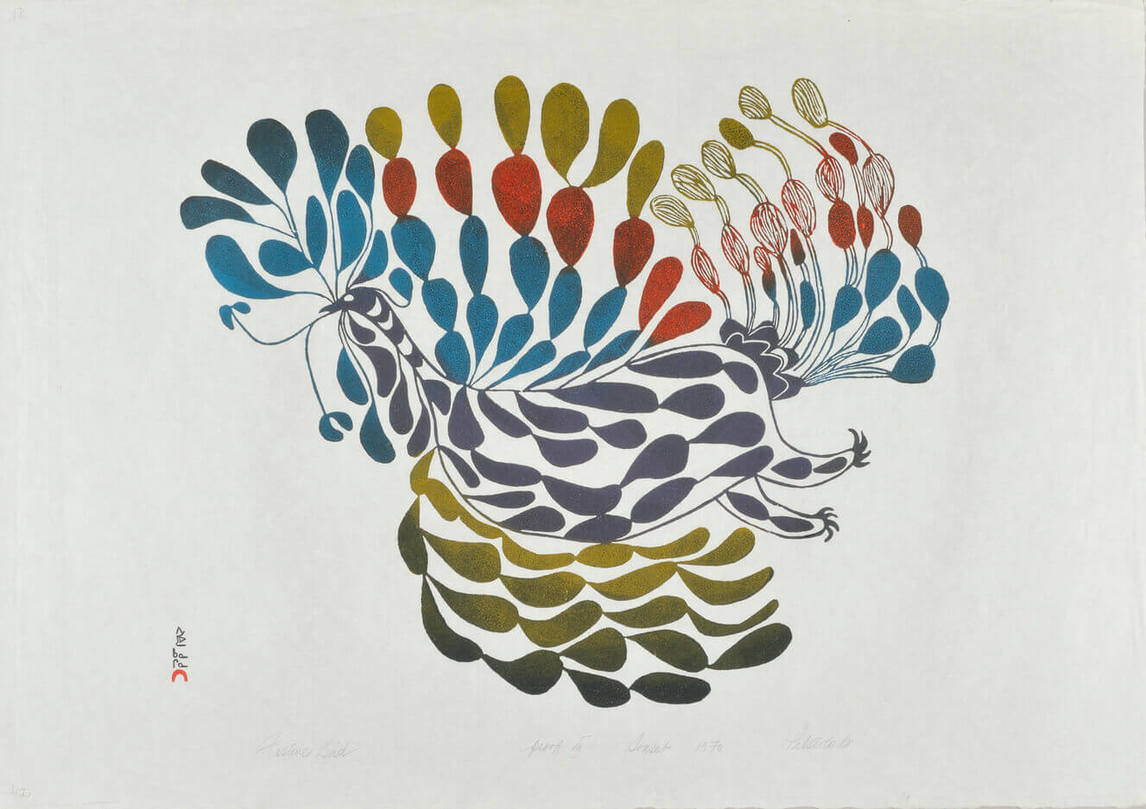

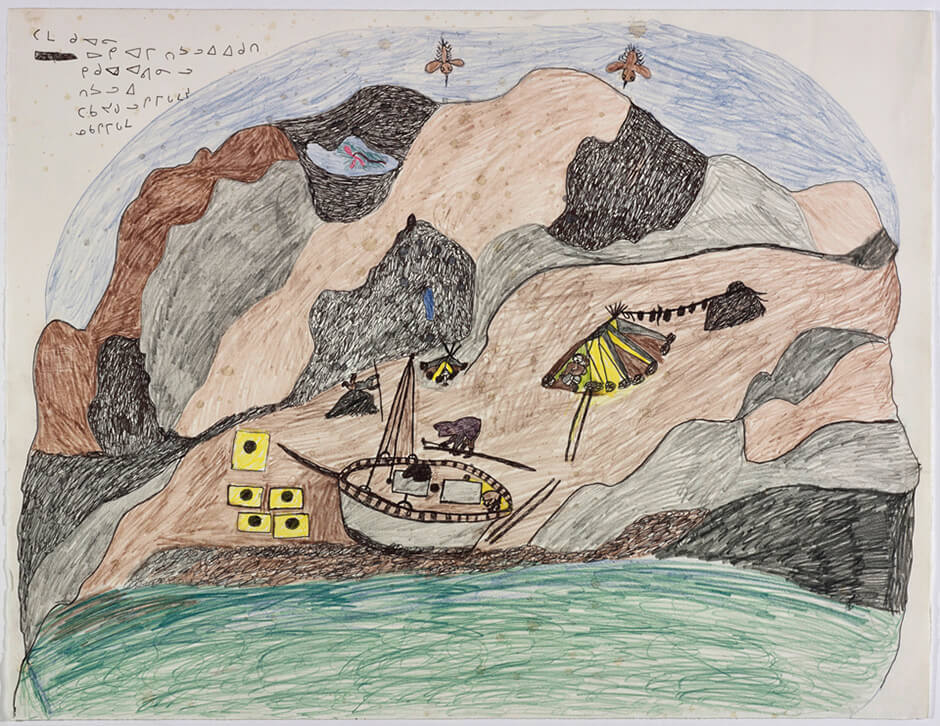

The popularity of the Cape Dorset prints, in particular, across Canada and internationally, contributed to the growing interest in Inuit art in the 1960s and 1970s. Pitseolak’s artwork, in its portrayal of Inuit culture and its aesthetic appeal, helped place Inuit art firmly within the Canadian psyche through widespread exhibitions and reproductions in publications. Within a broader art history, though rarely noted, the success of the prints based on drawings by Pitseolak and her contemporaries contributed significantly to the printmaking revival that took place throughout Canada in the 1970s.

Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit

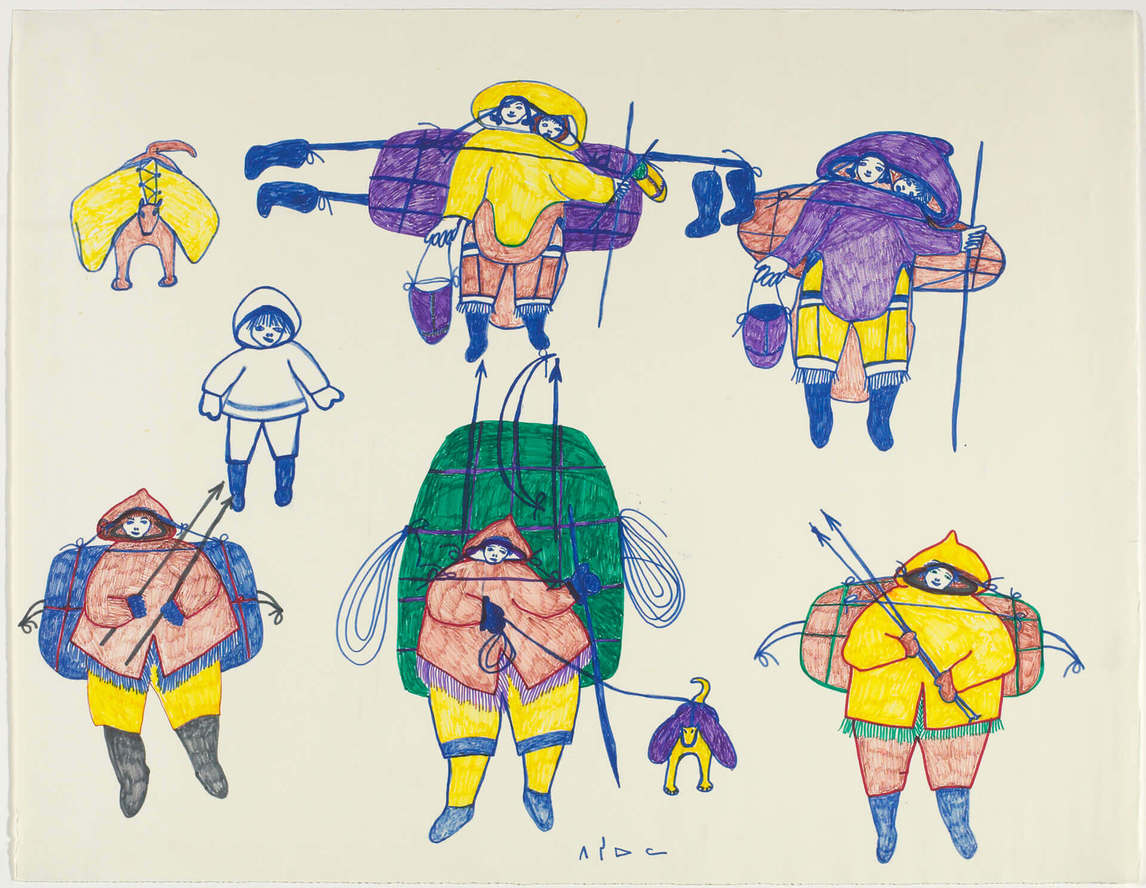

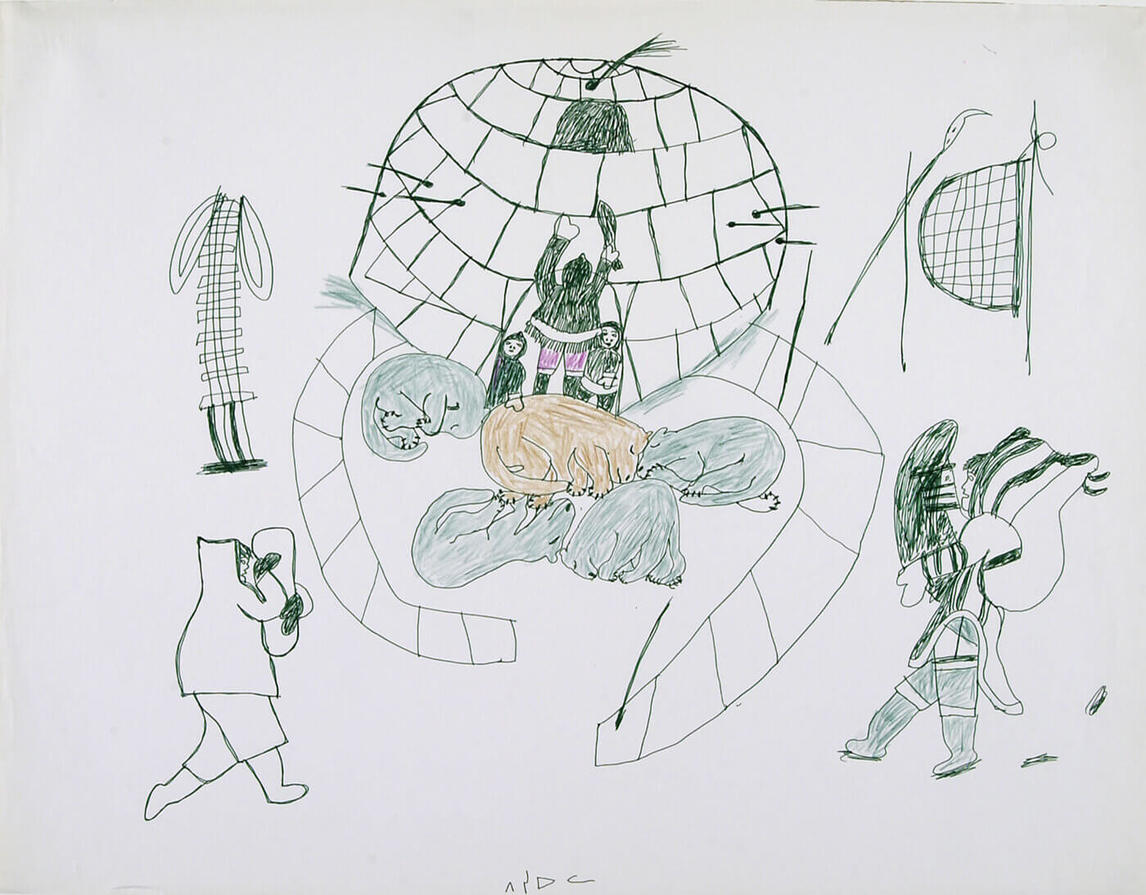

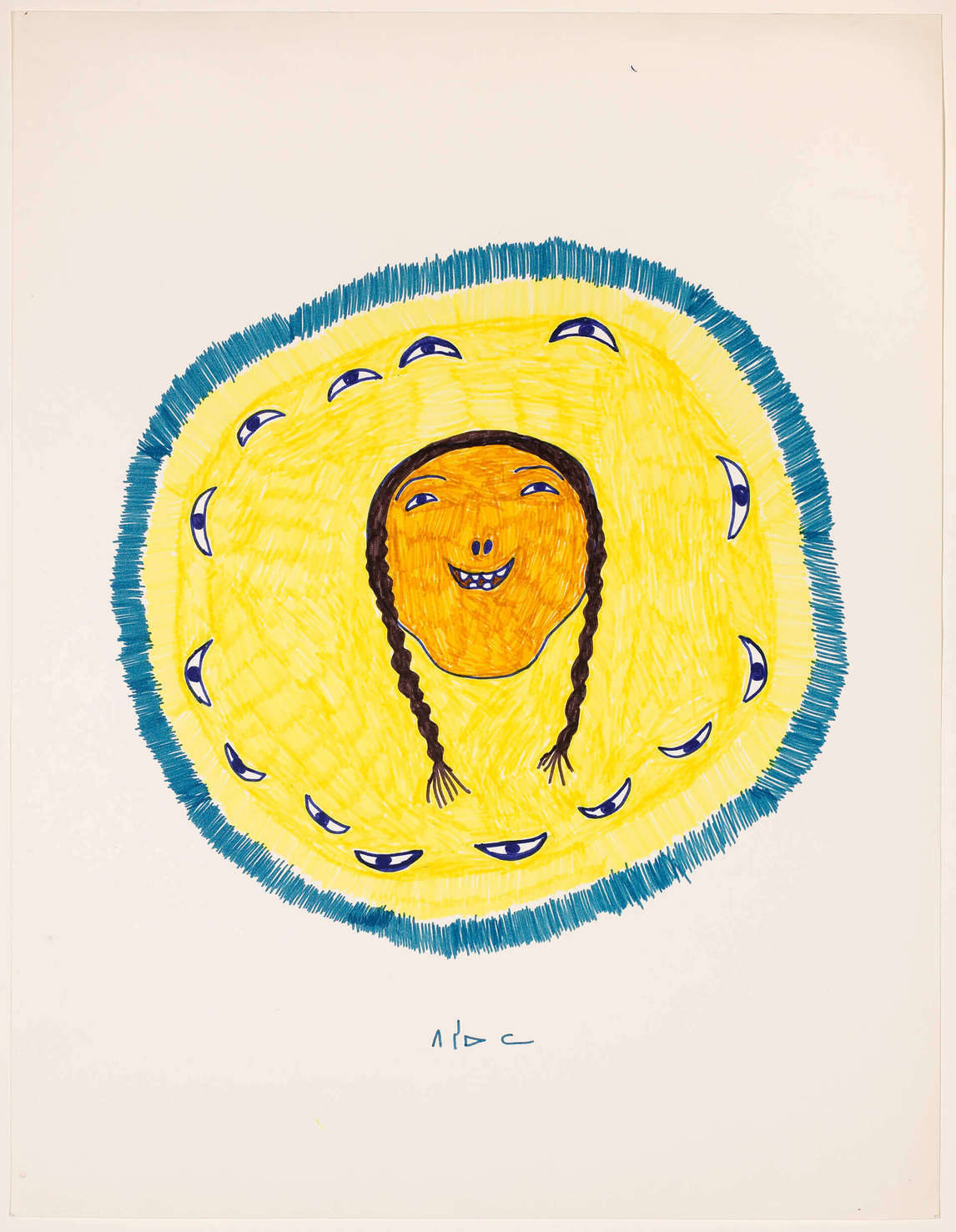

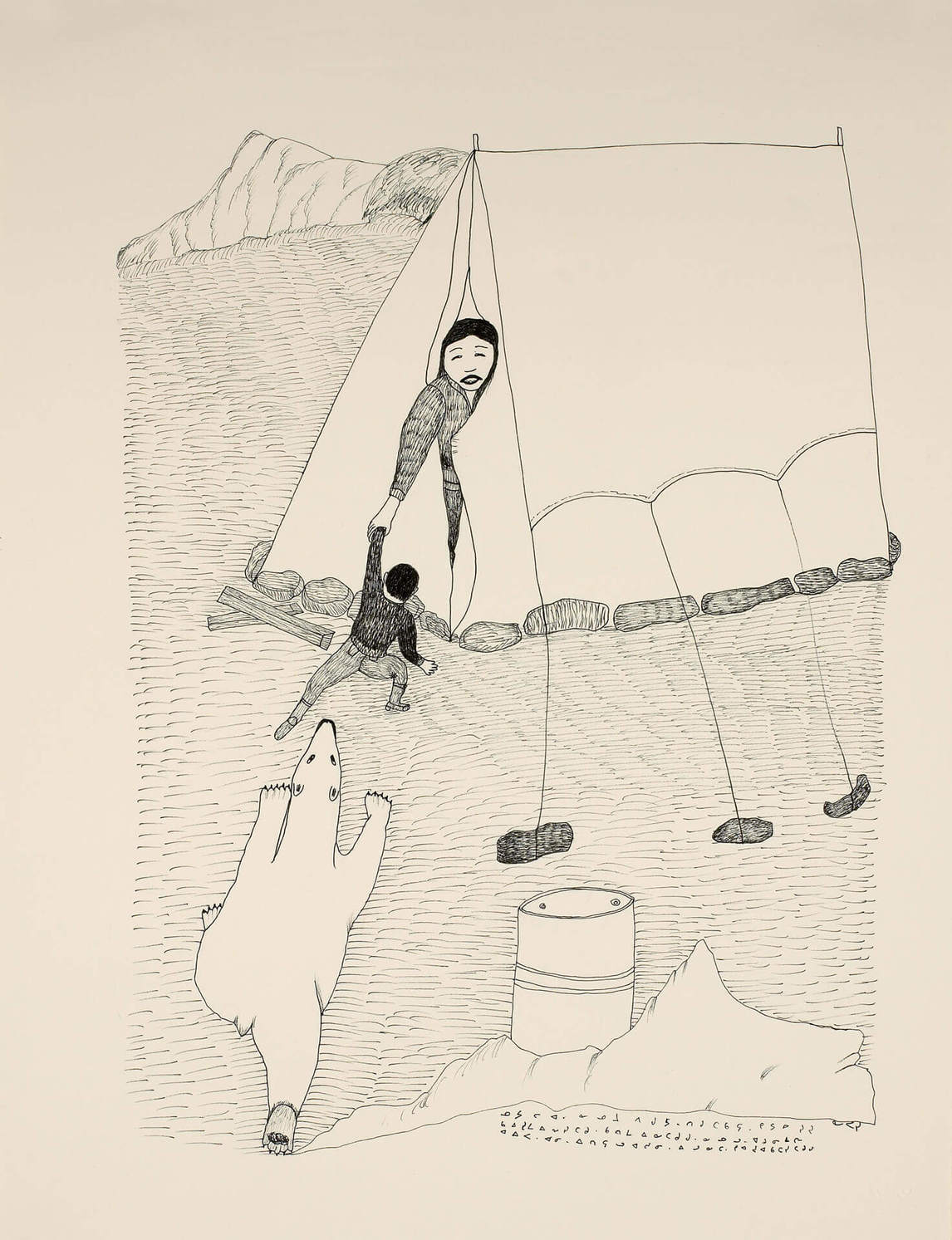

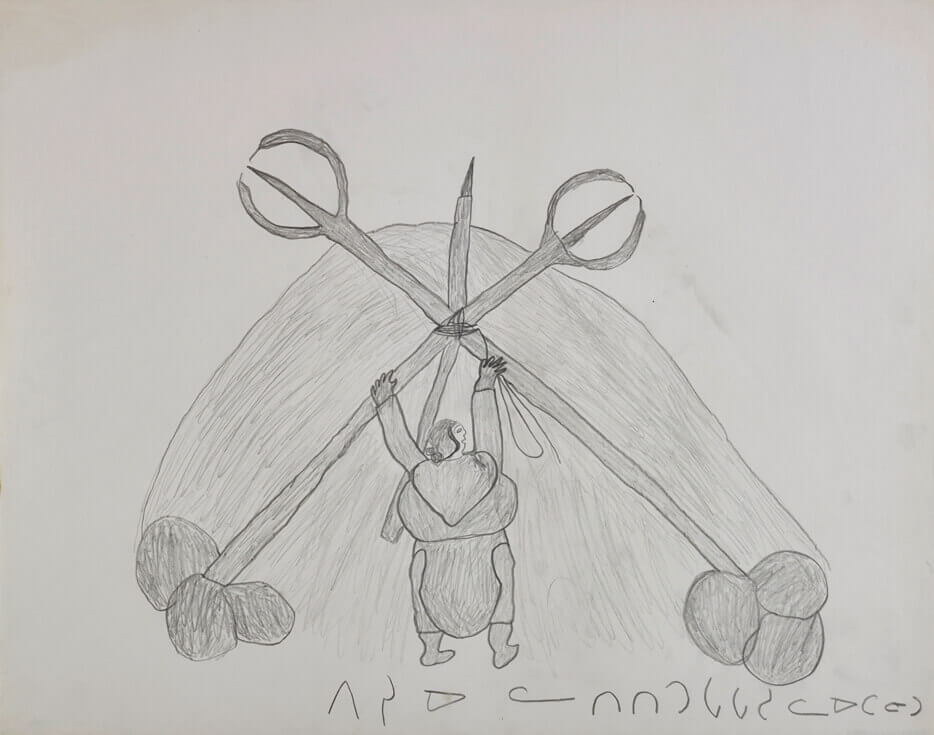

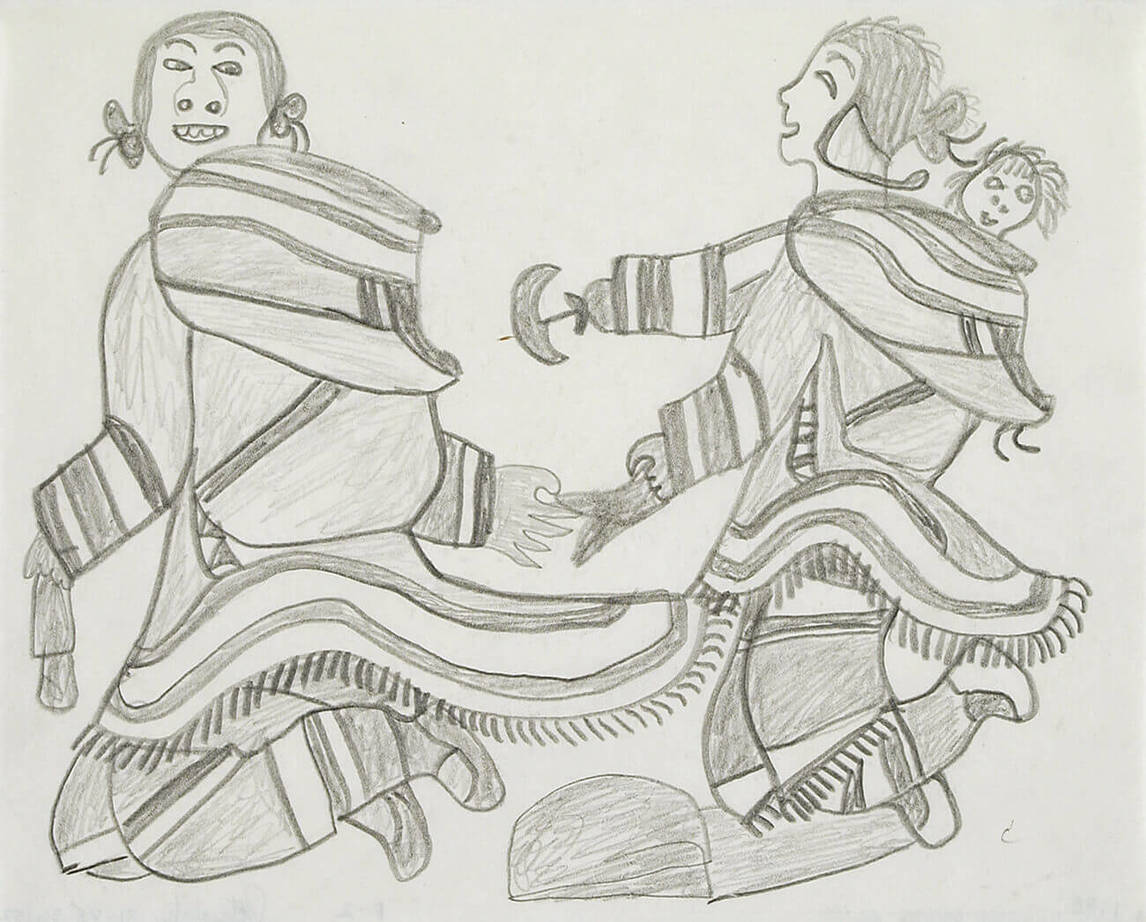

Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit is an Inuktitut phrase used to describe the knowledge and values passed down through generations as “things we have always known, things crucial to our survival.” Pitseolak’s drawings are important for their transmission of Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit, as well as for the pride they instill in a shared Inuit heritage within her community. Pitseolak understood art’s communicative power and was conscious that her drawings presented the intellectual, spiritual, and material culture of the Inuit to the rest of Canada and the world. The didactic quality of her art was motivated by her desire to teach others, non-Inuit and future generations of Inuit alike, about the life she experienced first-hand. Attesting to this, her son Kiugak Ashoona (1933–2014) observed, “My mother’s drawings show exactly the lifestyle we lived as Inuit in the Netsilik area.” Likewise, in Pictures Out of My Life (1971), she spends much time describing how Inuit lived and the wide range of necessary skills, from making skin clothing, kayaks, and shelters to catching birds.

Pitseolak chose not to dwell on the harsher side of camp life or the difficult transition to sedentary life in Arctic communities. Contemporary Inuit artists have begun to provide social and political commentary, but in Pitseolak’s time, artists instead focused on the strengths of traditional camp society and thereby transmitted knowledge that they were concerned might otherwise disappear.

Personal Narrative

The iconic cultural images created by the first Inuit artists quickly became themes that were carried forward by following generations. Pitseolak contributed to the establishment of this visual vocabulary, but she also laid the groundwork for the exploration of new subject matter through her autobiographical artworks. This critical influence can be traced through her daughter, Napachie Pootoogook (1938–2002), to her granddaughter Annie Pootoogook (1969–2016), whose own autobiographical work has redefined contemporary Inuit art.

A common perception of Inuit art from Pitseolak’s era is that the artists did not represent themselves or their families or events from their own lives. During her first decade as an artist, Pitseolak had a reputation for depicting the “old ways”; although her work was culturally specific and accurate, there was no expectation that she was referring to personal experience. With the publication of Pictures Out of My Life in 1971, her drawings were recognized for the first time for their autobiographical content. By the end of her life her reputation for this content was firmly established. The leading art historian and former Winnipeg Art Gallery curator Jean Blodgett notes this new perspective in Grasp Tight the Old Ways (1983): “Many Pitseolak works are imbued with a strong personal element illustrating actual people and events as she remembers them from her past.”

The intimacy in Pitseolak’s images is a large part of their appeal. Yet her drawings are ambiguous; there is rarely an obvious reference to her life. It may be that she represented herself differently from how a Western artist approaches self-representation. The reasons for this are twofold: first, as an artist, Pitseolak was encouraged by James Houston (1921–2005) and the growing market for “exotic” images of Inuit life to create representations that focused on a collective rather than an individual identity; and second, her concept of self was expressed differently from a sense of self informed by modern Western individualism.

For centuries, in the close-knit extended family groups of the camps, identity was shaped in large part by sharing and by naming practices. Strong bonds to others reinforced a sense of cohesive identity that was important to maintaining harmonious relations. Reflecting this, Pitseolak’s drawings, such as Eskimos on Sealskin Boat, c. 1966–72, though autobiographical, depict group activities without giving prominence to any one individual. Instead of communicating events as “this happened to me,” her images are presented as shared history—“this happened to us”—yet without denying her identity. From the outside, a collective society could be assumed to lead to anonymity; arguably, however, individuals in small communities tend to have a stronger sense of self than those in large urban centres.

Becoming an Artist

As one of the first artists to make drawings for the print studio in Cape Dorset in the early 1960s, Pitseolak had no instructors and few examples of artwork on paper to follow. Promotional booklets such as Canadian Eskimo Art by James Houston (1921–2005), published in 1964 by the Department of Northern Affairs and National Resources, indicated which types of art sold well in the market, but there was little or no information on techniques or pictorial devices. Visiting artists offered some training in specific media—such as in the early 1960s Alexander Wyse (b. 1938) introduced engraving in Cape Dorset, and in the late 1970s K.M. Graham (1913–2008) encouraged artists to explore the use of acrylics—but rarely did Inuit of Pitseolak’s generation have the opportunity to study art techniques or methods. Instead, Pitseolak worked out solutions to artistic problems—such as how to convey the movement of figures or place them within a landscape—through what can be described as a self-directed program of repetitious drawings. “Does it take much planning to draw? Ahalona! It takes much thinking, and I think it is hard to think. It is hard like housework,” she said.

For centuries leading up to and including Pitseolak’s own lifetime, Inuit made and perfected everything they needed for survival—from tools to sleds to shelter—through invention and adaptation of the material resources at hand. This required innovation through trial and error, through a process of learning by experimenting and hands-on practice. Inuit artists of Pitseolak’s generation had a similar approach to their artmaking; they proved to be resourceful, experimenting to find solutions that worked—though the process was complicated by there being no measurable, physical function with art. The ingrained experimental approach allowed them to excel in diverse media. Each artist had to invent his or her own style to convey ideas, which is reflected in the wide stylistic range and the directness of expression that typifies Inuit art.

Unlike many Inuit artists who work solely within a style established early in their careers, Pitseolak followed a process of continuous experimentation, from early roughed-out drawings with an emphasis on line, to flamboyant well-composed scenes in rich colour, to the more subdued and refined quality of her last works.

Working largely outside of Western art traditions, Inuit artists were categorized as “naive” or “primitive” in their style and approaches to making art, as in a 1969 description of Cape Dorset drawings as “childlike drawings in nursery colours… like innocent documentary.” Countering such clichés, Pitseolak’s self-directed efforts toward developing her visual expression were consistent with those of an artist with formal arts training and brought recognition to the validity of Inuit systems of learning.

Inuit Women as Artists

Inuit women were readily accepted as artists in northern communities and among the supporters of the new art forms, such as James Houston (1921–2005), Alma Houston (1926–1997), and Terrence Ryan (1933–2017) in Cape Dorset; and art galleries in cities across Canada and internationally. Because there were no preconceived ideas about how artmaking fit within traditional gender divisions of labour, women were able to participate actively in new economic ventures through arts and crafts programs. Women were empowered by becoming artists, and by their new roles as visual historians and breadwinners in the changing Inuit society.

Representations of women and their activities by male artists provide a male perspective and often convey an objective respect. Only the images of women by women, however, can be said to give voice to female identity. The visual history of Inuit culture would be incomplete without the contributions of artists such as Pitseolak. Her images of women’s tools, motherhood, and domestic scenes illuminate the role of women within Inuit society.

In traditional Inuit culture the clear delineation of activities and a person’s ability to perform tasks—such as hunting, for men, and sewing, for women—reinforced the sense of self in the larger community. Pitseolak’s many images of women at work are more than a visual record of the tasks depicted. Through them, she communicates the vitality and strength of Inuit women. She expresses the camaraderie of women sharing tasks, as they depended on each other while the men were absent on hunting trips, often for long periods. This camaraderie is show in works such as Women Gutting Fish, c. 1960–65.

Pitseolak’s images of women’s implements are carefully organized to demonstrate and share her knowledge of these tools. In many drawings, her depictions of the ulu, the woman’s knife, and other tools, become a metaphor for woman, reflecting how closely an Inuit woman’s identity is bound up in her work.

Inuit women of Pitseolak’s generation typically gave birth to many children; she herself had seventeen. Not surprising then, her work strongly reflects the importance of motherhood to female identity. Children are ever present as women perform their daily activities, as seen in Summer Camp Scene, c. 1974.

The peak of Pitseolak’s artistic production, in the mid-1970s, coincided with the international women’s movement and a questioning of the gender inequality evident in the arts. In this context, Pitseolak was celebrated for her role and influence as a leading artist and a matriarch within a family of artists. A decade after her death, Canada Post included her portrait in a series of stamps honouring Canadian women and issued on International Women’s Day in 1993.

The Ashoona Legacy

Motivated at least in part by memories of the destitute years following the death of her husband, Ashoona, Pitseolak encouraged her children to take up artmaking, either drawing or carving. Through her example she instilled in them the drive to excel as artists by challenging themselves technically and stylistically. It is not by chance that all of her sons took up stone carving with a steady work ethic. In 1953 Qaqaq Ashoona (1928–1996) and Kiugak Ashoona (1933–2014) were included in the landmark exhibition organized by the London art gallery Gimpel Fils to commemorate the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II—the exhibition that introduced Inuit art to England. Both artists had lifelong careers and are recognized today as master carvers.

Pitseolak had a close relationship with her only daughter, Napachie Pootoogook (1938–2002), and they often drew together. Stylistically Napachie learned from her mother’s efforts, and some of her drawings from the 1960s are almost interchangeable with those by Pitseolak. Interestingly, after her mother’s death in 1983, Napachie’s style changed and began to move in new directions.

Pitseolak’s encouragement extended to her daughters-in-law: Sorosilutu Ashoona (b. 1941) remarked, “My husband’s mother asked me quite a few times to draw. She’s the one who really started me drawing—me and her two other daughter-in-laws—Mayureak [Mayureak Ashoona (b. 1946)] and Mary. They draw too because of her.”

From Pitseolak’s lead, the Ashoona name became synonymous with artistic excellence; recognition came as early as 1967, in the exhibition Carvings and Prints of the Family of Pitseolak held at the Robertson Galleries in Ottawa and including one hundred artworks. In his introduction to the 1979 Cape Dorset annual collection, James Houston (1921–2005) noted: “In Pitseolak we have the nucleus of a remarkable artistic family whose members play an important part in the artwork of Cape Dorset.”

Pitseolak’s artistic legacy continues through Annie Pootoogook (1969–2016), Goota Ashoona (b. 1967), and Shuvinai Ashoona (b. 1961), who spent much time with Pitseolak, and extends to more than a dozen grandchildren and great-grandchildren who are engaged in the arts.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements