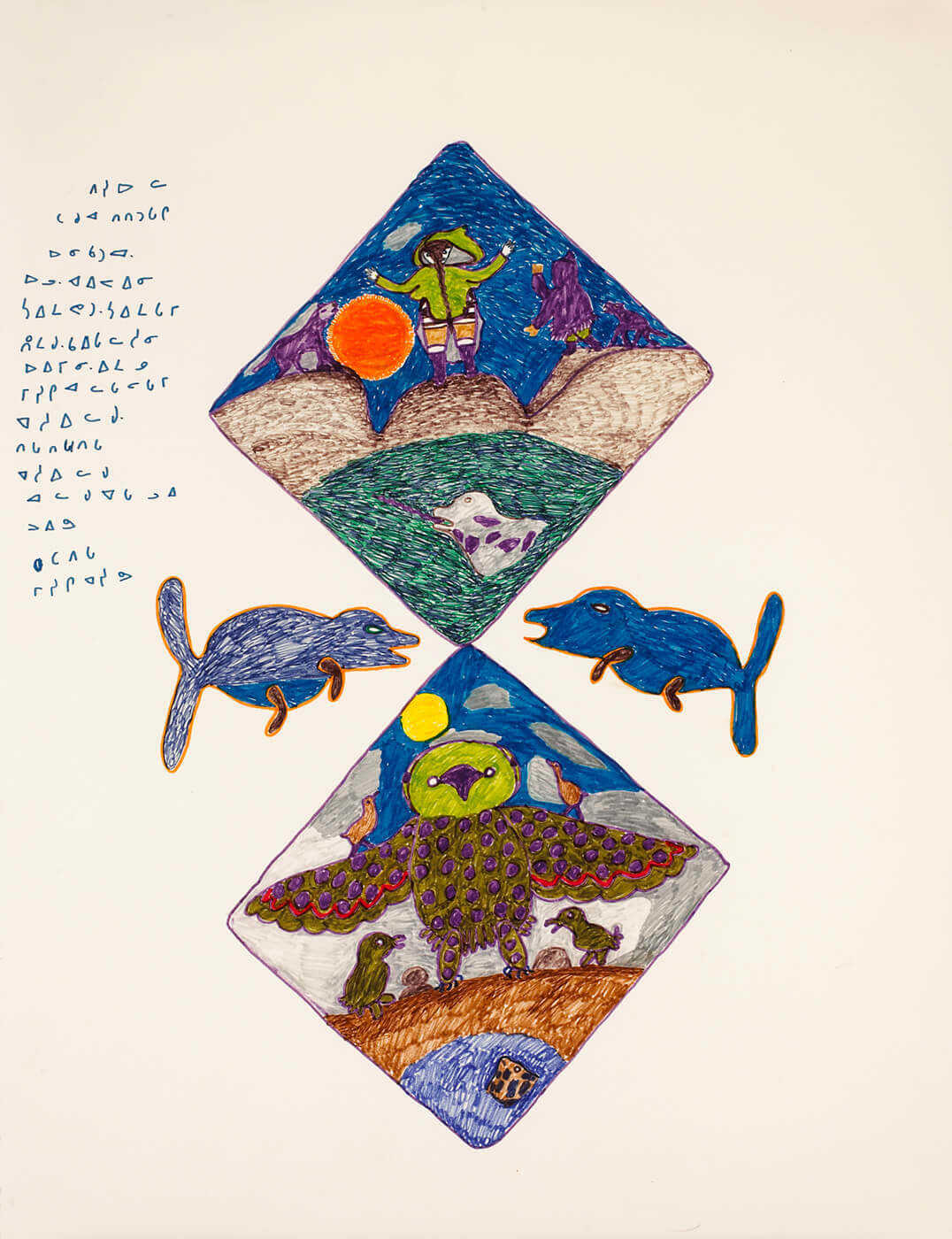

Legend of the Woman Who Turned into a Narwhal c. 1974

Pitseolak Ashoona, Legend of the Woman Who Turned into a Narwhal, c. 1974

Coloured felt-tip pen on paper

66 x 50.7 cm

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

Pitseolak occasionally drew on the legends she heard in her youth, particularly from her father, Ottochie. This gem-like drawing has all the hallmarks of her work—Inuit and animals in a landscape setting, portrayed in rich colour and using a vibrant line. Here Pitseolak experiments with unusual compositional devices, placing the scenes within diamond-shaped frames and balancing these one on top of the other.

The scene in the upper part of the drawing depicts a critical moment in the story of the woman who became a narwhal. Pitseolak’s version may be a variation from Nunavik (Arctic Quebec), where her father’s family originated, with her own personal emphasis. Along the side she writes the following in syllabics: “These are Pitseolak’s drawings. Every few days she would manage to be patient enough from the beatings she received from her husband. One day by the sea she was about to be beaten again. So she prepared to jump into the sea. At that moment all the narwhals rose to the surface of the water in front of her.”

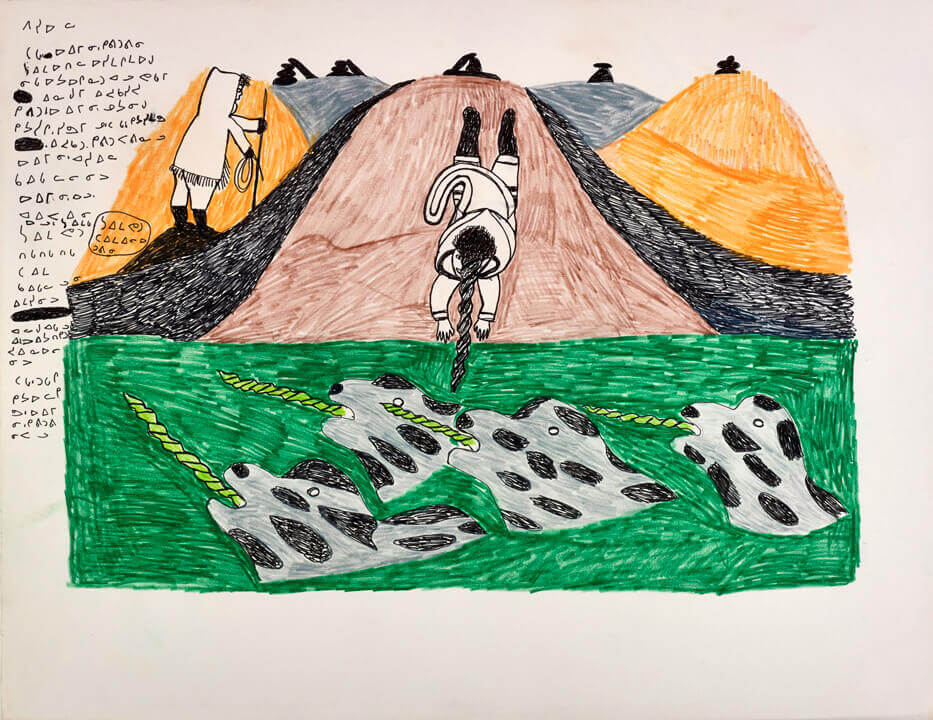

To escape her husband’s abuse, the woman jumps off a cliff; she does not die but is instead transformed into a narwhal. Pitseolak depicts the moment of transformation that saves the woman, with her long braid twisting into the tusk of a narwhal.

Pitseolak retells a legend in her drawing, but her focus on this version of the story is a rare instance of her depicting one of the hardships that she and many other women faced in camp life. Her daughter, Napachie Pootoogook (1938–2002), was aware of her mother’s circumstances, even illustrating an incident in Pitseolak’s Hardships #2, 1999–2000, in which her mother was beaten while another person attempted to take her first child. Pitseolak herself, however, never revealed such experiences either in her art or in interviews with individuals outside of the community.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements