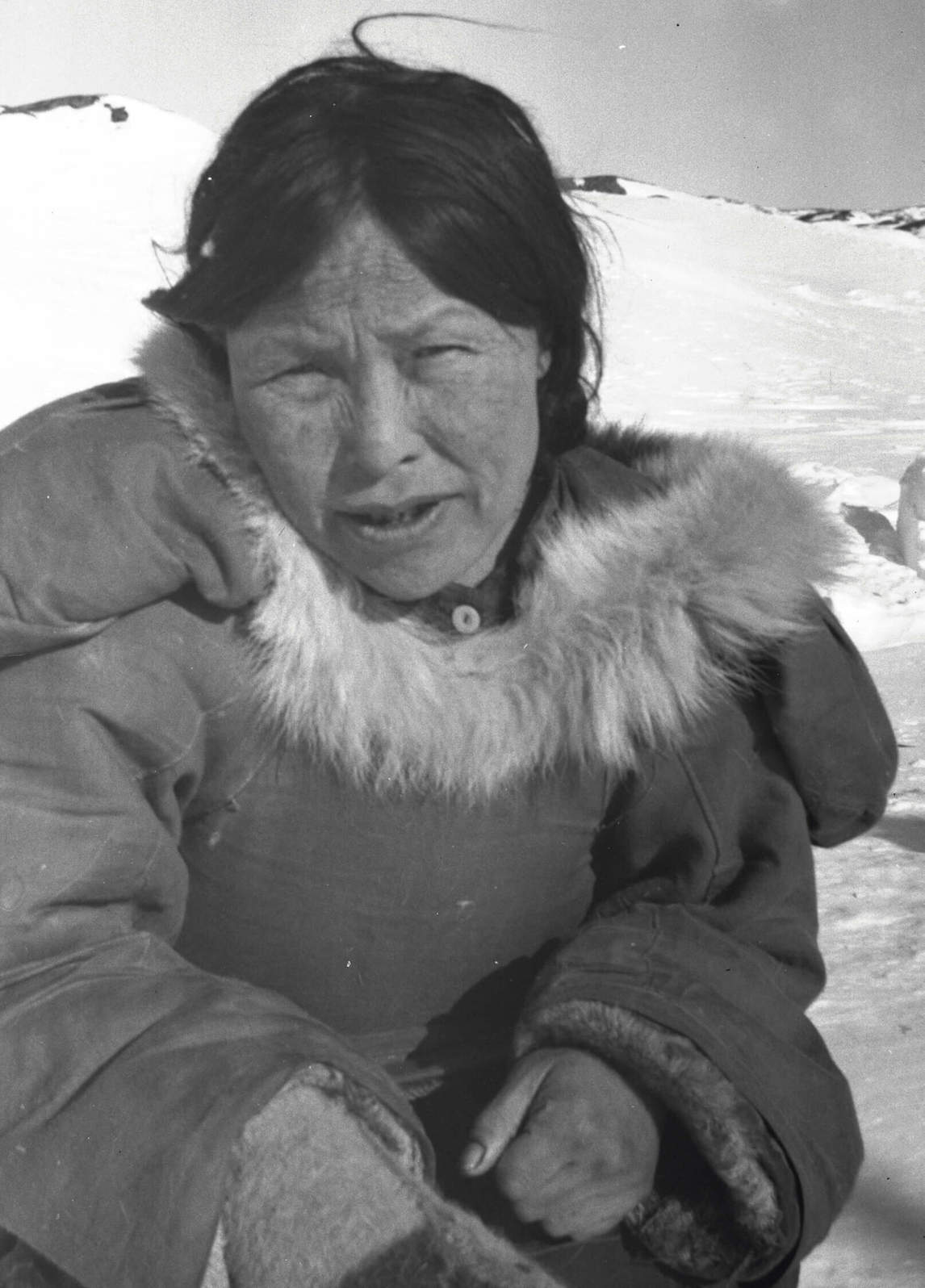

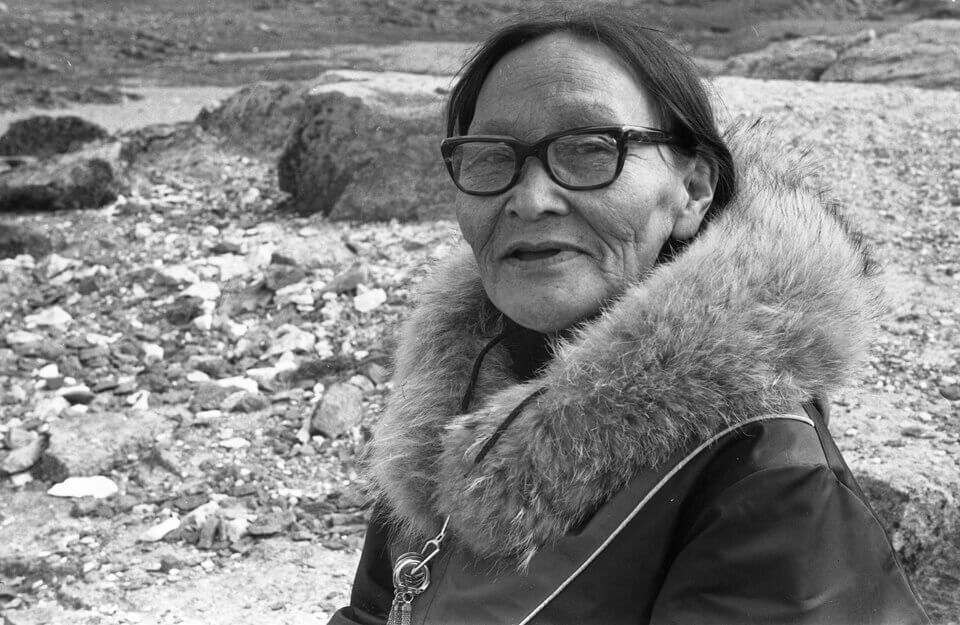

Pitseolak Ashoona had “an unusual life, being born in a skin tent and living to hear on the radio that two men landed on the moon,” as she recounts in Pictures Out of My Life. Born in the first decade of the twentieth century, she lived in semi-nomadic hunting camps throughout southern Qikiqtaaluk (Baffin Island) until the late 1950s when she moved to the Kinngait (Cape Dorset) area, settling in the town soon thereafter. In Cape Dorset she taught herself to draw and was an active contributor to the annual print collection. By the 1970s she was a world-famous artist, with work exhibited across North America and in Europe. She died in 1983, still at the height of her powers.

Early Years

In Pictures Out of My Life, an illustrated book of edited interviews with the artist, Pitseolak Ashoona recounts that she did not know the year of her birth. Based on various documents and stories handed down in the family, she is believed to have been born in the spring sometime between 1904 and 1908 at a camp on the southeast coast of Tujakjuak (Nottingham Island), in the Hudson Strait. Her parents were Ottochie and Timungiak; Ottochie was the adopted son of Kavavow, whose family originated in Nunavik but was expanding across the strait. At the time of Pitseolak’s birth, her parents and older siblings were en route from the Nunavik region of Arctic Quebec to the south coast of Qikiqtaaluk (Baffin Island). They were making the arduous crossing over land and water to be closer to Ottochie’s family and better hunting as well as trapping for the fur trade.

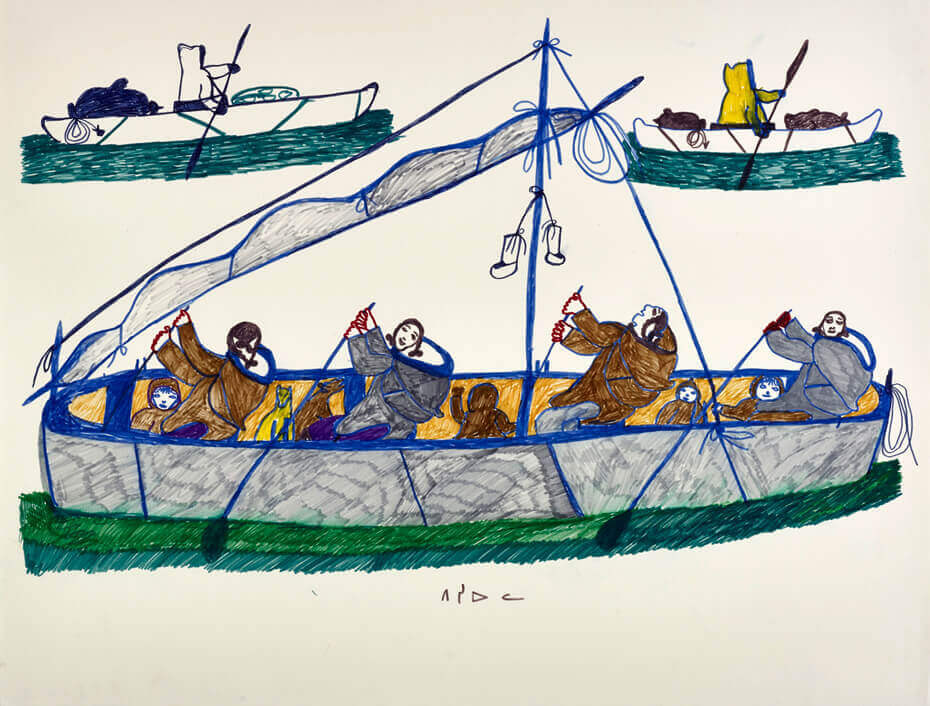

The family stayed at Tujakjuak until the following spring, crossing over to Tuja, a camp on Akudluk (Salisbury Island), before landing on the main island of Qikiqtaaluk, possibly on board the whaling ship Active for the last part of the journey. During the first years of her life, Pitseolak’s family continued to move along the southern coast by umiaq (sealskin boat), following the shoreline to Seengaiyak, a camp above present-day Iqaluit, and possibly as far as Cumberland Sound on the other side of Qikiqtaaluk.

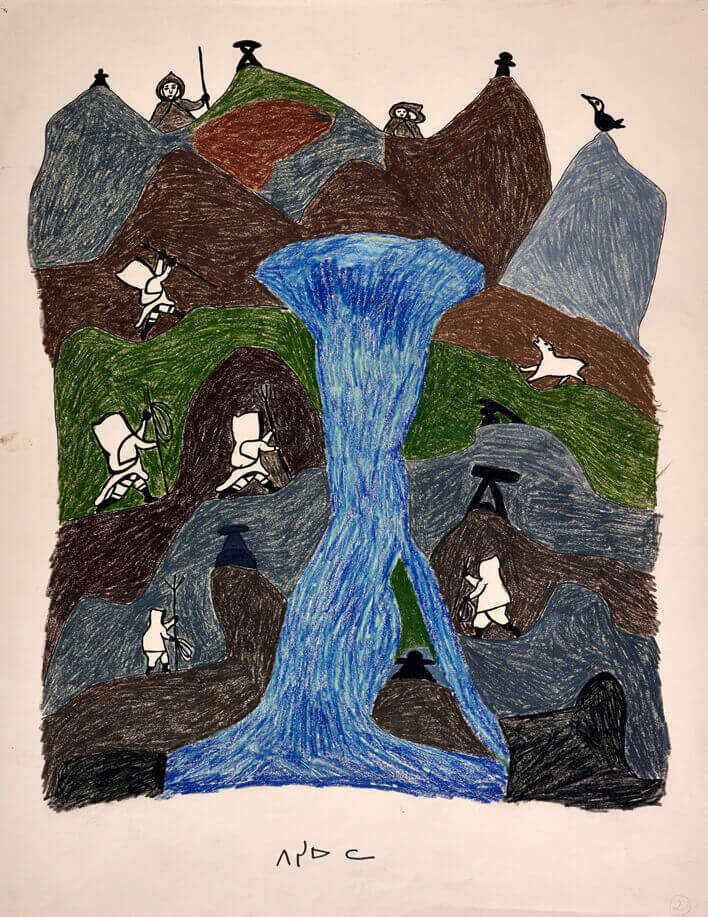

By the time she was five or six, Pitseolak had travelled with her family thousands of kilometres along the southern coast of Qikiqtaaluk. Travelling these distances by umiaq and dog team and qamutiq (sled), as well as on foot, Inuit developed a profound knowledge of the landscape—one that would later inform and inspire Pitseolak’s art.

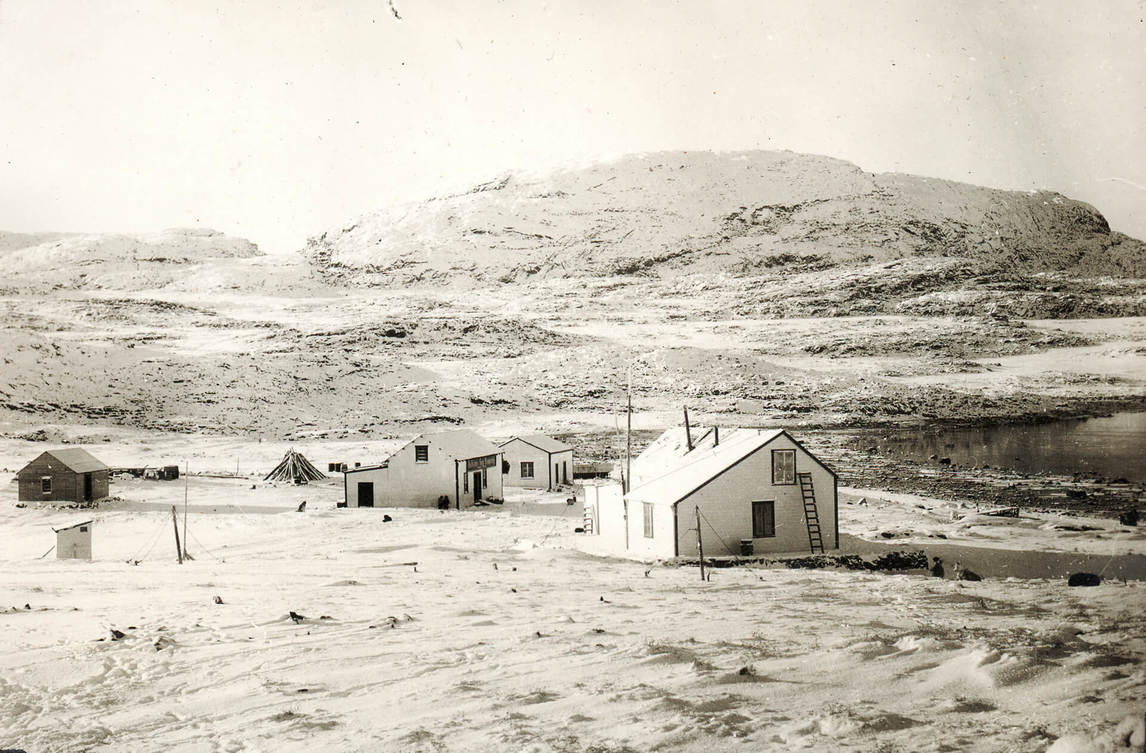

Returning to the Foxe Peninsula around 1913, they joined other family members in the area, living in outlying camps with groups that ranged from immediate relatives to as many as fifty people. That same year, a Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) post was established in what would become Cape Dorset, and while Pitseolak’s family hunted seasonally they also trapped fox to trade furs for goods at the post. With the decline of whaling and the rise of the fur trade, which flourished with the demand for white fox in Europe and elsewhere, by the 1920s seventy trading posts had been established across the Arctic. Inuit prospered from the competition between HBC and other traders, such as the Baffin Trading Company in Cape Dorset.

During prosperous years, with fur trapping supplementing subsistence hunting, the family thrived. Their encounters with the outside world—mostly ships and their crews—were largely positive. Pitseolak remembered as a young girl playing on the wreck of the Polar Star, which had sunk off the coast in 1899, and the useful materials such as wood that could be salvaged. Later, Ottochie was among those who worked on board the Bowdoin, an Arctic exploration schooner that was iced in at Idjirituq (Schooner Bay) during the winter of 1921–22.

The family’s prosperity came to an end with the death of Ottochie the same year. “My father is the first person I remember dying. I was very young, and I was with him when he died,” she recalled. Pitseolak’s uncle Kavavow arranged for her marriage to Ashoona, whom she had known since childhood. The union however, was initially a frightening one, which she recounted years later:

When Ashoona came to camp I didn’t know why he came. I didn’t know he came for me. I thought he’d just come for a visit—until he started to take me to the sled. I got scared. I was crying and Ashoona was pushing and sometimes picking me up to try to put me on the [sled].… The first time I was sleeping beside my husband his breath was so heavy, his skin so hard. But after I got used to my husband I was really happy; we had a good life together.

As was the custom, Ashoona brought Pitseolak and her mother to his relatives’ camp at Ikirasaq. They were married in a Christian ceremony in Cape Dorset in 1922 or 1923 by the Anglican clergyman known as Inutaquuq.

Married Life

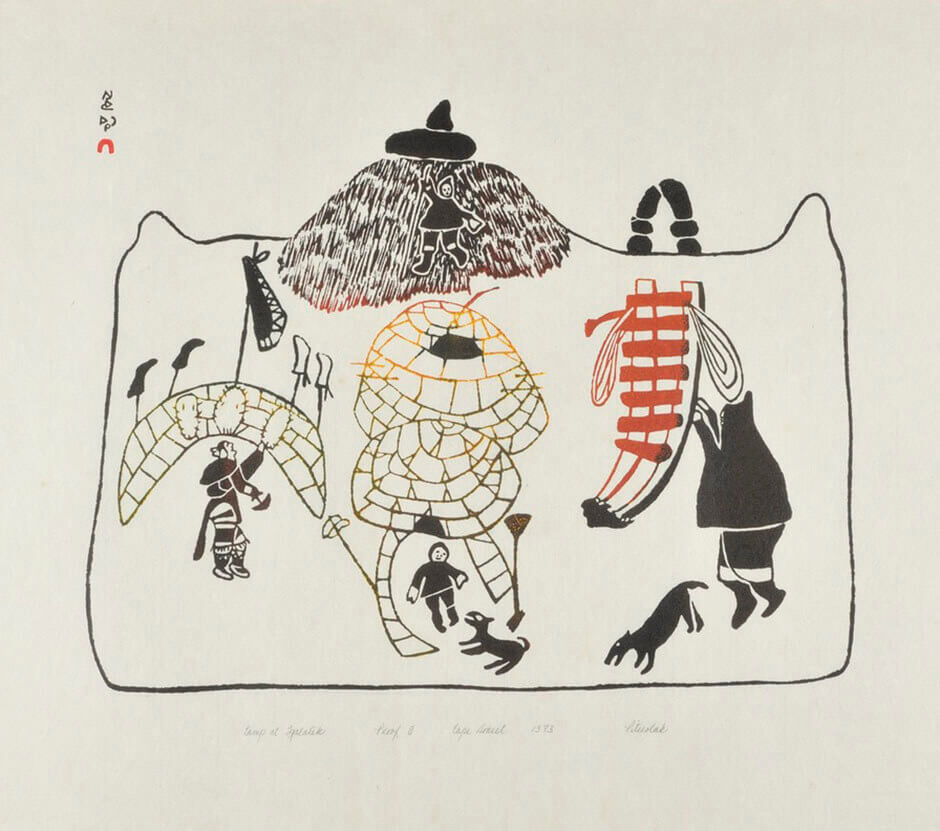

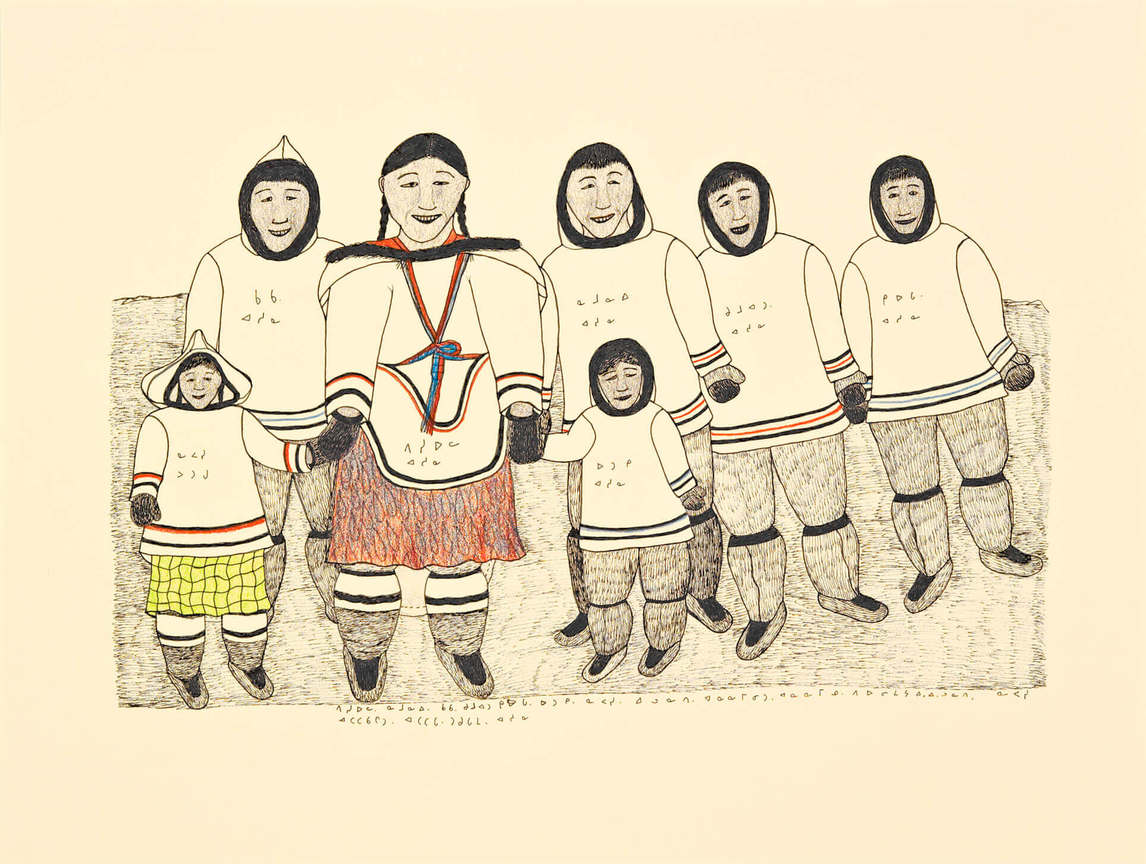

Pitseolak and Ashoona moved between camps up to ten times a year, following the seasons and animal migrations. Travelling between the main camps of Tariungajuk in the fall and Igalaliq in the summer, they would spend time at Tujakjuak, Akudluk, Ikirasaq, Idjirituq, Iqsaut, Qaqmaaju, and Netsilik. They left Ikirasaq, the main camp, before their first child, Namoonie, was born on Akudluk Island. Pitseolak gave birth to seventeen children, one each year of her marriage to Ashoona, though only six—Namoonie, Qaqaq, Kumwartok, Kiugak, Napachie, and Ottochie—lived with her until adulthood. Some died in childhood, and others were adopted out, as was customary, and raised by other Inuit families.

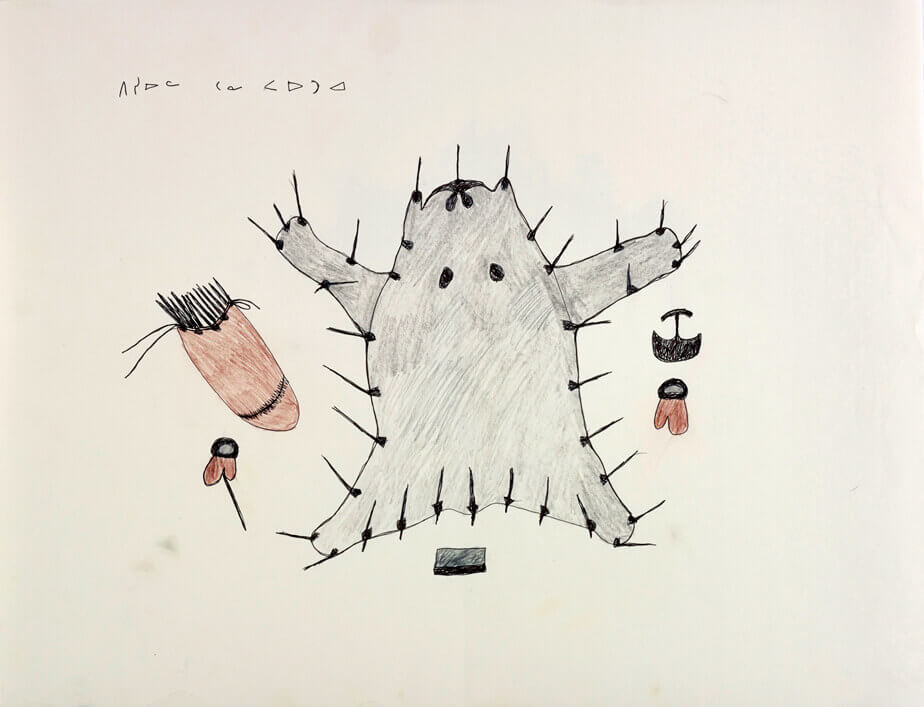

Pitseolak’s life during the 1920s and 1930s was fully occupied with her growing family. The family depended on her abilities to prepare skins and sew weatherproof shelter and clothing, including waterproof footwear, which was key to survival in the Arctic. As her son Kiugak Ashoona (1933–2014) recounted, “My mother was only one person who was looking after so many children and also her husband. And she would make parkas out of caribou skin. So it was just one lady with a needle and a lot of thread, making parkas for all of her children and her husband!”

Ashoona was recognized as a capable man and a strong hunter; he led the family to distant inland camps such as those around Nettilling Lake. Pitseolak recalled their isolation in the early years there: “The first time I went to Netsilik we were all alone for a year, and Ashoona delivered my son Kumwartok. With my mother’s help.” In an interview in 1979 Kumwartok explained, “It seems like only the men who were really men—who were really good hunters—would go to Netsilik because it was so far from shore.” Ashoona occasionally left the family to serve as a guide; he worked for the naturalist J. Dewey Soper on at least one of his treks in search of the blue goose nesting grounds. According to Kiugak, Ashoona may also have worked at the weather station on Tujakjuak and helped with map-making during the early years of the Second World War, just before his death.

Pitseolak never dwelled on the difficult aspects of camp life: “This was the old Eskimo way of life; you couldn’t give up because it was the only way. Today I like living in a house that is always warm but, sometimes, I want to move and go to camps where I have been. The old life was a hard life but it was good. It was happy,” she recalled. Decades later, she drew on these years as source material for her artwork.

Sometime in the early to mid-1940s Ashoona died during an illness when the family was at the Netsilik camp. Echoing Pitseolak’s experience of the loss of her father, the death of her husband, the principal hunter for the family, marked the beginning of a period of hardship for her and her children. It coincided with the early years of the Second World War and a decline in the market for furs. The ensuing financial and social instability made it difficult for community members to support the widowed Pitseolak and her six children in their camps. Her daughter Napachie Pootoogook (1938–2002) recalled this time: “My mother used to try her best to make it so we could have something to eat. But we used to be hungry after my father died.”

After Ashoona’s death Pitseolak left the inland camps and took her family to Cape Dorset to be near relatives; she discovered, though, that her relatives had either died or moved away. The next several years were difficult, but the family persevered. The art historian Marion E. Jackson describes how they lived, based on her interviews with Pitseolak and the Ashoona family:

In the lean years following Ashoona’s death, Pitseolak and her growing children lived in camps with other families. Gradually, her sons grew stronger and became good hunters. In time, they were able to provide the food and skins needed by their mother. As they married and started their own families, Pitseolak lived with her sons in the outlying camps, eventually spending her final years in the household of her son Koomuatuk [Kumwartok] when they moved into permanent housing in Cape Dorset in the early 1960s.

The transition from life on the land to settlement living—the most drastic change to Inuit society in the twentieth century—was met by Pitseolak with resolve and an optimistic nature.

Ashoona’s death was a tragedy for his family, but it provided the catalyst that would eventually lead Pitseolak to become an artist. As she said decades later, “After my husband died I felt very alone and unwanted; making prints is what has made me happiest since he died.” Despite the impact of the years of hardship that followed his death, scenes of deprivation or suffering almost never appear in her drawings, though certain images convey sadness and longing at his passing. Pitseolak was one of the first Inuit artists to create openly autobiographical work, yet she focused almost completely on good memories and experiences.

Early Artmaking

In the 1940s and 1950s an Inuit widow, particularly with young children, would have remarried to maintain the complementary gender-related roles necessary for survival. It is unusual that Pitseolak never did and even more remarkable that she was able to eventually provide for her family by making art.

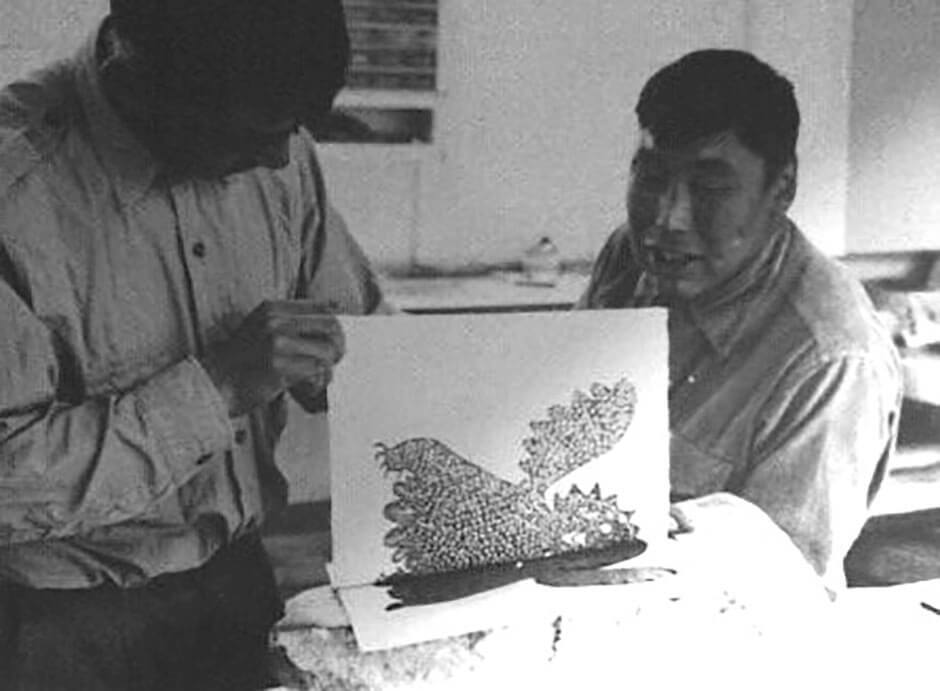

Her opportunity came with an arts and crafts program initiated in Cape Dorset by the department of Northern Affairs and National Resources (Indian Affairs and Northern Development after 1966) as an economic incentive for Inuit who were making the transition from subsistence hunting and trapping to a wage economy in settled communities. The artist James Houston (1921–2005) and his wife, Alma Houston (1926–1997), were instrumental in developing the program. James Houston first travelled to the Arctic in the late 1940s and returned to Montreal with a collection of small Inuit carvings. Encouraged by the Canadian Handicrafts Guild and grants from the federal government, the Houstons moved to Cape Dorset in 1956 to work with the Inuit.

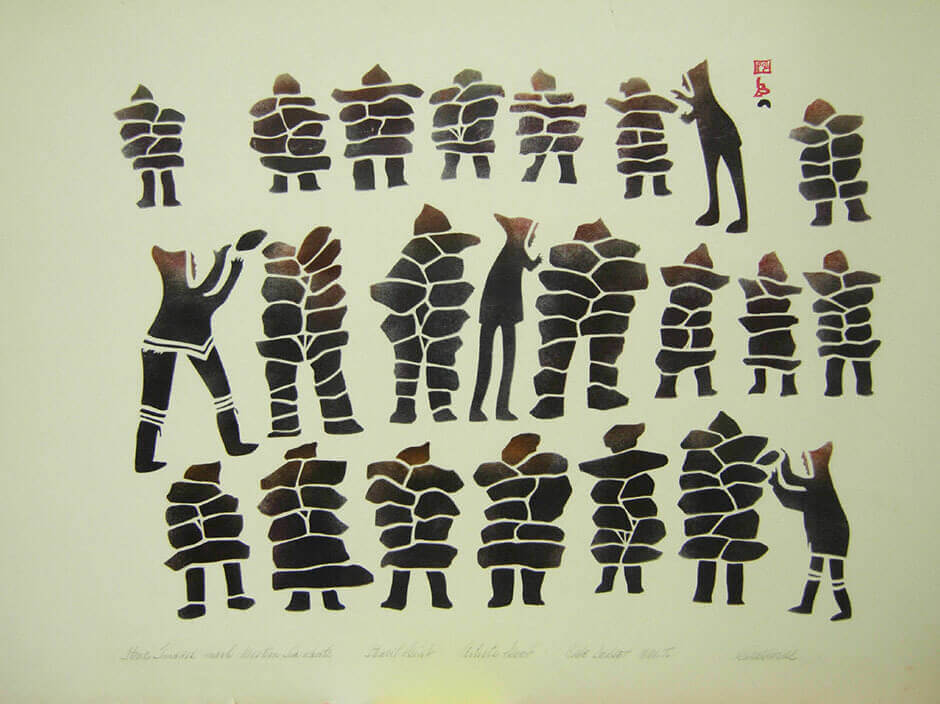

Although Inuit had carved small objects, usually in sea ivory, as a pastime for centuries, there was no precedent for drawing images on paper or printmaking, or for the notion of the artist as a role within the community. James Houston devoted his efforts to the introduction of printmaking and stone sculpting. Alma focused on the traditional skills of Inuit women and explored the potential for hand-sewn goods.

The sewing that Pitseolak had done throughout her life led her to work with Alma Houston on clothing production for sale in the developing market for Inuit arts and crafts. For two years Pitseolak made finely decorated parkas, mittens, and other items that were sold through the newly formed West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative.

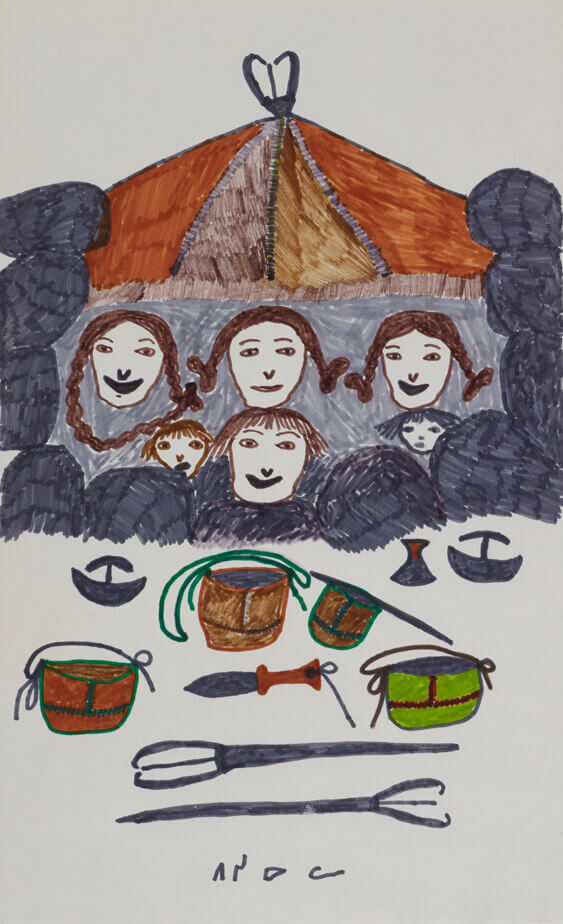

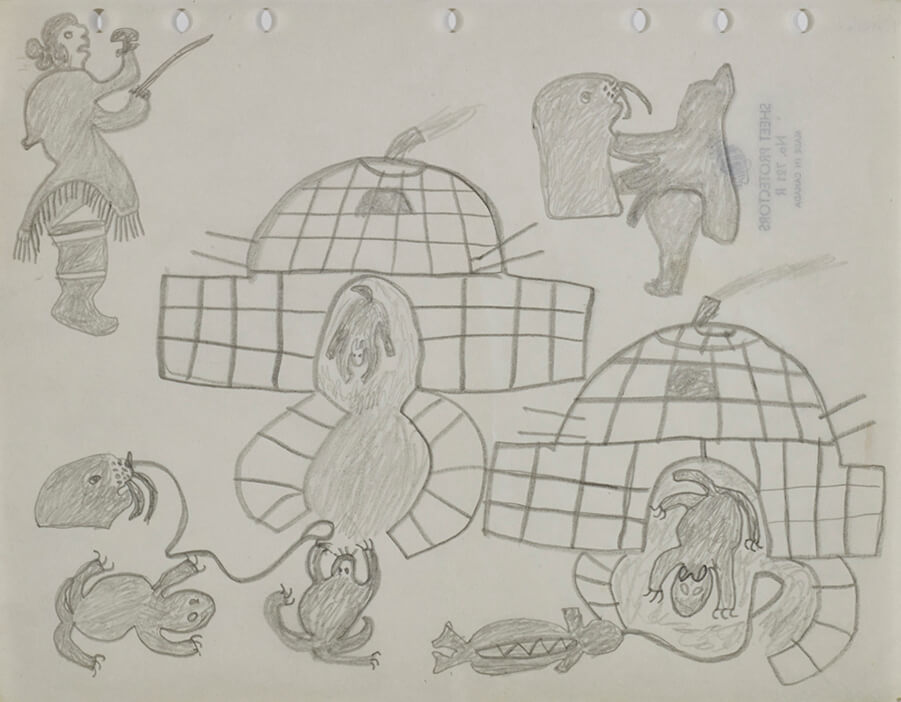

However, after seeing the drawings and prints created by her elder cousin Kiakshuk (1886–1966), and intrigued by the possibility of making a better income, Pitseolak decided to try drawing:

I started drawing after other people around here had already started. Nobody asked me to draw. Because my son’s wife died when their two children were very young, his children used to be with me. One night, I was thinking, “Maybe if I draw, I can get them some things that they need.” The papers were small then, and I drew three pages of paper. The next day I took them to the Co-op, and I gave them to Saumik, and Saumik gave me $20 for those drawings.… Because for my first drawings I got money, I realized I could get money for them. Ever since then, I have been drawing.

Her efforts were well received by James Houston, who encouraged her to continue, taking as her subject the traditional Inuit way of life. In the early 1960s Terrence Ryan (1933–2017) replaced Houston and went on to play a vital role in the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative, the printshop (now known as Kinngait Studios), and Dorset Fine Arts, the Co-op’s marketing division. Ryan also admired Pitseolak’s wide-ranging imagination and discipline and continued to support her artmaking efforts.

Thus began Pitseolak’s exceptional career. That her vibrant images were chosen to be editioned for the Cape Dorset print collection year after year is a tribute to her talent and speaks to the esteem in which she was held by those involved in the studio production and by the collectors. She made over 8,000 drawings, possibly closer to 9,000, of which approximately 250 were made into prints.

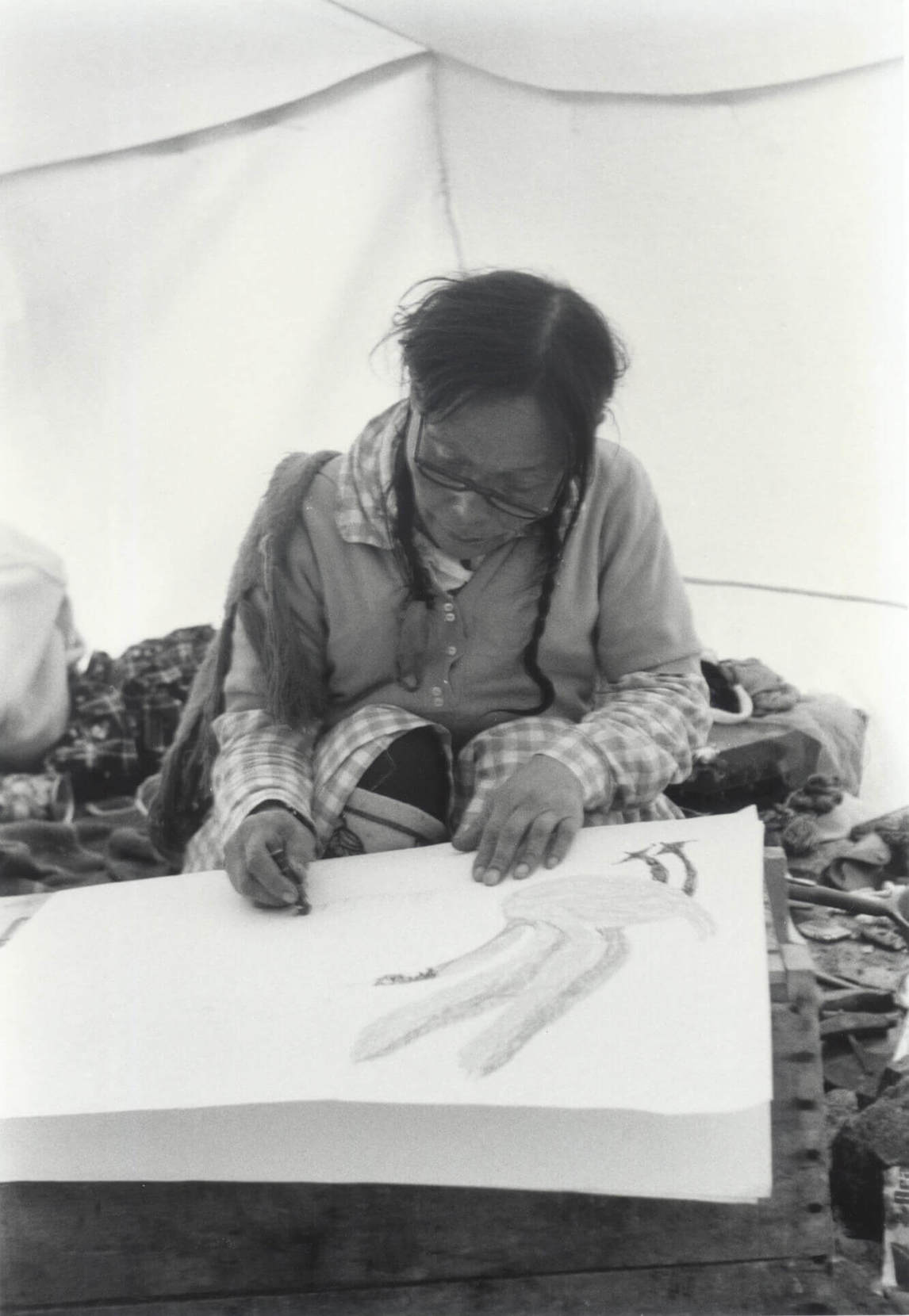

During the 1960s, while Pitseolak was actively creating successful work, she was constantly exploring her media, teaching herself how to draw. Beginning with graphite pencils on poor-quality paper, she developed the themes that she would return to and refine throughout her career. By the 1970s she had perfected her style and technique, and this later period represents her most resolved and successful drawings.

1970s: The Critical Decade

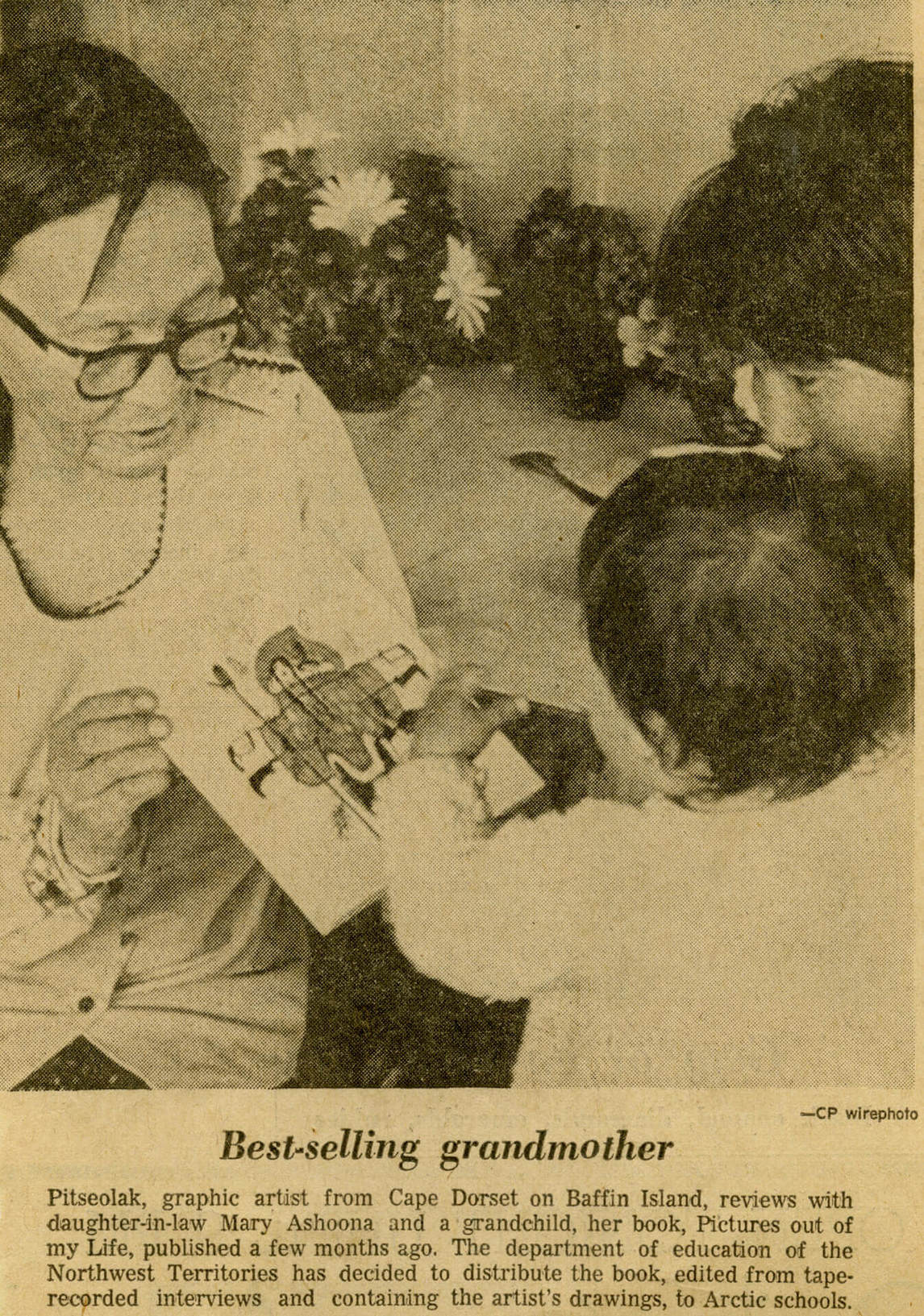

The 1970s was a period of great success for Pitseolak, both in the attention and honours she received and in her artistic production. The publication of Pictures Out of My Life in 1971 led to much wider interest in her life and work.

It is rare to have access to a detailed biography for Inuit artists of Pitseolak’s generation, much less a record of an individual’s thoughts and perceptions. The historian and writer Dorothy Harley Eber recognized that Pitseolak had a remarkable story to tell, and it is largely a credit to Eber and the Inuktitut translators she worked with that Pitseolak’s life is so well documented and recorded in the artist’s own words.

During a brief stopover in Cape Dorset in 1968, her first trip to the community, Eber interviewed Pitseolak, among other artists. After meeting Pitseolak, she decided to return and do more interviews. In the summer of 1970 Eber spent three weeks with Pitseolak as she recounted events from her life, with the assistance of two translators, Quatsia Ottochie and Annie Manning.

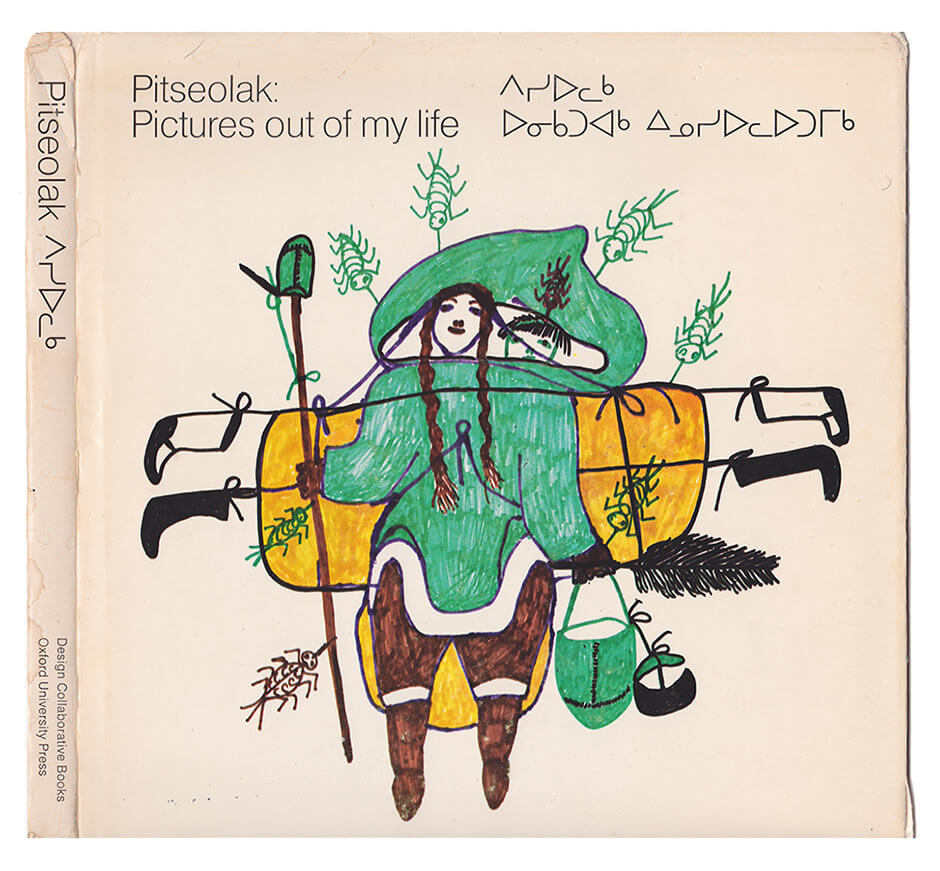

The Inuktitut transcript was revised by Ann Meekitjuk Hanson; Eber then edited the interviews into a narrative and wove in images drawn by Pitseolak during their sessions as well as selections of her best-known work to date. Pictures Out of My Life was published in both English and Inuktitut syllabics—a remarkable achievement, and a first for a publisher like Design Collaborative Books, working in conjunction with Oxford University Press. The book was a popular and critical success when it was launched in Montreal, Ottawa, and Toronto in October 1971. Pitseolak travelled south for events in these cities, and media coverage was extensive.

To date, Pictures Out of My Life remains the primary resource on the artist. It also provides personal insight into Inuit culture rather than the predominant anthropological perspective. Importantly, as one of the first autobiographical works from an Inuit artist, Pictures Out of My Life countered perceptions of Inuit as lacking in individuality and Inuit culture as being homogeneous.

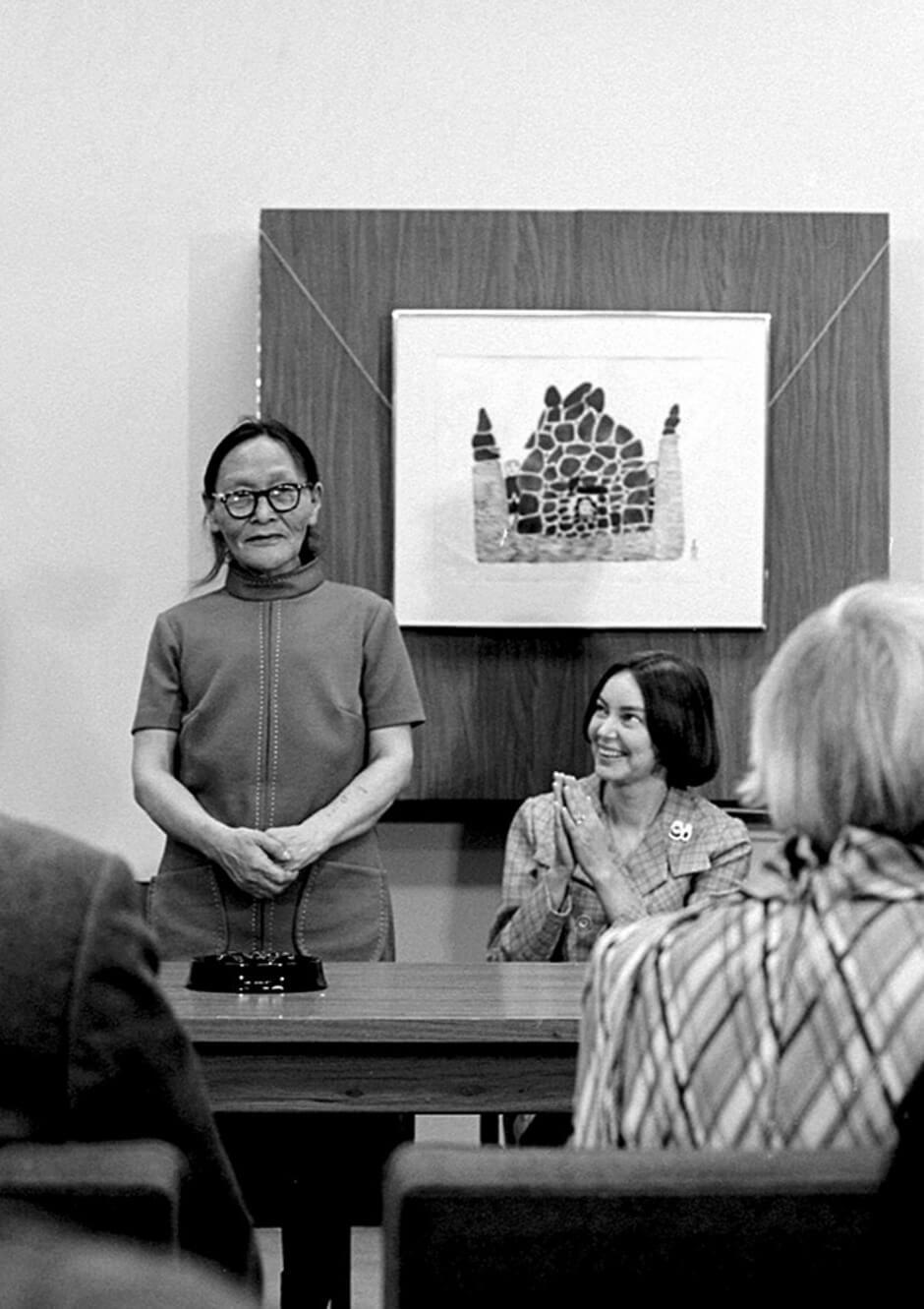

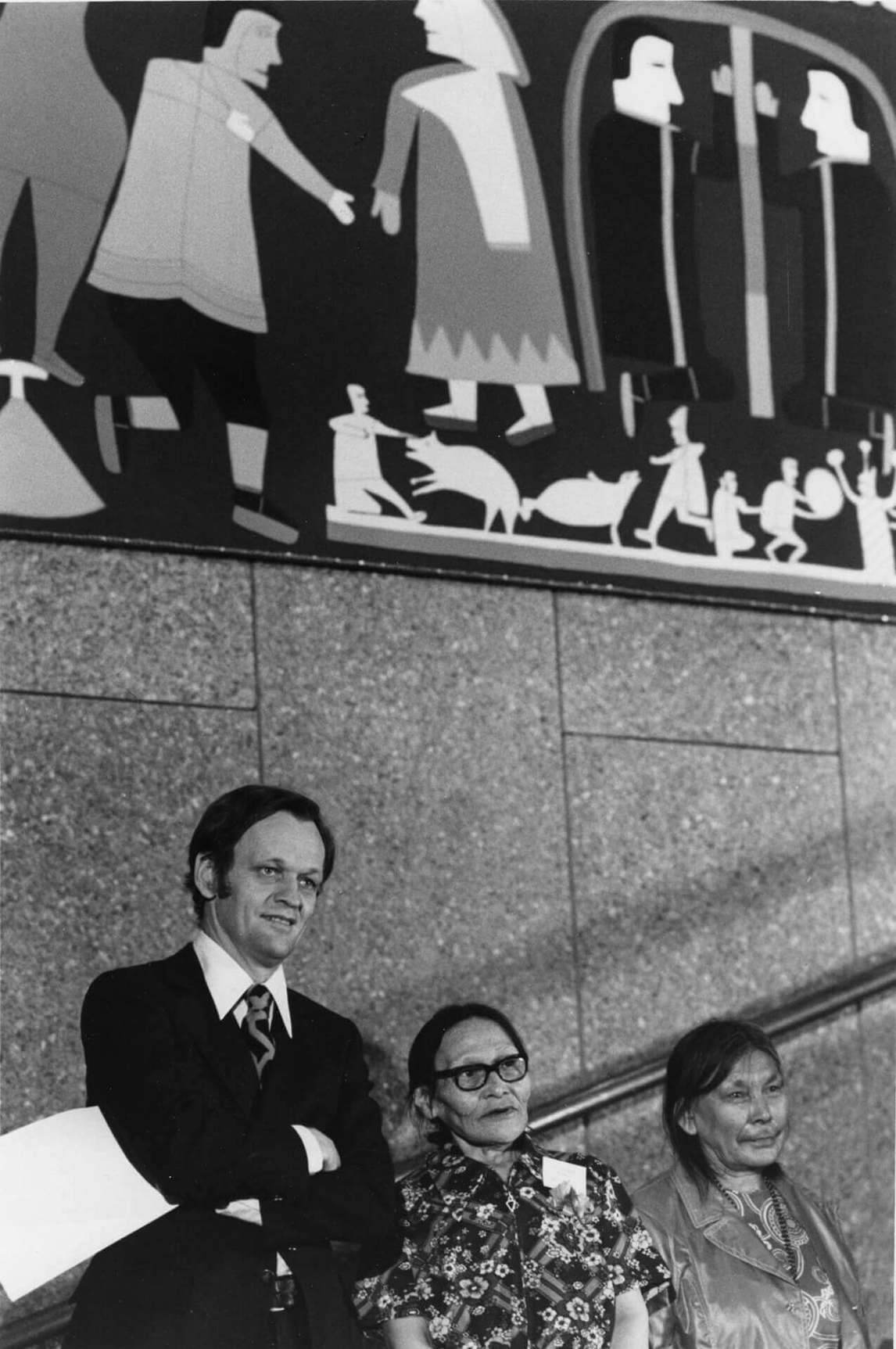

The National Film Board of Canada made a film adaptation of Pictures Out of My Life. It premiered at the National Arts Centre in Ottawa on May 12, 1973, at the same time as the unveiling of an untitled wall-hanging by Jessie Oonark (1906–1985), a contemporary of Pitseolak’s from Baker Lake. Jean Chrétien, then minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, opened the event with a speech; both Pitseolak and Jessie Oonark were in attendance.

In 1974 Pitseolak was inducted into the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts. Within two years, a retrospective exhibition was organized by the Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development, in partnership with the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative. Simply titled Pitseolak, the exhibition included one hundred drawings dating from 1962 to 1974, the later ones made specifically for the show. It toured to three venues in Canada and then the Smithsonian Institution coordinated a tour to five venues in the United States that lasted until the summer of 1977. Also in 1977, Pitseolak received the Order of Canada for her contribution to Canadian visual arts and heritage.

This period of international attention and accolades was matched by an artistic flourishing that is reflected in the most exuberant drawings of Pitseolak’s career. Over the next years, even as health concerns arose, she continued to work, providing a stable income for her extended family. After a brief illness, she died in Cape Dorset on May 28, 1983.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements