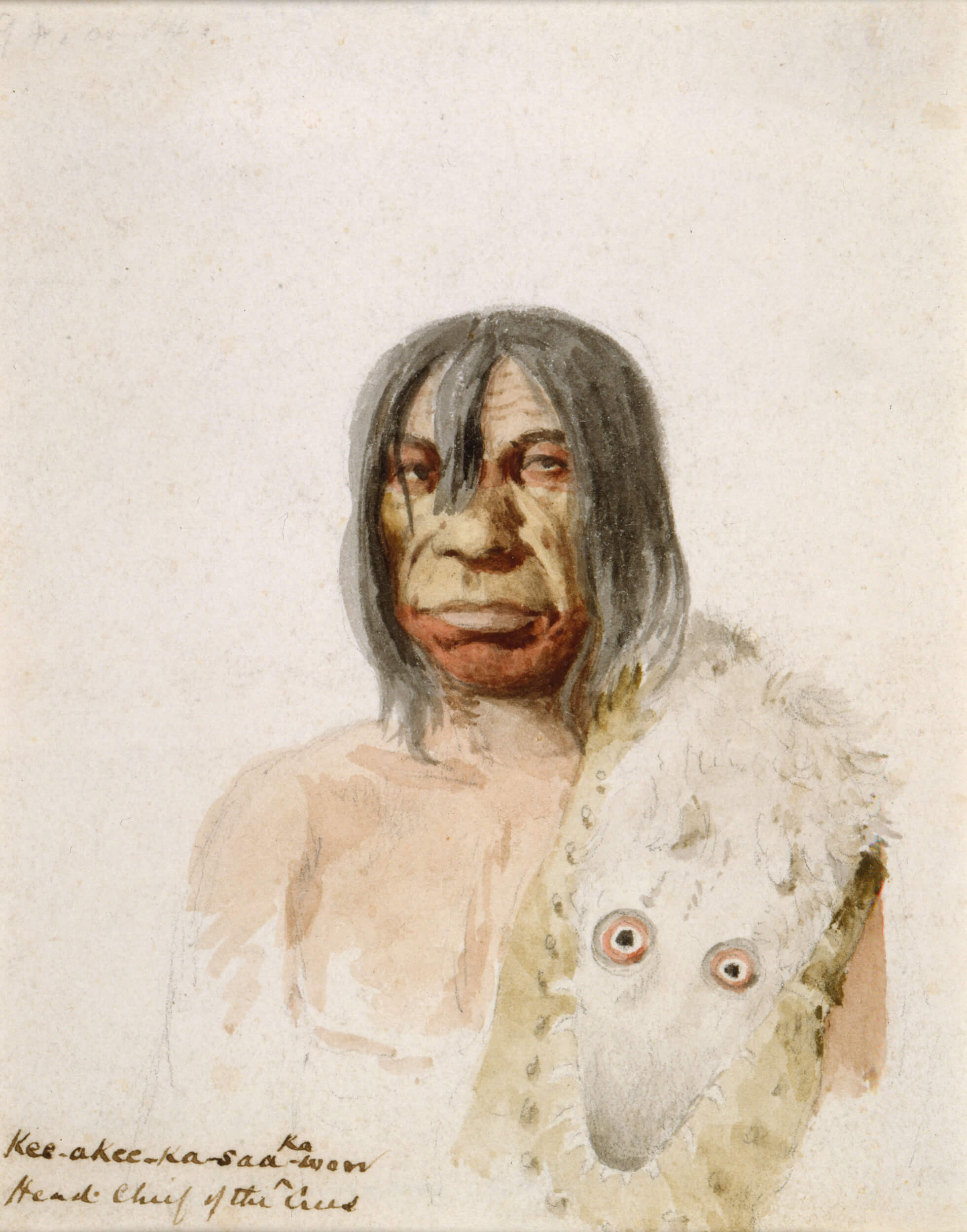

Kee-akee-ka-saa-ka-wow 1846

Paul Kane, Kee-akee-ka-saa-ka-wow, “The Man That Gives the War Whoop,” Plains Cree, Fort Pitt, 1846

Watercolour and graphite on wove paper, 13.5 x 11 cm

Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa

In his field journal Kane records his encounter with the Cree chief Kee-akee-ka-saa-ka-wow on July 14, 1846, and elaborates that he “is the man that always speekes [speaks], the last” and he “dilliveres [delivers] his ordere in a low tone in his hert [heart].” This watercolour appears to have been executed fairly rapidly, with the chief’s chest and right arm brushed in with a few broad strokes. Kane focuses on the face, noting its variations in structure: the pronounced mouth area, the heavier lower lip, the slack skin of the cheeks as they start sliding into jowls, the lined forehead. Kee-akee-ka-saa-ka-wow’s lower jaw and his shifted glance are visually reinforced by red facial paint.

The comparison between Kane’s watercolour Kee-akee-ka-saa-ka-wow, “The Man That Gives the War Whoop” and his later oil painting of the same subject is one of the most oft-cited examples of the extent to which Kane modified the essence of a sitter.

In painting the oil, Kane transforms his subject into a man whose expression has been neutralized through elongation and even idealization of the features. Kee-akee-ka-saa-ka-wow, now set against a backdrop of a foreboding sky, looks beyond the viewer. All the accoutrements, all the markers of “Indianness”—the pipe stem, the fringed shirt, the roach headdress—are marshalled to communicate the gravitas that the original watercolour evokes through physiognomy alone.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements