Paul Kane (1810–1871) was a largely self-taught artist known for his paintings of Aboriginal peoples and landscapes, which were based on sketches he made during his travels to the West. Kane produced hundreds of sketches and created a cycle of one hundred paintings that together reveal the vitality of Aboriginal culture and are of great significance today in the study of Canada’s Aboriginal and settler cultures.

Formative Years

Paul Kane was born on September 3, 1810, in Mallow, County Cork, Ireland, the sixth of eight children (four boys, four girls) of Michael Kane (1776–1851) and Frances Loach (1777–1837). Kane was about ten years old when, along with his parents and several siblings, he immigrated to Canada, where they settled in York (Toronto) around 1819. Michael Kane, originally a soldier in the British army, made his living in Canada as a liquor merchant.

Paul Kane’s talent for drawing showed itself early, and as a young adult he may have been mentored by Thomas Drury, the drawing master at Upper Canada College during 1830–33. But by that time Kane was already employed as a commercial artist, first as a furniture decorator (at Wilson S. Conger’s factory) and then in 1833 as a “coach, sign, and house-painter.” Throughout this period he continued to pursue fine art. In 1834, as an associate of the Society of Artists and Amateurs of Toronto, the first “official” art society in Canada, he exhibited nine works, mostly landscapes. Only two of these were originals; the rest were copies (including a copy of a work by Drury).

In 1834 Kane moved to Cobourg, Ontario, one hundred kilometres east of Toronto. Kane may have worked for furniture maker F.S. Clench, whose daughter Harriet Clench (1823–1892) he would marry in 1853. In Cobourg he also developed his skills as a portraitist, perhaps making connections through Wilson Conger, his former employer, who had resided there since 1829 and had become involved in municipal affairs. Kane painted the local citizenry, including members of the Clench family.

European Grand Tour

For many artists of Kane’s generation, it was de rigueur to make a pilgrimage to Italy, and especially to Rome, to study the great masterworks. Kane planned to travel with two American friends, James Bowman (1793–1842) and Samuel Bell Waugh (1814–1885), artists who had also exhibited in Toronto in 1834. In 1836 Kane left Cobourg and met up with Bowman in Detroit, but Bowman’s recent marriage dashed the artists’ immediate plans to travel to Italy.

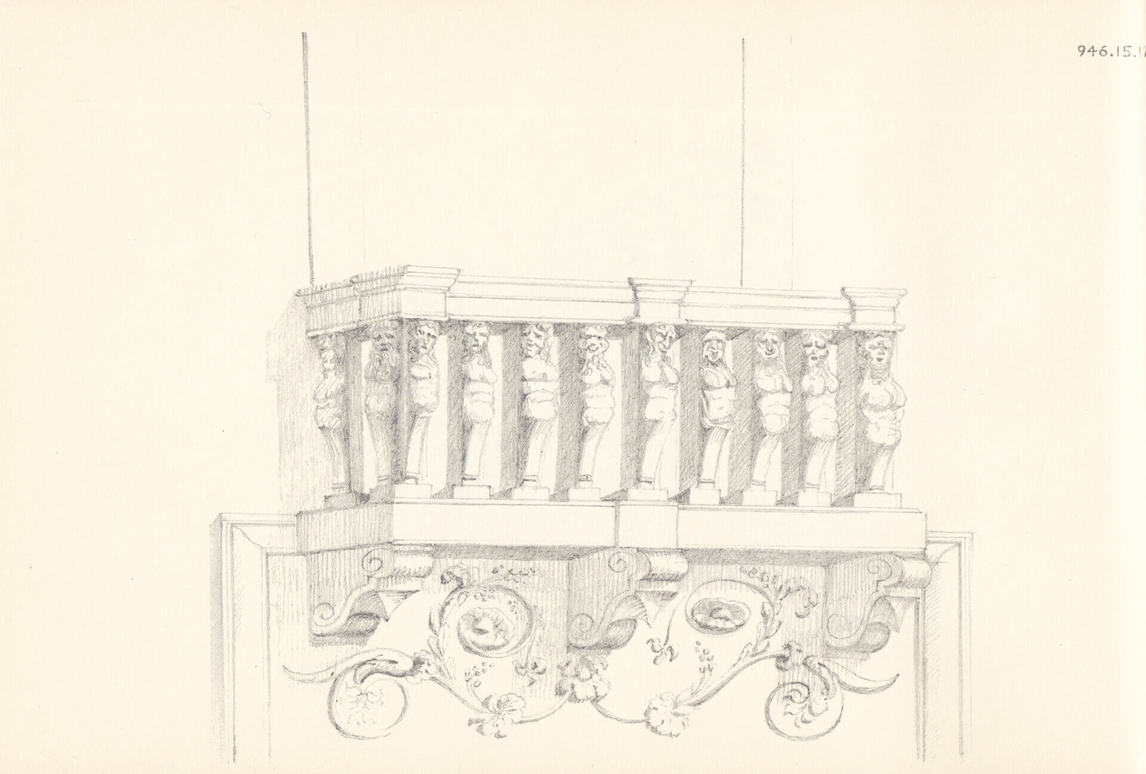

On the advice of his father, Kane remained in North America; he travelled and painted his way through the midwestern and southern United States—Detroit, St. Louis, Mobile, and New Orleans—for the next five years. Finally, in June 1841, Kane sailed for Europe, arriving three months later in Marseilles, France. He headed for Italy immediately; his sketchbooks and passport reveal he spent time in Genoa, Venice, Florence, and Rome. Kane’s spirit of adventure inspired him to hike from Rome to Naples. On leaving Italy he also hiked through the Brenner Pass to Switzerland and then travelled to France, passing through Paris on his way to London. Kane’s sketchbooks from this period show a range of subject matter—figures, furniture, sculpture, architecture—but his copies of portraits (from the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, for example) indicate that portraiture was Kane’s main pursuit.

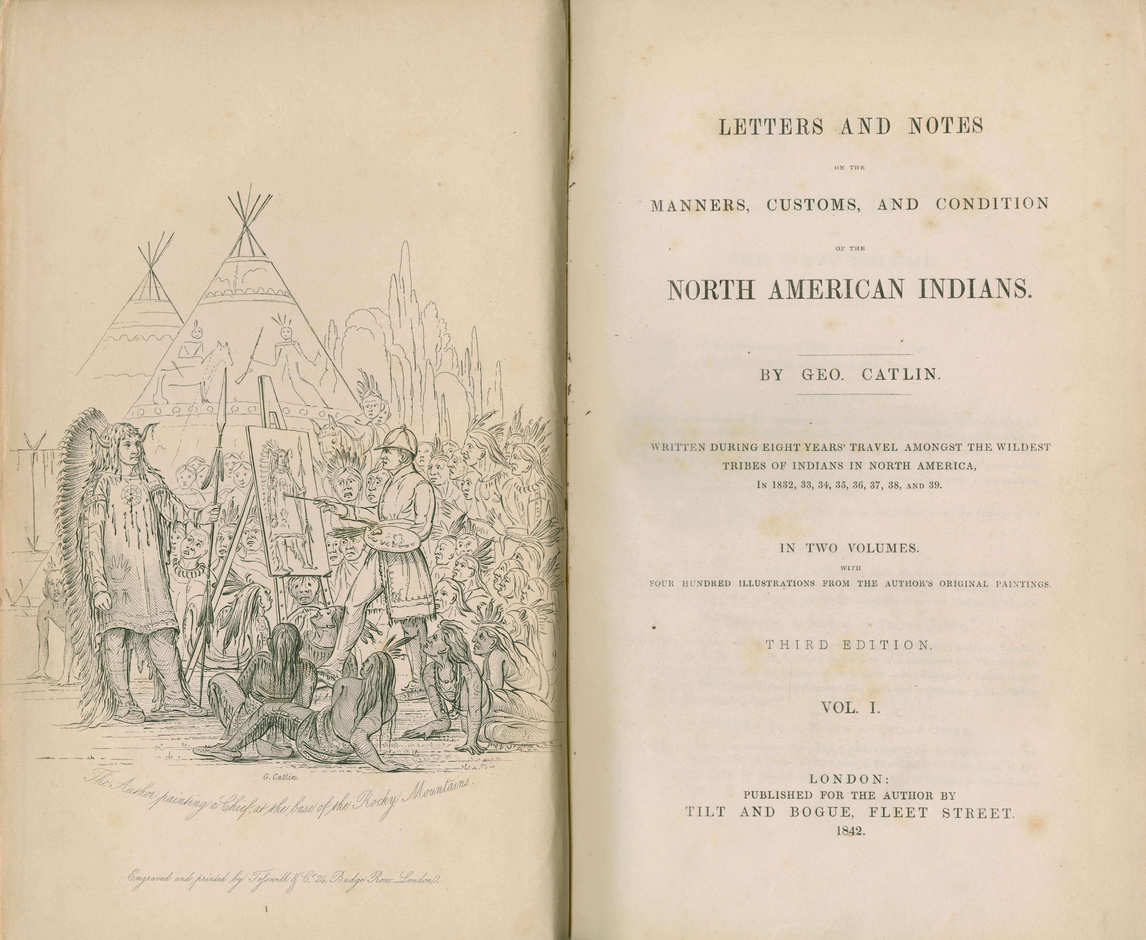

Despite his study of the masterpieces of Italy and France, it was in London that the stage was set for the ultimate direction of Kane’s career. Arriving in late October 1842, Kane may have met the American artist George Catlin (1796–1872) and probably viewed Catlin’s Indian Gallery, a showcase of paintings, lectures, and theatrical performances based on the artist’s documentation of the Aboriginal peoples of the western United States. Undoubtedly Kane leafed through Catlin’s illustrated publication Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Condition of the North American Indian. Inspired by Catlin’s experiences and his project to “salvage” Aboriginal culture, Kane would soon redirect his own artistic focus.

By early April 1843 Kane was back in the United States where he remained for the next two years, raising money to pay off debts and possibly to pay for a trip to the Northwest. In 1845 he returned to Toronto. Itinerant for almost nine years, Kane had barely set foot at home when, in June, he embarked upon his life project: to create a cycle of large studio paintings documenting the Aboriginal peoples and the

landscape of Canada’s West.

The Northwest Beckons

In embracing his own “salvage” project, Kane was very much in line with the Victorian imperialist belief that North American Aboriginal peoples were all but certain to vanish, threatened by settler contact and encroachment. His first trip, from mid-June to late November 1845, was cut short. He had naively expected that he could travel anywhere without getting permission from the authorities.

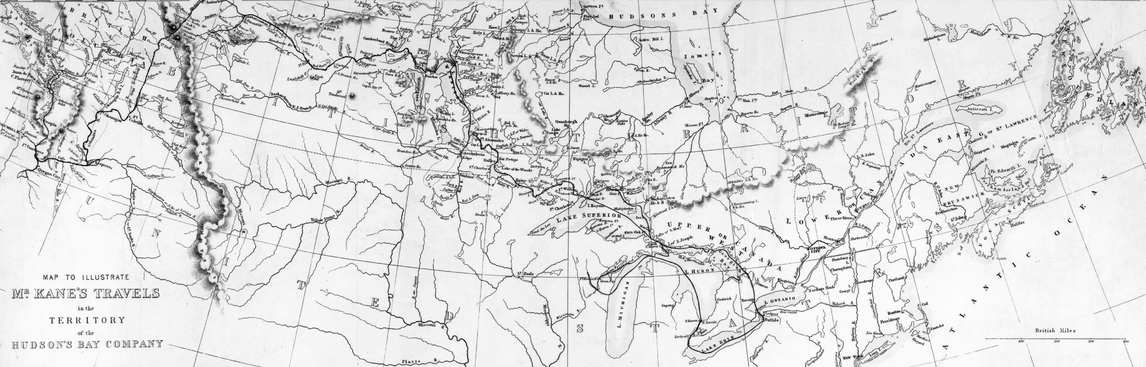

Kane had travelled and sketched unimpeded through Saugeen territory (on Lake Huron), Georgian Bay, and Manitoulin Island, but at Sault Ste. Marie, as he was poised to enter Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) territory, he was informed by HBC’s local chief trader, John Ballenden, that to travel farther would be dangerous without the support of the company’s governor, Sir George Simpson. Kane had to complete this particular venture in the Fox River region of the Wisconsin Territory. However, over the winter in Toronto, he began negotiating with Simpson for permission to travel in the Northwest. Ballenden wrote letters to Simpson on Kane’s behalf, as did the scientist and colonial administrator John Henry Lefroy, both of whom were familiar with Kane’s artwork.

HBC’s approval was critical for Kane’s project: it not only granted authorization but also facilitated his next trek. Beginning in late May 1846, he travelled by canoe, York boat, horse, and on foot across prairies, the subarctic, and mountains, with fur-trade brigades or with hired local guides. For over two years Kane travelled along HBC routes, venturing as far north as Fort Assiniboine and as far south as Fort Vancouver in the Oregon Territory, exploring that vicinity and northward on Vancouver Island.

Throughout the trip he encountered the Aboriginal and Metis people who were integral to the success of HBC’s commercial endeavours; he took their “likenesses” (in nineteenth-century parlance) as well as sketched their daily life, customs, and cultural artifacts, and the landscape. He sporadically recorded his experiences in a journal and generated hundreds of sketches and studies in pencil, watercolour, and oil. Most of these works were created as he travelled or during periods of residence at HBC posts, but some likely were completed back in Toronto. All of this work was the primary material for his planned cycle of oil paintings to illustrate the life of “the North American Indian.” By the time Kane returned to Toronto in October 1848, he had travelled many thousands of miles.

The Cycle Takes Shape

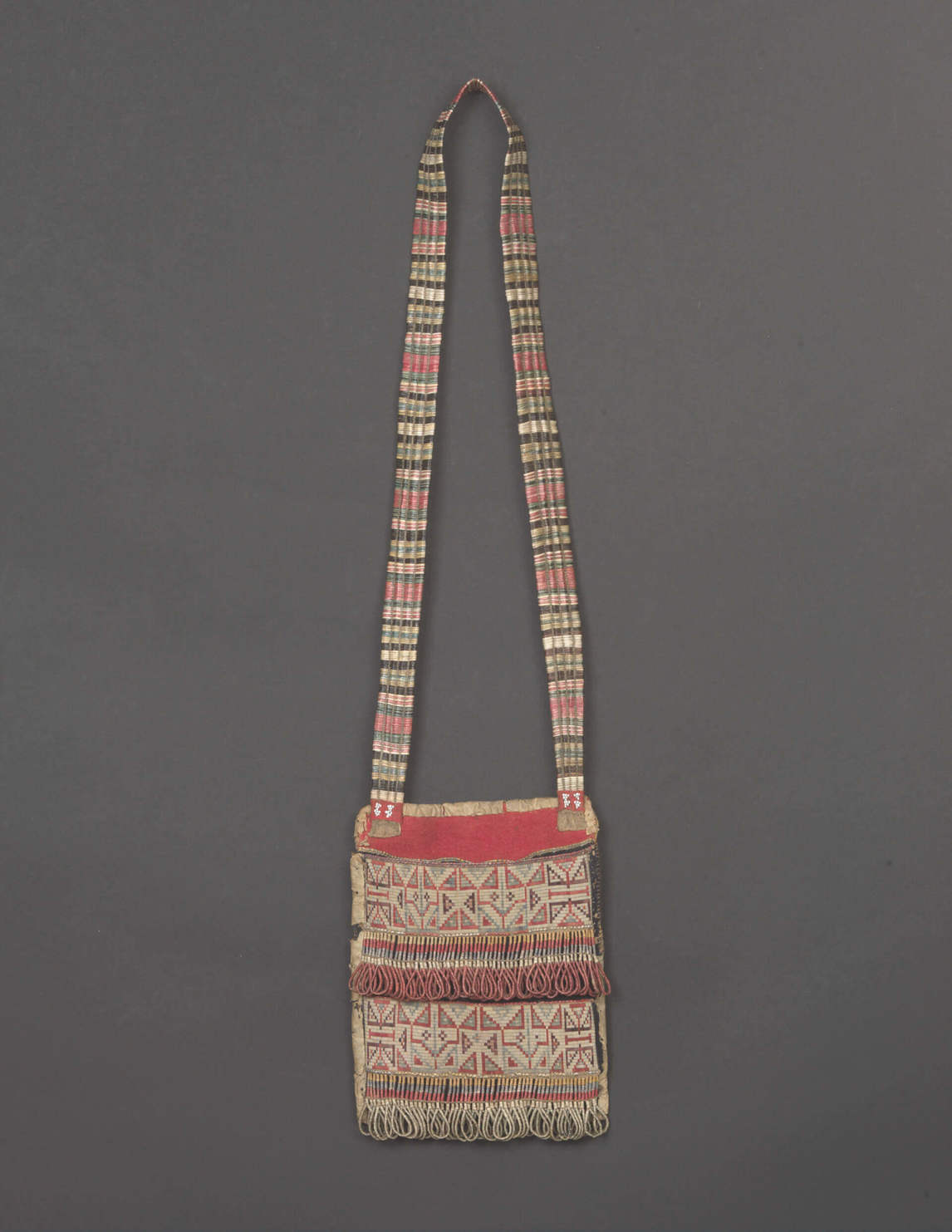

For the next decade Kane was devoted to producing his cycle of one hundred paintings, along with an illustrated account of his travels in the Northwest. He lost no time in promoting his western adventures and artistic labours: within a month of his return in 1848, and with the help of Harriet Clench, Kane organized 240 “sketches of Indians, and Indian Chiefs, Landscapes, Dances, Costumes, &c. &c.” for an exhibit held at Toronto City Hall. Included were a number of Aboriginal artifacts acquired by Kane. In the years following his travels he exhibited at various provincial exhibitions in Upper Canada, showing paintings in the years 1850 to 1857; presented papers at the Canadian Institute (he was a founding member), which were also published in the institute’s journals; and received visitors in both home and studio, regaling them with stories of his experiences while showing his sketches and oil paintings. According to one guest who visited in October 1853, Kane’s “great ambition” was to “make a perfect collection illustrative of Indian life and to exhibit it in England.”

In 1851 Kane petitioned the Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada for financial support to execute his grand program of painting; he received just £500 in advance for only twelve prospective oils. His saviour came in the form of George William Allan, a lawyer and municipal politician who, with a substantial inheritance in 1853, became “one of Toronto’s most prominent citizens”—and Kane’s patron.

Allan paid the artist $20,000 for one hundred paintings, and the entire lot was delivered to Moss Park, Allan’s Toronto mansion, in 1856. Also delivered in 1856 were the twelve paintings commissioned by the Canadian government in 1851—all of which were versions of paintings in Allan’s cycle of one hundred.

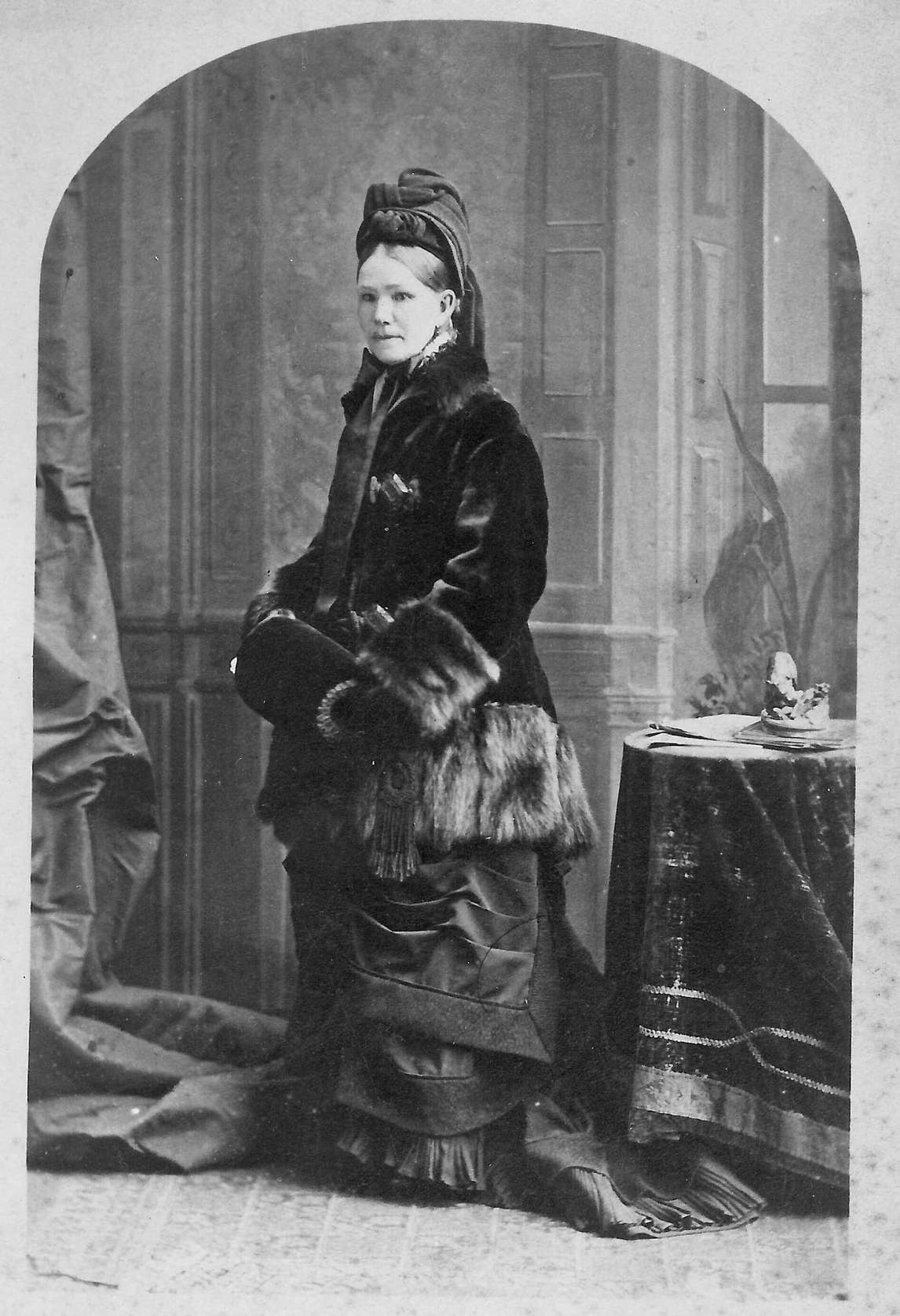

In many of his endeavours Kane was likely aided by Harriet Clench, whom he married in 1853; she was financially secure and an artist herself. In 1848, two years after receiving artistic instruction at the Burlington Ladies’ Academy in Hamilton, she became an assistant instructor in drawing and painting at the same school, and in 1849 she exhibited at the Provincial Exhibition held in Kingston. The Kanes and their four children lived in a house at 56 Wellesley Street East, built the same year they married. The house, which Kane enlarged over time, is still there, a historic site.

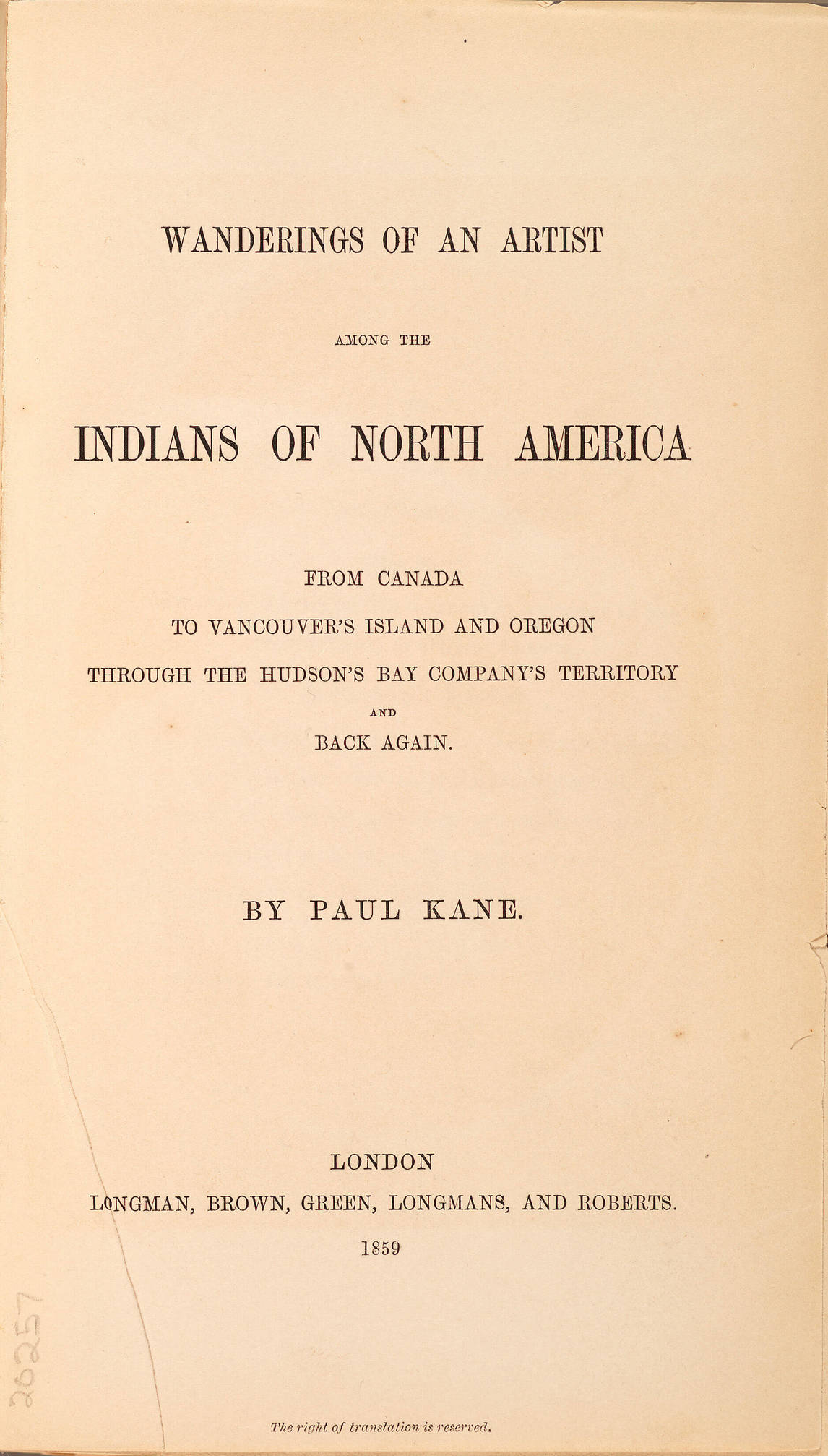

A ghostwritten account of Kane’s travels based on the artist’s journal was published in London in 1859 and dedicated to George W. Allan. Unfortunately, Wanderings of an Artist among the Indians of North America, from Canada to Vancouver’s Island and Oregon through the Hudson’s Bay Company’s Territory and Back Again was not the grand production that Kane anticipated. He went to London to promote the project and to oversee the lithography of his paintings, but out of his one hundred oil paintings, the book featured only eight chromolithographs and thirteen woodcuts as illustrations. Also, while the book’s translation into French, German, and Danish suggests its popularity in the European market, on the home front its reception was mixed. The Toronto Mechanics’ Institute—a centre for adult learning—did not acquire it for its library owing to the apparently prohibitive six-dollar price tag, and one unidentified member of the institute, in a letter to the editor of the Globe, referred disparagingly to Wanderings of an Artist as “twaddle.”

Kane’s artistic output appears to have been curtailed after the publication of Wanderings of an Artist. While he retained a studio on King Street East until 1864 and continued to be identified in the Toronto city directory as an artist, his career had plateaued, with little further production. It is believed that Kane’s eyesight had started to fail, and there is mention of his having injured his spine in a fall in 1870. He died in Toronto on February 20, 1871, of a “liver complaint,” which has led to speculation that Kane suffered from alcoholism, but this has not been confirmed. He is buried in St. James Cemetery in Toronto.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements