Paul-Émile Borduas created ever more radical and focused work. His artistic development is reflected in well-defined periods.

Representational Period

Borduas’s early work reflects his apprenticeship with the Quebec painter Ozias Leduc (1864–1955) and his academic training at the École des beaux-arts in Montreal in the 1920s. He had hoped to follow in Leduc’s footsteps and become a church decorator: for this reason, in his youth Borduas never strayed from what the churches would accept in Quebec. During his first trip to Paris, where he studied at the Ateliers d’art sacré, Borduas began to explore the work of Paul Cézanne (1839–1906), Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919), and Paul Gauguin (1848–1903). His representational work from the late 1930s to the early 1940s reflects these early influences.

The Automatiste Period

In 1937 Borduas was hired to teach drawing and decoration at the École du meuble in Montreal. It was here, in the school’s intellectually stimulating atmosphere, that Borduas discovered the work and ideas of the founder of Surrealism in France, the poet André Breton, above all through reading “Le château étoilé” in the journal Minotaure.

In “Le château étoilé,” Borduas read Breton’s description of a lesson that Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) gave his students; this would have a profound influence on the development of Borduas’s art:

The lesson Leonardo gave his pupils, in which he encouraged them to base their pictures on what they could see “painted”—remarkably coherent and personal for each of them—on an old wall after having contemplated it for some time, is still far from understood. The whole problem of the transition from subjectivity to objectivity is implicitly resolved here, and the significance of this resolution is much greater in terms of human interest than the significance of a technique, even when that technique is one of inspiration itself.

Gazing at the cracks in an old wall or reading the shapes of clouds and reproducing them in a painting may not appear to be practical endeavours for an artist. But da Vinci—through the prism of Breton—certainly seems to suggest that an artist can be without a preconceived idea before launching into a work. Inspiration for a work of art can come from somewhere unconnected to the artist’s meditations or training, not to mention the iconographic styles and conventions of the time.

In 1941 Borduas began a series of gouaches, applying da Vinci’s advice. In a conversation with the art historian and critic Maurice Gagnon, Borduas shared the following revelations about his experiments with automatism, which Gagnon had the good sense to jot down:

I begin with no preconceived idea. Faced with the white sheet, my mind free of any literary ideas, I respond to my first impulse. If I feel like placing my charcoal in the middle of the page, or to one side, I do so with no questions asked, and then go on from there. Once the first line is drawn, the page has been divided and that division starts a whole series of thoughts which proceed automatically. When I use the word “thoughts” I mean painterly thoughts: thoughts about movement, rhythm, volume and light, not literary ideas. Literary ideas are only useful if they are transformed plastically.

Transferring this approach to the medium of oil posed specific problems owing to the longer drying time for oil compared with that for gouache, a water-based medium. Borduas ended up working in two stages, first painting the ground and then the “objects” suspended in front of that ground, which recedes into infinity. In the gouaches he produced using the new approach, he perhaps unconsciously evokes the composition of a still life or portrait; the oil paintings he made from 1943 onward are reminiscent of the landscape formula.

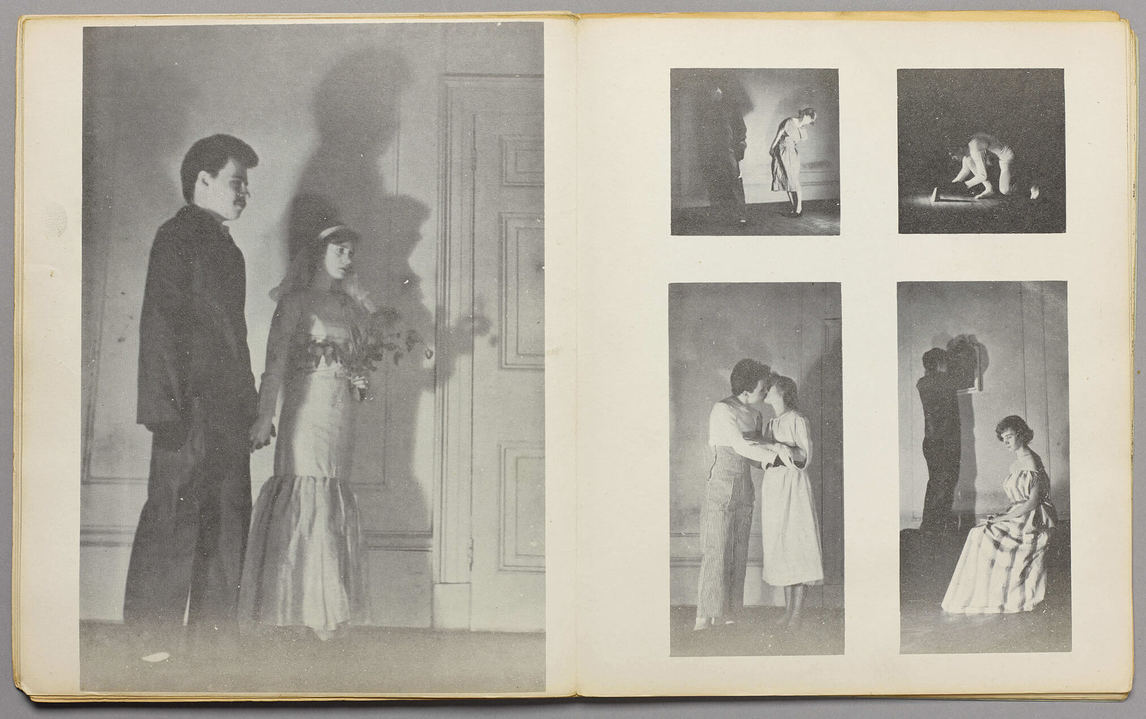

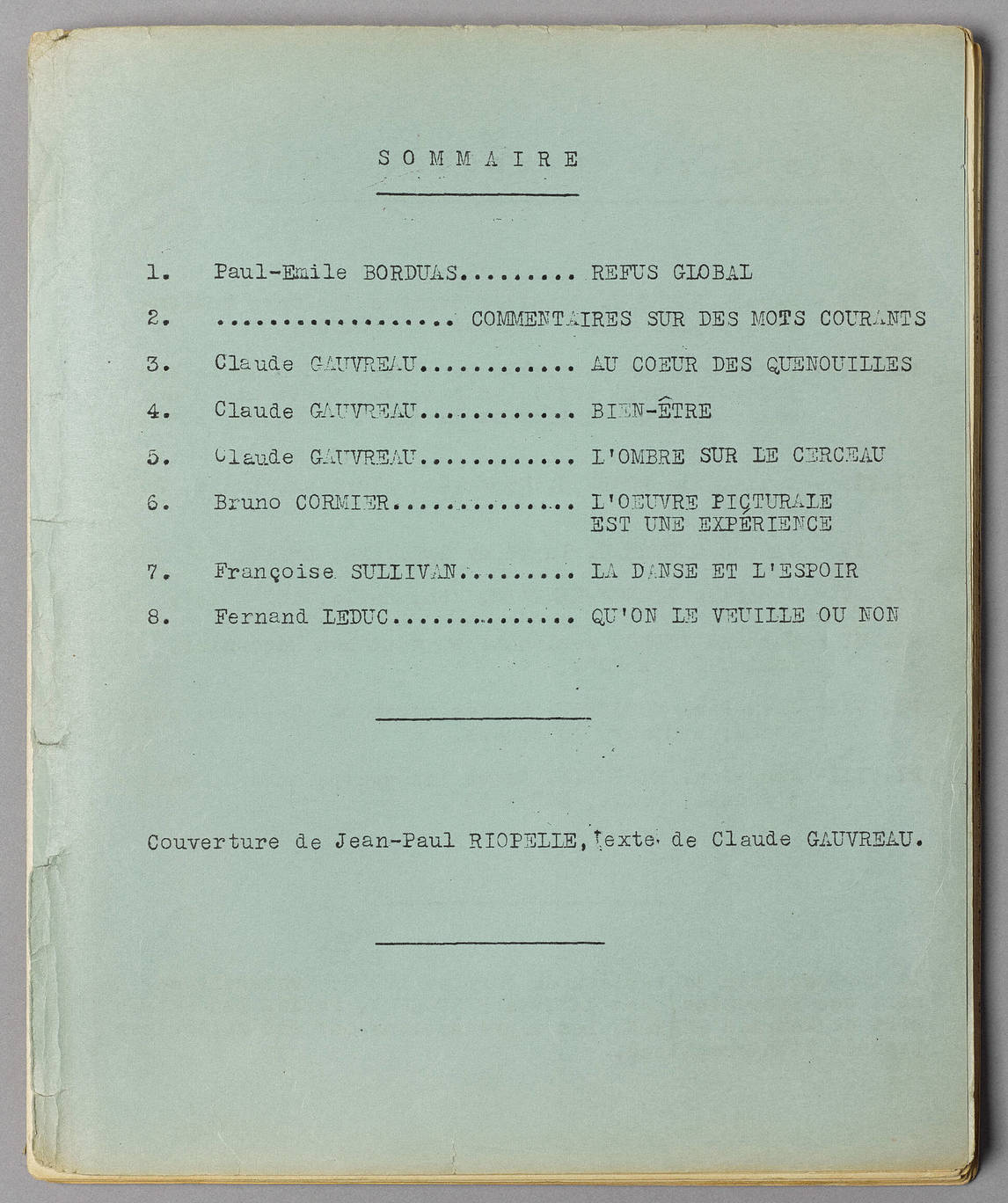

During this time, Borduas had begun to dissociate himself from his contemporaries and draw closer to a group of artists of the younger generation, including some of his students at the École du meuble. Some were members of the Automatistes, a group led by Borduas that can be dated to 1941, when they began meeting at his studio on Mentana Street. The Automatistes held two exhibitions, in 1946 and 1947; Leeward of the Island or 1.47, 1947, was shown at the second of these. Borduas’s activity as an Automatiste culminated in the release of the Refus global manifesto in 1948. The Quebec government’s condemnation of the manifesto contributed to his decision to leave the country five years later.

New York Period

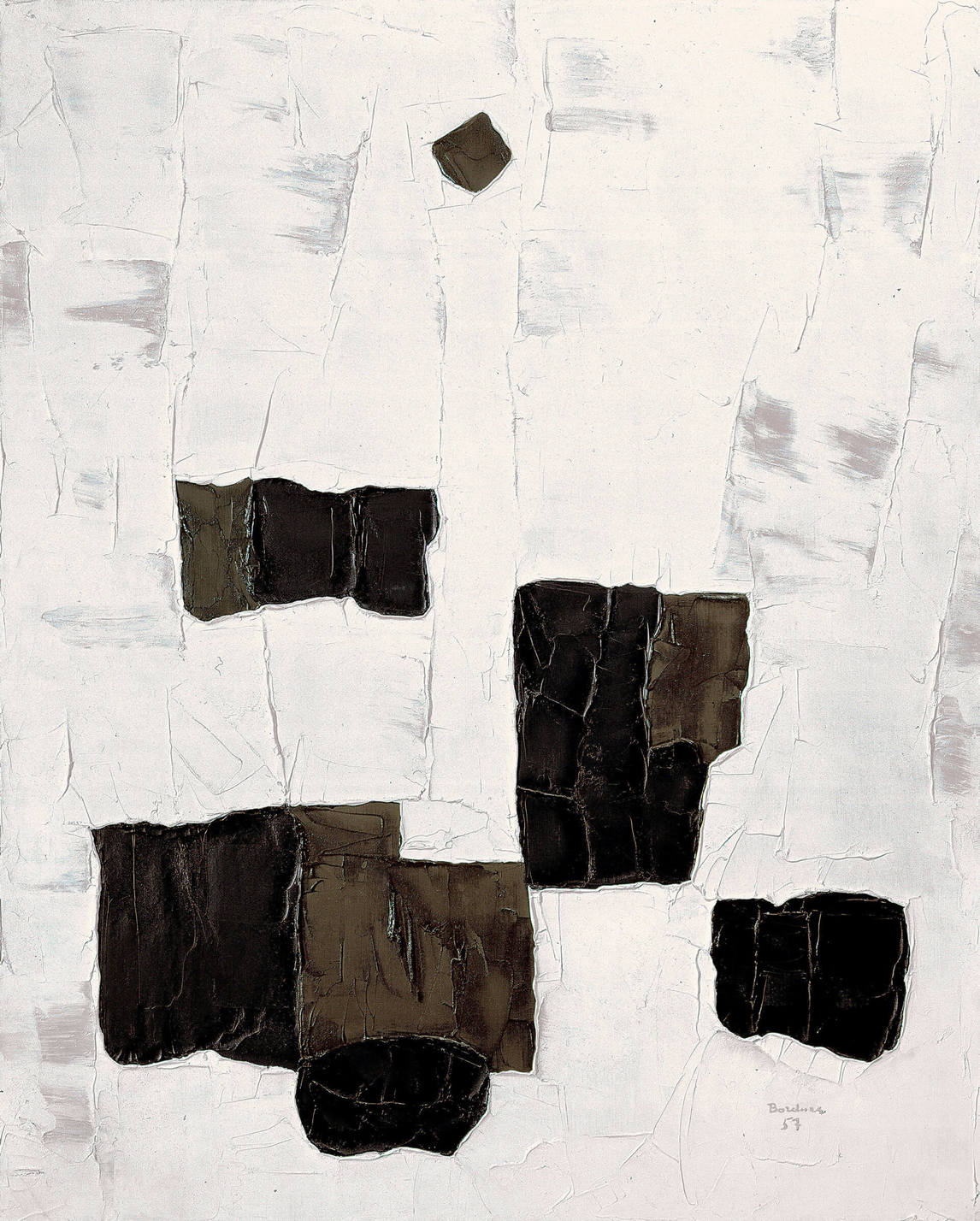

Borduas’s later work—especially his paintings from 1951 and 1952 and those he created in Provincetown, Massachusetts, just before settling in New York—reveals that he was moving toward a personal form of Abstract Expressionism. The “objects” in his Automatiste paintings become fragmented spots, or marks, applied with a palette knife, and tend to spread across the entire picture surface. By replacing the brush with the knife to paint the ground, he gives the work a new solidity, and above all, he brings the objects closer to the pictorial surface. The fusion of object and ground is imminent.

To say that New York painting had no influence on Borduas’s work would be an exaggeration, but some aspects had little impact on him. American painting sought to create canvases halfway between mural and easel painting—that is, between painting that, in Europe, had served to transmit political or other ideologies and painting that was personal expression. Borduas’s work reveals few traces of this kind of preoccupation, with the exception of one large canvas, Easter (Pâques), 1954.

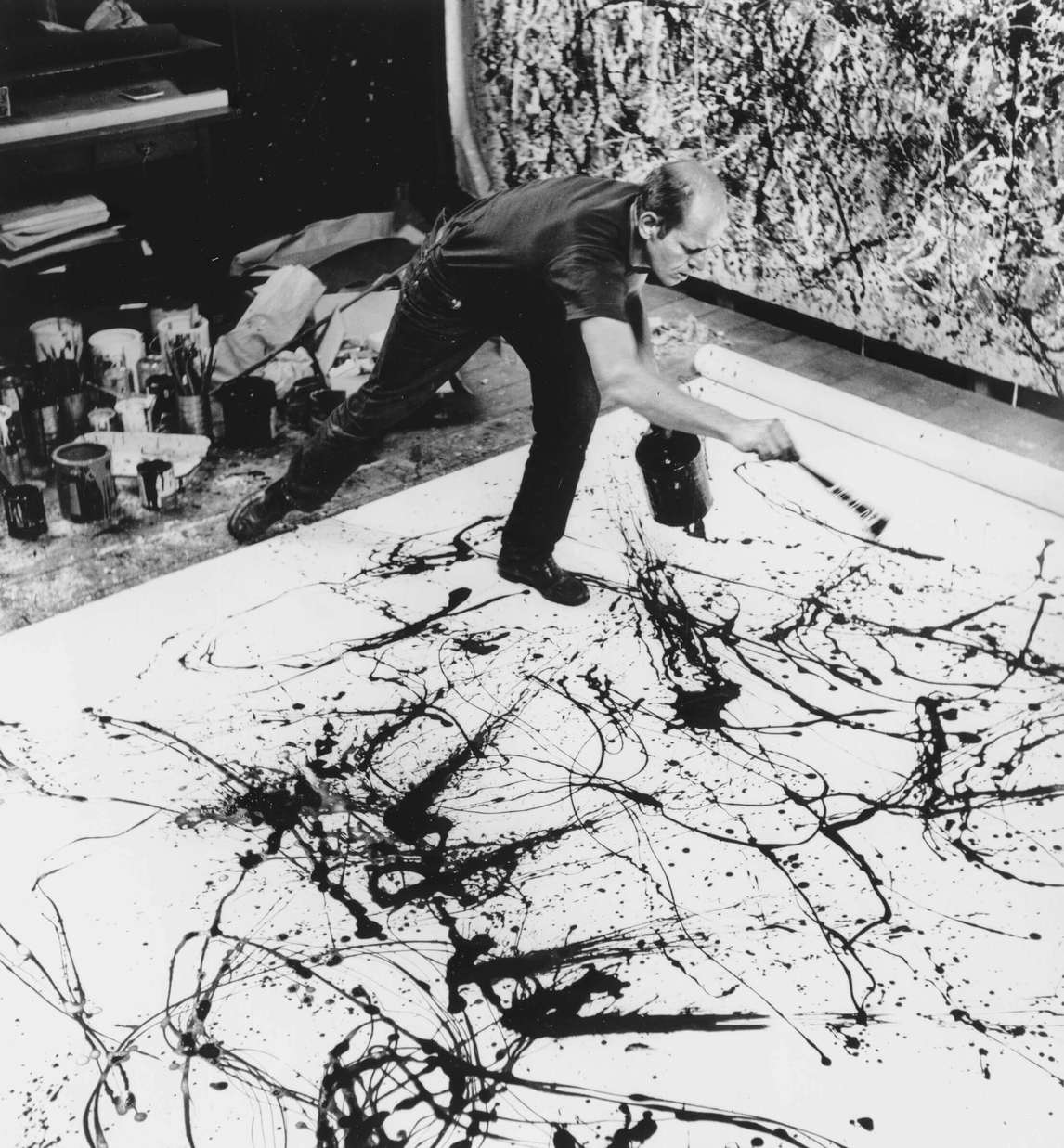

Borduas was more interested in the idea of affirming the primacy of the individual and the complete autonomy of painting. American painters were becoming increasingly detached from what they perceived as “beautiful painting,” in the words of the critic Clement Greenberg; hence, the idea of hierarchical composition that was associated with Abstract Expressionism led them to what the same critic described as “all-over composition.” In this style of painting no one focal point takes precedence over another, and there is no hierarchy among the elements: the effects are distributed evenly across the entire surface—for example, the lines in the works of Jackson Pollock (1912–1956) or, equally, the colour-fields in works by Clyfford Still (1904–1980), Mark Rothko (1903–1970), and Barnett Newman (1905–1970). Malicious critics likened this genre of painting to wallpaper, where motifs are repeated in a uniform manner and where it could be said that any one part produced more or less the same effect as the whole.

In comparing Borduas’s Automatiste works with this American style of painting, the differences are obvious. In the former, the objects attract attention and detach themselves from the ground, which seems to recede into infinity.

There is a clear hierarchy between the object and the depth of space in which it is placed. Often Borduas attempts to illuminate the nature of the object in the title he chooses once the canvas is finished, as in Flowered Quivers or Nature’s Parachutes. Some of his titles attempt to define the ground from which the objects are detached, as in Morning Meeting or Figure at Dusk, evoking the light in the morning or at the end of the day.

Yet Borduas ultimately questions the dichotomy of object/ground in his Automatiste paintings. The object erupts; the ground penetrates the foreground; eruptions and grounds are increasingly textured and eventually fuse into a whole, not far from recalling an all-over composition. From this perspective, the canvas The Signs Take Flight, 1953, no doubt precipitated this turning point for Borduas. His painting becomes increasingly assured, evident in the rich impasto, the strong sense of movement (toward either the periphery or the centre of the composition), the dramatic contrasts in the opaque colours (with white dominating), and the delicate use of transparency. Works from Borduas’s New York period, including The Joyful Wands (Les baguettes joyeuses), 1954, became a favourite with Canadian collectors, including Toronto art dealer Blair Laing, who regularly visited Borduas in his studio in New York and later in Paris.

A Dialogue with Pollock and Kline

In his 1954 watercolours Borduas entered into a direct dialogue with American Abstract Expressionist painting—specifically, the work of Jackson Pollock. Borduas experimented with Pollock’s drip technique, though Borduas’s watercolours are small in scale compared with Pollock’s monumental canvases. Rather than dripping and spattering the paint, Borduas used the flick of the brush, at times repeated on either side of a central axis. This is the only discernible element of control in these watercolours, which Borduas referred to as triumphs of “accident”—creating lines or marks of variable thickness in red, black, brown, and ochre, veritable splashes. Drip painting did not have a marked influence on Borduas’s work in oil, but several of his watercolours are true homages to Pollock’s immense talent.

It is unclear, however, whether Borduas fully understood Pollock’s drip technique. He speaks of it as an “accident” multiplied ad infinitum: “For instance, the smallest accident in a painting by Pollock has the reality, and unpredictability in the universe, of a grain of sand or a mountain—and yet, without our knowing how, delivers the emotive quality of its author.” This notion of accident, borrowed from the Surrealists, is a poor description of Pollock’s method, because it assumes that the artist has no control over the process and that where the paint falls is by chance.

So how did Pollock proceed? He began by placing his canvas on the floor, giving him a view from above. He allowed paint in a tin to drip from a stick or a dry brush. By varying his movement, at times truly dancing around the surface, Pollock was able not only to invest the lines with a unique energy—the critic B.H. Friedman would speak of “energy made visible”—but also to maintain their even distribution across the entire surface to achieve an all-over composition. Thus there does exist an important element of control, to which the notion of accident does not do justice.

Borduas uses Pollock’s drip technique in his oil painting Graffiti, 1954, but the technique as used by Borduas does not have the structuring function it does in Pollock’s paintings.

The black and white paintings of Franz Kline (1910–1962) would have a greater impact on Borduas’s later development, including his Paris period. Eagle with White Family (L’aigle à la blanche famille), from 1954, is characteristic in this regard. The eagle spreads its black wings in a V-shape, sending the black and coloured spots of its “white family” to the periphery, as it does to the red and green spots in the white space. Borduas shifts from using a very diluted wash to using solid, clear brush strokes. Spots escape here and there from the tree-like elements, enriching the invariably white ground in places. Although the reference to Kline is less obvious than the influence of Pollock’s drip technique on his 1950s watercolours, Borduas more easily integrates Kline’s grand propositions with his own universe.

Paris and the Black and Whites

Borduas left for Paris in 1955, just as he was achieving some success and recognition in New York. In Paris his painting developed in a direction that was unique, though not in tune with the dominant currents in the city at that time. Neither the Lyrical Abstraction nor the geometry of the French disciples of the Dutch painter Piet Mondrian (1872–1944)—nor indeed the neo-figurative, from Jean Dubuffet (1901–1985) to the New Realists—corresponds to Borduas’s evolution.

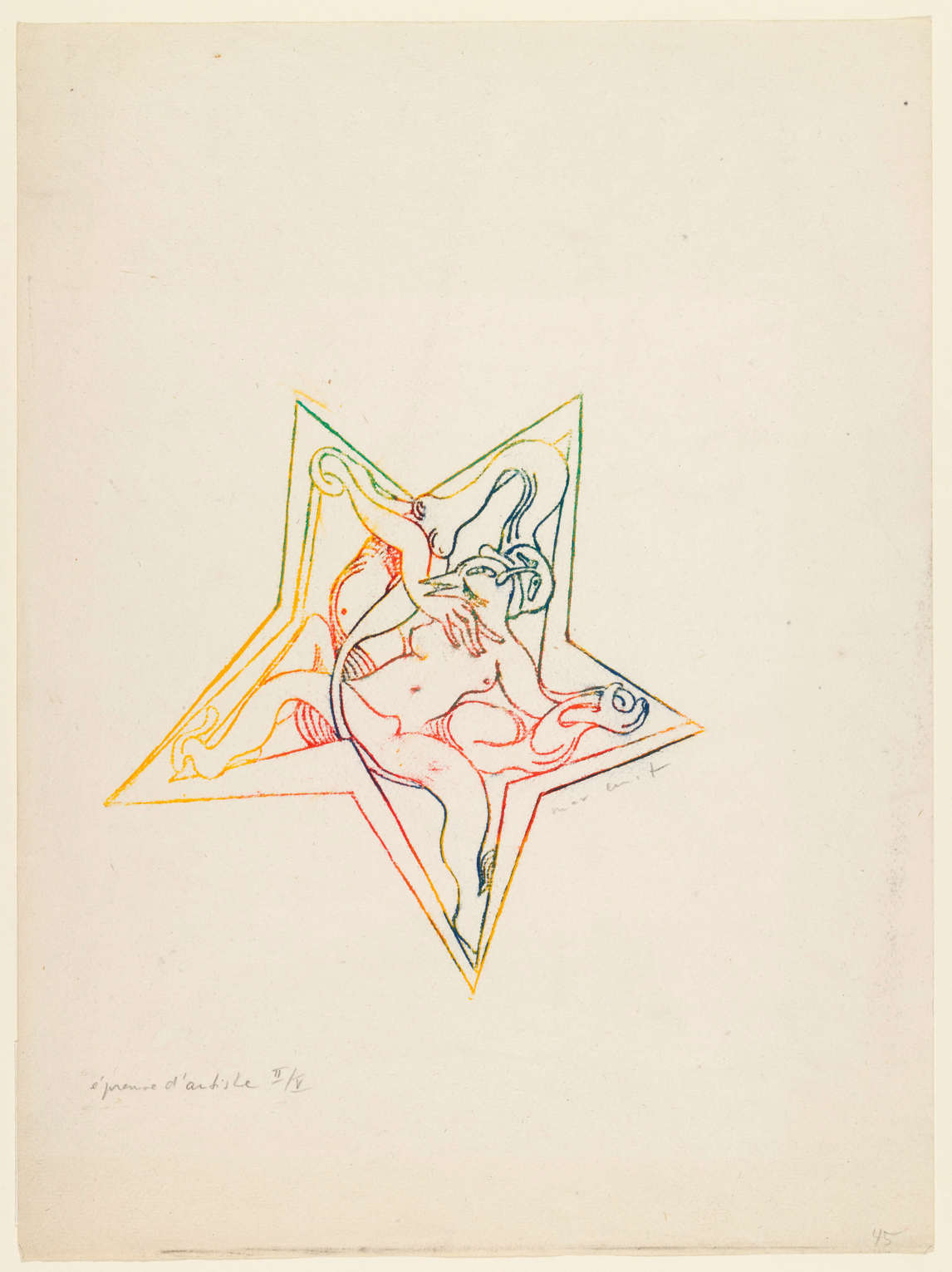

In Paris Borduas painted his famous Black and White series, which included Radiating Expansion, 1956. The creation of this series corresponds both to his desire to clarify his ideas and to his unfailing propensity to explore new directions. Suddenly black spots appear in his work. Are they a reaffirmation of the object in the form of absence? Or are they a return to the dichotomy of object on ground, but without a suggestion of depth? Borduas speaks of “cosmic paintings,” a term that, at most, could be applied to his famous painting The Black Star, 1957.

Certainly the paintings of this period express his increasing determination to move toward an “architectural construction,” which would continue to the painting Symphony on a White Checkerboard or Symphony 2, 1957. His work becomes increasingly austere and stripped, sometimes assuming a frankly calligraphic quality with bold signs on a white ground.

The paintings Borduas made in Paris served to only increase his matiériste tendency, to adopt the French expression, which relies on ever thicker impasto, allowing us to discern even the direction of the knife strokes. Paradoxically it is this material aspect that brings us closer to the presence of the painter in his canvas. To borrow from the theory of indexicality developed by American philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce, impasto is an index of the painter’s involvement in the fabrication of his canvas, in the same way that effects are an index of their cause, without there being a resemblance between the two.

Ideas and Teaching

Some artists, such as Alfred Pellan (1906–1988), believe that the painter should be solely concerned with the aesthetic choices to be made. In the Refus global manifesto, Borduas called this position taking refuge in the “barracks of plastic arts.” He believed that to create modern art the artist must take a stance on modernity on all levels—psychological, social, and political. Unsurprisingly, Borduas’s artistic practice is accompanied by the writing of a manifesto and other texts on the role of the artist.

Borduas traces his social engagement to his experience of teaching at the École du meuble in Montreal. He describes his first students when they arrived in his class:

And so I welcomed these first-year big boys, worried about the milieu in which they found themselves, cautious, withdrawn, impersonal to the extreme; embarking on the study of design with their entrenched prejudices, their already old passive habits [attitudes] imposed by force over the course of twelve or fifteen years of schooling: well-behaved, silent, inhuman. They expect precise instructions, indisputable, infallible. They are disposed toward the most complete self-denial in order to acquire a bit of skill, a few new recipes to add to a false baggage that must have been a heavy burden.

In Borduas’s analysis of his students, there is no mention of their knowledge of drawing: he speaks only of what is most relevant to him—their behaviour, their passivity, their total impersonality. Borduas knew that he could only hope to guide his students to discover their own style by addressing the root cause of their passivity.

To become a creator, all that was necessary was to learn strange mechanics by means of thankless exercises: digging through and erasing to no avail and foolishly.… It was a matter of casting off this mad hope at all costs and to hide beneath a pile of personal debris and to be determined to resolve once and for all these problems of representation, of expression. The path toward individual experimentation was laid open. The student no longer seemed to be a shapeless sack but an individual at a precise moment of his development.

Borduas’s text for the Refus global grew out of his experience with these students. He attacks two factors behind this depersonalization: the Catholic religion, with its insistence on dogma and its obsession with all things sexual; and the French-Canadian identity, as expressed in the language and traditional rural life. With no salvation outside of these two value systems, the consequence was entrapment within a kind of Quebec ghetto, along with suspicion of anything that came from outside—including the rest of Canada. (Hugh MacLennan’s novel Two Solitudes provides an accurate depiction of the French-English divide in Quebec at this time.) It was a universe of fear: “Fear of prejudice, of public opinion, of persecutions, of general disapproval; fear of being alone, without God and the society which isolate you anyway … fear of new relationships; fear of the superrational [sic]; fear of necessities; fear of the floodgates opening on one man’s faith—on the society of the future.” For many the only solution was to cave in, to conform, to follow the herd; only those who defined the culture—the clergy primarily and the politicians—came out ahead. And in the Quebec of “survival” nothing was changing. Hence the cry, midway through the manifesto: “To hell with the goupillon and the tuque. They have seized back a thousand times what once they gave.” To offer escape, the manifesto seized upon anarchy—“the resplendent anarchy”—the end of the reign of those who defined the culture.

The effect of the Refus global on French-Canadian culture was enormous. (The term Québécois was not widely used until the 1960s.) Refus global is the refusal of the old ideology of preservation (or survival), to cite the terms used by the sociologist Marcel Rioux, which defined French-Canadian identity by its language and served as a keeper of the faith, creating an unbridgeable divide between Quebec and the Anglo-Saxon Protestant majority in the rest of Canada and in the United States. Borduas wanted to break with the idea that only a return to the soil—the affirmation of the peasant roots of French Canadians, or what those roots were believed to be—would assure the purity of the French-Canadian identity threatened by the pluralism of urban life. It was time to catch up with the evolution in thought around the world and to open themselves not only to the art being made elsewhere—Borduas was thinking above all of Paris—but also to progressive ideas: “Make way for magic! Make way for objective mysteries! Make way for love! Make way for necessities!”

The Refus global manifesto was released on August 9, 1948, with the main text written by Borduas; it was countersigned by fifteen members of the Automatistes. Needless to say its release had a profound impact over the course of the subsequent months. No less than a hundred articles roundly criticized it, and it was rare indeed to find one that came to its defence. Even the Catholics of the left, who were at times fairly closely allied with Borduas (including journalist and future politician Gérard Pelletier; Jacques Dubuc, a friend of Pelletier; Robert Élie, the writer, art critic, and future director of the Canada Council for the Arts; and journalist André Laurendeau) withdrew their solidarity, joining the ranks of Roger Duhamel, Harry Bernard, Father Hyacinthe-Marie Robillard, and Father Ernest Gagnon, who were far more negative in their stance toward the ideas expressed in the manifesto.

Despite the immediate denouncements, the manifesto marked the beginning of profound social change in Quebec. Since the publication of the complete writings of Borduas, the originality of his thought is steadily becoming clearer. Every ten years, there are celebrations in Quebec commemorating the publication of Refus global, which signalled the dawn of the Quiet Revolution in Quebec.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements