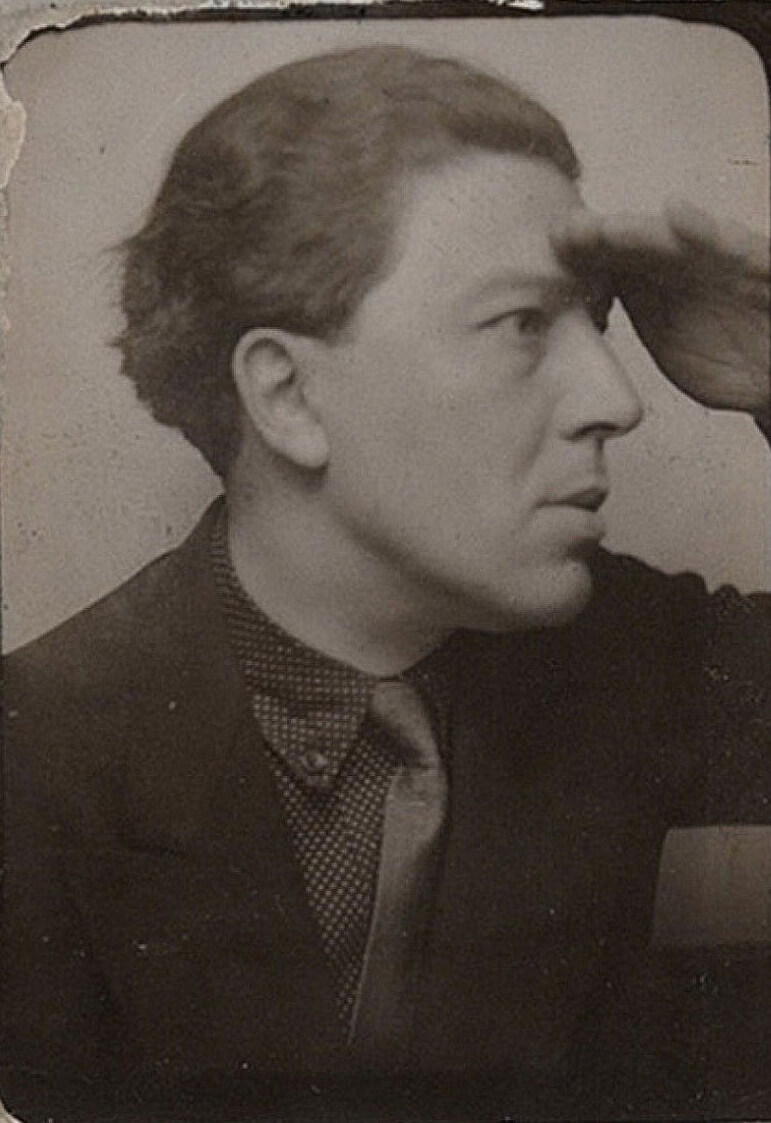

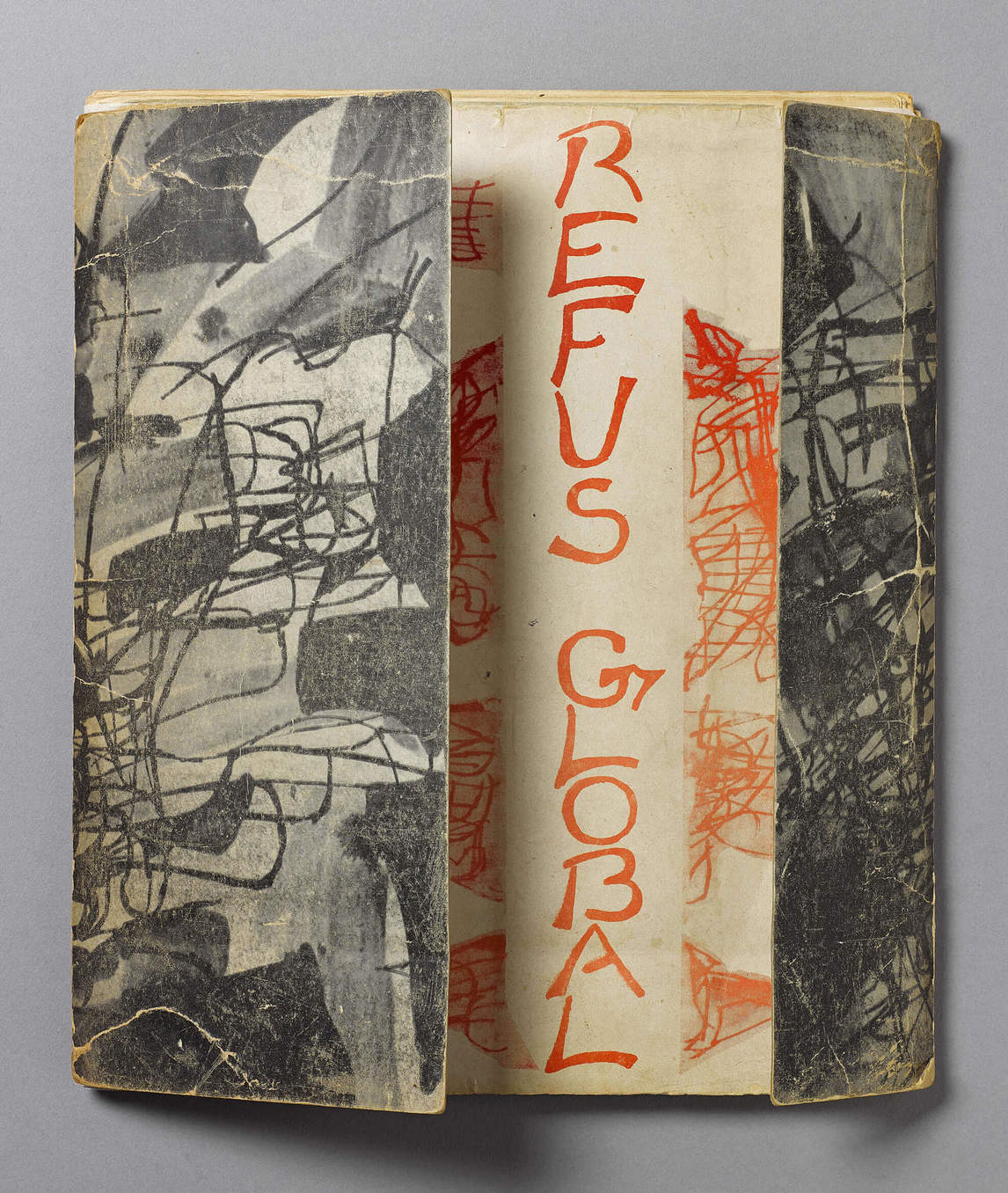

As a painter, a thinker, and the leader of the Automatistes, Borduas sought a new freedom to make art, rebelling against the stifling restrictions on culture and society in Quebec. His activities exhibited a remarkable coherence of ideas, which in turn led to an unusual coherence within this avant-garde group of artists and intellectuals. The Refus global manifesto, with Borduas as the principal author, had an immediate impact when it was published in 1948 and later contributed to the Quiet Revolution that swept Quebec in the 1960s.

Painting

Before the Surrealists, the highest goal of an artist was to imitate nature. Plato’s grievance against the artist was not that he imitates, but that he imitates only the appearance of things rather than reflecting their idea, or essence. Writing about tragedy, Aristotle transforms imitation into a kind of therapy aimed at purging or purifying the emotions of the spectator, who achieves catharsis. Philosophers gave a privileged place to imitation, or to one of its variations as defined by Leon Battista Alberti (1404–1472), when treating subjects of mythology, religion, or history. It follows that the painter who imitates nature or illustrates a story has—before even setting brush to canvas—a clear idea of the scene. In this vein, the historian Louis Hourticq writes: “When Poussin ‘found the idea’ of The Ravishing of St. Paul, he … did not begin his work until all parts of the painting and their relationship to each other were conceived in his mind.” It is this practice of preconception of a work that would be questioned by the Surrealists, and later by Borduas and the Automatistes.

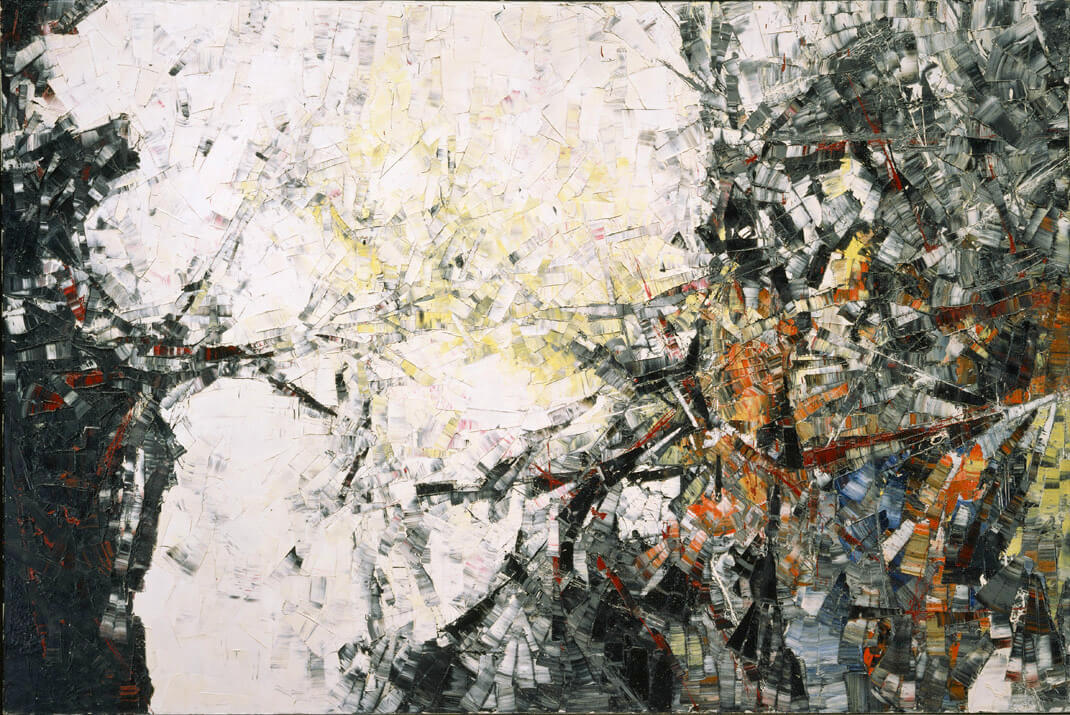

Under the influence of Surrealism, Borduas discovered an entirely different way to think about the production of a painting. He read texts by the French poet André Breton in which Breton describes what might be called “automatic painting,” somewhat akin to the automatic writing that he and other Surrealist writers were beginning to practice.

Breton proposes creating a painting that is not preconceived. The painter, with no model to imitate and no iconographic program to follow, sets out on an adventure: instead of imitating, the painter must “create.” The old argument of Nature’s design being used to demonstrate the existence of God is turned inside out. It is no longer God who creates like an artist, but the artist who creates like God—ex nihilo, out of nothing. Painting without a preconceived idea, as Breton and the Surrealists recommend, was thus a radical challenge to the traditional idea of the artist as imitator and of the artist’s work as imitation.

If a work is not preconceived, can it be considered complete? The answer is not always easy, even for the painter. In this new concept of the act of painting, it could be said that the painter is a witness to the evolution of the work developing in front of his eyes. The artist can give the work a title once it is finished (for example, Sewing Machine), but the title will never correspond to a program set out at the beginning (“I will paint a sewing machine”); it will simply be one of several possible readings of a work now considered complete. Borduas sometimes adopted titles suggested by others for his paintings (for example, the biologist Henri Laugier titled Borduas’s gouache Chanteclerc, 1942).

Political Ideas

For the Automatiste artist, the act of painting found its correspondence in political ideas: it could be said that anarchy is the political equivalent of what Borduas and the Automatistes sought to achieve through their art. In a text sometimes described as the first draft of the Refus global manifesto, Borduas clearly alludes to anarchist ideas: “We believe that social conscience can develop so that one day mankind will govern itself through a spontaneous, unrehearsed sense of order.”

The anarchist social order is not imposed by external forces such as the church or the state; it is achieved through the play of individual freedoms, where the only rule is that of respect for the freedom of others. The social order is indeterminate at the beginning, but anarchists believe it cannot fail to grow once spontaneous creativity is unchecked. Although this concept has been criticized as utopian, Sam Abramovitch, a close friend of Borduas, points out that the anarchists defended what they called the “good society.” In a book that searches for traces of anarchy in Quebec, the writer Mathieu Houle-Courcelles devotes several pages to the Automatistes and their connection with the anarchists in Montreal through the photographer and taxi driver Alex Primeau. The Automatistes certainly had a far greater affinity with the anarchists than with the Communists, who were strictly observant Stalinists for the most part and believed in art serving the people. The development of an Automatiste practice was informed by anarchist ideas.

The Refus global manifesto had a lasting influence on politics in Quebec. It was later credited with anticipating the Quiet Revolution in the 1960s.

The Group

Theories on the formation of societies often base a society’s origin on the idea of a contract or formal promise that commits members to respect certain behaviours that define the specific character of their group. The formation of the Automatistes could not be further from this model. The group began with informal gatherings at Borduas’s studio on Mentana Street in Montreal and then at his home in Saint-Hilaire after 1945; they also met at the home of Fernand Leduc (1916–2014), without Borduas. There was nothing resembling a contract. Rather, to borrow a concept from the eighteenth-century philosopher David Hume, one could speak of “conventions”: behaviours that take hold spontaneously within a group depending on needs—chief among them, of course, being solidarity among the members. But just like an Automatiste painting, the form that this solidarity would take was not determined in advance. No one could foresee in 1941 that the group would sign a manifesto in 1948.

In the end the solidarity of the Automatistes would prove to be somewhat fragile. In 1951 Jean-Paul Riopelle (1923–2002) published a short text in which he declared that automatism as a movement was a thing of the past. The text appeared in the catalogue for Véhémences confrontées (Opposing forces), an exhibition organized in Paris by the critic Michel Tapié de Céleyran and the painter Georges Mathieu (1921–2012). Riopelle’s position here was paradoxical, since he remained faithful to the idea of chance in the evolution of a painting—he even spoke of “total chance”—an idea that corresponds perfectly to painting without preconception.

Fernand Leduc, influenced by the thinker and writer Raymond Abellio, adopted ideas that no longer resonated with the anarchist ideas expressed in Refus global; yet Leduc stayed very attached to the Automatistes, as his correspondence with Borduas amply demonstrates. Leduc’s painting, however, was more in line with the subsequent Plasticiens avant-garde movement than with the work of Borduas, Marcel Barbeau (b. 1925), Jean-Paul Mousseau (1927–1991), Pierre Gauvreau (1922–2011), or Riopelle.

The Automatistes had a powerful impact on the history of art in Quebec, and in the eyes of the world. No other Canadian movement displayed such coherence in life, in art, in ideas, and in friendship.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements