Study for Torso or No. 14 1942

Paul-Émile Borduas, Study for Torso or No. 14 (Étude de torse ou No14), 1942

Gouache on paper, 57 x 41.8 cm

Private collection

This painting is a good example of an early Automatiste work: executed without preconception. Borduas did not say to himself, “I am going to paint a female torso”; he recognized the subject in an instant when the work was completed. This is one of forty-five gouaches shown at the Ermitage, an exhibition hall owned by the Collège de Montréal, at 3510 Côte-des-Neiges. No other exhibition space could be found for these works, then judged to be “surrealist” and very “abstract.” For a long time they were titled simply “Abstraction” and numbered, though in Borduas’s papers they were identified only by a number and (in some cases) by a literary title.

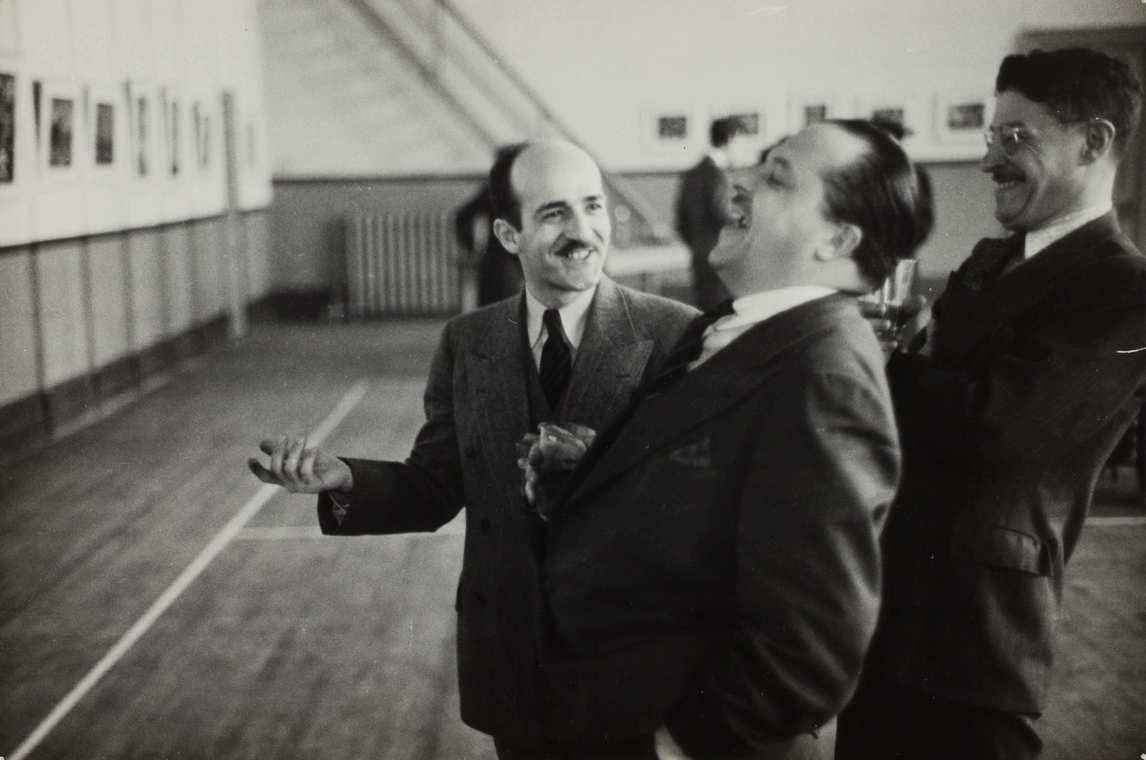

Today the gouaches are easy to understand, but they presented quite a challenge to two critics in 1942, Henri Girard and Charles Doyon, despite their receptiveness to “modern art.” Photographs taken at the exhibition capture the critics standing in front of Study for Torso with Borduas. It was only after the artist’s explanations that they understood the work. Borduas believed that the exhibition of multiple works by one artist was preferable to the limited impact offered by group exhibitions that show only a single work by each artist. He was quoted in Canadian Art magazine, recalling the experience of exhibiting the gouaches at the Ermitage:

My own conviction dates from the following experience: in 1942 after having gladly let my friends see the series of gouaches “automatiques,” I was forced to observe that, from the most cultivated European to the most ignorant Canadian, the same reactions occurred; the only difference apparent was one of tempo. From the first until the fourth or fifth gouache, my friends looked without seeing, without showing any sign of understanding, in the slightest, their plastic significance. This only began to change after the fifth or, according to the spectator concerned, after the tenth example of my work, but, for all of them, from then on until the end, the sense of communion became increasingly stronger. Although I was only painting by successive waves, I found after 1942 that each time I showed a new series of productions, evidence of the same kind of behaviour was forced upon me.

Whereas some of the gouaches—for example, Sewing Machine or No. 1 (La machine à coudre ou No1), 1942—adopt the format of a still life, Study for Torso takes the form of a standing figure, if not a portrait: that is, the orientation of the composition (horizontal or vertical) reflects the formats Borduas employed earlier in his figurative works. The unconscious springs from the old consciousness! Perhaps it was one of these works that inspired Charles Doyon to suggest that Borduas’s work went through an “undulatory period” the term, however, did not take hold.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements