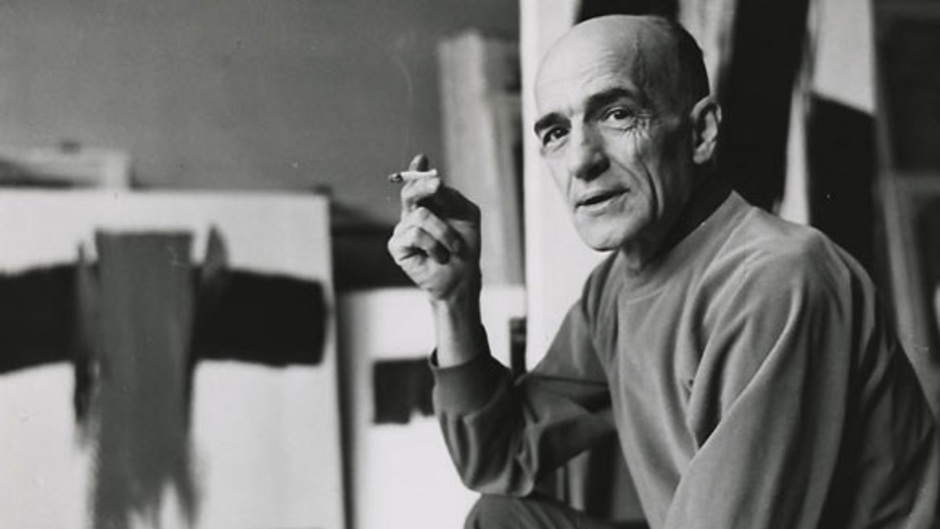

The leader of the avant-garde Automatiste movement and the principal author of the Refus global manifesto of 1948, Paul-Émile Borduas had a profound influence on the development of the arts and of thought, both in the province of Quebec and in Canada. Borduas was born in 1905 in the village of Saint-Hilaire, where he apprenticed with the painter Ozias Leduc before studying art in Montreal and in Paris. After the publication of Refus global, he lost his teaching position in Montreal and within a few years left Quebec for New York and then Paris. Borduas achieved some measure of international recognition in his final years in Paris, where he died in 1960.

Early Education

Paul-Émile Borduas was born in Saint-Hilaire, a village some forty kilometres east of Montreal, on November 1, 1905, the fourth of seven children. His father, Magloire Borduas, was a carpenter and blacksmith. His mother, Éva Perrault, was known in the village for the beauty of her garden.

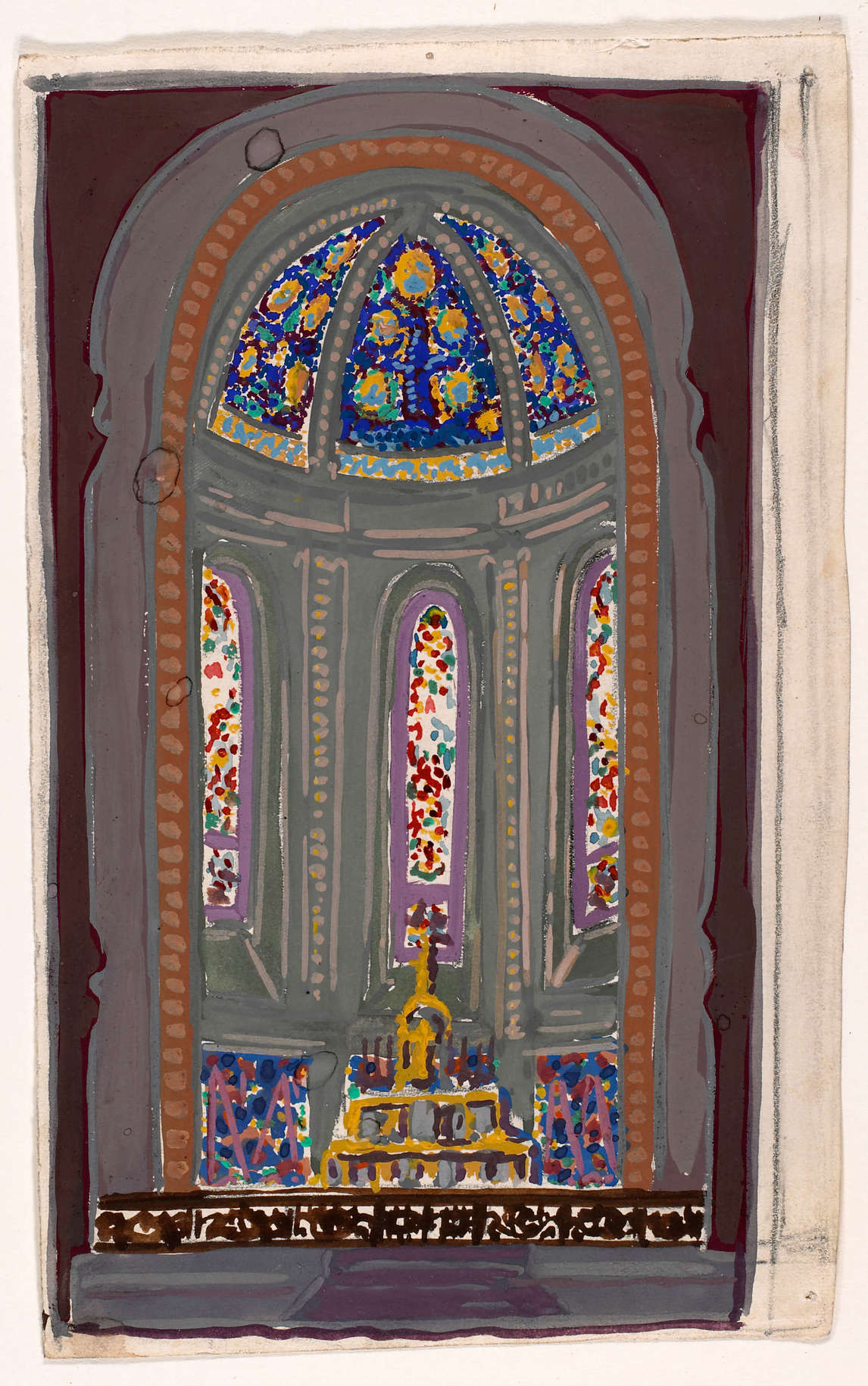

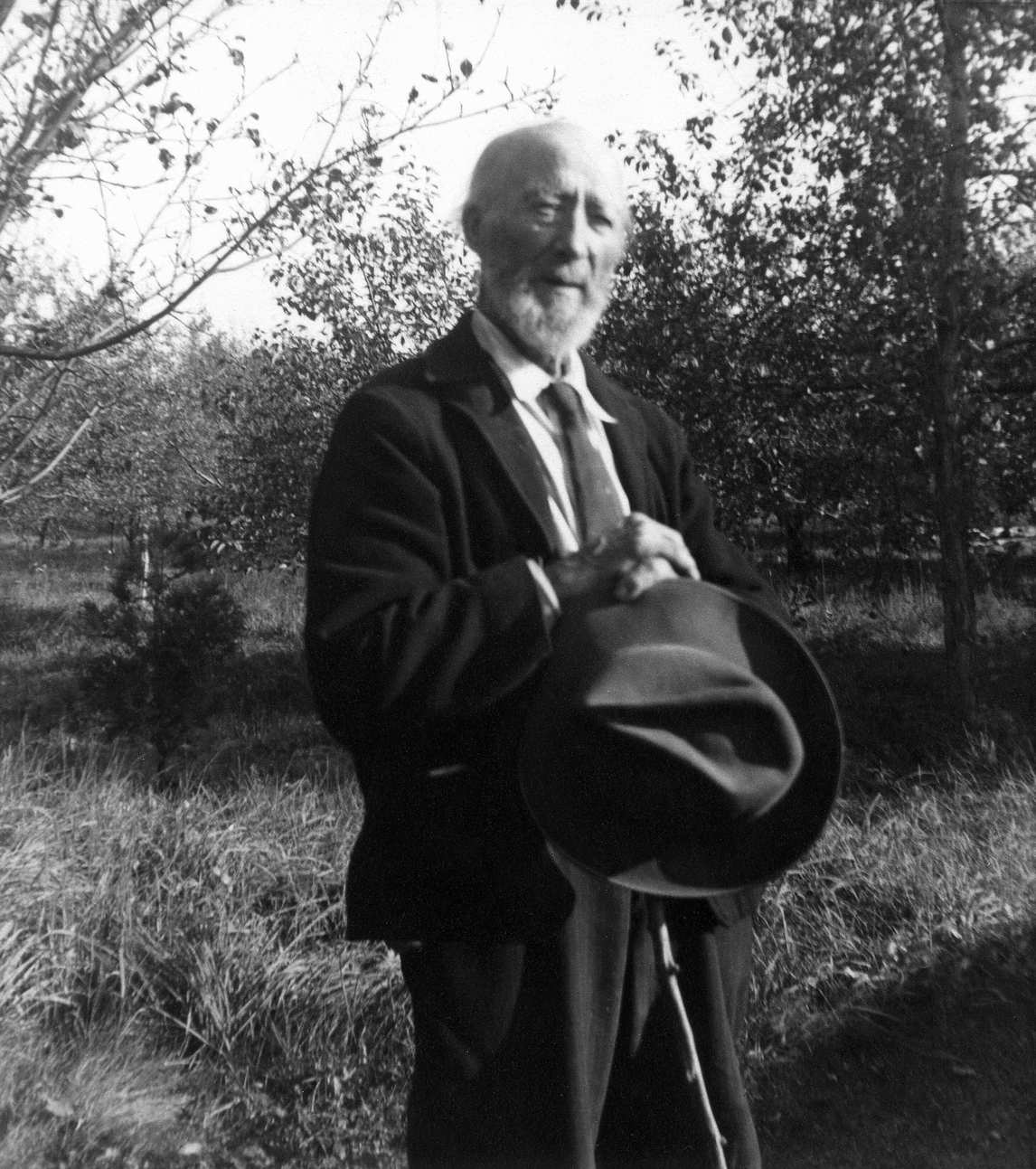

As a boy Borduas suffered from poor health; he attended the village school for only five years and received some private tutoring. Borduas stated that his schooling ended at age twelve, around 1917, though this has not been confirmed. We do know that in 1921, when Borduas was sixteen, the painter Ozias Leduc (1864–1955), who also lived in Saint-Hilaire, took him on as an apprentice in church decoration. Leduc subsequently encouraged him to register at the École des beaux-arts in Montreal in 1923, the year after the school opened.

Borduas benefited from two distinct forms of training in the visual arts, owing to his apprenticeship with Leduc and his studies at the École des beaux-arts. He would retain fond memories of Leduc, but among his professors at the École only Robert Mahias (1890–1962) was singled out by him for cautious praise. Borduas quarrelled with Charles Maillard, an academic painter who despised modern art; Maillard had been appointed director of the school in 1925 after the departure of Emmanuel Fougerat. Borduas believed that Maillard damaged his reputation and hindered his progress for years to come. After graduating from the École des beaux-arts in 1927, Borduas for a brief time taught drawing in Montreal—until Charles Maillard arranged to have him replaced as drawing teacher at the École du Plateau.

Borduas then had the opportunity to train as a religious painter and church decorator in France. On Ozias Leduc’s recommendation, he was funded by Olivier Maurault, parish priest of Montreal’s Notre-Dame Church (now known as Notre-Dame Basilica), to study in 1928–29 and perhaps in 1930 at the Ateliers d’art sacré in Paris, under the direction of Maurice Denis (1870–1943) and Georges Desvallières (1861–1950).

Although only passably academic, the lessons at the Ateliers allowed Borduas to meet the artist Pierre Dubois as well as the Dominican friar Marie-Alain Couturier, who sought to renew sacred art and architecture with modern styles and materials. Borduas worked with Dubois on church decoration projects in the Meuse region, where churches damaged in the First World War were being rebuilt. In Paris he had the opportunity to visit exhibitions of work by Pablo Picasso (1881–1973), Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919), and Jules Pascin (1885–1930). Borduas would have extended his stay in France, but his funding was exhausted.

Return to Canada

Borduas returned to Canada on June 19, 1930. In the harsh economic climate of the Great Depression he was unable to secure independent contracts for church decoration. For a time he assisted Ozias Leduc, working on the Saints-Anges Church in Lachine. To make ends meet he taught drawing at primary schools and at the Collège André Grasset in Montreal.

On June 11, 1935, Borduas married Gabrielle Goyette, from Granby, the daughter of a doctor and a trained nurse herself. They had three children—Janine, Renée, and Paul. Until 1938 the family lived in a house near Lafontaine Park in Montreal, at 953 Napoleon Street.

In 1937 Borduas finally secured a position at the École du meuble, where Jean-Marie Gauvreau (1903–1970) was director. Most of Borduas’s teaching career was spent at this school, which would prove to be a stimulating environment for him. His career reached a turning point in 1938 when he discovered Surrealism and the works of the French writer André Breton. Borduas was particularly influenced by some advice given by Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) to his students, referred to in a text by Breton. Essentially, Borduas took from the lesson the idea of painting without having a preconceived idea—in a sense “automatically.”

At the École du meuble Borduas met the architect Marcel Parizeau and the art historian and critic Maurice Gagnon, who was hired at the same time. Soon he would also become acquainted with a number of like-minded young artists and intellectuals who were keen to push the rigid boundaries of Quebec society. They included his students Jean-Paul Riopelle (1923–2002), Marcel Barbeau (b. 1925), and Roger Fauteux, and through them some students from the École des beaux-arts: Françoise Sullivan (b. 1923), Pierre Gauvreau (1922–2011), Fernand Leduc (1916–2014), and Maurice Perron (1924–1999).

Borduas also met Jean-Paul Mousseau (1927–1991), then at the Collège Notre-Dame in Montreal, and later, Marcelle Ferron (1924–2001), after she left the École des beaux-arts in Quebec City. Under Borduas’s leadership these artists formed the group that came to be known as the Automatistes, the future signatories of the manifesto Refus global (total refusal).

In the early 1940s the Automatistes met at Borduas’s studio on Mentana Street or at Fernand Leduc’s studio; these spaces offered the group members the freedom to broach any subject—political, religious, social, or artistic—and to discuss each other’s opinions and ideas. They also participated in so-called forums—public debates on modern painting, non-representational work, and abstraction—held in schools in Montreal (Externat classique Sainte-Croix, Collège Saint-Laurent) or in nearby communities (Collège classique de Sainte-Thérèse). These forums were sometimes accompanied by exhibitions.

Borduas started to experiment with nonfigurative work, and his exhibition of gouaches in 1942 at the Ermitage, an exhibition hall owned by the Collège de Montréal, drew the attention of the critics. He continued to experiment in this direction, and the following year he exhibited abstract oil paintings at the Dominion Gallery in Montreal.

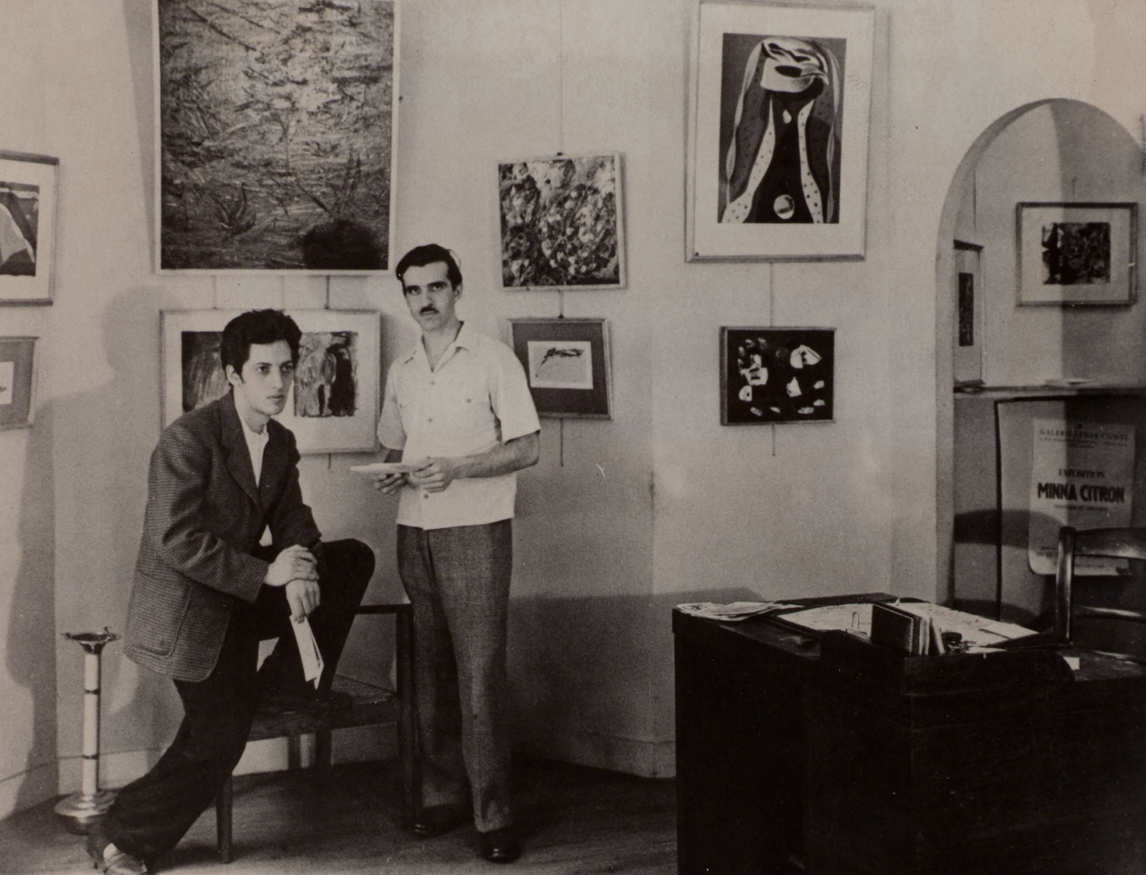

Automatiste Exhibitions

The Automatistes were eager to mount public exhibitions of their recent work, which was nonfigurative and abstract. Since no commercial gallery would agree to exhibit all the members of the group, even with Borduas’s endorsement, they exhibited in makeshift venues: in 1946 on Amherst Street, in Montreal’s east end, in a hall where Julienne Saint-Mars-Gauvreau—the mother of Pierre Gauvreau and Claude Gauvreau, a playwright and poet—had organized gatherings for soldiers during the war; then in early 1947 at the home of Mme Gauvreau, at 75 Sherbrooke Street West. In the summer of 1947, when Fernand Leduc and Jean-Paul Riopelle organized an exhibition at a new gallery in Paris, the Galerie du Luxembourg, the group seized the opportunity to show their work in France.

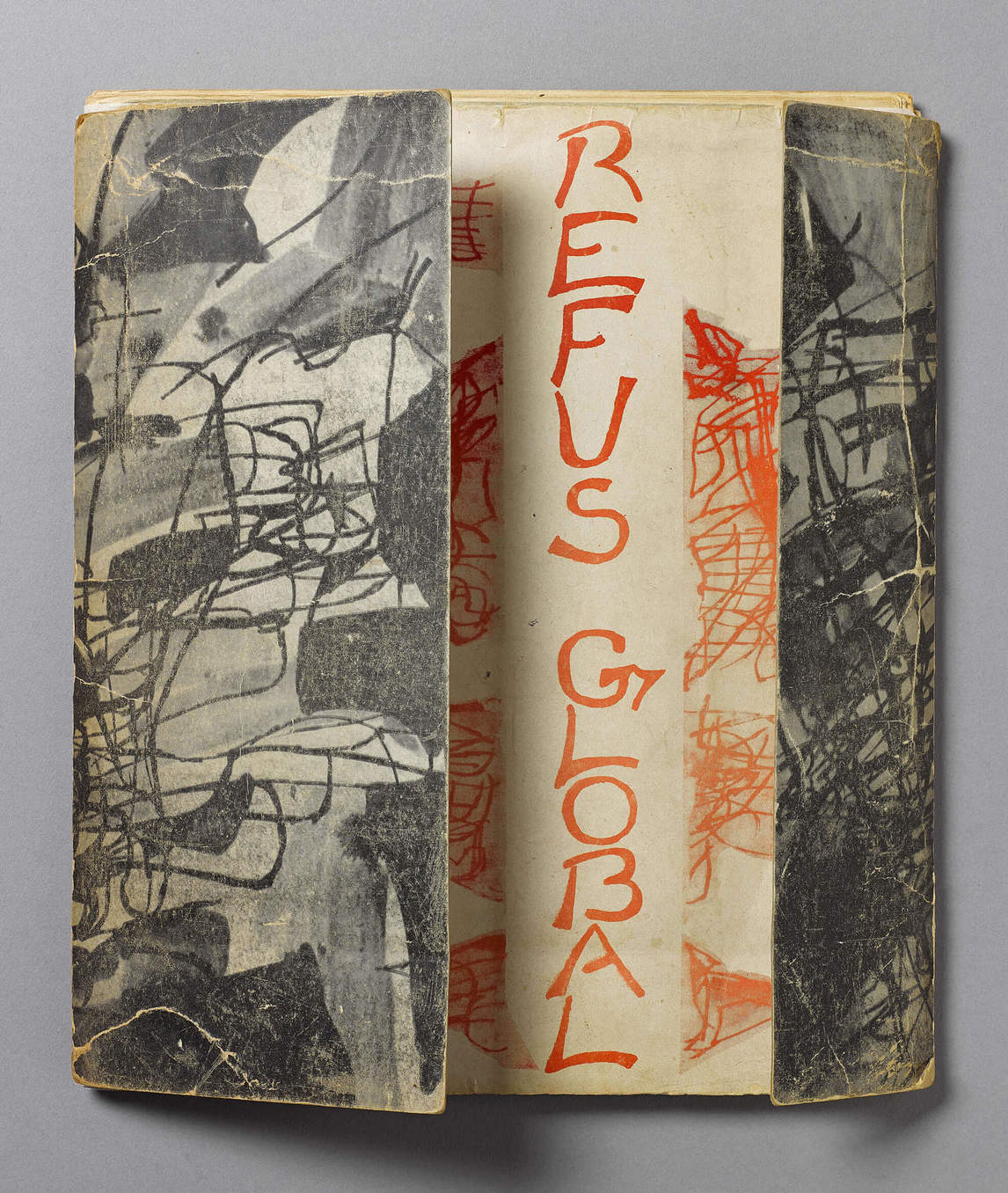

Refus global

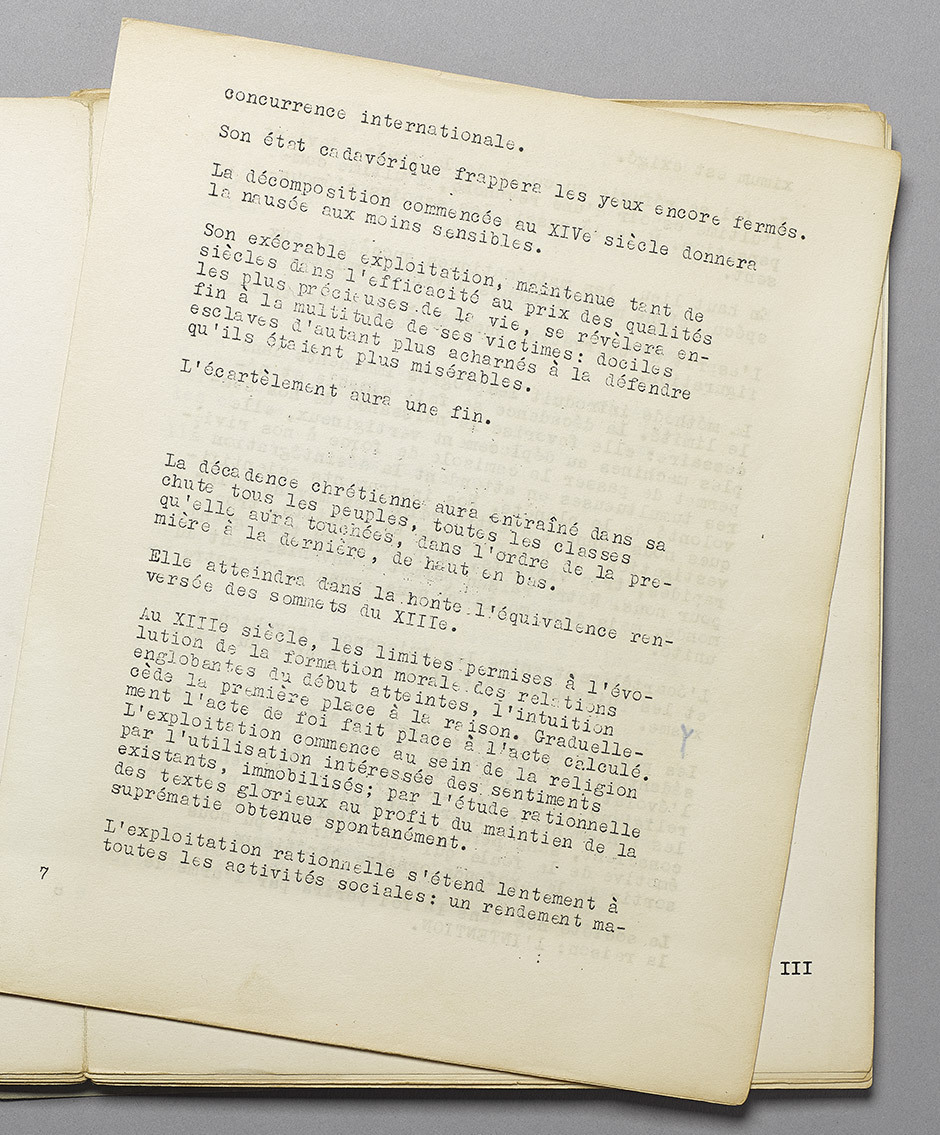

Determined to make their mark, and encouraged by Riopelle on his return from Paris where he had signed the Surrealist manifesto Rupture inaugurale, the Automatistes initially decided that their next exhibition in Montreal would be accompanied by a manifesto. Borduas took on the task of writing the main text, but Bruno Cormier and Françoise Sullivan, as well as Claude Gauvreau and Fernand Leduc, also contributed. The publication included reproductions of paintings by members of the group and photographs of Claude Gauvreau’s theatre productions. In the end the group postponed the third Montreal exhibition of the Automatistes in favour of making an event out of the launch of the manifesto. Refus global was published in a first edition of four hundred copies printed on a Gestetner duplicating machine; the copies went on sale at the Librairie Tranquille in Montreal on August 9, 1948.

In this manifesto Borduas launched a frontal attack on the parochialism (esprit de clocher, as it was called) in Quebec, the stifling dominance of Catholicism, and the narrow nationalism of the provincial government under Premier Maurice Duplessis. The immediate consequence was Borduas’s suspension without pay from his position at the École du meuble, effective September 4, 1948. The provincial minister of youth and social welfare explained the decision as follows: “Because the writings and the manifestos [sic] he publishes, as well as his state of mind, are not conducive to the kind of teaching we wish to provide for our students.”

The repercussions of the manifesto’s publication extended far beyond Borduas’s career. His young (and not so young) disciples were also affected. Some, like Riopelle and Leduc and their respective partners, chose to leave Quebec for a life in France. Marcelle Ferron would later follow the same path. But others, those known as the “young brothers”—Marcel Barbeau, Jean-Paul Mousseau, and Claude Gauvreau—became even more interested in the political cause. Responding to the manifesto’s exhortation to “refuse to be confined to the barracks of plastic arts,” they sought to take their art and their ideas into the public domain, publishing polemics in journals and newspapers. Concerned that they were operating under an illusion with regard to the impact they could have on prevailing sensibilities, in 1950 Borduas wrote his essay “Communication intime à mes chers amis” (Intimate message to my dear friends), in which he recalls: “Poetical work carries a profound social potential, but [it] is realized slowly—for it has to be assimilated by a multitude of men and women with nothing to assist them but the power of the work itself.”

Borduas found himself without work or reliable resources in Quebec. He supported himself through his art (watercolours, small-scale paintings, and sculptures), supplemented by teaching drawing to the children of Saint-Hilaire. This situation began to weigh on his family and, upon his return from a trip to Toronto in October 1951, Borduas found an empty home. Gabrielle had left and taken their children with her.

In New York

Desiring above all to leave Quebec, Borduas was left with no choice but to sell his home in Saint-Hilaire and pursue his goal of emigrating to the United States. New York was his destination, but first, in the summer of 1953, he rented a studio by the sea in the artists’ colony in Provincetown on Cape Cod, Massachusetts. Here he may have encountered the painter Hans Hofmann (1880–1966), who held summer workshops in the town. Hofmann had spent several years in Paris before moving to the United States, and so Borduas, whose English was then rudimentary, could have conversed with him in French. However, this encounter remains entirely conjectural.

date unknown.

In New York Borduas moved into 119 17th Street East in Greenwich Village. He describes it in a letter to his former teacher Ozias Leduc: “Here, I’ve found a superb studio—the only one available, apparently—immense, flooded with light, all white. Naturally the rent is insane.” The collection of exhibition catalogues discovered among his belongings at the time of his death would imply that Borduas had attended art shows and visited museums while in New York, but Sam Abramovitch, an independent scholar and friend of the Automatistes, has stated that Borduas “rarely went out,” and that the catalogues were those that he had given to the artist.

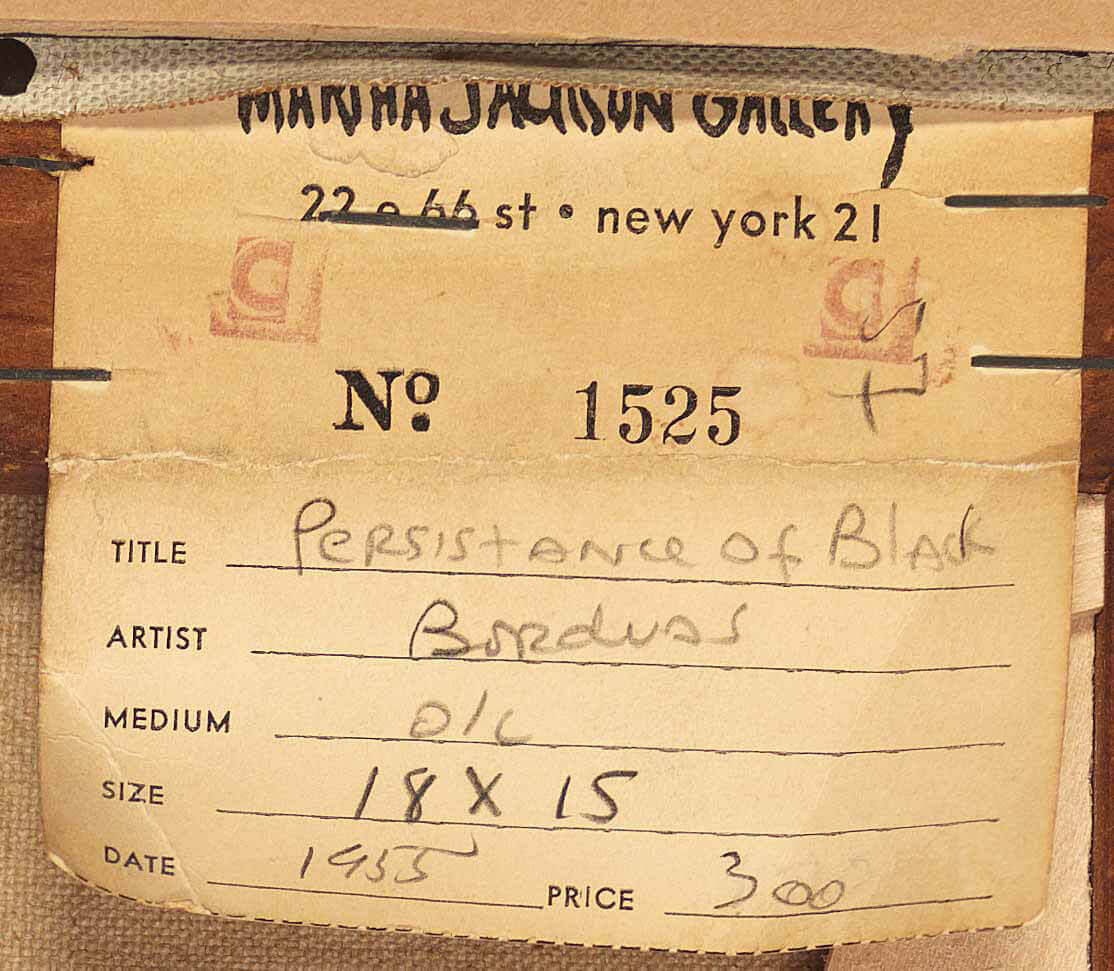

Borduas immediately began to work toward a first exhibition in New York. On October 13, 1953, roughly two weeks after his arrival, he attended an opening at the Passedoit Gallery, at 121 57th Street East, where he hoped to exhibit. He must have been roundly bored: featured were pseudo-Cubist paintings by a Stefano Cusumano, whom no one knew. In any event, Georgette Passedoit soon extended an offer to exhibit in her gallery. On November 16 Borduas was able to inform the critic Guy Viau that “all is decided and signed: opening of my exhibition on January 5.” By 1955 Borduas wished to be represented in New York in a more dynamic venue than the Passedoit Gallery. He approached the Martha Jackson Gallery, then located at 22 East 66th Street.

The Martha Jackson Gallery was not yet well known, having opened just the year before. In 1954, a year prior to Borduas’s connection with the gallery, Martha Jackson had visited Europe, signing contracts with Karel Appel (1921–2006), Sam Francis (1923–1994), and John Hultberg (1922–2005). Shortly after Borduas joined the gallery, Jackson organized a successful exhibition of the work of Willem de Kooning (1904–1997). Borduas’s papers include a short note dated September 20, 1955, in which he declares that he left four paintings on consignment at the Martha Jackson Gallery. It was a good move. Martha Jackson was interested in his work and would continue to represent him, even after he left New York.

In Paris

Despite what appeared to be an excellent start for Borduas on the New York scene, he left the city for Paris, boarding the Liberté on September 21, 1955, accompanied by his daughter Janine. He told his friend Gilles Corbeil that “this departure for Paris may well be the high point of the adventure.” Knowing how things would turn out, it is impossible not to be touched by sadness at all this hope and optimism.

Martha Jackson had tried to put him in touch with critics in Paris, in particular Michel Tapié de Céleyran, who coined the term art autre (other art)—a poorly defined expression since it included both figurative artists, such as Jean Dubuffet (1901–1985), Jean Fautrier (1898–1964), and Willem de Kooning, and abstract painters like Wols (1913–1951), Hans Hartung (1904–1989), and Serge Poliakoff (1906–1969). It was Jackson who introduced him to the gallery Arthur Tooth & Sons in London and to “two German dealers,” a reference to the Galerie Alfred Schmela in Düsseldorf—two contacts that were encouraging, especially the former. Jackson visited Borduas’s studio in Paris to stock up on recent paintings and continued to exhibit his work in her gallery in New York.

His Paris period, however, from 1955 to 1960, was a difficult time for him. He failed to secure a solo exhibition until 1959, at the Galerie Saint-Germain, one year before his death. Still, throughout this period he managed to maintain his contacts with Canadian galleries (Max Stern of the Dominion Gallery in Montreal, and the Blair Laing Gallery in Toronto) and collectors (Gisèle and Gérard Lortie, Gilles and Maurice Corbeil, Gérard Beaulieu, and others). And he was included in prestigious exhibitions in Europe and North America as a representative of Canadian art. Nevertheless, he never achieved a breakthrough on the Parisian gallery scene, nor any meaningful recognition of his importance as a painter—certainly nothing in comparison to Riopelle, who would remain the most acclaimed Canadian painter during this time.

After Borduas’s daughter Janine, who suffered from a mental illness, returned to Montreal, he lived alone in Paris. His precarious resources, failing health, and small circle of Canadian friends convey an impression of difficult circumstances. The exhibitions he attended were either avant-garde events featuring artists such as Georges Mathieu (1921–2012), Lucio Fontana (1899–1968), or Alberto Burri (1915–1995), or performances at the edge of art, like those of Yves Klein (1928–1962), creator of the Symphonie monocorde and of paintings executed by using nude models as “brushes.”

Thanks to some sales of his work to collectors or to Canadian dealers who dropped into his studio, Borduas was able to purchase a Citroën, which he named La veuve joyeuse (The merry widow). The car allowed him to take a break from his work in Paris and travel to Switzerland, Italy, and Greece.

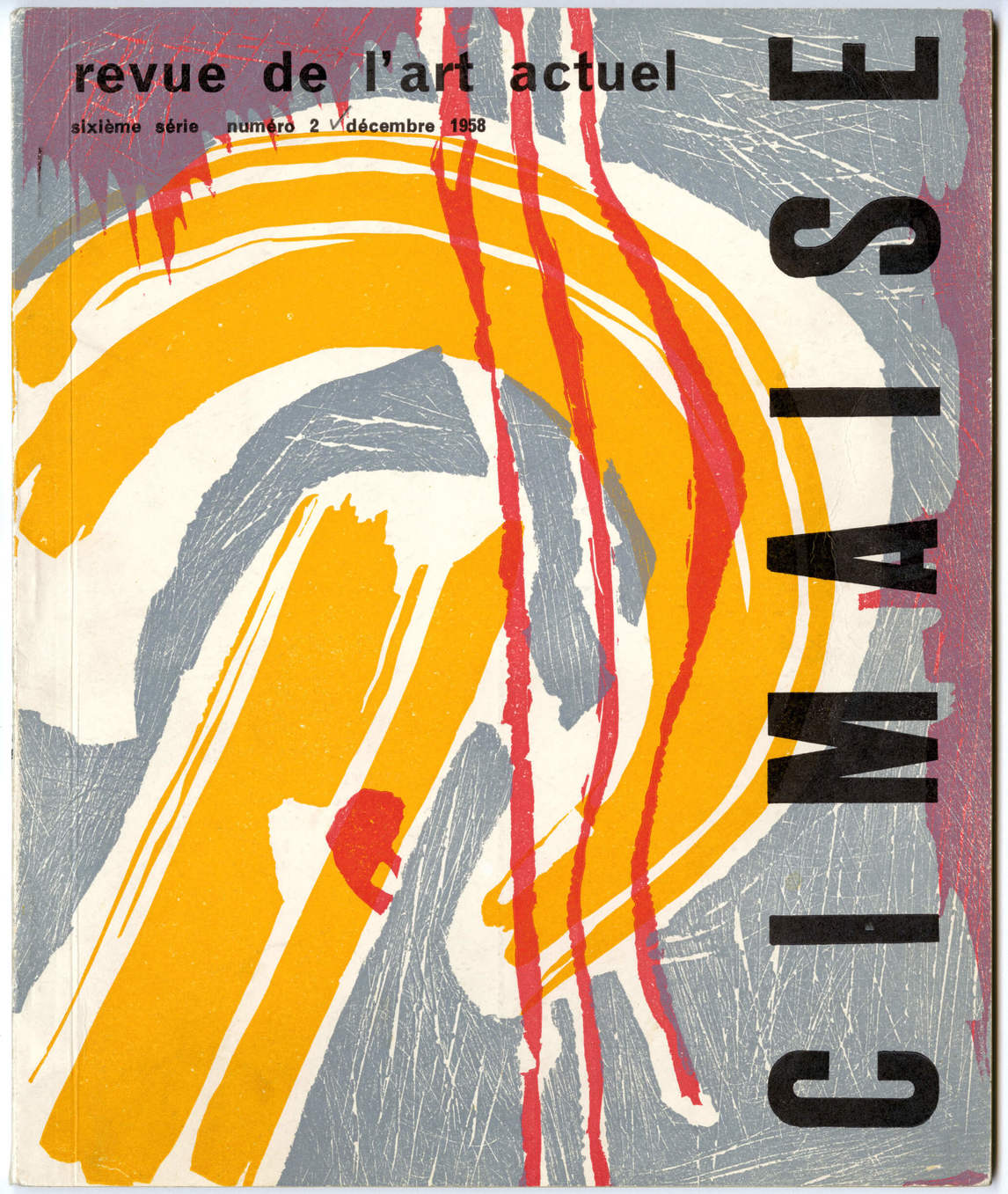

Borduas was one of the participants in Spontanéité et réflexion, an exhibition in Paris organized by the art historian Herta Wescher, who had co-founded the Parisian art journal Cimaise in 1953. Marcelle Ferron also participated, as did Max Weber (1881–1961), K.R.H. Sonderborg (1923–2008), Esther Hess (b. 1919), Joseph Zaritsky (1891–1985), and Don Fink (b. 1923). The exhibition was held at the Galerie Arnaud, from March 5 to 31, 1959. Borduas showed three canvases, including Composition 37, 1958, which was reproduced in Cimaise. His participation received special mention by Pierre Restany, an influential critic who, together with Yves Klein, would become a supporter of Nouveau réalisme (New Realism), an art movement founded the following year and represented by Arman (1928–2005), Martial Raysse (b. 1936), Daniel Spoerri (b. 1930), Jean Tinguely (1925–1991), César (1921–1998), and others. Restany writes of the exhibition: “Borduas dominates the group with his remarkable harmonic constructions based on broad, squared-off strokes integrated into a space of subtle whiteness enlivened with chromatic resonances.”

This was the first major recognition of his work in Paris. Two months later Borduas had his first solo exhibition in the city, from May 20 to June 30, 1959, at the Galerie Saint-Germain. A small art rental gallery in the same neighbourhood as the Galerie Arnaud, the Galerie Saint-German had just opened its doors to the public, though would not last long. The precise line-up of the seventeen works by Borduas on display is unknown, with the exception of one painting, Abstract in Blue (Abstraction en bleu), 1959, which was reproduced on the invitation.

Abstract in Blue is a remarkable work, reflecting Borduas’s growing interest in a kind of calligraphy composed of abstract signs. Should we read this as a reflection of his oft-expressed desire to visit Japan? But it goes without saying that Borduas’s language is not a language of signs. The canvas consists essentially of two movements: one horizontal, in the black; and one vertical, in the blue, splitting into two branches. The result is a sense of authority in the gesture and in the necessity of the shape.

Borduas died of a heart attack, alone in his studio on the rue Rousselet on February 22, 1960. His easel held a canvas that was nearly all black. Composition 69 is considered his last painting. Borduas worked until the very end.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements