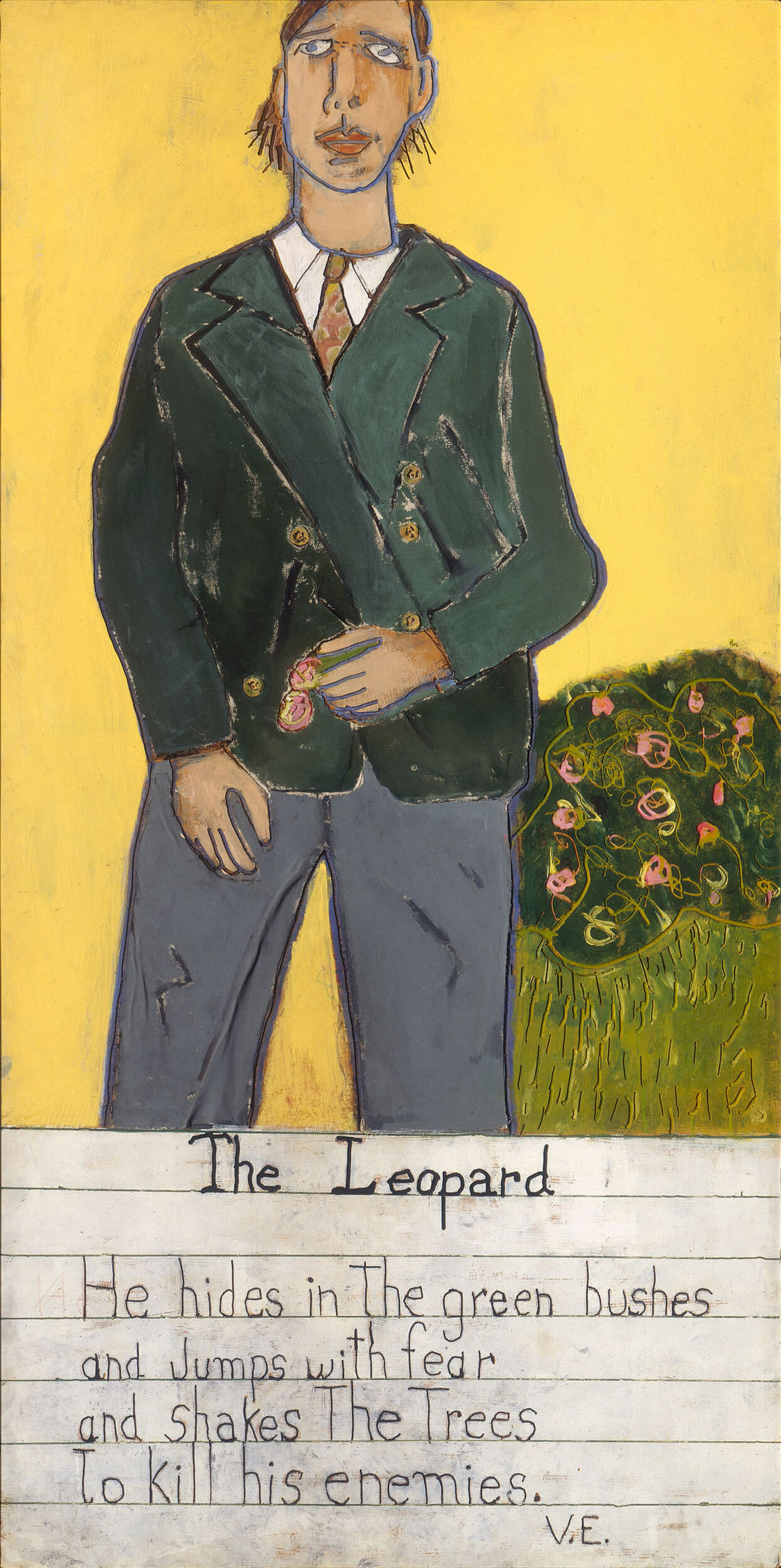

The Bandaged Man 1973

Paterson Ewen, The Bandaged Man, 1973

Acrylic and cloth on plywood, 243.8 x 121.9 cm

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

Paterson Ewen shied away from portraits, just as he shied away from people; they made him uncomfortable. Yet in 1989 Ewen stated: “People think of me as a landscape painter because I’ve done hundreds of landscape images, but my half dozen portraits are my greatest works.” Bandaged Man is probably the best known of the artist’s portraits. Like the artist himself, this portrait is awkward, unnerving, and disturbingly captivating. We are stared at intensely, faced by an individual wrapped in bandages who is represented in a naive, distorted way that reflects a damaged self. At the same time, the image seems to contain a spark, an inner life force that suggests the individual will forge ahead.

Bandaged Man was inspired by an etching in an encyclopedia that accompanied an entry about different types of bandages. As Ewen explained:

It intrigued me so much I thought I would do a bandaged man on a four-by-eight piece of plywood using canvas as the bandage. I was a bit of a wreck at the time after my year in Toronto. And as I went along with the bandaged man I began to realize it looked more and more like me. It had my body and it became very scary. When I went to bed at night I used to turn it to the wall. There’s no question it is a kind of self-portrait. Maybe it’s going too far but I’m not so sure. To say maybe I did that at a time when I was a wreck and needed bandages.

The background colour is reminiscent of the standard light green walls of a hospital, a place he was all too familiar with.

Ewen’s portraits have little in common, and therefore they cannot be considered a series. For the most part, though, their sporadic appearance suggests they mark significant events in his life. Bandaged Man relates to Ewen finally being able to heal after a traumatic eight-year period that started with his leaving his first wife, Françoise Sullivan (b. 1923), in 1965. His Portrait of Vincent, 1974, celebrates his oldest son’s poetic gifts. The 1986 self-portrait likely represents Ewen’s attempt to regain a sense of self, or wholeness, after his companion, Mary Handford, left to study architecture in Waterloo, Ontario—a separation that Ewen did not handle well. The portraits are fascinating punctuation marks in the career of an artist who generally shied away from the human figure.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements