Paraskeva Clark was a formalist and a realist by training and as an artist. “I am primarily after reality—after the pulsation of life of all objects around me to be painted,” she said. Her interest in form set her apart from many of her Toronto contemporaries, who focused on nationalist content. She developed as an artist through keen observation of her new environment and the work of other painters, as well as by experimenting with different styles and techniques. Though her forays into abstraction were not entirely successful, they indicate her need to be connected with the world around her.

Russian Influences

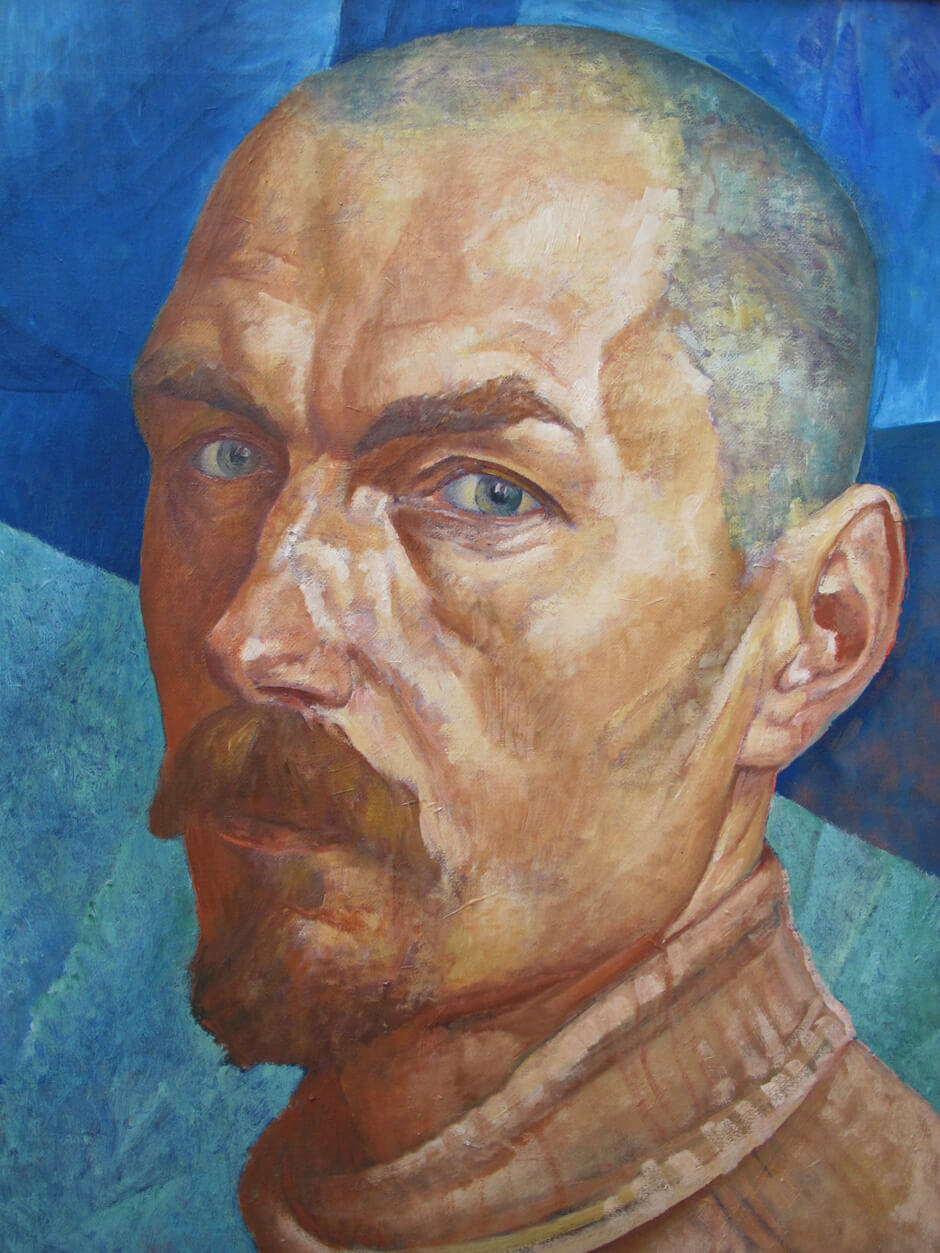

No examples remain of Paraskeva Plistik’s student work, but the few pieces she made in Paris (1923–30) and her early work in Toronto (1931–36) document her development as an artist. From what she wrote later about her art education, it appears that she learned the fundamentals from her first two teachers in Russia: the landscape painter Savely Zeidenberg (1862–1924) and her composition and life-drawing instructor Vasili Shukhaev (1887–1973). Clark admitted, however, that she struggled with figural composition in Shukhaev’s class, and that his use of thickly applied oils and his sanguine chalk drawings did not appeal to her. It was Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin (1878–1939), her teacher at the Free Art Studio (svoma) in Petrograd for just over a year in 1920–21, who had a deep and lasting influence on her work.

Clark was drawn to the classical simplicity in works by Petrov-Vodkin, a formalist-realist painter and follower of Paul Cézanne (1839–1906). Later in life, she explained that she liked the “reasonable” (rational?) quality in Cézanne and Pablo Picasso (1881–1973). In Petrov-Vodkin’s class, Plistik learned to construct a head by discerning the smaller geometrical shapes within it.

Petrov-Vodkin had devised the “spherical perspective” system—a new method of depicting forms and space that he published in 1933 in Euclidean Space. According to the Russian artist Kirill Sokolov (1930–2004), it included a complex system of reversed perspective based on Petrov-Vodkin’s study of thirteenth-century Italian painting, icon painting, and Gothic art, and was distinguished by a “planetary” feeling for space (Petrov-Vodkin’s term). In landscapes, the horizon line was placed very high and fell away at the sides of the picture to give the impression of a viewpoint looking down over the curving surface of the earth.

Petrov-Vodkin’s method took into account the movement of the artist in relation to the object and afforded several viewing points (unlike the classical “one-point perspective” introduced during the Italian Renaissance). It also involved his colour theory (he gave special status to the primary colours red, blue, and yellow), which Sokolov speculates was influenced by Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944) in addition to earlier art forms. His famous Bathing the Red Horse, 1912, which sums up his theories, inspired Clark’s Bathing the Horse, 1937. Learning this new method of depicting forms and space, Clark commented: “It seemed like getting new limbs to penetrate into space and to perceive the motion all around and to put it on canvas.” At the time when Clark was studying with Petrov-Vodkin, he was painting austere still lifes.

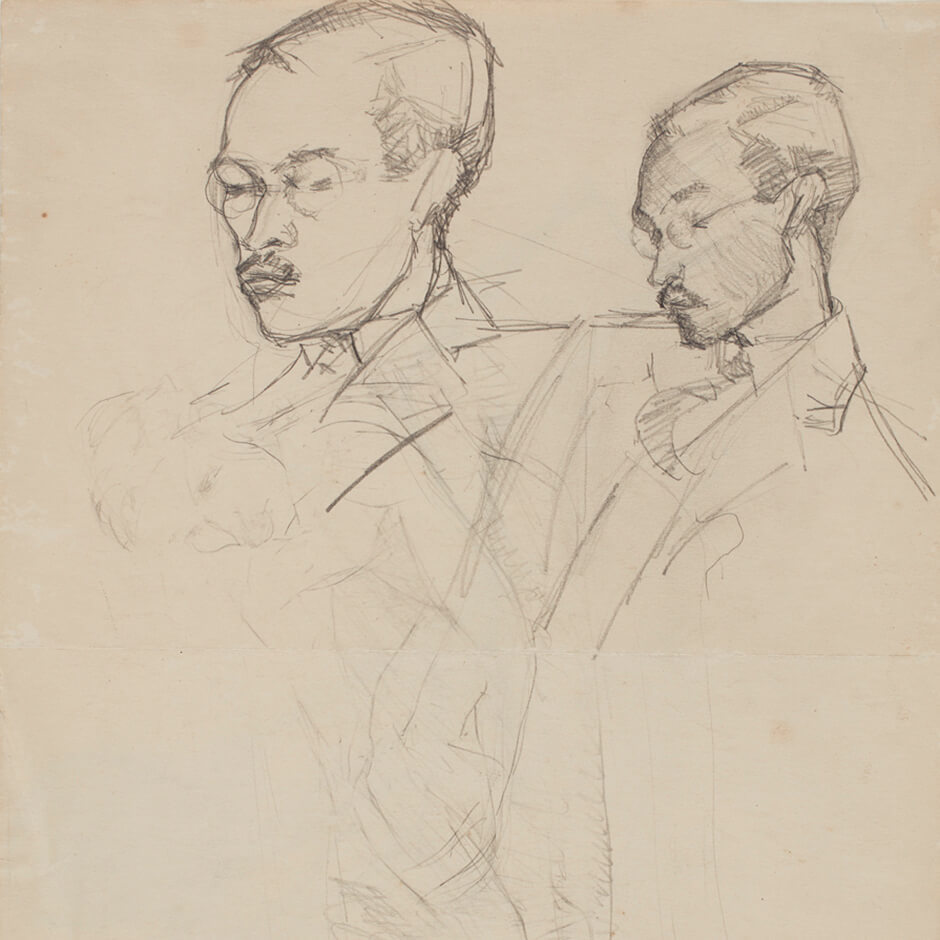

Although Clark’s work at the svoma garnered praise from her teacher, it is unlikely that she and the other students implemented his theories fully during their careers. Still, many of Clark’s paintings show Petrov-Vodkin’s influence. In the Self-Portrait of 1925, the head is built up out of smaller geometric forms, and the two 1933 portraits, Myself and Philip Clark, Esq., demonstrate the way in which she builds form through colour and structural brushwork. Clark’s pencil sketches of her husband from 1933 are sculptural in quality. She also “sculpts” with paint, appearing more confident in her painting than in her drawing.

Just as Petrov-Vodkin would tilt the horizontal and vertical axes (avoiding their static crossing on the picture plane), Clark carries off a tour de force by fitting Philip’s tall frame into a square format and placing him and the chair on a diagonal. The two truly vertical lines in the composition act as stabilizing features—the crease in Philip’s right pant leg, and the edge of the piano behind the chair. The vanishing points fall outside the picture, emphasizing Philip’s height and pushing him out toward the viewer. The result is a more dynamic picture, and one that can be viewed from a variety of angles.

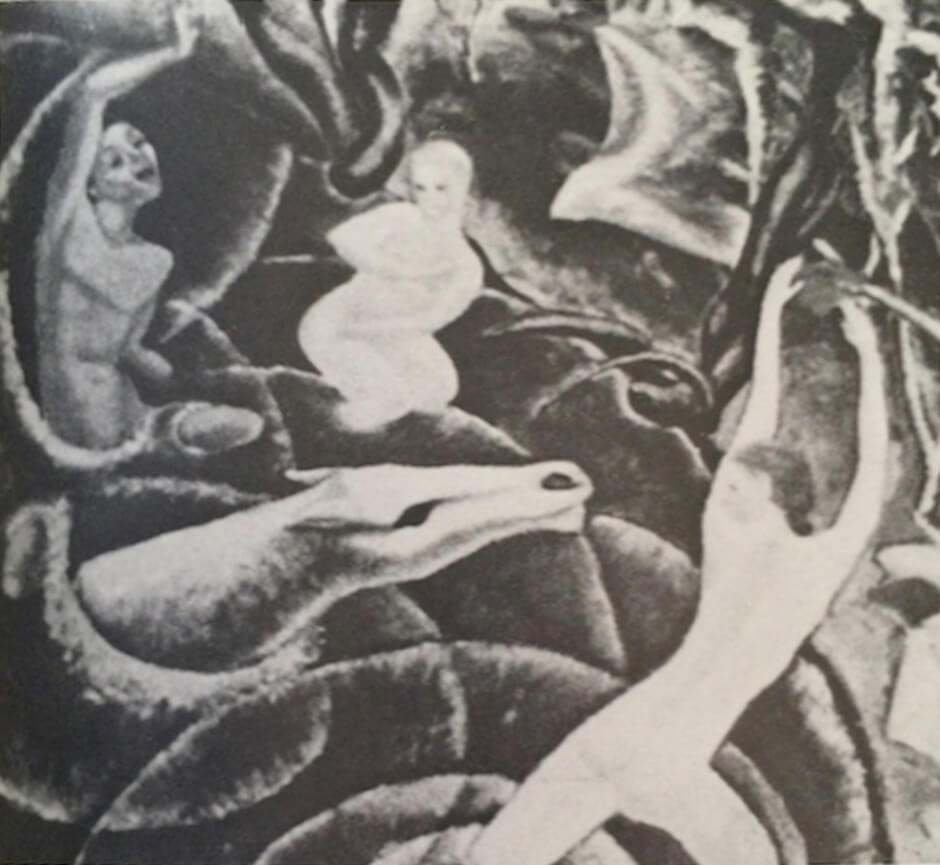

The combination of a high viewpoint and the tilting of horizontal and vertical axes in Russian Bath, 1936, gave Clark a broader pictorial space in which to situate her many figures, but they were too small to provide enough detail, and she did not repeat the composition in later versions. Her still lifes, like Still Life, 1935, however, follow Petrov-Vodkin fairly closely with their slightly elevated viewpoint, avoidance of horizontal and vertical lines, and interplay between forms—reflections in shiny surfaces; the linking of one form with another across space, requiring the viewer to refocus; and multiple viewpoints replicating natural vision. Her still lifes, while similar to those of her Canadian contemporaries, such as Bertram Brooker (1888–1955), have a curious spatial quality that is unmistakably her own. This same quality holds true for her later work, such as Still Life with Alabaster Grapes, 1956. Her entries in the 1937 Canadian Group of Painters show (November–December) amounted to a troika of Russian-inspired work: Petroushka, 1937; Bathing the Horse, 1937; and Wheat Field, 1936.

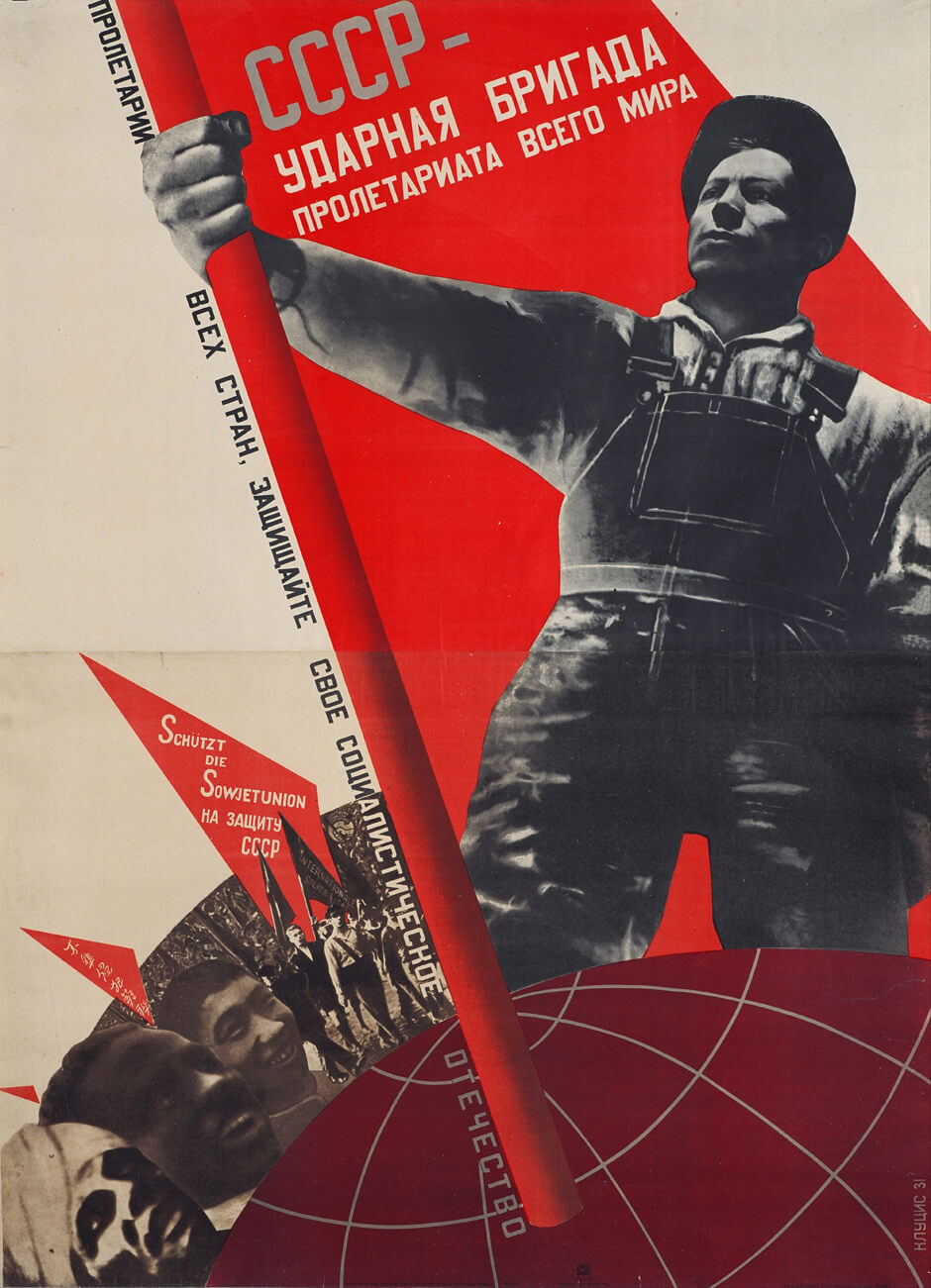

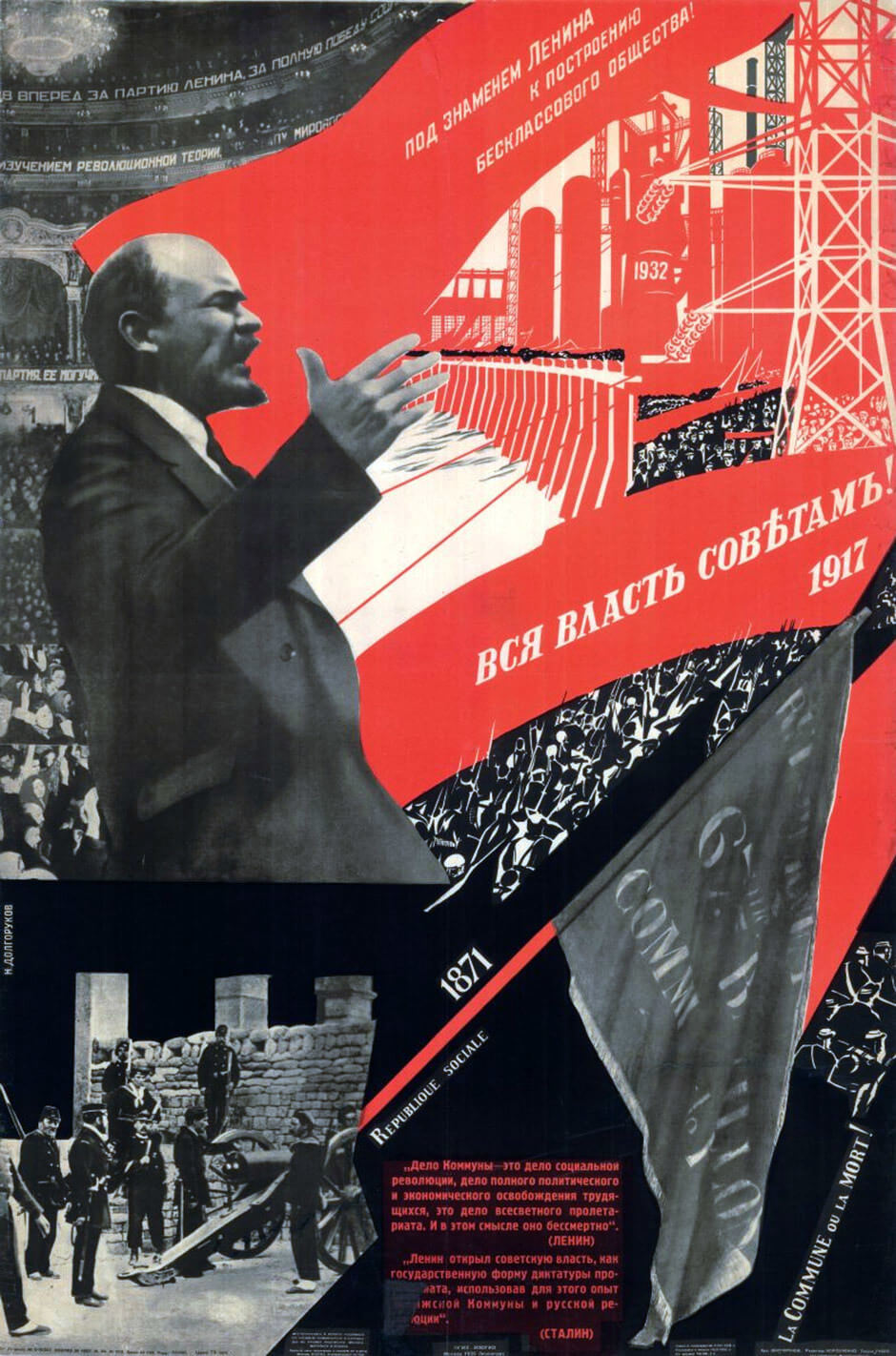

As an art student in Petrograd and in her career up to this point, Clark had not shown any interest in the more radical forms of Russian art (Constructivism). This changed, however, in the latter half of the 1930s. In autumn 1936, Clark ordered specific issues of two Russian art magazines, Iskusstvo (Art) and Tvorchestvo (Creative Work). Iskusstvo 4 (1933) is of particular interest because it contains images of Soviet political posters produced using the technique of photomontage. Some of these posters made using photomontage appear to have inspired the political works Clark produced in 1937 (Presents from Madrid, Petroushka) and 1938 (Mao Tse Tung, Mass Meeting).

Open to innovative ways of creating imagery and in need of a powerful visual language to convey her socialist ideas, Clark adopted some of the avant-garde devices of Russian Constructivism. Such extreme modernism was not acceptable in English Canada, however, and after her friend Graham McInnes called it “propaganda,” she abandoned her experiments with these techniques.

Canadian Influences

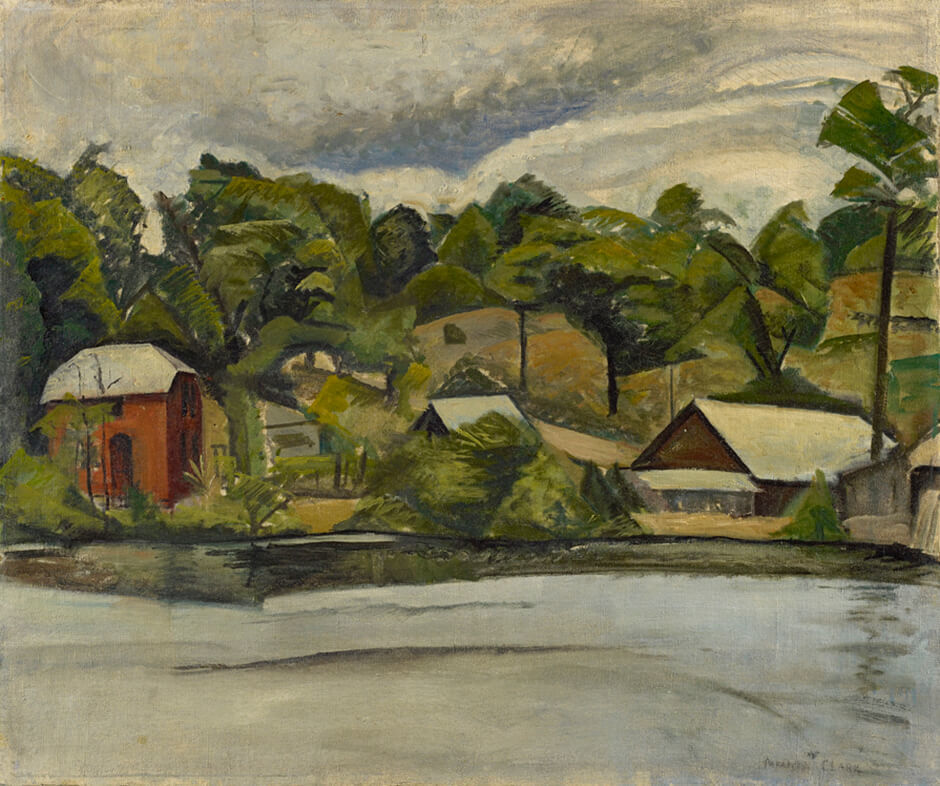

Clark believed that Canada made her an artist—that her creative efforts would have been lost in Paris or Leningrad, where so many artists sought recognition. Once she arrived in Toronto, she had time to work on her art. Her husband, Philip, was very encouraging, as were his friends and other artists she met. Her earliest landscape, Muskoka View, 1932, painted at the Clark cottage, is essentially a Canadian scene interpreted through Cézanne in its planar treatment of landscape features and patches of colour. The inconsistency of technique, however (a thin blue wash fills the foreground), gives the work a tentative quality. Within a few months of her arrival in Canada, she produced a self-portrait (1931–32) and a still life (1931), reminiscent of Petrov-Vodkin, indicating the breadth of her subject matter.

Clark’s paintings from 1933 and 1934 are characterized by a sombre palette and thick application of paint; there is a solidity to the canvases. In 1935, her work lightens up considerably (Still Life, Snowfall) as she introduces large areas of white into the composition. This brightness was undoubtedly the result of painting window display backdrops for René Cera (1895–1992) at Eaton’s, where she made preparatory sketches in watercolour on white paper. Through this connection she met Pegi Nicol (1904–1949), Caven Atkins (1907–2000), and Carl Schaefer (1903–1995), all of whom exhibited with the Canadian Society of Painters in Water Colour. Clark joined them in 1935, showing Overlooking a Garden, 1930.

Through the commercial display work she did for Eaton’s windows, Clark gained the confidence to experiment with different compositions in her oils and watercolours. She became more inventive, bringing together diverse elements from various sources, including her memory, and disregarding consistency in scale and perspective (as in the first version of Russian Bath, painted in 1934, which she gave to Cera).

The Canadian Group of Painters (CGP) became a valuable resource for Clark’s self-education. In 1933 and 1936, she showed with them as an invited contributor, and later in 1936 was elected as a member. From that point on, she was recognized as one of the leading modernist painters in Toronto. Douglas Duncan was also important in developing her career, especially in his role as manager of the Picture Loan Society (founded in November 1936). Clark was thirty-two when she arrived in Canada—not a novice—but she needed to find her place in the local art scene.

After a family vacation in Quebec in the summer of 1938, a shift appears in Clark’s technique. These trips were important for the time they gave her to paint while Philip took care of their sons. She wrote to H.O. McCurry, director of the National Gallery of Canada, reporting that the work she had produced in Quebec had received favourable comments from her friends, and even from “such [a] difficult critic as D. Milne.” The family made several trips to Quebec in the following years. Clark said she respected “all the French Canadians,” feeling a natural affinity with them, and she purchased a watercolour, La Raie Verte by Paul-Émile Borduas (1905–1960), in 1951.

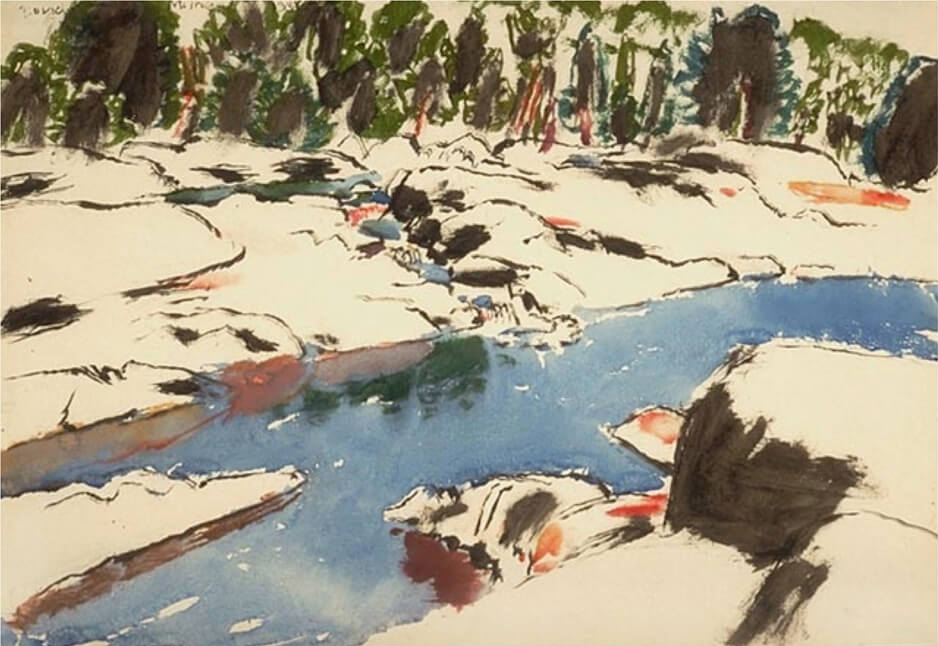

Clark admired David Milne (1881–1953), particularly his watercolours, and several of her paintings from 1938 to 1940 appear to be in response to him. She chose a few of these pieces for the Print Room exhibition she shared with Milne, Schaefer, and Atkins in 1939. Her Landscape with a Lake, 1940, combines elements drawn from her teacher Petrov-Vodkin with Milne’s judicious balance of detail and areas of open ground (The Cross Chute, 1938), but her distinctive palette and attention to foreground detail bear her personal stamp.

Texture, Experimentation, and Abstraction

Soon after Clark attended the Conference of Canadian Artists in Kingston, Ontario, in 1941, and saw some of the demonstrations there, she began to introduce texture to the surface of her paintings. She used varying dilutions of paint (from impasto to washes), dry brush technique, scumbling, and scratching into the wet paint to reveal the support beneath. In October Rose, 1941, the paint is thickly applied, with scratching in areas of the rose petals and the glass, where she has drawn into the wet paint for added definition.

This feature is also present in Clark’s Self-Portrait with Concert Program of 1942. Here, however, the artist has employed different brush techniques to vary the thickness and texture of the paint, applying it more loosely and thinly in the background. This work also contains a collaged element, to make its message more powerful.

Clark preferred to paint directly on canvas, but in the 1940s she began doing oil sketches on site, later enlarging them with the use of grids. Many of these working drawings have survived and demonstrate the care she took in transferring every detail of the sketch onto the gridded paper. She may have used this same technique for the shop-window designs she produced for René Cera, and possibly for the theatre sets she worked on with the Allegri family. Sometimes it was years before she enlarged a work: the final painting, while resembling the smaller version in composition, might have a different support and paint application. But while Noon at Tadoussac, 1958, is slightly looser in treatment, it is faithful to the earlier work of 1944 (Art Gallery of Ontario) on which it is based.

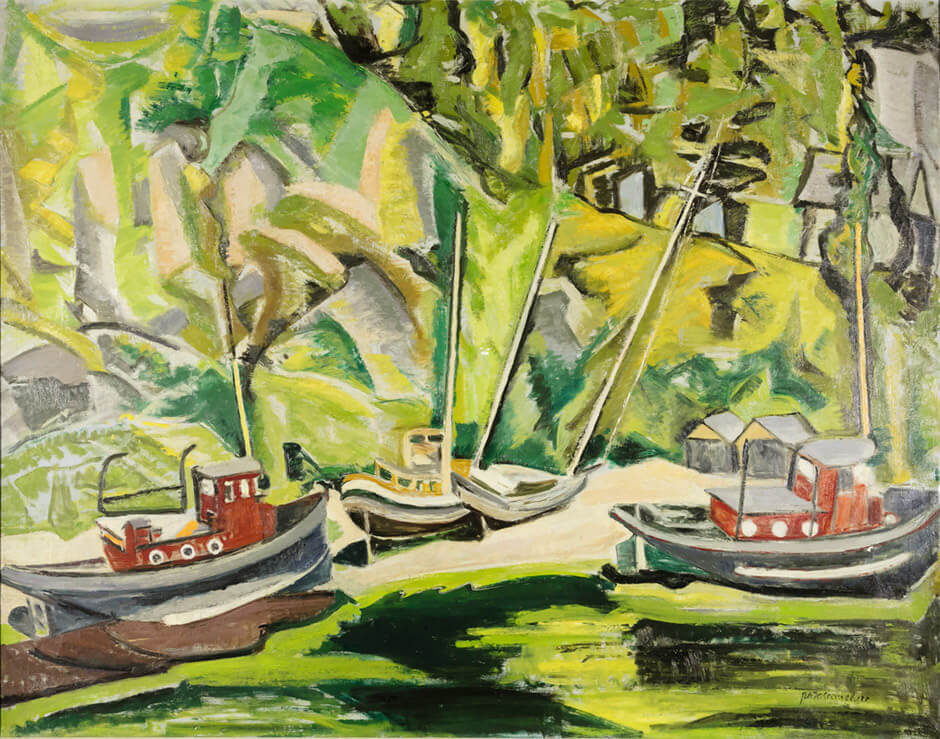

Around 1949–50, Clark began using Masonite as a support. It provides a smooth, rigid surface and could be purchased in large sheets. It was less expensive and time-consuming than stretching canvas and was being used by the younger group of abstract painters. Clark’s first attempts were not entirely successful, but both the sketch (1951) and the larger version of Canoe Lake Woods, 1952, demonstrate her mastery of new materials.

Toward the end of December 1940, Clark became unhappy with her watercolours, which she felt were too heavy and dry. She even considered resigning from the Canadian Society of Painters in Water Colour. By the 1950s, however, she was producing work in both wet and dry techniques that are among her best (November Roses, 1953; Still-life: Plants and Fruit, 1950).

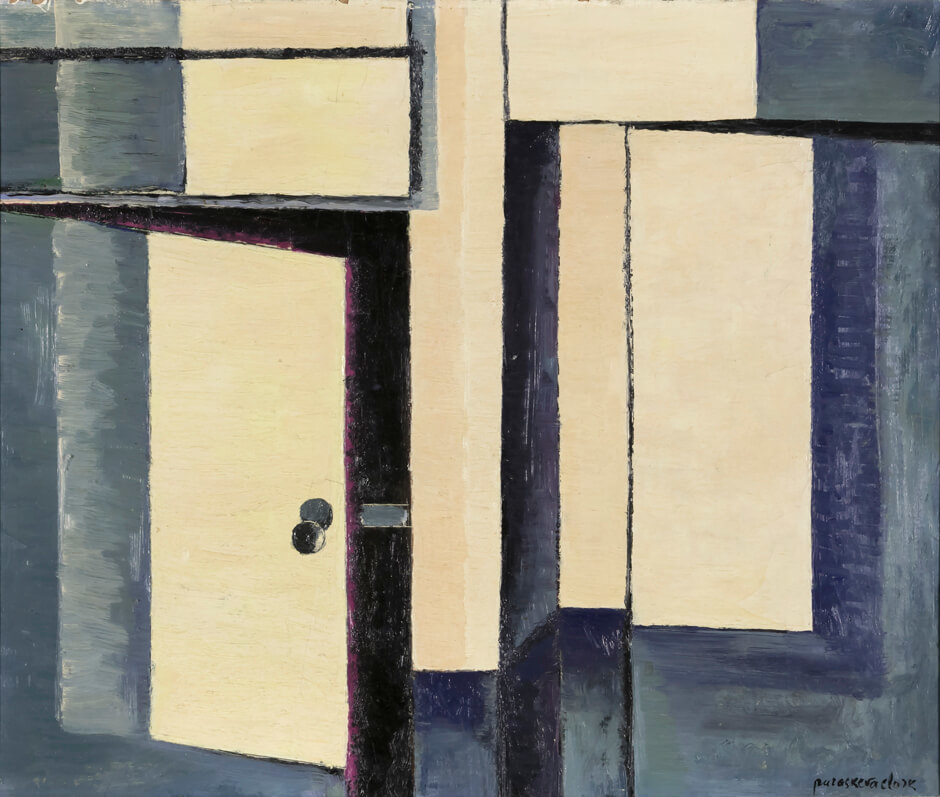

While Clark painted a few abstractions in the 1940s, in response to non-objective work by Edna Taçon (1905–1980) and others she could have seen at Eaton’s Fine Art Galleries, it was not her natural form of expression. In 1956 she offered a “teaser” in the form of Kitchen Cupboard: she presented it in a special section of the annual Ontario Society of Artists exhibition in which visitors were asked to guess the identity of the artists. Clark continued to experiment with a contemporary look by painting on a large scale and loosening her brushwork, as in Sunlight in the Woods, 1966. In the 1960s, she painted the flowers in her garden in various stages of abstraction and attempted to interpret her favourite subjects, including the view from her window, in the visual language of the day—as in Untitled [Mount Pleasant and Roxborough at Night], 1962–63. She tried not to be bypassed by the new art movements and to relate herself to the younger movement. But she remained a realist and a formalist, and it is for that work she is most appreciated today.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements