When Paraskeva Clark (1898–1986), an émigré from Russia via Paris, arrived in Toronto in 1931, the local art scene was ready for a change. The dominant wilderness landscape idiom, rooted in nationalist ideology, was no longer adequate to express the social and political turmoil that would unfold over the next two decades. Clark brought her knowledge of European art and an intuitive socialism to the work she produced in her new home. And while she acknowledged that Canada made her a painter, her art, in turn, offers a key to understanding the diversity of experience that contributed to the visual arts in this country.

Russian Roots

Naturally, fundamentally, I was Russian red without being trained politically. With my soul and my mind, and all the attitude. . . . I was almost twenty-four when I left Leningrad. I just belonged there and I never changed.

—Paraskeva Clark

Born on October 28, 1898, into a working-class family in Saint Petersburg, Paraskeva Avdyevna Plistik was the eldest of the three children of Avdey Plistik and Olga Fedorevna. Because Plistik worked in a shoe factory, the family was provided with the standard accommodation—a one-room apartment in a building nearby. In later years, Paraskeva remembered how the colourful artificial flowers her mother crafted at home to sell for additional income relieved the starkness of this industrial urban environment. When Paraskeva was seventeen, her mother died of pneumonia.

Avdey Plistik, an avid reader of Russian classics he bought second-hand, allowed Paraskeva four more years of schooling than most girls of her socio-economic status received. Plistik’s children would visit their paternal grandparents in the countryside south of Vitebsk in Belarus, nurturing in Paraskeva a lifelong appreciation of nature, open wheat fields, and dense forests. Although her father left the shoe factory to run a small grocery store, Paraskeva secured a clerical position in the same factory when she completed high school, at sixteen. She dreamed of attending drama school and becoming an actor, no doubt enjoying the many forms of theatre performed in pre-revolutionary Saint Petersburg—in factories, fairgrounds, and on the streets. But that career required further education beyond her means, and her creative energies were channelled into the fine arts.

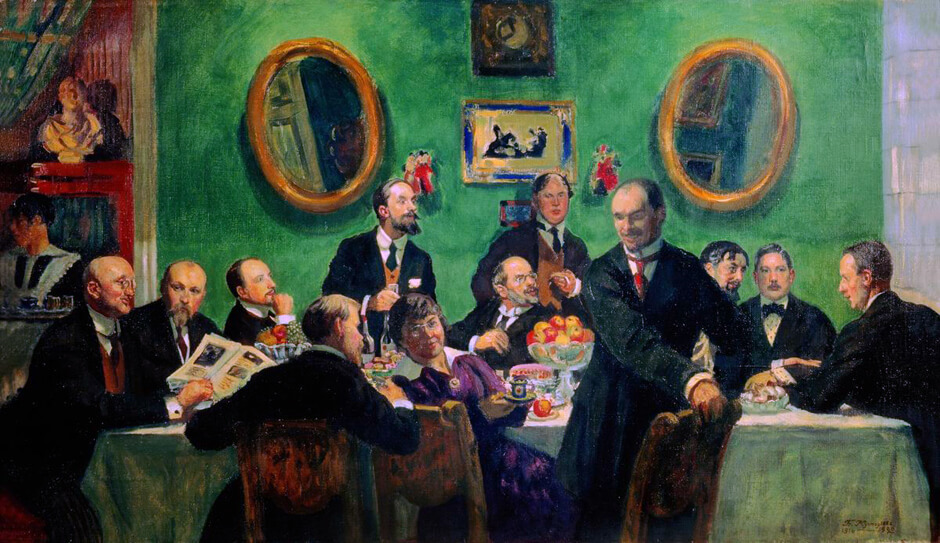

Elza Brahmin, an Estonian co-worker and friend in her mid-twenties, encouraged Paraskeva to enrol in art classes. At the time, Paraskeva was a rebellious, outspoken young woman, unafraid of challenging bourgeois conventions. From 1916 to 1918, she took private evening classes at the Petrograd Academy, drawing plaster heads in charcoal until she acquired sufficient skill to join the advanced students in life drawing. At the academy she participated in lively discussions about Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Cubism, Paul Cézanne (1839–1906), Pablo Picasso (1881–1973), and Georges Braque (1882–1963). The Mir Iskusstva (World of Art) group of artists, led by Sergei Diaghilev (1872–1929), had encouraged East–West cultural exchange through travelling exhibitions in Saint Petersburg and Moscow from 1898 to 1904. As well, after 1909, artists and the artistic intelligentsia in Saint Petersburg had access to the extraordinary art collection of cloth merchant Sergei Shchukin, which included work by Cézanne, Paul Gauguin (1848–1903), Henri Matisse (1869–1954), and Picasso.

Life in Petrograd during and after the First World War and the 1917 revolution was difficult. It was a period of great unrest, uncertainty, conflict, and deprivation for its citizens, who, despite facing shortages of food and fuel for heating, remained optimistic about the future. Paraskeva Plistik continued to work and attend night classes at the academy until it was closed during the summer of 1918, after the Bolshevik regime ordered a complete overhaul of the art-education system. In October, it reopened as one of the Free Art Studios (svomas), and Paraskeva, as a former student, was admitted. For the first year, until she was offered a part-time position in the school office, she continued to work in the shoe factory and attend classes in the evenings. Once she became a full-time student in 1919, she received a small stipend.

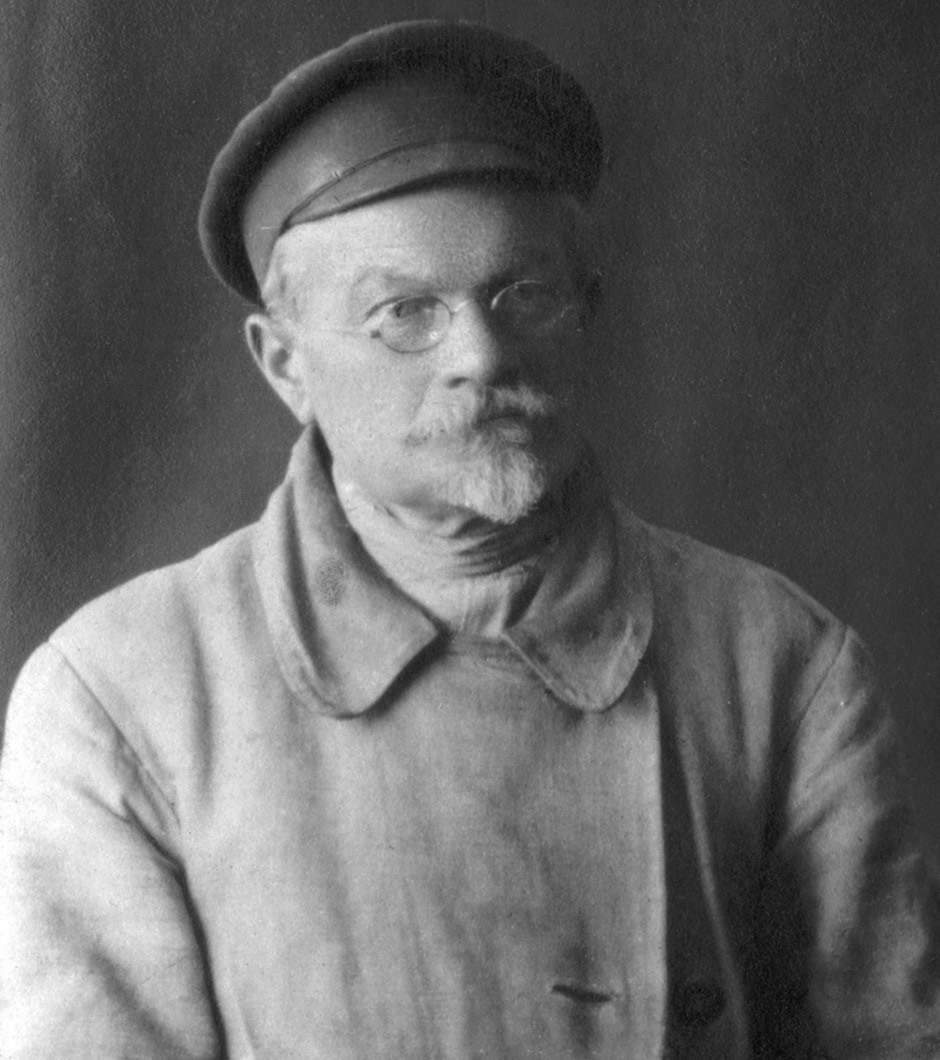

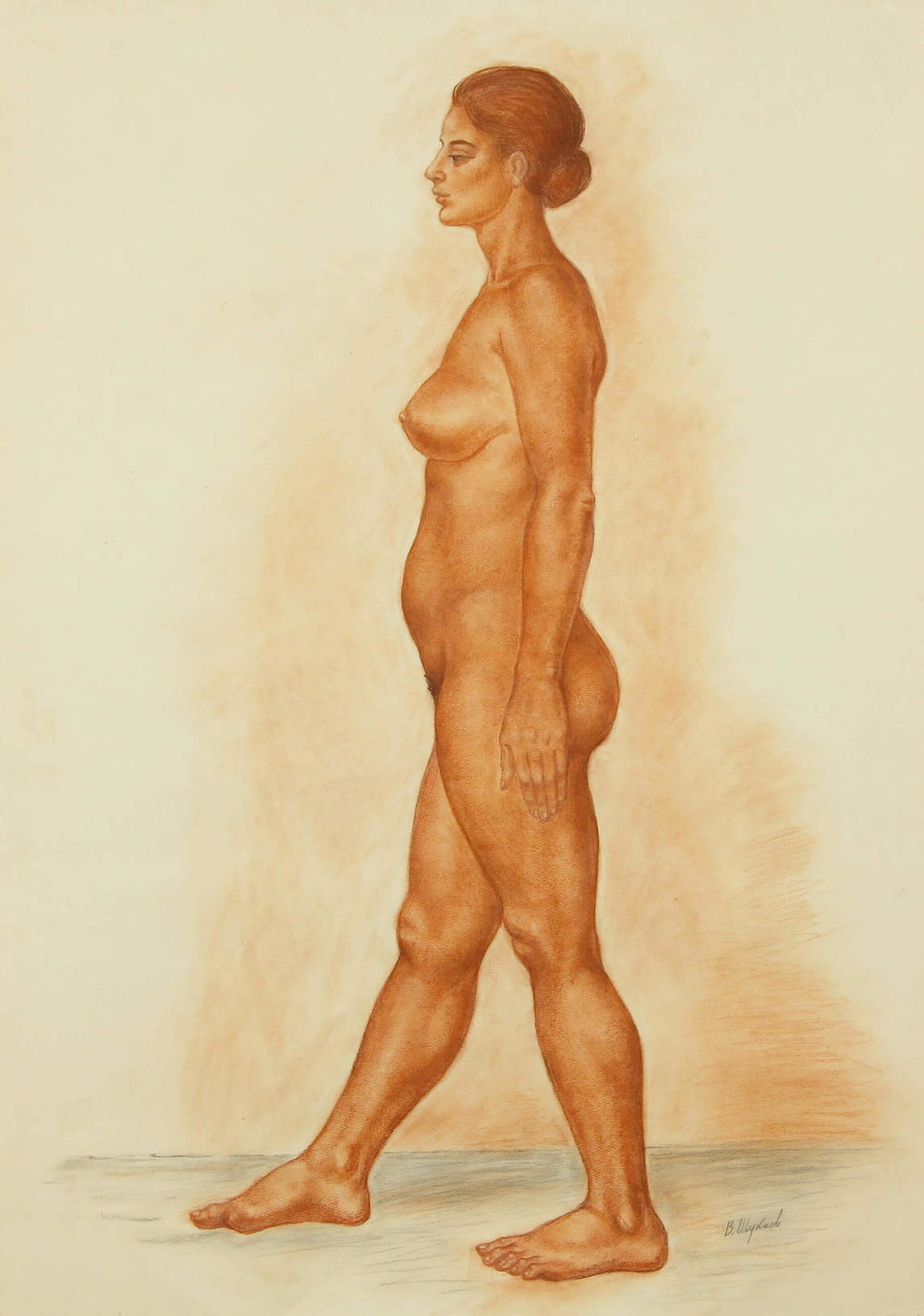

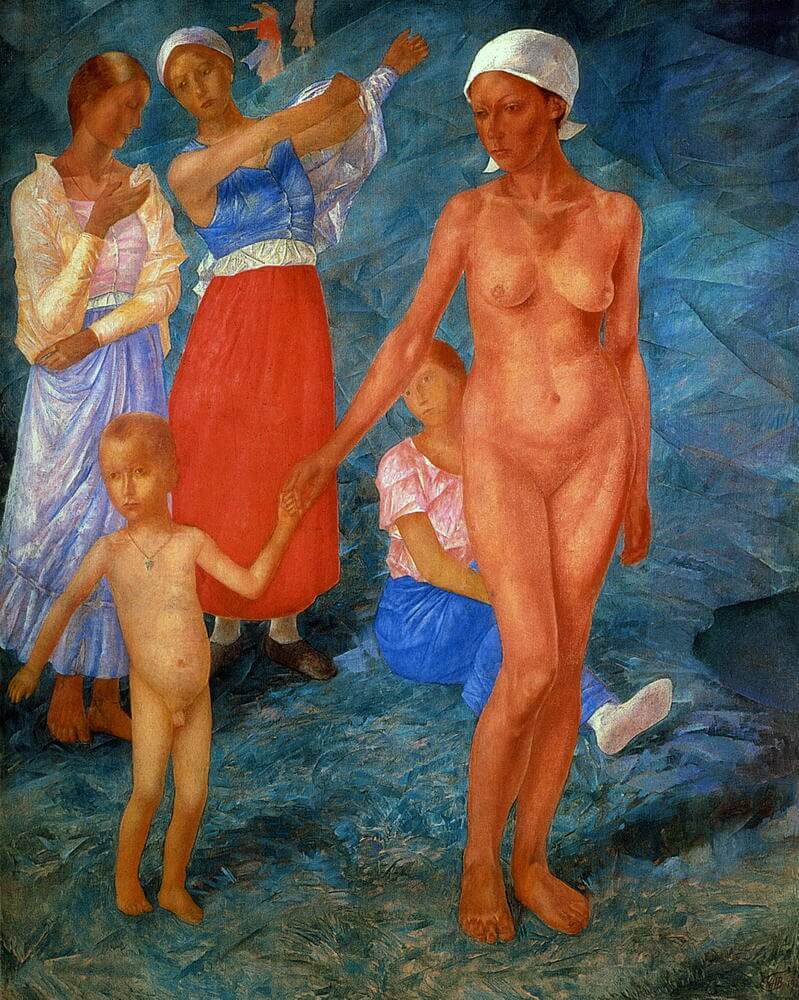

At the svomas, students were able to choose their own instructors. Plistik initially worked under Vasili Shukhaev (1887–1973), whose style she described as “neo-classical.” But she soon became dissatisfied with his teaching methods (week-long poses from the model) and his technique (red chalk drawings and thickly painted oils) and struggled to master figure compositions. When he moved to Paris in the middle of 1920, she joined the class led by Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin (1878–1939).

Petrov-Vodkin had a profound and lasting influence on Plistik’s work. She wrote later that his art “was not like anything I had been used to, not naturalistic nor realistic; it was classic in its simplicity reaching to almost abstraction but with the warm emotion of life within it.” She admitted that it was only in the last five or six months of her “short, irregular and unsystematic” education that she made the greatest strides in her art. By applying what she had learned, rather than relying on intuition, she had won the approval of her teachers and her fellow students by the time she left the school in 1921.

The Theatre and Paris

Also in 1921, the Maly Petrograd State Academic Theatre hired Plistik to paint sets. There she met Oreste Allegri Jr., whose family ran a theatrical design business. His father, Oreste Karlovich Allegri, an expatriate Italian, had been director of stage design for the Imperial Theatres of Saint Petersburg before the October Revolution and had also been affiliated with Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes in Paris since 1909. Around 1920, Allegri Sr. and his Russian wife, Ekaterina Pavlovna Kamenskaya, left Russia and made their home in France, though he continued his business in both countries.

Allegri Jr. and Plistik married in 1922, and their son, Benedict (Ben), was born in March 1923. That same summer, Allegri Jr. accidentally drowned. After some months of uncertainty, the young widow decided to join her in-laws in France, as she and Oreste had planned. Memories of Leningrad in 1923: Mother and Child, 1924, recalls this time—the first painting in a series Clark would return to during difficult periods in her life. In September, she and Ben arrived at the Allegri home in Chatou, an affluent suburb of Paris.

By the 1920s, Paris was home to the largest number of Russian émigrés in Europe, most of them (around 120,000) refugees from the Russian Civil War. Paraskeva Allegri’s life in the city was uneventful; she took care of her child and kept house for her in-laws. Through social events held in the home, however, she did manage to meet painters, actors, dancers, and others connected to the Allegri business and the theatre world. On one occasion she was introduced to Picasso and sat beside him at the theatre, but she had no time for her own art. “In Paris I worked very little by myself, just a few hours, now and then, stolen from housework,” she wrote later. “But my mind, my eyes were painting all the time. My ideas on painting grew in meditations—in seeing occasionally exhibitions of painting[,] particularly [R]ussian artists.” Although Paraskeva Allegri’s later work shows no trace of the more radical Russian art that could be found in Paris in the 1920s, she would have known the work of well-known Russian émigrés living in Paris—such as Mstislav Dobuzhinsky (1875–1957), Vasili Shukhaev, Alexandre Benois (1870–1960), and Zinaida Serebriakova (1884–1967)—that her in-laws were collecting.

In 1929, Paraskeva enrolled Ben in a school where he boarded during the week while she took a job in an interior design store, DIM (Maison de décoration intérieure moderne), in place de la Madeleine, which sold Venini glass and other objets d’art. Photographs show her fashionably dressed in the latest styles. That summer, she met two young visiting Canadians, Philip Clark and Murray Adaskin, when they purchased a small modernist piece of sculpture from her. Philip and Paraskeva became friends and, over the next two years, corresponded in both English and French. In 1931, when Philip (now a chartered accountant) returned to France to visit her, he found her anxious to leave the Allegri home. She was discomforted, she told him, by the unwelcome attentions of Paul Allegri, the younger brother of her late husband. The pair quickly decided to marry in London that June, and at the end of the month, Paraskeva and Philip Clark travelled to Toronto with Ben.

Establishing a Career in Toronto

Paraskeva Clark’s entry into the Toronto art world was facilitated by her husband’s membership in the Arts and Letters Club (he was a talented pianist) and his friendship with the musical Adaskin family. Soon after her arrival, Clark met Lawren Harris (1885–1970), A.Y. Jackson (1882–1974), Bertram Brooker (1888–1955) (to whom she sold a painting in 1934), Elizabeth Wyn Wood (1903–1966), Emanuel Hahn (1881–1957), Charles Comfort (1900–1994), and others.

Hahn suggested that Clark send her Self Portrait, 1931–32, to the annual juried exhibition of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts in November 1932. It was the first time she exhibited anywhere, and it signified, as she put it, “a foot in the door of the temple of Canadian art”—a phrase she inscribed on the back of the picture. Because she felt more comfortable conversing in French than in English during these early years in Toronto, she often went to the Alliance Française. It was probably there that she met the francophile Douglas Duncan, who became a close friend and supporter through his role as manager of the Picture Loan Society, once it was established in 1936.

During her first five years in Toronto, Clark exhibited portraits, landscapes, and still lifes with the major art societies—the Ontario Society of Artists (OSA) and the Canadian Society of Painters in Water Colour (CSPWC)—and contributed to annual exhibitions of the Art Association of Montreal and the Department of Fine Arts at the Canadian National Exhibition. In 1933, when she was invited to exhibit with the newly formed Canadian Group of Painters (CGP), she sent Myself, 1933. It portrayed her pregnant with her second son, Clive, who had been born that summer. Three years later, she was elected a member of the CGP.

Clark had not been impressed by the predominance of landscape painting when she arrived in Canada, but the local art world slowly opened to a variety of forms of artistic expression. Her work fit this broader definition and was included in some international exhibitions: Still Life, 1935, in the Exhibition of Paintings, Drawings, and Sculpture by Artists of the British Empire Overseas—the “Coronation Exhibition”—in London, England, in 1937; and Snowfall, 1935, in the Exhibition of Contemporary Canadian Painting at the Empire Exhibition in Johannesburg in 1937 and its subsequent tour as the “Southern Dominions Exhibition.” Snowfall and Still Life were also among the eleven paintings Clark included in a five-woman show with Rody Kenny Courtice (1891–1973), Isabel McLaughlin (1903–2002), Kathleen Daly (1898–1994), and Yvonne McKague (1898–1996)—all members of CGP—held at the J. Merritt Malloney Galleries in Toronto in January 1936. In March, art critic Graham McInnes wrote favourably about her work, and the following year profiled her in Canadian Forum. Over the next few years, his columns helped her to gain recognition as a progressive artist of note.

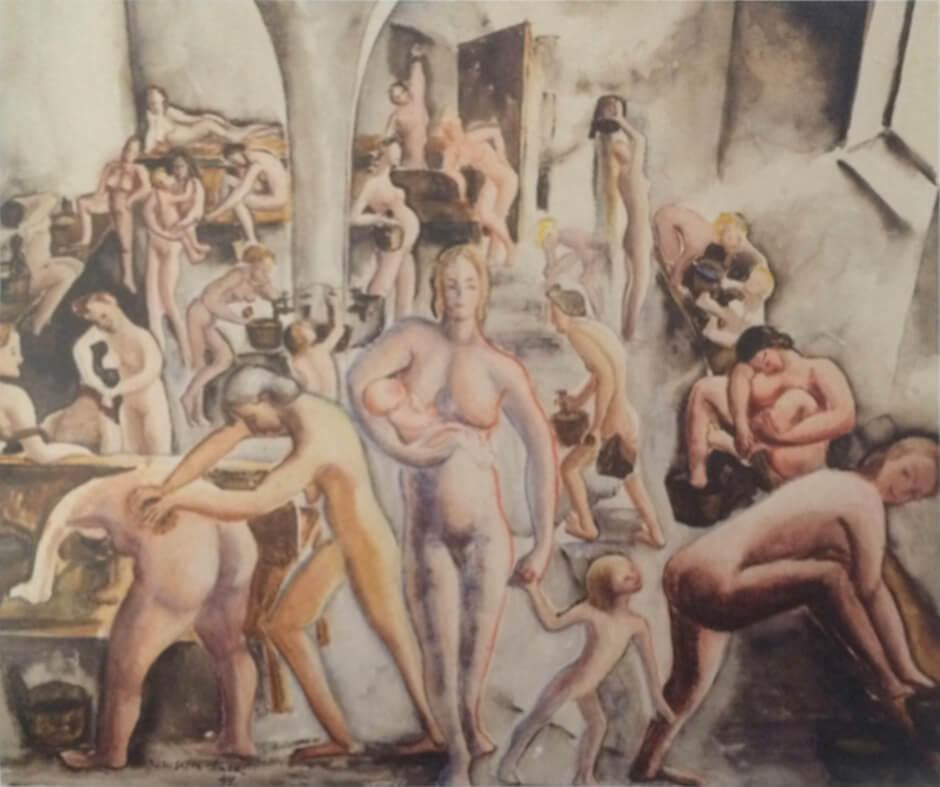

When René Cera (1895–1992), a French architect and designer for Eaton’s department store on College Street, hired Clark in 1933 or ’34 to paint backdrops for window displays, she developed the incentive to push the boundaries of her art practice in new ways. As she worked alongside Pegi Nicol (1904–1949), Carl Schaefer (1903–1995), and Charles Comfort, she attempted more demanding compositions on a larger scale. Several of her sketches for these mini stage sets survive. This experience brought back pleasant memories of painting theatre sets in Leningrad, and during this time she produced her first picture (location unknown) in a second series of Memories of Leningrad, on the theme of the Russian Bath. These pictures reflected periods of happiness in her life—unlike the sorrow-laden Mother and Child series.

Art and Activism

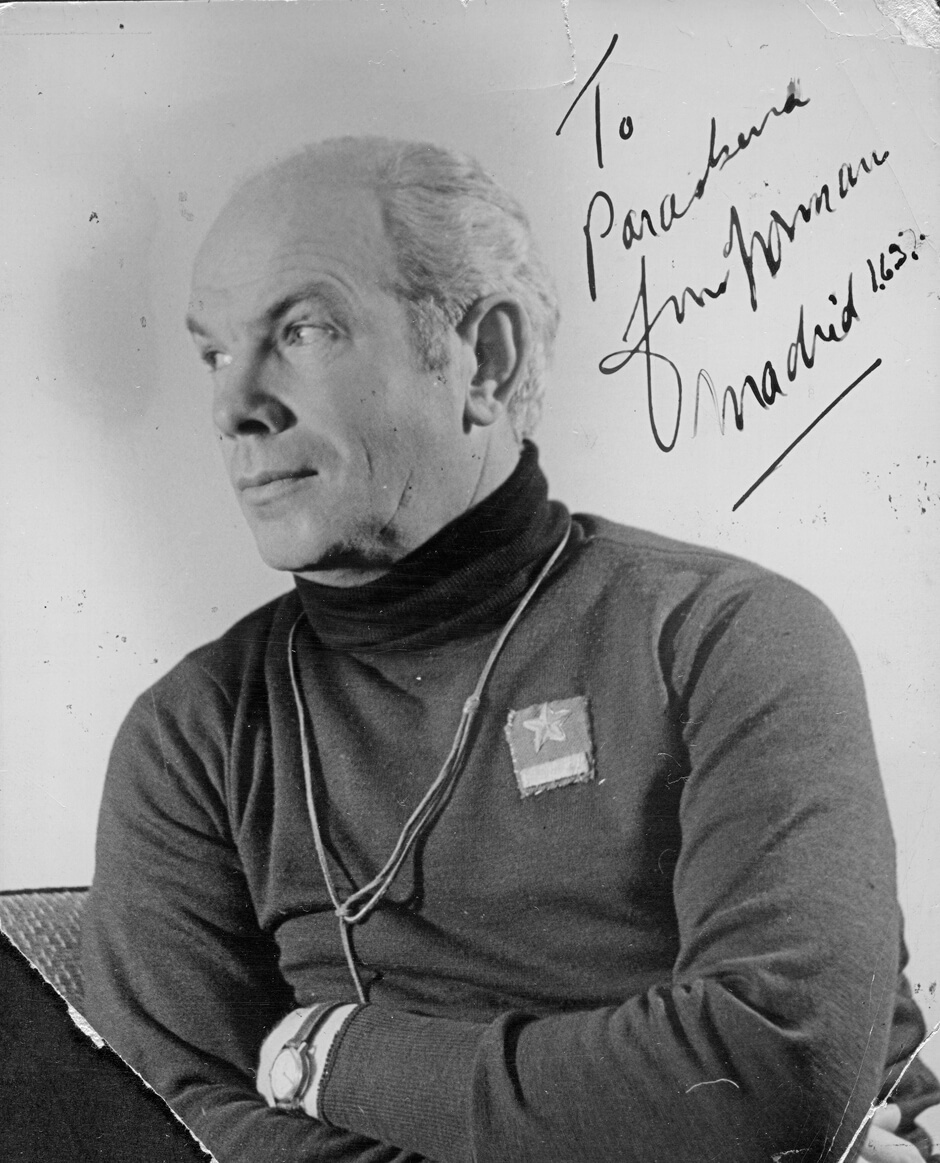

The year 1937 proved to be a significant one in Clark’s artistic development. She was elected a member of the Canadian Society of Painters in Water Colour, the group she exhibited with most often. She was already known for her landscape and still-life paintings, but from this point on she began to address socially relevant subjects in her work, influenced by contemporary events—the Great Depression, the Spanish Civil War—and by Dr. Norman Bethune, whom she had met the previous summer.

Bethune was in Toronto in 1936 to raise money to send medical aid to the Republican army in the Spanish Civil War. He, Fritz Brandtner (1896–1969), and Pegi Nicol crashed a dinner party at the Clarks’ one evening—with profound implications for Paraskeva. Up to that point, she had not been politically minded, but Bethune, who had recently become a Communist and had visited Leningrad the year before, likely encouraged her to become actively involved in the Spanish Republican cause.

As a result of meeting the charismatic Bethune, with whom she had a brief affair, Clark embarked on works based on her memories of Russia—one, a second version of Russian Bath, 1936. She also exhibited her first work with political content, Presents from Madrid, 1937, a watercolour depicting the small mementoes from the war that Bethune sent her in correspondence from Spain. In April, she wrote an article in the left-wing journal New Frontier advocating a role for the artist in society and countering a piece by Elizabeth Wyn Wood, published earlier in Canadian Forum, arguing that artists could ignore social and political affairs.

That same summer, Clark produced her second painting with political content, Petroushka, 1937. She considered this canvas to be her most important work and sent it to the Great Lakes Exhibition (1938–39) and the CGP section of the New York World’s Fair (1939–40), where it would be seen by larger American audiences.

In the closing years of the decade, Clark worked for the Committee to Aid Spanish Democracy and tried (unsuccessfully) to bring Picasso’s Guernica, 1937, to Toronto in 1939 as a fundraising initiative to assist Spanish refugees. She visited New York to see the important Picasso retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in November 1939, in which Guernica was included. J.S. McLean, president of Canada Packers and a collector of Canadian art, financed this trip. He became Clark’s patron in 1938, and in 1940 helped her family to secure a mortgage on 256 Roxborough Street East (now 56 Roxborough Drive), where they moved in 1940.

Clark did not produce a large number of paintings with social purpose during her career, yet they are her best-known works today. In November and December 1939, of the thirteen paintings Clark sent to the Print Room show with Carl Schaefer, Caven Atkins (1907–2000), and David Milne (1881–1953) at the Art Gallery of Toronto (now Art Gallery of Ontario), only two were figure compositions. The rest were portraits, landscapes, and still lifes—all genres she returned to frequently (as with In the Woods, 1939, and October Rose, 1941). In the 1940s, Clark painted a few large figural compositions, including Pavlichenko and Her Comrades at the Toronto City Hall, 1943, and Parachute Riggers, 1947.

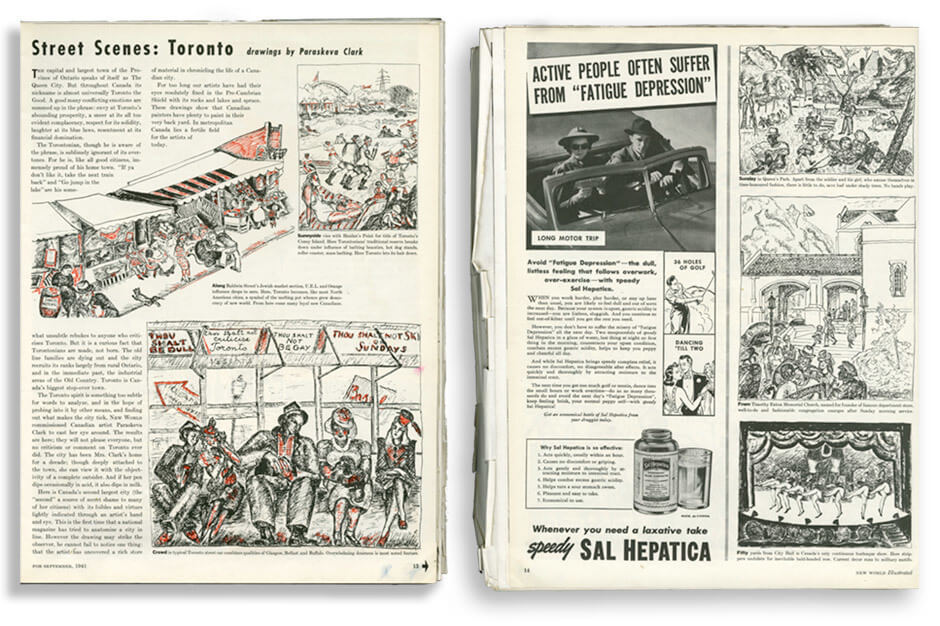

In 1941, Clark contributed a series of pen-and-ink drawings to accompany a text by Graham McInnes, entitled “Street Scenes: Toronto,” for the magazine New World Illustrated. The point of the article was to remind artists that they needn’t travel to the Far North when interesting subject matter could be found “in their own backyards”—the place where Clark often found hers.

Clark attended the Conference of Canadian Artists—a gathering of artists from across Canada who assembled at Queen’s University, Kingston, from June 26 to 29, 1941. Its purpose was to discuss the artist’s relation to society and to demonstrate “technical methods in the light of modern research.” The conference concluded by establishing the Federation of Canadian Artists (FCA), a lobby group to promote the arts and the interests of artists. Clark was a vocal participant during the conference and became a member of the first regional committee of the FCA in Ontario. In the catalogue for the exhibition Aspects of Contemporary Painting in Canada, which opened in September 1942 at the Addison Gallery of American Art in Andover, Massachusetts, she commented on the apathy, shyness, and lack of enthusiasm and fighting spirit among Canadian artists, blaming the Canadian public for showing little interest in art. She advocated artists’ rights in an article in Canadian Art in 1949.

Toward the end of 1941, Clark applied unsuccessfully for a Guggenheim Fellowship to study in New York for one year. Her rough draft reveals her ambition to improve in the area of figure composition (a weakness since her student days) so she could undertake more socially relevant paintings based on the life around her. She explained that she became primarily a landscape painter not only because that genre dominated Canadian art and markets but also because she found figure composition difficult. Later, she told Montreal art critic Lawrence Sabbath that landscape was the easiest painting to do because it didn’t demand the “rigid thinking” required for painting the human figure.

The War and Solidarity with Russia

Clark’s career developed against the backdrop of the Depression and the Second World War. Late in June 1941, German troops advanced into Russia; the siege of Leningrad began in September. While it lasted, until January 1944, Clark had no communication with her family and friends in Leningrad. She never found out that her two siblings had died during the war. Indicating her deep concern for her family abroad and for her homeland, she painted Self-Portrait with Concert Program in 1942.

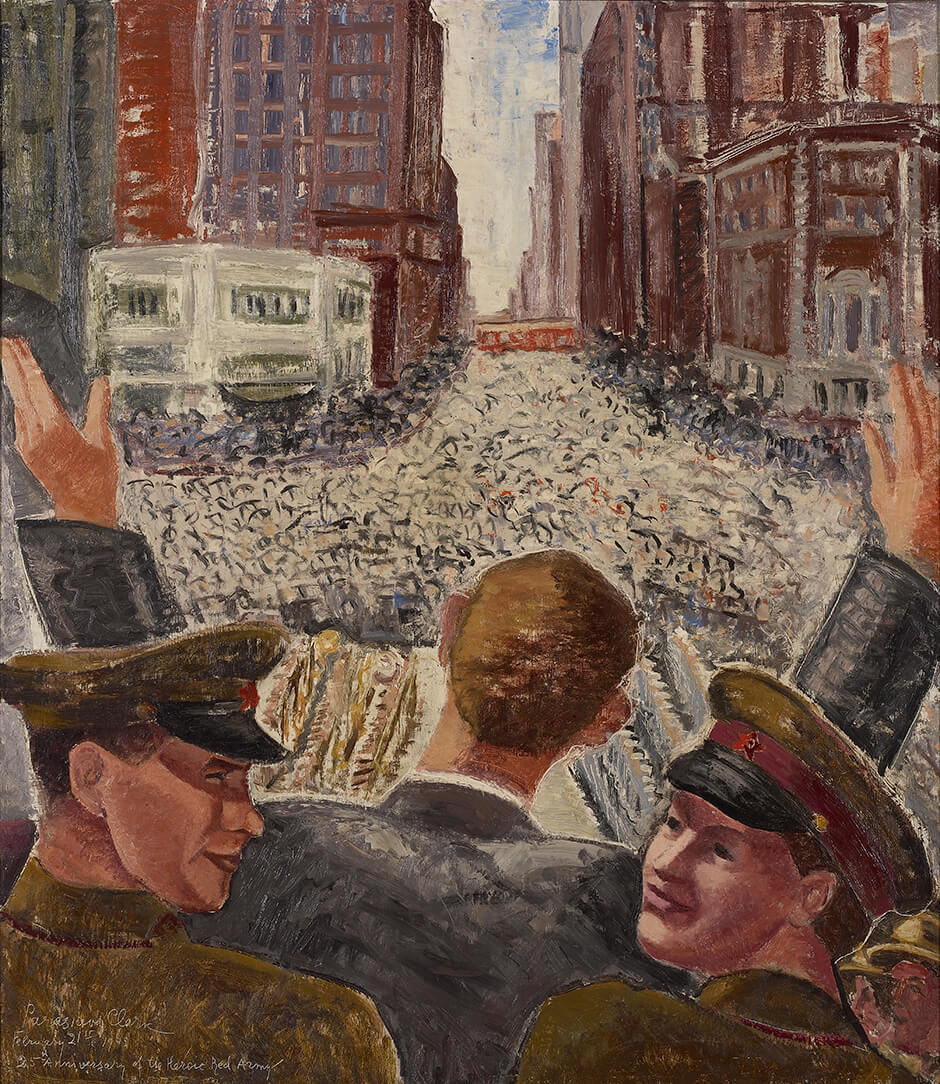

Clark also threw herself into charity work to aid Russia and the war effort. Public sympathy for the Russian cause was running high in Canada. In December 1942, she held an exhibition and sale of her paintings at the Picture Loan Society, her largest yet. With the proceeds, she made a donation of around $500 to the Canadian Aid to Russia Fund, chaired by J.S. McLean. In that same year, she and other committee members welcomed to Toronto a group of young Russian representatives who were touring North America to raise support for their cause. Lieutenant Ludmila Pavlichenko, a celebrated female sniper, was among them, and Clark featured her in a large canvas, Pavlichenko and Her Comrades at the Toronto City Hall, 1943, painted to commemorate the event. She marked the twenty-fifth anniversary of the founding of the Red Army with an inscription in the painting’s lower-left corner, affirming where her sympathies lay.

In November 1943, Clark organized a Russian arts exhibition in conjunction with the congress of the National Council for Canadian-Soviet Friendship. Between 1944 and 1947, until the onset of the Cold War, she prepared and delivered illustrated lectures on the history of Russian painting to a number of groups in Toronto, Montreal, Hamilton, and elsewhere. The promotion of cultural understanding between Canada and Russia became her personal cause. In 1944, she was elected vice-president of the Federation of Russian Canadians and wrote art columns for its newspaper, Vestnik (Herald).

Clark’s painting came to an abrupt halt in April 1943, when her son Ben was hospitalized with schizophrenia. Her prolonged concern and sadness over his illness would seriously affect her productivity as an artist: she looked after him for most of her life, and her travel was limited mainly to family vacations when he could accompany her. Ben was a talented artist but never set out on a life of his own. When Clark began painting again in february 1944, relieved that Ben seemed better and that the siege of Leningrad had finally ended, she produced another version of Memories of Leningrad: The Public Bath.

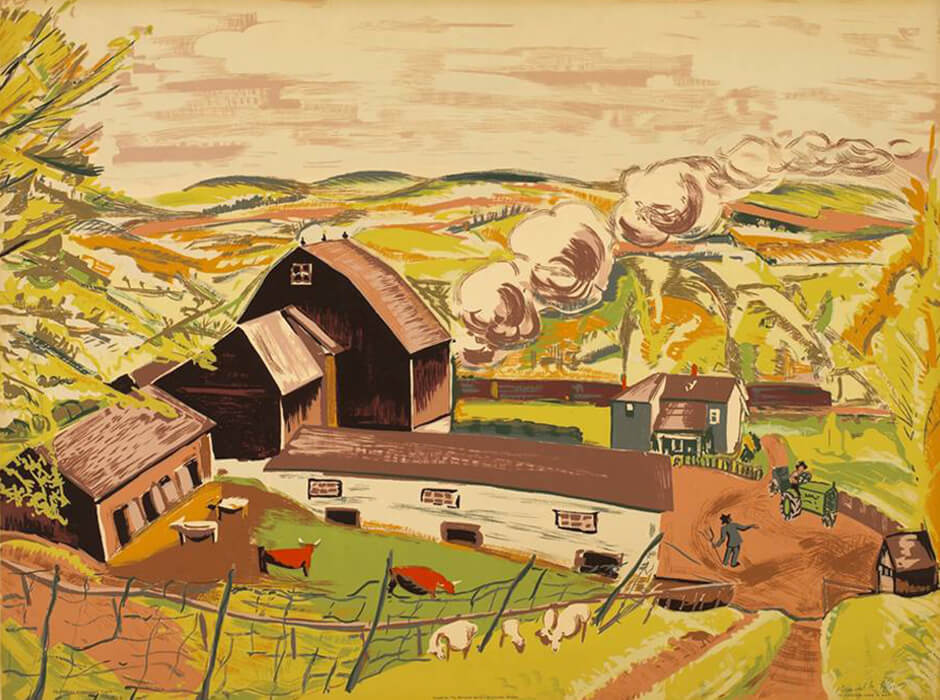

In an article Clark wrote for World Affairs in february 1943, she emphasized the importance of art during wartime. As in her piece for New Frontier six years earlier, she advocated a Canadian art that depicted the human figure in action. In May 1944, she wrote to H.O. McCurry, director of the National Gallery of Canada, registering her disappointment at not having been selected as one of the artists to document war on the home front. In December, the gallery appointed her to depict the work of the Women’s Division of the Royal Canadian Air Force, and Parachute Riggers, 1947, was one of the paintings she submitted. Clark was also involved in the Sampson-Matthews silkscreen project, initiated to provide artwork for the armed services during the war: she contributed the landscape Caledon Farm in May, 1945.

Recognition and Retrospection

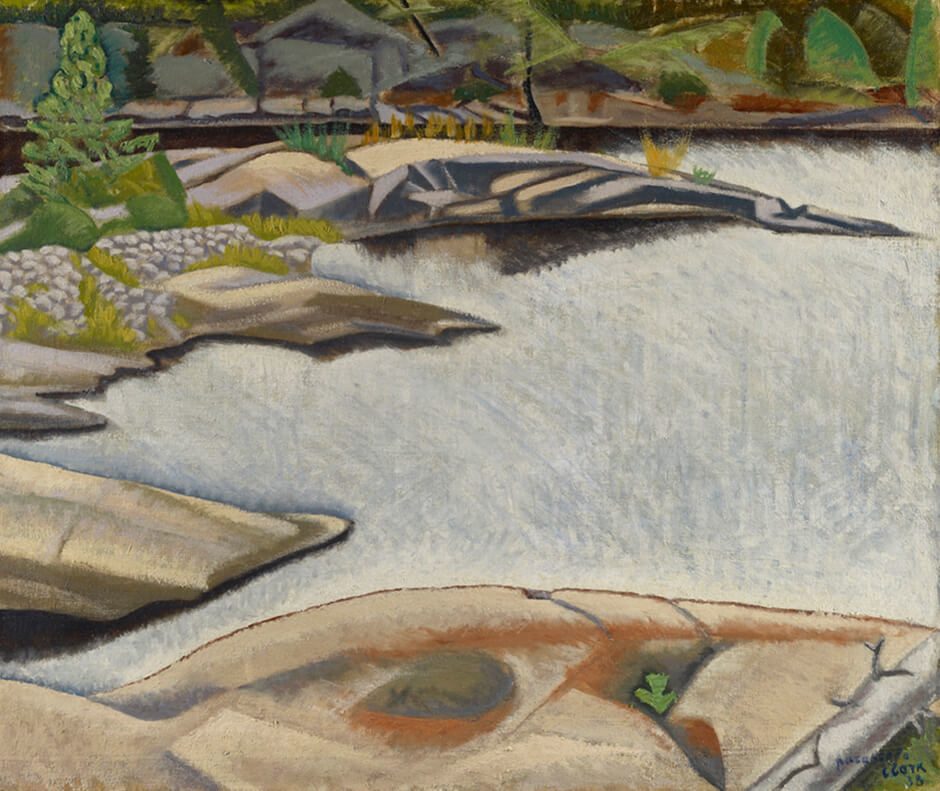

Paraskeva Clark’s artistic output, exhibiting opportunities, and profile increased in the late 1940s. In addition to her domestic and urban surroundings, her summer trips to Quebec, Georgian Bay, Muskoka, and Algonquin Park, and shorter forays to locations north of Toronto, provided ample subject matter for landscape painting—in Canoe Lake Woods, 1952, for example. She held her second solo show at the Picture Loan Society in february 1947, and was elected president of the Canadian Society of Painters in Water Colour in 1948. Her work was exhibited in retrospectives of Canadian art at home and abroad, and Graham McInnes and Donald Buchanan included her in books they published on Canadian art in 1950.

During the 1950s, a number of significant exhibitions of her work included new paintings, though they were largely retrospective in nature, with work borrowed from public and private collections. It was a busy time for her, and she was saddened when her supportive friend J.S. McLean died in September 1954.

Clark’s last solo show as a practising artist was held in the Hart House Art Gallery at the University of Toronto in October 1956, the year she became an associate member of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts. This exhibition contained mostly recent work (1954–56), chosen, perhaps, to appeal to a younger audience; she wanted to appear current. She was delighted when several young members of the new abstract group Painters Eleven attended the opening: receiving recognition from them, she said, made her feel less “useless.” Clark was interested in and supportive of their work, particularly that of Harold Town (1924–1990), although she knew she could not produce their kind of art. She tried, nonetheless—as in Untitled [Mount Pleasant and Roxborough at Night], 1962–63.

Responding to her 1952 exhibition at Victoria College, Carl Schaefer wrote to say how much he had enjoyed her still-life paintings from the 1930s, reminding him of how they had created a period of painting “largely ignored by critics of today” and “smashed by the war.” Clark admitted to Alan Jarvis, the new director of the National Gallery of Canada, that being in the arrière-garde was not a glamorous or heroic role, but a necessary one “for the protection of the life lines of the army.” But she also confided to the Montreal art critic Lawrence Sabbath in 1960 that no artist wants to be bypassed, but “admired, adored and accepted.” She too felt the urge to follow the young movement.

Later Life

In 1957, Paraskeva Clark’s son Ben was hospitalized once again for mental illness. In the years that followed, Clark painted less, spending more time tending the garden, in which she found subjects for her paintings. Clive, her talented younger son, graduated from architecture school and married Mary Patterson, also an architect, in 1959. Their three children became a source of great delight for Clark.

Clark was dealt a further blow in the 1960s when both the Ontario Society of Artists and the Canadian Society of Painters in Water Colour began rejecting her work, leading to her resignation from the OSA in 1965. When she was elected as a full member of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts in 1966, she deposited Sunlight in the Woods, 1966, as her academy piece. Clark stopped showing in art society exhibitions by 1967, finding alternative organizations through which to sell her art.

In 1974, Paraskeva and Ben held a joint exhibition at the Arts and Letters Club, in which she showed a mix of old and new work (Petroushka, 1937, and Myself, 1933, were still in her possession), as well as some of her experiments in abstraction. It was not until the National Gallery’s important 1975 exhibition Canadian Painting in the Thirties, curated by Charles C. Hill, that Paraskeva Clark’s contribution to that decade in Canadian art was recognized. In 1982, curator Mary E. MacLachlan organized Paraskeva Clark: Paintings and Drawings for the Dalhousie Art Gallery, coinciding with the release of Gail Singer’s documentary film Portrait of the Artist as an Old Lady.

Philip Clark died in 1980, and the following year, Paraskeva moved into a nursing home. On August 10, 1986, she died of a stroke in Toronto at the age of eighty-seven.

About the Author

About the Author

More Online Art Books

More Online Art Books

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements